Abstract: This article develops a case study of two settlements of Japanese colonists—one ethnically Japanese, and one Okinawan—in the southern region of the Canadian province of Alberta between the 1910s and 1930s. It explores these communities’ aims and institutional structures to propose that these shaped membership in the trans-Pacific imperial Japanese imaginary, one that—in the navigation of dual Japanese and British Dominion imperial loyalties—sought to promote Japanese racial progress and cultivate the Japanese identity of future generations. It adds to scholarship on imperial Japan’s projection into North America through it’s diaspora. Highlighting southern Alberta’s Japanese communities, a distinctive opportunity is opened to view communities that sat beyond the frontier edges of Japan’s imperial projection and explore the traces of the imperial Japanese imaginary that animated it.

Keywords: Nikkei; Japanese diaspora; Japanese Canadian; Okinawan; Buddhism; Alberta, Canada; Japanese Empire

In the great plains that roll east of the Rocky Mountains, in an area stretching from the Canada-United States border northwards to Calgary, waves of Japanese migration have shaped this region’s life and land. In the mid-twentieth century, for example, inflamed by white “politics of racism” (Sunahara 1981), the Canadian Government’s systematic wartime removal, dispersal, and dispossession of some ninety-five percent of its own citizens of Japanese descent resulted in the area becoming Canada’s third largest centre of Japanese Canadians. Understandably, the “Evacuation”—as this forced uprooting is euphemistically known—dominates Canadian academic, activist, and popular historical production on Japanese Canadians.

Yet, there is another, earlier story of Japanese migration into this area, that of the senjūsha (original settlers). Like the wartime displacement of Japanese Canadians into southern Alberta, the story of the senjūsha reveals how individuals and the communities they grew negotiated competing interests, loyalties, and identities of both the Japanese and British imperial imaginaries they inhabited. On the one hand, they joined the Canadian nation-state building project, arriving at a time when the province of Alberta had only just been established to extend into the North American prairies the full political sovereignty of Canada, which was itself a Dominion territory of the British Empire. As this article will argue, however, they did so in ways that, instead of jettisoning their Japanese identity in order to integrate into the mainstream society of their new home as some have argued, they called upon, adapted, and deployed ideals, values, and institutions they brought from Japan. Becoming Canadian for them was in part an opportunity to affirm and assert being Japanese. Crucially, this assertion was far from accidental. Rather, it was a long-sighted initiative framed in terms of aims to advance Japanese racial progress, cultivate the Japanese identity of future generations, and construct institutional forms that self-affirmed their membership of an imperial Japanese imaginary.

Illustrative in its treatment rather than chronological and narrative, this article highlights moments between the 1910s and 1930s, a period when Japanese migrants became settlers and their settlements evolved into long-standing communities. It focuses on two settler groups: one, ethnically Japanese, scattered around the agricultural town of Raymond, and another, ethnically Okinawan, located in the coal-mining hamlet of Hardieville. As an investigative case study of a little-known story in the Japanese diaspora, this article suggests how the history of imperial Japan and its diaspora intersected with that of the British world in an area usually unassociated with the Japanese empire, the Canadian prairie.

In fact, evidence that reveals the Japanese presence in southern Alberta is scattered and scarce, not least because so much of it was actively expunged. In anticipation of the outbreak of trans-Pacific hostilities in 1941, for example, southern Alberta’s Japanese Buddhist leadership undertook a series of actions to deflect white suspicion and accusations of anti-Canadian sedition like the “complete removal” of anything “redolent of Japanese-ness” including the goshin’ei (the Emperor’s portrait; Reimondo Bukkyōkai, 1970, 40). Nevertheless, traces are still detectable across an array of sources. Central are the writings of the community’s issei (‘first generation’) leaders: the privately published memoirs of Reverend Kawamura Yūtetsu (1908-2005; Kawamura 1988) whose Jōdo Shinshū ministry was foundationally galvanizing in the 1930s; a personal history of the Okinawa Dōshikai (‘Compatriots Association’) penned by one of its 1921 founding members, Higa Shūchō (1904-1993; Higa 2011; Interview: Urasaki 2011); and the official institutional history of the Raymond Buddhist Church (Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970). Then, there are the echoes of memory from oral history interviews that reveal the importance of Japanese cultural and social resources. There are excerpts from my interview engagements with over forty nisei (‘second generation’) collected between 2011 and 2017 (see, Aoki 2020, Aoki, 2019), as well as extracts from Calgary’s Glenbow Museum oral history collections (Sunahara, 1977). Autobiographical family portraits narrating personal histories of origins and journeys on the one hand (LDJCA History Book Committee, 2001; Okinawan Cultural Society, 2000), complement quantitative data compiled in official records on the other: the Canadian census; Imperial Japanese Statistical Yearbooks; and surveillance records of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (1941-1949). Local English-language newspapers, the Japanese-language expat press, as well as the Kanada dōhō hattenshi(History of the Progress of Japanese Compatriots in Canada; Nakayama, 1918) compiled by the Japanese Consulate in Vancouver provide contrasting insights.

Southern Alberta’s Japanese Canadians in the first half of the twentieth century as a focus of scholarly historical study remains largely untouched with the exception of two relatively obscure essays. The first is David Iwaasa’s (1978) account of the community in which he was raised. While well observed, this chronological narrative uncritically assumes a zero-sum assimilationist teleology in which Japanese-ness—at most a temporary stage—gives way to full Canadian identity. Historical contingencies, hybridizing cultural forces, and competing discourses and affiliations that might shape racial identities, ethnic culture, ideological commitments, and individual as well as community aspirations, are problematically ignored. The second by Fujioka Toshihiko (2010), writing some thirty-five years later, avoids an easy Japanese-contra-Canadian binary relationship, not least because he highlights local intra-Japanese divisions and attempts to overcome them in the 1930s emergence of the Buddhist church. Although the extension of institutional Buddhism into southern Alberta might suggest how trans-Pacific diasporic identity navigated both local and global contexts in the wider juxtaposition of Japanese and British imperial imaginaries, this is never explicitly addressed. Of course, the influences that shape social and cultural identity are varied and complex: push-pull pressures for parents and children arising as a result of participation in Albertan mainstream education; military service in both imperial Japanese and British empire wars; navigating industrial relationships through labor union membership; competing models of gender for women—all of these will be touched on to illustrate the complexity of evolving Japanese-Canadian identities. Throughout this article, however, the spotlight given to how southern Alberta’s Japanese settlers drew upon, adapted, and deployed social and cultural resources from their homeland often in deliberate if ad hoc ways, offers a corrective to the simplistic reading, as Iwaasa asserts, that in “[deciding] that their future now lay in the land of their adoption—southern Alberta,” the Japanese made a “simple transfer of allegiance to King and country from Emperor and empire” (Iwaasa 1978, 21-22, 27-28). As this article will argue, Japanese identity as framed by self-asserted membership in an imperial Japanese imaginary stubbornly persisted to evolve in meaningful and purposeful ways.

Conceptualizing ‘imperial Japanese imaginary’

It is this complex ambiguity—an attempt to explore how migrations across the Pacific fostered trans-national identities and affiliations—that has animated much recent research. Sidney Xu Lu’s (2019) work, for example, argues that “migration-driven expansion” in the early twentieth century was a phenomenon that “[transcends] the geographical and temporal boundaries of the Japanese empire” (8). This conceptual framing of the projection of Japanese population and authority beyond the territories of the formal empire is germane to southern Alberta, though to be certain, Lu’s pivotal focus on the diverse agendas of “Malthusian expansionists”—policymakers, business elites and owners, intellectuals, bureaucrats, and others (5)—tends to amplify the motivations and arguments of those within Japan in order to evolve their settler colonial projects. Less audible is the experience of the actual settlers. This is a concern which Eiichiro Azuma (2019) addresses in his exploration of the ishokumin, a “peculiar expansionist concept and practice” that conflates the “acts of ‘migrating’ overseas (imin) for temporary work and of ‘colonizing overseas territories’ (shokumin) as settlers” (5). Going beyond a simplistic conceptual understanding of Japanese colonization outside the formal empire, ishokumin is a historical process that narrates the trajectories of individual migrants’ lives together with the wider ideologically over-determined if “elusive” notion of kaigai hatten (‘overseas development’). Like Lu, Azuma seeks to identify a distinctive Japanese form of “adaptive settler colonialism” across Japan’s “imperial Pacific” (4–9). In fact, as this article argues, the southern Alberta situation doesn’t go this far: evidence is insufficient to argue that its Japanese communities sought the “usurpation of land and other fundamental modes of production…from local ‘native’ residents’ and construct a ‘new Japan’ or ‘second Japan’” (6) that would extend an imperial Japanese political, bureaucratic, security, economic, and/or social presence and authority. Yet, Azuma’s focus on the “intimacies and interchanges” as well as the “diverse experiences” and the “contrasting subject positions” that might help us understand the perspectives of individuals coming from the formal Japanese empire (9–10) is compelling because it privileges the voices of the settlers themselves.

This is where the idea of an ‘imperial Japanese imaginary’ is germane. Drawing off of Benedict Anderson’s re-definition of the nation as imagined, “because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion (6)”

recent scholarship has evolved the concept of ‘imagining’ to explore trans-national ‘imagined communities’, and crucially for us, the imagined sense of belonging they generate. Christina Klein (2003), in her reworking of Edward Said’s Orientalism to explore the re-invention of Asia in Cold War American perception, deploys “global imaginary,’

an ideological creation that maps the world conceptually and defines primary relations among peoples, nations, and regions [,] an imaginative, discursive construct…[and an] abstract entity of the ‘world’ as a coherent, comprehensible whole [that] situates individual nations within that larger framework. It produces peoples, nations, and cultures not as isolated entities but as interconnected with one another (emphasis mine; 23].

I cite Klein’s definition at length because it illustrates how “communion” can involve imbricated layers of identification and affiliation: national and political, social and cultural, racial and ethnic, and spatially across entire spans of the globe like Klein’s trans-Pacific America. To this might be added empire, as Kate McDonald (2017) does in her study of Japanese imperial nationalism and tourism, or sort of. In her reading, a social imaginary of the nation promoted “geographies of solidarity” (42) through the “territorializing” practice of tourist travel across colonized lands (49). McDonald doesn’t go so far as to develop the idea of imperial imaginary. Nevertheless, she cues how identities and affiliations of—a sense of belonging to—the imperial metropolitan center vis-à-vis the empire might be produced, enacted, embodied, transported, transplanted, and strategically deployed by imperial subjects on the move as tourists and colonists within the formal empire, and for us, as migrants in the Japanese diaspora beyond the empire’s boundaries.

Southern Alberta’s Japanese inhabited a region far beyond the peripheries of even Japan’s informal imperial enclaves along North America’s west coast. In this light, the idea of imaginary is particularly salient. In the aspirations and perspectives of these settlers, framed by their past lives in imperial Japan, they actively and expressly asserted their membership of an imperial Japanese imaginary whose racial-ethnic identities and cultural values could be projected into the unlikely territory of the North American hinterlands. They strategically, if cautiously, adapted as Toake Endoh (2009) observes of Japanese informal colonial activity in Latin America, “their ‘home’ state’s vision of reproducing a perfect Japan in the Americas” (6). In this sense, it is germane to understand southern Alberta’s settlers’ efforts in terms of Endoh’s argument more generally of Japanese population movements through Hawai’i to the North American west coast, that “a diaspora’s political or symbolic resources may also be a major attraction to the expansionist home state;…[its] presence or wealth in a foreign country helps the home state raise its prestige in international relations” (Endoh 2009, 8-9). It is for this reason that semi-autonomous associations like the Vancouver-based Nihonjinkai (‘Japanese [Residents’] Society’) and official Japanese representatives like the Vancouver Consulate kept tabs on Japanese settler communities in Alberta, for instance, the visit of the Consul-General in 1920 and reports like Nakayama Jinshirō’s (1918, 43–58) survey of Japanese Canadian community development. In turn, when southern Alberta’s settlers required assistance, they reached out to these west coast organizations (Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970, 18). Nevertheless, the kind of “ethnic community” which Masumi Izumi (2020, 60–61) describes of the extensively integrated and networked cultural and social infrastructures characterizing larger west coast population centers was beyond either the resource capacities or reach of southern Alberta’s dispersed and isolated Japanese. Their belonging to an imperial Japanese imaginary was all the more imagined and perhaps in turn more powerful because self-assertion and local initiative was sometimes the only proof of membership.

Indeed, at least until the 1930s, integration through close contact with the west coast Japanese hub seems to have been intermittent at best. Instead, Southern Alberta’s Japanese settlers are appropriately understood as independently-minded “self-styled frontiersman” (2019, 4–5) in the words of Azuma. In their collective vision and through the institutions they created to foster Japanese identity, facilitate intra- and inter-community relationships, promote language, cultivate culture, and later, grow spirituality, they shaped the historical contours and dynamics of their settler projects as, “situationally adaptive, historically variable, modally diverse, and fundamentally transpacific, spanning multiple imperial spaces through the flexible mobility of [migrants], as well as the ideas and practices that they carried across sovereign national boundaries” (Azuma 2019, 4-5). Reflective of and building upon memories of upbringings and lives in Japan, individually and collectively they sought to represent their race, culture, enterprise, and families not in a formal ambassadorial sense, for example, to formally advocate kokutai (official ethics of emperor-centered national polity) ideology, even as some seem to have subscribed to it. Rather, their assertion of membership in an imperial Japanese imaginary as they perceived it empowered them in their efforts to carve a safe space in which they were also quietly proud of their heritage and efforts. Beyond the frontiers of Japan’s trans-Pacific colonial presence, and surrounded by sometimes hostile racist white settlers themselves seeking to assert British-cum-Canadian colonial sovereignty, clever, flexible, dexterous, as well as past-informed and future-facing self-reliance and independence was central to Japanese settlers’ material survival, economic and social well-being, and cultural as well as spiritual nourishment. Animating all of this in part was self-knowing, self-asserted membership of trans-Pacific communion, the imaginary of imperial Japan.

Locating southern Alberta’s Japanese

From transient labor-driven migration to experimentation with enterprise colonies, the establishment of the Japanese in southern Alberta was an offshoot of a wider pattern of Japanese economic settler and community-foundation activity across the Americas in the early decades of the twentieth century as described, for example, by Azuma (2019, 2). Coming late to imperial competition meant that Japan would develop less direct ways of controlling land and exploiting resources which were already claimed if not wholly developed by white colonial regimes at the expense of indigenous communities (Azuma 2019, 7). Instead, fast-evolving and highly adaptive mechanisms—for example, private immigration companies—created footholds to spearhead more complex diasporic movements of Japanese. By the end of the Meiji period (1868–1912), the Japanese government calculated that of the 185,316 overseas Japanese nationals, 41,546 resided in the continental Americas. Canada’s population made up one-quarter (9,275) with Alberta’s Japanese at 225 being the most populous east of Canada’s Pacific coast concentrations (Naikaku tōkei kyoku 1912, 70–72). Initially, in the first decade of the twentieth century, Japanese arrived either as dekasegi (‘transient migrant workers’), who sought work and wealth, ikkaku senkin (‘get rich quick’; see, for example: Kawahara, 2018; Stanlaw, 2006), or colonial entrepreneurs who aimed to develop large-scale agricultural commodity-based settlement colonies of the type more prevalent in Japanese Latin America (see, for example, Endoh 2009). These failed, but a number of individuals remained to establish communities in the hamlet of Hardieville located north of the region’s service hub Lethbridge, and some thirty kilometers to the southeast around the village of Raymond, with a smattering of individual families scattered more widely across the area.

The distance between Hardieville and Raymond was more than geographical. It reflected distinct industrial bases and work patterns with Raymond’s Japanese involved in farming from as early as 1903, especially sugar beets hence the region’s moniker of Sugar City, and Hardieville’s population employed in the area’s coal mines from 1909 (Interview: McCoughey, 2011).

It also emerged from different migration journeys: Raymond’s Japanese were brought in by Japanese emigration companies like the Nikka Yōtatsu Kaisha (‘Canadian Nippon Supply Company’) as labor to staff agricultural enterprises (Nomura 2012); Hardieville’s community was founded by Okinawan men in the Makishi Gang and the Fort Macleod Gang who left their employment with the railways and associated services, when in 1908 the United Mine Workers of America District 18 permitted Japanese membership, thereby enabling them to apply directly for employment in the coal mines (Interview: McCoughey 2011).

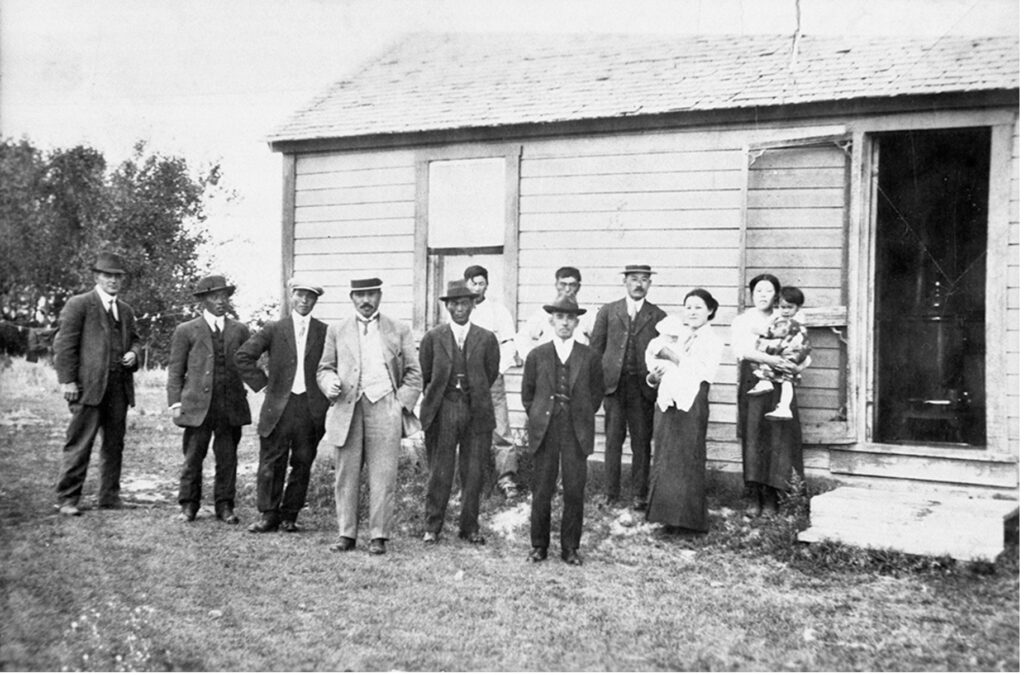

Central to the long-term success of both was the arrival of women. It may have been, as Kudo Miyoko (2021; see, chapter 6) in her oral history-based study suggests, that the first Japanese to work in what later became the province of Alberta were women in the sex industry from as early as the late nineteenth-century. In fact, it would not be until the 1910s that records reveal the first substantial numbers of women to settle in the area. The Nippon teikoku tōkei nenkan for 1916, for example, lists 25 women residents in the province of a total Japanese population of 186 (Naikaku tōkei kyoku 1917, 80–81). While recognizing differing registration and counting methods, the 1916 Canadian census details this population by locating sixteen women amongst 197 individuals in southern Alberta specifically by name, age, and region. They were far-outnumbered by men at a ratio of 1:5 (Dominion Bureau of Statistics 1916). The fact that all the women were in their late teens or older, at a time when one of the few ways that women could emigrate was as a ‘picture bride,’1 suggests that their impact far outweighed their numbers. Given that inter-racial marriage was all but unheard of, with just one Japanese-Dutch marriage,2 these women alone ensured that the erstwhile bachelor communities of southern Alberta transformed into sustainable self-reproducing settler-colonies. By 1926, the Japanese population of southern Alberta had grown to 300, with 162 individuals dispersed across farms around Raymond, 79 Okinawans in and around Hardieville, and the remainder scattered across the wider region.3

Minzoku Hatten: Building southern Alberta’s imperial Japanese imaginary

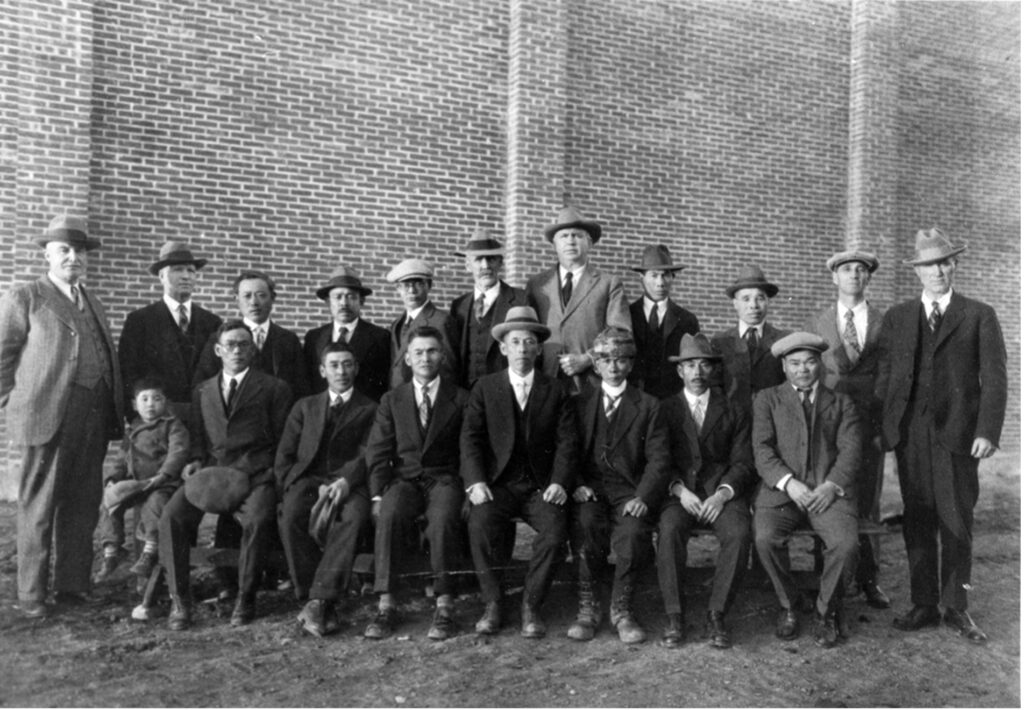

Let’s turn to two foundational institutional developments of the Japanese communities, the establishment of the Raymond Nihonjin Kyōkai (‘Japanese Association’; hereafter, Kyōkai) in 1914 and the Okinawa Dōshikai (‘Compatriots’ Association’; hereafter Dōshikai) in 1921. The Kyōkai and Dōshikai respectively coordinated Japanese and Okinawan households and their male heads. Insofar as these organizations were established according to long-term guiding aims and principles, they were constitutional bodies whose leadership structures delegated responsibility to offices held variously by each of the communities’ founding issei men. For example, the Dōshikai leadership included the kaichō (‘president’) of a small council that included a sajiyaku or kanjishoku (‘managing secretary’), and accounts clerk. As for the Kyōkai, the six founding members alternated the position of kaichō (Higa 2011, 3; Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970, 18). Each of the organizations collectively deliberated on issues concerning communal discipline, mutual welfare, community finances, the longer-term ethical, educational and cultural development of youth, and representations to wider society. In the Dōshikai, important decisions were made by democratic vote involving all household heads who comprised the membership. Over time, authority over these issues evolved networks of sub-organizations such as the seinendan (‘young men’s group’)in Raymond and the Dōshikai’s kyūsaibu (‘relief assistance department’) which addressed the precarity of Okinawans’ coal-mine work (Higa 2011, 11). In the case of the Raymond community, the Kyōkai acted as the foundation for the Buddhist Church into which it was incorporated in 1929, while the Dōshikai maintained a structurally more independent if closely affiliated position to the Buddhist institution into the postwar decades.

It may have been that the Kyōkai and Dōshikai drew on Japanese local self-governance organizational and authority frameworks which, at least as Fukutake Tadashi described of Meiji-era hamlets, included a similar structure representing household heads, led by a village head and Council (Fukutake 1967, 119–120). Yet, more than southern Alberta’s Japanese communal organizational structures, it was the organizations’ formally written aims that framed its residents’ Japanese trans-national identity. These lists of some five-to-six aspirational statements contextualized individuals’ rights and obligations within ethical, social, cultural and material considerations that both asserted membership of a trans-Pacific imperial Japanese imaginary and helped frame individuals’ engagement with the surrounding local white society. Let’s consider these more closely, and how the specific phrases and words chosen reveal the aspirations and anxieties animating them.

Of all concerns which the aims highlighted, it was the precarious situation of the Japanese as an ethnic enclave that is most conspicuous. In the case of the Dōshikai, it prioritised Nikka ryōkokumin no shinkō or “close friendship between the Japanese and Canadians.” The Kyōkai was more racially explicit in its call for Nippaku shinzen (‘Japanese-Caucasian goodwill’)(Higa 2011, 2; Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970, 18). The cultivation of neighborly relations was certainly common-sensical. It implicitly recognized that when the semi-arid environment of southern Alberta turned extreme and livelihoods were threatened, the favor of neighbors was imperative: “in that town [Raymond], they let people charge for a whole year until harvest time, and then they [the Japanese] would give them a box of apples or something to pay their debt. Amazing,” explained Mac (1927–2017) on his memories of the Raymond Mercantile, a general store established in 1901 and run by the Allen’s, a Church of Latter-Day Saints family whose reputation for good will ran high amongst Japanese (Interview: Nishiyama, 2013).4

Harmonious relationships could and did tip the balance in favor of economic survival, especially during the 1930s, which Japanese in Raymond recalled as the kunan jidai (‘period of suffering’) brought on by drought and the Depression (Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970, 25). Okinawans, too, defined this period stretching back into the 1920s ambivalently as the banyū jidai. This was a time of hardship requiring exceptional courage and “drastic measures [banyū].” For Okinawans, interaction with mainstream society took other forms, such as formal negotiation. For example, Okinawans—led by the bilingual Otomatsu Sawada, or the “Boss” as he was known—mobilized a two-pronged response involving both labor union and Vancouver-based Nihonjinkai mediation to appeal to coal mine directors over the unfair treatment of Okinawan workers concerning holidays and pay (Higa 2011, 15; Interview: McCoughey, 2011).5

The emphasis on ‘cooperation’ also anticipated how the Japanese position was precarious racially. At a fraction of one percent of Alberta’s population in the first four decades of the twentieth century, Japanese—widely dispersed—were far outnumbered by white society. This was especially the case with the British, who not only formed the province’s largest ethnic group, but as Howard Palmer observes of their dominant social and cultural influence, whose “unique British lifestyle…[and]…the intensity of [their] imperial orientation…had a strong impact on southern Alberta.”6 This included, as Palmer observed of the reception of Chinese and Japanese in Alberta in the 1900s and 1910s, the “condescension, contempt, or hostility [with which] British and Canadian workers regarded most East Asians” (Palmer 1985, 317). To be certain, in contrast to the Chinese, the Japanese in southern Alberta—fewer in number and far more dispersed—tended to be perceived as less threatening if unassimilable (Palmer 1980, 159; Palmer 1985, 317). Yet, Japanese self-awareness that white society, especially on the west coast, perceived their migration to Canada as the “Nihonjin mondai [‘Japanese problem’]” (‘Imin sōkan no gōgo’ 1914, 1) gives context to how southern Alberta’s Japanese—especially the first settlers—sought to navigate the racial environment into which they entered. In this light, Reiko’s (b. 1927) characterization of the relationship that Japanese nurtured with the wider Church of Latter-Day Saints community as “unique” was also a frank acknowledgement of where the Japanese were positioned in the Dominion province’s racial hierarchy. Sharing a story her father told of his early years in Alberta following his arrival in 1909, Reiko recalled how he and other Japanese were “treated very much like native Indians and then [the white community] found out later that the Japanese were trustworthy, honest, hard workers. So they changed their mind” (Interview: Nishiyama, 2013; Aoki, 2019). That efforts to promote inter-racial relations were successful even at the expense of demoting others is recalled by the authors of the Reimondo Bukkyōkai shi who appraised the Japanese as an “excellent race” (yūshū na minzoku), a fact evidenced by the foundational contribution they had on the agricultural cultivation of the region and the demonstrable “sense of trust” (shinraikan) that grew for the Japanese amongst the white population (Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970, 18–19).

Numerically few and racially surrounded, the encouragement of trans-Pacific migration had added importance. This took the form of sponsorship to bring over relatives in the Canadian-government sanctioned system called yobiyose (literally, ‘to call over’). Higa, a founding member of the Dōshikai, for example, describes his own yobiyose journey to Canada in 1920 from Yomitan in southern Okinawa at the behest of his father already established in southern Alberta (Higa 2011, 1). In the case of the Kyōkai’s leadership, migration was of such urgency that it made direct appeals to the Japanese Consul and Nihonjinkai in Vancouver with some success.7 Of course, efforts to ensure the replenishment of Raymond’s Japanese population was economically driven. As an agricultural settlement, labor to expand cultivation was expressly articulated as one of the Kyōkai’s founding aims, and it underpinned another aim which was to ensure the “establishment of the economic foundations of each of its members” (Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970, 18). By contrast, the economic focus of the Dōshikai’s founding aims in the 1920s was less on encouraging migration because demands for coal-mining labor were externally set and less elastic. Instead, they sought to mitigate the dangers of this work through communally coordinated risk management and response.

Trans-Pacific migration was also of paramount cultural significance. It is here where we see more directly how southern Alberta’s Japanese sought directly to reflect their membership of an imperial Japanese imaginary in their community construction. To be certain, a policy of kōminka was unviable in Britain’s white dominion. Defined by Sayaka Chatani (2018) as “‘imperialization’ or ‘imperial subjectification’ [that] sought to achieve racial and ethnic reprogramming, or ‘Japanization’” of subjugated colonial populations, kōminka structured and animated the inter-racial hierarchy and projection of authority throughout Japan’s formal empire (6). Yet, as we have seen, the Japanese settlers framed the hinterland setting of southern Alberta in terms of racial proliferation and ethnic continuity. In this sense, we might see the flipside of kōminka. Here, Japanization was not directed towards the white or indigenous populations. Rather it targeted the Japanese themselves which, in the aims of the Kyōkai, was described as minzoku hatten (racial/ethnic development) and which was to be affected through cultivation, recreation, and language in order to stoke “ethnic consciousness” (minzoku ishiki ni moe; Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970, 18). Applying the logic and expectation of inter-generational transmission, minzoku hatten implied progress, extending across generations replenished by migration directly from Japan, to very visibly become—in the words of the region’s main local English-language newspaper, The Lethbridge Herald—a “large Japanese colony who worship at Shrine of Buddha” (The Lethbridge Herald 1939, 7).

By the time that this report was published in 1939, the efficacy of Japanization and racial/ethnic development was ambiguous. Referring to Raymond’s Canadian-born Japanese children, its journalist-author observed, “they go to the public schools and high school and take on all the colors, hopes and ambitions of their Canadian environment,” with the older girls, notably, protesting against “Japanese ideas as to the subjection of women.” To claim as the Lethbridge Herald journalist did that “Japan in Alberta will not be a simple carbon copy of old Japan,” however, was perhaps to under-acknowledge and misunderstand the dynamic influence that imperial Japan might have had, one whose projection was technologically aided to promote transnational fluency:

Many of these Alberta Japanese have…radios. It is [this] that is their vital link with the homeland, particularly in the matter of war news. These school children, who know Japanese as well as English, rise at five in the morning to get stories, songs and news from the land of their parents (“Raymond has a Large Japanese Colony Who Worship at Shrine of Buddha,” 1939, 7).

In this light, Japanization was vital, urgent, sometimes unnoticed in the transformations it effected but swiftly transforming in ways that continually and very directly enfolded southern Alberta’s Japanese over and again into the latest geo-political situation of imperial Japan.8 In 1929, the Dōshikai, for example, sent a donation to fund the ceremony welcoming the arrival to Vancouver of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s training squadron (Higa 2011, 4–5).

There is another way to understand minzoku hatten if we turn our attention to how racial and especially ethnic ‘development’ might describe the idealized relationship of the individual to their community. In my interview with Reiko and Mac, Reiko described their parents and parents’ generation as “trustworthy, honest,” values of sincerity, diligence, and reliability that were not simply to do with one’s own personal qualities (Interview: Nishiyama, 2013). Rather, as measures of one’s responsibility to nurturing inter-personal relations, these were instrumental in securing the security and growth of the community. When Mac recollected how “we scrimped and we saved,” he not only alluded to values of frugality and discipline as virtues to explain how the hardships of the 1930s were endured. Rather, he narrated a form of personal independence, maturity, and ultimately success that chimes with what Chatani—in her observations of the aspirations of youth in the Japanese empire in the late Meiji and Taishō periods—identifies as risshin shusse (‘rising in the world’) (Chatani 2018, 37). Crucially, the autonomy that this might suggest is culturally calibrated, since in the “‘success’ paradigm” popularized at that time in Japan, “individuals’ morality and success were interlinked with the nation’s prosperity” (Chatani 2018, 37), or in the case of southern Alberta, the enhancement and advancement of the Japanese community and imperial imaginary within which it sat. All of this was framed within a dominant overarching image: “hard workers” said Reiko; “Japanese farmers are real hard workers,” specified Mac (Interview: Nishiyama 2013).

Far from being a matter-of-fact statement, Mac’s self-appraisal with specific reference to the Raymond Japanese community is provocatively over-determining in the appeals to race, culture, and history it implies. In the agrarian ideology that centrally shaped rural and colonial Japanese identity in the formal empire, kinrōshugi (hardworkism) was central to the belief of “many bureaucrats, urban intellectuals, and landlords” that, as “urban culture and industrial capitalism corroded the national spirit…agriculture was the basis for prosperous and harmonious nation, and that the purity of the nation was preserved in the countryside” (Chatani 2018, 25, 37). Bringing material and collective form to these ideals were villageyouth associations or seinendan, which, as Chatani observes, were the target of systematic organizational centralization and innovation in Japan’s formal empire from 1914 onwards. We’ll return to the seinendan below, but insofar as they alert us to an ideology of nōhonshugi or “agrarianism” that emphasized the “moral, ethical, and physical strength of farmers” and an “agrarian nationalism” whose aim it was to promote “moral training [and] self-cultivation” of youth (Chatani 2018 28–35), we begin to appreciate how such concerns informed the trans-Pacific imperial Japanese imaginary in southern Alberta.

To be certain, there is no evidence that either the Kyōkai or Dōshikai were affiliated organizationally, financially, or formally articulated aspiration with the metropolitan structures of the kind that Chatani describes in the empire’s formal colony of Taiwan, for example. Yet, the concerns she observes, especially in the ideologically-directed moral cultivation of youth, is instructive to understanding the overriding emphasis that both the Kyōkai and Dōshikai placed on moral rectitude in their aims, structures, and actions. In the case of the Kyōkai, Iwaasa observes how “the more responsible Japanese…attempted to do something about [moral problems]” which included the frequenting of prostitutes, for instance (Iwaasa 1978 20–21). Gambling was another thorny issue that particularly exercised the Dōshikai leadership who went so far as to establish the Tobaku torishimari iinkai (‘Committee to control gambling’) that coordinated household heads in an attempt to ban kakegoto no asobi (‘recreational gambling’; Higa 2011, 5). It is difficult to know to what extent, for instance, developments in Japan were directly influential in the thinking of southern Alberta’s Japanese such as the Boshin shōsho (Imperial Rescript on Diligence and Frugality) issued in Japan in 1908 which addressed “social ills” that seemed to afflict the health of the nation’s social body (Huffman 1998, 83; Gluck 1985, 177). But, perhaps the conceptualization of social problems, or shakai mondai as they were called in Japan, suggests a trans-Pacific contiguity of perception and especially communal institutional response. In this context, the transformation of a largely male economic migrant sojourner society into an economically productive, socially stable, and culturally vibrant settlement consisting of reproducing households becomes a deeply moral endeavor to develop, advance, and represent imperial Japanese identity as civilized. Here, we can identify a historical trajectory that is framed in terms of minzoku hatten and the panoply of structures and activities that evolved over the next decades like the seinendan, yayūkai (‘communal picnics’), Japanese language schooling, reading clubs and speech contests, and martial arts training.

Minzoku hatten also had a material dimension grounded in a particular conception of communal self-governance. Embedded within the aims of the Japanese and Okinawan communities was the concept of co-operative mutuality. In the Kyōkai’s founding statements, for example, sōgo fukushi (‘mutual welfare’) which expressly included ensuring each other’s social and individual well-being and economic viability, framed all other aims in the building of the Raymond community (Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970, 20). The founding principles of the Dōshikai similarly emphasized sōgo no kōfuku (‘mutual happiness’/‘well-being’), kaiin kyōtsū no rieki (‘the common benefit of members’), and sōgo fujo o mokuteki to suru (‘mutual aid as our [collective] aims’; Higa 2011, 2). In practice, this included what would become one of the Dōshikai’s most distinctive functions, a Relief Section (Kyūsaibu) that activated a co-operative financial assistance mechanism in times of hardship and illness (Higa 2011, 11). The primacy placed on cooperation to pool resources cannot be over-emphasized, not least because the principle of mutuality suggestively recalled homeland developments like the Hōtokusha (‘Society for Returning Virtue’) movement which became ubiquitous across rural Japan in the post-Russo-Japanese War years (Chatani 2018, 29). In this light, the integration of all member households into a co-operative body facilitated chihō jichi (‘local self-government’) for which, given the precarious racial and ethnic situation of southern Alberta’s Japanese communities, gave fiscal and administrative self-reliance a primacy of emphasis. Crucially, as with Hōtokusha ethics in Japan, mutuality was not only directed towards the sharing of welfare through the redistribution of wealth. Rather, it also sponsored the cultivation of an imperial Japanese identity through the funding of large-scale communal projects. In 1927, for example, the Okinawans completed the construction of their Gotaiten kinenkan hōru to commemorate the ascendancy to the throne of the Shōwa emperor. At $650, this was a costly venture that nonetheless was unanimously approved by the community and wholly self-financed by donations in installments with no external contributions (Higa 2011, 6–7, 9). The financing of the Raymond Buddhist Church agreed in a ‘Hundred Year Plan’ by members of Raymond’s Kyōkai similarly illustrates how the community overcame limited assets with one-hundred and twenty-four individuals pledging to donate $7,387.16 over the long term (Kawamura 1970, 138–139).

The Cultivation of Youth – Yamato damashii

At this juncture, let’s turn attention to how institutional innovations of southern Alberta’s Japanese Canadian communities evolved a social framework and cultural environment to spearhead the cultivation of an imperial Japanese cultural identity, with a focus especially on nisei (second generation) youth.

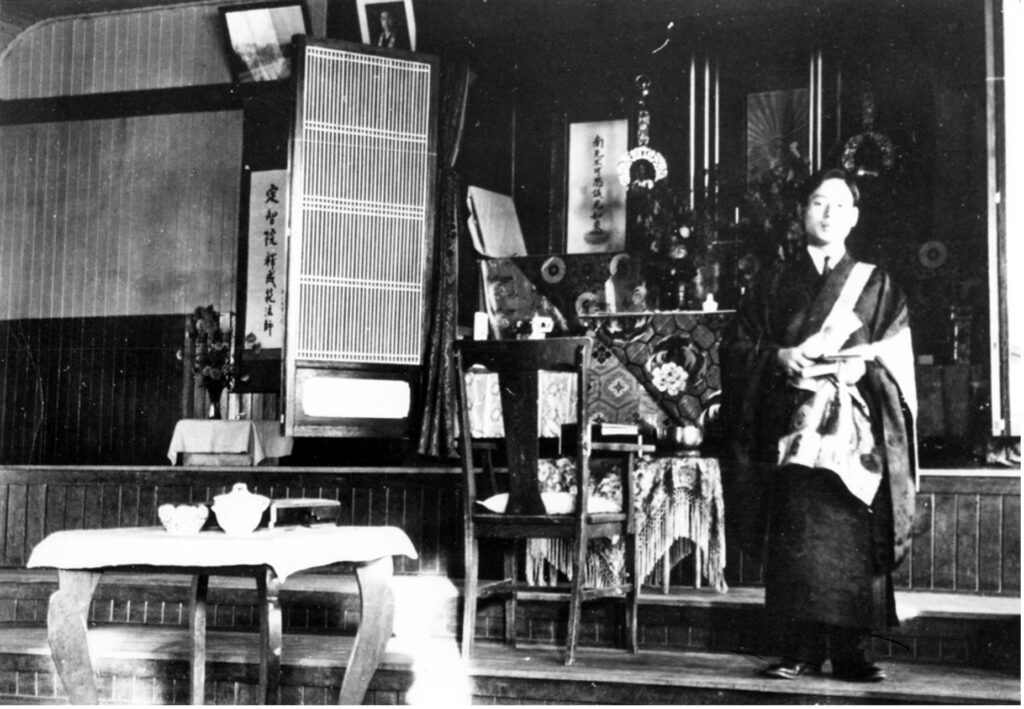

The opening of the Raymond Buddhist Church in 1929 marked a turning point. With the formal integration of the region into North America’s Jōdō shinshū (New Pure Land) ministry, southern Alberta’s Japanese Canadian communities became more directly integrated into Japan’s informal imperial projections in two inter-related ways. The first was trans-Pacific, and radiated outwards throughout the highly centralized Jōdō shinshū structure that controlled an extensive trans-national network of influence and authority across Japan’s formal and informal imperial territories and enclaves of Japanese around the Pacific rim (see: Zhao 2014; Harding, 2010; Rogers and Rogers 1990). In southern Alberta, this took the very immediate form of itinerant ministers whose placements were overseen directly from the Nishi Honganji headquarters in Kyoto. The ministrations of charismatic individuals like Reverend Kawamura Yūtetsu who arrived in 1934 were enthusiastically received by both Raymond’s Japanese and Hardieville’s Okinawans (Higa 2011, 12–13), and crucially, the newly shared Buddhist ritual structure and schedule would help bridge the racial divide between the two communities.

Critically, it should be noted that men like Kawamura and Ikuta Shinjō (1942–1951; Watada 1996, 170) who arrived in 1942 also energized a dynamic if controversial sense of membership in Japan’s imperial imaginary through their vocal imperial colonialist advocacy as seen, for example, in Kawamura’s establishment of the Kikoku dōshikai (‘Repatriate to Japan Association’) in the late 1930s. During the Second World War, it urged southern Alberta’s Japanese to return to their homeland in the expectation that Japan would emerge victorious (Interview: Sakumoto 1977; Kawamura 1988, 158). It had only been a few years earlier that Kawamura similarly proposed that Raymond’s Japanese wheat farmers relocate en masse to Manchuria, going so far as to approach the Japanese Consulate unsuccessfully with his proposal (Kawamura 1988, 6; Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970, 24–25).

There is another way that the establishment of Jōdō shinshū reveals how southern Alberta’s Japanese communities became more institutionally integrated into the structural innovations of Buddhism in North America, and in turn, Japan’s informal imperial projections. Let’s focus specifically on Raymond’s Japanese, since although similar developments would come to shape the Okinawan community, the contentious dispersal of Okinawans into farming as a result of the closing of Coal Mine No. 6 in the 1930s, and their geographical distance from the center of southern Alberta’s Buddhist innovations, meant that the Dōshikai—rather than the Buddhist Church—continued to be the focus of institutional transformation beyond the period under consideration in this article.

By the late 1930s, a complex inter-generational and gender-segregated conception of the Buddhist Church had emerged whose aims to mold the up-and-coming nisei were as novel as they were familiar. At the heart of the structure was the seinendan (officially, the Bukkyō Seinendan or Bussei, Young Men’s Buddhist Association) with twenty some members, established in 1928, and later, from the early 1930s, a female equivalent, the Young Women’s Buddhist Association (YWBA). In both, membership consisted of unmarried nisei who represented one step in a hierarchy of age-cohorts, including at the younger end, a shōnendan (‘boy’s association’) for teenage boys of junior-high and high-school age, and the sōnendan (‘adult men’s group’) for married men. Males from longstanding and leading families, for example those who founded the community, formed the Bukkyōkai, the Church’s executive council led by a president, which in 1929 replaced the Raymond Nihonjin Kyōkai. For their part, women would leave their membership of the YWBA and join the Fujinkai (Housewives association). This highly structured organization of nisei envisaged a trajectory of lay and spiritual community leadership since, when individuals reached the appropriate age, they would enter into the next higher group and assume responsibilities over the training of their juniors, for example, seinendan responsibility to run Dharma school classes (Buddhist Sunday School; Reimondo Bukkyōkai, 1970, 24–25; Watada, 1996, 81).

Southern Alberta’s seinendan wasn’t always Buddhist. Known originally as the Meidō seinenkai, the origins and aims of this organization are hazy. According to Fujioka and Iwaasa, it was established by a retired visiting priest of the Japanese Methodist Church, Ōyama Ukichi, who opened a night school to develop young men’s English proficiency (Fujioka 2010, 129; Iwaasa 1978, 37). Although this initiative was in keeping with the primacy of value given by Japanese Christians to zero-sum assimilation in which Japanese-ness is exchanged for Canadian-ness, the Reimondo Bukkyōkai shi describes a different emphasis of purpose. Highlighting the youthful age of incoming Japanese settlers, English language study was framed not in terms of assimilation, but as central to self-cultivation and recreation in the forging of an ardent Japanese ethnic consciousness (Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970, 19). The importance of this aim is difficult to overstate, because this emphasis of concern helps to contextualize later efforts and intentions of parents. Take, for example, Japanese language education for nisei which was introduced by Kawamura and his wife Yoneko, and which was facilitated by the seinendan (Kawamura, 1988, 4). Their instruction, informal and unpaid, addressed concerns of the older generation for language retention (Fujioka, 2010, 138). As in Raymond, the Okinawan issei were similarly exercised by this “great worry [ōinaru nayami].” Higa’s memoirs, for instance, emphasizes how parents “put their heart and soul [seikon o tsukushite]” into ensuring that children would not lose the ability to communicate with family in Japan and connections with the imperial homeland: indeed, the graduation ceremony of the Japanese language school established in 1929 by the Okinawans doubled up with formal celebrations to mark the emperor’s birthday in 1937 (Higa 2011, 15). The effort to run the school should not be underestimated: sponsored through individuals’ contributions, finances were nonetheless scarce especially during the long years of the Great Depression making it difficult to retain teachers (Higa 2011, 14).

Education was not limited to language. The introduction of kendō by Nagatomi Shinjō, resident priest from 1930–1934 was more than as a pastime. Along with judo, which would flourish notably during and after the Second World War, these sports whose training was located in the basement of the Raymond Buddhist Church building, were formally incorporated in 1943 into children’s education at the behest of Reverend Ikuta and backed by the Bukkyō-kai leadership (Watada 1996, 142; Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970, 11). In the case of kendo, it was reported that against the backdrop of the Sino-Japanese conflict, southern Albertan “seinentachi [‘young men’]… ‘were intensively training to prepare’” (Reimondo daiyori 1931, 4).

In bringing attention to Nagatomi’s and Ikuta’s initiatives to introduce martial arts—and to this we might add odori (traditionalistic Japanese dancing) for women by Mrs. Kawamura (Watada 1996, 137)—we are alerted to a powerful form of education. Accordingly, ideological inculcation was filtered through ritualized inter-personal manners (for example, bowing), specialist vocabulary in Japanese, hierarchical teaching structures (Sellers-Young 2001), and especially in the comportment martial arts and odori instilled when the body is still and in its formalized techniques and movements. This had the potential to discipline the body in ethnically gendered ways, as well as to cultivate an embodied fluency of masculine or feminine participation in and membership of an imperial Japanese imaginary.

It should be noted that martial arts weren’t the only form which sport took. Baseball and athletics were also central to activating the imperial imaginary. For example, at community ‘picnics’ that brought together Japanese from around the region in the late 1920s and 1930s, it was recalled that while Hardieville’s Okinawans were victorious in relay races, they could never defeat Raymond’s baseball team. Although the yayūkai, as these were more officially known, were light-hearted if often dangerously drunken events, the undōkai (athletic meets) that were one of its most popular activities were steeped in ideological meaning. Participants were greeted by decorations which literally spelled out in banners the phrase Yamato damashii, the “spirit” or “soul of the Yamato [ideologically-powerful term for Japan] people”. As is collectively recalled of one moment in 1928, declarations extolling Yamato damashii were all the more potent because they were led by Okutake Tomomi, an Imperial Japanese Navy veteran of the Russo-Japanese War who was also a First World War veteran serving for the Dominion of Canada (Higa 2011, 8). The framing of sport and the community bonds it propagated as a patriotic expression profoundly colored the friendship and fraternity of what for Higa were “memories of a lifetime which I can never forget” (Higa 2011, 8).

Southern Alberta’s imperial Japanese imaginary

In the closing years of the First World War, Sugimoto Kichimatsu (“Attestation Paper, Canadian Over-seas Expeditionary Forces – Sugimoto Kichimatsu” 1916) and Suda Teiji (“Attestation Paper, Canadian Over-seas Expeditionary Forces – Suda Teiji” 1916) were killed in action in northern France. Fighting alongside six others from southern Alberta’s Japanese and Okinawan communities, they were part of the 222-strong contingent of Japanese who joined the Canadian Dominion’s war effort (see, Government of Canada).

In this light, it might seem logical to conclude, that the Japanese made a “simple transfer of allegiance to King and country from Emperor and empire” (Iwaasa 1978, 27–28). Legally, through Canadian naturalization to which southern Alberta’s issei men and women committed themselves, and which guaranteed their children’s Canadian citizenship by birth, this transfer did take place. Yet, this is to oversimplify and even ignore a far more complex navigation of layered and conflicting identities, what Terry Watada in his study of Canadian Buddhism, observes as a dualistic mindset shaping “Japanese Canadian culture…steeped in the Meiji paradox of embracing Western technology while fiercely adhering to Japanese tradition” (Watada 1996, 60). Far from suggesting easy accommodation of the Canadian environment, he posits the compelling if unexplored suggestion that adaptation was limited to “the most superficial level” (Watada 1996, 97-98). What then of the Japanese in southern Alberta, a small, at times materially poor yet ethnically proud community isolated—”alienated” (sogai sare; Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970, 18) in the words of Raymond’s Japanese—from the more extensive Japanese social and cultural infrastructures on the west coast, encircled predominantly by settler-colonialist pioneers of the Anglo-white race? Indeed, for men like Sugimoto, the fact that their First World War service was not their first conflict—many had served as imperial Japanese forces in the Russo-Japanese War a decade earlier—alerts us to what was an ongoing negotiation of ethnic identities, cultural values, imperial loyalties, and social aspirations. To illustrate, it comes as no surprise in this context that in their opening of their communal hall to commemorate the enthronement of the Shōwa emperor, for example, it was Okutake Tomomi—veteran of both the Russo-Japanese and Canadian First World War conflicts—who led the Okinawan community in their ceremonial bow facing towards the southwest where the imperial metropolitan heartland lay, the singing of the Japanese national anthem Kimi ga yo, and the banzai cheers to the emperor (Higa 2011, 6–7, 9).

Lest the impression be given that the influence of southern Alberta’s imperial Japanese imaginary was total and exclusive, one further example suggests how identity, loyalty, values, and aspiration were highly complex and even apparently contradictory. From her collection of her father’s possessions (Sassa, 2013; Interview: Sassa 2013), Pat Sassa showed me a number of postcards: one featured him next to a fellow soldier, both in uniform with the Dominion forces maple leaf badge adorning their collar tips; another was of St. Paul’s Cathedral which he visited during his stay in Britain; and most unique was one received from King George V and Queen Mary with an inscription signed by them on the back that read: “With our best wishes for Christmas 1914. May God protect you and bring you home safe.” Pat then unfolded a letter dated 3 April 1944, directed to the Council of the Town of Coaldale asking for permission to buy land to build a new Buddhist temple. Next to his signature—“T[omomi]. Okutake”—a postscript read, “I am who served first great war in Canadian army and have responsible to good conduct of our members. I am the father of a soldier now serving overseas with Canadian army [sic].” On their own, these sources could and did narrate a story of membership in the imperial British imaginary, whose values included the defense of the empire as demonstrated by Okutake’s voluntary First World War military service, martial camaraderie, symbols of the British imperium and homeland, deference to the institutions of governance and masculine personal responsibility, and the bonds of King and country. To be certain, Okutake’s letter tactically asserts personal authority through the deployment of his military history to assert his Canadian and British Empire credentials. I would also argue, however, by emphasizing his belonging to a British imperial imaginary, he also affirmed his, his family’s, and his community’s place within an imperial Japanese imaginary.

Regarding the aspirations of southern Alberta’s Japanese Canadians in the decades prior to the Second World War, it is germane to turn to Eiichiro Azuma’s (2005) study of issei immigrant identity and their concerns over their nisei children’s “ambiguous position” which was to be “caught between the generally polarized notions of what was Japan and what was America” (132). To this end, he deploys a binary conceptual model that “[distinguishes] race/nation (minzoku) from state (kokka)” (Azuma 2005, 132). Let’s consider this more closely:

The notion of the Nisei’s future development…revolved around this very distinction. Without dispute, according to Issei thought, the Nisei were Japanese in terms of race and nationality, yet they were also full-fledged Americans in terms of citizenship. The Japaneseness of the Nisei derived from their ‘natural’ attributes, devoid of ‘political’ ties to the Japanese state. That is not to say that the Issei did not wish their children to have sympathy or an affinity with imperial Japan, but their American citizenship took precedence (Azuma 2005, 132).

It is at this juncture where Azuma’s approach counter-intuitively observes how this “eclectic interpretation” has profound “moral effect,” one which split Japanese identity so that, as “an extension of the Japanese race/nation, albeit the Japanese state,” nisei would “hold competitive edge over other minorities under white hegemony” (Azuma 2005, 133). In other words, it is precisely because “the core of their spirit still lay inside Japan” that “Nisei’s racial/national strengths’” would be “enhanc[ed]…making them better U.S. citizens” (Azuma 2005, 132), what Kumei in her study of Japanese language education in prewar west-coast America identified as the imperative “to become citizens valuable to the United States” (Kumei 2002, 111).

As this preliminary exploration of the traces of southern Alberta’s imperial Japanese imaginary has suggested, the distinction was not always clear as Azuma posited between, on the one hand, the ethics of kokka—the ideology of Japan’s emperor system and its attendant rituals – and, on the other, minzoku morality—a “racial subjectivity” in Azuma’s words (2005, 133), which instilled values of right and wrong in action, thought, and spirit especially vis-à-vis others and the wider community. Far away from Japan’s formal empire, and distant from the economic, diplomatic, social, cultural, and ideological infrastructure of Japanese community hubs emerging along North America’s Pacific coast, southern Alberta’s contacts with either imperial Japan’s North American west-coast outposts, as well as it’s metropolitan center, were sporadic. Even after Buddhism officially established itself in the 1930s, consistency of message and practice could be haphazard, not least because the community itself was so dispersed, individuals and families often struggling simply to survive in isolated locales. In its make-shift, make do emergence constructed from the ground up shaped through and reflecting homeland memories and ideals of their Japanese and Okinawan issei makers, these might be profoundly potent in their efficacy, all the more so given the range of influences these settlers had to navigate also as new members of the imperial British imaginary that shaped Canada’s nation-state building project. More research on these competing influences is certainly needed. Yet, so far as traces will disclose and a new historical position can be proposed, it seems these settlers emulated lived experiences transported from another life and past in Japan. What they built as our exploration of institutional innovation suggests was long-term in intent and future-facing in aspiration. Relying less on precisely replicated templates of the empire they remembered transposed onto the Canadian prairie than bespoke expressions, they expressly and actively aspired to effect Japanese racial progress, cultivate Japanese identity, and construct institutional forms, all of which affirmed affiliation with and membership of an imperial Japanese imaginary; embodied, affective, aesthetic, linguistic, spiritual, and cultural as Japanese and as Canadians.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to extend my deep gratitude to the many individuals who shared their memories in oral history interviews and documents, and to local stakeholder partnerships whose collaboration and assistance have been instrumental: Nikka Yuko Japanese Garden, Nikkei Cultural Society of Lethbridge and Area, Galt Museum and Archives, Okinawa Cultural Society. I’d like to acknowledge the University of Plymouth Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Business whose funding and support have made the nisei oral history pilot project possible, as well as the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Insight Grant—Transforming Canadian Nikkei (Nikkei Memory Capture Project)—which funded the images for this article. A very special thank you goes to Carly Adams, the University of Lethbridge, and the Centre for Oral History and Tradition for their encouragement, advice, and friendship. My sincere appreciation goes to Gideon Fujiwara, Akira Ichikawa, George Kamitakahara, Tosh Kanashiro, April Matsuno, Marlene McCoughey (nee Makishi), Laura A. Sugimoto, Suzuki Ai, Darcy Tamayose, David Tanaka, Masaye Tanaka, and Roy Urasaki for their assistance and generosity.

References

Aoki, Darren J. 2019. “Assimilation – On (Not) Turning White: Memory and the Narration of the Postwar History of Japanese Canadians in Southern Alberta.” Journal of Canadian Studies Vol. 53, No. 2 (Spring): 238–269.

Aoki, Darren J. 2020. “Remembering ‘The English’ in four ‘memory moment’ portraits: navigating anti-Japanese discrimination and postcolonial ambiguity in mid-twentieth century Alberta, Canada.” Rethinking History Vol. 24, No. 1: 29–55.

Azuma, Eiichiro. 2005. Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America. New York and Oxford: University of Oxford Press.

Azuma, Eiichiro. 2019. In Search of Our Frontier: Japanese America and Settler Colonialism in the Construction of Japan’s Borderless Empire. Oakland: University of California Press.

Caldarola, Carlo. 2007. “Japanese Cultural Traditions in Southern Alberta.” In Sakura in the Land of the Maple Leaf: Japanese Cultural Traditions in Canada. Ed. Ban Seng Hoe. Gatineau: Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation: 5–72.

“Attestation Paper, Canadian Over-seas Expeditionary Forces – Suda Teiji.” 1916. Library and Archives of Canada RG 150. Accession 1992-93/166, Box 9407-39, Item No. 257696.

“Attestation Paper, Canadian Over-seas Expeditionary Forces – Sugimoto Kichimatsu.” 1916. Library and Archives of Canada RG 150. Accession 1992-93/166, Box 9410-4, Item No. 257825.

Chatani, Sayaka. 2018. Nation-Empire: Ideology and Rural Youth Mobilization in Japan and Its Colonies. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1916. “Census of the Prairie Provinces, 1916: Alberta, Districts 38–0” https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/census/1916/Pages/about-census.aspx. Accessed 20 April 2022.

Dominion Bureau of Statistics. 1926. “Census of the Prairie Provinces, 1926: Alberta, Districts 39–54” https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/census/1926/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed 20 April 2022.

Endoh, Toake. 2009. Exporting Japan: Politics of Emigration to Latin America. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Fujioka, Toshihiko. 2010. “Kanada, minami Arubaata ni okeru Nikkeijin shakai no shūkyō: toku ni Bukkyōkai no sōritsu to sono igi to megutte [The religion of Nikkei society in southern Alberta, Canada: on the meaning of the establishment of the Buddhist Church especially].” Tabunka kyōsei kenkyū nenpō (Annual Report on Multi-cultural Research No. 7: 123–140.

Fukutake, Tadashi. 1967. Japanese Rural Society. Trans. Ronald P. Dore. Ithaca: Cornwell University Press.

Gluck, Carol. 1985. Japan’s Modern Myths: Ideology in the Late Meiji Period. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985.

Government of Canada. “Japanese Canadian War Memorial.” https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/memorials/national-inventory-canadian-memorials/details/4217. Accessed 22 April 2022.

Harding, John. 2007. “Expanding Notions of Buddhism: Influences beyond Meiji Japan.” Pacific World. Vol. 9, Fall: 189–204.

Harding, John S. 2010. “Jodo Shinshu in Southern Alberta: From Rural Raymond to Amalgamation’. In Wild Geese: Buddhism in Canada. Ed. by John S. Harding, Victor Sogen Hori, and Alexander Soucy. Montreal & Kingston, London, Ithaca: McGill-Queen’s University Press: 134–167.

Higa, Shūchō. 2011. Kanada-Arubaata shū ni okeru Okinawa Kenjinkai no ayumi (History of Okinawan Kenjinkai in Alberta, Canada; unpublished). Transcribed and annotated by Higa Shūchō and Roy Urasaki.

“Hisaji Sudo.” My Heritage. https://www.myheritage.com/names/hisaji_sudo. Accessed 8 April 2022.

“House Passes Burnet Immigration Measure.” 1914. Cornell Daily Sun. 5 February: 8.

Huffman, James L. 1998. “Home Ministry.” In Modern Japan: An Encyclopedia of History Culture and Nationalism. New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc.: 83.

Ichikawa, Akira. 1994. “A Test of Religious Tolerance: Canadian Government and Jodo Shinshu Buddhism during the Pacific War, 1941–1945.” Canadian Ethnic Studies Vol. 26, No. 2: pp. 46–69.

“Imin sōkan no gōgo [The Immigration Commissioner’s Bluster].” 1914. Tairiku Nippō, 14 February: 1.

Iwaasa, David. 1978. “Canadian Japanese in Southern Alberta: 1905-1945 [BA Dissertation: Lethbridge, Canada, 1972].” In Two Monographs on Japanese Canadians. Ed. Roger Daniels. New York: Arno Press: 1–99.

Izumi, Masumi. 2020. Nikkei Kanadajin no idō to undo: shirarezaru Nihonjin no ekkyō seikatsushi [Japanese Canadian Movements: Unknown History of Japanese Lives Crossing Boundaries]. Tokyo: Takanashi Shobō.

Kawahara, Norifumi. 2018. “Kanada e no imin [Migration to Canada].” In Nihonjin to kaigai ijū: imin no rekishi, genjō, tenbō [The Japanese and Overseas Migration: The History of Migrants, Their Current Situation, and Prospects]. Ed. Nihonjin imin gakkai (The Japanese Association for Migration Studies. Tokyo: Akashi shoten: 99–117.

Kawamura, Leslie. 1970. “History of the Raymond Buddhist Church, 1929-1969.” In Reimondo Bukkyōkai shi [History of the Raymond Buddhist Church]. Ed. Reimondo Bukkyōkai. Raymond Buddhist Church, 1970: 131–146.

Kawamura, Yūtetsu. 1988. Kauboi songu no sato – Kanada, Arubaata shū (Hometown Cowboy Song – Alberta, Canada). Kyoto: Dōbōsha.

Klein, Christina. 2003. Cold War Orientalism: Asian in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945–1961. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kudo, Miyoko. 2021. Picture Brides – Shakonsai. Originally published in 1983. Trans., Fumihiko Torigai. Burnaby: Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre. https://centre.nikkeiplace.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Picture-Brides-Miyoko-Kudo.pdf. Accessed 8 April 2022.

Kumei, Teruko. 2002. “‘The Twain Shall Meet’ in the Nisei? Japanese Language Education and U.S.-Japan Relations, 1900-1940.” In New Worlds, New Lives: Globalization and People of Japanese Descent in the Americas from Latin America in Japan. Ed. Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, Akemi Kikumura-Yano, and James A. Hirabayashi. Stanford: Stanford University Press: pp. 108–125.

LDJCA History Book Committee. 2001. Nishiki [Brocade]: Nikkei Tapestry: A History of Southern Alberta Japanese Canadians. Lethbridge: Lethbridge and District Japanese Canadian Association.

Lu, Sidney Xu. 2019. The Making of Japanese Settler Colonialism: Malthusianism and Trans-Pacific Migration, 1868–1961. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mardon, Ernest. G. and Mardon, Austen. 2011. The Mormon Contribution to Alberta Politics. Edmonton: Golden Meteorite Press.

McDonald, Kate. 2017. Placing Empire: Travel and the Social Imagination in Imperial Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Naikaku tōkei kyoku [Cabinet Statistics Bureau]. 1912. “Gaikoku zairyū honpōjin kosū oyobi danjo betsu, Meiji 44 nen 12 gatsu 31 nichi [Japanese nationals resident in foreign countries and sex breakdown, 31 December 1911].” Nihon teikoku tōkei nenkan dai sanjūichi [Statistical Yearbook of the Japanese Empire, Number 31].

Naikaku tōkei kyoku [Cabinet Statistics Bureau]. 1917. “Gaikoku zairyū honpōjin kosū oyobi danjo betsu, Taishō 4nen 6 gatsu 30 nichi [Japanese nationals resident in foreign countries and sex breakdown, 30 June 1916].” Nihon teikoku tōkei nenkan dai sanjūigo [Statistical Yearbook of the Japanese Empire, Number 35].

Nakayama, Jinshirō. 1918. Kanada dōhō hattenshi [History of the Progress of Japanese Compatriots in Canada] Vol. 2. Tokyo: Tairiku Nippōsha.

Nomura, Kazuko. 2012. “They Who Part Grass: The Japanese Government and Early Nikkei Immigration to Canada.” Unpublished Masters of Arts Thesis, University of Manitoba, Canada.

Okinawan Cultural Society. 2000. Biographies of Issei from Okinawa to Southern Alberta. Unpublished.

Palmer, Howard. 1980. “Patterns of Racism: Attitudes Towards Chinese and Japanese in Alberta 1920–1950.” Histoire Sociale- Social History XIII:25, May: 137–160.

Palmer, Howard. 1985. “Patterns of Immigration and Ethnic Settlement in Alberta: 1880–1920.” In Peoples of Alberta: Portraits of Cultural Diversity. Eds. Howard and Tamara Palmer. Edmonton: Pica Pica Press: 309–333.

Palmer, Howard. 1985. “Strangers and Stereotypes: The Rise of Nativism – 1880–1920.” In The Prairie West: Historical Readings. Eds. R. Douglas Francis and Howard Palmer. Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books: 1–27.

Palmer, Howard and Palmer, Tamara. 1985. “Introduction.” In Peoples of Alberta: Portraits of Cultural Diversity. Eds. Howard and Tamara Palmer. Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books: vii–xvi.

“Raymond has a Large Japanese Colony Who Worship at Shrine of Buddha: Priest from Japan is Kept Busy – Impressive Temple Ritualism.” 1939. The Lethbridge Herald, 30 January: 7.

Reimondo Bukkyōkai (Raymond Buddhist Church). 1970. Reimondo Bukkyōkai shi [History of the Raymond Buddhist Church]: 1929–1969. Raymond: Raymond Buddhist Church.

“Reimondo daiyori: seinendan katsudō [Raymond News: seinendan activities].” 1931. Tairiku Nippō, 18 December: 4.

Rogers, Minor L. and Rogers, Ann T. 1990. “The Honganji: Guardian of the State (1868–1945).” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, Vol. 17, No. 1, March: 3–28.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 1941–1949. “Japanese Conditions – Canada – Generally.” British Columbia Security Commission. National Archives of Canada RG36/27/30/F1613.

Sassa, Pat. 2013. Tomomi Okutake personal artefact collection.

Sellers-Young, Barbara. 2001. “‘Nostalgia’ or ‘Newness’: Nihon Buyō in the United States.” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 12:1: 135–149.

Stanlaw, James. 2006. “Japanese emigration and immigration: from the Meiji to the modern.” In Japanese Diasporas: Unsung pasts, conflicting presents, and uncertain futures. Ed. Nobuko Adachi. London and New York: Routledge; 35–51.

Sunahara, Ann Gomer. 1977. “Ann Sunahara’s Japanese Oral History Project (Interviewer: A.G. Sunahara).” Glenbow Museum Archives RCT831.

Sunahara, Ann Gomer. 1981. The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians During the Second World War. Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, Publishers.

Watada, Terry. 1996. Bukkyo Tozen: A History of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism in Canada, 1905-1995. Toronto: Toronto Buddhist Church.

Zhao, Dong. 2014. “Buddhism, Nationalism and War: A Comparative Evolution of Chinese and Japanese Buddhists’ Reactions to the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945).” International Journal of Social Science and Humanity. Vol. 4, No. 5, September: 372–377.

Oral History Interviews

McCoughey, Marlene. 2011. Interviewed by Darren J. Aoki 10 March.

Nishiyama, Mac and Reiko. 2013. Interviewed by Darren J. Aoki 27 March.

Urasaki, Roy. 2011. Interviewed by Darren J. Aoki 15 March.

Sakumoto, Seiku. 1977. Interviewed by Anne G. Sunahara 13 August. In “Ann Sunahara’s Oral History Project.” Calgary: Glenbow Museum Archives RCT 831–19.

Sassa, Pat. 2013. Interviewed by Darren J. Aoki 27 March.

Notes:

- See, for example: “Iwaasa, Kojun & Ito” and “Koyata, Takejiro & Isa” (LDJCA History Book Committee, 2001, 203–206, 261–262).

- Hisaji Sudo married Valentina Philomena Leontiene Coppieters in 1915 (“Hisaji Sudo”)

- The total number of Japanese in Alberta in 1926 was 452 (Dominion Bureau of Statistics 1926)

- See, also Mardon and Mardon (2011, 13–14).

- The difficulties of the banyū jidai became existential when, following the closure of Hardieville’s Coal Mine No. 6 in 1935, the collective ethos that the Okinawans had developed broke down resulting in the split of the community upon the decision of some to move into agriculture and relocate away from Hardieville, the centre of the original Okinawan settlement (Higa 2011, 4–5).

- In 1921, the total population of Alberta was 588,454. British made up nearly 60 percent (351,820). The next most populous groups by ethnic origin were Scandinavians (7.56 percent) and Germans (6.01 percent). The largest non-European population was the First Nations (14, 557 people; 2.47 percent; Palmer 1985; Palmer and Palmer 1985, xv–xvi, 9).

- According to the Reimondo Bukkyōkai shi, around fifty came as yobiyose migrants (Reimondo Bukkyōkai 1970, 18–19).

- The timing of the Lethbridge Herald report is interesting. Occurring when imperial Japan was violently advancing in China, the tone of the report is benign. It even references a speech made by a young Japanese Canadian woman defending Japan’s ambitions. As Palmer observed, the dispersal of Japanese across vast rural areas and their small numbers, as well as efforts to cultivate amicable relationships with neighbours meant that anti-Japanese hostility seemed largely absent, a situation reflected by the absence of anti-Japanese legislation in Alberta. Instead, racial hostility came from Chinese communities, which heightened from 1937 into the early Second World years (“Raymond has a Large Japanese Colony Who Worship at Shrine of Buddha” 1939, 7; Palmer 1908 145–146; Iwaasa 1978 45-47, 50–51).