Abstract: This article seeks to explain the disparity in treatment received by two groups of terrorists in 1930s Japan. First, Inoue Nisshō, head of a band of terrorist assassins popularly known as the Blood Oath Corps (Ketsumeidan), received lenient, if not supportive, treatment from powerful forces in Japanese society even before he surrendered to police on 11 March 1932. Second, a group of young Imperial Army officers and their troops attempted a coup d’état on 26 February 1936. However, in the aftermath of the failed coup, the leaders were arrested and, shortly thereafter, executed by firing squad. Both Inoue and his band of assassins as well as the young army officers were proponents of a movement known as the “Shōwa Restoration” (Shōwa Isshin). Despite the goal they shared in common, and despite the assassinations of important Japanese figures they both carried out, why was the treatment they received at the hands of the Japanese authorities so completely different?

Key Words: Assassination, Inoue Nisshō, Shōwa Restoration, Blood Oath Corps Incident (Ketsumeidan), 26 February 1936 Incident, Emperor Hirohito, Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro, Tōyama Mitsuru, General Araki Sadao, Prince Chichibu, Prince Takamatsu, Tokugawa Yoshichika, Imperial Way faction and Control faction (in the Imperial Army)

Introduction

In the course of writing, Zen Terror in Prewar Japan: Portrait of an Assassin (Rowman & Littlefield, 2020), I encountered a historical anomaly that, at the time, I was unable to resolve. In part, this was because the focus of my book was on the role Zen Buddhism played in the Blood Oath Corps Incident (Ketsumeidan Jiken) of early 1932. In addition, I lacked sufficient factual knowledge to reach a conclusion. While I still cannot claim to have definitive proof, I have now gathered sufficient, additional information to make what I call an “educated hypothesis” leading to a resolution of the anomaly I encountered. At the very least, it is a hypothesis open to either verification (or revision) as further research becomes available.

The anomaly I refer to, simply stated, is this: how is it possible to explain the disparity in treatment received by two groups of terrorists in 1930s Japan. In the first instance, Inoue Nisshō (1886-1967), head of a band of terrorist assassins popularly known as the Blood Oath Corps (Ketsumeidan), received almost unbelievably lenient, if not supportive, treatment from powerful forces in Japanese society even before he surrendered to police on 11 March 1932. In the second instance, a group of young Imperial Army officers and the troops under their command attempted a coup d’état on 26 February 1936. However, following the coup’s failure, the coup leaders were arrested and subjected to secret military Courts-martial shortly after which they were all executed by firing squad.

While the two incidents in question were discrete events, separated by some four years, it is noteworthy that Inoue and his band of assassins and the young officers were both proponents of a movement known as the “Shōwa Restoration” (Shōwa Isshin). Despite the goal they shared in common, and despite the assassinations of important Japanese figures they carried out, the treatment they received at the hands of the Japanese authorities was completely different. Why did this occur?

What was the Shōwa Restoration?

As the first step in answering this question, we need to understand something of the nature and goals of the Shōwa Restoration. In name, it appears to mimic the Meiji Restoration that had occurred more than sixty years earlier in 1868. This time, however, Emperor Shōwa, i.e. Hirohito, had been on the throne since 1926. Thus, there was no need for him to be restored to the throne.

Emperor Hirohito

Shōwa Restoration advocates, however, had a different goal in mind, i.e. the restoration of total political, economic and military power to Emperor Hirohito and those members of his court circle and military leaders deemed appropriately loyal. This goal had become necessary in the eyes of Restoration advocates due, in the first instance, to the emergence of parliamentary democracy in the Taishō era (1912-1926). In the eyes of Restoration advocates, the political party-based cabinets that resulted were composed of politicians corrupted by their close financial ties to, and dependence upon, Japan’s industrial combines, i.e. zaibatsu.

Both politicians and zaibatsu, as well as some members of Hirohito’s court circle, were said to follow their narrow self-interests while the majority of the Japanese people were left to suffer, especially in the rural areas where some 44% of the farming population languished as landless tenants. Their poverty was especially acute in the wake of the Great Depression of 1929 as well as repeated poor harvests in northern Japan. Shōwa Restoration advocates believed that once absolute power was restored to the emperor, he would, as the benevolent father of his people, undertake the necessary social reforms, beginning with land reform, to relieve the poverty of his sekishi (children).

If Restoration advocates were in general agreement about their ultimate goals, there were many details, large and small, that remained unclear, sometimes deliberately so. First, how exactly was a Shōwa Restoration to come about? Would simple assassinations of allegedly corrupt political, business and court figures be sufficient? If so, how many? Would a military coup, with or without street riots, leading to the proclamation of martial law, also be necessary? If so, should the coup be staged, at least initially, in the absence of the emperor’s knowledge and approval? What should happen in the event Emperor Hirohito were opposed to the coup or refused to enact the necessary social and economic reforms deemed necessary to relieve the suffering of his subjects?

Added to this was the whole question of whether it was right for the emperor’s subjects to even harbor expectations, let alone make demands, of their divine emperor. And if demands were made, what, specifically, should their content be? In the event the emperor refused to enact the desired reforms, might he be replaced by another member of the Imperial family, e.g. his younger brother Prince Chichibu (1902-1953) who was regarded as more amenable to the desired reforms? All of these questions and more were the subject of ongoing discussions among the various military and civilian advocates of the Shōwa Restoration. In the end, no consensus was ever reached, other than their belief in the need to take decisive action as soon as possible.

Was this lack of consensus, I wondered, connected in some way to the lenient treatment Inoue received following his arrest in the aftermath of the terrorist acts of his followers? Or, alternatively, was it connected to the harsh measures taken against the coup-related young officers and their civilian ideologue, Kita Ikki (1883-1937)? Or could this lack of consensus even be the key to unlock the disparity in treatment meted out to the perpetrators of both incidents?

The Blood Oath Corps Incident

Before exploring this question further, let us briefly review the first of the two terrorist incidents involved, beginning with the earliest of the two, i.e. the Blood Oath Corps Incident of spring 1932. Born Inoue Shirō in Gumma Prefecture in 1886, Inoue spent his young adult life as a drifter and adventurer, eventually going to Manchuria and northeast China where he proved his loyalty to Imperial Japan as a spy for the Japanese army. After returning to Japan, Inoue began an intensive period of spiritual training on his own and claimed to have had a Zen Buddhist-related enlightenment experience in 1924. After that, he went to Ryūtakuji temple in Shizuoka Prefecture to undergo traditional “post-enlightenment” (gogo) training under the guidance of Rinzai Zen Master Yamamoto Gempō (1866-1961).

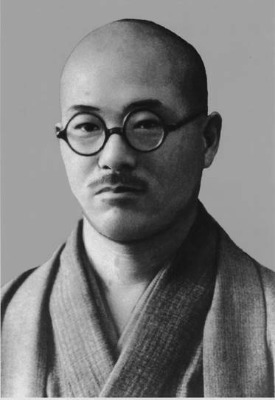

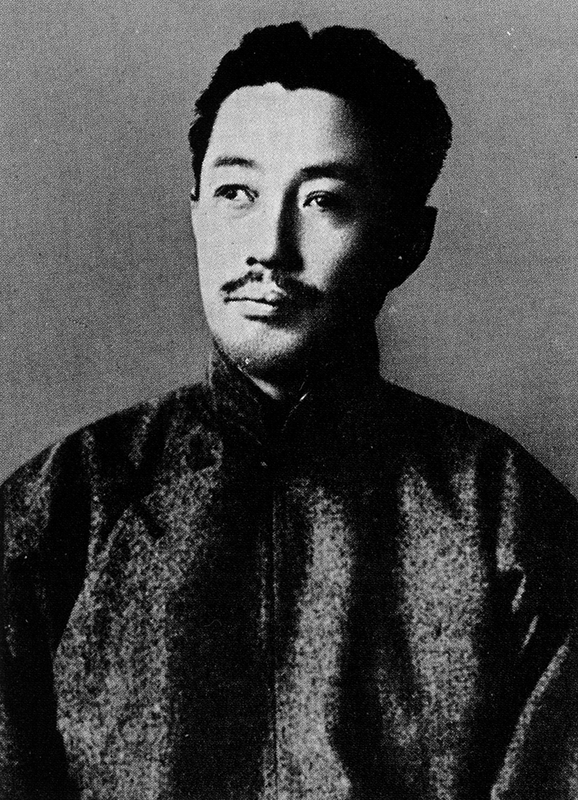

Inoue Nisshō

In 1927, while in the midst of his training, Inoue was invited by Count Tanaka Mitsuaki (1843-1939) to serve as the abbot of a newly built temple in the seaside village of Ōarai in Ibaraki Prefecture named Risshō Gokokudō (Temple to Protect the Nation through the Establishment of the True Dharma). Tanaka remained an influential court advisor even after service as Emperor Meiji’s Imperial Household Minister from 1898 to 1909. Because the temple in question had just been constructed, it was not yet affiliated with any sect, making it possible for Inoue to serve as the temple’s abbot even though, as no more than a Zen-trained layman, he was unqualified to do so. For his part, Inoue accepted this position because he believed Japan required radical social transformation and intended to use the temple as a training center to promote social reform among radicalized youth. By this time, he had changed his personal name to Nisshō (“Called by the Sun”).

In the aftermath of the failure of a coup d’état by rightwing Army officers affiliated with the Sakurakai (Cherry Blossom Association) in October 1931, Inoue became convinced that national reform could only be achieved through a violent confrontation with what he saw as the forces of evil: politicians, many of whom advocated cooperation with the West; wealthy zaibatsu corporate leaders; and corrupt members of the emperor’s court circle in league with the former groups. He decided to employ the tactic of “ichinin issatsu” (one person [kills] one) and drew up a list of twenty politicians, business leaders and court members whose assassination would be the first step toward restoring supreme political power to the emperor, i.e. the Shōwa Restoration.

Inoue’s band also included rightwing young officers in the Imperial Japanese Navy who, among other things, strongly objected to the discriminatory arms limitations imposed on Japan by the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. Later, a group of right-wing university students in Tokyo would also join. Inoue distributed Browning automatic pistols to his bandmembers; however, only two succeeded in carrying out their assignments before the plot was discovered and the remaining band members, Inoue included, were arrested.

Assassinations

On 9 February 1932, band member Onuma Shō (1911–1978) shot former Minister of Finance, banker and politician, Inoue Junnosuke (1869-1932), as he stepped from his car at the Komamoto Elementary School in Tokyo where he was to give an election speech. On the morning of 5 March 1932, a second band member, Hishinuma Gorō, waited outside the entrance to Mitsui Bank in Nihonbashi, Tokyo. When Dan Takuma, Director-General of the Mitsui zaibatsu, arrived by car, Hishinuma shot him dead on the spot. Neither killer sought to flee, and both were immediately apprehended. Inoue, aware the police were watching him, turned himself in on 11 March 1932 where he was not only treated with respect but even feted to a sake party that evening.

Inoue Junnosuke Dan Takuma

Two months later, in the 15 May Incident of 1932, a group of mostly young Japanese naval officers and cadets assassinated Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi (1855-1932) while his house guest, Charlie Chaplin, narrowly escaped assassination. Newly arrived in Japan, Chaplin had opted to see a Sumo wrestling match on the day of the assassination. The officers had hoped to sour relations between the US and Japan by assassinating Chaplin.

Inukai Tsuyoshi

Although, Japanese history books list the two incidents described here separately, they were in fact two stages of one operation. As Inoue explained: “Inasmuch as we [in the first wave of assassinations] were prepared for inevitable defeat, the best plan was to hold our naval members in reserve, waiting for the right time for them to form a joint force composed of both army and navy comrades who would then launch a second wave.”1

Note

The phrase “Blood Oath Corps” is actually something of a misnomer, for there is no evidence that Inoue’s band members took a “blood oath” in any literal sense. Instead, the term “Blood Oath Corps” (Ketsumeidan) appeared in the popular press during the group’s trial and was adopted by the lead prosecutor.

The 26 February 1936 Incident

The 26 February Incident (Ni Ni-Roku Jiken) was an attempted military coup d’état, commencing early on the morning of 26 February 1936. It was led by a group of young Imperial Japanese Army officers whose goal, once again, was the establishment of conditions leading to the Shōwa Restoration. Following the assassination of corrupt political and business leaders, together with their allies in court circles, and with the support of sympathetic senior military leaders, they anticipated martial law would be established, facilitating the implementation of the major domestic reforms they sought. Although the rebels succeeded in assassinating several leading officials (including two former prime ministers) and in occupying the government center of Tokyo, they failed in their attempt to assassinate Prime Minister Okada Keisuke (1868-1952) or secure control of the Imperial Palace.

26 February Incident

Initially, the supporters of the young officers in the upper echelons of the army attempted to capitalize on their actions. Leaders of the radical Imperial Way faction (Kōdō-ha) within the army, centered on Imperial Army Generals Mazaki Jinzaburō (1876-1956) and Araki Sadao (1877-1966), were sympathetic. The leaders of the more conservative and rival Control faction (Tōsei-ha) were not. The deciding factor, however, was Emperor Hirohito’s vehement opposition to the coup, ensuring its failure. The emperor gave direct orders to the military, including elements of the Imperial Navy, to move against the rebel officers, and in the face of overwhelming opposition, they surrendered on 29 February although two of them committed suicide.

It is important to note that unlike earlier examples of rightwing political violence conducted by members of both the military and civilians, this time the coup attempt had severe consequences. After a series of brief, closed trials, the Uprising’s 17 surviving officers, plus 2 civilian supporters, were found guilty of rebellion and executed. A further 43 Non-commissioned officers, 3 lower-ranking soldiers and 8 civilian accomplices were sentenced to prison terms of various lengths, up to life imprisonment.

General Mazaki Jinzaburō was the only high-ranking officer to be charged. Although his own testimony revealed he had collaborated with the young officers, he was found not guilty on 25 September 1937. This verdict has been attributed to the influence of Konoe Fumimaro who had become prime minister in June of that year.2 Nevertheless, Mazaki and Araki, along with other Imperial Way faction generals and lower ranking officers were either dismissed from active army service or sent to positions away from the capital where they would be less able to influence policy. The Imperial Way faction lost its influence within the army and the era of ‘government by assassination’ came to a close. At the same time, the military, that is to say, the Control Faction, increased its influence within the civilian government.

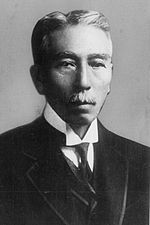

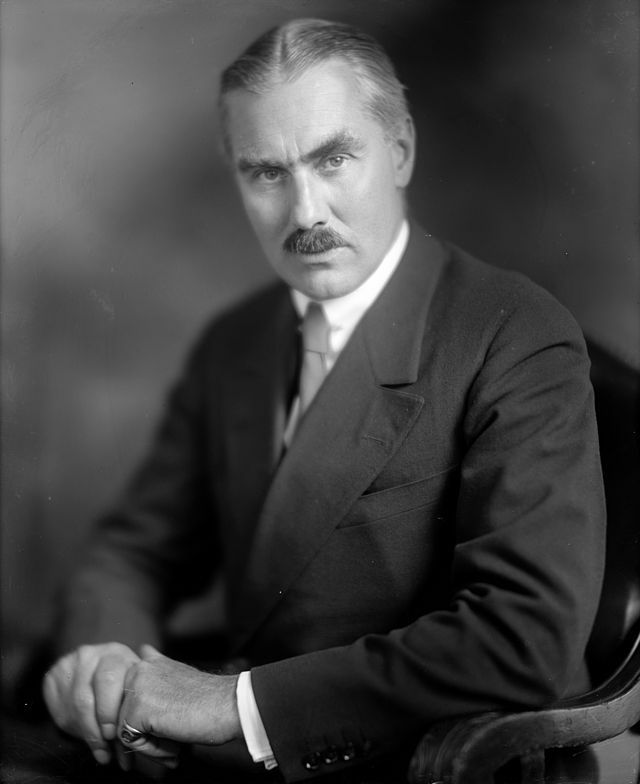

Konoe Fumimaro

Similarities

The first and most important similarity between the two incidents was, as previously mentioned, their shared dedication to the establishment of the Shōwa Restoration. Second, of course, was their willingness to employ violence, in the form of multiple assassinations of political and business leaders, as well as court officials, to bring the Restoration about. A third factor was their shared belief that Emperor Hirohito, once he enjoyed full political power, would undertake the necessary domestic reforms, especially land reform, in order to alleviate the pervasive poverty of the rural population. A heretofore unknown fourth factor was the incorporation of Zen training, especially the practice of Zen meditation, i.e. zazen, as part of the program of developing the resolute martial spirit necessary to employ terrorist violence coupled with the Buddhist-inspired willingness to sacrifice oneself in the process.

Inasmuch as I have explored the fourth factor elsewhere I will not repeat that here. Readers interested in this topic are invited to read “Is Zen a Terrorist Religion?” in the November 2021 issue of the Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies.3

Differences

It is the differences between these two incidents that, as mentioned above, provide the most striking contrast between the treatment meted out to the participants in the two incidents. While we know what happened to the young officers and associates, i.e. their closed trial and execution by firing squad, Inoue’s treatment was a series of polar opposites, starting from the very beginning of his terrorist activities. As a first step in understanding Inoue’s lenient treatment, let us examine some of the powerful figures he was close to.

Count Tanaka Mitsuaki

First, Inoue was invited to accept the abbotship of Risshō Gokokudō temple by Count Tanaka Mitsuaki who, albeit in his eighties at the time, remained closely connected to Emperor Hirohito. In fact, he was so closely connected that he took on a task of the most intimate nature, i.e. the selection of a suitable concubine for the emperor inasmuch as Empress Nagako had failed to give birth to a male heir, bearing four daughters instead. Fortunately, the empress gave birth to a son (Prince Akihito) on her fifth try in December 1933 and thus Tanaka’s efforts proved unnecessary. Nevertheless, Tanaka enjoyed a close relationship with Hirohito just as he had with both Hirohito’s father and grandfather, Emperors Taishō and Meiji.

Tanaka Mitsuaki

Of greater importance, in terms of his connection to Inoue, is that when the two men met in April 1927, Tanaka shared his dedication to eradicating the corruption he saw in the political parties and zaibatsu financial leaders of the day. Tanaka’s opposition was so strong he remained able, he claimed, “to cut down three to five men” of those he held responsible. That someone so close to successive Japanese emperors, including Emperor Hirohito, was personally willing to kill those he deemed corrupt suggests the importance Tanaka placed on Inoue’s mission.4 Although the question cannot be answered definitively, this raises the issue of whether, in seeking Inoue’s aid, Tanaka was acting entirely on his own or in league with powerful actors in the imperial institution?

Next, it should be noted that the newly constructed temple Inoue would head was built with the financial support of Tanaka in the first instance but, as temple records indicate, also from scores of Japan’s top political and military leaders, including Prime Minister Konoe Fumimarō (1891–1945). From its outset, the temple was promoted as the “foundation for reform of the state” through its training of Japanese youth. Its location immediately adjacent to a memorial hall to Emperor Meiji, also constructed by Tanaka Mitsuaki, only served to reinforce its patriotic nature. In short, the temple was constructed with a very specific patriotic purpose in mind by some of Japan’s top leaders.

Inoue’s Temple

The ”Voice of Heaven”

Second, at critical turning points in his life, Inoue claimed to have received directions from a mysterious source he referred to as the “voice of heaven.” For example, in July 1924 the voice of heaven told him to “travel to the southeast on 5 September.”5 Might the “voice of Heaven” have been preparing Inoue to undertake his role as a terrorist leader? This is just one of many unsolved mysteries whose answers we may never know. What is clear, however, is that whether in the person of Count Tanaka or Prime Minister Konoe Fumimarō Inoue enjoyed connections to powerful and influential men from the outset of his mission to effect radical change in Japanese society.

General Araki Sadao

Inoue first met General Araki Sadao in December 1930 at which time Inoue openly discussed the combined plans of the young military officers and civilians, including his band, to launch a major uprising to reform Japan. Araki not only indicated his support for their plan but added that once he heard the uprising had occurred, he would, as then commander of the Sixth Army Division in Kyūshū, lead his troops to Tokyo to ensure its success. Subsequently, it was General Araki who arranged for a military police escort for Inoue when he surrendered to the police on 11 March 1932. According to Inoue, the military police escort was necessary to ensure that he would not be humiliated by being arrested as a criminal on his way to turn himself in.6

Araki Sadao

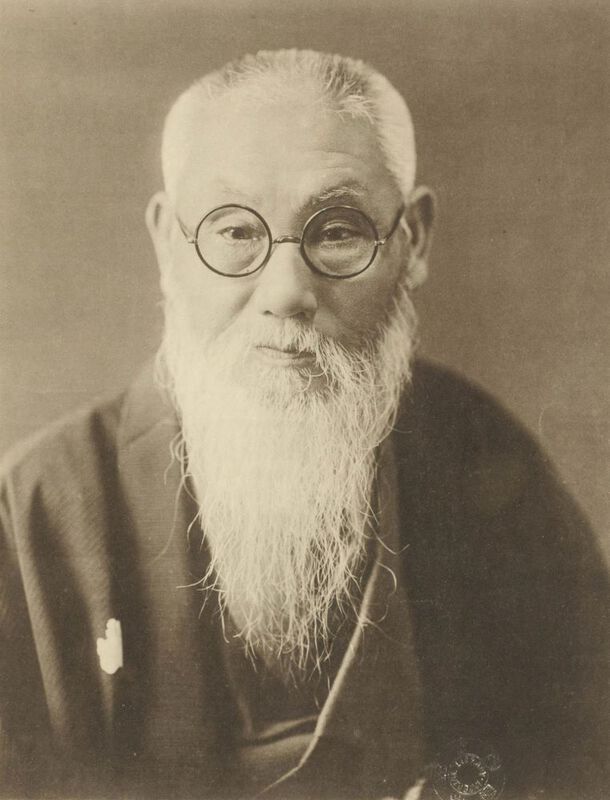

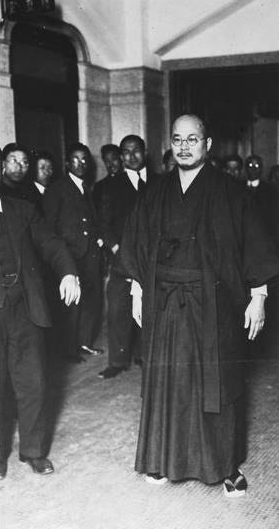

Tōyama Mitsuru

Not all of Inoue’s powerful patrons enjoyed reputations as sterling as those above. Chief among the latter was Tōyama Mitsuru (1855-1944), Japan’s ultimate “fixer” (kuromaku), who was equally at home with the crème of Japan’s ruling class as well as the country’s gangsters (yakuza). Unlike in his younger days as a founder of the Dark Ocean Society (Gen’yōsha) in 1881, by the 1930s, if not before, Tōyama seldom had to employ violence to shape events to his liking. For example, in 1920, Tōyama mobilized ultra-rightwing leaders to ensure (through the use of intimidation) that then Crown Prince Hirohito would be able to marry the woman of his choice, Princess Nagako Kuni (1903–2000), despite a history of color blindness in the princess’s family. This resulted in a lifelong relationship between Tōyama and the imperial court. Nakano Masao notes Tōyama grew so powerful that “when a new prime minister formed his cabinet, it was first necessary to secure Tōyama’s approval of those he appointed.”7

Tōyama Mitsuru

Inoue had first met Tōyama when he made a short visit to Japan while still a spy for the Imperial Army in China. It was Tōyama who, in 1921, had first suggested to Count Tanaka that Inoue might be of use to him. More importantly, once the assassinations carried out by the Blood Oath Corps began, it was Tōyama who hid Inoue from the police in a second-floor room above his son’s nearby martial arts hall. It was also Tōyama who, almost unbelievably, told Inoue’s father to inform his imprisoned son: “Tell Inoue he only has to serve three years.”8 This is despite the fact that Inoue had just been sentenced to life imprisonment. How could Tōyama have possibly known this in advance?

Yasuoka Masahiro

A fourth figure who possessed both a dark and bright side was Yasuoka Masahiro (1898-1983), head of Kinkei Gakuin (Golden Pheasant Academy), located on the grounds of the Tokyo residence of Yasuoka’s primary patron Count Sakai Tadamasa (1893–1971). Yasuoka offered Inoue a place to stay upon his arrival in Tokyo from Ōarai, and at least two members of Inoue’s band, both of whom joined in Tokyo, were originally Yasuoka’s students. It is not surprising the two men were attracted to each other inasmuch as Yasuoka was an influential rightwing backroom power broker whose lectures emphasized Confucian-inspired filial piety and loyalty to the emperor. Yasuoka attracted young government officials and army officers to his school, encouraging them to join the movement for the reformation of Japan.

However, despite the fact that Inoue and Yasuoka shared similar goals, their relationship was not a happy one. According to Inoue, Yasuoka aroused his students with stories of daring feats by past rebels in Japanese history but never went beyond talking about the past, never proposed a concrete plan of action to affect social reform. On the other hand, Inoue’s talks were the opposite and became so popular that students stopped attending Yasuoka’s lectures and came to meet Inoue instead. Yasuoka was so disturbed by this that he pressured Inoue to leave the school though not without first finding him a new place to live.

At the same time it is important to understand that in addition to harboring terrorists like Inoue, Yasuoka was intimately connected to the Imperial court. So well connected that he assisted in the formulation of Hirohito’s famous radio speech, i.e. the gyokuon hōsō (jeweled-voice broadcast), announcing Japan’s surrender on 15 August 1945. In appraising Yasuoka’s role, Roger Brown noted: “He [Yasuoka] employed classical language to cast Hirohito as the benevolent ruler of Confucian lore intervening to restore a peaceful and harmonious realm in accord with the Kingly Way (ōdō).”9

Thus we find Yasuoka, who once harbored a terrorist like Inoue, serving Emperor Hirohito by assisting him to announce, as eloquently as possible, Japan’s surrender. As if this weren’t sufficiently incongruous, Inoue writes that it was Yasuoka who informed police that he and his band were responsible for the assassinations of Inoue Junnosuke and Dan Takuma. This indicates that Yasuoka had been aware, at least to some degree, of Inoue’s plans. If so, why had he waited for two assassinations to take place before informing the police? And why wasn’t Yasuoka questioned about the possibility that he had abetted Inoue and his band’s terrorist acts?

Other Important Figures

In addition to the above, there are at least three additional figures who walked on the dark side in terms of their connection to ultra-rightist violence even while retaining close connections to some of Japan’s most powerful leaders, up to and including the emperor. These men were Ōkawa Shūmei (1886-1957), Marquis Tokugawa Yoshichika (1886-1976) and Kita Ikki. While Kita’s role will be detailed in the following section, Ōkawa was one of the most influential and long lasting of Japan’s ultranationalist writers and activists. He also played an important role in Inoue’s own actions including participation in the 15 May 1932 assassination of Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi, resulting in a five year prison sentence.10

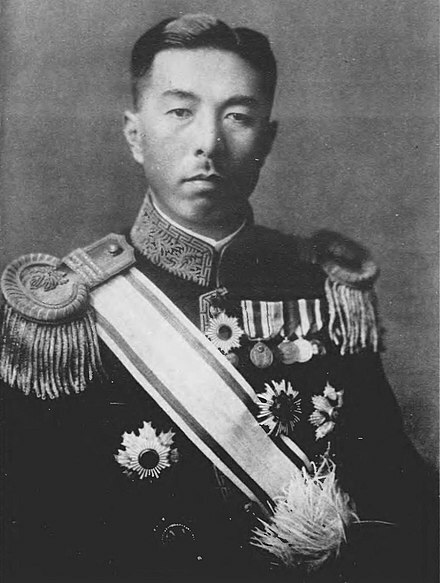

As an aristocrat, Tokugawa Yoshichika was a member of the Diet’s House of Peers. A botanist by training, he was granted the opportunity to meet Emperor Hirohito, also a botanist, at any time the latter was in his palace laboratory. Yet, at the same time, he was a major financial supporter of ultra-rightists from the 1920s onwards, especially in the 1930s. For example, Yoshichika donated what was then a large sum of money, somewhere between two hundred thousand and five hundred thousand yen, in support of an ultimately unsuccessful military coup set for March 1931. However, thanks to his position, he was never charged for his involvement nor was he ever questioned about his known contact with Inoue. Once again, we are left to speculate why an aristocratic politician, with ready access to the emperor, would finance ultra-rightwing militants?

Tokugawa Yoshichika

Major Surprising Events

Having looked at some of the powerful men Inoue was connected to, let us examine the major, documented events that can only be described as surprising if not, at times, astonishing. In the interest of brevity they are introduced in bullet form.

- In addition to being respectfully and treated to a sake party on surrendering to the police, Inoue successfully lobbied to have the chief judge at his trial, Sakamaki Teiichirō, removed because he refused to allow Inoue and his band members to testify about the patriotic motives for their acts.

- When the trial resumed, the new chief judge, Fujii Goichirō, not only allowed all defendants to testify at length about their personal backgrounds and motives, but also allowed them to appear in court in their formal kimonos, not prison uniforms, in a sign of respect.

- None of the band members, neither Inoue nor the two actual assassins, were sentenced to death.

- During his imprisonment, Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro intervened on Inoue’s behalf, requesting the emperor to shorten his life sentence.

- Inoue was granted a one-day parole in order to attend his father’s funeral who died on 12 April 1936. According to Inoue, this was the first time in modern Japanese penal history such permission had been granted.11

- While in prison, Inoue provided various services to prison officials, including determining the sincerity of those leftwing political prisoners who claimed to have undergone an ideological conversion. This conversion, known as tenkō (change in direction), was sometimes sincere, but sometimes faked in hopes of gaining release from prison. In return for his services, Inoue was given free run of the prison.

- As previously mentioned, shortly after Inoue received a life sentence, Tōyama Mitsuru told Inoue’s father to inform his son that although he had been sentenced to life, he would be released from prison after serving only three years. While Inoue wasn’t released after three years as promised, Inoue explained this was due to the Young Officers’ Uprising of 26 February 1936. That is to say, it would have been unseemly, to put it mildly, to release Inoue from prison while at the same time executing the young officers, for the latter proclaimed the assassinations they carried out were on behalf of a Shōwa Restoration. One key question is, how was it possible, at least initially, for Tōyama to have known Inoue would be released after serving only three years in prison?12

- Despite his failure to be released in only three years, Inoue’s sentence was progressively shortened by imperial degree until, in 1940, he and all of his band members were released from prison. Inoue was not only released from prison, but given a special pardon (toku-onsha) whereby his entire conviction was wiped clean. He could, of course, have been given a simple pardon but someone in a powerful position wanted to completely eliminate his criminal record.

- Within six months of release, thanks to arrangements made by Tōyama Mitsuru, Inoue, former head of a terrorist band, was hired by Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro to live on his estate as a confidant and advisor. The two men engaged in conversation from 11 pm to 1 am on a nightly basis.

- In their private conversations, both Inoue and Konoe recognized, even prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor, that Japan would lose a war with the US because that country was so much more powerful than Japan. As a result, from the beginning of the war they started planning and organizing for a defeated, postwar Japan.

- Although Inoue was initially accused by Allied Occupation investigators of having started the war, he was exonerated after lengthy questioning and never arrested nor indicted. He was, however, legally prohibited from taking part in public affairs during the Occupation.

- Following the end of the Occupation in 1952, Inoue once again resumed his rightwing activities as the head of a new ultra-rightest organization known as the Gokokudan (National Defense Corps).

Early Attempts to Make Sense of It All

Let me emphasize that I am not the first to try to make sense, or explain, the anomalies identified above. Attempts have been made to explain one or another of these surprising developments and at least one attempt has sought to explain the mild treatment afforded to the perpetrators of rightwing violence, at least up to the Young Officers’ Uprising of 1936. One example of an explanation for a single event relates to Inoue’s employment as a live-in consultant to Prime Minister Konoe Fumimaro, a development which, at first glance, certainly seems to be ‘one of a kind’. Where is there another example of a country’s leader hiring the head of a band of terrorists as his advisor?

A Partial Explanation

According to an entry in the diary of Vice Minister of the Navy Admiral Sayamoto Yorio (1886–1965), by 1940 Konoe was living under threats to his life made by various ultranationalists who feared the prime minister might make too many concessions to the United States during negotiations to avoid war. The admiral claimed this was the reason Konoe sought to employ Inoue. As an ultranationalist with a peerless reputation, Inoue would make an excellent bodyguard, for who would dare attack Inoue in an attempt to kill Konoe?

Although in his memoirs, Inoue himself made no reference to this possibility, it is certainly a plausible explanation, for we know that Inoue described a series of meetings he arranged to promote understanding between Konoe and ultranationalist leaders like Tōyama Mitsuru. Nevertheless, Inoue’s protection, if that’s what it was, was limited, for on 18 September 1941 four men, armed with daggers and short swords, jumped on the running boards of Konoe’s car as it left his private residence. They attempted to enter the car, but the car doors were locked. Before they had time to smash the car windows, they were apprehended by Konoe’s plainclothes police bodyguards.

An Overall Explanation

Japan historian Danny Orbach offers an overall explanation for why the Japanese legal system in the 1930s was, as a whole, so friendly to ultra-rightwing offenders, even when they assassinated leading statesmen and generals. In an article entitled, “Pure Spirits: Imperial Japanese Justice and Right-Wing Terrorists, 1878–1936,” Orbach reached the following conclusion:

The answer is intertwined with a cultural narrative defined here as “subjectivism,” that assigned vital importance to a criminal’s subjective state of mind when evaluating his or her transgressions. Though influenced by Western thought, this narrative was indigenous to Japan. It originated in the late Edo Period, shortly prior to the establishment of the Meiji State in 1868, under specific historical circumstances and was later reinforced by the policy of the early Meiji State.

Consequently, it pervaded education, politics and popular discourse alike, in the civilian sphere and even more so in the army. Until the early 1920s, this trend had a relatively modest influence on the Japanese justice system. It then began to gain traction in military courts dealing with political crimes of army personnel. From 1932 it influenced civilian courts as well, though civilian judges were relatively more reluctant to accept it than their military peers. After a peak in the mid-1930s, it again receded into the background, following the abortive coup d’état of February 26, 1936.13

Orbach alleged that the origin of this subjectivism could be traced back to a group of revolutionary samurai who fought against the Tokugawa Shogunate during the 1860s. Many of them were known as shishi (warriors of high aspiration) who began their careers as terrorists who attacked foreigners and Shogunate officials under the slogan Sonnō Jōi (Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians). Coming from lower ranking samurai families, they were angered by the worsening living conditions of their class and by a series of economic crises that hit the country in the nineteenth century. At the same time, influenced by the ideology of “national learning” (kokugaku), they looked to the emperor in Kyoto, not the Shogunate, as the rightful ruler of Japan.

These lower ranking samurai went on to become national leaders after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, placing emphasis on the subjective state of mind of an individual above and beyond the consequences of his or her actions. According to this ideology of subjectivism, the ideal state of mind of a shishi included: 1) spontaneity, 2) sincerity and, most importantly, pure motives. Thus, a pure-hearted shishi was not only spontaneous and sincere, but fought for the country and the emperor, not for personal or group gain. Once this impression had been created it became possible to commit acts of folly or even madness, for these were regarded as indications of a shishi’s sincere readiness to sacrifice his life.

Orbach also touched on related explanations given by John D. Person. Unlike Orbach, Person pointed to much later developments as the cause of leniency toward rightwing violence. Person first noted the failure of various Japanese law enforcement agencies to coordinate with one another. Second, Person pointed out that the state found it difficult to deal with rightwing nationalism because it was a radicalized version of official state ideology. A third observer, Wagatsuma Sakae, focused on the difficulty of punishing transgressors who expressed loyalty to the emperor in that law enforcers felt more committed to the emperor than to the letter of the law.

Returning to Orbach’s explanation, there can be no question that subjectivism as he defined it was a powerful force from the late Edo period onwards. But if one asks who was the chief beneficiary of this force it was clearly the emperor and those close to him. Thus, the question must be asked, were successive emperors, from Emperor Meiji onwards, no more than interested onlookers who played no role in shaping the events that took place in their name? While it is difficult to point to an incident or time when Emperor Meiji or his successors actively intervened to promote or enhance subjectivism per se, it is possible to point to an incident in which an emperor, i.e. Hirohito, actively intervened to show his resolute opposition to the actions of those who claimed to act on his behalf, namely, the young officers who led the uprising of 26 February 1936.

Thus, the question must be asked, at least in this instance, is it possible that Emperor Hirohito and/or those close to him may have intervened in further ways we don’t yet know about? Was it no more than subjectivism that led Count Tanaka Mitsuaki to invite Inoue to head a new temple, built with the funds of political and military leaders, that was dedicated to creating a band of youth possessing a “do or die spirit”? Was it no more than subjectivism that allowed Tōyama Mitsuru to tell Inoue’s father that his son would be released from a life sentence in prison in only three years? Or arrange for Inoue’s entire criminal conviction to be expunged from the record when he was released?

I trust I am not alone in thinking that something else must have been going on in the background. This something, or someone(s), were clearly more powerful than subjectivism alone despite the important contribution subjectivism made to the lenient treatment afforded perpetrators of rightwing violence, at least perpetrators up to the Young Officers’ Uprising of 1936. But what, or who, might that something or someone(s) be?

My Explanation

Before examining Inoue’s circumstances, let us begin with a closer examination of Emperor Hirohito’s role in the Young Officers’ Uprising, for all observers agree it was the emperor’s fierce opposition to the Uprising that resulted in its failure. Yet, why had Hirohito directly intervened in a movement that, at least in name, was undertaken as part of a Shōwa Restoration, the avowed goal of which was to restore him to a position of absolute power?

Herbert Bix explains that with three senior statesmen and ministers assassinated, and Prime Minister Okada Keisuke believed, albeit mistakenly, to have also been assassinated, “from the moment Hirohito learned what had happened, he resolved to suppress the coup, angered at the killing of his ministers.” Apropos of this, an angry Hirohito stated, “By cutting down all the ministers on whom I rely on the most they are trying to slowly destroy me. If the army hesitates [to act], I will personally lead the Imperial Guard Divisions to crush the rebel forces!”

Bix adds another significant bit of information when he notes, “[Hirohito] also feared that the rebels might enlist his brother, Prince Chichibu, in forcing him to abdicate.”14 Bix further notes that Hirohito’s relations with his brother “were not always amicable.”15 In point of fact, the relationship between the two men was very tense, leading to a number of acrimonious exchanges between them. One of the most acrimonious, quoted here in its entirety, occurred at the end of 1931 in the aftermath of two failed military coup attempts in March and October of that year.

Prince Chichibu

Chichibu: I think it’s necessary to have a government administered directly by the emperor.

Hirohito: What do you mean by that? What is it you wish to say?

Chichibu: If necessary, I respectfully request the [Meiji] constitution be suspended. Under the banner of a government administered directly by the emperor, I would like you to suspend the constitution, restrain the zaibatsu financial conglomerates, improve the lives of farmers, promote industry on behalf of workers, and improve the foundation of the lives of ordinary people.

Hirohito: Prince, where did you get all that? I never would have imagined a military man would suggest things like suspending the constitution. Aren’t you a member of the imperial family? You clearly know nothing about the duties of an imperial family member, let alone the responsibilities of an imperial soldier! You should ask yourself what your duty is, including the appropriateness of making suggestions about the constitution that Emperor Meiji established, protected, and nurtured.

Chichibu: Your Majesty, you speak about imperial soldiers, but their reality has no substance. The wretched condition of the soldiers and their families is beyond description. While serving in the military, their older and younger sisters end up being sold as barmaids and geisha. Is there any greater hypocrisy or deceit than asking soldiers who have experienced these hellish conditions to die for their country? Your Majesty, can you bear a deceitful situation like this? I can’t. I can’t bear it when I think of the genuine army soldiers who are prepared to give their lives for the Great Empire of Japan. I can’t bear it even if my body were to be cut up into eight, nine, or ten pieces!

Hirohito: I’m aware of this situation. It is the result of my lack of virtue. Truly, I have no words to express my regrets to the ancestors of the Imperial dynasty.

Chichibu: It’s not a question of Imperial ancestors! Instead, it’s a question about today’s soldiers and ordinary people. It’s a question of soldiers and citizens who are alive now, who sweat as they work, of soldiers who are prepared to shed their blood. It’s a question of men and women. Please make a firm decision. Please help them. The people of this country are awaiting your decision.

Hirohito: Prince, you talk about government administered directly by the emperor. However, according to the provisions of the constitution, I’m already in charge of making broad policies and presiding over their administration. What more do you want me to do?

Chichibu: . . . (frustrated, Chichibu bowed slightly and left the room).16

Commenting on this exchange, historian Fukuda Kazuya notes that Prince Chichibu was a captain in the Third Azabu Regiment stationed in Tokyo. The young officers in his unit were deeply influenced by the national socialist–oriented writings of Kita Ikki and formed the nucleus of the Young Officers’ Uprising. Through his contact with these officers, Chichibu had come to share their concerns as reflected in the requests he made of his older brother. However, beyond his expression of regret, Hirohito showed little sympathy for Chichibu’s requests.

In light of the above exchange, it is clear why Hirohito almost immediately expressed his disapproval of the Young Officers’ Uprising of 26 February 1936. That is to say, in addition to his opposition to the demands of the young officers for radical social change, Hirohito had ample reason to fear that a successful uprising would lead to his replacement by his younger brother. Summarizing the brothers’ quarrel, Fukuda writes:

The exchange between them was fierce. Never before in the history of the Imperial family since the Meiji Restoration had two influential members engaged in such a stormy debate. The intensity of the disagreement was the result of conflict over the state of the country and the path it should follow. At the same time it symbolized the divisions in public opinion and [the country’s] uncertain future.17

Kita Ikki

I suggest Prince Chichibu’s connection to national socialist Kita Ikki is the key to understanding not only Emperor Hirohito’s vehement opposition to the Young Officers’ Uprising but why the young officers were all shot in its aftermath, including Kita Ikki who was not a direct participant in the Uprising. Let us next examine Kita Ikki and his ideology.

Kita Ikki

Kita was born on Sado island in Niigata Prefecture in 1883. Due to its remote location in the Japan Sea, Sado was used as a place of exile up thru the 18th century and its modern day inhabitants still enjoyed a reputation for their rebellious spirit, something Kita took pride in. He was attracted to socialism from the age of fourteen because it combined moral ideals, like justice and freedom, with a scientific analysis of history. In 1900 he began publishing articles in the local newspaper including those critical of the Meiji state and questioning the nature and role of the emperor system. This resulted in a police investigation, but no charges were brought against him.

Kita’s major break with mainstream socialism came at the time of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5. Whereas mainstream socialism was strongly opposed to imperialist warfare, Kita chose to support Japan’s war effort. Thus, Kita opposed the anti-war stance of the Heimin Shinbun edited by Kōtoku Shūsui (1871-1911), one of socialism’s major proponents in Japan. This divergence can be said to mark the beginning of Kita’s adoption of an ideology best described as a variety of national socialism, i.e. advocating socialist reform at home even while supporting the expansion of the Japanese empire abroad. His national socialism also contained an element of blut und boden (blood and soil) in that he sought to create a Japanese brand of socialism that accommodated traditional values, emphasizing the common ground between Japan’s “national essence” (kokutai) and socialism.

Kita’s national socialism should not, however, be confused with the national socialism of the Nazis. For one, the first of his major books on socialism, a massive 1,000-page political treatise entitled, The Theory of Japan’s National Polity and Pure Socialism (Kokutairon oyobi Junsui Shakai-shugi) was written in 1906. His second book, An Outline of the Plan for the Reorganization of Japan (Nihon Kaizō Hōan Taikō) was written in 1919 and published as a book in Japan in 1923. Thus, both books predate the 1925 publication of Mein Kampf in which Hitler outlined his political ideology and future plans for Germany.

Secondly, in reality Hitler’s commitment to socialism, either at home or abroad, was little more than a front for his deep connections to Germany’s capitalist leaders who secretly funded the Nazi movement as a means of preventing a leftwing revolution. These leaders were well aware that Hitler’s “socialism” was little more than a lure to gain the support of Germany’s working class. They also understood that Hitler despised traditional socialism because of its international working-class solidarity, opposition to capitalism, and inspiration it found in the writings of Karl Marx, a Jew. For Hitler, traditional socialism was no more than a Jewish ideology designed to enslave or even destroy the Germans as a race composed of pure “Aryans.”

By contrast, domestically at least, Kita advocated genuine socialist reforms even though they were neither fully democratic nor pacifistic. For example, Kita demanded universal suffrage, though only for men. Women’s role was to bear children, and they should not be dragged into politics. As for workers, Kita proposed they be protected and given a fair share of the profits but, at the same time, not allowed to strike. Major industries were to be nationalized together with limits set on individual wealth, assets of companies and private property. Urban land would become municipal property and land reform would be undertaken in rural areas. This latter provision was designed to improve the lot of impoverished tenant farmers.

A unique feature of Kita’s ideology was his view of the role of the emperor. For Kita, the emperor was a symbol, the representative of the people. Kita ridiculed what was then the widely accepted idea of bansei ikkei, i.e. the existence of an eternal unbroken line of emperors in Japanese history. Thus, he dismissed the claim that the Imperial family was in any way unique and rejected the concept that Japan was a family state with the emperor as its father. In his view, the monarch was not of divine descent and the people of Japan did not belong to him. On the contrary, the people came first and he was therefore the people’s emperor.

In short, Kita had no use for the old-style monarchy and called for not only the abolition of the nobility but the nationalization of the emperor’s property. The emperor would henceforth receive a stipend from the state in return for his services to the Japanese people, services, however, that would be covertly reduced. Although the emperor was slated to become a figurehead for political and religious use under the military’s control, Kita recognized that for the major reforms he advocated to be successful they would need to be implemented, following a coup, by a strong leader under a state of martial law. In light of the Japanese people’s history, he felt the emperor was best suited for this purpose.

Finally, with post-reform Japan strengthened internally, the country would be able to embark on a crusade to free all of Asia from Western imperialism. Kita justified Japan’s actions, saying: “Britain, astride the whole world, is like a very rich man, and Russia is landlord of half the northern world. Doesn’t Japan, which is like a propertyless person in international society, confined to these small islands, have the right to go to war to overthrow their domination in the name of justice?”18

As Asia’s first modern nation, Kita believed Japan had the responsibility to liberate other Asian nations as well as ensure the livelihood of its own people. Thus, when Kita called upon Japan to seize Manchuria he did not regard it as an act of aggression but, on the contrary, it was to be done to protect China from Russian encroachments. At the same time Manchuria’s broad expanses would provide a place to settle impoverished, landless farmers from the home islands. To make this possible, the military would be further strengthened so as to not only control Manchuria but further, to conquer Siberia in Russia’s Far East and even Australia.

The Japanese empire proper was destined to consist of Korea, Taiwan, Sakhalin and Manchuria though the incorporated peoples were to be granted the same rights as Japanese citizens. This was predicated on Kita’s belief that without the equitable resolution of issues related to international distribution, Japan’s internal social divisions could not be overcome. Further, Japan’s self-appointed role as the champion of Asian unity required it to support India’s struggle for independence as well as end the partition of China by Western powers. Thus, even while advocating Japan partition China by taking over Manchuria, Kita supported Japanese imperialist expansion “in the name of justice.”

Prince Chichibu

In light of Kita’s proposals for major social reforms, it is easy to see why his nationalistic brand of socialism appealed to the young officers and served to inspire the abortive coup, especially as approximately half of the army’s officers came from rural backgrounds. What is surprising, however, is that Kita’s reforms were attractive to at least one member of the Imperial family, Prince Chichibu, Emperor Hirohito’s younger brother. Bix notes that Kita personally presented the Prince with a copy of An Outline of the Plan for the Reorganization of Japan in the early 1920s.19 In the following years, as a military commander of both young officers and recruits from impoverished rural areas, Chichibu became ever more aware of the need to improve what he described as “the wretched condition of the soldiers and their families.”

As the reader will recall, Prince Chichibu requested Hirohito create a government “administered directly by the emperor,” even if that required suspending the constitution. Chichibu’s requests echoed those made by Kita and demonstrate that Chichibu was well aware of, and sympathized with, Kita’s ideology. And, needless to say, it is difficult if not impossible to believe that Hirohito would have been unaware of the source of these requests and the implications they portended for drastic changes to Japanese society, let alone his position. At no time did Hirohito show an interest in enacting any of these changes.

It should now be crystal clear that the genuine anger Hirohito felt concerning the assassinations of his close advisors was multiplied many times over by the dire, if not existential, threat the Young Officers’ Uprising posed to his continued occupancy of the throne. Moreover, there are indications Hirohito knew in advance something was going to occur. Early on the morning of the coup, upon being awakened and informed of what was taking place, Hirohito said, “So [it] finally happened!” (Tōtō yatta ka).20 He immediately designated the young officers and their troops as a “rebel army” (zokugun), effectively sealing their fate from the outset.

One very interested outside observer of the coup was US Ambassador Joseph Grew who literally had a ringside seat on events as they unfolded. In his book, Ten Years in Japan, Grew wrote: “The rebels were situated in the official residence of the Prime Minister and the Sanno Hotel, very near us, and their banners floated from both buildings; we watched their movements through glasses from our [embassy] roof.”21 Despite the fact that Grew identified the young officers as the “Fascist element in the Army,” in the failed coup’s aftermath he made a very prescient observation: “One thing emerges as absolute certainty, there must be a ‘New Deal’ in Japan or the same thing will happen. . . again and again.”22

Joseph Grew

As Grew could not help of having been aware, the socialist-influenced “New Deal” reforms of which he spoke were never implemented in Japan due to the intransigence of one man, Emperor Hirohito. Yet, at the same time, the “same thing” (i.e. a military coup) never happened again. Why not? Because Hirohito made an example of the young officers, all of whom he had shot following a closed, perfunctory court martial shortly after their surrender including their civilian ideological mentor, Kita Ikki. To protect his throne in the midst of his unwillingness to support domestic socialist reforms, Hirohito needed to demonstrate the fate that awaited anyone sympathetic to the need for major social reform in Japan, especially those in the military.

Nevertheless, Grew’s comments were prescient, albeit ironic. Prescient because despite Hirohito’s adamant opposition, the major, socialist-tinged reforms of the New Deal were eventually implemented in Japan as he believed they should be. Ironic because these reforms, beginning with major land reform, were similar to those demanded by the young officers whom Grew had identified as the “Fascist element in the Army.” However, the reforms, when they came, were at the hands of General Douglas MacArthur (1880–1964) and the Allied Army of Occupation in postwar Japan. Were they enacted by a “Fascist element”?

The Wall Street Coup

In what can only be called a final irony, the architect of the New Deal, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) faced a ‘dire threat’ of this own, similar in some ways to that Hirohito faced. When FDR pushed for his socialist-tinged New Deal reforms in 1933, he so angered a group of influential, wealthy Americans that they prepared to oust him from the presidency, possibly even assassinate him. These wealthy Americans secretly planned for a military coup d’état to be led by retired US Marine Corps Maj Gen Smedley Butler. Butler, a two time winner of the Congressional Medal of Honor, was known as a soldier’s soldier and idolized by veterans. Famous for his daring exploits in China and Central America, Butler enjoyed an impeccable reputation.

Smedley Butler

Concretely, the proposed coup called for Butler to lead a massive army of 500,000 WW I era veterans – funded by $30m from Wall Street titans and weapons supplied by Remington Arms – to march on Washington, oust Roosevelt and establish a fascist dictatorship. Butler later referred to these men as “the royal family of financiers” whom he contended controlled America’s veterans by way of the American Legion, established in 1919. On December 8, 1933, Butler said, “I have never known one leader of the American Legion who had never sold them [military veterans] out—and I mean it.”23 For Butler, the Legion was a militaristic political force, notorious for its antisemitism and reactionary policies opposing labor unions and civil rights, dedicated to convincing veterans to support rightwing causes.

The coup might have succeeded had Butler not reported it to J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI, who then reported it to FDR. When a congressional inquiry was convened, Butler testified that in the summer of 1933 he had been approached by a bond-broker and American Legion member named Gerald MacGuire. MacGuire told him the coup was backed by a group called the American Liberty League, a group of business leaders formed in response to FDR’s 1933 election victory. Members included not only JP Morgan, Jr, and Irénée du Pont, but Robert Sterling Clark of the Singer sewing machine fortune, and the chief executives of General Motors, Birds Eye and General Foods.

Significantly, when the congressional committee’s final report was delivered in February 1935, it concluded: “[The committee] received evidence showing that certain persons had made an attempt to establish a fascist organization in this country,” adding “There is no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed it expedient.” The head of the congressional investigation, John McCormack wrote: “If General Butler had not been the patriot he was, and if they had been able to maintain secrecy, the plot certainly might very well have succeeded … When times are desperate and people are frustrated, anything could happen.”24

Butler was not happy with the congressional committee’s final report. He demanded to know why the names of the country’s richest men had been removed from the report. In a Philadelphia radio interview in 1935, Butler said, “Like most committees, it has slaughtered the little and allowed the big to escape. The big shots weren’t even called to testify. They were all mentioned in the testimony. Why was all mention of these names suppressed from this testimony?”25

Unlike Japan where the radical young officers were executed, together with disciplining their senior military supporters, in the US the “big shots” escaped punishment. In his radio program, “The White House Coup, 1933” the BBC’s Mike Thomson, in the wake of extensive research, reached the conclusion this was because FDR secretly struck a deal with the plotters, allowing them to avoid treason charges – and possible execution – in exchange for Wall Street backing off its opposition to New Deal legislation.26 As we have seen, Ambassador Grew recognized just how critical the New Deal domestic reforms were to pacifying demands for social and economic justice in the US when he wrote: “One thing emerges as absolute certainty, there must be a ‘New Deal’ in Japan or the same thing will happen. . . again and again.”

Needless to say, one of the main factors Hirohito and FDR shared in common was their determination to stay in office in the face of the dire threat each of them faced. Equally if not more important, however, was a second factor – their shared dedication to the continuation of the capitalist system at whatever cost. In light of the socialist-tinged New Deal reforms FDR embraced, it may seem incongruous to claim that FDR was, like Hirohito, dedicated to saving the capitalist system. That incongruity is explained, however, by the fact FDR maintained that in order to save capitalism from itself it would be necessary to “equalize the distribution of wealth.” In the course of doing this he was prepared to “throw to the wolves the forty-six men who are reported to have incomes in excess of one million dollars a year.”27 Thus, the real difference between FDR and Hirohito was how best to accomplish their common goal – saving capitalism.

In the Aftermath of the Attempted Coup

Despite his opposition to implementing New Deal-like reforms in Japan, there can be no doubt that Hirohito’s longstanding opposition to socialism of any kind made him an attractive figure to Grew who became one of the strongest advocates at war’s end for keeping Hirohito on the throne, including absolving him from all responsibility for the war. In short, Hirohito had proven he could be trusted to maintain Japan as a capitalist state while, at the same time, using the power and prestige he had left to oppose a resurgent left in postwar Japan. In the midst of the Cold (and Korean) War of the postwar era, Hirohito’s support was welcome indeed.

As for ordinary Japanese of the wartime era, all hope of major domestic reforms of any kind, including land reform within Japan proper, died together with the young officers and Kita Ikki. However, one proposed reform remained viable – the opportunity to emigrate to Manchuria, since 1932 known as Manchukuo, a puppet state of the Japanese empire. While the socialist elements of national socialism had been destroyed, the ‘national’ element, i.e. the imperialist element, was still very much alive and being implemented, this time with Hirohito’s approval.

An estimated 1.55 million to 2 million Japanese emigrated to Manchuria in an ill-fated mission to colonize Manchukuo. Of this number around 320,000 were impoverished tenant farmers lured to Manchuria by the promise of owning their own land, something they had little to no hope of acquiring in Japan proper. At the Imperial Army’s insistence, and with its aid, many of them were located in Manchuria’s northern reaches where their young men were trained as militia as part of the effort to block Russia’s southern expansion into China, just as Kita had proposed.

Nor should we forget to mention Prince Chichibu. In August 1935, Chichibu had been transferred to Hirosaki in the far north of the main island of Honshu where he served as a Captain in the 3rd Battalion of the 31st Infantry Regiment. While the reasons behind his reassignment to this distant outpost are contested, it is known that Hirohito was determined to separate his younger brother from the radical, reform-minded elements in the army, especially after learning that Chichibu had visited Kita Ikki at his home in the company of one of the radical officers. In any event, it proved fortuitous to Hirohito that the one man who was in a position to replace him was located a full day away from Tokyo by train.

Following the coup’s outbreak, Prince Takamatsu telephoned Chichibu to let him know what had happened. However, he didn’t immediately invite Chichibu to return to Tokyo until later in the day, concerned about how his presence might be interpreted. Thus, Chichibu didn’t board the train for the long trip back to Tokyo until the evening of the 26th, arriving in Tokyo on the afternoon of the 27th, still in the midst of the coup. Chichibu was taken directly to the Imperial Palace by car, on a route ensuring he would be unable to meet the rebellious troops. Along the way Chichibu received a briefing on the unfolding events from his younger brother, Prince Takamatsu. During his audience with the emperor, Chichibu apologized that a unit he had once commanded in Tokyo was part of the rebellion.28

Thus, while it appears Chichibu was not directly involved in the coup, there is a report that in its aftermath the relationship between the two brothers remained strained. Even two years later, in the spring of 1938, Prince Saionji Kinmochi (1849-1940), a senior elder statesman, revealed to his secretary that he feared sibling rivalry in the Imperial family could one day lead to murder. In this case Saionji was referring to both Chichibu and his younger brother, Prince Takamatsu (1905-87), who had come to share Chichibu’s thinking over the years.29

I note that my evaluation of the motives of the young officers involved in the coup is substantially different from that of Herbert Bix who writes:

Further, despite the rural roots and populist rhetoric of the ringleaders, most had not become revolutionaries because of the agricultural depression, and their ultimate goals had little to do with agrarian reforms, as many contemporaries imagined. The main aim of the insurgent leaders was to further the good of the kokutai [national polity], as they understood it, by accelerating Japan’s rearmament.30

Due to their rural background, relative low rank and concern for the impoverishment of landless farmers, I find the young officers were sincere in their support for the domestic socialist reforms Kita Ikki advocated. My evaluation is similar to that of German historian Gerhard Krebs who wrote: “The putschists’ [young officers] program was strongly influenced by his [Kita Ikki] and Nishida Mitsugi’s writings and therefore had a strong anti-capitalist and reformist orientation in favor of the underprivileged classes.”31

Nishida Mitsugi (1901-37) was a former army officer and Kita supporter who worked with him to spread his thought among young army officers. Nishida had been close friends with Chichibu since their time together as classmates at the Army Academy in the class of 1922. While at the Academy, Chichibu has asked for information about the plight of the distressed rural population. In response, Nishida promoted Kita’s ideas for social reform, hoping to reach the ear of the emperor through the prince. Even after graduation from the Academy, Chichibu and Nishida remained in contact and continued to correspond while the latter was studying in Oxford in 1925. Like Kita, Nishida was not directly involved in the Young Officers’ Uprising of 1936 but, nevertheless, was sentenced to death with Kita for the ideological influence the two of them exerted on the young officers.

Gerhard Krebs notes that Chichibu was also influenced by Imperial Way faction leader, General Araki Sadao, who was the head of the Army War College when Chichibu entered in 1928. Araki took a personal interest in the Prince’s military education, beginning with a directive that the Prince write an essay on the life and thought of the Japanese people. In response, Chichibu’s essay criticized the great difference between rich and poor and the selfish behavior of the wealthy. Additionally, Chichibu was influenced by Captain Andō Teruzō (1905-1936), one of the leaders of the 1936 coup, for Andō had earlier been Chichibu’s military science instructor at the Army Academy. 32

In light of this, the heated argument previously quoted between Chichibu and Hirohito is hardly surprising, for the Prince was clearly deeply influenced if not an outright advocate of the domestic socialist reforms they all embraced. Nor is it surprising that Chichibu became the idol of reform-minded and restless young officers. As we have seen, the prince was so unwilling to accept the social injustice then so widespread in Japan that he was prepared to act “even if my body were to be cut up into eight, nine, or ten pieces.” Krebs further notes that the national socialism they embraced was the real thing, writing that the young officers “drew their ideological – national socialist in the truest sense of the word – armor mainly from the extremist theorists Kita Ikki and Nishida Mitsugi.”33

In this connection I note that I don’t find advocacy of major social reform at home and rearmament for major imperialist aggression abroad to be contradictory, for they were actually the twin goals of national socialism. As for the “many contemporaries” Bix writes about who thought the young officers were dedicated to agrarian reform, that could also be said about those contemporary Japanese who, even today, continue to show their admiration for the sacrifice these young officers made. Among other things, this is revealed by the erection of the large memorial to the officers at the site of the former army prison in Tokyo’s Shibuya Ward where they were executed. It is not by accident that the central motif of this memorial is a large statue of Kannon Bodhisattva. Bodhisattvas are personages who willingly sacrifice themselves for the welfare of others and “Kannon” literally means someone who “hears the cries (of those who suffer).”

Young Officers Memorial

On a closing note, just before the young officers were shot, they shouted, Tennō Heika Banzai! (Long live the Emperor!), revealing they remained loyal subjects of the emperor to the end. However, Captain Andō Teruzō added, “Chichibu no Miya, Banzai!” (Long live Prince Chichibu!). For his part, the Prince is said to have long mourned the death of his friend.34

Inoue Nisshō and his Band of Terrorists

If we can now understand why the coup’s young officers and Kita Ikki had to be killed, we are still left without an explanation for the lenient, even supportive, treatment afforded Inoue and his band, especially when they, too, carried out assassinations of leading political and business leaders in the name of a Shōwa Restoration. What was the difference between them?

The short answer, politically speaking, is everything. To understand what this means let us first turn to the statement Inoue made at his trial when asked to explain the political ideology guiding his actions. Inoue testified, “I have no systematized ideas. I transcend reason and act completely upon intuition.”35

The distinguished political scientist, Maruyama Masao (1914-1996), used this statement to assert that Inoue “deliberately rejected any theory for constructive planning.”36 In Maruyama’s eyes, Inoue illustrated the putative immaturity and lack of modern subjectivity defining Japan’s ultra-rightists. Was he correct?

Inoue at his trial.

In order to better address this question, let us first examine a few additional relevant quotations, beginning with that of Onuma Shō, assassin of the former Minister of Finance Inoue Junnosuke. Onuma testified:

Our goal was not to harm others but to destroy ourselves. We had no thought of simply killing others while surviving ourselves. We intended to smash ourselves, thereby allowing others to cross over [to a new society] on top of our own bodies.

Hishinuma Gorō (1912–1990) was the assassin of Dan Takuma (1858-1932), the Director-General of Mitsui zaibatsu. When the judge asked Hishinuma about his plans for reforming the country, Hishinuma replied, “I didn’t think about construction at all, only destruction.”37

Yotsumoto Yoshitaka was a third member of Inoue’s band. His target was Makino Nobuaki (1861-1949), Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, but Yotsumoto was apprehended before he was able to strike. At his trial Yotsumoto testified:

The first thing Inoue taught us was to come and follow him, doing as he did. Inoue said various things about revolution, but the first was that it entails destruction. We shouldn’t say we can’t do this because it’s bad, or let’s wait and see what’ll happen. We are now in a situation where things have come to an impasse, so this is no time to talk about theory, only destruction. . . . This is why Master [Inoue] never talked to us about things like revolutionary theory or logic.38

An even more telling quote by Yotsumoto about the young officers’ attempted coup is the following:

There have been some young people of late who advocate the adoption of national socialism. However, when this ideology is examined, it is nothing but a left-wing fake, using left-wing terminology. These young people are attempting to get the masses to launch an insurrection. Further, they think things like Marxism or socialism will save society. Not only that, they attempt to attach the emperor or the national polity to this ideology, but I think this is a big mistake.39

As the last quote makes clear, there was an unbridgeable gulf in the goals of Inoue and his band members from those of the coup-related young officers. Even though they shared a common goal, i.e. a Shōwa Restoration, Inoue and his band had no interest in establishing a national socialist regime or, for that matter, promoting any political ideology. Their commitment was to one thing and one thing only – destruction, i.e. destruction of the existing order. As Onuma testified, following the band’s destructive acts it would be the work of others to create a new society.

Blood Oath Corps Trial

Contemporary observers may find it difficult to understand how a group of self-proclaimed revolutionaries could be dedicated to, or satisfied with, nothing more than destruction. The key to understanding this, however, lies in the nature of the emperor system as understood in 1930s Japan. That is to say, it was as inconceivable as it was unacceptable for a loyal subject of the emperor to impose any ideology whatsoever on the emperor, let alone force him to accede to the demands of his subjects. That is, however, exactly what the young officers, in concert with their senior military backers, intended to do had their coup been successful. Inoue was aware of this possibility and indicated that he and his band were prepared to kill all of the sympathetic, senior military leaders who would have assumed political power had the Young Officers’ Uprising been successful.40

This does not mean that Inoue had no interest in the major social reforms that were so important to both the young officers and Kita Ikki. Inoue, however, believed that once political power had been completely restored to the emperor, he would, of his own accord, initiate the reforms necessary to mitigate rampant poverty in the countryside; end the self-indulgent, luxurious lifestyle of the zaibatsu; and eliminate corrupt politicians and court advisors.

In this, it must be remembered that, like all Japanese of his era, Inoue had been taught from childhood that the emperor was the benevolent father of the Japanese people, all of whom were his children. Moreover, the emperor was the divine descendant of the Shinto Sun goddess, Amaterasu. Thus, as a benevolent father of divine origin, once the emperor had regained absolute power he would, of his own accord, do his best to ensure the happiness and well-being of all his children. Inoue explained:

The relationship between the emperor and the people of this country is the same as the relationship between a parent and his children. If the emperor weren’t our parent, why would he do his duty as a parent. It is for this reason we call him our “Great Parent.” If we weren’t the emperor’s children, why would we do our duty as children. For this reason, we are called “His Majesty’s children.” Not only this, but as history reveals, the emperor and the people of this country have always been one, differing only in their respective missions and stations in life. No matter what the organization, it is always made up of a center and its branches. The emperor is naturally at the center ruling over his subjects. It is for this reason that following the introduction of writing from China the phrase “sovereign and subjects are one” has been used to express Japan’s national body politic.41

Who Benefitted?

Now that the stark differences between the coup-related young officers and Inoue and his band is clear, the question becomes whether there is a connection between the lenient treatment Inoue and his band received and their professed lack of an ideological orientation, or, at least in their minds, their absolute loyalty to the emperor. I suggest the answer to this question revolves around the Latin phrase, Cui bono, “who benefits,” indicating there’s a high probability that those responsible for a certain event are the ones who stand to gain from it.

In this case there is no question that Emperor Hirohito stood the most to gain since the assassinations Inoue ordered, including the assassination of Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi, led to the end of political party-based cabinets, effectively ending parliamentary democracy and giving the emperor the power to appoint and dismiss successive prime ministers up through Japan’s wartime defeat.

This phrase has particular resonance in light of Bix’s insightful comments: “From 1927 onward the court group struggles to place the monarchy within a new ideological framework and, at the same time, find a way to break through the constraints on the emperor’s powers that had developed over the nearly fifteen years of the Taishō emperor’s debility.”42 Viewed in this light, Inoue and his band’s assassinations were literally “just what the doctor [or someone] ordered.” Bix continues:

The more the emperor involved himself in civil and military decision-making, the more deeply he and his closest aides became in deception, and the greater their stake in not ever admitting the truth. Under the Shōwa emperor, therefore, the operating conditions for correct governance required extreme secrecy and constant simulation, dissimulation, indirection and conniving on the part of high palace officials.43

And finally, just who were these “high palace officials” who surrounded and carried out Hirohito’s wishes. Bix explains:

From the beginning of the Shōwa era, Hirohito’s small, highly cosmopolitan court group advised him entirely outside the constitution. It was an enclave of privilege and the nucleus of the Japanese power elite, composed of men from the traditional ruling stratum and newly privileged and enriched groups from Meiji. Situated at the apex of the pyramid of class, power and wealth in Japanese society, the court group represented the interests of all the ruling elites of imperial Japan, including the military.44

This last quote makes it clear just how unlikely it was that Hirohito, let alone those close to him, would be sympathetic to major domestic reforms of a socialist nature. Moreover, as the earlier quotes note, it was not just Hirohito who set policy even if he was the one who granted final approval. Instead, he was ably assisted by some of Japan’s ‘best and brightest’, all of whom worked in an environment of secrecy and deception. Nevertheless, there are at least two well-known examples, previously introduced, that reveal just how this extra-constitutional process worked.