Abstract: The summer of 2018 saw an unprecedented series of LGBT-led political demonstrations in Japan involving thousands of people. They emerged in reaction to an article written by conservative Liberal Democratic Party lawmaker Sugita Mio which stated that LGBT couples “did not have productivity” because they could not have children. The article engendered an unprecedented backlash, as LGBT activists argued that Sugita’s notion of productivity attacked not only LGBT people but other so-called “unproductive” groups. This paper analyzes the political context and significance of the 2018 protests and shows how LGBT activist strategies have evolved and responded to changing social and political conditions in Japan.

Keywords: LGBT, Sugita Mio, productivity, protests, children, gender equality

Introduction

In July and August of 2018, a series of large-scale protests by lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) activists and allies were held in Tokyo, Osaka, and other cities across Japan. The immediate trigger for the protests was an article written by a lawmaker named Sugita Mio of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) which argued that LGBT couples should not receive government support because they could not have children and therefore were not productive. Organized by a small group of activists on social media over the course of a few days, the demonstrations attracted thousands of participants and drew attention from both domestic and international media. In both contemporaneous and subsequent accounts, participants stressed that the protests were not simply a reaction to a single article by one politician, but rather sought to draw attention to larger issues surrounding homophobia and transphobia and to reframe these issues by situating them in the context of discourses over economic and demographic productivity (seisansei) in contemporary Japanese society. The 2018 protests have had a significant impact on subsequent activism and perceptions of LGBT issues; as one nonprofit LGBT rights organization put it, in the eyes of many activists, they represented “Japan’s Stonewall.” 1

Figure 1: A group of protesters at Shibuya Station, Tokyo, August 5, 2018.

Photo by Tomomi Yamaguchi, used with permission.

Since the 1990s, LGBT activists and organizations in Japan have vacillated between confrontational and conciliatory rhetorical strategies in the political arena. After a wave of mainstream media visibility and rise in public discussion of gender and sexuality related issues in the early to mid-1990s, the 2000s saw a backlash against gender-equality focused initiatives that positioned sexual minorities as threats to the demographic health of the nation. In the 2010s, Japanese activists, influenced by international developments in LGBT politics, sought to promote LGBT rights by framing LGBT people as uniquely creative and productive. They framed LGBT rights in nonconfrontational terms and portrayed supporting LGBT people as a way for private companies and municipal governments to expand their economic power and international influence.

The 2018 protests, however, suggest a shift from the dynamics that characterized earlier activism. In response to Sugita’s comments, activists did not attempt to frame LGBT people as productive but instead linked LGBT marginalization to the struggles of other social groups deemed “unproductive,” in Japan, including single women, the elderly, and people with disabilities. This framing enabled the protests to build widespread support and to connect the struggles of LGBT people to a broad array of marginalized communities. As debates over LGBT rights and the meaning of productivity continue to intensify, the 2018 protests suggest the potential for activists to use new rhetorical and discursive strategies to challenge negative depictions of LGBT people. The issues identified by LGBT activists during the 2018 protests have only become more salient in Japanese politics since, particularly as debates within the LDP over how to approach LGBT rights have intensified.

This article traces the history of these debates and examines the demonstrations of the summer of 2018 as an inflection point for LGBT issues in Japan. It begins with an account of the July 2018 essay written by Sugita and contextualizes it as part of a series of debates on LGBT rights in Japan beginning in the 2010s. It then traces Sugita’s rhetoric to a natalist and conservative backlash against gender equality reform efforts that began in the late 1990s and the mid-2000s, where pro-LGBT initiatives had been framed by critics as being part of a feminist led effort to create a radical, ‘gender-free’ society. It then analyzes responses and protests to Sugita’s article and other anti-LGBT comments by LDP politicians in July and August of 2018. I argue that in order to understand the protests and the politics of LGBT rights in contemporary Japan more broadly, it is necessary to also understand the politics surrounding productivity (seisansei), a term which can refer both to productivity in general and to reproductivity. The article concludes by examining the ongoing legacy of the protests, outlining some of the developments since 2018 and assessing their significance for future LGBT politics and activism in Japan.

Summer 2018 in Context: The ‘LGBT Boom’ and Backlash in 2010s Japan

The 2010s saw a remarkable rise in LGBT visibility in mainstream Japanese media and politics, to such a degree that some commentators have called it an “LGBT boom.” 2 According to a 2018 report by the research firm Dentsū Diversity, 70% of the public reported being familiar with the term LGBT, an increase of more than 30% from three years earlier.3 This boom has been fueled by both economic and political forces. Beginning in the early 2010s, Japanese corporations started to take an increasing interest in the financial potential of LGBT consumers. In 2013, the business magazine Shūkan Daiyamondo published a special issue on Japan’s “LGBT market” describing it as potentially worth 5.7 trillion yen to investors.4 Furthermore, in March 2015, Shibuya Ward in Tokyo made history when it became the first municipality in the country to implement a same-sex partnership (hereafter SSP) ordinance.5 Shibuya’s ordinance was followed by the creation of similar ordinances for same-sex partnerships in other municipalities including Setagaya Ward, Takarazuka City, and Sapporo City.

The Japanese LGBT boom of the 2010s was also influenced by shifts in international LGBT politics. In 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Council voted to commission a report documenting anti-LGBT laws and violence in member states around the world, and in 2014 approved a declaration calling sexual orientation and gender identity fundamental human rights.6 That same year, Russia, the host of the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, came under international criticism for a law it had passed the previous year prohibiting positive depictions of “non-traditional sexual relationships.” One journalist described the widespread protests and criticism over the law as “a barometer for the international politics of LGBT rights,” and the Sochi Olympics as “the most geopolitically charged since the Soviet-boycotted 1984 Summer Olympics.” 7 As a result of the controversy, in December 2014 the International Olympic Committee (IOC) amended the nondiscrimination principle in the Olympic Charter to include sexual orientation as a protected category for future games.8

The 2014 amendment to the IOC Charter was particularly influential in Japan, which had been chosen to host the 2020 Summer Olympics in September 2013. Around this time, some LDP politicians became more publicly receptive to LGBT rights. In response to the Olympic Charter change, in March 2015 LDP representative Hase Hiroshi, then head of the party’s Olympic planning committee in the Diet, partnered with Hosono Gōshi of the Democratic Party of Japan to form an intra-party Diet committee to examine LGBT issues in Japan.9 This was followed by LDP member Inada Tomomi announcing the creation of an internal LDP Special Committee on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (hereafter referred to as the LDP SOGI Committee) following a trip to San Francisco in late 2015. Inada’s sudden interest in LGBT issues during this period came in contrast to her reputation as a conservative stalwart and Abe ally in the 2000s. In 2009, Inada spoke out against an initiative by the then Democratic Party of Japan-led government to allow registrations for marriages abroad (todoke-in) to be printed for same-sex couples living in countries where same-sex marriage was legal, asking “Why does the government intend to reserve policies and send registration forms endorsing same-sex marriage abroad when same-sex marriage is not recognized in Japan? Is it acceptable for the [Ministry of Justice] to act as if it can monopolize the debate around an extremely important issue that directly affects Japanese morals and values?” 10 In a subsequent interview, however, Inada credited meeting conservative LGBT activists in the United States with changing her perspective on LGBT issues.11 She argued that support for LGBT couples, many of whom, she noted were conservatives, should be seen as part of the LDP’s broader efforts to promote pro-natalist policies to combat demographic decline. In a blog post from December 2015, Inada positioned her newfound LGBT support in non-ideological terms, stating that it was neither liberal nor conservative but instead “a politician’s duty,” to “create a society where all people are given a chance.” 12

The shift in LGBT issues by Inada and others, however, was not universally accepted in conservative political and intellectual circles. In March 2015, the month that the Shibuya Ward Ordinance for the Promotion of a Diverse and Gender Equal Society (Shibuya ku danjo byōdō oyobi tayōsei wo sonchō suru shakai wo suishin suru jōrei) was proposed and passed by the Shibuya Municipal Assembly, right-wing organizations including the nationalist Ganbare Nippon held demonstrations against the proposal in Shibuya Square, where flyers were distributed that accused the ordinance’s proponents of trying to “destroy the traditional family.” 13 Following its passage, the conservative magazine Seiron published an editorial by Reitaku University law professor Yagi Hidetsugu describing it as an “extreme form of gender-free ideology.” 14 In response to the ordinance, some members of the LDP such as Lower House member Shibayama Masahiko, argued that the ordinance and other efforts to legitimize same-sex partnerships would accelerate the nation’s childbirth decline.15 Other party members went further; at a meeting of the party’s Special Committee to Protect Family Bonds that March, officials called the ordinance an attack on traditional families, and one member was reported to say that just thinking about same-sex couples was disgusting.16

Ideological differences within the LDP over LGBT rights became increasingly apparent by the end of 2015. When the LDP SOGI Committee was formed in 2016, it was headed not by Inada but by Furuya Keiji, a conservative party stalwart aligned with then-Prime Minister Abe Shinzō.17 According to the journalist Nikaidō Yuki, this personnel decision was made to placate more conservative members of the LDP, who had criticized the proposed formation of the committee altogether. At a closed-door meeting in March 2016, members of what Nikaidō describes as the party’s “natalist right wing” (kazoku uyoku ha), including lawmaker Yamatani Eriko, as well as conservative intellectuals such as law professor Yagi Hidetsugu pressured the party to disband the committee altogether. In an April 2016 editorial for the magazine Seiron, Yagi went on to argue that because “children can only be born between men and women,” the government had a responsibility to “prioritize heterosexual relationships above other ‘sexual orientations.’” 18

As a result of this internal pressure, the LDP repeatedly emphasized that the party’s SOGI Committee would seek to “increase understanding,” of sexual minorities, but not necessarily make legal changes. At the committee’s inaugural meeting, Furuya made clear that the committee would not pursue legislative reform, stating that it would be unsuitable to “create reports and advocate for human rights related legal proposals” in a way similar to “certain activist groups.” 19 Rather than trying to “legally change the entirety of society” he said, it would seek to promote a “proper understanding” (tadashii rikai) of sexual minorities in the form of an “LGBT Comprehension-Raising Bill,” (LGBT rikai zōshin hō). As a result of the party’s shift in emphasis, the intraparty Diet Committee on sexual minority issues established in 2015 by Hase and Hosono fell apart, as four opposition parties jointly submitted a comprehensive anti-LGBT discrimination bill to the Diet in March 2016.20 In subsequent publications, the LDP SOGI Committee has sought to emphasize what it describes as Japan’s historical and cultural tolerance towards sexual minorities. A pamphlet outlining the LDP’s stance on sexual minorities published by the committee frames LGBT discrimination as an issue of a “lack of public awareness,” and states that “historically, Japan has not been harsh towards diverse gender and sexual minorities but has instead been tolerant towards them.” 21

To understand the shifting status of LGBT rights within the LDP, it is necessary to look at how demographic and economic decline have impacted the party and Japan more broadly over the past three decades. Since the 1990s, efforts to reverse Japan’s ongoing childbirth decline have been a feature of every LDP-led administration, and these efforts became more pronounced during the second Abe administration, which also began to emphasize the rhetoric of productivity (seisansei) in its social and fiscal policies.22 In 2017, Abe announced a national budget with a new set of policies aimed at incentivizing economic and population growth. Included in the package was a change in the consumption tax to invest more than 700 billion yen towards eliminating education and childcare fees for children between the ages of 0 to 5.23 Advertising these new policies under the slogan of “a revolution in productivity and a revolution in human development,” (seisansei no kakumei to hitodukuri no kakumei), Abe linked these policy proposals to efforts to support small and medium sized businesses, which he described as “directly confronting a severe shortage in manpower.” 24 By linking natalist policies to his efforts to boost Japan’s economy, Abe successfully repositioned the issue of productivity in demographic as well as economic terms. To understand why his administration felt it necessary to connect natalist policies and efforts to raise economic productivity, we must first examine how discourses linking demographic decline and the ostensible crisis of the traditional Japanese family emerged in the backlash to gender-equity and pro-LGBT initiatives beginning in the late 1990s.

The ‘Gender-Free’ Debate and Post-Backlash LGBT Rights Discourses

The 1990s saw the passage of numerous gender-equity initiatives at the regional and national levels across Japan. This period culminated in the passage of the 1999 Basic Law for a Gender Equal Society, which established offices around the country to promote feminist and LGBT-inclusive human rights efforts. A number of these offices subsequently drafted human rights charters that, among other things, called for sexual orientation (seiteki shikō) and gender identity (sei jinin) to be respected as fundamental human rights.25 These reforms coincided with Japan’s so-called “Lost Decade,” as successive domestic crises occurred in the late 1990s against a backdrop of acute economic stagnation and demographic decline.26 In this context, feminist efforts to create stronger protection for women in the workplace and to legalize the use of separate surnames for married couples were framed by critics in alarmist terms and portrayed as threats to the ‘traditional Japanese family’ (dentōteki na kazoku).27 The backlash against these efforts coalesced in the late 1990s around the term “gender-free” (jendā furī), a term first used by the Tokyo Women’s Foundation in 1995 and appropriated by conservative critics who argued that recent gender-equity efforts were ideological attempts to erase gender differences (seisa) between men and women and would accelerate the country’s perceived decline.28 In late 2001 and 2002, the right-wing organization Nippon Kaigi, the largest grassroots conservative group in the country, used the term repeatedly to criticize a broad range of legal and educational reform efforts and brand their proponents of being the “destroyers of Japan.” 29

In the backlash discourse, LGBT people, who had gained a degree of mainstream visibility during the ‘gay boom’ of the 1990s, quickly became targets of right-wing criticism. Kazama Takashi argues that jendā furī critics cast support for sexual minorities as a plot to eliminate sex differences and create “genderless humans” (chūsei ningen), a rhetorical framing he says drew extensively from transphobic and homophobic tropes.30 Queer studies scholar Shimizu Akiko writes that conservative critics “claimed that feminists and the advocates for what they called ‘gender-free movements’ were denying sexual difference, creating a new generation of ‘gender confused’ and/or bisexual children, and destroying traditional Japanese families and communities.” 31 Subsequently, LGBT people were cast as a “freak new species,” that would “lead to the further deterioration of the country’s morality and economy.” 32

Early attempts by jendā furī critics to organize opposition to nascent pro-LGBT initiatives can be seen in efforts to remove language affirming freedom of sexual orientation in municipal-level human rights charters and gender equality ordinances that occurred in Tokyo in 2000, Miyakonojō, Miyazaki in 2003, and Yame, Fukuoka in 2004. In the Tokyo case, then Tokyo governor Ishihara Shintarō justified the removal by saying homosexuality was a personal preference, while in Miyakonojō, the conservative newspaper Sekai Nippō accused the charter’s drafters of trying to make the town into a “homosexual liberation zone” (dōseiai kaihō ku).33 Another example of anti-LGBT backlash in the early 2000s can be seen in attacks on gender-inclusive education reform efforts. One of the first high-profile targets of right-wing critics was the 2002 textbook Love and Body Book for Middle School Students. A sex education textbook for middle-schoolers that emphasized “inclusive sex education,” the textbook was published under the aegis of the Basic Law for Gender Equality and included detailed information on birth control, sexual assault, and same-sex attraction.34 In 2002, Lower House representative Yamatani Eriko, then a member of the Democratic Party of Japan, criticized the textbook in a speech to the Diet, arguing that it advocated birth control to teenagers and was unsuitable for public education. Other politicians and conservative intellectuals soon joined in on the criticism of sex education reform efforts. In 2005, the conservative scholars Yagi Hidetsugu and Nishio Kanji co-wrote a book titled New Negligence of Citizens: Gender-Free and Extreme Sex Education Will Lead Japan to Extinction that portrayed sex education initiatives as part of a plot to introduce ‘free sex’ to students, with the ultimate goal of creating “okama classes” and the destruction of Japanese culture.35 The backlash did not just extend to sex education but targeted other gender-inclusive education reforms more broadly. In early 2004, the Yomiuri Shimbun published a survey that found a growing number of Japanese youths who rejected traditional gender roles. The survey was cited in comments to the Diet by DPJ member Nakayama Yoshikatsu, who warned that jendā furī education reform threatened to undermine “natural sex differences,” and thereby the security of the nation itself.36

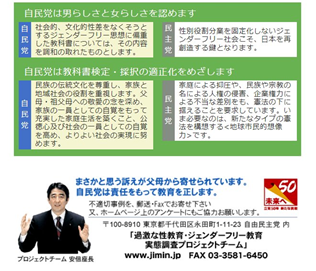

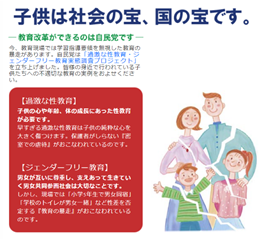

By the mid-2000s, the LDP sought to utilize the anti jendā furī backlash politically. According to Shimizu, the backlash was actively encouraged by the party and “just as blatantly and systematically led by the national government as it was fueled and upheld by the grass-roots moral/religious conservatives who are the major constituency of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party.37 The LDP announced the formation of the Project Team For Investigating the State of Radical Sex Education and Gender Free Education in the Diet in March 2005, which was jointly led by Yamatani and future prime minister Abe Shinzō.38 As well as setting up a hotline where parents could report “inappropriate” examples of sex education, the project team initiated a larger public awareness campaign to warn the public of gender-inclusive initiatives. The team also amplified the voices of conservative critics of these initiatives; at a 2005 symposium organized by the team, Yagi Hidetsugu was invited to give an address in which he decried sexual education reform efforts as ‘Marxism’ and declared the team’s purpose to be the “restoration,” (kenzenka) of healthy school education.39

Fig. 4 & 5: Screencaps from the LDP Project Team to Investigate the State of Radical Sex Education and Gender Free Education in the Diet Website, 2005. Note the image promoting Project Team head and future Prime Minister Abe Shinzō at the bottom of Figure 3.

Source: LDP Project Team Website, 2005 [Accessible via Wayback Machine, Twitter Archive)

Many of the figures associated with the Project Team including Yagi and Yamatani went on to become high-profile critics of LGBT-inclusive initiatives in the 2010s. The influence of the team’s framing of LGBT rights is reflected in the conservative rhetoric of other LDP politicians in the 2000s and 2010s. In a 2005 report, the team argued against recognizing same-sex partnerships by stating that using tax funds to support “individual lifestyles,” would “destroy our country’s traditional family system.” 40 Similar rhetoric was also espoused by Abe himself in his 2006 book Towards a Beautiful Country. In the work, written shortly before his first stint as Prime Minister, Abe criticized textbooks that positively depicted nontraditional families including same-sex couples and single parents, and called for educators to “propagate a model of family that is proper for children.” 41 Such descriptions would be echoed in the arguments made by Sugita’s 2018 essay, in which she states that LGBT couples lack productivity and thus should not qualify for state support.

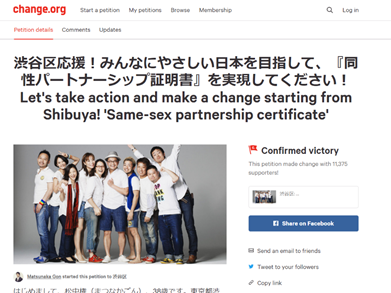

Since the backlash of the 2000s, many of the most visible and successful campaigns by Japanese LGBT activists in the 2010s have emphasized the rhetoric of tolerance, diversity, and the economic potential of LGBT people in place of rights-centered discourses. The 2015 Shibuya SSP ordinance provides an example of this framing. As Yokō Toshinari has noted, proponents of the ordinance strongly emphasized universalizing and non-confrontational language of diversity, tolerance, and love in their efforts to build public support.42 In an April 2015 interview, Shibuya Ward mayor Hasebe Ken, one of the major backers of the SSP ordinance, rejected the idea it was motivated by human rights concerns, and instead framed it in terms of economic development. Describing the ordinance as a means of showcasing Shibuya’s diversity, internationalism, and soft cultural power, he positioned it as part of a larger goal of making Shibuya “the most creative city in the most creative country in the world.” 43 Kawasaka Kazuyoshi argues that the strategic deployment of the term diversity (tayōsei) allows for the superficial incorporation of the interests of marginalized groups while enabling the continuity of preexisting social and political structures. As he notes, while the term diversity appears in the title of the Shibuya ordinance, the ordinance lacks meaningful legal protections for same-sex couples, thereby suggesting it was implemented more in the interest of signaling diversity than addressing inequities faced by LGBT people.44 Shingae Akitomo further argues that LGBT activism in the 2010s saw a ‘diversity boom’ as activist groups increasingly utilized rhetoric derived from corporate diversity management.45 He argues that activists have embraced the term as a way of emphasizing LGBTQ people as uniquely productive, borrowing from corporate strategies that frame diversity as a means of increasing economic and corporate productivity.

This shift towards non-confrontational rhetoric and an emphasis on the benefits of diversity reflects what Lisa Duggan has described as the widespread adoption of neoliberal rhetoric and corporate decision-making models by LGBT activist groups beginning in the 1990s. According to her, this corporate model of activism “does not contest dominant heteronormative assumptions and institutions, but upholds and sustains them, while promising the possibility of a demobilized gay constituency and a privatized, depoliticized gay culture anchored in domesticity and consumption.” 46 The shift also reflects what Myrl Beam calls the “love pivot,” of LGBT politics and characterizes it as a pragmatic rhetorical shift towards framing LGBT issues through the “depoliticized and private,” lens of love, associatively linking LGBT people to “normative ideas about family, nation, and duty.” 47 A pivot towards the rhetoric of ‘love and diversity’ can be seen in the planning of the Shibuya SSP ordinance. While planning the initial proposal, Shibuya Ward Mayor Hasebe Ken observed that “While many have attempted to make appeals for LGBT rights from the viewpoint of ‘human rights,’ I wondered whether there might be a different approach more suitable to Shibuya Ward. I felt that we needed logic that people could understand and accept in their hearts rather than their minds.” 48 When the ordinance was initially proposed, activist Matsunaka Gon started a bilingual Change.org petition in favor of it that garnered more than 10,000 signatures. Matsunaka strongly emphasized the importance of love and diversity in the petition, writing that “Love and care that LGBT couples have for their partners are no different from those of the straight one[sic],” and stating his belief that “this plan is a good opportunity for Japan to be a country with greater appreciation of diversity.” Another activist central to the planning and promotion of the Shibuya ordinance, Sugiyama Fumino, reflected on the strategies activists adopted to build public support for it in a later interview, stating that “The more we emphasize demands for political rights, the more divisions we create between those who are sexual minorities (tōjisha) and those who are not (hitōjisha). What is important for us is creating opportunities for LGBT people and non-LGBT people to meet and connect with each other.” 50

|

Figure 6: A screenshot of a petition on the website Change.org in support of Shibuya Ward’s Same-Sex Partnership Ordinance started by Matsunaka Gon in February 2015. |

By emphasizing diversity in corporate and economic terms and love as an apolitical, unifying force, some Japanese LGBT activists have responded to jendā furī critics by framing LGBT people as uniquely productive in both economic and demographic terms.51 Given the historical significance of the Shibuya Ordinance SSP, it is clear that the activist strategies employed there and elsewhere since the 2010s have achieved a measure of success. Yet, as previously noted, they have been criticized as prioritizing representational victories over material issues including poverty and homelessness. Some critics have also noted an irony in the fact that even as Shibuya Ward has attempted to position itself as a bastion of diversity, it has simultaneously engaged in aggressive efforts to privatize public spaces and force homeless residents from municipal parks.52 Furthermore, the ‘love and diversity’ strategy has failed to placate critics who continue to portray LGBT people as threats to the traditional family and Japan’s demographic stability. While some LDP politicians have tentatively embraced LGBT rights in the context of internationalization (kokusaika), others portray LGBT people as a threat to the nation’s economic, moral, and demographic health, echoing the backlash discourse of the 2000s. It is in this context that Sugita’s July 2018 essay on the ostensible productivity of LGBT couples must be understood. In the following section, I outline Sugita’s essay and the responses it engendered on social media and in the form of demonstrations in July and August of 2018. While Sugita’s rhetoric about LGBT couples was not new, as the next section will show, the size and scale of the reactions her essay provoked was unprecedented.

“The Level of LGBT Support is Excessive,” and Responses, July-August 2018

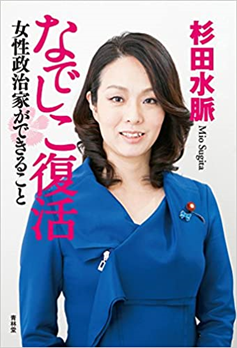

Sugita Mio was first elected to the House of Representatives of the Diet from Hyogo Prefecture as a member of the Restoration Party of Japan (Nippon Ishin no Kai) in 2012 before later joining the LDP. She began her political career as an outspoken opponent of feminist initiatives. In remarks to the Diet in 2014, she argued that gender-based discrimination was not real and called gender equality “delusional.” 53 Sugita’s overtly neo-nationalist politics have also included the denial of Japanese war crimes as well as racially charged attacks on people of Korean descent living in Japan.54 Soon after being elected, she also emerged as a critic of pro-LGBT initiatives. In a March 2015 post on her personal website titled “My thoughts on why LGBT support policies aren’t necessary,” she argued that LGBT people in Japan did not face social discrimination and that creating policies to support them would divert governmental resources away from initiatives combating child abuse and neglect.55

Sugita reprised a similar argument in several articles written between 2016 and 2018 for the political and literary magazine Shinchō 45. Although Shinchō 45, published by Shinchōsha since 1982 and aimed at a middle-aged reading demographic, had previously focused on literature and culture rather than politics, the magazine took a conservative political and editorial turn under the direction of Wakizuki Ryōsaku, who became editor-in-chief in 2016.56 According to one Shinchōsha employee, this shift was not motivated by any ideological convictions on the part of Wakizuki but was part of a concerted strategy to raise magazine sales by appealing to right-wing readers.57 Sugita’s articles in the magazine during this period repeatedly emphasized her anti-feminist and anti-LGBT politics. In a 2016 article titled “There is no need to support something like ‘LGBT,'” for example, she argued that in light of ongoing childbirth decline, the government should focus on raising productivity (seisansei) and therefore on supporting heterosexual couples, contending that doing so was “making a distinction, not discrimination.”58

It was not until writing an article on LGBT issues for the August 2018 issue of Shinchō 45, however, that Sugita and her views became more widely known. Titled “The level of LGBT support is excessive,” (LGBT shien no do ga sugiru), the article critiqued what Sugita describes as excessive attention to LGBT issues in mainstream media. Declaring Japan to be a tolerant society, Sugita argues that LGBT discrimination is a private issue, one of “parents not understanding” their children.59 As a private matter, she states, the Japanese government has no need to use tax revenue to offer LGBT people support, and it would be a mistake to do so in the face of childbirth decline. Because same-sex couples cannot have kids, she says, they “lack productivity,” and thus should not be given financial support by the government.60 She concludes by warning against proposed initiatives to support transgender students in educational settings, arguing they would lead to “great upheaval and confusion.” 61

As previously noted, Sugita’s emphasis on productivity as a reason to oppose LGBT rights reflects earlier rhetoric espoused by the LDP. The same month her article was published, fellow LDP Lower House Representative Tanigawa Tom defended his opposition to same-sex marriage on a program for the digital channel Abema TV by describing homosexuality as “like a hobby.” 62 What was unique about Sugita’s article was not the arguments it made but rather the scale of the reaction it provoked on social media and elsewhere. Shinchō 45 published Sugita’s article on July 18, 2018 as part of a special issue criticizing the center-left newspaper Asahi Shimbun. A few days later, the article was criticized by Lower House Representative Otsuji Kanoko, a former member of the Constitutional Democratic Party (Rikkentō, hereafter CDP) and the first openly gay member elected to the Diet. On July 20, Otsuji criticized Sugita on Twitter, writing that “a public figure shouldn’t use ‘productivity’ to assess others.” 63 Otsuji’s response helped fuel an online backlash against Sugita’s article, which was widely shared on Twitter and other social networking sites. On July 23, the Twitter user and activist Hirano Taichi posted the hashtag “7/27 Protest in front of LDP headquarters seeking Representative Sugita Mio’s resignation,” calling for in-person demonstrations against Sugita’s article and other anti-LGBT rhetoric by LDP members.64 Hirano’s call to action was rapidly promoted on social media, both by individual activists as well as larger organizations including Tokyo Rainbow Pride and the Japan Alliance for LGBT Legislation (LGBT Rengō Kai).65

On July 27, more than 5,000 people gathered in front of LDP headquarters in Nagatachō, Tokyo to protest.66 The crowd ranged from longtime LGBT activists and members of opposition parties to local citizens, some protesting for the first time in their lives. A group of openly LGBT politicians called the Municipal LGBT Legislators Alliance (LGBT Jichitai Giin Renmei) delivered a joint declaration of protest to the LDP at the demonstration, stating that Sugita’s article “encourages prejudice towards LGBT people and rejects those without children, those who cannot produce children, and people in precarious economic situations as the result of disability and illness.” 67 Other speakers at the July 27 protests included a representative of Tokyo Rainbow Pride, the organization responsible for organizing Tokyo’s annual Pride parade. In a written speech, the representative emphasized the organization’s non-political nature but said that Sugita’s article had left them “speechless with anger and sadness,” and that her comments “not only erase sexual minorities, but also infringe on the rights of those without children, the elderly, the disabled, and all minorities.” 68 According to the journalist Udagawa Shii, Sugita’s framing of LGBT couples as non-productive became the “axis” upon which activist protests connected LGBT issues with those of other marginalized groups. According to him, many of the people who came to the protests were not themselves LGBT but wanted to declare their opposition to Sugita’s rhetoric based on their own understandings of productivity.69

The July protests signaled a perceptible shift for many activists. Suzuki Ken, a professor of law at Meiji University, called the protest “the first days of Japan’s revolution,” while activist Hatakeno Tomato was one of the first to describe the demonstration as “Japan’s Stonewall.” 70 Kogura Higashi, founding editor of the gay magazine Badi (1994-2019), described the protests as a “dream,” for veteran activists such as himself, who had hoped for such a movement to emerge in Japan since the 1970s.71 The protests also suggested a shift away from depoliticized, non-confrontational activism that had been previously emphasized by some groups. In an interview at the July protest, Matsunaka Gon, author of the 2015 Shibuya SSP petition and founder of the non-profit organization Good Aging Yells, which had been instrumental in the passage of the 2015 Shibuya proposal, expressed this sense of change. While emphasizing that his organization strove to be politically neutral and was dedicated to creating “positive spaces” for LGBT people, he said that events including Sugita’s article caused him to question “whether this kind of activism was really enough.” 72 While admitting he had previously felt an “aversion” to protest as a form of activism, he said that Sugita’s comments had ultimately “compelled me to raise my voice.”

The July protests were followed by protests on August 5th in cities including Tokyo, Osaka, and Fukuoka and attended by thousands of demonstrators.73 The largest of these protests was held at Shibuya Station and featured a diverse roster of speakers including activists, journalists, academics and social media personalities.74 Prior to the protests, activists circulated placard designs online taking aim at Sugita and Shinchō 45 with slogans including “Don’t discriminate using ‘productivity’,” (seisansei de sabestsu wo suru na) and “Books are for understanding,” (hon wa rikai suru tame ni). At the Shibuya protests, atop a van-elevated stage covered in rainbow-colored posters reading “FUCK YOU VERY MUCH,” speakers addressed a crowd of thousands, sharing a variety of perspectives on both Sugita’s comments and the potential for the protests to foster new modes of solidarity. The journalist Udagawa Shii implored the protesters to continue to fight against discrimination, declaring “Women, LGBT people, disabled people, Zainichi people, all those discriminated against and all those who can’t abide discrimination, let us raise our voices together in solidarity!” 75 Other speakers such as Kitamaru Yuji made this call for intersectional activism even more explicit, declaring in his speech that “I am gay. I am lesbian. I am bisexual. I am queer. I am trans. I am elderly. I am a child. I am a woman. I have no productivity, and what of it?” 76 The YouTuber and educator Suzuki Natose eloquently summed up this sense of solidarity in her August 5th speech, saying that the protestors came together to jointly declare that they “did not live for the sake of productivity.” 77

The 2018 protests, organized largely online by a loose coalition of activists and LGBT groups, represented a unique moment for LGBT politics in Japan. They emerged as a spontaneous collective response to a conception of productivity articulated by conservative politicians and intellectuals since the 1990s. Although Sugita’s article was directed at LGBT couples, it was criticized broadly by disability activists, feminists, and others who linked her rhetoric to eugenicist thought (yūsei shisō).78 On August 7th, a group of activists associated with the disability rights organization Living Group (Ikiteiku Kai) held a press conference denouncing Sugita’s article as discriminatory, linking her rhetoric to ongoing attacks on the nation’s welfare system.79 On August 19th, feminists in Kyoto organized smaller-scale protests that linked Sugita’s comments to recent revelations that Tokyo Medical University had systematically discriminated against women in its admissions process.80

The political theorist Okano Yayo writes that it was precisely Sugita’s emphasis on productivity as a metric of social value that allowed individuals from diverse social backgrounds and experiences to understand her attacks on LGBT couples as broadly discriminatory.

According to Okano, the article ironically served as “a tool to make people more aware of the crisis at the heart of Japanese politics,” represented by the ideological conception of productivity.81 This assessment is echoed by the disability activist Kumagaya Shinichirō, who argued that there are two possible responses to judgements about productivity like Sugita’s: to argue that one is indeed productive, and thereby legitimize the terms of the judgement, or to instead critique the “fundamental root,” of the issue, i.e. the concept of productivity itself.82 In this context, the 2018 protests suggest the emergence of a new form of political mobilization linking feminist, queer, and disabled activists via a shared criticism of ideological notions of productivity.

Conclusion

While it is too soon to give a thorough assessment of the legacy of the 2018 protests, a few developments bear mentioning. While the LDP released a statement in late July distancing itself from Sugita, saying her comments represented her personal opinions, the editors of Shinchō 45 doubled down, publishing a September issue defending Sugita that asked, “Were Sugita Mio’s comments really so ridiculous?” One of the most incendiary articles was written by the literary critic Ogawa Eitarō, who argued that promoting LGBT rights was akin to promoting rights for sexual harassers.83 The issue was denounced by numerous former contributors to the magazine and was described as an embarrassment by employees at its publishing company, Shinchōsha. In response to the controversy, the magazine’s board of directors apologized for using “bigoted expressions” and announced they would cease publication indefinitely.84

Although Sugita herself initially refused to apologize for her comments, in April 2019 she participated in a TV program with fellow LDP member Inada Tomomi and a small group of LGBT activists in Tokyo’s historically gay Ni-Chōme neighborhood. During their discussion, Sugita apologized to the activists, calling her previous words “inappropriate.” 85 Her contrition drew mixed reactions from the activists themselves: some, such as the organization Tokyo Rainbow Pride, announced that they accepted the apology. Others, however, called her apology too little too late, and criticized groups that had ‘accepted’ it on behalf of all sexual minorities.86

Since the 2018 protests, the political situation for LGBT people has changed significantly in Japan. Same-sex partnership systems have proliferated in municipalities and prefectures across the country since 2019. As of April 2021, more than 100 municipalities have adopted same-sex partnership systems.87 In July 2019, CDP member Ishikawa Taiga won a seat in the Upper House of the Diet after running a campaign emphasizing his gay identity and linking his experiences to efforts to promote diversity in society. The 2019 elections also saw another, subtler landmark; for the first time, every major political party, including the LDP, included language in its campaign manifesto (kōyaku) affirming sexual minorities.88 Finally, in March 2021 the Sapporo District Court made a groundbreaking ruling, calling the government’s failure to recognize same-sex marriage unconstitutional.89

Despite this ruling, however, the legal situation for same-sex marriage nationwide has not yet changed. And while progress has been made at the municipal and regional levels, efforts to legalize same-sex marriage and adoption rights at the national level remain stalled, and transgender individuals continue to face extraordinary legal and social difficulties.90 In early 2021, it appeared that the LDP’s LGBT Comprehension-Raising Bill, first proposed in 2016, was gaining traction once again after having been shelved in 2018. In March, then-Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide determined that the bill fell under the jurisdiction of the Cabinet and tasked his minister Sakamoto Tetsushi with managing the bill’s introduction to the Diet.91 In April 2021 the LDP SOGI Committee began work on finalizing the language and content of the bill. During the same month, a new, intraparty working group was formed within the Diet to negotiate the language of the bill between the LDP and opposition parties. The intraparty group was headed by Inada on the LDP side and Nishimura Chinami of the Constitutional Democratic Party representing the opposition. On May 10, the intraparty group announced that it had agreed upon the language for a revised version of the bill.92

Opposition to the bill soon began to build amongst conservatives inside and outside of the LDP. Much of their opposition centered around the language of the bill, in particular its use of the term “gender identity,” (sei jinin) and its description of discrimination as “unacceptable,” (yurusanai). The use of the term gender identity was attacked by legislators Yamatani Eriko and Shigeuchi Kōji, a representative for the LDP-aligned LGBT Awareness Raising Group, who charged that it sought to legitimize transgender identities they deemed ‘threats’ to women. In March, Shigeuchi addressed the LDP Subcommittee for the Advancement of Women in the Diet, giving a speech titled “LGBT out of control” centered on what he described as the threat transgender women posed towards cisgender women.93 His speech was supported by Yamatani, who on May 13 gave her own speech warning of the ‘threat’ of transgender athletes and other forms of LGBT identity that she said would be legitimized by the bill.94

The clause declaring discrimination ‘unacceptable’ was also a sustained target of criticism by conservatives, particularly Yagi Hidetsugu, who characterized it as overly ambiguous and a potential mechanism for inviting legal action to punish or prohibit any speech deemed “discriminatory.” In a memo distributed amongst conservative legislators, he argued that the language could be used not only to limit free speech, but ultimately compel the state to treat same-sex and opposite-sex couples “equally,” an outcome he warned could lead to the legal legitimization of self-chosen gender identity and the endangerment of women.95 Former Prime Minister Abe himself requested that the SOGI Committee change the language to make it less direct. The committee acceded to the request, changing the language from “Discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity is unacceptable,” to “There should be no inappropriate discrimination or prejudice towards sexual minorities.” 96 Despite their reticence, the opposition parties agreed to these and other modifications to the bill in the following days, determining that passing something was preferable to passing nothing at all.

At an internal party meeting to discuss the proposed bill on May 20, tensions within the LDP over its scope and language came to a head. During the meeting, several conservatives spoke out against the proposed bill in blunt and derogatory language. Yamatani continued to tie the bill to the specter of transgender women entering women’s bathrooms and participating in women’s sports; lower-house member Nishida Shoji also spoke out against the bill, saying that the concept of “LGBT,” was “morally unacceptable.” 97 Former transportation minister Yana Kazuo arguably went further than either of his colleagues in his comments during the meeting, implying that LGBT people were biologically deficient and that a society where this couldn’t be stated aloud was “absurd.” 98 Ultimately, the language of the bill was agreed upon on May 24th, yet at that point the bill’s future was already in doubt; finally, on May 28, the bill was sent to the LDP’s Policy Committee where responsibility for it was delegated to the LDP’s Chief Secretary, Chairman, and Policy Chief, who decided to shelve the bill. While the official reasoning given for this was that the party could not find time in the Diet Committee’s annual calendar, it was also clearly a response to hardened conservative opposition within the LDP.99

With the shelving of the LDP’s Comprehension-Raising Bill, the legal and political future for LGBT people in Japan remains in doubt. Yet the legacy of the protests and their influence can still be seen in responses to LDP intransigence. On May 30, 2021, LGBT activists responded to comments made at the LDP’s internal meeting by once more holding protests at the party’s headquarters. Organized online using the hashtag “Don’t run away, LDP,” (nigeruna Jimintō), the protesters called on the LDP to listen to LGBT people and “create a law to protect [LGBT] lives,” (inochi o mamoru hōritsu wo tsukutte kudasai).100 These demonstrations echoed and built upon the strategies of the 2018 protests, which successfully challenged dominant framings of LGBT people articulated by conservatives since the 2000s and shifted mainstream debates towards interrogating the meaning of productivity itself. It is further notable that, according to one account, Abe was particularly incensed that Yana’s comments had been leaked, comparing them directly to what he called the “Sugita Mio problem” of 2018.101 It seems from these responses that the memory and influence of the 2018 protests remains strong for both activists and opponents of LGBT rights in Japan. The demonstrations from that summer have forced politicians to confront issues regarding LGBT rights that many would have otherwise dismissed or ignored. In this sense, while comparisons of the 2018 protests to Stonewall are in many ways anachronistic, they may ultimately become more resonant than they now seem.

Notes

Udagawa Shii. “We Shall Overcome: kussata sekai o koroshite sono shikabane o norikoete iku tame ni,” [We Shall Over Come: To Kill A Rotten World and Overcome Its Corpse]. Over Vol. 1, May 2019, p. 2-3; Matsuoka Sōshi, “’Watashitachi wa mō damaranai,’ LGBT o meguru 2018 nen no shakai no ugoki o furikaeru,” [We can no longer be silent: looking back at LGBT social changes in 2018] Fair-Fair, December 12, 2018

See Ioana Fotache, “Japanese ‘LGBT Boom’ Discourse and Its Discontents.” Sexuality and Translation in World Politics, edited by Caroline Cottet and Manuela Lavinas Picq (Bristol UK: E-International Relations, 2019) 27-41; Wakamatsu Takashi. “LGBT Konjaku: 1990 nendai gei būmu saikō,” LGBT [LGBT then and now: reconsidering the gay boom of the 1990s] In Aichi Shukutoku Daigaku Ronshū Kōryū Bunkagaku Hen No. 8, March 2018, pp. 115-127; Okada Kei, “Fukanzen ni ‘kuia’: seiteki shōsūsha o meguru aidentitei/bunka no seiji to LGBT no ‘seisansei’ gensetsu ga motarashita mono,” [Imperfectly ‘queer’: what the discourse surrounding LGBT ‘productivity’ and the cultural politics of sexual minority identity has shown] The Annual Review of Cultural Studies Vol. 7 (2019) 7-26.

Dentsū Diversity Lab. “Dentsū Daibashitei Rabo ga “LGBT chōsa 2018” o jissen: LGBT sō ni gaitō suru hito wa 8.9%, ‘LGBT’ to iu shintōritsu wa yaku 7 wari ni,” [Implenting Dentsu Diversity Lab’s 2018 LGBT Survey,” Those who include themselves in ‘LGBT’ is 8.9%, the word ‘LGBT’ now known by approximately 70%] January 10, 2019: 1; 2.

Shūkan Daiyomondo. “‘LGBT shijō’ o senryaku se yo! [Let’s Conquer the 5.7 Trillion Yen Domestic ‘LGBT Market’!]. February 25, 2013.

Yoshino Taichirō. “Shibuya ku, dōsei pātonā jōrei, kugikai honkaigi de kaketsu/seiritsu,” [Shibuya Ward Same-Sex Partnership Ordinance Passed And Established at Municipal Assembly Deliberative Meeting] Huffington Post Japan, March 30, 2015

See Taniguchi Hiroyuki. “‘Dōseikon’ wa kokka no gimu ka,” [Is ‘same sex marriage’ a duty of the state?] Gendai Shisō 43(16) October 2015, pp. 46-59.

Human Rights First. “IOC Adopts Proposal to Include Sexual Orientation in Olympic Charter’s Non-discrimination Principle,” December 08, 2014

Nikaidō Yuki. “Seiji no genba kara,” [From the arena of politics] in Sei no arikata no tayōsei: hitori hitori no sekushuariti ga taisetsu ni sareru shakai o mezashite [The diversity of sexuality: towards a society in which all individual sexualities are respected], edited by Ninomiya Shūhei (Tokyo: Nihon Hihyōsha, 2017) pp. 72-93: 75.

Inada Tomomi. LGBT: Subete no hito ni chansu ga ataerareru shakai wo [LGBT: Towards a Society Where all People are Given a Chance] Huffington Post Japan, December 11, 2015

Buzzap! “LGBT wa shakai o midasu” Shibuya de han dōseiai demo hassei, jimintō mo dōseikon ni kenen ni hyōmei shi, nichōme no geibā wa tekihatsu kyōka,” [“LGBT causes social chaos” An anti-gay protest emerges at Shibuya, while the LDP expresses its unease with same-sex marriage and increased restrictions on gay bars in Ni-Chōme] March 10, 2015

Yagi Hidetsugu. “Shibuya dōsei kappuru jōrei…sen’eika shita jendā furī Meiji Jingu ga ‘doseikon no seichi’ ni naru hi,” [Shibuya Same-Sex Partnership Ordinance…the day radicalized gender free Meiji Jingu becomes a ‘holy ground for same-sex marriage.’] Seiron 521, May 2015, 226-233.

J-Cast News. “Dōseikon ga shōshika ni hakusha kakeru’ giin no TV hatsugen, takoku no rei de wa dō na no ka,” [‘Same-sex marriage will spur population decline’ a representative’s TV comments, what about the examples of other countries]. March 6, 2015.

Shimbun Akahata. “LGBT sabetsu kaishō he: 4 yatō ga hōan o kyōdō teishutsu ,” [Towards the elimination of LGBT discrimination: 4 opposition parties jointly submit a bill] May 28, 2016. The parties that proposed the bill were the Japanese Communist Party, Democratic Party, Social Democratic Party, and People’s Life Party (now defunct).

Liberal Democratic Party Policy Research Committee. “Seiteki shikō/sei dōitsusei (sei jinin) no tayōsei tte? Jimintō no kangaekata [What is sexual preference/gender identity diversity? The LDP’s standpoint].” June 28, 2016, 2.

For example, the Abe government has provided material support for a variety of schemes to boost childbirth rates including sponsoring marriage-partner finding events (konkatsu), child-parent learning seminars designed to instill ‘proper maternal and paternal roles’ in new parents, and tax subsidies for newlywed couples and ‘traditional’ three-generation households. For more information, see Saitō Masami, “Bakkurashu to kansei konkatsu no renzokusei,” [The continuity of the backlash and government-sponsored marriage activities.] in Maboroshi no ‘nihonteki kazoku’ [The illusionary Japanese family], edited by Hayakawa Tadanori (Tokyo: Seikyūsha, 2018), pp. 79-116; Horiuchi Kyōko, “Zeisei to kyoiku wo tsunagu mono,” [That which connects the tax system and education] ibid., 117-140.

Nikkei Keizai Shimbun. “Shushō ‘Seisansei/hito zukuri ryōrin’ dai yon ji Abe naikaku hassoku,” [Prime Minister: ‘The twin wheels of productivity and human development’ the 4th Abe Cabinet Commences]. November 1, 2017

Asahi Shimbun. “Abe Shushō no shisei hōshin enzetsu (zenbun),” [Full text of Prime Minister Abe’s Policy Speech]. January 23, 2018: p. 5.

Tomiko Yoda. “A Roadmap to Millennial Japan.” In Japan after Japan: Social and Cultural Life from the Recessionary 1990s to the Present, edited by Tomiko Yoda and Harry Harootunian (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006) pp. 16-54.

Inoue Teruko. “Bakkurashu ni yoru seibetsu nigensei ideorogi saikōchiku,” [The reconstruction of gender binary ideology by the backlash] Joseigaku Vol. 15 (2007) 14-22: 15-16.

Tomomi Yamaguchi. “‘Gender Free,’ Feminism in Japan: A Story of Mainstreaming and Backlash,” Feminist Studies, Vol. 40, No. 3 (2014), pp. 541-572; see also Ayako Kano. Japanese Feminist Debates: A Century of Contention on Sex, Love, and Labor (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2016), 140-172.

Tomomi Yamaguchi. “‘jendā furī’ ronsō to feminizumu undō no ushiwareta jūnen,” [The ‘gender-free’ controversy and the decade feminist activism lost] Bakkurashu! Naze jendā furī wa tatakareta no ka [Backlash! Why was gender free attacked?] (Tokyo: Sōfūsha, 2006) 244-282: 264-6.

Kazama Takashi, “‘Chūsei ningen,” to wa dare ka? Seiteki mainoritei he no ‘fobia’ wo fumaeta teikō he,” Who is the ‘gender neutral human’? Towards a resistance against phobias towards sexual minorities.] Joseigaku 15 (2007) 23-33: 23.

Shimizu, Akiko. “‘Imported” Feminism and ‘Indigenous’ Queerness: From Backlash to Transphobic Feminism in Transnational Japanese Context,” Jendā Kenkyū, No. 23, 2020 pp. 89-104: 92.

Shimizu, Akiko. “Scandalous equivocation: a note on the politics of queer self‐naming.” Inter‐Asia Cultural Studies, 8:4 (2007) 503-516: 504.

Horie, Rezubian, 196-7; see also Kazama Takashi. “Dōseiai no jinken to gurōbaru ka: Tokyo to jinken shishin kosshi kara no sakujo o megutte,” [Globalization and homosexual human rights: on the deletion of the Tokyo Metropolitan Human Rights charter proposal Gendai Shisō 28 (2), October 2000, pp 94-99; Yomiuri Shimbun. “Seidōitsusei shōgaisha no jinken mamoru: Yame shi, danjo sankaku jōreian o kaketsu,” [Protecting the human rights of those with GID: Yame city passes DKS ordinance proposal] March 22, 2004.

Nishio Kanji and Yagi Hidetsugu. Shin kokumin no yudan: ‘jendā furī’ ‘kageki na seikyōiku’ ga nihon wo horobosu [The new issue citizens are unprepared for: ‘Gender free’ ‘radical sex education’ will destroy Japan] (Tokyo: PHP Kenkyūsho, 2005): 301. The term ‘okama’ is a derogatory term used to describe gay and effeminate men. While some individuals have attempted to reclaim the term to describe themselves, many consider it offensive, and debates over the usage of the term in the public domain have been extensive. See Fushimi Noriaki et al.,’Okama’ wa sabetsu ka: shūkan kinyōbi no ‘sabetsu hyōgen’ jiken (Tokyo: Potto Shuppan, 2002).

Oguie Chiki. “Seiken yotō no bakkurasshu,” [The backlash of the ruling party and administration]. In Bakkurashu! Naze jendā furī wa tatakareta no ka [Backlash! Why was gender free attacked?] (Tokyo: Sōfūsha, 2006) 357-367: 357-8.

Gender Cabinet Equality Office. “Jimintō kageki na sei kyōiku/jendā furī kyōiku jittai chōsa purojekuto chimu kaigō (7 gatsu 7 nichi) teishutsu shiryō,” [LDP team for investigating the state of radical sex education and gender free education July 7 informational materials] July 7, 2005.

Abe Shinzō. Utsukushii kuni e [Towards a beautiful country] (Tokyo: Bungei Shunju, 2005) p. 316-317.

Yokō Toshinari. “Chihō jichitai no seisaku tenkan ni okeru SNS o mochiita shakai undō no furēmingu kōka: Shibuya ku ‘dōseiai pātonāshippu jōrei’ no seitei katei o jirei ni,” [The Framing Effect of Social Movement Using SNS in Policy Change of Local Government-Based on the Case of the Policy Making Process on Shibuya City’s “Same-Sex Partnership Ordinance”] Annual Review of the Institute for Advanced Social Research Vol. 16, March 2019, 1-16.

Kawasaka also notes that the ordinance places burdens on same-sex couples not placed on opposite-sex couples, including the requirement that their partnership not be “against public order and decency,” (Kōjo ryōzoku ni han shinai kagiri). See Kawasaka. Jinken’ ka ‘tokken’ ka ‘onkei’ ka, 91-2.

Akitomo Shingae. “Daibashitei suishin to LGBT/SOGI no yukue: Ichijou ka sareru shakai undou,” [Diversity promotion and LGBT/SOGI: the marketization of social activism] in Tayōsei to no taiwa: Daibashitei suishin ga mienakusuru mono [A Debate with Diversity: What Diversity Promotion Obscures] edited by Iwabuchi Kōichi (Tokyo: Seikyūsha, 2021) 37.

Lisa Duggan. The Twilight of Equality? Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics, and the Attack on Democracy (Boston MA: Beacon Press Books, 2003): 50.

Myrl Beam. “What’s love got to do with it? Queer politics and the ‘love pivot’,” in Queer Activism After Marriage Equality, edited by Joseph Nicholas DeFilippis, Michael W. Yarbrough, and Angela Jones (New York: Routledge, 2018) pp. 53-60: 59.

KIRA and Esumureruda. Dōsei pattonashippu shōmei, hajimarimashita [Same-Sex Partnership Certificates Have Begun] (Tokyo: Potto Shuppan, 2015) 27.

Matsunaka Gon. “Shibuya ouen! Minna ni yasashii Nihon wo mezashite, ‘dōsei pattonashippu shōmeisho’ wo jitsugen shitekudasai! Let’s take action and make a change starting from Shibuya! ‘Same-sex partnership certificate,’” Change.org, February 18, 2015. Accessed August 1, 2021.

Hasebe has not only described LGBT people as uniquely creative, but also as assets indispensable to making Shibuya a ‘cool town’ (kakkoii machi) as well as an ‘international city’ (Kokusai toshi); see Dōsei pattonashippu shōmei, hajimarimashita, 28-29; 30.

Shimizu Akiko. “Yōkoso, gei furendori na machi he: supesu to sekushuaru mainoretei,” [Welcome to a Gay-Friendly City: Space and Sexual Minorities] Gendai Shisō 43(16) October 2015, pp. 144-155; See also Noah McCormack and Kohei Kawabata, “Inclusion and Exclusion in Neoliberalizing Japan,” Cultural and Social Division in Contemporary Japan: Rethinking Discourses of Inclusion and Exclusion, edited by Yoshikazu Shiobara, Kohei Kawabata and Joel Matthews (New York: Routledge, 2020) pp. 24-51: 38-41.

Dai 187 kai kokkai shūgiin honkaigi dai 9 gō Heisei 26 nen 10 gatsu 31 nichi [Minutes of the 187th Session of the House of Representatives of the Diet, Volume 9], October 31, 2014 p. 11.

Mark Ealey and Satoko Oka Normitsu. “Japan’s Far-right Politicians, Hate Speech and Historical Denial – Branding Okinawa as ‘Anti-Japan.'” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Volume 16, Issue 3, Number 2, February 1, 2018

Sugita Mio. “LGBT shiensaku ga hitsuyō de nai riyū watashi no kangae,” [The reason LGBT support policies aren’t necessary: my thoughts] Ameba Blog, March 26, 2015.

Asahi Shimbun. “Henshūchou ga ‘bōsō’ shi shimen kagekika Shinchō 45 no jōren hissha shiteki,” [Shinchō 45’s regular contributors identify the editor-in-chief as acting recklessly and radicalizing [the] magazine]. September 9, 2018

Litera. “‘Shinchō 45’ Kyūkan seimei no uso! Sugita Mio yōgō, LGBT sabetsu wa ‘henshūbu’ de naku ‘torishimaruyaku’ ga GO wo dashiteita,” [Shinchō 45’s ‘ceasing publication’ lie! Sugita Mio’s defense and LGBT discrimination were given the go-ahead not by the editorial board, but by the board of directors] Last updated September 26, 2018

Sugita Mio. “’LGBT’ shien nanka iranai,” [There is no need to support something like ‘LGBT’] Shinchō 45 35 (11), November 2016, pp. 58-61.

Sugita Mio. “LGBT shien no do ga sugiru,” [The level of LGBT support is excessive]. Shinchō 45 37 (8) August 2018, pp. 57-60: 58.

Asahi Shimbun. “Dōseikon “shumi mitai na mono,” netto bangumi de jimin Tanigawa shi,” [LDP Representative Tanigawa on Internet Program: Homosexuality is “something like a hobby”] August 1, 2018

Udagawa Shii. “Sugita Mio giin no ‘sabetsu hatsugen’ ni kōgi suru demo ni, naze 5000 nin mo atsumatta no ka: sekushuaru mainoriti igai ni mo hirogatta rentai no wa,” [Why did up to 5000 people come to protest Representative Sugita Mio’s ‘discriminatory comments’ the ring of solidarity expanded beyond sexual minorities] Huffington Post Japan, July 29, 2018

LGBT Rengō Kai [Japan Alliance for LGBT Legislation]. “Shūgi giin Sugita Mio shi no ronkō ” ‘LGBT’ shien no do ga sugiru’ ni taisuru kōgi hyōmei,” [Declaration of Protest to House of Representatives Member Sugita Mio’s article “The level of LGBT support is excessive”]. July 23, 2018

Nikkan Sports. “‘Sabetsu wo suru na’ Sugita Mio shi no jinin motome daikibo demo [Don’t discriminate: Large scale protests call for Sugita Mio’s resignation]. July 27, 2018

Tokyo Rainbow Pride. “#0727 Sugita Mio no giin jinin o motomeru jimintō honbu mae kōgi de no supichī no zenbun o keisai shimasu [Publishing the speech given at the 0727 protests in front of LDP headquarters calling for Sugita Mio’s resignation in their entirety] Accessed December 13, 2020.

Gōto Junichi. “Sugita Mio mondai 2: ‘Nihon no Sutōnwōru to natta kōgi shūkai’ [Sugita Mio problem 2: The protest assembly that became ‘Japan’s Stonewall’ GladXX; Matsuoka Sōshi, “‘Watashitachi wa mou damaranai,’ LGBT wo meguru 2018 nen no shakai no ugoki wo furikaeru [“We can’t be silent”: looking back at the social changes for LGBT in 2018] Fair, December 30, 2018. Accessed December 13, 2020.

Asahi Shimbun. “Sugita Mio giin no hatsugen ‘sabetsu da’ ‘mazu shazai wo’ kōgi demo,” [“It’s discrimination,” “First, apologize,” demonstration against Representative Sugita Mio’s comments] August 5, 2018

The River. “2018.08.05 ‘#0805 Sugita Mio giin no sabetsu hatsugen ni kōgi suru Shibuya hachikō mae gaisen: Utagawa Shii san (furīransu/editā/raitā) [#0805 Protests at Hachiko, Shibuya against Representative Sugita Mio’s discriminatory comments]: Utagawa Shii (Freelance editor/writer) 2018.08.05.” YouTube Video, 7:05. August 5, 2018.

The River. “2018.08.05′ #0805 Sugita Mio giin no sabetsu hatsugen ni kōgi suru Shibuya hachikō mae gaisen: Kitamura Yūji san (jānarisuto/koramunisuto) 8/11.” [#0805 Protests at Hachiko, Shibuya against Representative Sugita Mio’s discriminatory comments: Kitamura Yūji san (Journalist, columnist)]. YouTube Video, 10:10, August 5, 2018

Mainichi Shimbun. ” ‘Seisansei ga nai’ wa Nachi no yūsei shisō shikishara hihan kaigai medeia mo hōdō [They lack productivity is Nazi eugenicist thought: criticism from intellectuals, also reported in overseas media] July 28, 2018 (Updated July 28, 2018).

Tanaka Satoko. “Sugita shi no ‘seisansei nai’ ni kōgi hyōmei shōgaisha ya nanbyō kanja ra [Declaration of protest by disabled people and people with intractable illnesses against Sugita’s ‘no productivity’ comments] Asahi Shimbun Digital, August 7, 2018

IWJ Independent Web Journal. “Ikari no onna demo 8/19 Kyoto,” [Women’s anger demonstration in Kyoto, August 19] August 19, 2018

LGBT Rikai Zōshin Kai [Association for Raising LGBT Understanding]. “‘Kinkyū hyōmei’ Sugita Mio shūgiin giin no keisai kiji ni taishite [Declaration of emergency: on Lower House Representative Sugita Mio’s article] Hatena Blog, July 23, 2018.

Okano Yayo. “Sabetsu hatsugen to, seijiteki bumyaku no jūyōsei: ‘LGBT shien no do ga sugiru’ no konkan,” [Discriminatory comments and the importance of political context: the foundation of ‘The level of LGBT support is excessive] Sekai Vol. 913 (September 2018) pp. 140-9: 141; see also “Sabetsu ga sabetsu to ninshiki sarenai kuni ni ikiteite,” [Living in a country that doesn’t recognize discrimination as discrimination] Ovā Vol. 2 (January 2020) p. 6-17.

Iwanaga Naoko. “‘Seisansei’ to wa nani ka? Sugita giin no kataru koto to, shōgaisha undo no motometekita koto Kumagaya Shinichirō intabyū [What is ‘productivity’? What Representative Sugita discusses and what the disabled seek; an interview with Kumagaya Shinichiro.] Buzzfeed News Japan, September 26, 2018

Ogawa Eitarō. “Seiji wa ‘ikizurasa’ to iu shukan o sukuenai,” [The government cannot save you from the objective ‘pain of life’]. Shinchō 45 Vol. 39, October 2018, 84-89.

Harimaya Takumi. “Shinchō 45 mondai ni tsuite geneki shain ni kiita ‘henshūbu wa mōsei o’ ‘saiaku no shuppan datta’ [I asked current employees about the Shinchō 45 problem – ‘the editorial department should reflect,’ ‘the worst publication’.] Buzzfeed News Japan, September 23, 2018

Abema News Channel. “Dokusen! Sugita Mio giin to Inada Tomomi giin ga Shinjuku Ni-Chōme de LGBT no minasan to taidan,” [Exclusive! Representatives Sugita Mio and Inada Tomomi have a face to face conversation with LGBT people at Shinjuku Ni-Chōme] April 28, 2019,

See Hatakeno Tomato. “Tokyo Reinbō Puraido Chokuzen! “Seisansei o hatsugen o wasurete wa ikenai,” [Standing before Tokyo Rainbow Pride! We can’t forget those comments about productivity] April 27, 2019

Yamaga Saya. Dōnyū jichitai wa 100 koe! ‘Dōsei pātonāshippu seido’ no ima [More than 100 municipalities have introduced them! The current state of ‘same sex partnership systems’]. Cosmopolitan Japan, April 9, 2021; See also Nijiro Diversity, “Chihō jichitai no patonashippu seido tōroku kensū” [The number of recorded regional municipal same-sex partnership systems] April 16, 2021

Nippon Hōsō Kyōkai. “Kakutō no kōyaku,” [2019 Campaign manifestos of each party] Undated, https://www.nhk.or.jp/senkyo/database/kouyaku/2019/seisaku/08.html Accessed August 1, 2021.

The Japan Times. “Japan court rules failure to recognize same-sex marriage unconstitutional.” March 17, 2021 https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/03/17/national/crime-legal/same-sex-marriage-landmark-ruling/

Alex Bollinger. “Japan’s Supreme Court Rules in Favor of Forced Sterilization of Trans People.” LGBTQ Nation, January 25, 2019, https://www.lgbtqnation.com/2019/01/japans-supreme-court-rules-favor-forced-sterilization-trans-people/

Matusoka Sōshi. “Jimintō ga teian shi mizukara tsubushita ‘LGBT shinhō’ wo meguru ‘6 nenkan no keii’,” [The ‘6-year long process’ by which the LDP proposed and destroyed its own ‘New LGBT bill’]. Gendai Bijinesu, June 15, 2021, https://gendai.ismedia.jp/articles/-/84156?imp=0, 3.

Nikaidō Yuki. “Kore wa sensō, de wa nai: LGBT rikai zōshin hōan miokuri,” [This, is not war: the shelving of the LGBT Awareness Raising Bill]. Sekai, August 2021, pp. 10-15: 12.

Ibuki Saori. “‘Inochi o mamoru hōritsu wo tsukutte kudaisai’: Jimintō giin no sabetsu hatsugen, ima tōjisha tachi gai tsutaetai omoi [‘Please make a law that protects life’: The thoughts that LGBT people want to express regarding LDP members’ discriminatory comments] Buzzfeed Japan, May 30, 2021