Abstract: While the passage of the 2018 Gender Parity Law was a step in the right direction, progress on women’s political empowerment in Japan has been slow. With a combined effort from advocacy groups, political parties, and the international community to include more women on ballots and support them to electoral success, Japan can move the needle on gender equity in politics.

Keywords: gender, quotas, elections, women’s political empowerment, economic growth

The annual Group of Seven (G7) meeting invites opportunities for multi-national collaboration but also comparison amongst the attending states. The G7 countries (Canada, the United States, United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, France, and Japan, plus attendance from the European Union) indeed share many things in common: they are all relatively wealthy, liberal democracies committed to working together on global issues. Yet the photos from this year’s meeting highlight another questionable commonality: where aren’t there more women in positions of leadership? A deeper look reveals varying levels of gender equality in politics across G7 members with Japan continuing to lag significantly behind.

Image 1.1: G7 leaders gather in Hiroshima in May of 2023. Source: Wikipedia.

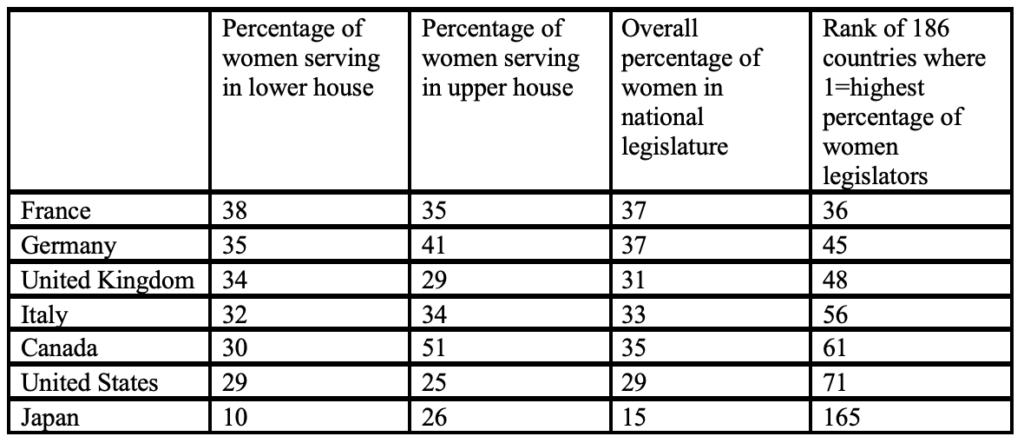

One way to measure gender equality in political leadership is by looking at the share of women in national political positions. The Inter-Parliamentary Union collects data on the percentage of women serving in national legislatures. As the table below demonstrates, among the G7 countries, Japan ranks last, and of the 186 countries where data was collected, Japan ranks 165th.

Table 1.1. Women Serving in G7 National Legislatures as of March 2023 (Inter Parliamentary Union, 2023).

The relatively small number of women candidates in elections offers one explanation for Japan’s lack of women in political leadership roles. Recognizing the problem, the Japanese government announced in 2020 a target of 35 percent female candidates in national elections by 2025. Last year’s upper house election fell slightly short of that goal with a still record-high of 33.2 percent female candidates. Today, a quarter of upper house members are women. Those figures are encouraging, but less impressive when the bigger picture is taken into consideration. The percentage of female candidates in the 2021 general election for the more powerful lower house was just 17.7 percent. Today, the number of women in the lower house is much less significant than the upper house at just 10 percent. The Asahi Shimbun recently reported that in about 40 percent of local assemblies, there is either only one or no female members at all, with women making up only 15.6 percent of all local assembly members (Hayashi and Roppei, 2023).

This gender imbalance in political representation manifests as other inequities throughout the socioeconomic system. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reports the gender wage gap in Japan at 22 percent, well above the 12 percent average for OECD countries. In 2021, women in Japan made up only 13.2 percent of managers compared to the 28 percent OECD average. Women are less likely to serve in any level of government, start a business as an entrepreneur, or work as a civil servant than their male counterparts, according to OECD data. The scarcity of women in politics not only reflects the status of women, but also exacerbates it (Dalton 2021).

One approach to pursuing a more equal balance in national politics is through the introduction of electoral gender quota systems. There are various ways to categorize such quota systems, but the major difference is whether they are adopted voluntarily or are legally enforced. Legal systems mandate quotas through constitutional amendments or other legislation, while voluntary systems leave the responsibility for parity with the political parties. These voluntary systems lack the legal mechanisms for enforcement, such as restrictions on public funding for political parties and campaigns. Of the G7 countries, only Italy and France have mandated legal quotas, though parties in Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom have adopted voluntary quotas. In Taiwan, which adopted gender quotas early in the 1950s and then reformed the quota system after democratization, women made up 42.5 percent of the Legislative Yuan in 2022. This is the highest number in East Asia, where the average was 20 percent in 2020. Of the 12 G20 countries the Freedom House Index rates as “Free,” only 2 (the U.S. and Japan) lack any kind of quota system, whether national or subnational, legal or voluntary. Among democratic countries in the world, gender quota systems are more the rule rather than the exception. Why, then, has Japan yet to adopt a gender quota system to promote more women’s participation in politics?

One answer points to legal barriers. Japan’s 2018 Gender Parity Law, or the Law to Promote Co-participation of Men and Women in Politics, urged political parties to aim at parity in the number of male and female candidates in national and local elections. The law, prepared by an all-partisan working group for women’s empowerment and participation, originally aimed to draft a compulsory quota law, but were constrained by potential constitutional violations. While the Japanese constitution ensures that political parties have the power to recruit and nominate their own candidates, it also prohibits discrimination based on sex. The mainstream view of Japanese legal scholars has been that legally mandated gender quotas would discriminate against men’s’ right to run for office and would therefore be deemed unconstitutional. This isn’t to say that that the adoption of legal quotas would be unconstitutional, just that this is the current and prevailing legal interpretation. When the Tokyo metropolitan chapter of the Liberal Democrat Party (LDP) held a women-only recruitment drive in March of 2023, the branch officers of the Number 18 electoral district (comprised of Musahino, Koganei, and Nishi-Tokyo) sent a letter demanding the all-female recruitment efforts stop. The letter claimed the drive left no room for male candidates and likely violated Article 14 of the constitution guaranteeing equality under the law. There continues to be disagreement within the party as to whether the recruitment efforts aimed at women are desirable or even constitutional. A constitutional amendment to allow gender quotas would also be unlikely given the long and difficult process of constitutional revision, a process that has not been attempted in Japan since the adoption of the 1947 constitution. Consequently, the 2018 law lacks enforcement mechanisms or penalties should parties not nominate male and female candidates in equal numbers.

An additional but related challenge to the adoption of a gender quota system is the perception that they promote unqualified women at the expense of qualified men. One example of this is when, following the announcement of the 2018 law, female LDP member Onoda Kimi tweeted that nominating a “60 percent competent female over a 100 percent competent male” would violate Japan’s national interest (Onoda, 2018). Onoda also claimed in the same Twitter thread that it wasn’t harder for women to run for office, but that fewer women wanted to do it in the first place.

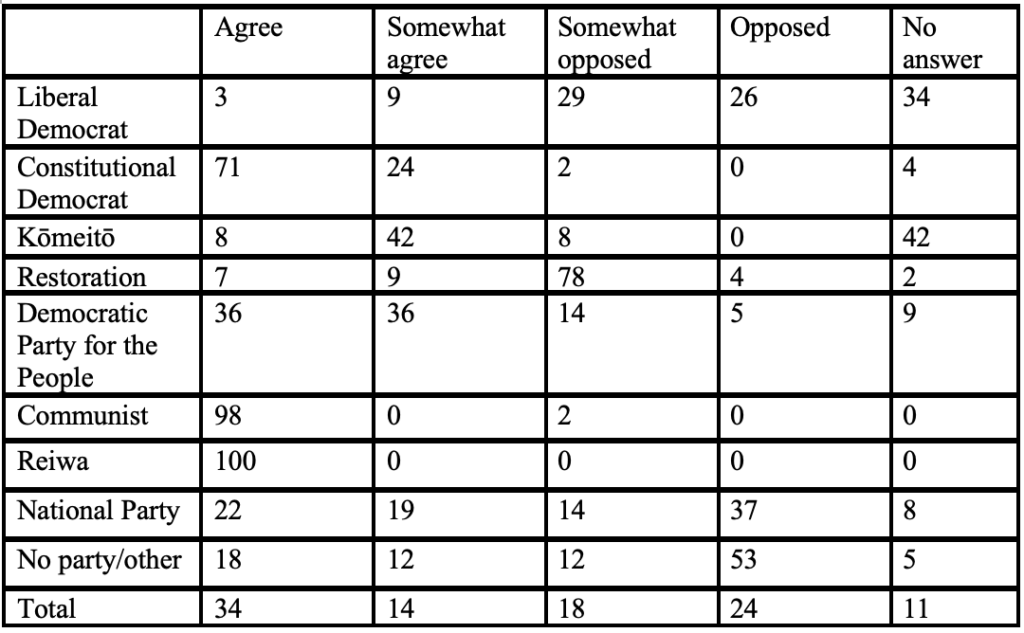

We should not assume Onoda’s reasoning is representative of the entire LDP. However, a recent NHK poll does reveal a comparative lack of enthusiasm within the party for implementing gender quotas. The table below shows percentages of 2022 upper house candidates’ responses to an NHK poll when asked whether they “support the introduction of a quota system that allocates a certain percentage of candidates and seats to women” (translations are the author’s). 29 percent of LDP respondents reported being “somewhat opposed” to the introduction of a gender quota system and 26 percent of respondents were “opposed,” while 34 percent chose not to answer this question.1

*517 respondents (94.9%) as of the date of publication (June 2022)

Table 1.2: Partisan Tally, 2022.

The more likely explanation for the LDP’s lack of support for the adoption of a voluntary gender quota system is that it would require the LDP to give up many of its incumbent seats in the Diet. For progressive opposition parties, quotas offer a chance to promote their vision of gender equality. By holding fewer seats, the opposition parties also have fewer male incumbents on their candidate lists each year. Instead, these parties are able to field new candidates, many of which can be women. The LDP, however, is predominantly male, with 92 percent being incumbents in the lower house and 85 percent incumbents in the upper house (Miura, McElwain, and Kaneko, 2022). Since party endorsement is usually guaranteed to incumbents, adopting a gender quota system would displace some of these male incumbents, or at least require a change in the endorsement process.

But in at least one respect, Onoda is correct—it can be more difficult to recruit women to run for office in Japan. This is unsurprising, given the documented history of abuse women candidates have faced. In 2014, Suzuki Akihiro (LDP), member of the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly, publicly apologized to fellow assembly member Shiomura Ayaka (Your Party) after shouting sexist remarks during her speech about increased public support for pregnant women. Suzuki shouted “You should get married!” as Shiomura spoke at the Tokyo Assembly. Other women candidates have reported inappropriate touching, insults, interruptions, heckling, and comments about the inappropriateness of mothers running for office, both from voters and from other candidates or lawmakers (Khalil, 2023). In 2021, the Gender Parity Law was revised to include a clause that bans gender discrimination and sexual harassment in elections, though the inclusion of a quota requirement was dropped from the amendment because of opposition from the LDP and the far-right opposition Japan Innovation Party (Nippon Ishin no Kai). The amendment requires central and local governments to provide support for women to pursue a political career while balancing family responsibilities and to offer programs that increase awareness about the problem of harassment while providing counseling for women running for office. Though the amendment recognizes an important barrier to women’s political empowerment, a lack of consequences for ignoring the legislation complicates whether it will have much of an impact in the future.

If legal or constitutional gender quotas are unlikely for the time being, then we might ask under what conditions would voluntary quotas in Japan be able to increase the number of women candidates in elections? Below, I identify and discuss strategies to promote the implementation of voluntary gender quotas that could move Japan toward greater gender parity in elections.

It seems clear that the LDP must be willing be adopt and seriously pursue a gender quota system in order for the number of women on candidate lists to increase. Studies show that, when implemented without loopholes that allow merely symbolic compliance, gender quotas can increase women’s participation within even one election cycle.2 Research also shows that voluntary quotas are especially effective when adopted by a single party that dominates the political system, such as the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa (Somani, 2013, 1481). Though I have already discussed why the LDP’s adoption and serious implementation of quotas might seem unlikely, there are a few actions that could increase the chances of this happening.

The LDP did adopt a gender parity target of 30 percent women candidates in the 2022 upper house election, but only met that target with the last-minute addition of women candidates to the bottom of Proportional Representation (PR) lists. In the end, female candidates only made up about 20 percent of successful candidates from the LDP. Greater preparation and intentionality from within the party would put more pressure on the LDP to comply with their own targets. This recommendation is complicated by the fact there seems to be some disagreement within the LDP as to what actions to recruit women are appropriate and nondiscriminatory. An additional complication concerns the structure of the Japanese electoral system itself. The parallel voting system, introduced in the 1994 electoral reform, allows dual candidacy on a Single-Member District (SMD) ballot and a Proportional Representation (PR) list. That means if a candidate does not win their SMD race, they can be added to a PR list and still gain a seat on the party ticket. In the past, this system has benefitted incumbents (mostly older males) who lost their SMD races. I wouldn’t be the first to suggest that reserving seats at the top of these lists for female or minority candidates would greatly increase these candidates’ chances of success in elections.3 In the 2005 general election, Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro supported a significant number of women candidates to run as “assassins” against incumbents who opposed his post-privatization reforms. Of the 33 hand-picked nominations, 11 (or one-third) were women, forming a de-facto gender-based quota for that election. Even an informal seat-reservation system can increase the number of women on ballots without calling constitutionality into question. In a promising development, the LDP officially set a target for 30 percent female candidates in all elections within the next ten years, including a measure to allocate top spots on PR lists to women.

In recent years, there has been increasing pressure from domestic women’s groups to include more women candidates on ballot lists. Groups pushing specifically for gender quotas in elections have been around since the early 1990s in Japan. One of the current groups lobbying for more women in decision-making roles is Kuotase o suishin suru kai (Q no Kai), a collective of about 60 women’s groups that began working together in 2012. In addition to holding webinars and workshops for women who are interested in running for office, Q no Kai also lobbies legislators directly and holds meetings in the Parliament building. In fact, their lobbying efforts were key to the passage of the 2018 Gender Parity Law. Focusing Q no Kai’s and other groups’ efforts on building pipeline programs to political leadership could lessen concerns within the LDP about inappropriate recruitment efforts, and more women would be prepared and available to be added to candidate lists. This may also address a concerning pattern of candidate shortage that has been tied to general population decline, leading to about 40 percent of seats running uncontested in the April unified local elections (Kitado 2023). These kinds of recruitment and training programs have had success in the past; the Academy for Gender Parity, modeled after the U.S. program Ready to Run, had 28 participants in its first program in 2017. Of those, 7 have run for office and 4 have won seats (Enzmann, 2019). The more these training programs can prepare women candidates to run for office, the easier it is for all parties—including the LDP—to recruit potential women candidates.

Pressure from outside the party could also force the LDP’s hand in quota compliance. The LDP’s alliance partner, Komeito, a party long associated with the religious group Sokka Gokkai (SG), is considered more progressive on sociocultural issues than the LDP. This is demonstrated in Table 1.2 by relatively high numbers of support for gender quotas. The party’s election manifestos from 2017–2021 were dominated by policies geared toward Sokka Gokkai’s Women’s Division, including more affordable education, a commitment to child support, increased support for elder and family care, and other family subsidies (Klein and McLaughlin, 2023, 72). Komeito has also recently supported controversial separate surname legislation. This is at least partly because the SG’s Women’s Division has been one of Japan’s most effective vote-gathering groups and because the party caters to the interests of its constituents (Ibid, 2023, 71). To a significant degree, this also makes the LDP dependent upon support from Komeito supporters, an estimated 20,000 votes in each Single Member District race (Ibid, 2023, 80). Though a junior alliance partner, Komeito has demonstrated significant power in influencing the LDP and actualizing policies that benefit its core constituency in past years. If Komeito encouraged the LDP on the issue of voluntary gender quotas, perhaps by tying the issue to positive economic outcomes, the LDP may be swayed to pursue ballot equality more seriously. This strategy may be complicated by Komeito’s recent losses in the April 2023 unified local elections, likely a result of voter hesitancy about the party’s ties to a religious group in light of connections between politicians and the Unification Church in the wake of Abe Shinzo’s assassination. However, it is yet unclear whether this pattern will hold in national elections.

Japan is also a signatory to treaties that add international pressure to address its shortage of women in political office. For example, in 2010, the United Nations’ Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) charged Japan to undertake affirmative action to increase women’s participation at all levels of decision-making, including in politics, business, and bureaucracy. However, the UN can’t be the only international actor to pressure Japan. The G7 meetings are an ideal time to share strategies among members for increasing women’s political participation. France only introduced a de facto quota system into law to promote gender parity in politics in 1999, when it was looking to take on a more significant leadership role in Europe, as Japan is doing in East Asia. The G7 meetings, however, tend to prioritize discussion of cooperation on economic and national security issues. In doing so, world leaders fail to recognize the many studies that causally link women’s equality with better economic performance and enhanced national security.4

Pressure to support and adhere to voluntary gender quotas from not only within its own party, but also from without by its coalition partner, nongovernmental advocacy groups, and the international community would be difficult for the LDP to ignore. But there is also a carrot that can be used in addition to the soft stick of applying pressure to the LDP. The “Womenomics” initiative was largely successful at instituting policies that encouraged more women to enter the workforce. The end goal of these policies was not necessarily gender equality, but rather economic growth, a long-time key focus of the LDP’s campaign platform. A large body of research supports the idea that women’s participation in politics can be similarly linked to economic growth by encouraging technological innovation,5 increasing the quality of governance and transparency,6 and by influencing policy adoption that favors labor force productivity.7 The general consensus is that women’s empowerment is an important driver of economic growth at the regional and national levels,8 and there is an increasingly large body of evidence to suggest that this includes political empowerment. In Japan’s case, linking women’s political empowerment to economic outcomes satisfies the LDP’s need for an economy-focused campaign message while also promoting gender equity in a similar fashion to the Womenomics initiative and labor force participation.

The passage of the Gender Parity Law was a step in the right direction and, while progress on women’s political empowerment has been slow, it has also been consistent. Two Japanese opposition parties, the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) and the Japan Communist Party (JCP), had candidate lists with at least 50 percent women in the 2022 upper house election. Even better, women accounted for more than half of all successful candidates from these two parties, demonstrating the parties’ genuine efforts to promote female candidates. The 2023 unified local elections also demonstrate progress toward greater gender equality. In Ebetsu, a small city in northern Hokkaido, more than 40 percent of city council members elected were women, many nominated from the Japan Communist Party and from Komeito. A record seven women were elected mayors outside of ordinance-designated cities, bringing the total up to 6 female mayors out of 23 wards in Tokyo alone. Overall, 21 percent of candidates were female and a record 316 women won seats in the 2023 local elections, compared to 237 women in the 2019 election. But this number is still only 14 percent of all available seats. Though there were some big wins for women LDP candidates in the local elections, like Arfiya Eri in Kitakyushu and Konno Momoko in Saitama, the Japan Innovation Party (Ishin no Kai) gained ground outside of their home base of Osaka. In the past, Ishin has expressed strong opposition to gender quotas.

Despite progress, there are many remaining challenges to achieving gender equality in Japanese politics. With a combined effort from advocacy groups, all political parties, and the international community to include more women on ballots and support them to electoral success, Japan can move the needle on gender equality in politics.

References:

Dalton, E. (2021). Sexual Harassment in Japanese Politics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Enzmann, J. (2019). “Setting the Stage for Greater Gender Parity in Politics.” Sasakawa Peace Foundation, 8 October. https://www.spf.org/en/spfnews/information/20191008.html

Hayashi, M. and Roppei T. (2023). “Survey: Women members make up only 15% of all local assemblies.” Aashi Shimbun, 18 February. https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14842725

Inter-Parliamentary Union. “Monthly Ranking of Women in National Parliaments.” IPU.org. https://data.ipu.org/women-ranking?month=1&year=2023

Khalil, S. (2023). “The female mayor in Tokyo fighting Japan’s sexist attitudes.” BBC News, 7 March. https://www.bcc.com/news/world-asia-64874853

Kitado, A. (2023). “Japan has a candidate shortage for local elections on Sunday.” Nikkei Asia, 8 April. https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Japan-has-a-candidate-shortage-for-local-elections-on-Sunday

Klein, A. and McLaughlin, L. (2021). “Komeito in 2021: Strategizing between the LDP and Sōka Gokkai,” in Japan Decides. Pekkanen, R., Reed, S., Smith, D., eds. Palgrave Macmillan, 71–85.

Miura, M., McElwain, K. M., and Kaneko, T. (2022). “Explaining Public Support for Gender Quotas: Sexism, Representational Quality, and State Intervention in Japan.” Politics and Gender 19(3): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X22000617

Onoda, K. [@onoda_kimi]. (2018). あと、仮に候補者選定の時に政治家として100点の資質をもつ男性と、60点の女性が候補だったとして… [also, at the time of candidate selection, suppose a man with 100 points and a woman with 60 points are candidates…]. (Tweet). Twitter.com, 16 May. https://twitter.com/onoda_kimi/status/996756196936663040

党派別集 [“Partisan Tally”]. (2022). NHK.com, June. https://www.nhk.or.jp/senkyo/database/sangiin/survey/touhabetsu.html

Somani, A. A. (2013). “The Use of Gender Quotas in America: Are Voluntary Party Quotas the Way to Go?” William and Mary Law Review 54(4): 1450–1488.

Wikipedia. “Leaders at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, 19 May 2023.” (Photograph). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/49th_G7_summit#

Notes:

Onoda responded to this question with “somewhat opposed” in 2022.

See Drude Dahlerup, Women in Arab Parliaments: Can Gender Quotas Contribute to Democratization?, AL-RAIDA, Summer/Fall 2009, at 28, 32. Miki Caul Kittilson, In Support of Gender Quotas: Setting New Standards, Bringing Visible Gains, 1 POL. & GENDER 638, 639-40 (2005). Novi Rusnarty Usu, Affirmative Action in Indonesia: The Gender Quota System in the 2004 and 2009 Elections, ASIAONLINE, Mar. 2010, at 9-10, available at http://www.flinders.edu.au/sabs/asianstudies-files/asiaonline/AsiaOnline-01.pdf.

See Shin Ki-Young in “Would gender quotas for lawmakers work in Japan?” (2023). Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/03/08/national/social-issues/gender-equality-politics-quotas/

See Valerie Hudson’s Sex and World Peace (2012).

See Dahlum, S., Knutsen, C., and Mechkova, V. (2022). “Women’s Political Empowerment and Economic Growth.” World Development, 156. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.105822.

See: Dollar, D., Fisman, R., and Gatti, R. (2001). Are women really the “fairer” sex? Corruption and women in government. J. Econ. Behav. Organiz. 46, 423–429. DOI: 10.1016/S0167-2681(01)00169-X.

See: Wängnerud, L., and Sundell, A. (2012). Do politics matter? Women in Swedish local elected assemblies 1970–2010 and gender equality in outcomes. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 4, 97–120. DOI: 10.1017/S1755773911000087.

See: Mirziyoyeva, Z. and Salahodjaev, R. (2023). “Does representation of women in parliament promote economic growth? Considering Evidence from Europe and Asia.” Frontiers in Political Science, 5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1120287.