Abstract: The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on love, marriage and family life. Employing both social science and cultural studies perspectives, this article discusses romantic and familial relationships and their respective depictions in four Japanese romantic dramas (ren’ai dorama) produced under pandemic conditions. It touches upon the COVID-19 pandemic and related policies in Japan, elaborates on conditions of TV production during the pandemic, and asks: How have TV series addressed love, dating and (marital) relationships during the pandemic? How did the pandemic and concomitant policies impact depictions of these topics? Finally, what do these dramas reveal about the state of domestic gender relations and gender equality in the context of changing working conditions and stay-at-home policies implemented during the pandemic? The article identifies a trend consistent with ‘re-traditionalization’ on the one hand, and depictions of diverse, unconventional relational practices that are critical of the marital institution on the other. While the dramas touch on the impact of the pandemic on women’s livelihoods and gender equality, more serious consequences remain unexplored.

Keywords: TV drama, COVID-19, love, relationships, marriage, gender

Note: The authors have contributed equally to this article; names appear in alphabetical order.

Introduction: Love, Dating and Marriage in the Pandemic Era (and Beyond)

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the ways in which people across the globe interact and socialize. Navigating dating and relationships becomes particularly fraught during periods of lockdown or social distancing, when the typical activities of couples, such as visiting cinemas, bars or restaurants, as well as physical intimacy between those not living in the same household, are either prohibited or discouraged. For a nation like Japan, which has seen a steady shift towards delayed marriage and long-term or permanent singlehood, the pandemic presented another potential obstacle for those looking for a relationship or lifetime partner: while marriage continues to be the (idealised) norm for most—89% of women and 86% of men want to get married at some point in their life—the proportion of unmarried adults who report being in a relationship is extremely low (27% of women, 20% of men; 18–34 years; IPSS 2017: 13, 22) and “not finding an appropriate partner” is the most cited reason for not being able to get married (women 51%, men 45%; IPSS 2017: 19).

In the context of these changes in dating and marriage behaviour (and against the backdrop of the falling birth-rate), the buzzword “marriage hunting” or “the active search for a marriage partner” (konkatsu) began to receive significant attention (Yamada & Shirakawa 2008) and the commercial matchmaking industry started to boom around 2010 (Dalton & Dales 2016). At around the same time, Japanese local communities and municipalities joined forces to support the institution of marriage in society and began to officially organise and promote matchmaking events (Kottmann 2020). This initiative was one of the state’s latest efforts to promote and encourage marriage behaviour: numerous countermeasures since the 1990s, such as the expansion of kindergarten and day care offerings for children below the age of three, as well as policies to enable parents to take childcare leave and other strategies aimed at improving the overall work-life balance, have been implemented, mainly in order to encourage women, who (still) shoulder the lion’s share of inner-familial care work, to get married and start a family, ideally early on in their adult life. Despite these efforts, the number of temporarily1 or permanently2 unmarried individuals continues to increase and life courses, which were centred on the salaryman husband/fulltime housewife model during the years of high economic growth in post-war Japan, are diversifying. The reasons are multidimensional and include, but are not limited to, an increase in precarious employment for men, improved education and employment opportunities for women, a (gendered) mismatch in expectations with regard to married life and gendered differences in what individuals consider an ‘appropriate’ partner or an ‘ideal’ life plan.

Life choices and the romantic and marital relationships of young urban individuals have long been a central topic of Japanese TV series. Since the 1980s, lifestyle-oriented ren’ai dorama (love story dramas) have connected with contemporary social discourses around love and familial relationships, gender roles and, more recently, (female) singlehood (Gössmann 2000 & 2016; Iwata-Weickgenannt 2013; Scherer 2016). These (mostly) limited-series dorama, which are primarily aimed at women, are broadcast for three months and each consist of about 10–12 one-hour episodes. Well-known examples from the last two decades include Around 40 (TBS, 2008) or Kekkon Shinai (English title: Wonderful Single Life, Fuji TV, 2012).3 As Kelly Hu points out, dorama highlight the diversity of life choices and encourage viewers to reflect on their own identities: “Japanese TV dramas present a multitude of similar questions with choices acted out for the viewers” (Hu 2010, 196). But how does this reflexive function operate within the context of the ongoing pandemic? How did television production companies deal with the problematic of producing a series under pandemic conditions? In particular, this article aims to address the following questions: How have TV series addressed love, dating and (marital) relationships during the pandemic? How did the pandemic and concomitant policies such as calls for social distancing (sōsharu disutansu) and self-restraint (jishuku) impact depictions of love, dating and (marital) relationships? Finally, what do these dramas reveal about the state of domestic gender relations and gender equality in the context of changing working conditions and stay-at-home policies implemented during the pandemic?

Employing both social science and cultural studies perspectives, we will discuss romantic and familial relationships and their respective depictions in four ren’ai dorama that are among the first to be produced under pandemic conditions, namely Rimorabu,4 Nigehaji Special,5 Neechan no Koibito6 and Koisuru Hahatachi.7 Although these were not the only dramas to be produced under pandemic conditions, due to space limitations, we have chosen to focus on dramas that aired during ‘prime-time’ (7 p.m. to 11 p.m.) on national terrestrial channels, which have the broadest reach in terms of audience. All of these ‘pandemic dramas’ were broadcast on Japanese television between October 2020 and early January 2021. TV series from this period are of particular interest: the series had already been planned before the outbreak of the pandemic, but the producers were subsequently forced to quickly adapt production conditions and scripts to the new situation. To achieve this, production teams chose different strategies, as we will show: some moved the story completely to the pandemic period and actively addressed many of the associated problems, including those regarding romantic and familial relationships. Others relegated COVID-19 to the background, for example through the appearance of extras wearing masks. Three of the examples we address belong to the typical, three-month Japanese series (renzoku dorama), and one—Nigehaji Special—is a television film (supesharu dorama) that is a follow-up to a hit series.

In the following, we will first briefly address the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan, related policies and the social consequences for various relationship forms. Then we describe the conditions of TV production during the pandemic, before examining in the main section how love, dating and (marital) relationships in the time of the pandemic are portrayed in the four selected Japanese TV dramas. Our analysis shows both a trend consistent with ‘re-traditionalization’, in the sense that the pandemic made pre-existing, pervasive gender inequalities visible and worsened them, and depictions of diverse, rather unconventional relational practices that are critical of the marital institution. Our analysis also shows that, while the dramas touch on the impact of the pandemic on women’s livelihoods and gender equality, more serious consequences remain unexplored.

The Pandemic, Concomitant Policies and Changing Love and Family Life in Japan

As in many other countries around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in Japan in early February 2020, making a significant impact on individuals’ relationship worlds, including the need to renegotiate and re-evaluate social and physical proximity and distance. The first cases were transmitted by infected passengers of the Diamond Princess, a cruise ship that landed in Yokohama with approximately 3,700 crewmembers and passengers, one of whom tested positive for the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) (NIID 2020). By mid-February, the first precautionary measures had been issued, including, for example, the cancellation of large-scale events. In addition (and following the decision to postpone the Olympics), then-Prime Minister Abe Shinzō closed national borders on 3 April 2020 and declared the first state of emergency (SoE) for seven prefectures on 7 April 2020. Seven days later, this SoE, which led to temporary closures of restaurants, cafés, department stores, museums and elementary schools, but not a strict lockdown as in other countries, was extended to the entire nation. It was lifted in late May and life returned to a ‘new’ or ‘adjusted normalcy’ (Togo 2020). Yet, after a surge in COVID-19 cases in late 2020, a second SoE was eventually implemented in selected prefectures on 7 January 2021 (until 21 March). Amidst another increase of cases, some parts of the country, including Osaka and Tokyo, entered a third SoE in late April that year (terminating on 20 June 2021). A fourth SoE was implemented in mid-July (and ended on 12 September 2021) and a fifth in early 2022 (lifted on 21 March 2022) (Kottmann & Dales forthcoming).

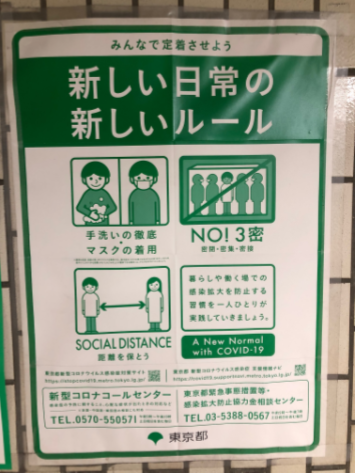

In addition to the SoEs and their varying regulations as well as foci on the detection of clusters and the enhancement of early diagnosis of patients, there were attempts from the very outset of the pandemic to change public behaviour: social distancing (sōsharu disutansu), self-restraint (jishuku) and the avoidance of the so called “3Cs” (closed spaces, crowds and close-contact situations) were strongly encouraged (though not legally enforced) and masks became an essential accessory throughout the pandemic years (and still are, as at July 2022).

Figure 1: Avoid the “Three Cs”! (graphics by Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; accessed 20 May 2022)

These behavioural changes as well as the varying regulations of the SOEs had significant impacts on individuals’ everyday lives, including love, marriage and family life. Married couples, most of whom have children and more than 60% of whom live in double income households (Ueno 2020, 56), were put under stress due to the closure of elementary, junior high and senior high schools from 2 March 2020 onwards (partially reopening from May onwards) and an increase in teleworking. This was in part understood as a chance to spend more time as a family and to improve familial communication (in particular by men; Ochiai & Suzuki 2020, 9), but it soon became obvious that (young) mothers, in particular, suffered from the demands of having to balance their own work responsibilities (many not being eligible for teleworking or threatened with dismissal), home-schooling the children, and providing three meals a day. While many men also stayed at home, their involvement in inner familial care work did not increase as in the case of women (Ochiai & Suzuki 2020, 5–7). Rather, women had to take care of their husbands as well, trying to create an atmosphere in which husbands could work without disruption, often in extremely confined living spaces (Ochiai & Suzuki 2020). The number of reported cases of domestic violence rose dramatically (Ando 2020) and divorce, a phenomenon widely known as ‘corona divorce’ (korona rikon) rates, increased (Iijima 2021; Ueno 2020).8

At the same time, individuals in search of a love or marriage partner were put under strain: physical distancing regulations and the cancellation of in-person events made the search for a partner difficult, to say the least. Matchmaking events were put on hold from late February 2020 onwards, before they were gradually shifted to the virtual sphere: online dating (onrain dēto), a trend that had slowly started to emerge prior to the pandemic (IBJ 2019), increasingly gained importance and the matchmaking industry recorded a turnover gain (IBJ 2021). Finally, romantic couples—less than 2% of whom cohabit (IPSS 2017, 25; 18–34 years)—had to significantly alter their practices of intimacy, in particular during the first SoE: meetings in person decreased and common dating practices such as going to restaurants or cafés, visiting love hotels, travelling or shopping became rare or even impracticable (Kottmann & Dales forthcoming).

Figure 2: Poster in a Subway Station, Tokyo (photograph by Nora Kottmann)

TV Production Under Pandemic Conditions

In 2020, the pandemic presented TV and film production worldwide with truly unimagined difficulties. A major shock for the Japanese industry was the death of popular comedian Shimura Ken on 29 March 2020; the first celebrity to fall victim to COVID-19 in Japan. At the time, Shimura was acting in the NHK morning drama (asadora) Ēru (“Yell”) in a supporting role. Although some studios continued filming under precarious conditions at the outset of the pandemic (Schilling 2020), by the beginning of the first SoE in early April 2020, many anime and live action TV series had stopped production, causing a considerable break in broadcasting. Among them were, for example, the long-awaited Hanzawa Naoki sequel and Sazae-san, the world’s longest-running cartoon series (1969–) (The Guardian 2020). The asadora series, a long-running fixture of Japanese television that is broadcast on a daily basis, had to be interrupted for the first time in its almost 60-year history.9

With the end of the state of emergency on 25 May 2020, broadcasting corporations began to restart drama production and developed various measures to be able to continue filming as safely as possible. The ‘3Cs’ were a key factor in developing these new procedures, but there were also many other details that specifically affected filming. For example, the public broadcaster NHK published a manual for dorama production at the end of May 2020, which specified daily temperature monitoring for cast and crew and social distancing rules. It also stated that costumes had to be washed after each use. Thanks to these measures, filming for the morning drama could finally resume in June, but the production time increased considerably as a result (The Sankei News 2021). This ‘manualisation’ of drama production became a widespread phenomenon. Fuji TV producer Inaba Naoto reported in an interview that he himself wrote the 20-page manual for the filming of the drama Rupan no Musume (“Daughter of Lupin”, October–December 2020), regulating all hygiene measures in detail (Hara and Takagi 2020).

Another strategy to increase safety for the actors was to rewrite the scripts in order to minimise physical contact between the actors, which led to numerous dilemmas, especially in the case of dramaturgically important fight and kiss scenes (Miyata et al. 2020; TV Tokyo Plus 2020). The number of on-screen characters was reduced in many productions, and film crews were also limited to the most essential people. Furthermore, production teams had to rethink their choice of locations; roof-top terraces became more popular due to the low risk of infection (Location Japan 2020), and the proportion of outdoor scenes overall increased significantly. These developments demonstrate that production conditions inevitably had a strong impact on the content of the series, even where the pandemic was not part of the plot. Insights into the production under pandemic conditions are evident, for example, in the end credits of the drama Uchi no Musume wa, Kareshi ga Dekinai!! (“Date my Daughter!”, January–March 2021, NTV), which include outtakes and footage of the film crew with masks and face shields.

Some series productions chose to actively work with the situation and transfer the setting of the plot to the pandemic. When a series is set in the COVID-19 era, this has the great advantage that hygiene measures do not interfere but, on the contrary, are part of the authentic portrayal. According to the logic of the plot, the characters must adhere to physical distancing rules or wear masks, which means the actors are automatically protected during filming. Two of the series we examine here have chosen this route to place the storyline (completely or partially) in the pandemic: Rimorabu – Futsū no Koi wa Jadō (here abbreviated as Rimorabu) and Nigeru wa Haji da ga Yaku ni Tatsu: Ganbare Jinrui! Shinshun Supesharu!! (here abbreviated as Nigehaji Special). Other ren’ai dorama that aired around the same period also have the pandemic appear in the background of the plot, but do so very discreetly and without the situation being crucial to the development of the story. These include Neechan no Koibito (hereafter, Anekoi) and Koisuru Hahatachi (hereafter, Koihaha). Similar productions (and similar considerations regarding the depiction of the pandemic) could be observed around the world in 2020 (Karimi 2021): as early as August that year, the U.S. channel Freeform aired the mini-series Love in the Time of Corona, while the series Social Distance landed on Netflix in October 2020 (Huver 2021). At the same time, popular long-running shows like Grey’s Anatomy (season 17, November 2020–June 2021) also took up the issue.

A Virtual Love Story: Rimorabu

While there had already been smaller, experimental pandemic-themed productions in early 2020,10 Rimorabu was Japan’s first ‘primetime drama’ set in the Covid era. Its plot takes place between April and December 2020 and revolves around 28-year-old Ōzakura Mimi, who works as a company doctor. She takes her task of propagating and implementing coronavirus hygiene measures in the company very seriously, making herself extremely unpopular, at least in the beginning. In her private life, Mimi-sensei, as she is called, has been single for five years and lives alone. During Japan’s state of emergency, she falls in love with an anonymous chat partner—referred to as ‘Lemon’, his chat name—she accidently meets while playing an online game. Filming for Rimorabu began on 11 September 2020 (remolove_ntv 2020). Producer Hazeyama Hiroko has explained that practical considerations played an important role in the decision to set the story during the pandemic. According to her, Rimorabu was the result of the production team’s search for a concept that would allow them to continue shooting even within the context of rising infections (Supōtsu Hōchi 2021). Rimorabu’s producers faced the problem of having to depict ‘the present’ at a time when ‘the present’ was not constant. This also entailed a certain responsibility: the behaviour of characters in the series could be taken as a model for the viewer’s own handling of the pandemic. At the same time, the production team faced the dilemma that some viewers may not want to be reminded of their difficult everyday lives, but rather seek a distraction. Rimorabu can thus be characterised as a compromise.

The reality of pandemic life, sometimes hard to bear, is presented in a toned-down version, which is achieved through comedic elements and omissions. The darker sides of the pandemic remain a big void in the series: not a single person in the company Mimi-sensei works for becomes infected or has to be quarantined, there are, of course, no deaths and infected people are only referred to once as an abstract number on TV. The various precautions in the series, such as social distancing or disinfecting, thus sometimes seem like rituals detached from their actual meaning, carried out by the characters in constant repetition. For example, when Mimi-sensei is demonstrating the correct removal of a mask, this performance resembles a martial arts technique, and her instructions about social distancing are accompanied by exaggerated facial expressions and gestures. This parody allowed viewers to look at their exhausting everyday life from a comical distance. It is therefore hardly surprising that there were many posts on Twitter attesting to the series’ iyashi (comforting) effect. However, the parody also implicitly portrays the protagonist’s caution as exaggerated. Moreover, as Darlington (2013, 33) describes, such over-the-top portrayals of working women are often an element in dramas that infuse the female protagonist’s success with a “strong dose of ridicule”.

While COVID-19 remains distant as a disease in Rimorabu, other, more mundane problems related to the pandemic are addressed. Employees complain about insufficient space in their home offices and a child accidently shows up in a video conference. Beneath the comedy, people are struggling to come to terms with the pandemic and the measures being taken, especially with regard to their love lives. Rimorabu specifically addresses the question of how love relationships can be initiated and conducted under pandemic conditions. Here, the series focuses on two main topics: first, the online-offline dilemma (‘real’ love versus ‘remote’ love) and second, the problem of creating emotional and physical proximity in times of social distancing.

The love story between Mimi-sensei and her chat partner ‘Lemon’ develops very easily online. We can see both protagonists enjoying chatting, laughing out loud and tensely waiting for a reply. The relationship gets complicated as soon as Mimi-sensei finds out that Lemon is one of her co-workers (while not initially knowing which one), and she starts transferring the love story to the offline world. Her hesitation and inability to express herself in face-to-face interactions stands in clear contrast to her online behaviour, a topic that is addressed repeatedly throughout the series. When Mimi-sensei and Lemon (her co-worker Aobayashi) get closer, they have a hard time transferring their lively online conversations to a face-to-face situation. This is clearly shown, for example, in the scene when Mimi-sensei confesses to Aobayashi that she is his online chat partner, Kusamochi (episode 6). Even though they are sitting next to each other, they resort to using their smartphones to converse with each other (see Figure 3). The text they are writing is visualised in the upper part of the screen (a stylistic device that is often used in the series), which allows the audience to read along. These difficulties in transforming the online romance into a real life relationship are problematised repeatedly over the following episodes. Yet, the series generally portrays ‘real life’ relationships as better and more meaningful. For example, one older co-worker lectures in great detail about the dangers of virtual love relationships (episode 3), and Mimi-sensei and Aobayashi explicitly refer to their relationship as “not normal” (episode 10).

Figure 3: Confession by text message: “[Kusamochi, are you] Ōzakura … Mimi-sensei?”. “Yes!” (c) NTV 2020

While face-to-face communication and ‘being on the same page’ are depicted as important features of a healthy relationship, physical intimacy is only touched upon and presented as something difficult to achieve. In all ten episodes, we get to see only one kiss (episode 3); this kiss is not part of the central love story and, most importantly, is performed with masks, a circumstance that is described as particularly “sexy (eroi)” by a casual observer. Every other attempt to get physically close is somehow disrupted or stopped by the protagonists themselves: again and again, when one of them tries to get closer, the other is shown as becoming nervous or hesitant. For example, we often see Mimi-sensei put on her mask or hold up her hand to prevent other characters from coming too close to her. It remains unclear whether she is truly concerned about a possible infection or whether she uses these measures as an excuse for her unease with physical intimacy in general. Instead of the classic kiss at the conclusion of the series, the last episode ends with the on-screen text: “And then they kissed”. This might be due to the production rules under pandemic conditions or an attempt to express love in an acceptable, ‘socially distant’ way.

Overall, the series suggests that, despite the difficulties, establishing a happy relationship in the sense of a romantic, heterosexual relationship is the ideal course, a topic that gains central importance in the later episodes. Alternative relationships or ‘happy singles’, who consciously decide against romantic relationships and/or focus on other personal relationships are an obvious omission. In this sense, the series seamlessly follows on from earlier productions and the story appears to be trite (despite the twist of making the pandemic central to the plot) and conservative on various levels including the understanding of a ‘normal’ love life for adults and ‘normal’ gender roles. In this sense, the series does not offer any solutions for ‘unnormal’ relationships—despite the subtitle being ‘normal love is the wrong course’.

The Struggles of Young Parents During Pandemic Times and a Real-Life Marriage: Nigehaji Special

In October 2020, filming commenced on a two-and-a-half-hour special episode that continues the story of the hit 2016 drama Nigeru wa Haji da ga Yaku ni Tatsu (hereafter, Nigehaji) (Real Sound 2020). Nigehaji was a socially-conscious romantic comedy centred on Moriyama Mikuri and Tsuzaki Hiramasa, who grow closer through a ‘contract marriage’. The original series, based on the manga by Umino Tsunami, achieved a rating of 20.8% for its final episode and was described as a “drama of national importance” (Katsuki 2016). Writer Katsuki Takashi (2016) praised the drama for its “new perspective” on traditional social norms regarding marriage and gender roles, noting that the construct of a contract marriage allowed the drama to question the assumption that a woman need not be compensated for domestic labour in a relationship based on love. The series’ depiction of diverse types of love, including LGBTQI+ and age-gap attraction also caught the attention of the public (Kawamura 2021a).

Similarly, the Nigehaji Special also touched on current social issues, including paternity leave and the debate over the right of couples to choose separate names upon marriage, which caused a stir in the mainstream and social media (Ishida 2021). In the drama, the issue of surnames arises when Mikuri discovers she is pregnant and the couple, who were living happily together as an unmarried couple, decide it would be best to register their marriage for the sake of the child (extramarital birth is rare in Japan and remains stigmatised). As mandated by the Japanese Civil Code Article 750, the couple are required to choose either the husband’s or the wife’s surname, a situation that puts Japan in a unique category among developed nations as the only one that continues to require single surnames for married couples (Taniguchi and Kaufman 2020). In Nigehaji Special, a small puppet show interrupting the main storyline explains this legal situation to the audience from a critical point of view. As Mikuri and Hiramasa acknowledge, the practice seems outdated; nevertheless, despite their apparent frustration, they choose to take the husband’s name, as is the case with 96% of couples in Japan (Taniguchi and Kaufman 2020, 206). Mikuri and Hiramasa are reflective of an increasing shift towards support for overturning the ban on separate surnames, especially among younger Japanese, as can be observed in recent surveys (Ito and Sato 2022).

The drama’s depiction of the COVID-19 pandemic was also particularly notable. The episode begins in 2019 and runs on into the first half of 2020: Mikuri becomes pregnant, gives birth to a daughter and the young family is physically separated by the circumstances of the pandemic. The pandemic only becomes an issue around 90 minutes into this special drama, but its impact is shown clearly and without sparing all the ugly details, in contrast to the comedy-oriented Rimorabu. Mikuri becomes anxious about the risk of infection to her infant daughter and is fastidious in her approach to hygiene and disinfection. The pandemic also forces Hiramasa to abandon his plans to take paternity leave. Although none of the characters are directly affected by the virus, the drama shows the escalating panic caused by the pandemic and makes references to the rising number of infections and deaths, including that of Shimura Ken (see above), which was reported widely in Japan and elsewhere. The drama even acknowledges the discrimination faced by Asian people in relation to COVID-19 in countries outside of the region.

The final 30 minutes of the special episode focus on the impact of the pandemic on the main characters, in particular, the emotional toll on Mikuri and Hiramasa. Now living apart, they are forced to rely on smartphones and other devices to communicate, which provides solace but also causes misunderstandings, highlighting the fact that digital interactions are not a perfect substitute for physical proximity. The emotional climax comes during a scene in which Mikuri and Hiramasa finally see each other again in Mikuri’s hometown by the sea, but the physical distance between them is so great that they can only wave at each other from afar and talk on their smartphones. The camera alternately captures the two in close-up (shot/reverse-shot technique), showing the emotional closeness between them, but at the end of the conversation, a long shot reveals the great physical distance between them: Mikuri is just a small red spot in the background (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Meeting at a distance: Mikuri and Hiramasa talk on their smartphones while seeing each other from afar after a longer period of separation. (c) TBS 2021

The drama’s depiction of the feelings of anxiety and loneliness caused by the pandemic struck a chord with viewers, but the ultimately heart-warming story also offered the life-affirming message that “someday, we’ll definitely meet again” (Kawamura 2021b). The TV film, which aired during the New Year’s holidays, achieved a relatively high audience rating of 15.5% and trended on social media platforms (Oricon News 2021).

Interestingly, the main actors of Nigehaji, Aragaki Yui and Hoshino Gen, announced in May 2021 that they were getting married. This led to speculation over whether the special circumstances during filming, with much less “outside noise” than usual, might have created good conditions for this real-life love story to unfold (Nishijima 2021).

A Comforting Fairy-Tale in a Time of Crisis: Anekoi

Trailer for Anekoi. (c) Fuji TV YouTube 2020

During the first year of the pandemic, as the Japanese public were coming to grips with their new, restrained way of life, some viewers found the sight of drama characters on television wearing masks and following hygiene protocols reassuring, while others felt that the world of entertainment should offer an escape from their everyday reality (Nakano 2021). One series that attempted to offer the latter, without completely ignoring the pandemic itself, was Neechan no Koibito (“Our Sister’s Soulmate”), also known as Anekoi. While it acknowledged the suffering of Japanese people, the drama’s overwhelming message was “ganbarō” (let’s keep going) and “daijōbu da” (it will be okay), wrapped within a heart-warming yet utterly conventional love story.

Set (and broadcast) during the autumn/winter of 2020—the period between Halloween and New Year’s Day—Anekoi centres on 27-year-old Momoko, a worker in a store selling home interior goods, and her fellow employee and love interest, 31-year-old Manato. Both are affected by tragic histories, which pose obstacles to their relationship, but are able to overcome these with the support of their family and friends. The drama makes direct as well as indirect references to the pandemic. For example, in the first episode, Momoko finds a broken toy globe that acts as a metaphor for the pain and suffering experienced around the world. This idea becomes a recurring motif of the drama. Furthermore, several characters make references to the early days of the pandemic, when the situation was uncertain and people feared for their jobs. There is a flashback scene in which the store is overrun by customers panic buying masks and one of the supporting characters, Miyuki, loses her job in a travel agency due to a downturn in business as a result of travel restrictions.

However, these are minor distractions to the central message, which seems to insist that the worst is over and it is now time to look forward with optimism. Within the world of the drama, people are no longer wearing masks and, unlike the couple in Rimorabu, Momoko and Manato are even able to share a kiss. Furthermore, all the main characters achieve a happy ending, including Miyuki, who is able to secure another job. The key factor to finding happiness, the drama suggests, is to make a personal connection. In other words, as the English title of the series alludes, to find one’s soulmate. In fact, the series offers not one but three parallel love stories, including a romance between Momoko’s supervisor Hinako and Satoshi, who poses as an ordinary co-worker but is in fact the incoming president of the company. The subplot featuring Hinako and Satoshi offers many light-hearted, comical moments in the drama, as well as a fairy-tale ending that involves Satoshi arriving at the store in a formal suit, carrying a bunch of roses, and proposing to Hinako on one knee.

The importance of close family bonds is another major theme of Anekoi. Gaining the acceptance of their loved ones plays a crucial role in the development of the relationship between the two central protagonists, and there are several uplifting scenes of Momoko, her younger brothers and close friends and family laughing and generally enjoying themselves as they sit around the family dining table. The dining table, as a site for giving and receiving nourishment, has particular symbolic relevance as a cultural representation of familial harmony (Mithani 2019, 77). In Anekoi, it serves as an important space for confession and communal bonding―a place for each character to express their fears, hopes and desires and receive support, acknowledgement and acceptance from others. This positive benefit of social interaction is reflected in research on the effects of the pandemic on family relationships, which suggests that the opportunity to spend more time together, including shared meals, increased communication and, for some, improved the atmosphere within the home (Kim and Zulueta 2020, 365). However, in other cases, increased time spent together in a confined space only exacerbated tension and stress (Kim and Zulueta 2020, 365), an aspect that Anekoi largely avoids.

The final scene of the series is accompanied by a voiceover provided by Momoko’s brother, Kazuki, that emphasises the message of optimism: “This planet we live on certainly maybe wounded and weakened right now, but if all of us living in the present have an unrequited love for happiness, we will be okay, this planet won’t break.” The drama was appealing to those who felt comforted by its portrayal of an idealistic world, devoid of “bad people” and its romanticised depiction of family and love, which was enough to make viewers feel “warm and fluffy” inside (Sakaguchi 2021). Journalists praised Anekoi for its “unshowy” yet “heart-wrenching” love story (Asahi Shimbun 2020), set within the context of people mutually supporting each other as they do their best to survive the “new normal” (Ōno 2020). Furthermore, the drama largely avoided touching on any particularly depressing aspects of the pandemic—there was, for example no mention of deaths caused by the coronavirus. This suggests that, as Gössmann (2022) observes in relation to drama production following the 2011 triple disaster, in times of crisis, those involved in making television drama prefer to focus on providing solace and comfort to their viewers, and are reluctant to address more problematic issues.

Pandemic Anxiety and ‘Corona Divorce’: Koihaha

Trailer for Koihaha. (c) TBS YouTube 2020

The coronavirus pandemic had an enormous impact on people’s everyday lives around the world. Lockdowns and stay-at-home orders forced millions of people to work or study from home, causing couples and families who had previously spent most of their working hours apart suddenly having to share the same space 24 hours a day. In Japan, the increase in the amount of time couples were spending together, as well as the added burden on working mothers of having to care for and educate children while schools were closed, led to worries of an increase in spousal tension and the term ‘corona divorce’ (korona-rikon) began trending in the media.11 Divorce counsellor Okano Atsuko reported that she had seen a 50% increase in telephone consultations since companies initiated remote working policies in March 2020, as couples struggled to cope with the stress of being shut inside the home together all day (Miyahara 2020). There was even a widely-reported attempt by an enterprising property agency to capitalise on the phenomenon by advertising its rental rooms as a ‘temporary refuge’ and divorce prevention measure for people needing time away from home (Kasoku Co., Inc. 2020). The economic consequences of the pandemic, which resulted in job losses for some, may have also caused anxiety and, for example, a loss of pride for men who lost their status as breadwinner and were forced to stay at home, which could lead to the breakdown of a marriage, as one real-life story reported in a lifestyle magazine illustrates (Fujino 2022).

The effect of the pandemic on the conjugal relationship was explored briefly in the drama series Koisuru Hahatachi (“Mothers in Love”, hereafter, Koihaha). Based on the manga of the same name by Saimon Fumi, the drama spans several years, with only the final two episodes being set during the coronavirus pandemic and its aftermath. The drama focuses on the love lives of three mothers in their 30s and 40s, including divorcee An, who has remarried in middle age. Having already experienced the trauma of miscarriage, An’s husband Saiki becomes even more anxious when he is forced to work from home due to the pandemic. Afraid of losing his wife too, Saiki refuses to allow her out of the house even after the stay-at-home order is lifted, prompting her to escape to the seaside with a friend to relieve her own stress. Eventually, Saiki admits that he has been anxious about his professional future and was somewhat irritated by the strength An had shown in recovering from their shared trauma, while he was continuing to suffer. Saiki’s sentiments perhaps reflect the loss of pride experienced by men who felt unable to protect their families from the virus.

The couple eventually divorce, but instead of going their separate ways, they are able to form a new relationship as working partners, which An describes as a way for them to “live together, side-by-side” (episode 9). This echoes the suggestion by divorce counsellor Okano that the pandemic could change the nature of marriage, leading to new lifestyles and new perspectives on relationships, such as living separate lives under the same roof (kateinai bekkyo), but in a positive sense (Miyahara 2020). Indeed, Koihaha, which touches on provocative topics, such as the sexual desire of mothers and extramarital affairs, offers an alternative narrative to the pro-nuptial discourse found in other romantic dramas. All three central protagonists experience troubled marriages, infidelity and divorce, and by the end of the series, only one of the women achieves happiness in a matrimonial relationship. The other women are able to find fulfilment and companionship outside of the institution of marriage.

One of these is career woman and mother Yūko, portrayed by 46-year-old Yoshida Yō, who falls in love with her subordinate Akasaka, portrayed by 28-year-old Isomura Hayato. At the conclusion of the drama, the couple decide to forgo marriage in favour of co-habiting—as mentioned earlier, still a rarity in Japan—and their storyline featured a number of bedroom scenes. At a time when many wives and mothers were feeling the strain of the pandemic on their relationships, the extramarital affair between an older woman and a handsome younger man may have provided a welcome distraction. The many adoring fan messages posted on the drama’s official webpage suggest that the couple’s love-story was extremely popular with viewers (TBS 2020).

Romantic dramas featuring older women and younger men are not a new phenomenon for Japanese television, although opinions differ as to whether the depictions of these types of relationships are a progressive development or reinforce conservative gender stereotypes (see Gössmann 2016 and Darlington 2013, respectively). Nevertheless, for an industry that places an excessive emphasis on youth, casting women over 45 as romantic leads is a growing trend that challenges existing perceptions of older women, in particular mothers, as undesirable or asexual (Mithani 2020). From the perspective of the broadcaster, it also reflects the need to appeal to an ageing female audience. Furthermore, the romantic pairing of an older woman and younger man might be particularly beneficial for broadcasters as it has the potential to draw viewers from a wide age-range, from the teenaged fans of the handsome young male actors to the middle-aged working women and housewives who find it easier to identify with a heroine at a similar stage of life.

Comments posted to the official website for Koihaha reveal that viewers, who were overwhelmingly women aged between 30 to 60, were able to empathise with the three mothers at the centre of the drama, whose stories reflected their own hidden hopes and desires (TBS 2020). This phenomenon is not uncommon during times of crisis: having been made keenly aware of their own mortality by the coronavirus, some people were re-evaluating their lives or rediscovering urges that had long been smouldering within themselves (Miyahara 2020; Okano 2020). Viewers also commented that they felt encouraged by the drama’s positive message, including its depiction of a post-pandemic Japan (TBS 2020). At a time when Japanese wives and mothers, like their counterparts around the world, were adjusting to a new reality in the home, Koihaha offered a form of romantic escapism that allowed them to look beyond the dark days of the pandemic to a more optimistic future.

Discussion: Navigating Uncertainties and Balancing Different Audiences

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has not only had a significant impact on people’s relational and familial practices across the globe, it has also affected media productions in various, intertwined ways. The case of Japanese romantic TV series exemplifies the need of production companies to adapt to pandemic conditions, both with regard to the actual production process—as seen in precautionary measures during shoots—and most importantly, with regard to storylines, topics and, consequently, adaptions of the script. Producers, confronted with declining viewing figures for two decades now, have been and continue to be torn between different audiences and their manifold, possibly divergent expectations regarding the depictions of love, dating and (marital) relationships and depictions of the pandemic and its attendant regulations, while the latter keep on enfolding and developing in real life. Most of the dramas we have discussed here appear to be designed to soothe or offer escapism during a time of anxiety and uncertainty, to varying extents, through romantic encounters, happy endings or comforting fairy tales, with the pandemic, in particular its dark side, largely absent. This might, at the same time, be a matter of practical considerations, as Asai Mayumi, author of Sorokatsu joshi no susume (“Recommendations for Single Women’s Activities”, 2019) which was the premise for the TV series of the same name in early 2022, deliberates:

Well, I think it’s like that, isn’t it: […] if you address the pandemic too much, all the actors would basically have to wear masks the whole time. But, if you’ve gone to the trouble of having beautiful actresses, for them to then wear masks. How can I put it? It would not be ideal from a dramaturgic or visual perspective (Interview Nora Kottmann; November 2020).

As scholars have previously noted, the stars cast in a TV series play a central role in its success and serve an important function as a point of engagement for the audience (Lukács 2010; Tsai 2010). Furthermore, Kirsch (2014, 83) has highlighted the role of close-ups of facial expressions in creating a sense of proximity between tarento (television celebrities) and viewers. In fictional drama, they draw viewers into the action by providing insight into the thoughts and feelings of the characters (Mithani 2019, 75). In light of this, it is not surprising that drama producers were perhaps reluctant to see their stars’ faces covered up.12

In general, the series we have examined here address several topical issues regarding individuals’ relationship worlds and practices, a common or classical approach of love or lifestyle series since the 1980s. This includes, but is not limited to, topics such as online dating, sexual encounters, extramarital affairs, paternity leave, gender equality and marital life, communication in marital relationships, as well as divorce. The depictions follow the common pattern of the genre during the last ten to twenty years: while they might seem progressive or innovative (and do sometimes offer unconventional messages, as can be seen in Koihaha), most of these series ultimately remain entrenched in traditional, conservative patterns, stressing the importance and merits of heterosexual marriage over other relationship forms. Nevertheless, the ongoing pandemic adds an additional layer. In the case of the so-called pandemic drama, the reflexive function of TV series (see introduction) seems to be particularly relevant: we not only accompany the main characters through the ups and downs of their love relationships and in their search for their desired way of living. The series also reflect upon what ‘correct’ behaviour looks like in times of the pandemic, how the ‘new normal’ is defined and shaped, and, above all, how social and physical proximity can be renegotiated and redefined for individuals and families in times of social distancing, of ‘staying at home’, of uncertainty and social isolation.

Overall, and despite the depiction of unconventional or progressive relationships (as can be seen in Koihaha), we cannot identify any significant or ground-breaking changes in the selected dramas compared to earlier productions of the ren’ai format; neither with regard to love, dating and (marital) relationships, nor with regard to overall story lines. Rather, the select series tie in with various, seemingly contradicting trends that were present already prior to the pandemic and that range from conservative Cinderella stories to more unusual constellations (age-gap relationships, LGBTQI+, etc.). Since the four dramas were all planned before the pandemic, this continuity in both conservative as well as progressive and unconventional content does not seem surprising. And while our findings provide a timely snapshot of drama trends early on in the pandemic, additional work is needed to explore longer-term evolutions in the format.

In half of our examples—and this seems to align with public discourse and statistical evidence on the topic—we can identify a tendency towards (even) more conservative, traditional narrations and depictions: Rimorabu and Anekoi propagate (heterosexual) marriage as the ultimate goal in times of uncertainty, social distancing and loneliness in a surprisingly direct way. While Nigehaji is critical of the conventional construct of marriage based on a strict division of labour, it ultimately upholds the institution. Among our examples, only Koihaha challenges the validity of marriage as the ideal relationship structure. While this messaging is nothing new—the devaluation of marriage in television drama has previously been noted (Hu 2010)—the fact that this still seems somewhat unusual reflects the dominance of the pro-marital discourse.

Nevertheless, Nigehaji, Koihaha and (to a lesser extent) Anekoi did touch on a number of pertinent issues, such as the impact of the pandemic on women’s employment, the gendered division of labour, marital tensions and anxiety. In particular, the situation depicted in Nigehaji, where the husband has to give up his parental leave and the wife is forced to take over childcare all by herself, abandoning their aspirations of a gender-equal marriage, resonates with what social scientists, mainly in Western contexts, have often described as a “re-traditionalization” (Brini et al 2021): In autumn 2020 the World Economic Forum (2020) released a video entitled “The Coronovirus might be gender neutral but the pandemic effects are not”, acknowledging the pandemic’s devastating consequences on women around the world. Women not only experienced a greater economic impact; they also disproportionally shouldered the increase in care work associated with school closures and stay at home policies. These developments might “trigger a regression in gender inequalities [on a couple level], pushing women back to more traditional roles” (Brini et al 2021) and reversing achievements towards gender equality made in the last few decades.

A similar discourse has also emerged in Japan, but with a notable difference: feminist sociologists Ochiai Emiko and Suzuki Nanami (2020) as well as Ueno Chizuko (2020) argue that the pandemic has made pre-existing, pervasive gender inequalities (as discussed in the introduction) visible and, at the same time, worsened them. Care, or ‘shadow work’, they argue, has come to light, while at the same time the burden on women has further increased. More worryingly, suicides among women (in particular those under forty), thought to be exacerbated by job losses and an increase in incidents of domestic violence, have risen substantially since the beginning of the crisis (Iijima 2020; Ueda, Nordström & Matsubayashi 2021). In the dramas we have examined, however, any disruptions were ultimately smoothed over, and the more serious consequences of the pandemic on women remained unexplored.

Finally, all the series discussed in this article can be characterised by a focus on (heterosexual) couple relationships. While the series also depict several seemingly progressive relationship forms (most likely to appeal to an ever-diversifying audience) and elaborate on ‘new’ or changing ways to initiate and maintain relationships (e.g., online dating and communication), they ultimately do not suggest any truly innovative ways of living and belonging beyond the heterosexual couple norm—at least with regard to the main characters and the main story lines. In an age in which diversity (tayōsei) has become a buzzword in calls for reforming legal, political and societal institutions in the context of demographic change and an increasing precarization of employment, the true acknowledgement of multiple relationships and lifestyles beyond the heterosexual marriage and family, such as the increasing numbers of unmarried couples, singles and people who identify as LGBTQI+, both ‘on screen’ and in reality, is one of the major issues of the present and the future. We see the potential for future work to take off in interesting directions from here.

References

Ando, Rei. 2020. “Domestic Violence and Japan’s COVID-19 Pandemic.” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Japan Focus 18 (18, 7): 1–11.

Asahi Shimbun. 2020. “Jikkuri tannō, aki dorama: Jitsuryokuha no gensaku kyakuhon, ‘renai’ hōsaku kishazadankai [Thoroughly proficient autumn dramas: Strong source materials/screenplays, bumper crop of ‘romances’ – reporter round-table discussion].” Asahi Shimbun, 14 November 2020, p. 2.

Asai, M. 2019. Soro katsu joshi no susume [Recommendations for Single Women’s Activities]. Tokyo: Tankonon.

Brini, E., M. Lenko, S. Scherer, and A. Vitali. 2021. “Retraditionalisation? Work Patterns of Families with Children During the Pandemic in Italy.” Demographic Research 45(31): 957–972.

Dalton, E., and L. Dales. 2016. “Online Konkatsu and the Gendered Ideals of Marriage in Contemporary Japan.” Japanese Studies 36(1): 1–19.

Darlington, T. 2013. “Josei Drama and Japanese Television’s ‘New Woman’.” Journal of Popular Television 1(1): 25–37.

Fujino, A. 2022.“Korona to watashi: Otto no「gomen」ni kakusareta higaisha ishiki … taitō fūfu ga korona rikon ni itatta riyū to wa ~ sono 2 ~” [Corona and me: The victim mentality hiding in my husband’s ‘sorry’ … the reason a couple with an equal relationship ended up divorcing – part 2].” Serai.jp, 15 January 2022 (accessed 3 March 2022).

Gössmann, H. 2000. “New Role Models for Men and Women? Gender in Japanese TV Dramas.” In Japan Pop! Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture, edited by T. J. Craig, 207–221. New York: M. S. Sharpe.

Gössmann, H. 2016. “Kontinuität und Wandel weiblicher und männlicher Lebensentwürfe in japanischen Fernsehserien (terebi dorama) seit der Jahrtausendwende.” In Japanische Populärkultur und Gender. Ein Studienbuch, edited by M. Mae, E. Scherer, and K. Hülsmann, 127–148. Heidelberg: Springer.

Gössmann, H. 2022. “Solace or Criticism? The Representation of the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster in Television Dramas and Films.” In Handbook of Japanese Media and Popular Culture in Transition, edited by F. Mithani and G. Kirsch, 32-44. Tokyo: MHM Limited.

Goldstein-Gidoni, O. 2019. “The Japanese Corporate Family: The Marital Gender Contract Facing New Challenges.” Journal of Family Issues 40(7): 835–864.

Guardian, The. 2020. “Sazae-san, the World’s Longest-running Cartoon, Put on Hold by Coronavirus.” The Guardian, 12 May 2020 (accessed 2 May 2022).

Hara, R. and S. Takagi. 2020. “Rabushīn ari, akushon ari … nōkōsesshoku to tonariawase no dorama satsuei de no korona taisaku” [There are love scenes, there is action … corona measures during drama production with ‘close contact’].” Fuji News Network, 11 November 2020 (accessed 2 May 2022).

Hu, K. 2010. “Can‘t Live Without Happiness: Reflexivity and Japanese TV Drama”. In Television, Japan, and Globalization, edited by M. Yoshimoto, E. Tsai, and J. Choi, 195–216. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Huver, S. 2021. “‘Love in the Time of Corona’, ‘Coastal Elites’ and ‘Social Distance’ Tackled Pandemic on Small Screen in Real Time.” The Hollywood Reporter, 12 June 2021 (accessed 2 May 2022).

IBJ. 2019. “Dokushin danjo no ‘imadoki no konkatsu johō’ [The status quo of singles’ marriage hunting activities].” IBJ webpage (accessed 2 May 2022).

IBJ. 2021. “Korona-mae to hikaku shite ‘fukugyō’ de kekkon sōdanjo wo stāto suru kata ga 14% zōka! [14% increase in individuals who start marriage hunting in comparison to pre pandemic times!].” IBJ webpage (accessed 2 May 2022).

Iijima, Y. 2021. Rupo. Koronaka de oitsumerareru joseitachi. Fukamaru kodoku to hinkon [Report: Women cornered by the Corona pandemic – increasing loneliness and poverty]. Tokyo: Kōbunshashinsho.

Ishida, H. 2021. “(Media kūkankō) Netto yoron kashōhyōka dekinu, 「Nigehaji」hannō [(Media space report) We can’t underestimate the social media]”, Asahi Shimbun 24 April 2021, p. 13.

Ito, N. and Sato, K. 2022. “Majority of under 40s in Japan support selective surnames for married couples: survey.” Mainichi Daily News [online] 24 February 2022.

IPSS (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research). 2017. “Gendai nihon no kekkon to shussan. Dai-15-kai shusshō dōkō kihon chōsa hōkokusho (Marriage and Childbirth in Japan Today: The Fifteenth Japanese National Fertility Survey).” In Survey Series 35 (accessed 2 May 2022).

Iwata-Weickgenannt, K. 2013. “Terebidorama ni miru raifukōsu no datsuhyōjunka to mikonka no hyōshō. ‘Araundo 40’ to ‘Konkatsu! ’ wo rei ni (De-standardization of Life-Courses and Representations of Singlehood in the Japanese TV Dramas Around 40 and Konkatsu).” In Raifukōsu sentaku no yukue. Nihon to doitsu no shigoto, kazoku, sumai (Beyond a Standardized Life Course. Biographical Choices about Work, Family and Housing in Japan and Germany), edited by H. Tanaka, M. Godzik, and Ch. Iwata-Weickgenannt, 184–208. Tokyo: Shinyōsha.

Karimi, F. 2021. “Some TV Shows are Telling Stories About the Pandemic. Some Viewers Wish They Wouldn’t.” CNN Business, 21 February 2021 (accessed 2 May 2022).

Kasoku Co., Inc. 2020. Korona rikon bōshi no madoguchi [Corona divorce prevention counter]. Online (accessed 3 March 2022).

Katsuki, T. 2016. “Naze ‘Nigehaji’ wa ‘kokuminteki dorama’ ni nari eta no ka? [Why has ‘Nigehaji’ become a ‘national drama’?].” AERAdot (accessed: 24 February 2022).

Kawamura, T. 2021a. “Minna de koete yuke: TBS kakari ‘Nigeru wa haji da ga yaku ni tatsu SP’ Hoshino Gen Aragaki Yui shinnen tokushū dai 2 bu, terebi rajio [Let’s overcome it together: Hoshino Gen and Aragaki Yui in ‘The Full-time Wife Escapist SPECIAL’ (TBS) new year special report part 2, TV & radio].” Asahi Shimbun, 1 January, p. 1.

Kawamura, T. 2021b. “Shussan ikuji ni funtō suru futari ‘Nigeru wa haji da ga yaku ni tatsu SP’ shinnen tokushū dai 2 bu, terebi rajio [A couple’s tough struggle through childbirth and childrearing: ‘The Full-time Wife Escapist SPECIAL’ new year special report part 2, TV & radio].” Asahi Shimbun, 1 January, p. 5.

Kim, A. J. and J. O. Zulueta 2020. “Japanese Families and COVID-19: ‘Self-Restraint’, Confined Living Spaces, and Enhanced Interactions.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 51 (3/4): 360-368. DOI: 10.3138/jcfs.51.3-4.011

Kirsch, G. 2014. “Next-door divas: Japanese tarento, television and consumption.” Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema, 6:1, 74-88. DOI: 10.1080/17564905.2014.929411

Kumiko, E. 2018. “Singlehood in ‘Precarious Japan’: Examining New Gender Tropes and Inter-gender Communication in a Culture of Uncertainty.” Japan Forum 31(2): 165–185.

Kottmann, N. 2020. “Games of Romance? Tokyo in Search of Love and Unity in Diversity.” In Japan through the lens of the Tokyo Olympics, edited by B. Holthus, I. Gangé, W. Manzenreiter, and F. Waldenberger, 89–94. London: Routledge.

Kottmann, N. and L. Dales (forthcoming). “Doing Intimacy in Pandemic Times: Findings of a Large-scale Survey Among Singles in Japan.” Social Science Japan Journal.

Location Japan. 2020. “‘Koi ata’ mo ‘Rimorabu’ mo ano basho de satsuei! Koronaka de ninki kyūjōshō no roke” [Both ‘Koi Ata’ and ‘Remolove’ were filmed at that location! This location is rapidly gaining popularity due to the COVID-19 pandemic].” Location Japan, 25 December 2020 (accessed 2 May 2022).

Lukács, G. 2010. Scripted Affects, Branded Selves: Television, Subjectivity, and Capitalism in 1990s Japan. (1 ed.). Durham: Duke University Press.

Mainabi Nyūsu. 2020. “‘#Rimorabu’ Haru no oshare masuku ha ‘koseiteki na gara wo erabimashita’ [We designed #Rimorabu Haru’s fancy mask in order to convey individuality].” Mainabi Nyūsu, 20 December 2020 (accessed 13 May 2022).

Mithani, F. 2019. “(De)Constructing Nostalgic Myths of the Mother in Japanese drama Woman.” Series – International Journal of TV Serial Narratives 5(2): 71–82.

Mithani, F. 2020. “Maternal Fantasies in an Era of Crisis – Single Mothers, Self-Sacrifice

and Sexuality in Japanese Television Drama.” In Motherhood in Contemporary International Perspective: Continuity and Change, edited by F. Portier-Le Cocq, 177–190. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Miyahara, H. 2020. “Korona de rikon sōdan ga 5 warimashi! 20~30 dai ga「jukunen rikon no maedaoshi」ni hashiru riyū” [Divorce consultations up 50% during corona pandemic! The reason people in their 20s and 30s are speeding towards ‘early middle-aged divorce’]. Diamond Online, 17 October 2020 (accessed 3 March 2022).

Miyata, Y., K. Kuroda, and T. Kawamura. 2020. “Japanese TV faces real-life drama of staying on air amid virus”. Asahi Shimbun, 7 April 2020 (accessed 2 May 2022).

Nakano, N. 2021. “Korona-ka o hanei shita dorama gekigen “korona-nare” shita ima, motomerareru dorama no arikata to wa [Sharp drop in dramas reflecting the coronavirus pandemic: what viewers want from dramas now they are ‘used to corona’].” Oricon News, 14 August 2021 (accessed 1 March 2022).

NHK. 2020. “Shinkei korona uirusu kansen o bōshi suru tame no dorama seisaku manyuaru ni tsuite” [About the drama production manual to prevent transmission of the novel coronavirus]. NHK Public Relations Bureau, 27 May 2020 (accessed 2 May 2022 via Internet Archive).

NIID (National Institute for Infectious Diseases). 2020. Field Briefing. Diamond Princess COVID-19 Cases. Online (accessed 2 May 2022).

Nishijima, T. 2021. “‘Mitsu’ o sakeru koto de ‘mitsu’ ni naru? Koronaka de satsuei genba ni henka, kyōensha no dengekikon no kanōsei [Avoiding ‘close contact’ brings you ‘close’? The Corona disaster has changed filming, and this may have caused a whirlwind wedding between co-stars].” Oricon News, 3 June 2021 (accessed 2 May 2022).

Ochiai, E., and N. Suzuki. 2020. “COVID-19 kinkyūjitai sengenka ni okeru zaitakukinmu no jittaichōsa. Kazoku oyobi jendā he no kōka wo chūshin ni [Survey on teleworking during the first COVID-19 State of Emergency. Focusing on the effects on families and gender].” Kyoto Journal of Sociology XXVIII, December 2020, 1-13.

Okano, A. 2020. “‘Sekkusuresu de jinsei o oetakunai’ korona rikon o ketsui shita otto no iiwake ‘majime otto’ no rikon sōdan ga fueteiru” [Rise in divorce consultations for ‘diligent husbands’, who explain: ‘I don’t want to die without having sex again’].” President Online, 13 October 2020 (accessed 4 March 2022).

Ōno, T. 2020. “Shishashitsu: ‘Neechan no koibito’ atarashii nichijō o ikiru hitobito [Preview screening room: ‘Our Sister’s Soulmate’: People living the new normal].” Asahi Shimbun, 27 October 2020, p. 36.

Oricon News. 2021. “Aragaki Yui & Hoshino Gen ‘Nigehaji’ SP 15.5% 4-nen buri shinsaku de mo shiij atsumeru [‘Nigehaji’ Special with Aragaki Yui & Hoshino Gen reaches 15.5%; first new episode in 4 years gaining popularity].” Oricon News, 4 January 2021 (accessed 2 May 2022).

Real Sound. 2020. “‘Nigeru ha Haji da ga Yaku ni Tatsu’ shinshun SP kurankin Aragaki Yui ‘Chotto shita kibōni naretara’ [Filming begins on ‘The Full-Time Wife Escapist’, New Year’s Special Aragaki Yui: ‘To provide some hope’].” Real Sound, 6 October 2020 (accessed 13 May 2022)

remolove_ntv 2020. “Kurankuin (Filming begins).” Instagram, 11 September 2020 (accessed 10 May 2022).

Sakaguchi, S. 2021. “Hagaki tsūshin: 12gatsu no tōkō kara: Ōen shitai [Postcards to the editor: From December’s submissions: I want to support them].” Asahi Shimbun, 8 January 2021, p. 18.

Sankei News, The. 2021. “‘Kokoro ni todoku asadora kitai’ NHK kaichō ‘Okaerimone’ 17nichi sutāto [‘In expectation of a heart-warming morning drama’ NHK president ‘Okareimono’ to start on the 17th’].” The Sankei News 13 May 2021 (accessed 10 May 2022)

Scherer, E. 2016 “Alternative Lebensmodelle von der Stange? Konstruktion und Rezeption von Geschlechteridentität in japanischen Fernsehserien (terebi dorama) [A Ready-Made Alternative Lifestyle? Construction and Reception of Gender Identity in Japanese TV Series].” In Japanische Populärkultur und Gender. Ein Studienbuch [Japanese Popular Culture and Gender. A Handbook], edited by M. Mae, E. Scherer, and K. Hülsmann, 149–175. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Schilling, M. 2020. “Japan’s film and TV industries soldier on despite coronavirus.” Japan Times, 9 April 2020 (accessed 2 May 2022).

Supōtsu Hōchi. 2021. “Haru shuen chijōha hatsu no ‘korona no aru sekaikan wo egaku’ dorama ‘Rimorabu’ 10-14 sutāto … NTV 10gatsu kaihen kaiken [The first drama situated in a pandemic world with Haru as main character. Start October 14 … NTV October News Report].” Supōtsu Hōchi, 10 September 2020 (accessed 13 May 2022).

Tanaka, M. et al. 2018. “(Kōron) SNS ni ikiru watashitachi: Tanaka Mei, Saimon Fumi, Doi Takayoshi [(Cultivated debate) Tanaka Mei, Saimon Fumi and Doi Takayoshi: Our lives on SNS).” Asahi Shimbun 22 December, p. 15.

Taniguchi, H., Kaufman, G. 2020. “Attitudes Toward Married Persons’ Surnames in Twenty-First Century Japan.” Gender Issues 37: 205–222.

TBS. 2020. “Kinyō dorama ‘Koisuru hahatachi’: Fan messēji [Friday drama ‘Mothers in Love’ fan messages.” TBS Terebi online (accessed 4 March 2022).

Togo, K. 2020. “The First Phase of Japan’s Response to COVID-19.” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Japan Focus 18 (14): 1–5.

Tsai, E. 2010. “The Dramatic Consequences of Playing a Lover: Stars and Televisual Culture in Japan.” In Television, Japan, and Globalization, edited by E. Tsai, M. Yoshimoto and J. Choi, 93–116. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan Press.

TV Tokyo Plus 2020. “Sannin no dorama purodyūsā ga kataru with korona; kisushīn wa honban dake? Dorama seisaku gaidorain no jitsujō o akasu [Three drama producers talk about the corona situation; kissing scenes only for the main take? Revealing the reality of drama production]. ” TV Tokyo Plus, 30 May 2020 (accessed 2 May 2022).

Ueno, C. 2020. “Koronaka to jendā” [Corona and Gender]”. In Shingata korona uirusu to watashitachi no shakai [The Novel Coronavirus and our Society], edited by T. Mori, 55–79, Tokyo: Ronzōsha.

Ueda, M., R. Nordström, and T. Matsubayashi. 2021. “Suicide and Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Japan.” Journal of Public Health. Online first.

World Economic Forum. 2020. The Coronavirus might be Gender Neutral but the Pandemic’s Effects are not. 23 October 2020 (accessed 8 May 2022).

Yamada, M., and T. Shirakawa. 2008. ‘Konkatsu’ jidai [The Era of the ‘Marriage Hunting’]. Tokyo: Discover 21.

Notes

Widowed or divorced individuals as well as individuals under the age of fifty who are not (yet) married.

As defined in official Japanese statistics, this refers to individuals who have never been married at the age of fifty.

While in the past these series achieved very high ratings (e.g., Byūtifuru Raifu [“Beautiful Life”], TBS, averaged 32.3% in 2000), today ratings around 10% are normal. The decline in ratings has resulted from major transformations in the field of television, a topic that we will not address here due to the scope of the article.

Rimorabu – Futsū no Koi wa Jadō (“Remote Love – Normal Love is the Wrong Course”), aired October–December 2020, NTV (Wednesday, 22.00).

Nigeru wa Haji da ga Yaku ni Tatsu: Ganbare Jinrui! Shinshun Supesharu!! (“The Full-Time Wife Escapist: Hang in there, Humankind! New Year’s Special!!”), 2 January 2021, TBS (21.00–22.25).

Neechan no Koibito (“Our Sister’s Soulmate”), aired October–December 2020, Fuji TV(Tuesday, 21.00).

The situation of single mothers, in particular, deteriorated due to various factors such as economic hardship, precarious employment, lay-offs, etc. (Iijima 2021).

From June 29 to September 11, NHK simply repeated the first 65 episodes of the asadora Yell before continuing the story.

The television film Sekai wa 3 de Dekiteiru (“The World is Made of Three”, Fuji TV, aired June 11, 2020, 23:00–23:40) was made during the SoE in Japan. The production team used video conferencing to prepare for the shoot and reduced the plot to a minimum. The film gets by with only one actor (Hayashi Kentō), who plays triplets. The NHK two-parter Remote Drama Living (May 30 & June 6, 2020, 23:30–23:45) was made completely remotely by the actors filming themselves. And in a TV film by renowned horror director Nakata Hideo, Rīmoto de Korosareru (“Killed Remotely”, Nippon TV, July 26, 2020, 22:30–23:25), murders among high school students occur in a video conference setting.

At one point in April 2020, #コロナ離婚 [#koronarikon] was the third most popular hashtag among Japan-based twitter users (see Trending Archive).

Conversely, some production companies saw masks as a marketing opportunity and included “fancy masks” (oshare masuku) in their merchandise offerings. This was, at least in the case of Rimorabu, a relatively successful strategy (Mainabi Nyūsu 2020).