Abstract: The current Hong Kong situation is the product of a long-term accumulation of crises and the consequences of the broader interplay of clashes among nations. Taiwan has long seen the PRC’s treatment of Hong Kong as a barometer of its Taiwan policy. The “One Country, Two Systems” formula was proposed with an eye on Taiwan. In recent years, Beijing seemed to decouple the Hong Kong-Taiwan nexus as it began to turn the screws on Hong Kong. Taiwan has played a significant but often misunderstood role in Hong Kong’s resistance to Chinese domination. This article explores the political impact of the Hong Kong-Taiwan civil society nexus from the early 2010s, through the Umbrella Movement (2014), to the Anti-Extradition Movement (2019) and the implementation of the National Security Law (2020). The ever-more repressive measures China imposed on both Hong Kong and Taiwan have given rise to close and lively exchanges between both civil societies. Taiwan may play a supporting role in Hong Kong’s resistance to Chinese repression and subordination.

Keywords: Contentious politics, repression, resistance movements, Hong Kong, Taiwan, China

Taiwan has long seen the PRC’s treatment of Hong Kong as a barometer of its Taiwan policy. When Deng Xiaoping proposed the “One Country, Two Systems” formula four decades ago, he was eyeing Taiwan, though without a timetable. As Beijing started turning the screws on Hong Kong in recent years, it seemed to decouple the Hong Kong-Taiwan nexus. This article explores the other side of the Hong Kong-Taiwan nexus—inter-civil society engagement and its political impact.

The uneasy post-Cold War partnership between Taiwan and Hong Kong has undergone a profound transformation in recent years. Economically, Hong Kong has been a central operations center for Taiwanese enterprises dealing with China since the late 1980s. When Taiwan and China launched direct flights in 2008, Hong Kong’s status as an entrepôt diminished, but it continues to play a vital function for Taiwan. More salient changes took place in the political sphere. Taipei maintained an “unofficial relationship” with Hong Kong as a British colony. After the handover of Hong Kong’s sovereignty to the PRC in 1997, Taipei continued to maintain Hong Kong’s special status through its “Laws and Regulations Regarding Hong Kong and Macao Affairs” (enacted in March 1997).

The US canceled its similar preferential customs status for Hong Kong in 2020 after crackdowns on protesters and mass arrests indicated that the PRC was reneging on its commitment to the “One Country, Two Systems” policy. The US Congress hurriedly enacted laws aimed at enhancing human rights protections for Hongkongers and imposing sanctions on Chinese and Hong Kong officials. This development has subtly affected Taiwan’s Hong Kong policy. Lacking the US government’s political clout, the Taiwanese government offers low-profile humanitarian aid to Hong Kong exiles through civic groups or joint efforts with NGOs. The estrangement between Taiwan and Hong Kong at the government level has gone hand-in-hand with closer civil society ties. This reflects heightened US-China rivalry amid significant geopolitical changes in the region.

Hong Kong’s Civil Movement and Interaction with Taiwan Since 2012

2012 was the critical year when the civil societies of both polities started interacting closely.1 Beijing had been doubling down on its efforts to influence Taiwan’s mainland policy during the intervening period, but the Taiwanese were either unaware of or indifferent to such influence. Various pro-China media acted as Beijing’s loudspeakers, with the Want Want Group particularly brazen in actively acquiring media outlets and fulfilling its “united-front” assignment by the Chinese government. University students and NGO activists eventually took to the streets against that “media monster” in what was a harbinger of the 2014 Sunflower Occupy Movement. At that point, fighting the “China factor” became a slogan in the “anti-media monster” movement.

The “anti-patriotic education movement” erupted in Hong Kong that same year in response to Beijing’s efforts to enhance its political influence in schools. A hunger strike by a group of Hong Kong high school students called Scholarism drew the attention of Taiwanese activists. Taiwanese students created a Facebook page to share Scholarism’s activities and express support for “Hong Kong’s anti-brainwashing education movement.”2 Journalists and activists raised awareness of the campaign in Taiwan’s civil society. With both sides feeling the heat of China’s impact, civic groups from Taiwan and Hong Kong began engaging with each other through increasingly frequent visits, interviews, workshops, and conferences. Worried by these exchanges, Beijing and its Hong Kong-based proxies made preemptive moves.

China has long nurtured a deep fear of Western infringement of its sovereignty, born of historical experience. The witch-hunt for “separatism” has become routine. As early as 2010, Beijing, without any reasonable evidence, accused a radical wing of the democracy movement, which was proposing a quasi-referendum campaign, of attempting to manufacture a public climate for independence.3 The incident revealed China’s self-imposed fear of separatism. In 2013, a trade union leader and several democracy advocates were accused of “merging Hong Kong independence with Taiwan independence” by a pro-China newspaper after participating in a conference in Taiwan.4 The accused had never in fact advocated independence. Echoing previous warnings targeting the Dalai Lama’s visit to Taiwan and the release of a documentary on Xinjiang exile Rebiya Kadeer,5 pro-Beijing newspapers accused activists in both Hong Kong and Taiwan of “an act of secession, intended to lead the ‘Occupy Central’ movement in the direction of ‘Hong Kong independence’ and challenge the ‘one country’ principle.”6 “The people of Hong Kong, the SAR (Hong Kong) Government and the Central Government… need to deal with it strongly and promptly.”7

So-called “Hong Kong independence” was nearly unheard of in the pan-democratic camp at that time, but Beijing’s paranoid attacks added fuel to the fire and became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Before the localist turn in the 2010s, Hong Kong’s democratic parties had primarily taken Chinese nationalism for granted. They had long supported or acquiesced in Beijing’s irredentist agenda toward Taiwan. The Legislative Council (LegCo), for instance, passed a motion “opposing Taiwan becoming independent” on the eve of the swearing in as president in 2000 of Chen Shui-bian of the opposition Democratic Progressive Party. Most opposition legislators approved the motion, even though it had been initiated by the pro-Beijing establishment party. Of the twenty pan-democrat legislators, twelve voted for the motion; one abstained; seven walked out of the chamber before the call to vote.8 For the pan-democrats, independence was taboo for either Hong Kong or Taiwan. The bottom line was supporting “peaceful unification” and opposing the use of force to take back Taiwan. In the debate, a key democratic legislator argued that

If Taiwan has the right to self-determination, what about Tibet? What about Xinjiang? What about Guangxi? What about Inner Mongolia? What about Gaoxiong in Taiwan? What about Yilan? What about Penghu and Mazu? This is an extremely complicated issue, thus, no one will say that as Taiwan is a people and has its special history, it has the right to self-determination because this cannot be justified.9

The public transcript of the debate indicates the democrats’ political outlook on Taiwan. It also reveals Beijing’s anxiety toward Taiwan’s democratization and its “demonstration effect” on the Hong Kong opposition. Beijing forestalled the opposition from claiming the right to self-determination. This is how Beijing has defined its so-called “core interest” in dealing with Hong Kong and Taiwan issues. Under such circumstances, many democrats had shied away from Taiwan’s democracy movement or independence advocates until the localist turn.

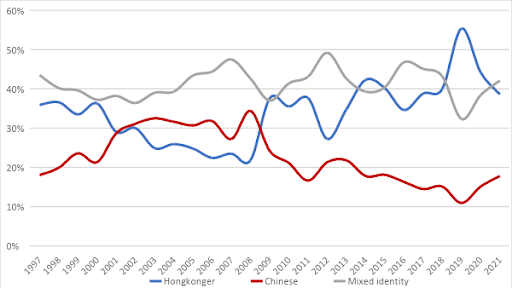

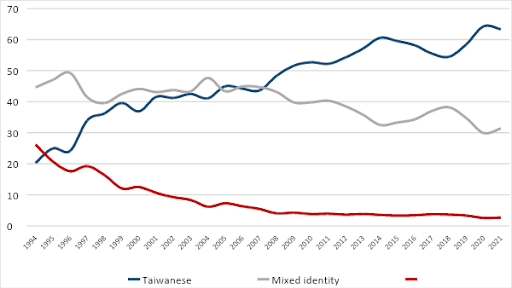

Beijing’s aggressive policies caused local groups advocating self-determination and a distinctive Hong Kong identity—as opposed to Chinese identity—to mushroom,10 and, although these rarely advocated independence, this Hong Kong identity surged (see Figure 1). A superficial resemblance to identity changes in Taiwan might have further aggravated a suspicious Beijing, but, viewed closely, the differences are obvious: Taiwan enjoys de facto sovereign status with a high degree of statehood, whereas Hong Kong is a special region that, in recent years, has come within the PRC’s ever-tighter grip.11 Taiwanese identity has overtaken a mixed Chinese-Taiwanese identity and become predominant from 2008, while Chinese identity has shrunk to an insignificant level for an extended period. Mixed identity remains substantial but is consistently smaller than Taiwanese identity by a wide margin (see Figure 2). By contrast, Hongkonger identity, despite overtaking Chinese identity in 2009, remains entangled with mixed identity, as was the trend in Taiwan during the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s. It has fluctuated abruptly, unlike the relatively steady growth of Taiwanese identity. The Anti-Extradition Movement mobilized a spike in Hongkonger identity in 2019,12 but Beijing’s harsh crackdown caused a sudden drop in the following two years. Yet the long-term growth trend in Hongkonger identity has undoubtedly worried Beijing, just as firmer Taiwanese identity has been linked with resistance to China’s unification offensive. Further breaking down ideas of identity in Hong Kong by age and focusing on youth (aged 18-29), the trend toward indigenization must have Beijing on tenterhooks: in 2011, 46.8% identified themselves as Hongkongers, 13.1% as Chinese, and 40.1% as mixed identity. By 2019, Hongkonger identity had jumped to 82.6%, Chinese identity had shrunk to just 1.9%, and mixed identity had declined to 15.5%.13 The sharp rise of Hongkonger identity in the younger generation completely changed the political landscape; localist activism had paved the way for Hong Kong-Taiwan civic movement connections.

Figure 1: Trend in Hong Kong’s Political Identity, 1997-2021. Sources: Compiled from Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute (PORI). The second half-year data for each year were adopted for analysis. Accessible here.

Figure 2: Trend in Taiwan’s Political Identity, 1994-2021. Sources: Election Study Center, National Chengchi University, accessible here.

The “China factor” proved counterproductive to Beijing by provoking lively exchanges between activists and intellectuals from both places:14 Taiwanese wanted to learn how to guard against China’s united front work, while Hongkongers wanted to tap into Taiwanese resistance to Kuomintang rule under martial law. In 2014, a Hong Kong University student journal, Undergrad, published a volume On the Hong Kong Nation, which included a chapter written by a Taiwanese scholar specializing in nationalism. The idea of a Hong Kong nation was more heuristic and imaginary than realistic at that stage, but with the then-Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying’s fierce criticism of China the following year, the book became an instant bestseller. The episode hinted at embryonic national sentiment among the younger generation and public distaste for Beijing’s mouthpieces, anticipating the larger protest cycle in the next stage.

In March 2014, students and social movement activists stormed Taiwan’s parliament (Legislative Yuan) to protest against the Services Trade Agreement signed by Taiwan’s ruling Kuomintang (KMT) government and China. The Agreement had lacked due process of parliamentary review and would further integrate Taiwan’s economy into Chinese markets, something which caused grave concern among many Taiwanese. Evoking unprecedentedly strong sentiment to defend Taiwan against Chinese domination, the young demonstrators occupied parliament for several weeks and succeeded in having the trade pact suspended. Hong Kong’s social media revealed powerful sympathy and support for this Sunflower Occupy Movement, and thousands of students and activists staged a rally to express solidarity with Taiwan. An opposition party leader who came to Taiwan to “boost the students’ morale” said that “[b]oth Taiwan and Hong Kong must face the problem of economic leaning-to-China,” and that she didn’t want to see “the Taiwan of tomorrow become the Hong Kong of now.”15

Later that year, Hong Kong’s Occupy Central Movement (calling for universal suffrage in choosing the Chief Executive) gradually gained momentum. On July 1, 2014, the anniversary of the handover, when pro-democracy forces staged a parade as in previous years, social movement groups from Taiwan joined the event for the first time.16 Public anger reached boiling point when Beijing officially repudiated universal suffrage at the end of August; a student hunger strike developed into the 79-day Umbrella Movement. As videos of police firing tear gas at peaceful protesters shocked the world, Taiwan activists organized a sit-in in front of Hong Kong’s representative office in Taipei. Petitions and meetings organized by Hong Kong students in Taiwan attracted student support across the Taiwan. Many Taiwanese advocates and scholars, meanwhile, went to Hong Kong’s protest sites. The Hong Kong government did not yield to the demands of the protestors; instead, it used a strategy of attrition to prevent the Occupy Central and Umbrella Movements from achieving the democracy that Hongkongers wanted,17 only to sow the seeds for popular uprisings and youth activism in the coming years, when young activists and professionals went on to organize many more civic groups and political parties.

Both Hong Kong and Taiwan have undergone political transformation in the face of Beijing’s ever-more aggressive policies. The 2012-2014 protest cycles in Taiwan and Hong Kong brought about the first round of cross-border civil society interplay, but with divergent outcomes. The Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong was eventually thwarted partly by line struggle (i.e., disputes caused by strategic and tactical disagreement among different protest groups), leadership competition, and a lack of solidarity. In contrast, Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement disrupted China’s cooperation with the KMT. Though with divergent movement outcomes, both campaigns opened up new spaces for youth politics in their respective domains.18

In Taiwan, in the wake of the Sunflower Movement, a new generation established political parties. At the same time, the ruling Democratic Progressive Party absorbed scores of activists into its party apparatus and the new government, defeating the KMT in the 2014 and 2016 elections, while the recently founded New Power Party took five seats in the 2016 parliamentary elections.

Inspired in part by the success of Taiwan’s youth politics, Hong Kong activists organized new parties (including the internationally renowned Demosistō) and devoted themselves to elections at different levels, achieving significant gains. The vibrant post-Umbrella youth politics breathed fresh air into a somewhat hackneyed opposition. Young localist and pro-self-determination candidates grabbed six of the 29 seats gained by the pan-democratic camp in the 2016 Legislative Council elections.

Lively exchanges between young activists on both sides also attracted unwanted attention: when Demosistō’s Joshua Wong and Nathan Law visited Taiwan in 2017, they were followed and threatened by pro-China groups (later found to have gangland connections) cultivated by Beijing over the years to counter the democracy movement and attack activists. This countermeasure, developed by the CCP, represents just one of the regime’s strategies of attrition.19

The Anti-Extradition Movement and Taiwan’s support

Since the start of partial direct elections to the LegCo in the 1990s, Hong Kong’s pan-democratic parties continued to win elections, but the biased rules of the game nevertheless allowed pro-establishment cliques to control the government (see Tables 1 and 2 for vote shares and seat distributions in LegCo elections). Pan-democrats have enjoyed an absolute majority in direct elections but have been unable to win a majority of seats under the rules in place. As for the special executives, Beijing has simply hand-picked them with perfunctory indirect elections. This explains quite why democrats pushed hard for direct elections while Beijing sternly opposed them.

Table 1: Vote Shares in Hong Kong’s Legislative Council Elections: 2004-2016

| Direct-vote districts | “Super District” (District Council functional constituency, direct vote) | |||

| Year | Pro-establishment candidates | Pan-democratic candidates | Pro-establishment candidates | Pan-democratic candidates |

| 2004 | 36.9% | 60.5% | N/A | N/A |

| 2008 | 39.8% | 59.5% | N/A | N/A |

| 2012 | 42.7% | 56.2% | 45.4% | 50.7% |

| 2016 | 40.2% | 55.0%* | 42.0% | 58.0% |

* Including pan-democrats in the conventional sense, and localist and pro-self-determination candidates.

Source: Compiled from Electoral Affairs Commission, The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Accessible here.

Table 2: Distribution of seats between pan-democratic and pro-establishment camps in Legislative Council elections: 2004-2016

| Year | Pro-establishment parties | Pan-democratic parties | |||||||

| Direct- vote

districts |

Functional constitu-encies | Total seats | Direct- vote

districts |

Functional constitu-encies | Total seats | ||||

| 2004 | 11 | 23 | 34 | (56.7%) | 19 | 7 | 26 | (43.3%) | |

| 2008* | 11 | 25 | 36 | (51.4%) | 19 | 4 | 23 | (32.9%) | |

| 2012 | 17 | 26 | 43 | (61.4%) | 21 | 6 | 27 | (38.6%) | |

| 2016* | 16 | 24 | 40 | (57.1%) | 22** | 7 | 29 | (41.4%) | |

* One independent was elected respectively for 2008 and 2016. ** Including pan-democrats in the narrow sense, and localist and self-determination candidates.

Source: Compiled from Electoral Affairs Commission, The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Accessible here.

Since the Umbrella Movement, increasing distrust of the Chinese government and erosion of “One Country, Two Systems” has spawned enormous social discontent. In spring 2019, an Extradition Law Amendment Bill triggered fears of Hong Kong residents being extradited to China and ignited a new protest cycle, leading to an unprecedented scale of mobilization that summer, with rallies of over one million people filling the streets. Global news media reported police brutality disproportionate to the protesters’ vandalism and occasionally violent behavior: in less than a year, the police fired 16,138 tear gas canisters, 10,076 rubber bullets, 2,026 bean bag rounds, 1,873 sponge grenades, and 19 live bullets.20 The police reported 600 injuries, but many more civilian injuries can only be estimated (many protesters refused medical treatment for fear of being reported), while there were also numerous reports of police torture and abuse. Photos of pole-wielding gangsters attacking empty-handed protesters and subway passengers spread worldwide. Public demands for an independent committee to investigate the “merging of police and gangsters” went unanswered, spurring even larger demonstrations.

The movement was dubbed the “Water Revolution” for its fluidity, spontaneity, and decentralized leadership. Despite its lack of conventional vertical coordination, it demonstrated the historic cooperation and solidarity of Hong Kong citizens, which prevailed over the line struggle and distrust that had derailed the leadership of previous mass rallies, especially the Umbrella Movement.21 Creative coordination channels, primarily through social media, also played a crucial role in the face of successive police crackdowns and arrests. When the protesters met with the regime’s unresponsiveness and police brutality, many expressed their determination to escalate the conflict by an uncoordinated strategy of laamchau or “burning together”—perishing along with their enemies.22

A survey of Umbrella protest sites from June to December 2019 indicates that “young people were a major force.” Analyzing the results of 26 on-site surveys, “the percentage of respondents below age 35 ranged from 41.6% to a staggering 93.8% (over 60% in most of the surveys) … A further age breakdown of the young protesters illustrates that the 20-24 and 25-29 age groups were the most active. The proportions of the former group ranged from 9.4% to 54.2%, but most were roughly 20% to 30%, whereas the latter group’s proportions ranged from 11.6% to 34.2%, with most roughly 10% to 20%. Participation by respondents under age 20 also was notable, accounting for a few percent to over one-fifth (22.5%) of the protester population throughout the Movement.”23 Aggregating the data of 26 surveys, a holistic picture emerges: among the total 17,233 respondents, 1,875 (or 15.6%) were under 20; 4,319 (36.0%) were aged between 20 and 24; 3,654 (30.5%) were between 25 and 29.24

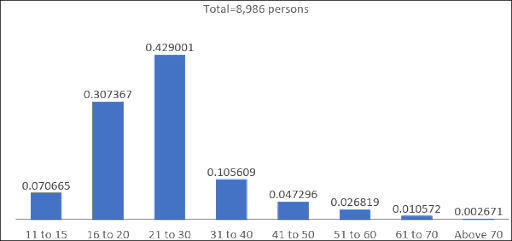

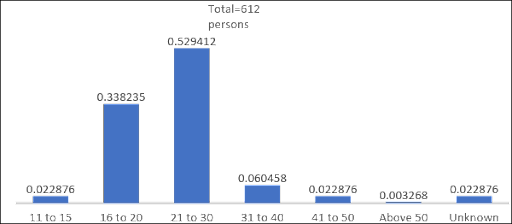

During the Movement, the police arrested 8,986 persons in 2019, including 2,899 in November alone. Among the arrestees, 42.9% were between age 21 and 30, 30.7% between 16 and 20, and 7.1% between 11 and 15 (see Figure 3). Among the 612 persons charged with riot as of May 2020, 89.1% were under 30 years of age, including 14 adolescents under 15 (Figure 4). The numbers support the image of a youth (or even adolescent) street movement. At the same time, numerous older citizens and veteran democracy advocates actively provided coordination, logistics, public discourse, and various other kinds of assistance.

Figure 3: Arrests by age during the Anti-Extradition Movement, June 2019-May 2020. Sources: HK 01, June 8, 2020, accessible here.

Figure 4: Persons charged with riot by age during the Anti-Extradition Movement, June 2019-May, 2020. Sources: Stand News, June 12, 2020, accessible here.

Under the crackdown, Hongkonger identity soared to 55.4% in 2019, a 10% leap from the previous year, while Chinese identity and mixed identity reached their nadirs at 10.9% and 32.3% respectively (see Figure 1).

Undeterred by police brutality, many young oppositionists participated in the district council elections in November 2019, which attracted a turnout of 71%, compared to just 47% in 2015. The democrats won 388 seats (57% of votes), while the establishment parties gained just 58 seats (41% of votes). The election was seen as a referendum on the legitimacy of Beijing and the Hong Kong authorities. It once again sent a clear message that if universal suffrage were applied to higher-level elections, the pan-democrats would easily win power. The Anti-Extradition Movement and district council elections catalyzed Beijing’s further fierce repression.

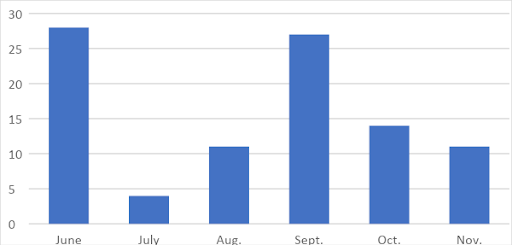

When news of the Anti-Extradition protests reached Taiwan, Taiwanese youth and NGO activists rushed to mobilize rallies, sit-ins, and petitions, and set up Lennon Walls on campuses around the country to support Hong Kong. Organizers collected donations to purchase anti-tear gas kits and shipped them to Hong Kong while urging the government to aid young protesters seeking refuge in Taiwan. The author’s research team documented nearly one hundred episodes of protest in support of Hong Kong’s resistance movement from June-November 2019, indicating the intensity of mobilization. See Figure 5.

Figure 5: Number of Hong Kong-related protest events in Taiwan, June-November 2019. Sources: Coded and compiled from Liberty Times (Ziyou Shibao, Taipei) news archive.

“Standing with Hong Kong” became not merely a street slogan but a popular mandate in Taiwan. Public opinion urged Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen to provide asylum for young protesters who faced persecution and escaped to Taiwan. According to a May 2020 survey by Academia Sinica, 67% of Taiwanese supported Hongkongers’ resistance, while among those aged 18 to 34 the figure reached 85%.25 Global media widely reported Taiwanese support for Hong Kong’s civil resistance, but some criticized the government’s lukewarm or limited support.26 Treading a fine line between defending a besieged Hong Kong and avoiding an overreaction from Beijing, the government opted for collaboration with Taiwanese civic groups, but in a more low-profile manner. In July 2020, the government set up an office to take charge of relief work. Between 2019 and 2021, some 100 young Hongkongers who had participated in the Anti-Extradition Law protest found sanctuary in Taiwan, receiving education, employment, and financial aid.

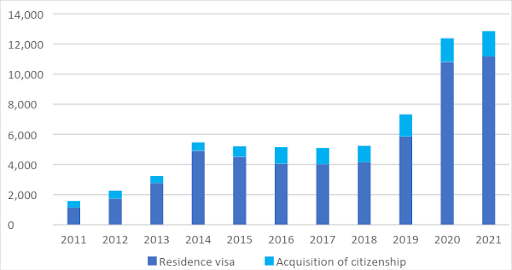

Meanwhile, an influx of Hong Kong migrants has been evident. Applicants for Taiwanese residence visas and citizenship have increased substantially in recent years. While the Umbrella Movement in 2014 led to a mini peak, the Anti-Extradition movement and the implementation of the National Security Law brought about a massive exodus. Many emigrants saw Taiwan as a new home, insurance for an alternative domicile, or a transit point to other Western democracies. In 2019, nearly six thousand acquired residence visas, a 41% increase from the previous year, and more than one thousand acquired citizenship, a 35% increase. Subsequently, the influx became even more remarkable, with over ten thousand obtaining residence visas for two consecutive years. During the same period, 3,261 persons obtained citizenship (see Figure 6). To sum up, Taiwan accommodated over thirty thousand Hong Kong immigrants in the period 2019-2021, an impressive record compared to other, larger, democratic countries. For comparison, the UK government offered 47,924 entry visas to Hongkongers via the British National Overseas (BNO) route in 2021, accounting for 81.2% of the total entries from Hong Kong;27 the US government issued 2,416 migrant visas to Hongkongers during 2020-21 fiscal year.28

In 2022, a public debate erupted in Taiwan over the Hong Kong immigrant issue. Many people, including some ruling party legislators, were concerned about national security implications if the PRC were to infiltrate spies into Taiwan, taking advantage of its lenient Hong Kong policies. This debate has affected the sentiments of those protesters seeking refuge in Taiwan, who fear persecution if forced to return to Hong Kong when their temporary residence visas expire. To mitigate the anxieties of the public and the protesters simultaneously, the government resorted to a roundabout way of providing asylum: in July 2022, it quietly passed confidential special measures for long-term residence and prospective citizenship applications for asylum seekers.29

Figure 6: Trend in Taiwan government granting residence visas and citizenship to Hong Kong people, 2011-2021. Source: The Mainland Affairs Council, Taiwan.

The Anti-Extradition Movement coincided with Taiwan’s presidential election of January 11, 2020, following the ruling DPP’s defeat by the KMT in local elections the previous year. In a major speech to “Taiwanese compatriots” in early 2019, China’s leader Xi Jinping called for unification under the “One Country, Two Systems” formula, adding that “we do not promise to renounce the use of force.”30 Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen immediately rebuffed Xi’s speech. The common perception is that Xi was taking advantage of the KMT’s victory to promote unification or create space for Beijing’s local collaborators to attack “Taiwan independence forces,” but this proved counterproductive.

That year, on top of the Hong Kong crackdown, Taiwan’s younger generations began to feel deep angst at the danger of losing their country (wang guo gan), as a result of China’s information warfare and threat of “forceful unification”. The Legislative Yuan’s passage of Asia’s first same-sex marriage bill in May created a more vital cause for younger progressives to rally behind Tsai, and they helped her win a second term. Their wang guo gan translated into a momentum for collective action on behalf of Hong Kong, as it also meant fighting for Taiwan’s freedom. Chants of “Today Hong Kong, Tomorrow Taiwan” filled the air.

The harshness of China’s policies toward Hong Kong have stirred robust support for Taiwan’s independence, especially among those 20-35 years of age: support for independence among youth grew from 45.2% in 2011 to 60.7% in 2019.31 It’s no exaggeration to say that China’s impact has rejuvenated the independence movement in Taiwan, with Hong Kong’s sacrifice serving as an alarm bell.

Beijing has Built a “Berlin Wall” Separating Hong Kong from the World

On June 30, 2020, China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) passed a National Security Law (NSL) specific to Hong Kong, effective immediately. On the same day, the US government revoked part of Hong Kong’s special trade status; the youth party Demosistō was forced to declare itself disbanded. On July 1, the Taiwanese government opened a “Taiwan-Hong Kong Exchange Office” for humanitarian relief, as mentioned above. On July 2, Hong Kong police arrested 370 people, including ten suspected of violating the NSL; Nathan Law, a legislator and founding member of Demosistō, fled Hong Kong; US Congress passed the Hong Kong Autonomy Act. On July 3, the Chinese government announced appointments to critical posts in Hong Kong, authorized by the NSL. By July 6, the rules for implementing the NSL were already in place, with some thought even given to targeting Taiwan: Article 43 of the NSL’s implementation rules, for instance, stipulates that the Hong Kong Police can request information from foreign and Taiwanese political organizations and their agents on activities involving Hong Kong, something which poses a direct threat to Taiwanese personnel in Hong Kong. The result has been to force Taiwan to compromise or withdraw its office from Hong Kong, with Taiwanese personnel otherwise facing the risk of imprisonment. The Mainland Affairs Council was forced to withdraw its officials in Hong Kong within a short period (see below).

The NSL set out a wide range of vaguely defined offences and unimaginably broad punishments. This legal blitzkrieg took the world by surprise.32 In retrospect, however, Beijing had been preparing for it for months, if not years, in advance, given the speedy legislation and deployment of personnel and resources. Its primary goals were to punish those who commit “subversion of state power” or “incitement to subvert the state” and to prevent “foreign forces interfering with Hong Kong affairs.” Beijing would move to disrupt the flow of foreign funds and aid to Hong Kong NGOs and civic groups.

Beijing’s determination to block the opposition from winning the LegCo election scheduled for September 2020 was reflected in police harassment of primaries organized by the pan-democrats in July and the investigation of a private polling institute. The primaries nevertheless attracted more than 600,000 voters, and many young advocates were nominated. The Central Liaison Office (Hong Kong’s second government) condemned the democrats for violating the NSL by “performing a Hong Kong version of the color revolution,” referring to the movements in the former Soviet Union and elsewhere. The Hong Kong government disqualified twelve pan-democratic candidates and then announced the postponement of the LegCo election for one year on account of the coronavirus pandemic. Chief Executive Carrie Lam explained, “This is a difficult decision. We had the Center’s support. There’s no political consideration.”33

Moreover, in a clear case of Beijing’s direct intervention in Hong Kong affairs, the Standing Committee of the NPC in November 2020 disqualified four LegCo members on the grounds of “support of ‘Hong Kong independence,’ refusal to recognize the [Chinese] state’s right to exert sovereignty on Hong Kong, seeking foreign or offshore forces to interfere with Hong Kong’s internal affairs.”34 Months later, the NPC passed the “Decision on Improving Hong Kong’s Electoral System,” a game-changer assuring the Center’s complete control over Hong Kong’s elections. The new rules stipulate that candidates for both Chief Executive and legislators must pass a vetting and nomination process; the National Security Division of the Hong Kong Police Force first vets the eligibility of candidates, which is then forwarded to the National Security Council and then to the Candidate Qualifications Committee. In addition, the LegCo was expanded from 70 seats to 90 seats, with 40 seats decided by the Election Committee and 30 seats by functional constituencies; seats filled by direct election have been reduced to 20, compared to the prior system of 40 seats by direct election out of a total 70. In December 2021, the LegCo elections produced 89 pro-establishment seats and one non-establishment token seat. The turnout was a low 30% for the direct election constituencies, in contrast to the range of 44%-58% in previous elections over the last two decades. Such lukewarm participation shows society’s passive resistance to the post-NSL regime. Beijing now controls Hong Kong’s political society in a most watertight way, although civil society still has the breathing space of “infrapolitical resistance.”35

On January 6, 2021, the police arrested 55 participants in the pro-democracy primaries. Forty-seven were charged with “subversion of state power” under the NSL, virtually wiping out the opposition. Since the implementation of the NSL, 154 people have been arrested, mostly on charges of “subversion,” “collusion with foreign forces,” “secession from the state,” and “terrorism.” Among them, 26 were arrested merely for speech-related acts such as shouting or displaying slogans; the first person sentenced under the NSL was indicted for carrying a banner with the Water Revolution slogan, “Liberate Hong Kong, the revolution of our times!”36

Beijing’s persecution of Hong Kong democrats did not stop at LegCo but was extended to the district councils. In 2021, in an episode that showed how fragile Hong Kong’s electoral system has become under the NSL, more than 200 pan-democratic district councilors resigned after media reports that the government might disqualify up to 230 members for failing to meet oath requirements and that it might even recover salaries and allowances.

Many activists have been forced into exile and put on wanted lists. Scholars and activists accused by the pro-China media, or facing arrest, have chosen to leave Hong Kong, while others have decided to stay in Taiwan. At least nine scholars have been falsely accused or unfairly treated since September 2021. Long-established civic organizations such as the Professional Teachers’ Union, the Civil Human Rights Front and the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU, representing more than 93 affiliated labor organizations) have been forced to disband. The HKCTU is one of just a few civil society organizations that closely interacted with Taiwan’s trade unions before 2012. In September, the National Security Department claimed that the Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, renowned for organizing the annual candlelit vigil in Victoria Park commemorating the Tiananmen protests and massacre, was a “foreign agent.” When staff refused to hand over documents, they were arrested. The alliance’s vice chair Chow Hang-tung said, “We won’t help you spread fear.”37 Wall-fare, a support group for prisoners’ rights founded after the Anti-Extradition Movement, was also forced to close.

Previously, the police had raided the offices of the Apple Daily (a major media arm of Next Digital Limited), the popular opposition paper in Hong Kong, and arrested five senior staff on charges of collusion with foreign or extraterritorial forces and endangering national security.38 If convicted, the defendants will receive heavy sentences. The publication was forced to shut down within a week. Next Digital’s owner, Jimmy Lai, was already in custody under previous criminal charges. As a result, many independent online news channels began self-censoring or scrubbing “sensitive” reports and op-eds from their websites.

The Next Digital persecution not only terminated the most critical pro-democracy media in Hong Kong but also saw their assets frozen, including those overseas. With the charge of collusion with foreign forces, the case was also linked to the “Li Yu-hin case” and the “12 Hongkongers fleeing case,” the former involving alleged “transnational money laundering” and the suspected role of related persons in the US; the latter involving 12 young people intending to smuggle themselves into Taiwan by boat. The prosecutor alleged that Jimmy Lai was behind the conspiracy.39

The prosecutions of Jimmy Lai and Next Digital were soon linked to Taiwan. The Taiwan-based Apple Daily was declared bankrupt at the end of 2021. A Hong Kong court-appointed liquidator sought permission to order the newspaper and Next Magazine to turn over all their assets. (Jimmy Lai was an investor in both news outlets, but they were not subsidiaries of the Hong Kong-based Next Digital.) Those assets included their news archives and data on employees, op-ed contributors, and subscribers, involving personal information that could be used by the Hong Kong and Chinese authorities for political purposes. Civic groups in Taiwan urged the government to take action to protect the assets from being used for infringing privacy and harming press freedom.40

The NSL putsch caused a deterioration in Hong Kong’s political relations with Taiwan. In May 2021, the Hong Kong government abruptly closed its office in Taipei. Macao followed suit the next month. In June, Taiwan’s Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) announced it had withdrawn its officials from Hong Kong after their visas expired: the Hong Kong government had made signing a “One China Pledge” a condition for visa renewals. Given the unlikelihood that Taiwan’s representatives would sign a document that implicitly recognized the PRC’s sovereignty claims over Taiwan, this requirement was a pretext for severing Taiwan’s ties with Hong Kong.

So far, Beijing has achieved almost everything it wanted: stifling Hong Kong’s civil resistance, cutting off civil society’s connections with foreign countries, arresting most dissident leaders, suppressing freedom of expression, and making a travesty of elections to eradicate Hong Kong’s “deep state” and complete the so-called “second handover.”41 Within eighteen months, between June 2020 and November 2021, sixty civil and political groups were forced to disband, including political groups and parties, trade unions, protest organizations, protester support groups, church organizations, media, and others. The dismantling of the most vibrant civil society sector led to the silencing of the resistance movement. Figure 7 illustrates the two waves of dissolution of civic organizations. The first wave occurred when the NSL was enacted and implemented on June 30, 2020. All the disbanded groups were dangerous political and protest organizations in the eyes of Beijing. The second wave was concentrated in mid-2021, especially between July and September, and focused on trade unions and various civic organizations. It was at this time that the arrests of the Next Digital editors and other political cases sent a chill through Hong Kong.

Figure 7: The dismantling of social and political groups, June 2020-November 2021. Source: Compiled from a special report by Stand News (disbanded in December 2021) and the author’s research team.

So, the NSL has legalized a police state and installed a quasi-martial law regime. It has amounted to building a “Berlin Wall” separating Hong Kong from the Western democracies. But the crackdown on the Anti-Extradition movement has antagonized the Hong Kong people, and the NSL has created a long-term governance problem. Moreover, the NSL’s apparatus has torn up the promise of One Country, Two Systems, deepening the image of a PRC diffusing autocracy and further alienating Taiwan. The West could not stop Beijing from building the wall, but it did require Beijing to pay a considerable price. Western countries began to impose sanctions on Hong Kong and Chinese officials. In August 2020, the US government put six top Hong Kong officials and five Chinese officials in charge of Hong Kong affairs on a list of “Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons,” including Carrie Lam, the Chief Executive of Hong Kong, and Xia Bao-long, the director of the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macao Office. The US government also suspended Hong Kong’s special status. It doubled down on its sanctions list by adding fourteen vice-chairpersons of the National People’s Congress in December 2020 and six Hong Kong and Chinese officials in charge of Hong Kong affairs in January 2021. The UK government opened a new visa route for Hong Kong people with British National Overseas (BNO) status. The Canadian government offered new pathways to permanent residence to facilitate the immigration of Hong Kong residents.

An Uneasy Beginning of Decolonization

The current Hong Kong situation is the product of a long-term accumulation of crises and the consequences of the broader interplay among nations. China has long suspected a Western conspiracy. Soon after the signing of the Sino-British Agreement in 1984, China became profoundly uneasy when the British Hong Kong government issued a white paper intended to gradually expand the number of directly elected seats in the run-up to 1997. According to Christine Loh, who was close to the pro-Beijing establishment:

They (Beijing) concluded that Britain wanted to establish a representative government as a sign of returning power to the people, not to China, and to hand over the decision-making power of the Executive Council to the Legislative Council, a fundamental change to the colonial government structure and a departure from Deng Xiaoping’s guiding principles in drafting the Basic Law. In other words, Britain is attempting to implement many changes in the next thirteen years of British rule, creating many problems for the future government of the Hong Kong SAR. In the eyes of Chinese officials, the cunning British are playing the “democracy card” to disrupt China’s plans. It would divide Hong Kong society and foster pro-British forces to act as British proxies and continue to govern Hong Kong after 1997 as if Britain continued to exist.42

Such a description of the CCP’s perception was a succinct premonition of the “deep state” accusations of later years. Hong Kong’s people lost confidence in Beijing after the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown. The British government indicated that it would speed up the process of direct elections in Hong Kong, but the CCP disagreed. Beijing even believed that, during the Tiananmen Movement, “certain people from Hong Kong and Macau went to the Mainland and played a role in the turmoil there.” The CCP presumed that “Britain has changed its policy toward China regarding Hong Kong and is prepared to use Hong Kong to destabilize the Chinese Communist regime. … Hong Kong is no longer a Sino-British issue; it has become part of a Western anti-Chinese conspiracy.”43

Evidently, as early as 1989, Hong Kong was suspected of colluding with foreign powers in a conspiracy of subversion against China. This view has been an undercurrent in China’s policy toward Hong Kong for decades. In 2003 the Hong Kong government tried to legislate Article 23 of the Basic Law: “Prohibiting foreign political organizations or bodies from carrying out political activities in the Hong Kong SAR, and prohibiting political organizations or bodies in the Hong Kong SAR from establishing ties with foreign political organizations or bodies.” The legislation was halted due to an unprecedented rally in opposition, but the CCP never relinquished it.

The Basic Law reserved several means for the PRC’s central government to directly control Hong Kong. Article 23 is one among them, and the abortive legislation sowed a seed that would remain a flashpoint. Moreover, the Center reneged several times on the universal suffrage promised in the Basic Law. In 2014, the Umbrella protests reacted to the Center’s white paper renouncing the direct election of the Chief Executive. The “Fishball Revolution”—civil unrest in Mong Kok during the 2016 Chinese New Year holidays—proved how inflammable Hong Kong politics had become.

Hong Kong had long enjoyed a degree of freedom under British colonial rule and developed a vibrant civil society. It was natural for there to have been cross-border flows of ideas and protest repertoires. Affinity between Taiwan and Hong Kong was evident for geopolitical proximity, linguistic affinity, and, above all, the Chinese government’s framing of Hong Kong and Taiwan in a coherent action plan, with its One Country, Two Systems experiment applying also to Taiwan. Beijing created trouble for itself. It was the China factor that made both civil societies intimate allies.

In retrospect, the permanent crisis in Hong Kong originated from a clash of two political visions: the CCP’s authoritarian control and the people’s will to pursue democracy (falsely attributed to a mere conspiracy of the West). The Extradition Law Amendment Bill led to Hong Kong citizens staging immediate protests, which in turn substantiated Beijing’s fear of democratization. Beijing’s fierce crackdown forced the West to adopt sanctions on China and provide relief to political refugees. Above all, it would be a moral crisis if Taiwan and the Western democracies simply sat back and watched demonstrators being cruelly beaten. Beijing vowed to retaliate against the involvement of Western governments. Yet, a fear of destabilizing Hong Kong’s financial sector and capital flight may have led Beijing to exercise a certain degree of restraint since the passing of the NSL. In June 2021, reports spread that Beijing was considering applying the Anti-foreign Sanctions Law in Hong Kong. The law states that no organization or individual may enforce or assist foreign countries in enforcing discriminatory restrictive measures against Chinese citizens and organizations, and that failure to enforce or cooperate with Chinese countermeasures may result in legal liability. In the end, Beijing decided not to extend that law to Hong Kong.44

Conclusion: Creation of a Long-distance Resistance Movement

Hong Kong’s resistance and repression have their rhythm. The predicament of the democracy movement can be traced back to its duel with Beijing during the Occupy Central Movement and the Umbrella uprising. Over the last three years, the deterioration of the situation has been partly shaped by the global geopolitical environment, with growing Sino-American tensions that some have called the “New Cold War” playing a critical part in Beijing’s decisions on Hong Kong. But Beijing’s perception of the situation has played a significant part. Judging from Chinese leaders’ speeches, strategists’ writings, and the content of the NSL, Beijing is suspicious of Hong Kong’s connections with foreign forces—Western democracies and global civil society—and the possibility of a “color revolution” or peaceful evolution. The US understands those Chinese perceptions well, and the secretary of state has tried to persuade Beijing that regime change is not on the agenda: “Now, Beijing believes that its model is the better one; that a party-led centralized system is more efficient, less messy, ultimately superior to democracy. We do not seek to transform China’s political system.”45 Given that the Xi regime is the ultimate authority over Hong Kong, the situation is unlikely to change unless Beijing loosens its grip in the future.

Yet, concomitant to Hong Kong’s fall, Beijing’s aggressive influence operations around the globe have stirred up numerous instances of pushback.46 The model of the Hong Kong-Taiwan civil society nexus against the “China factor” has expanded geographically. China has, for example, invested heavily in Thailand and enjoyed massive influence there. As elsewhere, Chinese nationalist netizens have censored Thailand’s civil society activism that has supported Hong Kong and Taiwan. The PRC’s “wolf warrior diplomacy” has encouraged such netizen behavior. The cross-border witch hunts for evidence of “Hong Kong independence” and “Taiwan independence” have caused a moment of solidarity against China.47 An online “Milk Tea Alliance” movement, mobilizing social media activists from Taiwan, Hong Kong, Thailand, and Myanmar, has emerged.48

The center of resistance has shifted with the deteriorating situation in Hong Kong. Overseas movements have flourished in the past few years, as opposition elites have fled and established various organizations in the West, particularly in the US, UK, and Canada. The author’s research team has documented forty-three such organizations established between 2019 and 2021. Likewise, Taiwan has become a new hub of activism, although it is highly constrained under continuous pressure from China. Taiwan’s decade-long civil society engagement with Hong Kong has been transformed, with new networks and spatial arrangements. People have acted in more careful and low-profile ways to protect those involved and to help preserve the embers of democracy in Hong Kong. More significantly, Taiwan-based Hongkonger organizations have mushroomed. We have collected a list of twenty new Hongkonger organizations, in four types:

- Three groups offering refuge and assistance to protesters in Taiwan.

- Six units for rights advocacy and services for Hong Kong fellow people.

- Three for academic and cultural exchanges.

- Eight “yellow-economy” restaurants and corporations.49

These groups have been in intense communication with civil society in Taiwan. By way of illustration, the Economic Democracy Union, a prominent Taiwanese civic organization well known for its fight against Chinese influence operations, co-publishes the magazine Flow HK with overseas Hong Kong activists.

Hong Kong’s current opposition to authoritarianism is akin to Taiwan’s under martial law (1949-1987). During that period, overseas Taiwanese organizations informed the world of KMT repression. They lobbied Western governments, trained activists and organizers, published banned books, connected with dissidents in their homeland, and helped them flee. These overseas activities proved vital for the continuation of resistance during authoritarian rule.

Today, the national security apparatus in Hong Kong has been creating not only the first generation of political prisoners but also a long-distance resistance movement. Hongkongers are keen to learn about Taiwan’s past experiences: how to wage a “war of position” after exhausting confrontations; how to resist brainwashing in schools and media and preserve historical memory; how to play with an “émigré regime” that needs legitimacy; and how to nurture offshore civil society and connect it with domestic fighters. For the foreseeable future, Hong Kong will continue to exist in the thrall of the NSL regime. But when the day of liberalization comes, an ongoing and transformed Hong Kong-Taiwan nexus will have contributed to that process.

The author thanks Lin Cheng-yu and Chiang Min-yen for research assistance; and Mark Selden and an anonymous reviewer for valuable comments and suggestions.

Notes

Wu Jieh-min, 2014, “The Civil Resistance Movements in Taiwan and Hong Kong under the ‘China Factor’” (Chinese), pp. 130-144 in Hsieh Cheng-yu, Nobuo Takahashi, and Huang Ying-che eds., Cooperation and Peace in East Asia (Taipei: Avant-Garde). See also Malte Kaeding, 2015, “Resisting Chinese Influence: Social Movements in Hong Kong and Taiwan,” Current History, Vol. 114, No. 773. pp. 210-216.

“’Occupy Central’ colluding with ‘Taiwan independence’ and ‘the merging of the two independence movements to ruin Hong Kong” (Chinese), Wenweipo, 24 October 2013.

“Analysis: Interaction of Opposition Forces in Taiwan and Hong Kong Causes Beijing to Be Wary” (Chinese), BBC News, 21 October 2013.

“Hong Kong pan-democrats are warned for contacting Taiwan’s green camp” (Chinese), Central News Agency (CNA), 22 October 2013.

“There is no way out for the merging of Hong Kong independence and Taiwan independence” (Chinese), Ta Kung Pao, 31 October 2013.

For different types of localism during its embryonic stage, see Sebastian Veg, 2017, “The Rise of ‘Localism‘ and Civic Identity in Post-handover Hong Kong: Questioning the Chinese Nation-state,” The China Quarterly, Vol. 230, pp. 323-47; Malte Kaeding, “The rise of ‘Localism’ in Hong Kong,” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 28, No.1. pp. 157-171; Samson Yuen and Sanho Chung, 2018, “Explaining Localism in Post-handover Hong Kong: An Eventful Approach,” China Perspectives, 2018/3, pp. 19-29.

One may wonder whether the territory still enjoys a certain degree of autonomy in the economic and financial sphere even under the National Security Law. Yet, Chinese state capital has become a significant player in Hong Kong, which endured a process of mainlandization of business circles. See Ho-fung Hung, City on the Edge.

The movement was a reaction to a proposed bill revising the Extradition Law that would have allowed extradition of criminal suspects to mainland China, which caused huge fear in Hong Kong, including among the Chinese citizens living there.

Calculated from the survey data provided by PORI. The second half-year data for each year were adopted for analysis.

There used to be frequent academic and civil society exchanges between Taiwan and China before the Xi regime consolidated its position. But the CCP’s tightening control of civil society and intensified cross-strait tensions have made exchanges difficult.

“2.3 thousand people brave cold wind, prefer to catch a cold rather than take the trade agreement,” United Evening News, 21 March 2014.

“Taiwan NGOs will not be absent, going to Hong Kong to show support,” Liberty Times, 1 July 2014.

Attrition is defined as “a mode of regime response that only tolerates protests ostensibly but uses a proactive tactical repertoire to discredit, wear out, and increase the cost of protests” by Samson Yuen and Edmund W Cheng, 2017, “Neither Repression Nor Concession? A Regime’s Attrition against Mass Protests,” Political Studies, Vol 65, Issue 3.

See Ming-sho Ho, 2019, Challenging Beijing’s Mandate of Heaven: Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement and Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; Wu Jieh-min, 2019, “Taiwan’s Sunflower Occupy Movement as a Transformative Resistance to the ‘China Factor’”, pp. 215-40 in Ching Kwan Lee and Ming Sing eds., Take Back Our Future: An Eventful Political Sociology of Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

For more on CCP and Hong Kong ruling elite countermobilization, see Samson Yuen (2021), “The Institutional Foundation of Countermobilization: Elites and Pro-Regime Grassroots Organizations in Post-Handover Hong Kong”. Government and Opposition, 1-22.

For different lines in the Umbrella Movement, see Samson Yuan, 2019, “Transgressive politics in Occupy Mongkok,” pp. 52-75 in Ching Kwan Lee and Ming Sing, eds., Take Back our Future: An Eventful Sociology of the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

See Ngok Ma, 2020, A Community of Resistance: Hong Kong’s Anti-Extradition Movement in 2019 (in Chinese), Taipei: Rive Gauche; Sebastian Veg, “Hong Kong Through Water and Fire: From the Mass Protests of 2019 to the National Security Law of 2020,” Diplomat, 1 July 2020.

Centre for Communication and Public Opinion Survey, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2020, “Research Report on Public Opinion during the Anti-Extradition Bill (Fugitive Offenders Bill) Movement in Hong Kong,” pp. 31-2, 20 May.

Recompiled from p. 32, Table 5, Research Report on Public Opinion during the Anti-Extradition Bill (Fugitive Offenders Bill) Movement in Hong Kong.

Survey by China Impact Studies (CIS), Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. Accessible here.

Compiled from “Entry clearance visa applications and outcomes,” Managed migration datasets, Home Office, UK.

Compiled from “Table XIV: Immigrant Visas Issued by Issuing Office (All Categories, Including Replaced Visas*)” Bureau of Consular Affairs, Department of State.

Hung-chin Chen and Chen-hao Lee, “The unspeakable special measures for Hong Kong people to apply for work permits in as shortly as five years to get an identity card,” 30 July 2022.

“Xi Jinping: Speech at the 40th Anniversary of the Release of the “Letter to Taiwan Compatriots,” 2 January 2019.

“Carrie Lam: Hong Kong Legislative Council election postponed a year because of the seriousness of the epidemic” (Chinese), CNA, 31 July 2020.

“Hong Kong Legislative Council: the Chinese People’s Congress Standing Committee resolution against the pro-democracy camp” (Chinese), BBC, 11 November 2020.

See Lake Lui, “National Security Education and the Infrapolitical Resistance of Parent-Stayers in Hong Kong,” forthcoming in Journal of Asian and African Studies.

Kelly Ho, “Activist Tong Ying-kit jailed for 9 years in Hong Kong’s first national security case,” Hong Kong Free Press, 30 July 2021.

Candice Chau, “Organisers of Hong Kong’s Tiananmen Massacre vigil refuse to comply with national security police data request,” Hong Kong Free Press, 6 September 2021.

“The case involving Jimmy Lai and Li Yu-hin: Chan Tsz-wah suddenly changed his appointment to a DAB lawyer” (Chinese), RFA, 14 April 2021.

Hsieh Chun-lin and Jake Chung, “HK liquidator must be kept from Taiwan’s media: group,” Taipei Times, 26 November 2021.

Tien Fei-long, “Why does Leung Chun-ying keep his eyes on HSBC?” (Chinese), Ifeng.com, 5 June 2020; Cheng Yong-nian, “Why do we need a second ‘handover’ for Hong Kong?” (Chinese), Orange News, 20 August 2019.

Christine Loh, 2011, The Underground Front: A History of the Chinese Communist Party in Hong Kong (Dixia Zhenxian: Zhonggong zai Xianggang de lishi) (Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press), p. 184.

Iain Marlow, “China to Shelve Anti-Sanctions Law in Hong Kong, HK01 Says,” Bloomberg, 5 October 2010.

Antony J. Blinken, “The Administration’s Approach to the People’s Republic of China,” US Department of State Press Release, 26 May 2022.

Fong, Brian, Wu Jieh-min, and Andrew Nathan, 2021, China’s Influence and the Center-periphery Tug of War in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Indo-Pacific (New York: Routledge).

For a case study of a witch hunt for “Taiwan independence,” see Liao Mei, 2021, “China’s influence on Taiwan’s entertainment industry: The Chinese state, entertainment capital, and netizens in the witch-hunt for ‘Taiwan independence suspects,’” Fong, Wu, and Nathan, China’s Influence and the Center-periphery Tug of War in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Indo-Pacific pp. 224-40.

Nicola Smith, “#MilkTeaAlliance: New Asian youth movement battles Chinese trolls,” The Telegraph, 3 May 2020; Jasmine Chia and Scott Singer, “How the Milk Tea Alliance Is Remaking Myanmar,” The Diplomat, 23 July 2021.

The “yellow economy,” a practice of mutual help and reciprocity growing out of the civic movement in Hong Kong, was composed of small businesses “with pro-democracy posters [to] attract supporters who want to continue the movement.” It was later introduced into Taiwan by Hongkongers. For the idea of the yellow economy, see Simon Shen, “How the Yellow Economic Circle Can Revolutionize Hong Kong,” The Diplomat, 19 May 2020.