Abstract: In Fukushima there are two museums that present different narratives of the 3.11 natural disaster and nuclear crisis. TEPCO’s Decommissioning Archive Center focuses on the nuclear accident, what its workers endured and provides rich details on the decommissioning process expected to take three to four decades. The Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum focuses on how the lives of the prefecture’s residents were affected by the cascading 3.11 disaster. The Archive elides many controversial issues that reflect badly on the utility while the Memorial conveys the human tragedy while addressing some of the controversies not covered in the Archive. TEPCO presents an evasive narrative at the Archive, but it is slickly packaged and casts the utility in the best light possible. The Memorial is impressive in scope and conveys the extent of the various tragedies with updates that responded to patrons’ criticisms about controversial issues.

Museums are important sites for shaping public memory and promoting desired narratives, especially concerning controversial issues and events. The goal is to influence how visitors think about and remember what have become collective memories, and thereby shape public discourse. Thus, much is at stake in how the past is selected and represented at sites that commemorate the divisive past and assert interpretations of it. It’s important to examine museums like texts, read between the lines and see what is marginalized, ignored, emphasized and distorted in the displays. Two distinctive narratives about the Fukushima nuclear disaster feature in two museums in Fukushima Prefecture, the TEPCO Decommissioning Archive and the prefectural government’s Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum. The contrast is stunning if not predictable.

The strategy of the TEPCO facility is to elide awkward details and emphasize how its dedicated workers, at great personal risk, saved the day and how the utility is committed to cleaning up the mess and acting responsibly. It was never going to be easy for TEPCO to burnish its reputation, but with this slick facility and some artful spin the Archive makes the best of the poor hand the utility dealt itself. The prefectural museum focuses on the human element and how the natural and man-made nuclear disasters of 3.11 wreaked havoc on communities and families, endangered the health of evacuees and children, assigning blame for what was and what was not done while also trying to suggest that a brighter future for Fukushima is emerging. The Memorial Museum is more engaging and visceral while TEPCO presents a more dispassionate narrative that works to normalize and routinize the trauma while highlighting progress. Museums are moving targets, as exhibits and panels are updated and revised, owing to public pressure in the case of the Memorial Museum and the evolving process of decommissioning for the TEPCO Archive.

TEPCO Decommissioning Archive Center

Credit: Jeff Kingston

The TEPCO Archive opened in late 2018 in the town of Tomioka, about 10 km south of the stricken reactors. Its stated purpose is to “preserve the memories and records of the nuclear accident at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, and to share the remorse and lessons learned, both within TEPCO and with society as a whole.”(Nippon.com 2020) Up to a point this is correct, but the remorse and lessons learned is overshadowed by the detailed exhibits and explanations about nuclear energy technology and the decommissioning process. The archive’s pamphlet suggests that “TEPCO has a keen sense of its responsibility to record the events and preserve the memory of the nuclear accident”, but this is a selective memory that is more evasive than forthright about the causes and unfolding consequences of the three meltdowns. One exits the museum knowing more about how TEPCO and its workers were affected by the nuclear accident than how it affected the people living in the vicinity.

There is a collage of TEPCO workers specifying the number of people currently employed in Fukushima, 4,170 as of mid-April 2022. This display is there to underscore how important TEPCO remains to local communities, generating jobs in a depressed region. The company has kept faith with its employees while betraying their hometowns. Good jobs are one of the inducements offered when TEPCO began building the nuclear plant in 1967. The government and utilities selected remote, depressed towns for siting reactors, offering lavish subsidies and well-paid jobs that were a lifeline for these communities. (Onitsuka 2012) They also promoted the myth of 100% safety to reassure locals that there was nothing to worry about until they discovered it was a fairy tale with an unhappy ending.

TEPCO’s Fukushima employees

Credit: Jeff Kingston

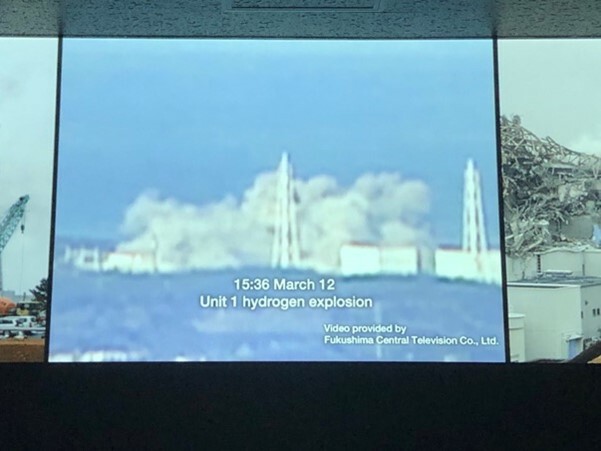

The Fukushima Daiichi workers on site at the time of the meltdowns had to cope with fears of radiation contamination and uncertainty about how to bring the situation under control in a cascading disaster that began with total loss of power on March 11, 2011 due to the massive 13 meter tsunami triggered by the magnitude 9 earthquake. This station blackout caused a cessation of reactor cooling systems and precluded automated venting of the hydrogen accumulating in the reactors’ secondary containment buildings. As the zirconium clad fuel rods heated up, they emitted hydrogen, but the staff had never practiced manual venting and had to spend valuable time figuring out how to do so due to poor training. (Cabinet 2012; Hatamura 2014; Akiyama 2016) Sato Hiroshi, one of the men in the control room during the crisis, confirmed that nobody knew how to operate the venting manually and when they eventually tried the venting system proved inoperable. (Interview April 16, 2022)

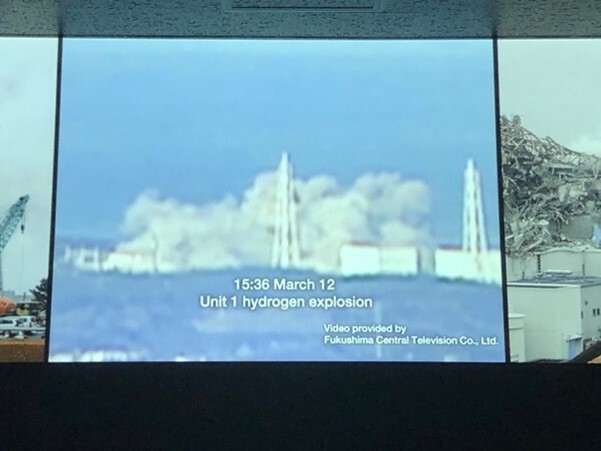

The hydrogen explosions that ripped apart secondary containment structures in Unit 1 (March 12), Unit 3 (March 14) and Unit 4 (March 15) spread radioactive debris and injured some workers, hampering the emergency response. The crisis atmosphere was also heightened by several powerful aftershocks that left staff worried about another tsunami and wondering what else might go wrong. High on that list was the possibility that the water in the spent fuel rod cooling pools adjacent to the reactor vessels might evaporate, causing a catastrophic explosion; this was the nightmare scenario because the hydrogen explosions had shredded the secondary containment housing, leaving the pools exposed to the elements. This worst-case scenario of a massive eruption of radiation with no containment would have forced any surviving emergency workers to flee the site and might have forced the evacuation of Tokyo. The plant manager Yoshida Masao had another nightmare scenario, referring to what he called a China Syndrome involving a “nuclear fuel melt through” penetrating all containment of the crippled reactors and releasing vast amounts of radiation exceeding the 1986 Chernobyl accident. (Asahi 2014) The situation was so dire he testified he felt he was likely to die. The TEPCO Archive doesn’t delve into these worst-case scenarios about what might have happened.

One can only imagine how stressful and traumatizing this on-the-job training experience was for these professionals, part of the trauma narrative of 3.11 that is not prominently featured in public discourse because they are not seen as victims of this disaster but rather those responsible for the accident. At the TEPCO Archive, I spoke with Sato Yoshihiro, one of the Fukushima 50 (actually 69 workers) who stayed on to manage the crisis while hundreds of others evacuated. (McCurry 2013) He was a control room deputy manager and involved in the failed venting efforts. There is a video interview with him at the facility recalling just how harrowing the nuclear accident was, but nothing about the manual venting. When asked, he said that the venting system failed even when they tried manually operating it and that there had not been adequate crisis emergency training. (Interview April 16, 2022) Plant manager Yoshida Masao reached the same conclusion; he and other plant workers were insufficiently trained and that was a key factor in the nuclear accident. (Asahi 2014) The Cabinet Investigation into the causes of the accident also highlights this deficiency. (Cabinet 2012, Hatamura 2014) As the sign below attests, TEPCO acknowledges this critical shortcoming.

Display at TEPCO Decommissioning Archive Center

Credit: Jeff Kingston

Since 2011 there have been significant upgrades of reactor safety hardware, but doubts linger about how well workers are trained in crisis management and operation of disaster emergency systems. Given TEPCO’s extensive institutionalized flaws and lax culture of safety along with dysfunctional internal and external communication that exacerbated the crisis, it is hard to be optimistic that sufficient improvements have been enacted in the ensuing decade. (Akiyama 2016) The Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA) has issued robust safety guidelines on restarting reactors, but has been lax on enforcing compliance, not rejecting any applications for extending the operating licenses of forty-year old plants, after asserting that this would be exceptional, and issuing approvals in cases where all safety upgrades had not yet been completed. (Kingston 2021) This appears to be yet another lesson from the 3.11 disaster about the dangers of wishing risk away that has not been taken to heart. This institutionalized insouciance about safety is why citizens have sought and won lower court injunctions blocking restarts because judges agree that the review process has been inadequate; on appeal these injunctions have been overturned but even so, the lawsuits demonstrate that the nuclear energy industry has not yet regained public trust. (Johnson, Fukurai and Hirayama 2020)

As the nuclear crisis grew increasingly dire, many plant workers drove away from the site and retreated to the Daini Plant about 12 km away, a sensible response to the evident dangers even as it raises questions about the broader implications for managing the risks of responding to a nuclear accident. The causes of this exodus are controversial, but it appears that the plant manager’s instructions may have been misinterpreted or garbled as they passed down the line. (Asahi 2014) However, Yoshida believed that the workers who decamped to safety at the Daini Plant made the right call, although he maintains he intended they retreat to the rear area of the Daiichi Plant. It’s important to note that the site is massive, about the same size as Central Park in New York. At any rate those that stayed on have been immortalized as the Fukushima 50 in an eponymous hagiographic film that focuses on how their heroic self-sacrifice saved the nation from what could have been a much more serious calamity.

It is striking how in the film Fukushima 50 (2018) the nuclear accident has been transformed into an uplifting story of bravery rather than a sordid saga of lax safety practices, regulatory capture and corporate cost cutting at the expense of public safety. (Diet 2012) It’s a deeply flawed and biased account of the nuclear accident, perpetuating myths that PM Kan Naoto was responsible for an accident that was largely the utility’s fault abetted by slipshod government oversight. (Diet 2012, Cabinet 2012, RJIF 2012) TEPCO was widely reviled following the accident and even years afterwards employees I knew were not keen to let others know where they worked. Given how important one’s job is to one’s identity in Japan, this too has been traumatizing. When the mandatory evacuation order was lifted in 2016 for Odaka, Sato’s hometown, he recalls worrying about whether he would be blamed for an accident that had transformed a once prosperous community into a ghost town. Apparently, those worries proved unfounded.

Previously, in an ill-advised act of hubris that generated a harsh public backlash, TEPCO issued a self-exonerating report about the accident in mid-2012, asserting it was a Black Swan event that was sotegai (beyond what could be anticipated) although in house researchers knew of the tsunami risk and in the 1990s TEPCO had been alerted to the dangers of a station blackout potentially leading to a nuclear accident. (Kingston 2012) However that position became untenable following three major investigations into the accident published in 2012 that emphasize TEPCO’s failure to improve disaster countermeasures despite numerous warnings, in-house and from government regulators. (Lukner and Sasaki 2013). Until October 2012 TEPCO tried to evade responsibility and muddy public perceptions by falsely implicating PM Kan but was pilloried for doing so and retracted this whitewash and issued a mea culpa at the insistence of an international team of experts brought in to review internal documents and the utility’s initial investigation. Although the Archive doesn’t explore this chapter of shirking, TEPCO’s employees probably feel victimized by the backlash generated by the attempted cover-up and the lingering image of skullduggery.

While sympathetic to the story of traumatized plant workers, the Archive is perhaps most noteworthy for what is missing. The collective and ongoing trauma of the nuclear refugees forced out of their homes, and the gutted communities and abandoned towns left behind, are not covered in the exhibits. The shared sense of betrayal among the displaced is not on display nor are the profound human consequences experienced by them and by Japanese throughout Japan who are now anxious about living in the shadow of nuclear power plants. People assumed that the scientists and officials knew what they were doing and would act responsibly to ensure safe operations, but that trust has been shattered.

Wandering into the Archive visitors encounter a progress report on decommissioning and the challenges of doing so. However, there is no reference to the spiraling cost to taxpayers now estimated to exceed $600 bn over the next four decades. (JCER 2019) Delays are expected and may extend that timeline and boost costs. The imposing F Cube in the center of the spacious first floor presents a video explaining what decommissioning work is and the status of that effort while other panels assert that there is steady progress day-by-day. It is an encouraging message that contradicts a steady stream of media reports about limited progress a decade on and various setbacks in decommissioning efforts. (Yamaguchi 2021)

Still on the first floor, we see photos of the workers engaged in decommissioning and learn about what measures they are taking at the reactors. The display on waste treatment and storage of radioactive waste overlooks the government’s so far fruitless quest to secure a permanent waste storage facility. A video panel discusses measures for treating contaminated water that TEPCO keeps in over 1,000 large storage tanks on the plant site. There is considerable controversy associated with this radiated water and what to do with it. Back in 2013 when Tokyo was bidding for the 2020 Olympics, PM Abe assured the International Olympic Committee that the water situation at Fukushima was under control, but it was untrue then and continues to be misleading now. The notorious $325 million ice wall installed to halt the flow of water passing down from adjacent hills through the reactors into the ocean has not worked as planned. (Sheldrick and Foster 2018)

There have also been numerous problems with the ALPS water decontamination system that is supposed to remove all but trace amounts of tritium so that the water can be safely dumped into the ocean. In 2018 TEPCO suddenly announced that the treatment of stored water had to be redone because the system had malfunctioned, a confidence sapping measure that further undermined confidence in TEPCO and its touted technologies. (Brown 2021)

Water Storage Tanks at Fukushima Daiichi Credit: TEPCO

Fukushima’s beleaguered fishermen are unhappy about the government approved plans to dump TEPCO’s treated/contaminated water into the ocean starting in 2023 because the 2011 accident has dashed consumer confidence in the safety of their fish. Hopes that these concerns would ebb over time have now faded with the high-profile dispute over ocean dumping that includes criticism from many Japanese citizens and domestic NGOs, international environmental experts and the governments of South Korea and China. (Brown 2021) The government has allocated JPY30 billion (US$245 million) to support the local fisheries industry and promises to buy seafood if demand declines due to consumer concerns, but these inducements have not convinced fishermen that the discharge of treated water won’t further tarnish the brand and reduce their income. (Kyodo 2022) It is common to hear locals rhetorically ask,“If the water is so safe why not dump it in Tokyo Bay?”

Visitors ascend the staircase to the second floor where there is a clock shaped pedestal of 3.11 remembrance commemorating the damage caused by the earthquake and tsunami. It is part of the exhibit: “Memory and record/Reassessment and lessons”. The video displayed nearby does open with an apology and dispassionate acknowledgement of responsibility that is an attempt to convey a level of remorse not evoked effectively by the other exhibits. But much of the video focuses on the seismic event and TEPCO’s response to the accident, conveying the sudden rupture of routine and the tensions of taking countermeasures. On a curved wall display there is a timeline of the first eleven days of the accident, another panel summarizes the countermeasures taken to manage the accident while a time series chart sketches the disaster from the time of the tsunami until cold shutdown was achieved in December 2011. Visitors also get a reactor-by-reactor review of how the accident unfolded and recreated scenes from inside the main control room for reactors 1 and 2 during the station blackout. There is also an animation including water injection efforts by fire engines at the various reactors as depicted below, a point we return to in discussing the prefectural museum.

The exhibit on the second floor that focuses on reassessment and lessons learned is striking for its brevity and breezy boosterism. Visitors learn that, “Faithfully facing up to the accident we were unable to prevent, we are determined to increase the level of safety, from yesterday to today and from today to tomorrow.” Left out is any discussion of the reasons why TEPCO was unable to prevent the accident and scant detail on how TEPCO is increasing safety other than expressing an ostensibly earnest desire to do so. Media reports about continued safety lapses and submission of falsified data in relation to TEPCO’s application to restart its Niigata nuclear power plant cast a shadow over the utility’s commitment to learning from, and acting on, the lessons of Fukushima. (Nikkei 2021). TEPCO has lost public trust (Rich and Hida 2022) and has shown limited capacity to regain it, even earning a stunning public rebuke from the NRA chair Tanaka in 2017 when he proclaimed the utility was unfit to operate a nuclear power plant. (Japan Times 2017)

Just before one descends the stairs to the exit there is an illuminating message from TEPCO asserting that, “We will pass on the genuine feedback received from the staff members who worked for the response to the accident, as ‘real voices,’ to future generations.” Here the museum is positioned as a site commemorating the trauma experienced by TEPCO’s employees and its mission of ensuring that their experiences are not overlooked. Sato is one of several employees who are featured in on-demand videos in which they share their experiences during the crisis. By highlighting the difficulties endured by plant workers, and the trauma they share with local residents, the Archive encourages a more sympathetic view of TEPCO. It is a sanitized and selective narrative that elides the damning findings of public investigations and the media, but creates the basis for “reasonable doubt” in the court of public opinion, especially as the details fade from collective memory.

Credit: Jeff Kingston

In contrast to TEPCO’s facility, Fukushima Prefecture’s Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum opened in 2020 highlights the wider human consequences of the events of 3.11, including the tsunami devastation and nuclear accident. This sleekly designed glass-walled facility located on a barren tsunami-swept area close to the coast is part of the government’s lavishly funded Fukushima reconstruction and recovery effort. Between the museum and the ocean is a derelict ruin of a house, preserved as a reminder of what the massive tsunami wrought. Inside, the spacious three story museum features displays about the derailment of people’s lives, the gutting of once vibrant communities, and the fear and uncertainty generated by the nuclear disaster. It too emphasizes lessons for the future but draws different ones than TEPCO and emphasizes the upheaval people experienced at the time, and dispiriting aftermath that lingers.

Derelict ruin and new embankments in front of museum. Credit: Jeff Kingston

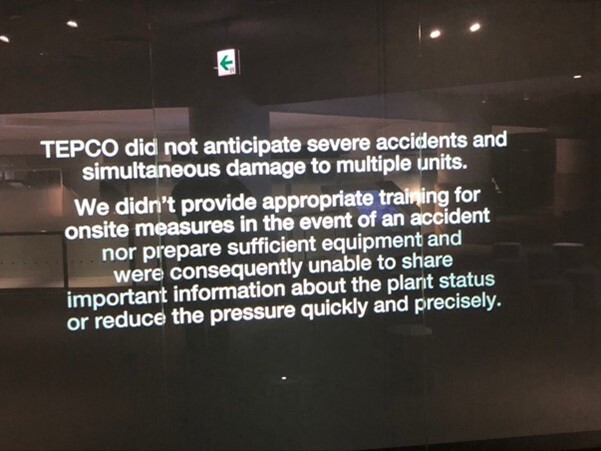

Just past the entrance an introductory short video on a large screen shows the tsunami sweeping through towns and pulverizing communities with footage of the hydrogen explosions at the Daiichi Plant that reminds visitors just how serious the situation was. In terms of public memory, the radioactive plumes bursting from the reactor buildings launched the Fukushima nightmare. The day after the third explosion, Emperor Akihito appeared in a televised address on March 16, perhaps as a gesture of reassurance but also, given how extremely rare such appearances are, ramping up anxieties. The footage of the hydrogen explosions and tsunami is repeated elsewhere in the museum. Prominent symbols of the radioactive consequences of 3.11 are also displayed such as a hazmat suit typically donned by workers where there are high levels of radiation and one of the large black plastic bags where contaminated soil is stored. As of 2022, these remain ubiquitous in the prefecture.

Credit: Jeff Kingston

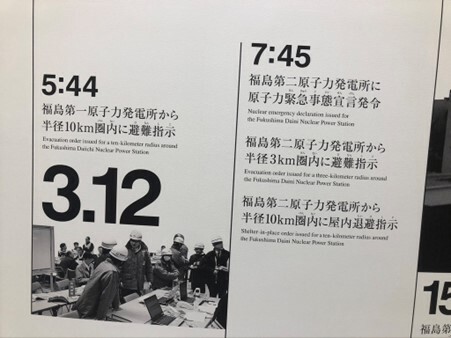

As one ascends the ramp to the second floor the wall features a series of photographs and text that provide a chronology from the safety agreement between the prefecture and TEPCO in 1969, commencement of operations in 1971 to the 13 meter tsunami that struck at 15:37 on 3.11 and the loss of AC power at 15:41 with a detailed timeline of the expanding evacuation zone that evening and the next day on March 12, including bewildering and contradictory requests for evacuations within a 10 km radius of the plant at 5:44 AM on 3.12 and about 2 hours later a shelter in place order for a 10 km radius. The next image shows Unit 1 after the hydrogen explosion at 15:36 PM later that day, a reissue of the evacuation order for those living within the 10 km radius at 17:39 PM, expanded to 20 km at 18:25 PM. One can only imagine how local residents were processing these disconcerting, rapidly shifting directives. Then on March 14 there was a second hydrogen explosion at Unit 3 followed by another early on the 15th at Unit 4, a reactor that was not even in operation at the time. Later that morning a shelter in place order was issued for a 20-30 km radius from the reactors. The chaotic government response to the unfolding compound disaster of earthquake, tsunami and major nuclear accident amplified the trauma, conveying uncertainty and incompetence at a time when the anxieties of affected people were already spiking.

March 11 Timeline of Disaster

Timeline of evacuation orders on March 11 & 12, 2011.

Credit: Jeff Kingston

The museum exhibits trace the origins and unfolding of the disaster in a more visceral and emotive set of displays than at the TEPCO Archive. The combination of video, animation, photographs, dioramas, graphs and captions provides a thoughtful assessment of what happened, how lives were affected and what lessons can be gleaned to prepare for and mitigate future disasters. The timeline of the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear accident shifts the focus to the broader impact and draws on documents, investigations and testimonies that add detail and credibility to the grim narrative. The voices, thoughts and feelings of locals are conveyed powerfully, especially the ordeal of long-term displaced evacuees. Although not at the museum, readers interested in this subject can watch Funahashi Atsushi’s powerful documentary Nuclear Nation (2013) that follows a group of nuclear refugees from Futaba to an evacuation site in Saitama, detailing the demoralizing experience.

Visitors learn about the power of rumors to distort reality and how these have been the basis for continued stigmatization affecting the lives of those engaged in agriculture and fisheries. Tackling this problem, some displays try to counter negative perceptions of Fukushima food products, and also present graphs showing increasing sales and prices.

Trends in Fukushima rice, peach and beef sales.

Credit: Jeff Kingston

Unlike the TEPCO center, the museum provides a harsh assessment of the response to the nuclear accident as residents were given conflicting information and instructions, and relocated from evacuation centers several times, adding to the stress and trauma that still haunts the nuclear refugees. There are touch screen panels that visitors can use to better understand what Fukushima’s residents have been dealing with in the aftermath of the meltdowns and the lingering impact on the psyche of people who suddenly lost everything and have had to contend with dislocation, discrimination and anxieties about potential health problems, triggering PTSD and physical ailments. Visitors see the ultrasound machine used for thyroid examinations and replicas of other devices used in monitoring food safety.

Mother and child getting medical check. Photo on display at the Greater East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum. Credit: Jeff Kingston

The museum was opened in September 2020 and updated in March 2021 just before my first visit. The updated displays were in response to criticisms from local residents and the media. The enhanced exhibits modify information on four specific issues: 1) the use of the System for Prediction of Environmental Emergency Dose Information (SPEEDI); 2) the botched evacuation of the Futaba Hospital and related deaths, 3) mandatory euthanasia of livestock, and; 4) inadequate precautions and a poor emergency response due to radiation. The updates were based on feedback from questionnaires filled out by visitors, opinions of prefectural residents and issues raised in media reports. Altogether more than 70 panels, photos and display items were added. (Asahi 2021) A new panel mentions that government officials failed to utilize SPEEDI data for residents’ evacuation, an oversight that relocated many evacuees to the hot zone of Iitate Village for an entire month, raising their radiation exposure and anxieties. The Fukushima Prefectural Disaster Response Headquarters is accused of failing to make use of the data on radiation dispersion in any systematic way and of deleting 65 of the 86 emails it received with SPEEDI updates. However, in a spiral file folder just in front of that sign there is an added explanation entitled: “SPEEDI Not Usable in Evacuation”, casting doubts on the usefulness of SPEEDI. Elsewhere I met a retired prefectural official who was closely involved in the disaster response, and he too questioned how useful SPEEDI really is and said it was not possible to use the data to plan evacuations.

There is also added text about the problems of long-term evacuations, including isolation, loss of community, fears of “dying alone” in temporary housing and the ongoing process of restoring lives and livelihoods. Another panel compares health surveys in 2014 and 2019-2020 indicating that radiation related health anxieties are abating. Parents also seem less worried about letting children play outdoors; in 2011 67% were opposed to letting them play outside compared to 3% in 2015. However, the museum did add text about the failure of the central or prefectural governments to order the distribution of iodine tablets to lessen absorption of radiation, leaving it to local initiative.

Evacuation problems. Credit: Jeff Kingston

Perhaps the saddest addition refers to the “harsh evacuation” at the Futaba Hospital that caused the deaths of at least 40 patients during and after the ordeal due to delays and miscommunication. (Nakagawa 2021)

Citing the 2012 Diet investigation report into the accident, there is a panel added in 2021 about, “the collapse of the safety myth: a man-made calamity caused by failed measures.” This safety myth was why evacuation drills had not been deemed necessary, ensuring a chaotic response when it was crucial to act effectively in a timely manner.

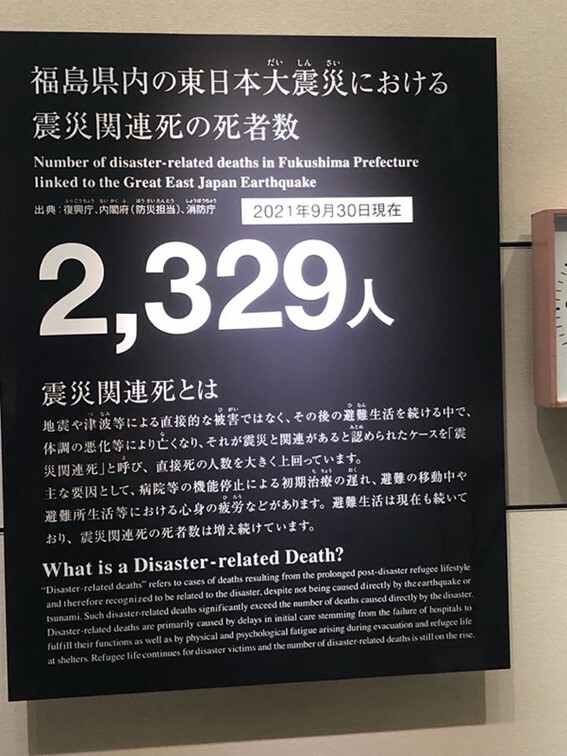

Disaster-related deaths in Fukushima. Credit: Jeff Kingston

Taking measure of the nuclear crisis in ways that the TEPCO archive avoids, the museum’s misery index also includes panels on “living with anxiety everyday” due to radiation concerns and restrictions on rice planting and the shipping of vegetables and the “collapse of communities”. Another claims 2,329 disaster-related deaths as of September 30, 2021 due to radiation impeding rescue efforts and delaying evacuations, and the negative health effects of evacuations and prolonged living in shelters. In addition, there is a panel on the “agonizing decision” to accept the construction of Interim Storage Facilities on the Daiichi site. Agonizing because the prefecture was given little choice and because locals resent that they endured a nuclear disaster as a consequence of hosting a plant that only existed to generate electricity for Tokyo. Now Fukushima is left with ghost-towns, a battered economy and reputation in tatters. It is now also saddled with TEPCO’s nuclear waste for at least two to three decades to come, if not longer, perhaps becoming the de facto radiation dump.

Also added in March 2021 is a replica of the iconic pro-nuclear sign that once spanned Futaba’s main street, declaring “Nuclear Power: Energy for a Bright Future”. It became a fixture of reporting on the nuclear accident, an ironic rebuke to the nuclear village of nuclear energy advocates. The sign was removed from Futaba in 2016 partly because the pillars had rusted but also because it was an awkward reminder that seemed to mock TEPCO, the government and the townspeople who had naively embraced nuclear energy. It now serves to remind visitors of how strong pro-nuclear sentiments were, and the appalling risks of their blind faith in TEPCO and official reassurances of 100% safety, something unthinkable in contemporary Fukushima. Oddly, the sign is displayed on an outdoor terrace at the rear of the museum, ostensibly because of its size, but staff acknowledge there are places inside or in front of the building where the sign would fit. Whatever the reason, placing this iconic symbol on a back terrace that is difficult to see from inside the museum is curious curation.

Pro-nuclear sign from Futaba and fire engine Credit: Jeff Kingston

The mandatory evacuation order for Futaba was finally lifted in June 2022. It is a ghost-town bustling with construction projects. In early April 2022, next to the still deserted street where the iconic sign had been located is a small poster of an abandoned Futaba featuring Onuma Yuji, the student who came up with the winning catchphrase in praise of nuclear energy back in 1987. In the poster he is wearing a hazmat suit with his arms stretched upward holding a placard that blocks part of the original sign. The placard declares Radioactive Ruins, featuring the symbol of radioactive flanked by the red kanji for ruins, an indictment of the naïve boosterism of his youth and the bright future based on nuclear energy that he and other townspeople had once believed in. Now, as depicted in the poster, the truncated iconic sign reads: “Nuclear Power: Radioactive Ruins Future”. Superimposed on the image is a poem expressing Onuma’s anguish about the great betrayal, and what was lost. He laments,” Oh, if only there was no nuclear accident.”

Poster in Futaba April 2022 Credit: Jeff Kingston

Until 3.11 the sign had been a source of personal pride. Although the 1986 Chernobyl accident was fresh in Onuma’s memory when he submitted his entry for the town competition in 1987, he says that living in a small town of just under 8,000 where many residents were employed by TEPCO and related to someone who was, criticizing nuclear power was a taboo. But after the reactor meltdowns he had a change of heart and in 2016 Onuma protested the removal of the pro-nuclear sign, wanting it to remain as a stark reminder of the misguided policy and wishful thinking that prevailed. (Tanaka 2016)

Visitors may wonder if the crushed mini fire engine displayed next to the sign is a metaphor suggesting TEPCO’s inadequate disaster emergency preparedness or the government’s undersized safety countermeasures. The bright red twisted heap was found in the vicinity of the museum and serves as a reminder of the heroic first responders who paid a heavy price in lives lost in the effort to rescue others along the tsunami-pulverized Tohoku coast. I was told that the Japanese Self Defense Forces offered one of their full-size fire engines that provided water for cooling the reactors and spent fuel pools during the Fukushima crisis. Apparently under pressure from TEPCO, the museum declined to display this reminder of the nightmare that almost was. As noted above, however, a display at the TEPCO Archive does show fire engines at work in the crisis response so it is not clear why it would oppose having one displayed at the museum. Perhaps the more critical context of the Museum shifts the fire engine from being a positive symbol of collective effort in managing the crisis to an indictment of TEPCO’s poor crisis response and putting fire fighters lives at risk to save the nation from the utility’s lax safety culture.

Controversially, the media has reported that the local storytellers at the Memorial Museum who relate their experiences during and after the disaster are told, at the risk of losing their jobs, not to criticize TEPCO or the prefectural or central governments when talking to visitors. (Asahi 2020) A prefectural official told the Asahi, ““We believe it is not appropriate to criticize a third party such as the central government, TEPCO or the Fukushima prefectural government in a public facility.” Some of the guides are puzzled and angry at being muzzled since these organizations have been implicated in investigations into the nuclear disaster. Guides are asked to submit scripts of the remarks they intend to give that are reviewed and edited by museum staff. Reportedly, any changes to the script, and media interviews, must be cleared with museum staff. For example, if directly asked by a visitor about TEPCO’s responsibility for the accident, guides were told to avoid directly responding and refer visitors to facility staff. The Asahi points out that, “Committees set up by the Diet and central government to investigate the cause of the Fukushima nuclear disaster issued reports that called it a “man-made disaster” and said TEPCO never considered the possibility that the Fukushima plant would lose all electric power sources in the event of an earthquake or tsunami because it stuck to a baseless myth that the plant was safe.” (Asahi 2020) In addition, there are displays at the museum that present critical information about these institutions, so it is strange to prohibit guides from expressing opinions that are documented in the exhibits. I was unable to confirm this censorship in April 2022 but did chat at length with staff who were forthright in expressing critical opinions of TEPCO and government organizations.

Conclusion

The two museums present quite distinctive narratives of the nuclear crisis. Visitors inclined to support nuclear power will exit the TEPCO Decommissioning Archive Center feeling validated, but the exhibits are unlikely to persuade critics of TEPCO or skeptics about nuclear energy safety. The Archive offers a clear and detailed explanation of what happened inside Fukushima Daiichi during the first eleven days of the accident but does not probe into the institutionalized causes of the accident highlighted in the three main investigations. (Diet 2012, Cabinet 2012, RJIF 2012) There is acknowledgement that workers were not adequately trained to deal with the cascading disaster and expressions of remorse about the consequences without explicitly detailing the nature or extent of those consequences. There is also considerable focus on decommissioning efforts but no examination of related controversies such as the more than $600 billion estimated costs over the next 30-40 years or local opposition to the building of a “temporary” nuclear waste storage facility. Similarly, there is no acknowledgment of problems with the ALPS decontamination of radioactive water, or fishermen’s anger about the planned ocean discharge beginning in 2023, the equivalent of some 500 Olympic-size pools worth of treated water now stored in over 1,000 water tanks at the plant site. The Archive diverts attention away from such problems towards a more positive outlook. TEPCO has invested lots of money in this facility and other PR efforts to improve its image and shape the 3.11 narrative. This was never going to be easy, and challenges remain, but the Archive makes the best of a difficult situation and is what one would expect. It’s one of the Fukushima tour sites, not far from the Museum and a new memorial at the Ukeda Elementary School that will attract visitors and as such an opportunity to provide different information, challenge damning narratives and influence public attitudes and memories. Given how low TEPCO’s image sunk post-3.11, over time the Archive can achieve PR goals of improving the corporate image and how its role in the disaster is remembered.

As of March 2022, the Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum has welcomed over 100,000 visitors since the museum opened in late 2020 but the pandemic has limited numbers that are only now beginning to recover. Unlike the Archive it is a stunning building in an expansive space that is more appealing for tourists and school excursions. In addition to providing extensive coverage of the tsunami’s impact, it engages various nuclear-related controversies that the Archive does not cover. Among these are the botched evacuations, especially of elderly hospital patients, the frequent evacuations and lingering trauma of the nuclear refugees, the transformation of communities into ghost towns, the daily anxieties of living with radiation, and the disaster-related deaths of over 2,300 residents. Overall, the displays convey a damning indictment of TEPCO and government institutions and as such will powerfully influence collective memories of the traumas experienced and perceptions of the organizations responsible for the man-made nuclear crisis that blighted livelihoods, families and communities in Fukushima while etching its place in global memory alongside Chernobyl.

Sources

Akiyama, Nobumasa, (2016) “Political leadership in nuclear emergency: institutional and structural constraints” in Sagan, Scott and Edward Blanchard, eds, Learning from a Disaster: Improving Nuclear Safety and Security after Fukushima. Stanford, CA: Stanford Security Studies, pp. 80-108.

Asahi (2022). “TEPCO pushes back timeline for storage tanks at Fukushima plant”, Asahi Shimbun. April 28.

Asahi (2021a) “3/11 museum updates displays of nuclear crisis to give truer picture” Asahi Shimbun, April 10.

Asahi. (2021b) “Editorial: Public’s distrust of TEPCO runs deeper than its water tanks” Asahi Shimbun. April 14.

Asahi (2020) “Don’t criticize government or TEPCO, guides in Fukushima told” Asahi Shimbun, September 23.

Asahi (2014). “Reality of the Fukushima 50 Special Report”, Asahi Shimbun.

Brown, Azby. (2021) “Fukushima Daiichi water: The world is watching or should be” Safecast, May 6.

Cabinet(2012). Cabinet of Japan Investigation committee on the accident at Fukushima nuclear power stations of Tokyo Electric Power Company. Final Report. 23 July. (accessed April 30, 2022).

Diet. (2012) The Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission. Executive Summary. Tokyo: National Diet of Japan.

Hatamura, Yotaro, et al. (2014) The 2011 Fukushima Nuclear Power Accident. Sawston, UK: Woodhead Publishing.

JCER. (2019) “Accident cleanup costs rising to 35-80 trillion yen in forty years” Japan Center for Economic Research, July 3.

Tanaka, Miya. (2016). “Creator slams removal of pro-nuclear signs from Fukushima ghost town” Kyodo News reprinted in Japan Times. March 3.

Japan Times. (2017) “Editorial: NRA’s nod for a Tepco restart” Japan Times. Oct 8.

Johnson, David, Hiroshi Fukurai and Mari Hirayama (2020). “Reflections on the TEPCO trial: prosecution and acquittal after Japan’s nuclear meltdown” Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 18:2(1) January 15.

Kingston, Jeff. (2021) “The development state and nuclear power in Japan” in Kyle Cleveland, Scott Knowles and Ryuma Shineha, eds., Legacies of Fukushima. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Kingston, Jeff. (2012) “Mismanaging Risk and the Fukushima Nuclear Crisis” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10: 12 (2) March 12.

Kyodo. (2022) “Fisheries group conveys to PM opposition to Fukushima water release” Kyodo News. April 5.

Lukner, Kerstin and Alexandra Sakaki, (2013)”Lessons from Fukushima: An Assessment of the Investigations of the Nuclear Disaster,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 11:19 (2), May 13.

McCurry, Justin. (2013) “Fukushima 50: ‘We felt like kamikaze pilots ready to sacrifice everything’ Guardian. January 11.

McCurry, Justin. (2012). “Fukushima disaster could have been avoided, nuclear plant operator admits” Guardian. October 15.

Nakagawa Nanami. (2021) “Evacuation complete with 227 patients left behind during Fukushima disaster”, Tansa (Tokyo Investigative Newsroom. March 10.

Nikkei (2021). “Japan bans TEPCO from restarting nuclear plant over safety flaws.” Nikkei, April 14.

Onitsuka, Hiroshi. (2012) ‘Hooked on Nuclear Power: Japanese State-Local Relations and the Vicious Cycle of Nuclear Dependence,’ The Asia-Pacific Journal10: 3, 1 (16 January).

RJIF. (2014) Independent Investigation Commission on the Fukushima Nuclear Accident, The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station Disaster: Investigating the Myth and Reality. (Expanded and updated English edition of the Report by The Independent Investigation Commission on the Fukushima Nuclear Accident, Rebuild Japan Initiative Foundation originally published in Japanese on 1 March 2012) London: Routledge.

Sheldrick, Adam and Malcolm Foster. (2018) “Tepco’s ice wall fails to freeze Fukushima’s toxic water buildup” Reuters. March 8.

Yamaguchi, Mari. (2021) “Fukushima Chief: No need to extend decommissioning target” The Diplomat, March 4.