Abstract: In 2016 and 2017, members of Ontario Provincial Parliament and the Parliament of Canada submitted bills to declare commemorative days for the Nanjing Massacre. In response, the National Association of Japanese Canadians mounted a campaign against the commemorative days, arguing that memorialization of the Nanjing Massacre would make Japanese Canadians vulnerable to racial persecution akin to the animus that led to mass incarceration during the Second World War. This paper investigates the transnational political forces that have shaped the controversy around the commemorative days, illuminating the conflicted racial, ethnic, and national affiliations that structure Japanese Canadian community, and Canadian politics more broadly.

Keywords: Japanese Canadians; Nanjing Massacre; “History Wars”; National Association of Japanese Canadians

Canadian and Japanese: The National Association of Japanese Canadians’ Opposition to the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day

On December 5, 2016, Member of Ontario Provincial Parliament Soo Wong read Private Members Bill 79 to proclaim a provincial commemorative day for the Nanjing Massacre. Wong’s bill justifies the need for a commemorative day with the following: “As one of the most diverse provinces in Canada, Ontario is recognized as an inclusive society. Ontario is also the home of one of the largest Asian populations in Canada. Currently, some Ontarians have direct relationships with victims and survivors of the Nanjing Massacre” (Wong 2016). On December 7, the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC), an organization formed in 1947 to seek redress for Japanese Canadian mass incarceration during the Second World War, issued a public statement of opposition to Bill 79. Nonetheless, a commemorative day was declared in Ontario in 2017 by a unanimously passed motion. The debate continues, however, as Member of Parliament Jenny Kwan has since twice called for a national commemorative day. Kwan has campaigned for the day since 2017, gaining the support of numerous community organizations, prominent Japanese Canadians such as Joy Kogawa, and the signatures of nearly 40,000 petitioners. Executive members of the NAJC have renewed their opposition, and the issue has opened up old conflicts and surprising allegiances within the Japanese Canadian community.

The NAJC’s letter of opposition to Bill 79, addressed to Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne, opens with an assertion of the NAJC’s position as a Canadian organization with uniquely Canadian concerns. It states, “the National Association of Japanese Canadians wishes to register its strong opposition to the Private Members Bill 79. We believe that the primary focus of all Ontarians should be on the improvement of race relations and civil rights within this province and indeed Canada” (Mitsui 2016). The letter dismisses Wong’s call for a commemorative day for the Nanjing Massacre because of its concern with “foreign” affairs, contrasting it with the NAJC’s Canadian focus (Mitsui). While we might reasonably ask about the purpose of a national commemoration for a historical event that occurred outside of the country, this is not an uncommon practice in Canada.1 Considering the numerous precedents for memorial days for international genocides, the NAJC’s concern that the bill “will open the floodgates for others seeking a platform for incidents that occurred outside of this country” seems belated (Mitsui). A close reading of the NAJC’s letter raises the question of why the organization opposes this specific commemorative measure, but not others. The NAJC also charges that the bill is “opposed to the provincial government’s belief in an inclusive, accepting society. It will promote hostility towards the Japanese Canadian community by the larger society, including increasing tensions between Asian Canadians. The bill, rather than promoting inclusion, will promote intolerance” (Mitsui). On what grounds can the NAJC make the claim that a commemorative day for the Nanjing Massacre contradicts Ontario’s purported inclusivity, and how do they imagine that the declaration of a commemorative day—rather than their own objection to it—will create conflict between Canadians, and “Asian Canadians” in particular?

I will argue that the NAJC’s opposition to the commemorative days derives from two contradictory aspects of the organization, and indeed, of the Japanese Canadian community as a whole. First, the NAJC’s attitude towards the commemoration efforts of other Asian diasporic communities in Canada is related to the limitations of the national politics of redress that the organization has promulgated. As with the Japanese American redress movement, Japanese Canadians fought for reparations for mass incarceration from the 1960s through to the campaign’s success in 1988. Since then, the NAJC has focused on education about Japanese Canadian incarceration as a means of improving Canadian “race relations.” But their letter to Premier Wynne raises the question of where the NAJC seeks to impose limits on commemoration for the purpose of promoting racial justice in Canadian society. I argue that the assumption of a narrow and “proper” Canadian citizenship—to borrow Roy Miki’s term—as part of the campaign that culminated in the 1988 Redress Agreement continues to shape Japanese Canadian politics today (Beauregard 2009, 77). Indeed, in order to foreground the Canadianness of the Japanese Canadian community and the NAJC, the organization has disavowed its complex, transnational composition. This disavowal is belied by the NAJC’s relationship to Japanese institutions and politics. By analyzing the material and ideological entanglement of the NAJC with the government of Japan, it becomes evident that the NAJC’s activities are influenced by Japanese right-wing politics. Indeed, the NAJC’s position on local political issues, such as the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day, have been thoroughly informed by the Japanese state’s growing denial of the violence of Japanese imperialism.

The paradox of, on the one hand, the NAJC’s transnational composition, and, on the other hand, the assumption of a “proper” Canadian identity, riddles the organization’s reactionary and seemingly nonsensical position on the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day. When confronting the efforts of other “Asian Canadians” to memorialize the violence of Japanese imperialism within Canada’s borders, the NAJC seeks to maintain the contradictory position of an authority on appropriately Canadian political and historical concerns, while also seeking to quash any critique of Japan because of ongoing Japanese Canadian relationships to Japanese institutions, politics, and communities. Through analysis of the NAJC’s rhetoric, history, and contemporary composition, I seek to develop a critique of the simultaneous nationalist structure and disavowal of transnationalism that structure the NAJC and impinge on the possibility of solidaristic affiliations between Japanese Canadians and other minoritized communities. In turn, I hope to illuminate some of the other possibilities for solidarity, reconciliation, and deimperialization that emerge from Japanese Canadians’ complex history.

The Politics of Redress and the Borders of Remembrance

In its current mission statement, the NAJC writes that it works “To promote and develop a strong Japanese Canadian identity and thereby to strengthen local communities and the national organization. To strive for equal rights and liberties for all persons – in particular, the rights of racial and ethnic minorities” (NAJC 2022). However, I will argue that the two sentences that constitute the mission statement underscore the limitations of an anti-racist politics that is circumscribed by the politics of national redress. The promotion and development of a singular “strong Japanese Canadian identity” is today being achieved at the expense of the second goal, to strive for equality and liberty among all racial and ethnic groups.

At the end of the list of points for consideration in the NAJC’s letter to Premier Wynne, a striking paragraph invokes the Japanese Canadian struggle for redress:

September 22, 1988 saw the successful redress settlement between the NAJC and the Government of Canada. There were those, such as the Royal Canadian Legion (Ontario Command), that opposed Japanese Canadian redress because they could not differentiate Japanese Canadians and the Japanese who carried out military operations in Asia. Similarly, we believe that the passage of Bill 79 will create “guilt by association” and anger will be directed towards the Japanese Canadian community (Mitsui).

While the letter’s earlier emphasis on the fact that the Nanjing Massacre was a “foreign” event serves to contrast Soo Wong’s claim for commemoration and the Japanese Canadian struggle for redress, in this reference to the redress campaign there is a peculiar mirroring. In opposing Chinese Canadians’ commemoration efforts, the NAJC cites opposition to their own fight for redress from veterans who refused to distinguish Japanese Canadians from the Japanese soldiers they fought in the Pacific Theater. The specter of “guilt by association,” or the racialized confusion of Japanese Canadians with the Japanese Imperial Army, goes unchallenged in this recapitulation. The possibility of the racist confusion of Japanese Canadians and Japanese nationals is extended into the present not to critique the persistence of racism in Canada, but to transform the NAJC’s opposition to the commemorative day into an appeal for state protection from these kinds of misrecognitions. The NAJC demands that Ontario’s Premier intervene in commemoration efforts that address international historical events, ostensibly to prevent a repetition of WWII-era anti-Japanese sentiment from harming contemporary Japanese Canadians.

The NAJC continues this line of reasoning in the conclusion to the letter: “On the anniversary of Pearl Harbour on December 7th, there are reports of our children being bullied on that ‘Day of Infamy.’ We do not need a special day to have our children victimized again” (Mitsui). It is unclear where these reports are coming from. As Emi Koyama points out, “Since the stories about the supposed “bullying” of Japanese children began appearing in conservative publications in Japan, many local, national, and international media outlets have tried to substantiate the claim but to no avail: schools, law enforcement agencies, Japanese American community groups, and others could not identify a single report of such bullying” (2016). Indeed, the rumor of Japanese diasporic children being bullied in response to commemorative measures that may be construed as critical of Imperial Japan appears to have originated in a 2012 news article about the first “comfort women” memorial to be established in the United States, in Palisades Park, New Jersey, published by right-wing journalist Okamoto Akiko in Seiron Magazine (Yamaguchi 2020, 6).2 Seiron and other like-minded publications have spearheaded Japanese historical revisionist movements in response to growing international recognition of atrocities committed by the Japanese Imperial Army and government. Japanese historical revisionists have been most vehemently opposed to efforts to commemorate and redress the Imperial Army’s sexual enslavement of women and girls from Korea, China, the Philippines, and other parts of Asia and the Pacific, as well as the Nanjing Massacre (Yamaguchi, 6).3 Tomomi Yamaguchi points out that while rumors of bullying were frequent following Okamoto’s 2012 report, there is no evidence for these claims (6). Other concerns about “anti-Japan” sentiment in the United States have since taken center stage, as right-wing media has identified the US as the shusenjo (主戦), or “main battle ground,” of the history wars (Yamaguchi, 6). In other words, in claiming that the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day will foment anti-Japanese racism in the form of schoolyard bullying, the NAJC parrots the rhetoric of Japanese historical revisionists.

The NAJC’s letter also states that “Canada has welcomed over 37,000 Syrian refugees—many to [Ontario]. The clear message of Bill 79 is that Canada will not be a safe sanctuary from the ethnic and religious conflict that forced their exile,” a point for which no further explanation is offered (Mitsui). It is not at all apparent what “clear message” a provincial day commemorating the Nanjing Massacre would send to Syrian refugees in Canada. Provincial and national remembrance days are not statutory holidays, they frequently pass unmarked in schools and workplaces, and they are not typically represented on calendars or in state ceremonies. What is curious about this passage is its decontextualized invocation of another population within Canada’s borders to object to Chinese Canadian efforts to commemorate the Nanjing Massacre. By aligning themselves with Syrian refugees against the threat of Chinese Canadian commemoration efforts, the NAJC constructs a racial logic by which the letter proceeds: it formulates a series of racial-national binaries, the interaction of which always result in the representation of Japanese Canadians as the most Canadian subjects. These binaries are first the Royal Canadian Legion, who considered Japanese Canadians “guilty by association”; Chinese Canadians, who fail to support the improvement of all Canadians’ “race relations”; and Syrian refugees in Canada, who are threatened by Chinese Canadian commemoration efforts. The Royal Canadian Legion and Chinese Canadians are constructed as sharing the same misidentification of Canadian political issues with military histories in Asia. In contrast, Japanese Canadians are likened to Syrian refugees; a vulnerable and persecuted minority whose safety rests on the state’s careful management of national memory and culture. Japanese Canadians and Syrian refugees are, in this logic, proper and deserving members of Canadian society, while Wong and other Chinese Canadians who support the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day are positioned as a threat to the nation because of their international concerns.

By this formulation, Japanese Canadians—and, apparently, Syrian refugees—support a progressive state that overcomes its own past injustices and extends refuge to others fleeing injustice. Crucially, the NAJC implies that through redress and education, Japanese Canadians support the state in leaving behind its historic injustices. By contrast, the letter suggests that Chinese Canadians challenge the borders of the state by demanding that it commemorate international historic events annually in perpetuity. Rather than providing a means of overcoming the violence of the Nanjing Massacre, the commemorative day would, the NAJC’s letter suggests, perpetuate it, importing it to Canada and undermining the progress of the Canadian “equal rights and liberties” (NAJC 2022).

Japanese Canadian redress was the first formal apology issued by the Canadian federal government, followed by apologies to Indian Residential School survivors and Chinese Canadians for the Chinese Head Tax, among others. The Redress Agreement is therefore frequently celebrated as the precedent that paved the way for other measures for redress and reconciliation (McElhinny 2016, 56). However, the Canadian state’s practice of apologizing for past injustices and seeking “reconciliation” with Indigenous peoples has been roundly critiqued for the ways in which it strengthens the state’s own legitimacy, positioning it as a progressive power always moving closer to multicultural democracy.4 Beyond foreclosing the more radical possibilities of social justice struggles, the politics of redress also confines the scope of social justice issues to the nation-state’s borders. As Tatsuo Kage notes, the struggle for redress was a moment in which Japanese Canadians defined the injustice of incarceration as having to do strictly with the violation of citizenship rights. In his writing about the mass deportation of 3,946 “disloyal” Japanese Canadians in 1946, and the relative obscurity of this aspect of the mass incarceration of Japanese Canadians, Kage notes:

Most of us heard about “repatriation” or “deportation,” but it was rarely talked about during our redress campaign in the 1980s. Perhaps this was because our campaign emphasized the Canadian nature of the issue, in other words, we raised the issue of unjust treatment of Canadian citizens by the government, and we demanded amendments of the wrongs done to Japanese Canadians in Canada. Therefore, activists in the Redress campaign in Canada had little interest in people in Japan even though their experiences could have been even more serious or aggravated (Kage 2012).

Likewise, Roy Miki discusses the redress campaign’s failure to seek apologies and compensation for Japanese Canadians who were deported to Japan in 1946 during the struggle for redress. Unlike in the United States, upon the closure of the incarceration camps in 1945, the Canadian government forced Japanese Canadians to either relocate to the east or “volunteer” to be “repatriated” to Japan. Many “agreed” to be deported under coercion or confusion, and many struggled in post-war Japan (Kage). Miki writes that the NAJC “had been so intent on impressing on Canadians the hyper-Canadian nature of its human-rights cause that it had unintentionally disavowed its responsibility to the Japanese Canadians living in Japan. We had missed the transnational implications of redress” (Miki 2013, 265). Rather than simple oversight, I argue that these were strategic political sacrifices that the NAJC made so that its demand for recognition would be legible to the state. The appeal for redress circumscribed Japanese Canadian politics such that compensation and apologies for those living in exile in Japan were beyond consideration. Further, this neglect “confirmed the complicated and at times highly conflicted transnational ties that Japanese Canadians had with Japan before the war” (Miki, 2013, 265). I wish to extend Miki’s observations about the transnational composition of the Japanese Canadian community to today’s debate surrounding the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day. It is clear from the NAJC’s opposition that these transnational ties persist, but even more, that they have been strengthened and institutionalized in the structure of the post-redress NAJC. Contrary to the NAJC’s representation of itself as purely Canadian, its transnational ties are not severed by state recognition and redress, and they act as persistent forces in Canadian politics.

Transnational Politics, Local Implications

Member of Parliament Jenny Kwan made a second demand for the declaration of a national Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day in the House of Commons on November 28, 2018. Urging Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to declare the day, Kwan said, “December 13 marks the eighty-first anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre. In recognition of crimes against humanity and in the spirit of never again, I am calling on the government to declare December 13 of every year as Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day” (Parliament of Canada 2018). Skirting the demand for an official declaration for the second year in a row, Trudeau replied, “Of course we deplore the horrific events that took place in Nanjing eighty years ago. All Canadians can agree that the loss of life and violence that so many civilians faced should never be forgotten. We will never forget those terrible acts. The memory of these victims and survivors must be addressed in the true spirit of reconciliation” (Parliament of Canada).

Kwan’s demand and Trudeau’s response both name the “spirit” of distinct but related logics in Canadian politics, represented by “never again” and “reconciliation.” Kwan’s “never again” makes reference to the Holocaust as an exceptional historical injustice and the resultant development of human rights law, which was itself foundational to the Japanese Canadian struggle for redress.5 Meanwhile, “reconciliation” has become a household term in Canada following the 2006 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, the 2008-2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, and the 2018-2019 National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. Trudeau’s response to Kwan, which substitutes the “spirit of reconciliation” for the “spirit of never again,” implies that while adjacent, these two spirits conflict. Trudeau’s statement suggests that the national commemorative day for the Nanjing Massacre might not address this history and Chinese Canadian attachments to it in the “spirit of reconciliation,” which, during Trudeau’s tenure as Prime Minister, has consisted of a set of policies that mitigate Indigenous land claims, treaty rights, and other challenges to the Canadian state’s political and economic interests. Trudeau’s administration has sponsored the construction of pipelines and other resource extraction projects that violate the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), and has been roundly criticized for its failure to enact substantive change in the wake of the findings of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, let alone the ongoing discovery of unmarked, mass graves at the sites of former residential schools beginning in spring 2021.6 In other words, the Trudeau administration’s “reconciliation” politics have sought to quell Indigenous-led uprisings and political unrest, while bolstering the power and legitimacy of the settler colonial state. We might surmise, then, that by invoking the “true spirit of reconciliation” in response to Kwan’s arguments in the House of Parliament, that Trudeau perceives a challenge to the state in the proposed national Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day.

Indeed, throughout 2017 and 2018, when Kwan twice proposed the commemorative day, Trudeau and other members of his government were in negotiations with ten other “Pacific nations”—Australia, Brunei, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam—to finalize the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Following the United States’ withdrawal from the deal in 2017, Canadian negotiators conceived of the agreement as an opportunity to gain a competitive edge over countries not included in the CPTPP, especially the United States, and the urgency to finalize the agreement was heightened. The Canadian Agri-Food Trade Alliance (CAFTA), one of the primary Canadian beneficiaries of the CPTPP, and Jim Carr, International Trade Diversification Minister at the time of the agreement, named the increased access to Japanese markets as the primary gain of the CPTPP. CAFTA states that, “Japan, as the third-biggest export market, is the big prize for Canadian agri-food exporters in the CPTPP” (CAFTA, 2022a). The cheerfulness with which CAFTA celebrates trade with Japan is entirely absent from its description of trade relations with China, which, they state “require that a number of issues be addressed” (CAFTA, 2022b). At the same time, Canada’s diplomatic relationship with China was steadily deteriorating during the CPTPP negotiations, in large part due to Canada’s role in the 2018 arrest and extradition case of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou, and the subsequent arrest of two Canadians—former diplomat Michael Kovrig and business consultant Michael Spavor—on espionage charges that were understood by many Canadians as retaliatory. While Kovrig and Spavor were released in September 24 2021, tensions over China’s September 16, 2021 bid to join the CPTPP continue, with Japan urging the US to join the CPTPP in response (Okutsu 2021).

Trudeau had several meetings with former Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo before the ratification of the CPTPP in 2018 in Tokyo, directly between Jenny Kwan’s two calls for a national Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day. In September 2, 2020, the Prime Minister’s office released a memo that details how Trudeau recently “commended Prime Minister Abe’s efforts to promote a free and open Indo-Pacific region, which advances our shared values and commitment to multilateralism and a rules-based international order,” referencing contemporaneous conflicts in the East China and South China seas between China and surrounding countries, including Japan (Prime Minister of Canada 2020). During and prior to this time, Abe was also playing an active role in the “history wars.” For his 2012 election campaign, Abe ran on a platform that included reversing the statements of previous Japanese officials, including the 1993 “Kono Statement,” which acknowledged the “comfort women” issue (Yamaguchi, 5). Abe had active affiliations with far right organizations, which included making appearances at their rallies and events, revising history textbooks, and signing his name to paid advertisements to spread historical revisionist propaganda in the US (Yamaguchi, 7).

Meanwhile, numerous Canadian news outlets reported Japanese lobbyists approaching Ontario Members of Provincial Parliament (MPP) prior to the passing of Soo Wong’s motion to declare a provincial commemorative day in 2017. An October 2017 article in The Toronto Star reports that NDP MPP Peter Tabuns received “strange postcards from Japan” at his office, and that “Premier Kathleen Wynne herself was lobbied by those sympathetic to the Japanese version of events” (Benzie 2017). The article continues, “‘There have been emails to some of us from Japanese lawmakers in the Diet in Tokyo,’ confided one senior Liberal” (Benzie). These reports are nearly identical to those that have emerged from other hotbeds of the “history wars.”7

While pressure from the Japanese government may have been the primary cause for Trudeau’s resistance to the declaration of a federal Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day, the NAJC was still a vocal player in the controversy. Satoko Oka Norimatsu elaborates on the complexity of the various parties involved in the conflict surrounding the commemorative day, who are rather imprecisely captured by terms like “Japanese,” “Chinese,” or “Asian,” by noting that while Kwan didn’t garner the broad Chinese Canadian support she had hoped for—her petition fell 60,000 signatures short of her goal of 100,000—“Chinese-language media in Canada gave the issue extensive coverage” (Riches 2019). Norimatsu continues to note that “Ironically, those that appeared passionately interested in this issue were the opposition group that consisted of Japanese immigrants and Japanese Canadians, and the Japanese-language newspapers in Canada” (Riches).

The NAJC’s participation in the controversy, while rooted in the focus on the nationalistic politics inaugurated by the struggle for redress, has everything to do with transnational politics. The NAJC frequently collaborates with the Japan Foundation, an organization established and funded by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the promotion of the study and appreciation of Japanese history, culture, and language overseas. The Japan Foundation funds NAJC programming, especially for events like Japanese language programs, book talks, and film screenings. Further, Norimatsu points out that some members of the NAJC’s leadership have had longstanding and persistent relationships with Japanese government officials and organizations. Former NAJC president Gordon Kadota had a close relationship with Okada Seiji, then Consul General of Japan in Vancouver, and he took a prominent role in opposing the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day (Norimatsu 2020, 4). In the years prior to the controversy over the commemorative day, Kadota was also vocally opposed to the proposed “comfort women” memorial in Burnaby, BC and was instrumental in organizing sections of the Japanese Canadian community in opposition to it. Japanese officials and activists have not only lobbied Canadian provincial and federal representatives; they also play a determinative role in the NAJC’s position on the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day. Another irony of the controversy, then, is the fact that while the NAJC seeks to position itself as an organization with singularly Canadian concerns, its position on “Asian Canadian” political issues is thoroughly informed by Asian politics, especially the increasingly revanchist politics of the Japanese government.

Reconciliation Within and Beyond Japanese Canadians

In a speech delivered at a press conference in Ottawa alongside Jenny Kwan on November 28th, 2018, and later mailed in letter form to Trudeau, prominent Japanese Canadian poet and novelist Joy Kogawa voiced her support for the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day. Explicitly linking the history of redress to the need to carry on its legacy in the commemoration of the Nanjing Massacre, Kogawa said, “I am humbled by the support Japanese Canadians received as Asian Canadians stood together as one with us in our struggle and in celebration. That is one reason I am here, as a Japanese Canadian, to support Jenny Kwan and to thank those who stood with Japanese Canadians as we labored to have our story known” (Kogawa 2018). In contrast to the NAJC, this invocation of the struggle for redress, and the broad Asian Canadian solidarity that supported it, is the reason to support the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day. Rather than highlight those who opposed redress, Kogawa emphasizes the diverse groups who supported it beyond members of the Japanese Canadian community itself.

Besides Kogawa, numerous other Japanese Canadians have been vocal in their support for the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day. These include ad hoc groups revolving around the NAJC’s Young Leaders Committee and Japanese Canadians Supporting Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day, a group that was formed in 2018 to support Kwan’s calls for a national commemorative day. On February 14, 2017, another group of Japanese Canadians submitted a collectively authored letter, titled “Withdraw NAJC Opposition to Bill 79” to the NAJC. Signed by 93 self-identified “Japanese, Japanese Canadian, and Nikkei people,” the letter makes an incisive critique of the NAJC’s 2016 letter to Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne. Like Kage, Miki, and Norimatsu, the letter points out the transnational constitution of the NAJC as a reason to support, rather than oppose, the commemorative day:

The NAJC claims to be inclusive of, and therefore to represent, both “established” and “post-war” Japanese communities in Canada. Our communities and organisations have prioritised the integration of post-war “imin” or “ijuusha” (immigrants) from Japan, and have also worked closely with organisations based in post-war Japan, including the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The NAJC’s insistence, then, that this issue is a “foreign” one, and that Japanese Canadian communities should not be “associated” with “the Japanese who carried out military operations in Asia,” conveniently ignores how our communities are already connected to, inclusive of, and benefitting from the Japanese inheritors of legacies of war in Asia (emphasis in original).

The letter refuses to understand Japanese Canadian communities and organizations as national rather than transnational groupings, pointing to how the boundaries between “Japanese” and “Canadian” have never been fixed in the diaspora. The emphasis on the heterogeneity of Japanese Canadian communities, including “established” and “post-war” immigrants, disrupts the NAJC’s representation of a bounded Canadian population that has been entirely shaped by the shared experience of incarceration and redress. The letter also asserts that, through sustained and lucrative ties with the Japanese government, the NAJC and Japanese Canadian communities are beneficiaries of historic Japanese imperialism. We might add that, in reproducing itself through funds from the Japanese government, the organization also benefits from ongoing US imperialism in Asia and the Pacific, which facilitated Japan’s postwar economic rehabilitation. Whether through collaboration and funding procured from the government of Japan or by the “shoring up” of citizenship in the Canadian state, the letter implies that “Japanese Canadian,” as identity, nationality, and institutionalized political-cultural grouping has been wrought from multiple imperialist and colonial histories. The letter does not demand that the NAJC cut ties with the Japanese government, or desist from receiving funds from it; instead, it suggests ways in which Japanese Canadians might mobilize their complex position as both survivors of mass incarceration and as beneficiaries of Japanese imperialism towards solidaristic ends.

For instance, like Kogawa, in this letter it is the legacy of Japanese Canadian redress that “urgently reminds us, as Japanese Canadians, of our responsibility to join with others in their struggles for justice.” Rather than making Japanese Canadians legitimate citizens in need of protection from further exclusion, Japanese Canadian history reminds us of the support of Chinese and Korean cultural associations and indigenous peoples, among others, for the struggle for redress. The letter continues:

What is most disturbing about the NAJC’s opposition to Bill 79, however, is its use of the rhetoric of marginalisation to silence others in their struggles for justice. By arguing that Bill 79 will “promote intolerance” against Japanese Canadians, the NAJC misleadingly characterises justice as a zero sum game, a politically hopeless scenario where the demands of one marginalised group can only be met at the expense of another’s. Likewise, calls to “[celebrate] accomplishments” and “reject all violence and wars” instead of supporting Bill 79 echo the kind of politically vague and deflective sentiments that the NAJC itself faced while demanding redress for internment (emphasis in original).

Refusing the inclusion of Japanese Canadians in the state at the price of the exclusion of others, the letter offers a searing critique of institutionalized Japanese Canadian politics as represented by the NAJC. In closing, the letter articulates its own vision of “reconciliation,” one that counters Trudeau’s “true spirit of reconciliation” and offers an alternative even to Kwan’s “never again”:

We understand that the issues at play here are complex, and that being associated with the pain and trauma of others is uncomfortable—especially in light of our own painful and traumatic histories. We accordingly do not imagine a simple solution. A first step might be to engage in sincere conversations with other community and advocacy groups about how legacies of war implicate our diverse communities, without giving in to the temptation to flatten real differences across experiences of injustice. Such conversations may engender new understanding, creating opportunities for reconciliation and shared struggle for justice. But none of this can begin while the NAJC aligns itself so wholly and unjustifiably against those with whom it needs to be in dialogue. We therefore urge you to withdraw your opposition to Bill 79, and to commit to the difficult but necessary work of reconciliation that lies ahead (emphasis in original).

The letter offers a vision of reconciliation that is indivisible from a “shared struggle for justice.” In so doing, it tasks the NAJC with confronting its position as a potential beneficiary of past injustice, with all of the “pain and trauma” that entails. It also tasks the NAJC with taking its own mandate seriously by throwing its structural and financial weight behind, rather than against, contemporary struggles for justice in Canada.

Much like the letter writers, Chen Kuan-Hsing, a scholar of inter-Asian cultural studies, theorizes reconciliation as a “working through” of repressed colonial and imperial pasts, a willingness on the part of colonizers to “shoulder responsibility for the past,” and a “mutual effort to understand each other’s emotional and psychic terrain” at the level of nations, races, ethnic groups, and families (2010, 4). However, any possibility of reconciliation must, in Chen’s formulation, be preceded by a process of “deimperialization” (4). As the inverse of decolonization, deimperialization is “work that must be performed by the colonizer first, and then on the colonizer’s relation with its former colonies. The task is for the colonizing or imperializing population to examine the conduct, motives, desires, and consequences of the imperialist history that has formed its own subjectivity” (4). While Chen is thinking specifically of regional reconciliation in Asia, this theorization is relevant to the one forwarded by the authors of the “Withdraw NAJC Opposition to Bill 79” letter, who suggest that Japanese Canadians too must engage in the “painful and reflexive” work of deimperialization and reconciliation (Chen, 4). This is, perhaps, the most objectionable element of the NAJC’s position; it rests on an utter unwillingness to examine the history through which it was produced, and to be conscious of, let alone accountable for, the ramifications of that history. Chen concludes his discussion of reconciliation with the following: “If attempts to engage these questions are locked within national boundaries, we will never break out of the imposed nation-state structure. If critiques remain within the limits of the nationalist framework, it will not be possible to work toward regional reconciliation” (Chen, 159). The “difficult but necessary work of reconciliation” that the Nikkei letter writers urge the NAJC towards also seeks historical contextualization of contemporary conflicts that trace their roots back to colonial and imperial structures—even those that lie beyond, and indeed undermine, today’s nation state formations.

The “Withdraw NAJC Opposition to Bill 79” letter stretches the boundaries of political concerns in Canada across national and cultural borders. A future letter might also call for grassroots Japanese Canadian support for struggles against historic and contemporary Japanese and US imperialism in Asia. These include efforts to redress the “comfort women” in Korea, China, and the Philippines; memorialization efforts for Vietnamese victims of the Vietnam War, and struggles against US imperialism in Okinawa, the Marshall Islands, the Philippines, and beyond. Japanese Canadians might also seek organizational structures beyond the NAJC’s, which, alongside its entanglement with Japanese right-wing politics, has since its inception been defined by issues stemming from incarceration that limit its political orientation, past and present. It might look beyond the narrow terms of Canadian political debate, replete as it is with unfulfilled promises and reiterative apologies, to a critical understanding of reconciliation, or to an altogether different process for seeking justice. And, it might take further inspiration in the direction it shifts our imagination of justice towards; to a space as wide as the Pacific Ocean, as mobile as the many peoples who have traversed it for generations.

Coda: The Past is Present

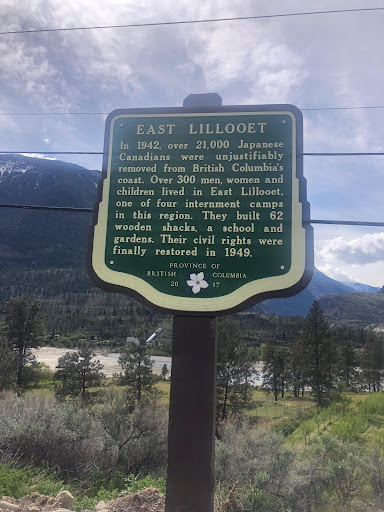

Image 1. One of nine “Japanese Canadian internment signs” erected by the British Columbia government in 2017 and 2018 at the sites of former incarceration and work camps.

Photograph by the author.

Jenny Kwan’s campaign for a national Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day appears to have stalled since 2018. Since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020—with its attendant housing and employment crises—the MP has intensified her focus on issues to do with poverty and the opioid crisis, as well as immigration and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. Nonetheless, Chinese Canadian organizations including the Confederation of Toronto Chinese Canadian Organizations, Canada ALPHA (Association for Learning and Preserving the History of WWII in Asia), and BC ALPHA continue to memorialize the Nanjing Massacre. Meanwhile, a new Japanese Canadian campaign for redress launched in 2019 has succeeded. While it seems to have faded from domestic politics for the time being, the transnational terms of the debate surrounding the Nanjing Massacre commemorative days are still relevant to the politics of redress and commemoration within and beyond Asian Canadian communities. What’s more, the absence of a resolution for the controversy around the Nanjing Massacre commemorative days points to the ongoing need for deimperialization and decolonization within and between these communities.

In 2019, a newsletter circulated by the Greater Vancouver Japanese Canadian Cultural Association (GVJCCA) announced a new Japanese Canadian redress struggle and invited community members to participate in consultations taking place across the country. Following on the British Columbia Provincial Government’s 2012 apology for the role that it played in Japanese Canadian mass incarceration, the GVJCCA and the NAJC formed the BC Redress Negotiations Committee to demand more than an apology from the BC government. At that time, the NAJC elaborated on the need for this second redress campaign: “The Government of British Columbia issued an official Apology Motion to Japanese Canadians in 2012. The BC Government did not formally quantify or assume responsibility for past injustices, and the apology was not followed by redress or legacy initiatives at the time, which many saw as a missed opportunity for meaningful follow-up and healing. ” (BC Redress 2022c). Following community consultations and negotiations with the provincial government led by the NAJC in 2019 and 2020, in 2021 $2 million was granted by the government to create the Japanese Canadian Survivor Health and Wellness Fund (BC Redress 2022a). Finally, on May 21, 2022, BC Premier John Horgan announced a further $100 million redress package, which will fund initiatives for “anti-racism; education; heritage; monument; community and culture; and especially seniors’ health and wellness” (BC Redress 2022b).

Image 2. Nanjing Massacre Victims Monument at Elgin Mills Cemetery in Richmond Hill, Ontario during its 2018 unveiling (Xinhua News Agency via CTGN, accessed August 1, 2022).

On December 9, 2018, the Nanjing Massacre Victims Monument was unveiled at the Elgin Mills Cemetery in Richmond Hill, Ontario. The monument is the only monument to the Nanjing Massacre outside of China, and the unveiling was attended by 1000 people, including Jenny Kwan, Soo Wong, and a number of other members of the provincial and federal government. While the ceremony received almost no coverage in Canadian news media, it was widely reported and celebrated in English-language Chinese media, including Xinhua, China Daily, and China Global Television Network. Attendees laid white roses and wreaths bearing purple flowers on the monument, which reads: “Remember History, Pray for Peace.”

Related APJJF Articles

Satoko Oka Norimatsu, “Canada’s ‘History Wars,’: The ‘Comfort Women’ and the Nanjing Massacre”

Tomomi Yamaguchi, “The ‘History Wars’ and the ‘Comfort Women’ Issue: Revisionism and the Right-Wing in Contemporary Japan and the U.S.”

References

Toronto City Council. “Agenda Item History – 2016.MM23.3,” 2016.

BC Redress. “BC Redress Timeline,” 2022a.

———. “BC Redress,” 2022b.

———. “Internment Era Timeline,” 2022c.

Beauregard, Guy. “After Redress: A Conversation with Roy Miki.” Canadian Literature, no. 201, 2009, pp. 71-86.

Benzie, Robert. “MPPs Unanimously Pass Motion to Commemorate Victims of Nanjing Massacre.” The Toronto Star, October 27, 2017.

Canadian Agri-Food Trade Alliance. “Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP),” 2022a.

———. “Canada and China,” 2022b.

Chen, Kuan-Hsing. Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization. Duke University Press, 2010.

Kage, Tatsuo. “Tatsuo Kage: Chronicling Japanese Canadians in Exile.” National Association of Japanese Canadians, 2012.

Kogawa, Joy. “Author Joy Kogawa writes to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau seeking support for Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day.” The Georgia Straight, December 13, 2018.

Koyama, Emi. “Has the Establishment of “Comfort Women” Memorials in the U.S. Led to Widespread Bullying Against Japanese Children?” Japan-U.S. Feminist Network for Decolonization, April 10, 2016.

McElhinny, Bonnie. “Reparations and racism, discourse and diversity: Neoliberal multiculturalism and the Canadian age of apologies.” Language & Communication, vol. 51, 2016, pp. 50-68.

Miki, Roy. “Rewiring Critical Affects: Reading ‘Asian Canadian’ in Transnational Sites of Kerri Sakamoto’s One Hundred Million Hearts.” Reconciling Canada: Critical Perspectives on the Culture of Redress. Eds. Jennifer Henderson and Pauline Wakeham. University of Toronto Press, 2013.

Mitsui, David R. “Bill 79 Day to Commemorate the Nanjing Massacre.” National Association of Japanese Canadians, December 7, 2016.

National Association of Japanese Canadians. “Mission Statement,” 2022.

Norimatsu, Satoko Oka. “Canada’s ‘History Wars’: The ‘Comfort Women’ and the Nanjing Massacre.” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, vol. 18, no. 6, 2020, pp. 1–18.

Okustu, Akane. “Japan foreign minister calls for U.S. to join CPTPP,” Nikkei Asia, October 23, 2021.

Parliament of Canada. “42ND Parliament, 1st Session, Edited Hansard Number 360, Wednesday, 28 Nov, 2018.”

Prime Minister of Canada. “Prime Minister Justin Trudeau Speaks with Prime Minister of Japan Shinzo Abe,” 2020.

Riches, Dennis. “Interview with Japanese Peace Activist and Author, Satoko Oka Norimatsu.” Lit by Imagination, 2019.

“Withdraw NAJC Opposition to Bill 79,” February 14, 2018.

Wong, Soo. “Bill 79, Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day Act, 2016.” Legislative Assembly of Ontario, 2016.

Yamaguchi, Tomomi. “The ‘History Wars’ and the ‘Comfort Woman’ Issue: Revisionism and the Right-Wing in Contemporary Japan and the U.S.” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, vol. 18, no. 6, 2020, pp. 1–23.

Notes

Nationally, there are commemorative days for five genocides: the Armenian Genocide, the Holodomor, the Holocaust, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Srebrenica Genocide. In terms of national histories of genocide, in 2021 September 30 was designated National Day of Truth and Reconciliation, as part of broader federal campaigns to deal with the legacy of Canadian settler colonialism, especially the history of the residential school system.

Struggles over memorials for “comfort women” in Canada, such as the memorial proposed, but never constructed, for the city of Burnaby, British Columbia, in many ways resemble their American counterparts, as suggested in Satoko Oka Norimatsu’s article, “Canada’s ‘History Wars’: The ‘Comfort Women’ and the Nanjing Massacre.”

For further reading on the ongoing struggles for justice and redress for survivors of the Japanese military’s institutions of sexual slavery, see The Transnational Redress Movement for the Victims of Japanese Military Sexual Slavery, edited by Pyong Gap Min, Thomas R. Chung, and Sejung Sage Yim; Denying the Comfort Women: the Japanese State’s Assault on Historical Truth, edited by Nishino Rumiko, Kim Puja, and Onozawa Akane; and East Asia Beyond the History Wars: Confronting the Ghosts of Violence, edited by Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Morris Low, Leonid Petrov, and Timothy Y. Tsu.

For a thorough critique of Canadian reconciliation politics, see Glen Coulthard, Red Skins, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. For a discussion of the “politics of recognition” in the Australian context, see Elizabeth Povinelli, The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism.

For a theorization of “never again” and human rights discourse, see Robert Meister’s After Evil: A Politics of Human Rights. Other organizations that advocate for the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day, such as Canada ALPHA (Association for Learning and Preserving the History of WWII in Asia) and its British Columbia chapter, BC ALPHA, also frequently link their motivation to Canada’s ample recognition of the horrors of the Holocaust, and they state that they seek a kind of parity in terms of recognition for the atrocities committed during the Pacific War.

For just a few examples, see Brent Patterson, “Trudeau Breaking UNDRIP Promise Brings Warning of Twenty Standing Rocks”; Gib van Ert, “Why Aren’t We Talking about the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples?”; Liam Midzain-Gobin, “The Pace of Reconciliation Has Been Slow Violence”; Saima Desai, “A Pipeline to Regret”; Courtney Skye, “The Canadian state seems like an immovable object. But Indigenous women are an unstoppable force.”

For example, in response to the 2012 establishment of a comfort woman memorial plaque in Palisades Park, New Jersey, two separate delegations of members of Japanese Parliament travelled to meet with the city’s mayor and other officials, offering cherry blossom trees, library books, and other donations should they agree to remove the plaque, and even arguing that “comfort women” were not enslaved. See Kirk Semple, “In New Jersey, Monument for ‘Comfort Women’ Deepens Old Animosity.”