Abstract: At the heart of Northeast Asia lie multiple contradictions and unresolved issues left over from Japan’s militarist and colonialist past. Author Wada has written prolifically on both Japan-North Korea and Japan-South Korea matters and for the past 20 years has been a tireless advocate of what he calls the “Common Homeland” or “Common House” concept of a post-war and post-Cold War Northeast Asian regional community. Here he analyses the policy framework (established by Abe Shinzo, according to Wada) of Japan’s “hostility” towards North Korea and “ignoring” South Korea. He raises questions as to the compatibility of a Northeast Asian community with the recently articulated (US and Japan-promoted and China-encircling) “Indo-Pacific” concept.

Whoever takes office as Prime Minister in Japan inherits the policy towards the Korean peninsula established by former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo. The new Prime Minister promises to solve the abduction problem during his term of office, but is not allowed to cast any doubt on the three Abe principles. All he can do is to wear a Blue-ribbon Badge on his chest.1 Cries of praise for the king’s new clothes are endless even though everyone knows that he is naked. It is as if we are all living in a children’s story-book country.

The final version of Prime Minister Abe’s Korea policy was seen in his policy speech to the Diet on 28 January 2019, the final Diet sitting of the Heisei era [1989-2019]. He declared that he would undertake a complete overhaul of post-war Japanese foreign policy, carving out a new diplomatic path for Heisei and beyond. According to Abe, the security environment had “drastically changed,” and Japan could not just respond by continuing with its established policies. He declared that he would put finishing touches to the global diplomacy that Japan had practiced for the past six years under the banner of “positive pacifism.”

So far as neighboring countries were concerned, he would move the now normalized relations with China to a new phase, step up negotiations with Russia towards a peace treaty, and propose a new dialogue with North Korea:

“In order to resolve the North Korean nuclear and missile matters, and most important of all the abduction problem, I am prepared to meet face-to-face with Chairman Kim Jong-un, shedding the husk of mutual distrust and acting decisively, missing no opportunity to settle the unfortunate past and normalize inter-state relations. I will cooperate closely with international society, including especially the United States and South Korea.”

He concluded by declaring his resolve to build a “free and open Indo-Pacific.”

The Abe speech astonished me because it made no reference whatever to Japan-South Korea relations that had been cause for such concern since the end of 2018. It seemed to me that Prime Minister Abe was declaring that he was no longer treating South Korea as a negotiating partner. It reminded me of [former Prime Minister] Konoe Fumimaro’s statement during the Sino-Japanese war In January 1938, declaring “henceforth there can be no negotiation with the Kuomintang government” as he pressed ahead with war against China.

People might be surprised at the difference between earnestly seeking dialogue with North Korea while refusing to deal with South Korea. However, there is nothing particularly odd about it because what he had said about North Korea was an empty promise designed to give the impression of acting when he had no intention of acting. To his long continuing policy of hostility to North Korea Prime Minister Abe was adding a policy of ignoring South Korea.

1. Prime Minister Abe’s Hostile View of North Korea

First elected to the Diet in 1993, Abe Shinzo became Deputy head of the Parliamentarians’ League for Marking the 50th Anniversary of End of War, under Okuno Seisuke as head. It was his political debut. This organization proposed that there should be no resolution of critical reflection and apology over the Japanese aggression and colonial rule since Japan had fought for “survival and self-defense,” and “peace in Asia.” In 1995 their reactionary efforts bore no fruit as a 50th Anniversary of End of War resolution was carried in the House of Representatives and the Murayama [Tomiichi] Statement of apology for colonialism was adopted.2 Two years later, hoping to roll back this trend, Abe organized the Young Parliamentarians’ Association for Reflection on Japan’s Future and History Education and became its chief executive. Its purpose was to oppose the Kono Declaration and the teaching in schools about the Comfort Women issue. In 2000, when Abe became Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary and set up within government a project team to address the abduction problem, his hardliner proposals attracted attention. For this reason, he was not informed of the moves leading to the [Prime Minister] Koizumi’s visit to Pyongyang in 2002, but he accompanied Koizumi and subsequently garnered to himself the political support of the Sukuukai, the National Association for the Rescue of Japanese Kidnapped by North Korea, rapidly emerging as the leader of North Korea negotiation. The abduction issue was the key to his political rise. Eventually becoming Prime Minister in 2006, he identified the abduction as the key issue of his Cabinet. In his 29 September, 2006 policy speech in the Diet, he spoke as follows:

“Without resolution of the abduction problem there can be no normalization of relations with North Korea. In order to advance comprehensive measures on the abduction issue, I have set up an Abduction Measures HQ, headed by myself, with a full-time secretariat. Under the policy of dialogue and pressure, we will continue to strongly demand the return of all abductees, based on the premise that all abductees are still alive.”

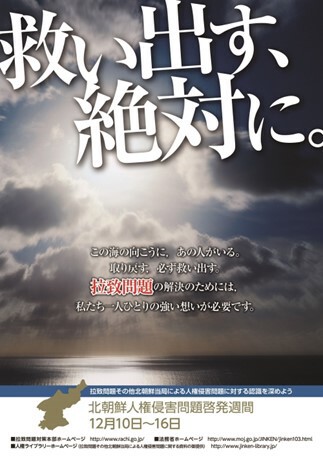

At the time of the Pyongyang meeting, North Korea apologized for the abduction of thirteen people, of whom eight had died and five survived. No matter how shocking the announcement of the eight deaths, and how unsatisfactory the explanations of the circumstances of their deaths, for Japan to insist the victims who were presumed dead were “all alive,” and to demand their return, was to treat the North Korean government as liars. Breaking off diplomatic negotiations and issuing this ultimatum was tantamount to simply demanding submission. This measure was undoubtedly in accordance with the thinking of the president of Sukuukai, Sato Katsumi, who declared “So long as the Kim Jong-il government exists it will be difficult to have any resolution of the abduction problem.” In 2006, launching an “North Korean Human Rights Violation Awareness Week,” Abe put out a newspaper advertisement pronouncing the North Korean abductions problem “the greatest problem Japan faces.” It became the first principle of the Abe Government’s North Korea policy. The second principle was that “without resolution of the abduction problem, there cannot be any normalization of relations with North Korea,” and the third was that “all the abduction victims are alive, and all must be returned.” From this time, all members of the Abe government took to wearing on their chest the Blue Ribbon Badge designed by Sukuukai.

The Sukuukai “Blue Ribbon Badge”

Thus, the Pyongyang Declaration’s admission of the “great damage and pain caused to the Korean people by Japan’s colonial control,” and Japan’s “heartfelt apology,” were forgotten. The Japanese posture of thoroughly pursuing North Korea’s aggression became established. As soon as North Korea started its nuclear tests, sanctions were imposed, and relations between Japan and North Korea quickly reached a state of complete breakdown, with trade and shipping cut off.

This Abe policy towards North Korea was softened under the subsequent Fukuda Yasuo government (2008-9) but then revived under Aso Taro government (2009-2010) and elevated to national policy under the following Democratic Party government (2009-2012). Under the Abe three principles, negotiations were impossible as one would have expected. No matter how much pressure was applied, the Kim Jon-il government could not be made to collapse. Then once Abe took office the second time around in 2012 and received the petition of the Kazokukai [Association of Abductee Families], he spoke of having been re-elected Prime Minister again in order to solve the abduction problem. He approved the Stockholm Agreement [2014] which was brought forward through the efforts of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and eventually requested the reopening of investigation of the abduction problem. However, when the interim report came out to the effect that eight had indeed died, Abe refused to accept it on the basis of his third principle. North Korea thereupon dissolved its re-investigation process.

As tension between US and North Korea reached a peak in 2017, Prime Minister Abe supported the President Trump position that all options were on the table. Abe went into a war mode, making statement such as that Japan would “step up pressure against North Korea,” and “strengthen Japan’s defence capabilities and do its best.” Under the 2015 revised security laws, an action plan was drawn up to align the Self Defence Forces with the US military. Communications were opened on a regular and ongoing basis between Kawano Katsutoshi, Chief of the Joint Staff of the Self-Defence Forces, General Joseph Dunford, Chair of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, and [Admiral] Harry Harris, US Pacific Commander-in-chief, and battle plans are said to have been drawn up.

However, fortunately US and North Korean leaders pulled back from the brink of extreme confrontation and suddenly shifted towards the June 2018 US-North Korea summit. Taken by surprise, Prime Minister Abe hastened to the US before the summit and called for “maximum pressure” and cooperation in solving the abduction problem. However, following the agreement between the US and North Korea, he too had to show he was ready for a summit [with North Korea]. But the three Abe principles would remain in place. He would wear the mask of dialogue, but his hostility towards North Korea would not change. His January 2019 policy speech was a consequence of this whole process.

Ministry of Justice Poster advertising “North Korean Human Rights Violation Awareness Week,” December 2016

2. Root Cause of the “Ignore South Korea” Policy

Why was the “Ignore South Korea” policy adopted on top of the hostility policy towards North Korea? Undoubtedly, Japan-South Korea relations had worsened since the end of 2018, with the South Korean Supreme Court judgements on the forced labour cases,3 the dissolution of the Reconciliation and Healing Foundation set up under the 2015 Japan-Korea agreement on the Comfort Women issue,4 and the [December 2018] incident of a South Korean naval vessel’s locking its radar onto a [Japanese] Self Defense Force aircraft. However, the Abe government’s dissatisfaction with President Moon Jae-in had been growing even before this time.

For Prime Minister Abe, who was intent on having the Kono statement rescinded, the 2015 Comfort Women agreement was difficult to swallow. But he was in a bind, under pressure from the persistent demands from South Korean president Park Geun-hye and also from the US. Biting his lip, for the first time he admitted government responsibility and apologized, and for the first time his government appropriated one billion yen in public funds towards helping the comfort women victims restore their honour and heal their psychological wounds. Abe attached conditions to the agreement: the apology was to be only in the form of a press conference by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, with no public text, and the disbursement out of public funds was to be one-off, with no follow-up measures. The Korean side should be understood to have agreed to take no further steps on apology in the form of a statement in documentary form, both Foreign Minster Kishida and Prime Minister Abe promptly refused. But with the advent of the Moon Jae-in presidency in South Korea the agreement was re-examined and opened to criticism from a victim-centred perspective. When the Government of South Korea appropriated one billion yen, proposing it substitute for the one billion put forward by Japan, the Japanese government reacted strongly. The problem was the breach of the agreement’s “final and irreversible” clause. That sentiment was reinforced by the Supreme Court decision in the forced labour case. Such criticism was created that raising again matters resolved by the “complete and final” clause in the Claims Agreement [of 1965] was a breach of international law.

3. Subsequent Development – Diplomatic Re-orientation and the Shift from North to South

The entry in the Diplomatic Bluebook also changed in 2019. It simply recorded the facts of the Japan-South Korea confrontation without reference to “shared basic values,” “shared strategic interest” or being “indispensable for the peace and security of the Asia-Pacific region.” In that year, when President Moon participated in the G20 Osaka meeting at the end of June Prime Minister Abe deliberately avoided him, not exchanging even small talk. Then in July the Government of Japan notified the South Korean government that it had decided to suspend the special measures concerning the export of materials essential for semi-conductor manufacture. Since semi-conductor manufacture is of critical significance for the South Korean economy this was clearly a hostile act. South Korea experienced great shock. The Government of Japan went on to delete South Korea from its list of “white countries” entitled to preferential trade control measures. Since Japan publicly stated that South Korea was not to be trusted on security matters, South Korea then threatened withdrawal from GSOMIA [the three-sided 2016 “General Security of Military Information Agreement”] with Japan.

The geo-political understanding spread through Japan’s media that the relationship with South Korea was no longer important. Kawai Katsuyuki, special diplomatic adviser to the Prime Minister, said in a television debate “the 38th parallel has shrunk south to the Tsushima Strait.” The selected articles called “The Disease Called Korea,” in the September 2019 issue of the magazine Hanada suggested the prospect of the whole of the Korean peninsula passing to the Chinese camp, with a continental bloc comprising China, Russia, North Korea confronting a US, Japan, Taiwan bloc (a league of maritime states). Such a view could be found also in the journal Bungei Shunju, whose special issue for September was entitled “Japan-Korea in flames – the Moon Jae-in government joins the enemy camp.” One lead article was entitled “Prospects after the export restrictions: Japan-US alliance versus unified Korea.” Keio University’s Hosoya Yuichi, Abe’s more up-market brain, spoke as follows in Yomiuri Shimbun of 18 August, saying “Geopolitically what counts for Japan is what happens in the two great countries, US and China, and compared to US and China, South Korea is relatively unimportant.”

When a group of journalists and scholars could not ignore this trend anymore and issued a statement, “Is South Korea the enemy?” on the Internet. In a 4 October policy speech, Abe said, “South Korea is our important neighbour,” but went on to say “I think pledges between countries should be faithfully observed, based on international law,” renewing his anti-Korea thinking. In December, he voiced a similar notion in talks with president Moon on the occasion of the Japan-China-Korea leaders meeting at Chengdu in China, saying that everything had been settled by the Japan-Korea treaty of 1965 and that it was against international law for South Korea to make requests of Japan. He did not hesitate to adopt such haughty posture in addressing South Korea.

4. The Suga and Kishida Governments

In the autumn of 2020 Abe resigned because of the worsening of a pre-existing health condition. In his opening speech on 26 October as successor, former Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide adopted in full the Abe line on North and South Koreas.

“The abduction problem will continue to be the biggest problem the government faces. I will do my best to secure the return to Japan of all the victims of abduction at the earliest possible date. I am prepared to meet directly and unconditionally with chairman Kim Jong-un. Based on the Pyongyang Declaration between Japan and North Korea I aim at a comprehensive resolution of the abduction, nuclear, and missile problems, settling the unfortunate past, and normalizing relations with North Korea.”

“South Korea is an extremely important neighbour country. Good relations must be restored with it. I will be firmly seeking appropriate responses based on the positions Japan has long advanced.”

However, on this occasion Prime Minister Suga emphasized a “free and open Indo-Pacific.” He said, “I have just completed visits to Vietnam and Indonesia. I will aim at realization of a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific,’ based on the rule of law and in cooperation with like-minded countries including ASEAN, Australia, India, the European Union.” Later, Prime Minister Suga visited the United States and offered in principle support for US China policy and cooperation in implementing the QUAD [Japan-US-Australia-India] security cooperation agreement. It meant distancing from Northeast Asia, shifting orientation southwards, and joining with the US in applying pressure on China.

Under pressure from popular mistrust over his handling of the COVID-19 health crisis, Prime Minister Suga resigned after just over a year and Kishida Fumio took over on October 3, 2021. Since it was he who, as Foreign Minister, had announced the 2015 Comfort Women agreement, one might think that he would strive to improve Japan-South Korean relations, making the most of the agreement, but such expectations were quickly dashed because, no sooner did Kishida take over as Prime Minister than, in response to a written Diet question from the Democratic Party’s Nataniya Masayoshi, on 19 October 2021 he repudiated the apology of 2015. Nataniya, referring to the following part of the Kishida statement in the 2015 agreement,

“The issue of comfort women, with an involvement of the Japanese military authorities at that time, was a grave affront to the honor and dignity of large numbers of women, and the Government of Japan is painfully aware of responsibilities from this perspective. As Prime Minister of Japan, Prime Minister Abe expresses anew his most sincere apologies and remorse to all the women who underwent immeasurable and painful experiences and suffered incurable physical and psychological wounds as comfort women,”5

asked whether, now as Prime Minister, Kishida intended to confirm and maintain such stance. Kishida replied evasively:

“On the matter of the comfort women, following discussions we secured the pledge of the government of South Korea to the agreement. Korean Foreign Minister Yun Byong-se declared in front of the people of Japan and South Korea and addressing international society… that the Comfort Women agreement was ‘resolved finally and irreversibly.’”

He hid the fact that Japan has apologised and said only that the Comfort Women issue has been finally settled. If that is the way Kishida runs away from the Korea issue, it is no surprise that his policy speech on 8 October was all about a “free and open Indo-Pacific.” He said Japan would “cooperate with allied and like-minded countries such as the US, Australia, India, ASEAN, the EU, engaging actively in the Japan-US-Australia-India group to promote a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific.’” The words he used in referring to the abductions were not the slightest bit different from those that Suga had used. Kishida met the Association of Abductee Families for talks, and on 13 November participated in a National Assembly to Demand Immediate and Total Return of all Abductees, where he referred to the abduction problem as “the most important problem facing the Kishida government” and said, “I strongly believe that I am going to be the one to settle the Comfort Women problem.” Most likely nobody among his audience believed that Kishida had any willingness to act or he thought he could act.

5. Is There a Way Forward for Japan?

Though negotiations began 30 years ago on normalization of Japan-North Korea relations, normalization has still not been accomplished and North Korea has become a nuclear armed country. That is the core of today’s crisis for Japan. If Kishida, a Prime Minister elected from a constituency that includes Hiroshima, victim of atomic bomb attack, is to speak of his ambition for a “world free from nuclear weapons” he should surely devote his every effort to deal with the nuclear weapons of a neighbour country. On 6 March 2017 North Korea launched four intermediate range ballistic missiles, three of which landed at a point 300 kilometres offshore from Akita City. On the following day, Korean Central News Agency announced that the missiles had been launched by [North Korean] artillery units that “were responsible for attacking enemy US imperialist bases in Japan in the case of unanticipated events.” It made clear that in the event of war between US and North Korea, North Korea would launch missile attacks on US bases in Japan. Nuclear-tipped missiles might be included. However great the nuclear defences, it is impossible to completely block such an attack. If North Korea contemplated how nuclear weapons might be used, the US would too far, and South Korea would be too near. We cannot be complacent and just think that Japan is protected by the US nuclear umbrella, will be OK because of the US-Japan Security Treaty. One of the most urgent tasks for Japan is to take active measures to eliminate such catastrophic possibility.

What the Japan that (in its constitution) has abandoned “the threat or use of force as means of solving international disputes” has available to it is peace diplomacy. If it really wants to block North Korean missiles it must aim to normalize the Japan-North Korea relationship and establish non-antagonistic, normal, and if possible, friendly and cooperative relations. It is clear that from such a viewpoint, the antagonistic Abe North Korean policy is the worst policy, exposing peace and security in Japan to crisis.

The Abe policies must be reversed. To solve the abduction problem the government of Japan will have to revert to diplomatic negotiations with North Korea. In the present circumstances, following the precedent of President Obama’s unconditional resumption of US relations with Cuba, normalization based on the Pyongyang Declaration could be implemented and ambassadors exchanged immediately. Germany, Canada, Australia,6 the Philippines all have diplomatic relations with North Korea. If Japan too were to open diplomatic relations negotiations could begin in Tokyo and Pyongyang on nuclear weapons and missiles and on economic cooperation and abductions. For the nuclear and missile problems especially prudent and honest negotiations would be required. On the abductions, the demand for all abduction victims to be returned alive should be dropped and replaced by the demand for the return of survivors and compensation for all victims. The issues that require protracted negotiation should be given time. Once diplomatic relations are opened, cultural exchange and humanitarian aid could be undertaken forthwith. Under cultural exchange probably an exhibition on the victims of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at Major cities in North Korea should be included. As for economic cooperation, negotiations would proceed on amounts and categories to be included and, if agreed, the outcome synchronized with agreement on nuclear and missile matters. Things would just have to proceed through gaining the understanding and support of stakeholder countries.

It is clear that the support and cooperation of South Korea is going to be necessary whether for normalizing Japan-North Korea relations or for reducing to zero the possibility of war between the US and North Korea. For that reason, the policy of “ignoring South Korea” is a fatal error. Currently the government of Japan, through its Ministry of Foreign Affairs, takes the view that matters to do with Japan-Korea relations were all resolved by the 1965 normalization treaties. However, the Japanese government, who at the time of signing of the 1965 treaties had an understanding that there was no need for Japan to regret or apologize, since the annexation [of Korea by Japan in 1910] was in accord with a treaty and therefore legal, did listen to the criticisms by South Korea after the democratisation of 1987, and from the Kono Statement to the Murayama Statement, adopted an attitude of reflecting on and apologizing for the harm and pain caused by the colonial rule. This was the basis of the 2010 Prime Minister Kan Naoto Statement and the 2015 Comfort Women agreement. It is a counter-historical outrage for things to have reached the current point where the slate is wiped clean of such developments and the Japanese government revert to the attitudes of the 1965 Japan-South Korea normalization treaty time.

The aggressiveness of the 35 years of Japanese colonial rule of Korea is an un-deniable historical fact when considering Japan’s relations with both Koreas, and the need for the Japanese people to repent and apologize knows no end. It is precisely through repentance and apology for colonial rule that we will be able to live in a normal, human cooperative relationship with people of South Korea and North Korea. Unless we build a situation in which the six countries – South Korea, North Korea, Russia, China, the US, and Japan can live together at peace, in a “common house,”7 it will not be possible to realize peace between Japan and North Korea, the US and North Korea, Japan and China, the US and China, and China and Taiwan. It is unlikely that the good ship Japan is going to be able to sail in free and open Indo-Pacific waters so long as Japan adopts a hostile attitude, or ignores, the people of the Korean peninsula.

Notes

Translator note: Reference is to the blue badge, discussed also below, symbol of the “National Association for the Rescue of Japanese Kidnapped by North Korea” (Sukuukai) and its demand that North Korea “immediately return all Japanese abductees.”

Translator Note: On 9 June 1945 the Japanese Diet adopted a resolution expressing “deep remorse for the “pain and suffering” Japan had inflicted on the region by its wartime actions, and on 15 August Prime Minister Murayama Tomiichi, addressing the Diet, spoke of “the not too distant past,” in which “Japan, following a mistaken national policy, advanced along the road to war and, through its colonial rule and aggression, caused tremendous damage and suffering to the people of many countries, particularly to those of Asian nations.” Statement by Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama, “On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the war’s end,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 15 August 1995.

Translator Note: The South Korean Supreme Court ruled in two cases in October and November 2018 that workers mobilized by Japan as forced labour during the war were entitled to financial compensation from Nippon Steel Corporation and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd, respectively. The Japanese government’s view was that all such property and compensation matters had been settled “completely and finally” in 1965 by the Agreement on the Settlement of Problems concerning Property and Claims and on Economic Co-operation between Japan and the Republic of Korea.

Translator Note: In December 2015, South Korea under the Park Geun-hye government and Japan under the Abe government jointly announced agreement to settle the ongoing “comfort women” issue. Japanese Foreign Minister Kishida Fumio’s announcement expressed “most sincere apologies and remorse to all the women who underwent immeasurable and painful experiences and suffered incurable physical and psychological wounds as comfort women.” Japan was to provide a ten billion won (ca $8.8 million) fund to establish a foundation to help restore the women’s “honor and dignity.” The Agreement was to resolve the issue “finally and irreversibly.” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Announcement by Foreign Ministers at the Joint Press Conference,” 28 December 2015. However, the agreement met much criticism from the victims and their supporters in Korea and internationally, for many reasons of which the primary one was that the neither of the two governments had had any consultation with the victims (see “The Flawed Japan-ROK Attempt to Resolve the Controversy Over Wartime Sexual Slavery and the Case of Park Yuha,” APJJF, 26 January 2016). The Agreement gradually broke down and the South Korean government under the Moon Jae-in government formally dissolved the Foundation in 2018.

Translator Note: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Japan-Republic of Korea Foreign Ministers Meeting,” 28 December 2015.

Translator note: Diplomatic relations between Australia and North Korea were opened in 1974, but have followed a checkered path, broken off in 1975, reopened between 2002 and 2008, but not restored since then. Relations are currently only conducted indirectly through the good offices of third countries.

Translator Note: Reference is to Wada’s concept of a North-East Asian “Common House” elaborated in his book, Tohoku Ajia – kyodo no ie (Northeast Asia – Common House), Heibonsha, 2003.