Abstract. The Battle of Tsushima was fought between Japan and Russia in 1905. It was the most notable naval battle during the century before the First World War and one of the most decisive naval clashes ever. Although it has left a deep and indelible mark on both belligerents, it was only natural that the battle would remain a center point in the collective memory of the country that won it. Indeed, throughout the years before Japan’s surrender in 1945, and to a lesser extent even after, the battle continued to be the focus of commemoration and pride, possibly more than any other single battle the country had ever won or lost. Nonetheless, with the passing of time and changing circumstances, attitudes toward the battle witnessed their ups and downs much like the attitudes toward the entire war against Russia, empire, and militarism. Accordingly, the history of the battle’s collective memory can be divided into four distinct phases: the immediate response; the subsequent forty years of imperialistic expansion; the era of Allied occupation; and the years since a democratic Japan regained its sovereignty. This article aims to examine the winding road of this memory, its sources and repercussions.

Keywords. The Russo-Japanese War; the Battle of Tsushima; battleship Mikasa; Tōgō Heihachirō; war memory; Japanese militarism; Tōgō jinja

The Battle of Tsushima was fought between Japan and Russia in 1905 and has left an indelible mark on both. It was the world’s most notable naval battle during the century before the First World War and one of the most decisive naval clashes ever. From a broader historical perspective, however, it could also be seen as a flashpoint in prolonged frictions between two expanding powers. Both belligerents were rising empires that were seeking additional territories, mastery of the seas in their vicinity, and national greatness. Of the two, Russia had greater experience in foreign expansion. The fear of Russia is not a new phenomenon; it had been encroaching eastward into Asia for centuries, whereas the Japanese empire had been striving to expand in the opposite direction for only a few decades. In the early twentieth century too this country acted as an aggressor, whereas Japan, for a while, seemed to be fighting for its life and its budding empire. These differences notwithstanding, the clash between the two in 1904–5 was fierce and vital, to the extent that it would serve as the opening shot of an armed struggle that would last for another forty years.

When the two fleets met each other in the vicinity of the island of Tsushima for a final showdown, they had already been at war for fifteen months. The two belligerents were exhausted. Japan, on the one hand, had lost tens of thousands of young officers and soldiers and was required to raise further foreign loans to keep up its war efforts. Russia, on the other hand, was overburdened not only by a series of fiascos on the battlefield but also by a concurrent internal revolution, known also as the first Russian Revolution. By spring 1905, both parties were yearning for a miracle in the seas. Since October 1904, the entire Baltic Fleet—the largest and most prestigious unit of the Imperial Russian Navy—had been sailing eastward in the direction of Japan. Initially, this armada left to rescue Russia’s Pacific Fleet, which at the time was under siege in Port Arthur in Manchuria. But as this fortress fell in January 1905, the Baltic Fleet had to fight on its own. It undertook an epic voyage that has received considerable scholarly attention in later years. By late May 1905, as the Baltic Fleet was approaching Japan, the world could not miss the significance of the moment. A Japanese victory could end the war in a peace agreement, whereas a Russian victory could change the entire course of the struggle, perhaps even the fate of the Japanese Empire. As an island country, Japan could not keep a firm hold in the continent without ruling the seas in its vicinity, a fact still relevant today.

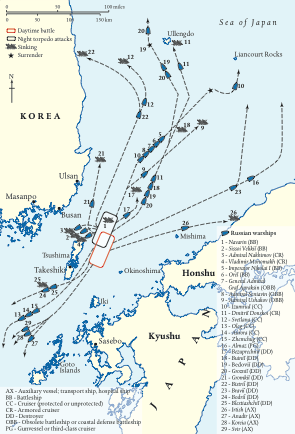

The naval battle that began to rage on 27 May 1905 and ended more than 24 hours later shocked laymen and naval specialists alike. This is not because the Japanese victory was surprising. In fact, the Imperial Japanese Navy had won almost all earlier engagements against its Russian foe. Nonetheless, no one expected such a decisive victory, and even more so, no one expected such an extensive display of Japanese superiority, both in tactics and fighting spirit.1 In the end, almost every Russian warship was sunk, captured, or interned, with only three small vessels reaching safe haven in Vladivostok. In terms of aggregated tonnage lost, captured or interned, the imbalance is even more apparent: Russia’s total losses were 198,721 tons (92.5 percent of the entire fleet) compared to a mere 265 tons lost by Japan (a ratio of 749:1). A comparison of the aggregate tonnage of the warships sunk in the battle, 97,000 vs. 265 tons, is no less astonishing (a ratio of 366:1).2 Overall, the Battle of Tsushima marked the most devastating defeat suffered by the Imperial Russian Navy and its Soviet heir in its entire history.

Map 1. The location of the battle and the fate of the Russian warships, May 27–28, 1905.

Courtesy of Oxford University Press.

The two belligerents have used different names for this naval clash (Jpn. 日本海海戦 Nihonkai kaisen; Rus. Цусимское сражение Tsusimskoe srazhenie), and have ascribed varying degrees of importance to it through the years. After all, one of them won and the other lost. But in both, this largest naval engagement of the Russo–Japanese War is still debated, still devotedly commemorated, and still triggers pride or pain more than a century after it ended. As the party that won the war and benefited from it most, it was only natural that the battle would remain a centerpiece in Japan’s collective memory. Throughout the years before Japan’s surrender in 1945, and to a lesser extent even after, the battle continued to be the focus of celebration and pride, possibly more than any other single battle the country had ever fought. Nonetheless, over time, attitudes toward the battle witnessed their ups and downs much like the attitudes toward the entire war against Russia, the Japanese empire, and the military.3 This was not necessarily because of the battle per se, but of the winding road the Japanese attitudes to the nation’s recent past have followed.

Accordingly, the history of the battle’s collective memory can be divided into four distinct phases: the immediate reactions of elation and euphoria after the battle and throughout 1905; the subsequent forty years of imperial expansion during which the battle turned into a model of naval engagement and emblem of military devotion; the era of Allied occupation when war and militarism became an absolute taboo and the commemoration of the battle was neglected; and the years since a democratic Japan regained its sovereignty when the battle regained its position as the epitome of young and pure Japan fighting successfully for its life and freedom. This article examines the winding road of this memory, its sources and repercussions.

Phase I: Relief and Euphoria: The Immediate Response (1905)

Upon hearing the news of the victory, the entire Japanese nation was filled with a sense of exultation. It was nonetheless a sober joy, and the public was—to foreign observers’ amazement—mostly able to hold back a mixture of exhilaration and relief. This general reaction was sensible as the war was still not over and by then Japan lost more than 80,000 men—the greatest military loss the nation had endured since the onset of its modernization.4 Even more importantly, the early-twentieth-century Japanese state was striving to conduct itself in a civilized and chivalrous manner and so to gain the respect and support of the leading Western powers.5 In this manner, the Japanese society followed the Judeo-Christian tradition (“Do not rejoice when your enemy falls, and let not your heart be glad when he stumbles”) but wrapped it in a partly reinvented samurai code of humbleness and self-control.6

Reflecting the proper spirit of the day, Emperor Meiji (reigned 1867–1912) composed a five-line poem that solemnly grieved for the Japanese soldiers lost in the fighting.7 Still, some could not suppress their elation. Over 100,000 people gathered spontaneously to celebrate the triumph in Tokyo’s Hibiya Park off the Imperial Palace’s moat.8 Unlike earlier lantern parades—a common sight during the conflict against Russia—the atmosphere was particularly euphoric this time around (Figure 1). Although the newspaper headlines seemed somewhat restrained, the breaking news, following a hiatus of more than two months since the land victory at Mukden, gave the crowd a solid reason to believe that the war was about to end.9

Figure 1. Parade in honor of the victory at Tsushima, 1905. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (reproduction number, LC-DIG-stereo-1s31080).

These heightened expectations notwithstanding, the Battle of Tsushima did not end the war. It did, however, prompt new efforts on Japan’s behalf for peace negotiations that were to conclude the war within little more than three months. After the Battle of Mukden, the country was exhausted militarily and financially, even as it achieved more than it had envisaged before hostilities began.10 Japan craved a lasting peace that would consolidate its accomplishments on the battlefields of Manchuria. The Battle of Tsushima reinforced this urge. With such a splendid victory in its pocket, Japan’s prospects of ending the war through peace negotiations were even greater. It was little wonder, then, that Tokyo, rather than St. Petersburg, took the first steps toward peace in the wake of the battle. On 1 June 1905, and a mere four days after the government in Tokyo received the news of victory, its United States representatives approached President Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919) and asked him to advance “his own motion and initiative.”11

Throughout that month, Japanese negotiators sought, to little avail, to exploit Russia’s naval defeat and to bring its leaders to the negotiation table. Eventually, and with Roosevelt’s support, the Japanese decision-makers resolved to occupy the large island of Sakhalin, the nearest Russian territory. The mission was given to the Imperial Japanese Navy’s (IJN) Third Fleet under Vice Admiral Kataoka Shichirō and the IJA’s newly formed 13th Division. The invading expeditionary force left for Sakhalin on 5 July 1905, and the first landing operations began two days later. The entire island fell into Japanese hands on 13 July, although Russian partisan units kept on fighting in the northern part of the island. Not until 1 August 1905 did the Russian garrison finally surrender.12

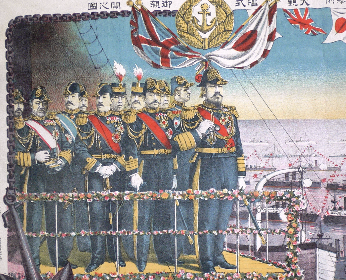

By early summer 1905, the strategic importance of a supportive world public opinion was evident. Japan’s pre-war image had improved markedly, in the United States in particular.13 It was no time for a momentary distraction or, worse, bravado and hubris. Celebrations of the victory were thus postponed again and Russian prisoners were accorded commendable treatment.14 This was certainly the lot of the wounded Vice Admiral Zinoviĭ Rozhestvenskiĭ, the commanding officer of the Baltic Fleet. On 3 June 1905, Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, the commanding officer of Japan’s Combined Fleet, visited him at the naval hospital in Sasebo. As he exemplified the Japanese spirit of chivalry and held Rozhestvenskiĭ’s hand in his hands, Tōgō said emphatically: “Defeat is an accident to the lot of all fighting men, and there is no occasion to be cast down by it if we have done our duty. I can only express my admiration for the courage with which your sailors fought during the recent battle, and my personal admiration of yourself, who carried out your heavy task until you were seriously wounded.”15 This ostensibly private visit, which took place a mere six days after the battle, was soon immortalized in a multitude of texts and visual records (Figure 2).16 Two weeks later, and in a similar gesture of civility, the Japanese authorities released the Kostroma, one of the two hospital ships which had been captured. She left for Shanghai with wounded sailors on board and then headed for Manila to collect more casualties to return to Russia.17 As modern wars are also waged in the media, such gestures could epitomize the image Japan coveted most in 1905: a victorious yet compassionate nation.

Figure 2. Admiral Tōgō pays a visit to his wounded nemesis, Vice Admiral Rozhestvenskiĭ. Source: Edwin Sharpe Grew, War in the Far East, vols. (London, Virtue: 1905), 5:160. Author’s private collection.

Once the takeover of Sakhalin was complete, the road to a peace treaty was short. With President Roosevelt serving as host, the two belligerents sent their representatives to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where a peace conference was to be convened. Roosevelt had conveyed messages to both parties stating his keenness to serve as a mediator as early as February 1905, but the Russians were adamant in their refusal, despite the Japanese government’s announcement of its readiness to negotiate in March. It was only after Russia’s defeat in Tsushima and surrender in Sakhalin that both belligerents recognized that diplomacy might be less painful than the continuation of an armed struggle. The change of mind was mostly on Russia’s side since Japan had desired to end the war already in March that year, soon after the conclusion of the Battle of Mukden. Now, at last, the Russian negotiators were willing to accept the majority of Japanese demands. On Tsar Nicholas II’s (reigned 1894–1917) strict insistence, however, they rejected the claim for an indemnity entirely and offered their recognition of Japan’s control of the southern half of Sakhalin instead. The Japanese surprised the world by accepting the Russian offer and signing the Treaty of Portsmouth on 5 September 1905, an act which ended the 19-month war.18

The Japanese public received the news with a shock that exceeded the relief of ending the war. Unaware of the military and economic strain the long war exerted on the nation, it had expected Russia to yield to all Japanese demands. Anger at the terms of the agreement, and the absence of any reparations in particular, was so deep that newspapers used the term ‘betrayal’ in discussing it.19 In the port city of Sasebo, Russian prisoners of war were surprised to see “not a single flag” among people “so fond of beflagging their houses.”20 On the day the treaty was concluded, some 30,000 demonstrators gathered in Hibiya Park in Tokyo. Their protest soon turned into a rampage (the Hibiya Riots), and martial law was declared in the capital. Four months later, the lingering public unrest precipitated the collapse of Prime Minister Katsura Tarō’s cabinet.21

In spite of this sour denouement to the war, few in Japan at the time doubted the war was a success story.22 When, on 20 December 1905, the Combined Fleet was dispersed, very few military units in Japan were as venerated. If asked, ordinary Japanese pointed to the Battle of Tsushima, and possibly to the seizure of Port Arthur, as the war’s climax. Two months earlier, on 21 October 1905, the Japanese media had marked the centenary of Admiral Horatio Nelson’s death in the Battle of Trafalgar. In Yokohama, a memorial banquet was attended by both a British admiral and Admiral Tōgō.23 Since the conclusion of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1902, Britain had been Japan’s foremost ally and played a key role in its naval preparations before the war.24 And yet, the sudden public interest in Nelson was self-serving too, since the domestic media, much like the foreign press, hailed Tōgō as his true heir, thereby placing Japan and Britain on a similar footing.25 The timing was both perfect and intentional. A day later, on 22 October, and a little more than a month after the war ended, Japan celebrated the triumphal return of its own fleet. By then the public clamor that had erupted in Hibiya had subsided, and some of the old humdrum routine was restored. The fleet’s return represented the climax of a whole week of celebrations imbued with symbolism, including a visit by Tōgō to the Ise Grand Shrine—Shinto’s holiest and most important site.26 During the first day of the celebrations, Tōgō, on a black horse, passed under a triumphal arch erected in the center of Tokyo and was welcomed by a huge cheering crowd (Figure 3). On the same day, the admiral also paid a visit to the imperial palace, where he reported on the naval operations during the war to Emperor Meiji.

Figure 3. A rare welcome: Admiral Tōgō’s triumphal return to the Japanese capital, 22 October 1905. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (reproduction number, LC-USZ62-68815).

The next day, the emperor and the admiral joined a crowd of more than 150,000 enthusiastic spectators in the city of Yokohama and inspected a triumphal naval review. With 146 warships in attendance, including several captured Russian ships, it was the largest review Japan had ever seen.27 Sailing onboard the imperial yacht, the Admiral Tōgō briefly introduced each ship and its wartime record and included some of the recently captured Russian battleships (Figure 4). Conspicuously missing in the celebrations was the admiral’s flagship throughout the war, the battleship Mikasa. This was because six days after the conclusion of the Treaty of Portsmouth, and while moored at the naval base in Sasebo the ship was suddenly engulfed in a fire that led to the explosion of its rear magazines; she subsequently sank.28 The loss of the ship shocked the nation, as did the deaths of 339 of its crew. Rozhestvenskiĭ sent his condolences from his prison camp. Tōgō replied laconically: his grief was inconsolable.29 The eight who had died on board the Mikasa during the Battle of Tsushima paled by comparison. It took almost a year until the ship was refloated, and another two to bring her back to active service, but she would never regain her earlier position, serving mostly in coastal defense and support duties. Few could imagine then that this victim of a terrible accident would become Japan’s primary monument to the battle. This mishap apart, the IJN had much to be proud of. From its perspective, the Russo–Japanese War was a success story, and the Battle of Tsushima was unquestionably the conflict’s single most important battle.

Figure 4. The grand imperial naval review: Emperor Meiji (on the right), Admiral Tōgō (second from the left), and prominent military figures inspecting the Japanese fleet, 23 October 1905. Courtesy of Prof. Sven Saaler (private collection).30

The end of the war found the IJN larger than ever. In absolute terms, it increased its size substantially by incorporating several Russian battleships, as well as a number of newly built capital ships of its own.31 In relative terms, it rose to fifth place among the world’s largest naval forces, and thus regained the position it had held between 1901 and 1903.32 In qualitative terms, too, the IJN gained valuable combat experience and a degree of self-confidence which affected its ambitions overseas and its conduct in subsequent inter-service competition at home. The combat success at Tsushima, and the huge popularity of the navy and Tōgō immediately after the war, induced IJN leaders to promote a navalist agenda, which meant the IJN’s further expansion. Highly publicized naval reviews resembled the pattern set in October 1905 and were reinforced by ceremonies held during the domestic launching of warships and in books and journals.33 Images of the battle of Tsushima and its participants would remain an important vehicle in the navy’s public affairs and memorabilia for years to come.34

Phase II. Pride and a Model: The Imperial Era (1906-45)

As 1905 ended, and in the four decades until Japan’s surrender at the end of the Second World War, Tsushima was lauded as the country’s ultimate naval victory. On 27 May 1906, the IJN celebrated Navy Day for the first time (Jpn. Kaigun kinenbi), and continued to do so until 1945.35 Initially, the anniversary was celebrated on a large scale, but public interest flagged quite quickly.36 Moreover, from 1910 onwards, improving diplomatic relations with Russia helped to tone down further the celebrations.37 Still, in the collective consciousness, the prominence of the battle only grew with the passage of time.38 This was the result of a constant barrage of attention the battle received in books, articles, and school textbooks. In addition, imperial Japan built tangible monuments to the battle. The first of these was a stone memorial erected in 1911 near the coast of Tsushima Island where 143 survivors of the cruiser Russian Vladimir Monomakh had landed and were helped by people of the village of Nishidomari.39 Quoting Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō’s four-character poem 恩海義喬 (Jpn. onkai gikyō; “sea of grace, righteousness is high”) and praising those villagers’ virtue, this first site of memory was also Seen as a solemn monument of reconciliation (figure 5).

Figure 5. The Memorial Monument to the Battle of the Sea of Japan in Kamitsushima (1911).

Source: Author.

More than any monument or ceremony, however, it was Admiral Tōgō who served as a living reminder of the great triumph during most of this era. With time, his image transcended that of any other figure who took part in the battle, and even the entire war, including Emperor Meiji himself. Tōgō’s rise to fame was not always a foregone conclusion. During the first year of the war, the Japanese state and the navy had highlighted the heroism of Lieutenant Commander Hirose Takeo (1868–1904), who had died during an attempt to sink a blockship at the harbor entrance of Port Arthur. Following his death, Hirose received a state funeral in the capital and was made one of two War Gods (Jpn. Gunshin).40 Alongside Hirose’s heroism, the living Tōgō, much like the conqueror of Port Arthur, General Nogi Maresuke (1849–1912), became a symbol of staunch military leadership. After the war, Tōgō was made chief of the Naval General Staff in December 1905, naval councilor in 1909, and gensui (equivalent to fleet admiral) in 1913. Together with Nogi, he received almost every possible domestic honor, including the title of count in 1907. He also received widespread foreign recognition. Among other honors, Tōgō was made a Member of the British Order of Merit in 1906 and was welcomed as a hero during a state visit to the United States in 1911 (Figure 6). In 1926, he was awarded the Collar of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum, an honor which, at the time, was only shared with the Emperor and Prince Kan’in Kotohito.41

Figure 6. Admiral Tōgō on a visit to the Naval Academy, Annapolis, 1911. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (reproduction number, LC-DIG-ggbain-09525).

After General Nogi’s ritual suicide in 1912, Tōgō took charge of the education of Crown Prince Hirohito, the future Emperor Showa (reigned 1926–1989). Unlike Nogi, whose victory at Port Arthur was attained with a tremendous loss of life that resulted in public criticism after the war and was probably the main reason for his suicide, the admiral’s triumph was anything but controversial. This fact, along with Tōgō’s longevity, helped to cultivate even further the myth of the battle, and of his own personality.43 A major agent in promoting his image as the savior of the nation was Ogasawara Naganari (1867–1958), the de facto official historian of the IJN until its demise in 1945. Ogasawara was a prolific writer, and a close confidant of the admiral since the first war against China in 1894–95.44 Furthermore, Tōgō did not intend to remain a mere symbol and became increasingly militant during the 1920s. Joining the opposition to the Washington Treaty and wielding a strong influence upon his former disciple, Emperor Shōwa, the old admiral became even more powerful during the last decade of his life.45 He was made a marquis on his deathbed in 1934, was awarded a state funeral, only the tenth such ceremony since the Restoration of 1868, and was buried next to a former monarch, Emperor Taishō (reigned 1912–1926). By then, he was considered one of Japan’s greatest modern military leaders and its most prominent naval figure of all time.47

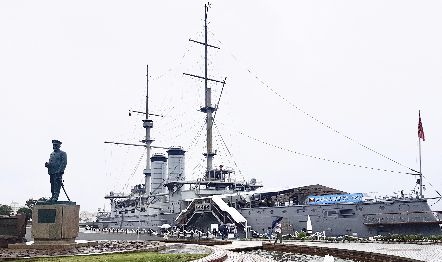

Still, even the deep reverence for Tōgō and the erection of a monument on the Island of Tsushima were not a genuine substitute for a central memorial site for the battle. This commemorative function was fulfilled by the battleship Mikasa—‘Tōgō’s flagship during the battle. The trigger for the decision to turn her into a memorial site was the Washington Naval Conference of 1921–22. The Conference’s setting of quotas on the aggregated displacement of capital ships in each major fleet unintentionally brought about the Mikasa’s end as an active navy vessel. Although the decision was made in a period when the popularity of the military in Japan was reaching its nadir, the decommissioning of this obsolete ship in 1923 prompted an almost instant media campaign for its preservation.48 The Mikasa Preservation Society was established a year later, with Tōgō as its honorary chairman.49 Its main aim was to lobby for the ship’s transformation into a memorial site and thereby to inspire the public with her historical value, and cultivate the national spirit.50

The year 1925 thus marked a new phase in the Mikasa’s history. The preservation of the ship was now made official government policy, and this was followed by an appeal to the leading powers to allow it to be retained as a monument, despite the requirements for naval reductions.51 With their approval, the old flagship was towed to its ultimate berth in Yokosuka, very close to the naval base it had served, and about one hour’s train ride away from Tokyo, in June 1925. The site’s opening ceremony was held on 12 November 1926 in the presence of Crown Prince Hirohito, Tōgō, and some 500 other attendees (Figure 7).52 Encased in concrete, the Memorial Ship Mikasa (Jpn. Kinen-kan Mikasa) instantly became the main commemoration site for the naval chapter of the war against Russia in general, and the Battle of Tsushima in particular. Its popularity grew and reached a zenith before the Pacific War (1941–45), when more than 500,000 visitors a year made the pilgrimage to see it (Figure 7).53

Figure 7. The Memorial Ship Mikasa, c. 1930, Yokosuka. Starting in 1925 and during the remaining prewar period, the ship became the main memory site of the Battle of Tsushima and a major tourist attraction. Source: Wikipedia Common.

Another site of memory for the battle was inaugurated in Fukutsu, Fukuoka Prefecture, in the year Admiral Tōgō died in 1934 (Figure 8).54 By this point, Japan had witnessed incessant endeavors to revive the memory of the Russo–Japanese War as a tool for enhancing patriotism and militarism.55 Within these efforts, the Battle of Tsushima had become a powerful motif in moral education, and appeared in virtually every school history textbook as a significant catalyst of bushidō-related indoctrination.56 The monument in Fukutsu was a tangible contribution to this trend. Built in a warship-like concrete form, with a turret directed at the Tsushima Strait, the monument was the personal initiative of Abe Masahiro, a local veterinarian who had taken part in the battle. At the planning stage, Abe intended to call the monument “Russo-Japanese War Victory Memorial,” but Tōgō opposed this, saying “I cannot endure the word Victory when I contemplate about the soldiers of both sides who turned into the precious sacrifice of their country.” Thus, eventually, the site was called “The Battle of Tsushima Memorial Monument.” Abe designed the conspicuous edifice to specific dimensions: its height and width are 38 and 5 shaku, respectively, and its mast measures 27 shaku.57 Together, these measures stand for the date of the battle, that is May 27, 1905 (Meiji 38). The monument also displays a copper relief of the admiral along with the inscription 各員一層奮励努力 (lit. [let] each man do his utmost [strenuous effort]).58

Figure 8. A monument memorializing the Battle of Tsushima, Fukutsu, Japan, 1934.

Source: Wikipedia Common, photographer: Jun Okubo.

Tokyo, where Tōgō was interned in 1934, however, had to wait a little longer for a monument of its own. Ultimately, it was in this city that the fleet admiral was bestowed, six years after his death, with one of the greatest and rarest tokens of recognition that can be conferred posthumously on a Japanese when he was officially deified and publicly worshiped as a god (kami) as part of the newly formed State Shinto-sponsored nationalist pantheon. To this end, and with the help of donations from the public and naval associations, Tōgō Shrine (Jpn. Tōgō jinja) was erected in Harajuku District, at the very center of the capital. The shrine was ceremonially dedicated on the Navy Anniversary Day of 1940 in the presence of Fleet Admiral Prince Fushimi Hiroyasu.59 The driving force for its construction was public pressure on the Navy Ministry, the establishment of an association to this end, and extensive donations. In a period of escalating inter-service rivalry, the IJN was particularly open to persuasion. With a shrine devoted to its greatest admiral, it could keep pace with the honor bestowed upon the IJA General Nogi Maresuke and his wife Shizuko, to whom the Nogi Shrine had been dedicated in Tokyo as early as 1923. Eventually, the two shrines shared a tragic fate. On 25 May 1945, exactly two days before the battle of Tsushima’s fortieth anniversary, both were burnt to the ground as a result of an American air raid.60

On the eve of the Pacific War, the Battle of Tsushima represented an enduring legacy for virtually any senior IJN officer. Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku (1884–1943) and Vice Admiral Nagumo Chūichi (1887–1944) may serve as cases in point. For the former, the commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet and mastermind of the attack on Pearl Harbor, it was the most memorable and formative combat experience he had experienced, at least until December 1941. Thirty-six years earlier, the 21-year-old Yamamoto had been an ensign on board the cruiser Nisshin, which formed part of the 1st Battle Division. When the ship’s forward turret was hit by a Russian shell during the initial engagement, he was injured in his leg and lost two fingers.61 In subsequent years, Yamamoto stuck to the orthodoxy of a single decisive battle dominated by battleships. With this mental imprinting, and despite being the former chief of the Naval Aviation Department and a prophet of carrier warfare, this illustrious admiral, much like the rest of the IJN top echelon, still regarded aging American battleships as his key adversary in the impending naval clash as late as the eve of the attack on Pearl Harbor.62 Thus, he carried through his preemptive aerial strike despite the absence of the American carriers. Obviously, he had other strong motives for this assault, but his Tsushima mindset cannot be precluded. Symbolically as well, and in reference to the famous Z flag (Jpn. zetto-ki) which Tōgō hoisted on the Mikasa in 1905, the attack on Pearl Harbor was referred to as Operation Z during its planning.63

In fact, this emblem of Tsushima was present during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Under Yamamoto’s exhortation, Vice Admiral Nagumo, who 36 years earlier had served as a young officer in (the future prime minister) Suzuki Kantarō’s 4th Destroyer Division, and now was leading Japan’s main carrier battle group, ran up the same pennant on his flagship, the carrier Akagi (Figure 9). According to some sources, it was the original one used aboard the Mikasa.64 Shortly before, Nagumo read aloud an imperial rescript written before the fleet’s departure by Emperor Shōwa. This text too was reminiscent of Tsushima: “The responsibility assigned to the Combined Fleet is so grave that the rise and fall of the Empire depend upon what it is going to accomplish.”65 Six months later, it was all too symbolic, but somewhat unplanned, that Nagumo chose the 37th anniversary of the battle, Navy Day on May 27, 1942, as the date his fleet would weigh anchor and leave for another battle at Midway. Eleven days later, the battle was lost. It would become a turning point in the Pacific War and the beginning of the IJN’s downfall.66

Figure 9. The Z-flag is hoisted onboard the carrier Akagi during the attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941. Source: Wikipedia Common.

Phase III. Forced Amnesia: The Occupation Era and Its Aftermath (1945-57)

The interest in the battle of Tsushima diminished abruptly upon Japan’s surrender in 1945. The nation was at first preoccupied with basic survival, and its long-standing focus on militarism and heroism was soon replaced by democratic ideals and a pacifist ethos under American indoctrination and censorship. In this respect, the encounter came to be regarded as another stepping-stone on the path leading to the Pacific War, and the nation’s ultimate defeat. Hence the battle was ignored and its memorial sites were neglected during the first decade of post-war Japan. The Tōgō Shrine remained in ruins and the Memorial Ship Mikasa was pillaged by Allied soldiers upon their arrival in September 1945. Adding insult to injury, the Allied occupation authorities decided to remove the ship’s masts and some of her guns a few months later.67 As the Mikasa Preservation Society was disbanded soon after the war ended, there was no one to guard the memorial ship. It did not take long before it turned into a recreational site for US army soldiers, with a dancing hall (“Cabaret Togo”) in her central structure, as well as, at a later time, a sea life-themed aquarium at her stern (Figure 10).68 Even after the occupation had ended, The Japanese government and the municipality of Yokosuka showed little care for the shrine, or for the Mikasa.

Figure 10. The abandoned Memorial Ship Mikasa as “Cabaret Togo,” c. 1950.

Source: Author’s private collection.

Curiously, those who seemed the most concerned with the fate of the ship during this phase were foreigners. Their views and attempts to salvage her and other relics of the battle enabled concerned Japanese to take firm action in a period of spreading pacifist ideals and incertitude about any notion of militarism. In this context, the ship’s decline reached a crossroads in 1955—a year after the establishment of the Japan Self-Defense Forces. During that year, the editor of the English-language Nippon Times received a letter concerning the ship’s abysmal state.69 The writer of this letter was a Philadelphia businessman named John Rubin, originally from Barrow-in-Furness in Britain, the town in which the Mikasa had been built.70 Having observed the ship’s launch in 1900 at the Vickers Naval Construction Yard, Rubin asserted that she was to the Japanese what HMS Victory was to the British.

The publication of the letter led to a minor public buzz about the state of the ship. It also provoked a detailed and sympathetic response by a retired admiral, Yamanashi Katsunoshin (1877–1967), the president of the recently established Japan Naval Association (Jpn. Suikōkai).71 At that juncture, the idea of bringing the Mikasa back to its pre-war glory was still not only a matter of foreign pressure or personal whim but also of associations with prevailing attitudes toward the bellicosity of the country’s recent past. Indeed, the IJN was seen as having opposed the Imperial Japanese Army’s (IJA) rash plans to challenge the West, or at least as having attempted to restrain them. It was the outcome of a simplistic tendency born soon after Japan’s surrender, and which remained strong even after the end of the Allied occupation, to distinguish between the ‘good navy’ and the ‘bad army’.72 Furthermore, the Russo–Japanese War was also viewed as the last major conflict Japan had fought to achieve justified ends.

In his capacity as the president of the Suikōkai, Admiral Yamanashi saw the restored ship as becoming a major memorial site for more than the Battle of Tsushima. Instead, by focusing on the service’s heyday, the ship could be a memorial for the IJN as a whole. Aware of the need for public support, Yamanashi handed the public campaign for the restoration project to Itō Masanori (1889–1962), Japan’s leading naval affairs journalist.73 A year later, on the 51st anniversary of the battle, Itō launched the campaign with a commemorative article. Published in one of Japan’s leading newspapers, it highlighted the ship’s significance and the global impact of the victory at Tsushima. Subsequently, Itō and others were able to enlist the support of one of the Yokosuka city councilors, whose naval base had been hosting the United States Seventh Fleet’s headquarters since 1945. They also approached several leading American naval officers, including Admiral Arleigh Burke (1901–1996), Chief of Naval Operations, and the aging Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz (1885–1966), who had felt a deep admiration for Admiral Tōgō since their meeting more than half a century earlier.

Nimitz’s acquaintance with Tōgō went back to the time of the Battle of Tsushima. Upon graduating from the Naval Academy in January 1905, he had sailed aboard the battleship Ohio to East Asia and followed the clash in the Sea of Japan closely. The Ohio had reached Japan shortly after the battle and had participated in celebrations. Still a midshipman, Nimitz attended a garden party for Tōgō at the Imperial Palace, and upon his own invitation enjoyed “a brief but cordial conversation and a ceremonial sip of champagne” with the illustrious admiral. The young Nimitz never forgot this gesture. During a visit to Tokyo in 1934, by then a captain, he was invited to attend Tōgō’s formal state funeral, as well as a private ceremony at the admiral’s home. Eleven years later, on 2 September 1945, the same day he attended the surrender ceremony in Tokyo Bay, Nimitz also paid a visit to the Mikasa. Appalled by the state of the ship, whose artifacts were already pillaged as souvenirs by American servicemen, the fleet admiral ordered a marine guard to be placed at the site.74

Phase IV. Lingering Honor and Shameless Ideal: The Postwar Independence Era (1957-present)

The era of amnesia drew to a close twelve years after the end of the war. While naval enthusiasts were busy with their plans for the restoration of the Memorial Ship Mikasa, a film on the Russo–Japanese War heralded a new era. Thereon, some wars, particularly Japan’s war against the West, were to be forgotten or regretted, while others—such as Japan’s war against Russia—could be remembered with pride. Entitled Meiji Tennō to Nichiro dai sensō (Emperor Meiji and the Great Russo–Japanese War), it portrayed the major events of the war, including the Battle of Tsushima.75 Released on the Emperor Meiji’s birthday, the film was hailed as the country’s first CinemaScope film, and achieved overwhelming box office success.76 It had the highest number of viewers (around 20 million) and was the highest-grossing film in Japanese film history to that point. Incredibly, its viewership record was only broken 44 years later with the 2001 release of Miyazaki Hayao’s animated fantasy film Spirited Away (Jpn. Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi).

Ordinary spectators seemed to approve of the film’s dualistic message. It skillfully wrapped its displays of a still somewhat censored militaristic spirit with early-century respected values, and a strong sense of patriotism (see Figure 11). Even foreign observers could not remain blind to these dialectics. The Tokyo correspondent of The Times, for example, noted: “What is the secret of this film’s success? Critics emphasize that audiences are deeply stirred by the spectacle constantly before their eyes of the Emperor, military, government, and people, one in mind and spirit, working for the greatness of Japan. In a sense, the film is militaristic; but its militarism is that of Admiral Togo, or General Nogi—not of Tojo and the leaders of the last war.”77

Figure 11. A studio still snap the 1957 Japanese film Meiji Tennō to Nichiro dai sensō.

Source: Wikipedia Common.

A year later, in 1958, the Mikasa Preservation Society was reestablished after 13 years of inactivity. Nonetheless, American support remained an important factor in the actual restoration of the ship. In 1959, Japan’s leading monthly Bungei Shunjū published an article written by Admiral Nimitz, in which he argued that the Mikasa would become a monument to a key turning point in Japanese history and the global recognition of this fact.78 Nimitz’s donation of the fees received for the article to the cause was replicated by members of the Seventh Fleet in Yokosuka and domestic supporters. Among other supporters, the Japan Sumo Association toured the country to raise funds. Altogether more than half a million Japanese contributed to the project.79 With this enthusiasm and financial support, the ship was subsequently restored and opened to the public on the 1961 anniversary of the battle (figure 12).80

Figure 12. The reopened Memorial Ship Mikasa with the statue of Admiral Tōgō in its front, 2019.

Source: Author.

By then, the Tōgō Shrine had witnessed a similar recovery. With a flurry of donations, including Nimitz’s royalties from the Japanese translation of his book The Great Sea War,81 the shrine was rebuilt alongside a small museum devoted to the admiral’s memory and to the Battle of Tsushima.82 The entire site was reopened in 1962, the same year as the Nogi Shrine, and a year after the Memorial Ship Mikasa’s.83 Nine years later, another Shinto shrine for Tōgō was established, this time in Fukutsu, Fukuoka Prefecture, next to the monument memorializing the Battle of Tsushima. Planned as early as 1922 by Abe Masahiro, the man behind the memorial monument in the same location, the shrine holds two annual festivals, one on the day of the battle (May 27) and another on Tōgō’s birthday (November 22).

A boom of war films and historical fiction novels in the late 1960s also helped bring the battle back into the Japanese mainstream. In this regard, the harbinger of change was Maruyama Seiji’s 1969 film Nihonkai dai kaisen (Great Naval Battle of the Japan Sea) which focused exclusively on this naval battle for the first time. Although it was probably inspired by the centenary celebration of the Meiji Restoration a year earlier, there was also a financial motive.84 By featuring the pre-eminent actor Mifune Toshirō in the role of Tōgō, Tōhō studios sought to repeat the box-office success of its film Nihon no ichiban nagai hi (Japan’s Longest Day) two years earlier. Given the cult of the “good navy,” naval themes became highly popular, with Rengō kantai shirei chōkan Yamamoto Isoroku (Yamamoto Isoroku, Commander in chief of the Combined Fleet) screened a year earlier, the American-Japanese co-production Tora! Tora! Tora! a year later, and Okinawa kessen (Decisive Battle for Okinawa) two years after that (1971).85

The most important cultural reference to the battle in this new era, however, appeared in written form. Entitled Saka no ue no kumo (Clouds Above the Hill), and serialized in the national daily Sankei Shimbun between 1968 and 1972, this novel told the story of the Russo–Japanese War, devoting a full volume to the battle.86 One element in the book’s success was undoubtedly the identity of its novelist—Shiba Ryōtarō (1923–1996), Japan’s most prominent and popular author of historical fiction to this very day.87 But additional crucial elements were its content and context. During a period when the Japanese public began to feel confident enough to re-examine its sour experiences during the so-called Fifteen Years War (1931–45), Saka no ue no kumo told the story of a just war and of patriotic officers. Epitomizing Shiba’s passion for the bushido values of patriotism, loyalty, and selflessness, the novel focused on the lives and exploits of three non-fictional figures: the brothers Akiyama Yoshifuru and Akiyama Saneyuki, and their friend, the poet and literary critic, Masaoka Shiki.88 The storyline follows their life from childhood to a climax during the Battle of Tsushima. Shiba’s multi-volume epic triggered a revival of public interest in Tsushima. Tōgō, for example, was the topic of no fewer than three new biographies published within four years of each other.89 The same year in which Shiba’s final volume appeared also witnessed the publication of Yoshimura Akira’s (1927–2006) Umi no shigeki (Historical Drama of the Sea). This novel told the story of the naval struggle during the war and the Battle of Tsushima, in a semi-documentary style, and stressed the Russian perspective even further.90

In the past two decades, the most notable literary contribution to the battle’s commemoration has been in the form of manga. A seminal graphic novel of this genre is the work of illustrator Ueda Shin and writer Takanuki Nobuhito, Jitsuroku Nihonkai kaisen (The Record of the Naval Battle of Tsushima), which was serialized in 2000.91 A year later, Egawa Tatsuya’s (1961–) Nichiro sensō monogatari (A Tale of the Russo–Japanese War) became a hit.92 The story is concerned with the rise of Naval officer Akiyama Saneyuki and, despite stopping at the Sino–Japanese War, hints at the crowning glory of Tsushima a decade later in its subtitle, based on Akiyama’s famous meteorological message shortly before the battle: “The weather is fine but the waves are high.”93 By all accounts, the success of both works amplified the popularity of Saka no ue no kumo among a new and younger audience.

Another indication of popularity was the city of Matsuyama’s decision to open a museum commemorating the novel (the Saka no Ue no Kumo Museum) in 2007, which is housed in a building designed by the renowned Japanese architect Andō Tadao.94 A few years later and four decades after its initial publication, Shiba’s novel reached a second peak in an adapted visual form. As a result, after years of wavering, apparently on account of the novel’s militaristic content, NHK, Japan’s national public broadcasting organization, decided to produce a series (Jpn. taiga dorama) based on it. Airing between 2009 and 2011, and culminating in a final episode entitled The Battle of Tsushima (Jpn. Nihonkai kaisen), this 13-episode production was the most expensive and most elaborate period drama NHK had ever produced. Its popularity was high as well, reaching an average viewership rating of no less than 19.6 percent (of the total viewership) in two of its episodes.95

Domestically, and even more so among its neighbors, Japan’s modern wars and the period of Asian imperialism have remained controversial issues. And yet, the spectacular economic success and rising confidence the country experienced in the 1980s also revived interest in the pre-war past in official circles.96 In 1988, the Japanese Ministry of Education included Tōgō in a list of historical figures recommended for primary and secondary school texts.97 The ministry’s decision attracted strident criticism, but the Russo–Japanese War has been gradually accepted as a war of self-defense, and the Battle of Tsushima as its glorious centerpiece.98 Recent Japanese school textbooks on modern history, national and global alike, often refer to the battle and its significance, but without the stress on its heroic virtues as was the case with pre-war textbooks.99 The climax of this post-war fascination with the battle occurred around its centenary in 2005. By then, the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) had established the Russo–Japanese War as an ethical epitome of the defensive role this service is expected to fulfill. The crown achievement of that war, in the JMSDF’s view, was unquestionably Tsushima. It is not surprising, then, that the JMSDF stood behind the major commemorative events of the anniversary. The two most important of these were held on 28 May (not to be confused with the pre-war Navy Anniversary Day a day earlier): one onboard the Mikasa, with some 2,000 guests in attendance, and the other at sea, on the site of the battle.100

Ever since, brochures sold at the Memorial Ship Mikasa have presented her as one of the “Three Great Historical Warships of the World,” alongside HMS Victory in Portsmouth, and the USS Constitution in Boston.101 This internationalist sentiment does not end there. The JMSDF also dispatched its training squadron to Portsmouth in the United Kingdom to attend the International Fleet Review held off Spithead in the Solent on 28 June 2005, thereby associating the bicentenary celebrations of the Battle of Trafalgar with the centenary of the Battle of Tsushima.102 The same year saw the homecoming of the Z flag which Tōgō had hoisted aboard his flagship Mikasa. Some six years after the battle, when the admiral attended the coronation of King George V, he had donated the flag to the Thames Marine Officer Training School, in which he studied in the early 1870s. As the centenary celebrations of the battle approached, the Marine Society, which inherited the flag, agreed to lend it permanently to the Tōgō Shrine.103 By then, the shrine had long regained its position as a major and accessible site of the battle’s memory and commemoration. Since its retrieval, the flag has turned into a major symbol of the shrine, and copies are its best-selling memorabilia (Figure 13). The Z flag eventually made it back to the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF), when the guided-missile destroyer Chōkai hoisted it during a Japan-US joint military training drill in October 2011.104

Figure 13. Tōgō Shrine displaying the Z flag, 2019.

Source: Author.

Since the centennial celebrations of the battle, its memory has been used in Japan to augment the relations with Russia. The focus of this commemoration activity has been the humanitarian treatment of the Russian survivors and the commandeer of the Baltic Fleet in particular. In November 2005, Vice Admiral Zinoviĭ Rozhestvenskiĭ great-grandson, Zinoviĭ Spechinskiĭ, was invited to Japan. In a ceremony held in Sasebo, in front of the hospital where the wounded admiral had been take care of, Spechinskiĭ shook hands with Admiral Tōgō’s great-grandson, the JMSDF Captain Tōgō Hiroshige, and the two planted trees. A year later, a new memorial site for the battle was unveiled on Tsushima Island. Known as the Japan-Russia Friendship Hill (Jpn. Nichiro yūkō no oka), it is located next to the old Memorial of the Battle of the Sea of Japan. At the center of this outdoor site, there is a huge relief depicting Admiral Tōgō visiting the wounded Rozhestvenskiĭ in Sasebo. In addition, there is a board nearby carrying the names of all those killed in the battle, Japanese and Russian alike (Figure 14).105 On the eastern side of the Tsushima Strait too, a new memorial was inaugurated in 2013. Facing the site of the battle, this memorial for the dead (Jpn. Nihonkai kaisen senshisha ireihi) is on the small island of Ōshima, Fukuoka Prefecture. Like on the Japan-Russia Friendship Hill, the text is written both in Japanese and Russian and mentions “the 4,830 on the Russian side and the 117 on the Japanese side” who sacrificed their lives.106

Figure 14. A monument for “Peace and Friendship”: a relief depicting Tōgō visiting the wounded Rozhestvenskiĭ, Tonosaki Park, Tsushima Island. Source: Author.107

The attempts to use the memory of the battle for improving the contemporary bilateral relations has not ended with monuments. In 2015, Zinoviĭ Spechinskiĭ was invited again to Japan, where he repeated the symbolic handshake with the now retired Captain Tōgō Hiroshige. Three years later, Tōgō’s great-grandson reciprocated with a visit to St. Petersburg on May 9, the Victory Day of Russia’s Great Patriotic War (1941–45). During the main ceremony, the honorary consul of the Russian Federation in Japan, Tamura Fumihiko, granted the newly opened Museum of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 a copy of the uniform and sword of Admiral Tōgō.

Along with the growing sensitivity to the Russian casualties, the Japanese government and the JMSDF have not forgotten their closest ally—the United States and its navy. Apart from frequent joint exercises, officers of the United States Seventh Fleet are customarily invited to the Memorial Ship Mikasa. Even though the United States was not Japan’s ally in 1905 and its navy did not take part in the battle, the commander of the Seventh Fleet attends the annual commemoration ceremony onboard the ship as a guest of honor.108 Peculiarly, the United States Navy has begun recently to expropriate the memory of the Battle of Tsushima for its own needs. Headquartered at the U.S. Fleet Activities Yokosuka, about one kilometer from the Memorial Ship Mikasa, the Seventh Fleet has used the site to strengthen its ties with the JMSDF and the Japanese naval community as a whole. Invoking the memory of Admiral Nimitz and his support for the memorial ship, tens of sailors from the carrier Nimitz painted the aging battleship’s hull in August 2009 (Figure 15). Two days later, Rear Admiral John W. Miller, commander of Carrier Strike Group 11, presented Nobuyuki Masuda, president of the Mikasa Preservation Association, with a framed photomontage detailing the connection between Admiral Nimitz and Admiral Tōgō (Figure 16). Even more staggering is the fact that some units in the Fleet have used the ship for their own ceremonies thus bringing the notion of expropriation to the extreme.109

Figure 15. Sailors of the carrier Nimitz paint the Memorial Ship Mikasa.

Source: Wikipedia Common.

Figure 16. Sharing common legacy: The commander of Carrier Strike Group 11, the United States Seventh Fleet, presents the president of the Mikasa Preservation Association with a photomontage of Admirals Tōgō and Nimitz. Source: Wikipedia Common.

Despite this ostensible transnationalization of the commemoration, the above three sites emphasize domestic virtues under the guise of reconciliation. As such, they can be considered to be a part of a trend, put into motion by the government and followed by local organizations, of transforming the nation’s past militant image by stressing the humanitarian facets of its modern history.110 Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the commemoration of the Battle of Tsushima in Japan has reflected this novel amalgamation of narratives which has succeeded in attracting a new audience. In 2015, for example, as many as 253,000 guests visited the Memorial Ship Mikasa, and the Mikasa Preservation Society had 3,790 members.111

Concluding Remarks

Since 1905, the memory of the Battle of Tsushima in Japan has undergone several radical shifts. Each phase in the evolution of collective memory reflected changing attitudes toward war and militarism as well as the national identity and spirit present at the time. Currently, the battle is presented as a unique episode of self-defense, during which humanitarian acts abounded. If one disregards the expansionist and colonial background of the war and the carnage in the battle itself, the above features are largely correct. The battle was an act of self-defense and it ended with some humanitarian gestures. But one should not miss other undertones of the recent nostalgia, especially the longing for foreign backing and admiration. After all, the battle raged in an era of broad international support for Japan and its cause.112 In this sense, the Russo-Japanese War is arguably the only modern conflict that Japan can celebrate, memorialize, or remember without real or manufactured war guilt. In this spirit, the committee that stood behind the erection of another new monument in 2004 could suggest, in what seems to be implicitly against the current constitution, that “present-day Japan has lost its self-confidence.” Accordingly, national pride could be fostered by

handing on the inheritance of 27 May and engraving it in the hearts of the Japanese people. Only then will our country, Nippon, be able to recover its great hopes and dreams. Our committee continues to plead for a return to the old Japan and considers this an opportunity to reassert [the values of] ‘Bushidō JAPAN’, ‘genuine nationalism’, and the creation of a proud Japan as objectives for future generations.113

Indeed, the stream of books, films, conferences, and public ceremonies commemorating the war’s centenary anniversary during 2004–5 and afterward suggests that many contemporary Japanese yearn for this early-twentieth-century state of affairs. It was not merely a time when good old values ruled, in their view, but a brief period during which their country could display unfettered patriotism, project power, and even take hold of foreign territories in the Asian continent, while simultaneously being venerated internationally as a David fighting a Goliath. Japan later lost the benefit of this dualism. After the First World War, it was perceived by others as a menacing imperialist power, and since the end of the Second World War, under the restrictions of its new constitution, it has largely been seen as a benign but militarily weak state, dependent on others. Thus, the memory of the Battle of Tsushima in present-day Japan fulfills a potent role, reminding the Japanese that the being both strong and venerated is rare, but possible.

Acknowledgment. This article is a revised and largely expanded adaptation of some parts of Chapter 3 of my forthcoming book Tsushima (Oxford University Press, 2022). I thank Oxford University Press for generously agreeing to let me use the material here. I am grateful to Agawa Naoyuki, Inaba Chiharu, Bruce Menning, Alessio Patalano, Sven Saaler, J. Charles Schencking, Mark Selden, Ronald H. Spector, Hew Strachan, Subodhana Wijeyeratne, and several anonymous reviewers for reading early drafts of the specific materials appearing in this article, and for supplying invaluable leads and constructive criticism.

Notes

For an overview of the battle, see Julian S. Corbett, Maritime Operations in the Russo–Japanese War, 1904–5, 2 vols. (London, 1914; rep., Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994), 2:141–344; Rotem Kowner, Tsushima (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 40–82.

The Russian losses included 125,910 tons sunk, 48,941 tons captured, and 23,879 tons interned. The total figure includes 146,905 tons of warships and 51,916 tons of auxiliary ships. The Russian and Japanese aggregate displacements are calculated based on Rotem Kowner, Historical Dictionary of the Russo–Japanese War, 2nd ed. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), passim, and Hansgeorg Jentschura, Dieter Jung, and Peter Mickel, Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1977), 124.

For the commemoration of the war in post-1905 Japan, see Frederick R. Dickinson, “Commemorating the War in Post-Versailles Japan,” in John W. Steinberg et al. (eds), The Russo–Japanese War in Global Perspective, 2 vols. (Leiden: Brill, 2005–7), 1:523–43; Ben-Ami Shillony and Rotem Kowner, “The Memory and Significance of the Russo–Japanese War,” in Rotem Kowner (ed), Rethinking The Russo–Japanese War, 1904–05 (Folkestone, UK: Global Oriental, 2007), 1–9.

For the Japanese losses in the war, see Kowner, Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War, 100–1.

For these efforts, see Robert Valliant, “The Selling of Japan,” Monumenta Nipponica 29 (1974), 415–38; Rotem Kowner, “Becoming an Honorary Civilized Nation,” The Historian 64 (2001), 19–38.

Proverbs 24:17–18. For the selective reintroduction and at times also invention of the samurai code (Bushidō) in Meiji Japan, see Oleg Benesch, Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), especially 76–110.

For the poem, see Donald Keene, Emperor of Japan (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 645.

Interestingly, the news of the triumph in the Battle of Mukden prompted the gathering of twice as many people. See Sakurai Ryōju, Taishō seijishi no shuppatsu (Tokyo: Yamakawa Shuppansha, 1997), 22–5.

See, e.g., “Kaigun dai-shōri” (The navy’s great victory), Tōkyō Niroku Shimbun, 29 May 1905, 1; “Dai-kaisen” (The great naval battle), Hōchi Shimbun, 30 May 1905, 2.

Stewart Lone, Army, Empire, and Politics in Meiji Japan: The Three Careers of General Katsura Taro (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000), 117. Often forgotten, Russia too was broke and required loans. See William C. Fuller, Civil-Military Conflict in Imperial Russia, 1881-1914 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1985), 160.

Elting E. Morison, The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, 8 vols. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1951–54), 4:1221–2. Also see Komura Jutarō to General Kodama Gentarō, 9 June 1905, in Japan: Gaimushō, Nihon gaikō bunsho: Nichiro sensō, 5 vols. (Tokyo: Gaimushō, 1958-60), 5:252–4.

For the takeover of Sakhalin, see Hara Teruyuki (ed), Nichiro sensō to Saharin-tō (Sapporo: Hokkaido Daigaku Shuppansha, 2011(; and Marie Sevela, “Chaos versus Cruelty: Sakhalin as a Secondary Theater of Operations,” in Kowner (ed), Rethinking, 93–108.

See Rotem Kowner, “Japan’s ‘Fifteen Minutes of Glory’,” in Yulia Mikhailova and M. William Steele (eds), Japan and Russia: Three Centuries of Mutual Images (Folkestone, 2008), 47–70.

For a personal account of one of the prisoners, see Vladimir P. Kostenko, Na ‘Orle’ v Tsusime (Leningrad: Sudostroenie, 1955), 469–70; For the general treatment of Russian POWs during the conflict, see Rotem Kowner, “Imperial Japan and its POWs,” in Guy Podoler (ed.), War and Militarism in Modern Japan (Folkestone, 2009), especially 86–7.

Georges Blond, Admiral Togo (New York: Macmillan, 1960), 237. Also see Frank Thiess, The Voyage of the Forgotten Men (Tsushima) (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1937), 385.

The most notable artistic depiction of the visit was made by the Japanese painter Fujishima Takeji (1867–1943). The painting is available online here.

The other hospital ship, the Orël, remained in Japan as a prize. For the negotiations and debate about these ships, see Pierre Boissier, From Solferino to Tsushima: History of the International Committee of the Red Cross (Geneva: Henry Dunant Institute, 1985), 331–2; House of Representatives, Papers Relating to Foreign Relation of the United States, vol. 1: House Documents (Washington: GPO, 1906), 1: 595–6, 790–1.

There is extensive literature on the Portsmouth Peace Conference and its repercussions. E.g., Eugene Trani, The Treaty of Portsmouth (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1969); Shumpei Okamoto, The Japanese Oligarchy and the Russo–Japanese War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1970), 150–63; Norman Saul, “The Kittery Peace,” in Steinberg et al. (eds), The Russo–Japanese War, 1:485–507; Steven Ericson and Allen Hockley (eds), The Treaty of Portsmouth and Its Legacies (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2008); and Francis Wcislo, Tales of Imperial Russia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 204–14.

Vladimir Semenov, The Price of Blood; The Sequel to “Rasplata” and “The battle of Tsushima,” (London: J. Murray; New York: E.P. Dutton, 1910), 82.

Okamoto, The Japanese Oligarchy, 196–223; idem, “The Emperor and the Crowd,” in Tetsuo Najita and J. Victor Koschmann (eds), Conflict in Modern Japanese History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 262–70; Lone, Army, Empire, 117–20.

For an overview of the war’s impact on Japan, see Rotem Kowner, “The War as a Turning Point in Modern Japanese History,” in R. Kowner (ed), The Impact of the Russo–Japanese War (London: Routledge, 2007), 29–46.

Schencking, J. Charles. Making Waves: Politics, Propaganda, and the Emergence of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1868–1922 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005), 111.

See Ian Nish, Anglo-Japanese Alliance: The Diplomacy of Two Island Empires 1984-1907 (London: Athlone Press, 1968).

See, e.g., Jiji shimpō, 21 October 1905; “Editorial,” The Yamato Shimbun no. 1870, 13 November 1905, 1. For the atmosphere among the British naval observers in Japan that helped elicit the association between and Nelson, see Richard Dunley, “‘The Warrior Has Always Shewed Himself Greater Than His Weapons’: The Royal Navy’s Interpretation of the Russo-Japanese War 1904–5,” War & Society 34 (2015) 248–62.

For the naval review, see Takashi Fujitani, Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 134–6; Blond, Admiral Togo, 240–2.

There have been sundry speculations and theories about the source of the explosion, ranging from humid gunpowder to a terrorist attack. See Toyoda Jō, Kikan Mikasa no shōgai (Tokyo: Kōjinsha, 2016), 368–402.

Constantine Pleshakov, The Tsar’s Last Armada: The Epic Voyage to the Battle of Tsushima (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 316.

Lithograph, 1905. Dimensions: 40×55 centimeters. Among the other dignitaries (standing to the Emperor’s left): Admiral Gerard Noel, Commander-in-Chief, China Station; Admiral Itō Sukeyuki; Admiral Yamamoto Gonnohyōe; Prime Minister General Katsura Tarō; and Field Marshal Yamagata Aritomo.

The aggregate displacement of the Russian ships captured at the Battle of Tsushima was 48,941 tons (among them 32, 641 tons of warships). The IJN had also captured five semi-sunken Russian battleships in Port Arthur which were commissioned after the war. For the Imperial Russian Navy’s (IRN) structure and vessels in 1906, see The Editors, “The Progress of Navies,” 23–5. Cf. “Sea Strength of the Naval Powers,” Scientific American 93, no. 2 (July 8, 1905), 26.

See David C. Evans and Mark R. Peattie. Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997), 147. This specific position is also corroborated by George Modelsky and William R. Thompson, Seapower in Global Politics, 1494–1993 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988), 123, although their proportional distribution of global sea power suggested that the IJN had never been in a higher position than the sixth place.

For the popularity of cards containing naval images, primarily warships, both during and after the Russo–Japanese War, see Japanese Philately 41:4 (August 1986), 152–8.

By the same token, the Army Day was celebrated every year on 10 March, the date of the victory in the 1905 land Battle of Mukden. For the emergence of these two dates, see Harada Keiichi, “Irei to tsuito: sensō kinenbi kara shūsen kinenbi e,” in Kurasawa Aiko et al. (eds), Sensō no seijigaku (Tokyo: Iwanami, 2005), 296–307.

For the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and IJN’s respective resentment over the public indifference towards the army and navy memorial days, see Harada, “Irei to tsuito,” 300.

See Yuriĭ Pestushko and Yaroslav A. Shulatov, “Russo–Japanese Relations from 1905 to 1916: from Enemies to Allies,” in Dmitry V. Streltsov and Nobuo Shimotomai (eds), A History of Russo–Japanese Relations: Over Two Centuries of Cooperation and Competition (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 109.

For various indications of the flagging interest by 1906, see Isao Chiba, “Shifting Contours of Memory and History,” in Steinberg et al. (eds.), The Russo–Japanese War, 2: 361.

Today, this Memorial of the Battle of the Sea of Japan (Jpn. Nihonkai kaisen kinenhi) is part of Tonosaki park (Tonosaki Kokutei Kōen), in Kamitsushima town.

The other War God was the IJA’s Major Tachibana Shūta, who was killed in the Battle of Liaoyang. For more on Hirose, see Naoko Shimazu, Japanese Society at War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 197–229.

See Edwin Falk, Togo and the Rise of Japanese Sea Power (New York: Longmans, Green, 1936), 431–33; Jonathan Clements, Admiral Togo: Nelson of the East (London: Haus Publishing, 2010), 208–24.

Tōgō is accompanied by Major General Thomas Henry Barry, the superintendent of the United States Military Academy, West Point.

For the most part, Tōgō opposed the erection of statues of himself. Nonetheless, in 1927 he was persuaded to allow the erection of such a statue, alongside Nogi’s statue, at the Tōgō Park (Tōgō Kōen), on the grounds of Chichibu Ontake Shrine, near Chichibu, Saitama, and took part in the unveiling ceremony. See Ōkuma Asajirō, Shinsui Horiuchi Bunjirō shōgun o itamu (Fukuoka: Ōkuma Asajirō, 1942), 5.

At an earlier point in time, Ogasawara was heavily involved with the creation of the IJN myth of its first gunshin, Hirose Takeo. See Shimazu, Japanese Society at War, 200–2.

Upon Tōgō’s death, his domestic lionization reached a zenith alongside renewed international interest, as is evidenced by a flurry of publications in Japanese and English. See, for example, Nakamura Koya, Sekai no Tōgō gensui (Tokyo: Tōgō Gensui Hensankai, 1934); Abe Shinzō, Tōgō gensui jikiwashū (Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 1935); Kaigun Heigakkō, Tōgō gensui keikōroku (Tokyo: Dai-Nihon Tosho, 1935); Naganari Ogasawara. Life of Admiral Togo, trans. by Jukichi and Tozo Inouye (Tokyo: Seito Shorin Press, 1934); Ronald Bodley, Admiral Togo (London: Jarrolds, 1935); Falk, Togo (1936); and Koya Nakamura, Admiral Togo (Tokyo: Togo Gensui Publishing Society, 1937).

A key figure in the campaign was Shiba Sometarō, the editor of The Japan Times during the 1920s. See his “Save the Mikasa,” The Japan Times, 14 June 1923; “Save the Mikasa!” The Japan Times, 21 July 1923.

For the establishment of the Society (Jpn. Mikasa Hozonkai), see “‘Save the Mikasa’ Men Meeting to Organize Today,” the Japan Times, 24 March 1924; Ogasawara Naganari, Seishō Tōgō Heihachirō den (Tokyo: Kaizōsha, 1934), 490–6.

Ozaki Chikara, Seishō Tōgō to reikan Mikasa (Tokyo: Mikasa Hozonkai, 1935), 100–1. For the Society and its publications, see Ministry of Defense, National Institute for Defense Studies (NIDS), Tokyo, Senshi–Nichiro sensō-11.

Edan Corkill, “How the Japan Times Saved a Foundering Battleship, Twice,” The Japan Times, 18 December 2011.

Tatsushi Hirano et al., “Recent Developments in the Representation of National Memory and Local Identities,” Japanstudien 20 (2009), 252.

For this revived memory, see Chiba, “Shifting Contours,” 2:365; Benesch, Inventing the Way of the Samurai, 178–80.

See Saburo Ienaga, “Glorification of War in Japanese Education,” International Security 18, no. 3 (1993–94), 119–20.

This Japanese traditional unit is now standardized as 30.3 centimeters. Thus, the measures of the monument are 11.51; 1.52; and 8.18 meters.

This phrase, as represented by the famous Z flag Tōgō hoisted on the Mikasa, is redolent of Nelson’s famous signal sent as the Battle of Trafalgar was about to commence: “England expects that every man will do his duty.”

“Togo shrine dedicated,” Nippu Jiji, 27th May 1940, 1. Curiously, and for a short time before the war, Tōgō worship took place also on American soil, as part of the Daijingu Temple of Hawaii, a Shinto shrine in Honolulu. See Wilburn Hansen, “Examining Prewar Tôgô Worship in Hawaii,” Nova Religio 14 (2010), 67–92.

For the history of the two shrines, see Nogi jinja-Tōgō jinja (Tokyo: Shinjinbutsu Ōraisha, 1993). In November 1945, however, the construction of a Buddhist temple of the Nichiren sect named Tōgōji was completed on the site of Tōgō’s villa in Fuchu, Tokyo Metropolis. Designed by the famous architect Itō Chūta it is considered today a major tourist attraction.

Hiroyuki Agawa, The Reluctant Admiral: Yamamoto and the Imperial Navy (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1979), 2.

Samuel Eliot Morrison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 3: The Rising Sun in the Pacific, 1931–April 1942 (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1948), 93.

Donald Goldstein and Katherine Dillon (eds.). The Pearl Harbor Papers: Inside the Japanese Plans (Washington, DC: Brasseyʾs, 1999), 122.

For the reasons behind the choice of that day for departure, see Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully. Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway (Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, 2005), 69.

For the state of the site during the early years of the occupation, see Elmer Potter, Nimitz (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1976), 397–8, 466.

For this notion, see Alessio Patalano, Post-war Japan as a Sea Power: Imperial Legacy, Wartime Experience and the Making of a Navy (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 37.

For Itō’s campaign, see Alessio Patalano, “A Symbol of Tradition and Modernity,” Japanese Studies 34 (2014): 61–82.

See Potter, Nimitz, 56–7, 158, 397–8, 467; and Brayton Harris, Admiral Nimitz (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 13, 48, 175.

Directed by Watanabe Kunio, the film offered a pioneering portrayal of Emperor Meiji. See Chiba, “Shifting Contours,” 2:371–4.

For the reception of the film, see Joseph L. Anderson and Donald Richie, The Japanese Film: Art and Industry (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), pp. 250–52.

“Japan Deeply Moved By War Film,” The Times, 29 May 1957, 3, quoted in Benesch, Inventing, 219–20. For the early decades of Japan’s dialectical dealing with its imperial past, see Sebastian Conrad, “The Dialectics of Remembrance: Memories of Empire in Cold War Japan.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 56 (2014), 9–25.

Bungei Shunjū had been involved in drumming up public interest in the Memorial Ship Mikasa since 1957. See NIDS, Senshi–Nichiro sensō-7. For Nimitz’s article in the Bungei Shunjū, see Potter, Nimitz, 466–7; Harris, Admiral Nimitz, 210. Nimitz’s legacy did not end there. In 2009, sailors from the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz volunteered to paint the Mikasa. For further information on Nimitz’s involvement in the Mikasa restoration, see Papers of Chester W. Nimitz, Archives Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, D.C., Box 63, folders 499-503.

The main source on the restoration project is the 32-page booklet published by the Mikasa Preservation Society, Memorial Ship Mikasa (Yokosuka, Japan: Mikasa Preservation Society, 1981).

After an initial surge of visitors, their number fluctuated between 150,000 and 200,000 annually throughout the 1970s and the 1980s, but declined considerably in the following decade. See Tatsushi Hirano, Sven Saaler, and Stefan Säbel, “Recent Developments in The Representation of National Memory and Local Identities: The Politics of Memory in Tsushima, Matsuyama, And Maizuru.” Japanstudien 20 (2009), 252.

Elmer B. Potter and Chester Nimitz (eds.), The Great Sea War (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1960); Chester Nimitz and Elmer B. Potter, Nimittsu no taiheiyō no kaisen-shi (Tokyo: Kōbunsha, 1962).

For Nimitz’s donation of the royalties of the Japanese translation of his book, see Potter, Nimitz, 467; and Harris, Admiral Nimitz, 175.

Another Tōgō Shrine alongside a small museum was opened on 27 May 1971 in the town of Fukutsu, in the vicinity of the 1934 memorial monument.

Harald Salomon, “Japan’s Longest Days,” in King-fai Tam et al. Chinese and Japanese Films on the Second World War (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2015), 126.

Salomon, “Japan’s Longest Days,” 121; Marie Thorsten and Geoffrey M. White, “Binational Pearl Harbor?” The Asia-Pacific Journal 8 (2010), Issue 52 no. 2.

The story was simultaneously reprinted in six volumes. See Shiba Ryōtarō, Saka no ue no kumo (Tokyo: Bungei Shunjū, 1969–72). A four-volume English translation of the novel has also been published recently, with the last of these being largely devoted to the battle. See Ryōtarō Shiba, Clouds above the Hill (London: Bungei Shunjū, 2012–14).

For Shiba’s literary legacy and its impact on Japan’s war memory, see Donald Keene, Five Modern Japanese Novelists (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 85–100; and Hidehiro Nakao, “The Legacy of Shiba Ryotaro,” in Roy Starrs (ed.), Japanese Cultural Nationalism at Home and in the Asia Pacific (Folkestone, England: Global Oriental, 2004), 99–115.

For Shiba’s historical perspective, see Tomoko Aoyama, “Japanese Literary Response to the Russo–Japanese War,” In David Wells and Sandra Wilson (eds), The Russo–Japanese War in Cultural Perspective, 1904–05 (Houndsmills, UK: Macmillan, 1999), 79–82; Sinh Vinh, “Shiba Ryōtarō and the Revival of Meiji Values,” in James C. Baxter (ed.), Historical Consciousness, Historiography, and Modern Japanese Values (Kyoto: International Research Center for Japanese Studies, 2006), pp. 143–51; and Alexander Bukh, “Historical Memory and Shiba Ryōtarō,” in Sven Saaler and Wolfgang Schwentker (eds.), The Power of Memory in Modern Japan (Folkestone, UK: Global Oriental, 2008), 96–115.

See Nomura Naokuni, Gensui Tōgō Heihachirō (Tokyo: Bungei Shunjū, 1968); Yonezawa Fujiyoshi, Tōgō Heihachirō (Tokyo: Shin Jinbutsu Ōraisha, 1972); and Togawa Yukio, Nogi to Tōgō (Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten, 1972).

Yoshimura Akira, Umi no shigeki (Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 1972). The book was reissued in several editions and numerous reprints, most recently in 2003.

This serialized manga was also published in book form. See Ueda Shin and Takanuki Nobuhito, Jitsuroku Nihonkai kaisen (Tokyo: Tachikaze Shobō, 2000).

Egawa Tatsuya, Nichiro sensō monogatari (Tokyo: Shōgakukan, 2001–6). Starting in 2001, the story was serialized in a leading manga weekly for five years and then reissued gradually in 22 independent volumes.

For the differences between Egawa and Shiba’s works, see Yukiko Kitamura, “Serial War: Egawa Tatsuya’s Tale of the Russo–Japanese War,” in John W. Steinberg et al. (eds.), The Russo–Japanese War, 2: 427–30.

For a brief review of the attitude toward the war and empire in 1990s Japan, see Conrad, “The Dialectics of Remembrance,” 25–31.

Hirose Takeo, “Nichiro sensō o megutte,” in Roshiashi Kenkyūkai (ed.), Nichiro 200 nen—rinkoku Roshia to no Kōryūshi (Tokyo: Sairyūsha, 1993), 106.

See Toyoda Jō, “Tōgō Heihachirō,” in Bungei Shunjū (ed.), Nihon no ronten (Tokyo: Bungei Shunjū, 1992), 594–601; and Ienaga, “Glorification of War,” 129–31.

For an overview of these textbooks, see Elena Kolesova and Ryota Nishino, “Talking Past Each Other?” Aoyama Journal of International Studies 2 (2015), 22–3.

The presumed link with these two foreign warships has also been maintained on the Memorial Ship Mikasa’s webpage. They are “the world’s three largest memorial ships,” the webpage text states, “because they bravely fought in historic naval battles to protect their respective nation’s independence.” Available online here (accessed on 1 March 2020).

For this monument and the “pacifist” aspects of the battle’s recent commemoration, see Hirano et al., “Recent Developments,” 253–7.

For photos of this site and the cenotaph in its center, see Trip Advisor (accessed on April 19, 2022).

The original drawing used in the relief is printed in H.W. Wilson, Japan’s Fight for Freedom, 3 vols. (London: The Amalgamated Press, 1904–06), 3: 1385.

In July 2009, for example, a ceremony of reenlisting a crewmember took place onboard the memorial ship. See Wikipedia Commons.