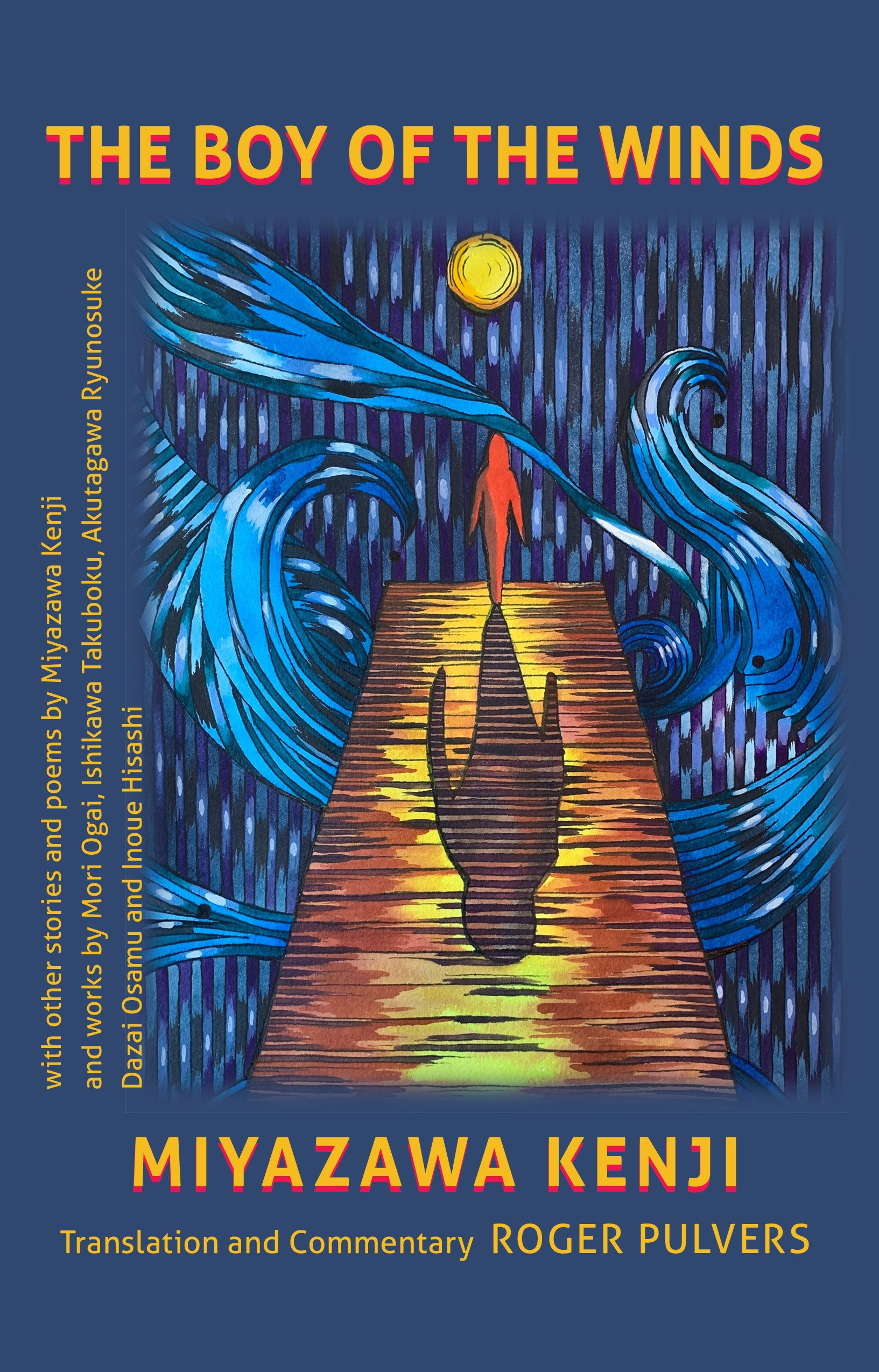

Cover Art by Lucy Pulvers (pulvers.co)

Mori Ogai (1862-1922), novelist, essayist, translator and one of the towering figures of the literary world in the Meiji and Taisho eras, was a master stylist. His prose style could not be farther away from the flowing, often seemingly random and excessively emotional, style of Miyazawa Kenji. It is controlled, concise, rational, formal, and chockablock with erudite Japanese and foreign historical references, the latter being chiefly classical Chinese and modern German. His style exerted an astounding influence on modern Japanese literature, inspiring an author born less than three years after his death, Mishima Yukio. Mishima, a master of clear and rich style in Japanese, took the pen directly from Ogai’s hand.

Ogai himself was inspired by his encounters with German culture. He was sent to Germany to study hygiene, particularly for its uses in the military. (Ogai was later promoted to surgeon general in the Imperial Japanese Army, becoming head of the Medical Division of the Army Ministry.) He arrived in Europe at Marseille on 7 October 1884 and went from there to Berlin. He spent his first year of study in Leipzig, going on to pursue his studies in Dresden and Munich. Before leaving Europe he stayed in Vienna, London and Paris, leaving, once again from Marseille and arriving back in Japan on 8 September 1888, for a span outside Japan of some four years.

The story “Hanako” appeared in print for the first time in the 1 July 1910 issue of “Mita Bungaku” (Mita Literature). Mita is the district of Tokyo where Keio University is located. The journal was established in that year at the university’s Literature Department by Kubota Mantaro, who had been taught by Ogai.

Ogai had heard third hand about the encounter between Rodin and Hanako from his son, who was told about it by his private tutor, the interpreter. The interpreter plays a major part in the narrative. Ogai’s oblique method of presenting it—in a sense the encounter between the two “main” characters takes place on the edge of the narrative—is fascinating. By looking askance, one can see the center more distinctly, a Japanese observational device recognizable in the woodblock print.

We don’t learn much about Hanako herself from the story that bears her name. Her real name was Ota Hisa and she was born in 1868, the year of the Meiji Restoration. Hanako was her stage name. Dying in 1945, exactly four months before the Japanese surrender, she spans the most tumultuous period, save perhaps for equivalent decades in the Heian Period, in her country’s history. (The home in Gifu that she was living in was destroyed in an American air raid and she passed away not long after it.)

Hanako joined a traveling troupe of actors and left Japan for Denmark in 1902. Her most significant encounter was with American dancer Loie Fuller, the so-called Goddess of Art Nouveau. Fuller also knew Rodin, who was enamored of her moving figure, as well as were Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha, for whom she modeled. It was Fuller who suggested her stage name of Hanako.

Hanako modeled for Rodin in 1906, after which she became friends with him and his wife. There are fifty-eight works of his based on her modeling, and two of them, both masks, were gifted to her. She took the two masks back to Japan, where she arrived in December 1921. Thanks to her selling them to a dealer in Tokyo, they were not destroyed in the bombing of her home. She was able to hold a single pose for a long time, maintaining the tension, and this impressed Rodin.

Rodin had spotted her on stage in Marseille on 18 July 1906. This encounter at the Colonial Exhibition occurred thanks to his having seen the Khmer dancers of the Cambodian Royal Ballet previously in Paris. (The dancers had accompanied King Sisowath, who had ascended to the throne two years earlier, on an official visit to France and the Exhibition.) Rodin was so taken with the dancers that he followed them from Paris to Marseille, making some one hundred and fifty drawings of the dancers, some of which he subsequently filled in in watercolors.

In Marseille he stopped in at a Japanese dramatic performance with the intriguing, if somewhat chilling, title “Revenge of the Geisha.” Hanako was the geisha. It is said that Rodin was inspired by her expression when she faced death by harakiri; but as women were not allowed to commit this ritual act (a privilege reserved for the presumably gutsier sex), I cannot vouch for the authenticity of the expression she managed to maintain. At any rate, Rodin requested a meeting with her and that led to the encounter described in “Hanako.”

The Hotel Biron, where Rodin maintained his studio, has had several names over its history. In 1916 Rodin bequeathed the studio and its contents to the French government, who opened it as the Rodin Museum dedicated to him and his work three years later. It is still there, on the Rue de Varenne in today’s Paris.

The contrasting way in which Kubota speaks to Rodin and to Hanako is very telling of Japanese society then and, to some extent, now. Though he is speaking French to the sculptor, Kubota’s dialogue is, needless to say, in Japanese in the story and is formal and highly respectful. The register drops like an elevator in free fall for Hanako, whose profession is totally deplorable to the educated interpreter’s mind. He is decidedly uncomfortable with this task and prefers the company of the books in the next room. Ogai is telling us as much about the Japanese male as he is about the Japanese female.

I have in my desk drawer a typed-out translation that I did of “Hanako” dated 1973 (not the translation below, which is a new one). The thing that I have always loved about this story is its remarkable point of view. You will look at many of Hokusai’s views of Mt. Fuji and not immediately focus on the mountain. He leads you to view it through the everyday life of the people of the district depicted or as a part of nature as a whole, that side-glance of the Japanese aesthetic.

Hanako is here for Ogai to comment on the aspiration of the artist: to get under the skin; to recreate the world inside the object, or person, under examination; to probe what makes a toy move; to expose what makes a human being tick.

“Hanako” is a beautiful example of a writer’s peripheral vision. Ogai, like Hokusai, looks to one side, then another in order to reveal the essence in the middle.

***

Hanako

Auguste Rodin entered his atelier in the Hotel Biron. The morning sun filled every corner of the spacious room.

The hotel was originally a luxurious structure built by a tycoon, but until not long before then had served as a convent for Sisters Servants of the Sacre Coeur. The young girls of Faubourg Saint-Germain would be assembled in this room and be led in hymns by the Sisters. The girls lined up in a single row and sang out with their pink lips parted like the mouths of chicks in the nest about to be fed by their mother. But you could no longer hear their animated voices now.

A different variety of animation, a different kind of life, now reigned in this room. This was a life without voice. And though it was devoid of voice, it nonetheless was a tempered, intense and palpitating life.

Mounds and lumps of clay sit on various pedestals and tables; and there are rough, angular pieces of marble elsewhere in the room. Rodin is in the habit of working on a number of projects simultaneously, turning to them as his spirit dictates, allowing them to grow naturally in the sunlight as flowers do on their plants. Some mature gradually; some, more swiftly. The power that his will exerts on form is astounding. His works come to life even when his hands are unmoving on them. From the instant he sets to work, he is able to muster the kind of concentration that normally would require hours of tedious labor in others.

Rodin, beaming, surveyed the half-finished head that he was working on. Its wide forehead. A bulbous knot of a nose in the middle. An ample white beard about the chin and jaw.

There was a knock at the door.

“Entrez!”

His vigorous voice, entirely unlike that of an old man, disturbed the still air in that room, and a thin man in his thirties with dark-brown hair and the look of a Jewish professor opened the door and entered.

“I have brought Mademoiselle Hanako for the appointment,” he said.

Rodin’s expression remained impassive as he watched this man enter and listened to what he had to say. He recalled the time that the Khmer king had visited Paris. The king had brought dancers with long slender limbs and supple bodies that, when they moved in their ways, bewildered and allured the observer. Rodin had held onto the dessins that he had hastily drawn of them at the time.

Every race, in this manner, has its own beauty. Rodin believed that it was up to a person to discover that beauty with his eye; and, hearing that Hanako was appearing in the variety theater in Paris, he had contacted her agent and asked for an appointment. The man who stood before him now was that agent, in a word, an impresario.

“Have her come in,” said Rodin.

The fact that he did not so much as point to a chair was not merely an indication of how little time he had.

“An interpreter accompanies her, sir,” said the impresario, respectfully.

“Who’s that? Is he French?”

“No, sir, he is a Japanese, a student at L’Institut Pasteur. He learned from Hanako that she would be visiting you, sir, and offered his services.”

“That will be fine. Let them both in.”

The impresario bowed and left the room.

Two Japanese entered immediately. Both of them were exceedingly small. They were followed by the impresario, who shut the door behind him. Though Rodin was by no means a tall man, the two Japanese barely came up to his ears.

A deep furrow appeared between Rodin’s eyebrows whenever he scrutinized objects, and so it did on this occasion. His gaze shifted from the student to Hanako, where it now lingered.

The student greeted Rodin and grasped his outstretched hand with its raised tendons. This was the hand that created Danaid, The Kiss and The Thinker. The student took his name card out of his card case and proffered it to Rodin: M. Kubota, Bachelor of Medicine.

“You are presently studying at L’Institut Pasteur?” said Rodin, glancing down at the name card.

“Yes, I am.”

“Have you been there long?”

“For three months now.”

“Studying hard?”

Kubota got a start. It was widely known that Rodin was in the habit of asking all students this very same direct question, and now it was his turn to answer it.

“Yes, very hard, sir,” he answered, vowing in his heart at that instant that he would apply himself to his studies and work until the day he died.

Kubota introduced Hanako. Rodin grasped her small sturdy hand as he ran his eyes down her little firm body, reading her, in this one long glance, from her clumsily set “butterfly” coiffeur to the tips of her toes visible in her thonged sandals.

Kubota could not help but feel a certain degree of embarrassment. He would have preferred to have been able to introduce a somewhat finer example of Japanese womanhood.

One can appreciate his embarrassment. Hanako was no great beauty. She had suddenly appeared on the stages of Europe, calling herself a Japanese actress. The Japanese living in Europe had never heard of such an actress, and, needless to say, this included Kubota. Far from being a beauty, she had the looks of a scullery maid, if I am not being too unkind to her. The skin on her limbs was soft and smooth and, by all appearances, she could not have done very much heavy work in her life. She was only sixteen and, as they say, in flower; and it is somewhat of a stretch to think of her as a housemaid. She rather resembled a girl just out of her childhood.

Rodin was pleased beyond all expectation. Here before him was a healthy, active young woman possessing a sturdy muscular frame without an ounce of fat below her thin pale skin, with muscles of evident tensile strength, a small face with a compact forehead and jaw, and an exposed neck. Rodin was delighted as well with the fact that the muscles in those gloveless hands, arms and entire body seemed to be throbbing with energy.

He put out his hand to her and she, well accustomed to European ways, grasped it with an amiable smile on her lips.

Rodin offered them both chairs.

“May I ask you to wait in the drawing room?” he said, turning to the impresario.

After the impresario left the two Japanese sat down.

“Are there mountains in Mademoiselle’s birthplace?” asked Rodin, opening a box of cigars. “Or is the sea nearby?”

Hanako, as a woman making her own way in the world, had a series of set phrases prepared to answer people’s questions, much like the little girl in Zola’s Lourdes who gets on the train and recounts the miracle of how her leg was cured. Hanako’s story thus resembled one written by a novelist practiced in routine. But Rodin’s unexpected question had fortunately shattered this pattern.

“The mountains are quite far, sir. We are by the sea.”

Rodin was pleased with this answer.

“Did you often go boating?”

“Yes, I did.”

“Did you row the boat yourself?”

“No, my father did. I was still little then.”

Rodin conjured a picture in his mind’s eye. He fell silent for a few moments. He was a man of few words.

“Mademoiselle is familiar with my profession, I trust,” he said without transition, turning to Kubota. “Would she remove her kimono for me?”

Kubota did not reply at once. For anyone but Rodin he would have refused outright his services as an intermediary for such a thing as asking a Japanese woman to pose unclothed. But seeing as this was for Rodin, he had no objection. He did not feel obliged to give it another thought. He simply hesitated because he was unsure as to what Hanako would say.

“I will ask her and see.”

“Please do.”

“The master has something he wishes to ask of you,” he said to Hanako. “He is the world’s greatest living sculptor and he sculpts people’s bodies. I mean, even you know that much. That’s what he wants to ask you, if you’ll pose without your clothes on for him. So, what do you say? I mean, take one look at him. He’s such an old man. He’s pushing seventy. As you can see, he’s past the age of foolishness. So, you up for it?”

Kubota fixed his eyes on Hanako, wondering whether she would blush from bashfulness, assume an affected air or, perhaps, protest.

“I will oblige him,” she said candidly, without blinking an eye.

“She has consented,” said Kubota to Rodin in French.

Rodin’s entire face lit up. He rose from his own chair and placed some paper and chalk on the table.

“Do you choose to remain here?” he asked Kubota.

“In my profession I have been called upon at times to decide whether my presence is necessary. However, in this case I feel it might make Mademoiselle Hanako uncomfortable.”

“I see. We should be finished in fifteen or twenty minutes. Please be so kind as to wait in the library,” he said, indicating a side door. “And do help yourself to a cigar.”

“He says that it’ll take only fifteen or twenty minutes,” Kubota told Hanako.

He took a cigar for himself and receded into the library.

* * *

There were doors on both sides of the modest room that Kubota entered, but only a single window with a plain bare table below it. Bookshelves lined the walls on both sides of and opposite the window.

Kubota stood stationary for some moments, running his eyes over the lettering on the leather spines of the books. They were in no special order; and it looked very much as if they had been placed according to the chance of their acquisition. Rodin was a dyed-in-the-wool bookworm who had collected books from the time he had wandered Brussels as a poor young student. Among the old and soiled books there were those that obviously had a special meaning for him; and that is no doubt the reason why he had brought them there.

The ash from his cigar was about to drop, so he walked to the table and flicked it into an ashtray. He picked up a book that happened to be there. It was an old book in a gilded leather binding, and he took it to be the Bible. But when he opened it, he realized that it was a pocket edition of The Divine Comedy. Another book, lying on an angle in front of it, was a volume out of the complete works of Baudelaire.

He opened the book to the first page, with no particular desire to read it, to find that it contained the essay on “The Philosophy of Toys.” Out of sheer curiosity he began to read.

When Baudelaire was a little boy he was taken to someone’s home where a little girl lived. This little girl had a roomful of toys. The essay goes on to say that the girl invited him to play with any one of them.

When a child plays with a toy, he inevitably feels the need to break it open. He will want to see what makes it the toy that it is. In the case of a moving toy, he will want to find out what drives it. Children turn from the physical to the metaphysical. They are intrigued by metaphysics more than by physics.

Kubota found himself caught up in this fascinating essay of a mere four or five pages’ length.

It was then that there was a knock at the door, and it opened.

“I beg your forgiveness,” said Rodin, sticking his hoary head through the doorway. “You must be frightfully bored.”

“Not at all. I have been reading Baudelaire,” said Kubota, returning to the atelier.

Hanako was already making preparations to leave. Two sketches lay on the table.

“What of Baudelaire were you reading?”

“The Philosophy of Toys.”

“The form and structure of the human body, as with those toys, is not interesting as form and structure. It is a mirror of the spirit. What is interesting is the flame inside, the flame that one can see in the form.”

Kubota discreetly stole a glimpse at the sketches.

“They’re much too rough for you to tell anything,” said Rodin, adding, after a long pause, “Mademoiselle has a very beautiful body. She has no fat, and her muscles float to the surface, each one remaining a separate entity. They are like the muscles of a fox terrier. Her tendons are firm and thick, and the joints in her arms are as large as those in her legs. Her legs are so sturdy that I have no doubt but that she could stand forever on one leg with the other leg thrust out on a right angle. She is like a tree with its roots deep in the earth. She is unlike the Mediterranean type with broad shoulders and a wide waist. She is also unlike the Northern European type with wide waist and narrow shoulders.

“She embodies an aesthetic of strength.”

Mori Ogai’s “Hanako” is included in the edited collection Miyazawa Kenji, The Boy of the Winds, Translation and Commentary by Roger Pulvers with other stories and poems by Miyazawa Kenji and works byMori Ogai, Ishikawa Takuboku, Akutagawa Ryunosuke, Dazai Osamu and Inoue Hisashi (Balastier Press).