Abstract: This paper, as a conclusion to this special issue, discusses approaches taken to memory studies of the First World War and what they can tell us about commemoration of the Asia-Pacific War. A lot of work remains to be done in connecting the historiographies of the two world wars of the twentieth century, but this is important if we are to fully understand the development of war and memory throughout the twentieth century and beyond. The First World War was an important reference point for those who fought in the second and founded practices of commemoration such as the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Based on my experience as a First World War historian, I address some of the important themes that this special issue on the Asia-Pacific War has raised, namely the image of the soldier, commemoration, the temporal memory of war and how an expanded geographic lens has altered our understanding of the Second World War in general.

Keywords: commemoration, Asia-Pacific War, First World War, mourning, war and memory, global war

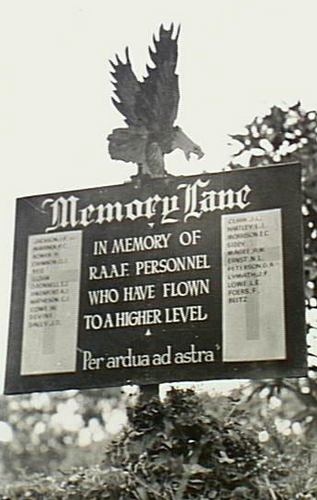

Figure 1: Port Moresby, New Guinea, Sign Erected by the RAAF ToC H Group in Port Moresby to commemorate those killed. (Australian War Memorial, P02704.026)

Introduction

As a First World War historian who completed his PhD in 2014, my research became invariably interconnected with the centenary of the outbreak of the conflict and has been ever since affected by the way the war is remembered publicly. Indeed, my home country, Ireland, is still celebrating its “decade of centenaries” which is due to end in 2023 as we commemorate the entwined memories of 1914, the beginning of Irish independence and civil war which ended in 1923. The centenary commemorations of the First World War demonstrated a desire among historians to encourage the general public to think beyond familiar historical narratives, and it is likely that the centenary of the Second World War will take a similar approach. However, historians can be accused of having a narrow focus and there is still a notable lack of crossover studies that engage with the two major global conflicts of the twentieth century. In a recent contribution to this historiographical debate, Catriona Pennell and Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses argue that historians have been slow to acknowledge or appreciate the commonalities and scope for useful cross-referencing between the two world wars (2019, 4).

This special issue on Re-Examining Asia-Pacific War Memories focused on the notion of post-memory and war, and serving as a conclusion this paper turns to a broader view of commemoration and war memory in general and its development since the end of the First World War. This will connect to the themes of this special issue and widen the temporal and geographic frame of our discussion on war memory. While it will necessarily entail some repetition it aims to provide some links and comparisons. It will look at the image of the fallen soldier, different modes of mourning, the temporal memory of war and geographical expansion of remembrance. This relates to the pioneering work of Pierre Nora and the notion of the “age of commemoration” which focus on two concepts—the acceleration and democratization of history (2002, 4-5). The democratization of history in Nora’s view was especially important for opening up the memory of war and de-centering the dominant narratives into the extra-European world.

Historians, by nature of their profession, engage in a collective dialogue with the past. Reflections on the First World War at various stages of its commemoration have brought in differing contemporary factors (Horne 2014, 635). This is notable in the rediscovery of the connections between war and the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 as we try to make sense of the current Covid-19 crisis. The seventy-fifth anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War saw the publication of such pioneering works on the history of memory such as George Mosse’s Fallen Soldiers (1990). With this in mind, this special issue has sought to break new ground on the seventy-fifth anniversary of the end of the Asia-Pacific War; by engaging with developments in memory studies and applying them to underrepresented battlegrounds and sites of commemoration in the overall Second World War historiography. This work is of course built on the foundations laid by those that have come before us. In the first decade of the twenty-first century scholars focused on the memory of the conflict, innovating approaches and adapting existing historiographical debates, notably Nora’s work on memory and commemoration in France (Saaler and Schwentker 2008). In 2001, Fujitani, White, and Yoneyama lamented the fact that the Asia-Pacific War was largely over-shadowed by interest in the war in Europe and the Holocaust, in particular among Anglophone audiences (2001, 3). Thanks to their contribution and those of others we can safely say that the Asia-Pacific is now much less seen as a sideshow to the Second World War, but has entered the mainstream of memory studies.

The end of the Second World War is an important breaking point in the global history of the last century, credited with helping to spark decolonization and the Cold War. In the case of Europe, however, a first significant break in twentieth century cultural history came in 1918, not 1945. Once the Great War ended, Jay Winter (2017, 206) argues, its remembrance in Europe entailed a return to traditional practices of mourning, embedded in classical, romantic, and religious images and languages. How does this work when we focus our lens on the memory of war in the Asia-Pacific and in particular when looking at the war memories of those who were not part of a European imperial metropole, a dominion nation or the USA?

The Image of the Soldier

Perhaps it is a contradiction in terms but the outbreak of total war in 1914 changed the presentation of war from representing war to representing “warriors” (Winter 2017, 3). Even those who gloried in the new notion of mechanized warfare, as recorded in Ernst Jünger’s war memoir In Stahlgewittern (1920), still held the individual experience as central to the narrative of war. Indeed, it was the overwhelming development of military technology that led some to rescue the image of the individual soldier from warfare that had become depersonalized. The myth of T.E. Lawrence, known commonly as Lawrence of Arabia, proved popular in post-war Britain as it seemed to show that one person’s decisions could still have a dramatic impact in modern war (Faulkner 2017). Jünger aside, the search for individual war heroes meant looking to extra-European battlefields of the war or “sideshows” such as the Middle East where mechanization was supposedly not as developed as on the Western Front. As Stefan Goebels (2007, 202) shows, tales of chivalry dominated British war commemorations, this rendered the unrelenting slaughter of the Great War into a narrative which was intelligible to Britons, a supposedly unmilitary nation which was not prepared to “elevate military virtues to social norms of national life.”

While Jünger and others may have celebrated war, this shift to the individual experience opened up the possibility for many other soldier/memoirists to portray themselves as victims of war regardless of whether they were on the winning side or not. This can be clearly seen in cases of the internment of “enemy” civilians both male and female who were simply guilty of being of the wrong nationality and in the wrong place (Stibbe 2020, 39). Representing war came to mean representing the civilian victims of war and genocide. The global experience of the First World War also created global memories of the war. For example, although overlooked in many discussions of the First World War and memory, demobilized African soldiers and members of the various carrier corps returned to their hometowns with their own experiences of the various battlefields and their own commemoration practices (Moyd 2011). Integrating these individual experiences from the various battlefields of conflict into the narrative of the war as a whole restores agency not only to such forgotten soldiers but also to non-combatant communities at war and creates a more substantial historical understanding of the war. These are themes that certainly reappear in discussions of memory of the Second World War. Both wars had disastrous effects on local communities away from the main battlefields in areas such as sub-Saharan Africa as men were recruited into carrier corps, taken away from their homes and returned after the war traumatized. Bringing in the voices of other victims/belligerents of the war also serves an important function of de-centering the history of the Asia-Pacific War from the dominance of the major Allies and the Japanese.

Mourning and Commemoration

In their ground-breaking work on war and memory Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau and Annette Becker described how the huge battlefield losses on the Western Front in the First World War had radically altered pre-war European attitudes to death and mourning (Audoin-Rouzeau and Becker 2002, 179). During the war mourning became a repressed theme and was so pervasively denied as to become almost socially invisible). In France, the terrible slaughter on the Western Front caused a major breakdown in funeral and mourning etiquette. During the war itself ostentatious displays of mourning, such as widows wearing black dresses, seemed increasingly inappropriate as the mass slaughter continued. This was a decisive shifting point in the relationship of Westerners to death. The grief people felt for the men who died over a hundred years ago has left perceptible traces today and this is perhaps truer for those who were killed during the Second World War.

Inter-war generations failed to see how much the culture of violence permeated their lives and how they were irreversibly changed by its brutalization, and most importantly, how this contributed to them embarking into the abyss once again in 1939 (Audoin-Rouzeau and Becker 2002, 227). In this vein, Akiko Takenaka perceives a similar phenomenon in Japan during the Asia-Pacific War as the cult of sacrifice for the nation made the notion of mourning the dead increasingly unacceptable (2015). This taboo on mourning operated through a different dynamic, however, it was not from a social fatigue with death but through censorship and indoctrination as families were pushed by the state to feel joy rather than despair at the loss of a loved one in battle. The conduct of total warfare necessarily entailed an institutionalization of grief, which in Japan focused around communal activities at Yasukuni shrine with the state trying to find an “exalted meaning for a war death” (Takenaka 2015, 95).

Despite the attempt to seek out heroes to memorialize, collective commemoration remained the main method of national memory, especially in Japan where Yasukuni honors the fallen not just from the Pacific War but across all of Japan’s imperial wars, where the soldier is not glorified as an individual but as part of a great whole. Since the Russo-Japanese War there was increasingly less space for private mourning in Japan (Hettling and Schölz 2019). Collective commemoration could also take the form of giving the war hero anonymity. In 1959 Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery was designated to house the remains of the many unknown Japanese soldiers who died during the Second World War. It even appeared, as discussed in this special issue by Daniel Milne and David Moreton, at Ryōzen Kannon in Kyoto.

A tomb dedicated to the unknown soldier was an innovation in war memory directly resulting from the First World War, and it soon became a standard practice in commemorative activities worldwide. They were proposed while the war was ongoing and then institutionalized in France and Britain on armistice day 1920 with the first interments taking place the following year at the Arc de Triomphe and Westminster Abbey in Paris and London respectively. The effect of modern munitions on the human body often meant that identification of remains was impossible and the scale of slaughter dwarfed the individual experience. The tomb of the unknown soldier allowed the anonymous masses to enter public memory and take the place of the named hero and thus provided a means to come to terms with the trauma of war (Kramer 2007, 284). Through the tomb to the unknown soldier, we see an attempt to collectivize individual mourning around what Mosse termed “the cult of the fallen soldier” (1990, 70). The tomb also helped to distract the public from the fact that the nation-state had sent more people into death than it could administer. One could see it as an acknowledgment that the state was incapable of commemorating the dead on an individual level, while at the same time masking this fact as “the” unknown soldier was one individual.

Beatrice Trefalt’s paper in this issue discussed another important aspect of the memory of war, the performative function of re-enactment in stimulating and maintaining memory. In going to locate and retrieve the remains of those left behind, the Japanese veterans of the 18th Army also necessarily retraced their footprints during the New Guinea campaign. This trip of retrieval was described as a mission and took an air of military campaign as the veterans once again battled the tropical heat and the difficult terrain to access old battlefields. In this sense, we see a difference with Mosse’s discussion on commemoration in the act of visiting the carefully manicured war graves on the Western Front (1990, 107-156). In the replay of the battle against nature in New Guinea described by Trefalt, it is not the beauty of nature that serves as a catharsis but facing again a challenging situation, and thus in a manner re-enacting the war time experience, that helps the veterans to find some solace.

The Temporal Memory of War

A common theme when looking at the memory of the First World War is how the pre-war period interplays with memory of the war. The pre-war period is perhaps trickier to isolate in the Asia-Pacific theater as one conflict became entangled with another arguably from 1931 onwards. The pre-war period is forgotten to a certain extent because the conflict, especially if we take 1931 as the starting point, had such a long duration. When one looks at the First World War, most reflections of that war are predicated on its beginnings. Of course, this may have more to do with how much more ink has been spilled in debating the origins of the First World War than with that of the second. However, it is also perhaps connected with the levels of violence that were sustained between the two wars. This is not to deny that pre-1914 the world was a peaceful place, far from it. While current historiography increasingly discusses the long First World War as to be dated from 1911 to 1923, the overriding popular image of the First World War in Western Europe is framed around a loss of innocence during the summer of 1914. This is presented in familiar imagery such as the “pals” signing up together in Oxford or the German school students pressured by their teachers to do their patriotic duty, famously depicted in All Quiet on the Western Front.

Japan’s intervention in Siberia in 1918 (intended as a new front of the First World War) offered some narratives that are familiar. The Siberian Intervention was a war in which the Japanese Empire first experienced defeat. The Japanese army “withdrew” from Siberia in 1922, but their mission was incomplete: the Bolsheviks defeated all foreign intervention troops and counter-revolutionary forces and gained control of the entire territory of the former Russian Empire. Defeat in the battle of Yufta in 1919 and at Nikolayevsk in 1920 is seen as the pivotal battle that eventually forced Japan’s hand to withdraw from Siberia in 1922 (Izao 2017, 171). Japanese soldiers, many of them disillusioned with the war, were repatriated in October 1922 to find that the intervention was also deeply unpopular with the public. Survivors of the battle of Yufta labored hard to have a stone monument erected at Yasukuni in memory of their fallen and almost forgotten comrades—the memorial to the Tanaka Brigade (Tanaka-shitai), which still stands in the shrine today. Ironically the soldiers’ return to Japan almost coincided with the Peace Commemorative Exposition at Ueno Park, Tokyo held four months previously. This meant that the commemoration of the First World War in Japan took place essentially while Japanese soldiers were still fighting it. The Siberian Intervention, however, remains a largely forgotten episode in the history of warfare and Japan, overshadowed by the narrative of Russia’s internment of Japanese soldiers in Siberia in the post-Second World War years.

In the case of Japan, defeat looms largest in memory and signifies the breaking point between pre- and post-war. To a certain extent the Asia-Pacific war itself forms part of the pre-war narrative and disentangling it from a period of peace is a difficult undertaking (Dower 2000, 45). Through what John Horne (2008, 24) termed the “galvanizing effect”, confronting the rupture of defeat forces a society to address the past in ways the victor can avoid. This may mean self-consciously drawing on the past or appealing to a new future or more often doing both simultaneously.

In drawing on the narrative of the Asia-Pacific War for Japan, there were no “guns of August” as in Europe in 1914 to signify a breaking point of peace and the beginnings of conflict. This causes problems for us in our attempts to commemorate the war. What starting dates and what conflicts do we include in the Asia-Pacific War and can we really divorce the Pacific War (as it is generally understood in Anglophone literature) from the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), or what we should term the global Second World War? Paul D. Barclay’s recent article in the Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus makes a convincing argument for the concept of Japan’s “forever war” lasting from 1895-1945 which shows that Japan fought several particular wars that overlapped with one another to produce cumulative effects (2021, 24). Collin Rusneac’s study of Sanadayama cemetery in Osaka in this special issue showed us a direct link between Japan’s previous imperial conflicts and the Second World War. This special issue has also shown that we can project this forward beyond 1945 and see how memory and commemoration of the Asia-Pacific War became intertwined with decolonizing or Cold War narratives as shown in Milne and Moreton’s analysis of Ryōzen Kannon and Arnel Joven’s study of Camp O’Donnell. It is important that we keep these local experiences intertwined with the conflict as a global whole.

Geographical Memory of Twentieth Century Warfare

Following on from a temporal consideration it is now perhaps fitting to turn to the geographic. As in the First World War, during the Asia-Pacific War, imperial interaction was at the heart of the conflict. These were wars envisioned in transnational terms even if they were fought for national needs. For imperialists, total war has the unfortunate side-effect of turning the colonial order upside down. In the First World War, the extension of the fighting into Africa and the use of colonial troops on the western fronts sparked uneasy debates in the imperial metropoles of Britain and France. In the colonial sphere, the Allied takeover of Germany’s African colonies in what are now Togo, Cameroon, Tanzania and Namibia, was delicately managed for fear of upsetting colonial power balances.

A link we can make to literary representations of the Asia-Pacific War and its memory and that of the First World War is the image of conflict in the colonies and the colonial landscape of the war zones described. This expectation of what fighting in the supposed under-developed parts of the world would be like fit into what Robert Gerwarth and Stephan Malinowski (2009) described as the “colonial archive”. The battle zones of New Guinea, as discussed in this special issue, fit what Susan Zantop described as ‘colonial fantasies’ in reference to nineteenth century German colonial projects. Japan’s imperial expansion on the level of cultural and discursive history somewhat fits into this framework. The “unconsciously expressed colonial fantasies” which are the cause of the desire for imperial expansion are also replayed in soldiers’ memoirs of the war (Zantop 1997, 9). While Zantop’s thoughts focused on Africa and Germany’s Eastern neighbors, as with late nineteenth century Germany, the vision of Japan as a nation was in many ways created at the colonial periphery, where the “civilizing mission” interacted with racial stereotypes, sexuality and gender roles (Conrad 2014, 18).

One of the abiding memories of the First World War in Germany made effective use of the colonial archive. This was the celebration of the supposed heroics of Paul Von Lettow-Vorbeck’s troops who had kept the British Army occupied in East Africa throughout the conflict. They were the last German forces to surrender, only upon hearing about their homeland’s capitulation on 25 November 1918, two weeks after the armistice in Europe. Lettow-Vorbeck and his East African troops paraded through the Brandenburg Gate on their return to Berlin declaring themselves “undefeated in the field”. However, this was a very different field to that of the western front, von Lettow-Vorbeck’s troops fought a supposedly heroic fight against nature, climate and an overwhelmingly powerful foe (Leonhard 2018, 350). Lord Cranworth, who had experience fighting in France and East Africa noted the difference between ‘civilized’ and ‘uncivilized” battlefronts: “I would sooner hear a big shell traveling along like an express train, than hear a lion roar a few yards away from me. I have heard both very often, but a shell never made my flesh run up my spine until it turned my hair into pin wire” (Samson 2013, 155).

Similarly, Japan’s actions in New Guinea during the Asia-Pacific War were remembered primarily as a war against the terrain and tropical diseases, not the enemy, as Ogawa Masatsugu’s memoirs, discussed in Nishino Ryota’s contribution to this special issue, make clear. The battlefields of New Guinea could serve as a contrast to the war in China. Here warfare had not taken on its totalizing and brutal nature but retained aspects of a colonial fantasy of adventure. Unlike Lettow-Vorbeck, however, Ogawa and his comrades did not receive a hero’s welcome on return from the war.

In addition, descriptions of the local New Guineans as welcoming and performing a narrative role of “noble savage” in memoirs are presented in Nishino’s paper in this special issue. The myth of the “noble savage” saw a revival in the early-twentieth century in the build-up to the First World War and the fear of anarchist terror and socialist/communist revolution (Ellingson 2001, 384). This welcome laid out to Japanese soldiers reflects this narrative and suggests a determination by the author to not just present the locals in a friendly light but as a comment on Japan’s suitability to run colonies in Asia and the Pacific. Ogawa’s encounters with the local population reflect that the war did not “extinguish images of the exotic savage” but multiplied the images of the indigenous people who were presented as servant, victim, pupil, ally and much less frequently, brother human (Lindstrom 2001, 122).

In the inter-war period in Germany (a country that like Japan had lost its empire after defeat in World War I) the image of the loyal Askari in German Africa served to prop up the notion that Germany was a modern “civilized” country fit to own an empire (Lewerenz 2010, 175). Of course, this image of the loyal Askari would be offset by the use of stereotypical imagery of barbarous violence deployed by French African troops on the Western Front and into the post war era with “Black Watch on the Rhine” propaganda related to alleged sexual violence and miscegenation during the French occupation of the Rhineland. Nevertheless, in 1916 an argument was made in one of Germany’s leading newspapers that the small German garrison in Samoa only surrendered to New Zealand forces to prevent any harm coming to the local population who were all loyal to Kaiser Wilhelm II (Kölner Zeitung 15 August 1916). This signals the beginnings of the “undefeated in the field” myth popularized in Germany in the interwar years. With the Armistice 11 November the German army could erroneously claim to having been undefeated and it was the socialist (implying Jewish) politicians in Berlin who had stabbed the army in the back (Schivelbusch 2003, 205-206). Indeed, looking to the supposed “sideshows” of the war the above-mentioned surrender of Lettow-Vorbeck with his army of Askari in East Africa provided an example of a “noble defeat” of the German army without an accompanying political deceit. With regard to the Asia-Pacific War, New Guinean carriers hired by the Allied Forces also fit this mold in Australian war memory of ‘mateship’ in which the loyal “native” whose fealty to the Imperial Power (a mandatory power in this case) justifies a territory’s colonial exploitation.1

By looking at the cases of German East Africa during the First World War and New Guinea during the Second, we can see an overriding theme of empire and war and the search to find a war narrative that fit a romantic, chivalric image of that was wiped out by modern innovations in war. Much as German and British soldiers engaged in war in Africa could claim (mistakenly of course) to speak of a war with honor contrast to the barbarity of the Western Front, so could Japanese soldiers remember the war in New Guinea as a more noble affair that could be discussed with more candor than in reminiscing on the China theater.

Indeed, memory of war is not necessarily tied to the memory of actual combat experience. As military and cultural history have become increasingly intertwined, attention to Homefront experiences and cultural demobilization have greatly contributed to our understanding of the functions and effects of war. Indeed, in the case of Cowra as depicted by Alison Starr in this special issue, the Homefront could be a place where the global dimensions of the war were most realized with the prison camp housing captives from all fronts of the war. As all belligerents mobilized for total war, the Homefront became an essential war front, directly tied to the fortunes of war.

Conclusion

One final thought as a means of conclusion is to consider the memory of morality of war. For the People’s Republic of China, the official memory of the Asia-Pacific War is as a necessary defense of the homeland, a narrative of resistance, victor and victim. In the case of Japan, the memoirs analyzed by Justin Aukema and Maetani Kuremitsu’s manga discussed by Matthew Allen in this special issue show the Japanese Imperial Army simply blundering its management of the war. In the discussions in this special issue, there are very few accounts of a direct encounter of the act of killing. Indeed, Maetani’s robot is the only protagonist depicted as actually killing an enemy. Veteran of the 1944-45 Battle of Leyte, Kamiko Kiyoshi, in Aukema’s essay, makes reference to being a good shot and spraying bullets at the enemy but there does not seem to be any discussion of him actually hitting anyone. The reluctance to discuss the direct act of killing may be as much part of a reticence to relive traumatic events as it is a part of a wish to avoid damaging the heroic character of the main subjects of the books.

Just as in First World War memoirs we see the soldier as an innocent victim of war; he (the combatant memory is still overwhelmingly male) does not understand the conflict around him. There is a strong sense that the war was an exercise in futility and forced a re-evaluation of what it meant to be a soldier, a subject of the Japanese empire to fulfill contemporary masculinity. This perhaps differs from the narrative put forward by the British war poets of the First World War where memory of the war meant that “older languages of grandeur and glory had to be recast in the light of the combat experience” (Winter 2017, 94). Much like the oft repeated “Lions led by Donkeys” trope of the Great War, there is not a moral rejection of war, but simply a rejection of the military leaders who blundered into war in the first place.

While its centenary is still quite a while off, in thinking about the memory of the Asia-Pacific War as part of the Second World War it is useful to look to memory studies of the First World War as a model and vice versa. As we become further removed from the end of the Asia-Pacific War, we see the generational and archival cycle which allows the maturation of a field occurring in studies of the Second World War over the last decade in much the same way that it did for the First World War from the 1990s. Catriona Pennell and Daniel Todman (2020, 49) repeated calls for those working in First and Second World War studies to focus on the cultural history of war and that a lot can be learned from looking at our collective historiographies. One of the goals of this special issue is to highlight the popular memory of war culture of the Asia-Pacific War and connect our findings with memory studies of the Second World War in general. It is important that we stimulate a conversation and think about how the general public will perceive the commemorative cycles that will no doubt dominate studies of the global Second World War as we leave the seventy-fifth anniversary behind and gradually approach the centenary of the war’s end in 2045.

References

Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane, and Becker, Annette. 2002. 14-18: Understanding the Great War. New York: Hill and Wang.

Barclay, Paul D. 2021. “Imperial Japan’s Forever War, 1895-1945.” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Vol. 19, Issue 18, No. 4: 1-30.

Conrad, Sebastian. 2014. German Colonialism: A Short History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

De Meneses, Filipe Ribeiro and Pennell, Catriona. 2019. “Introduction.” In De Meneses Filipe Ribeiro and Pennell Catriona (eds.) A World at War 1911-1949. Leiden: Brill, 1-15.

Dower, John. 2000. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York: WW Norton & Company.

Ellingson, Ter. 2001. The Myth of the Noble Savage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Faulkner, Neil. 2017. Lawrence of Arabia’s War: The Arabs, the British and the Remaking of the Middle East in WWI. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fujitani, Takashi, White, Geoffrey, and Yoneyama, Lisa (eds). 2001. Perilous Memories: The Asia-Pacific Wars. Durham: Duke University Press.

Gerwarth, Robert, and Malinowski, Stephan. 2009. “Hannah Arendt’s Ghosts: Reflections on the Disputable Path from Windhoek to Auschwitz.” Central European History 42: 279-300.

Goebels, Stefan, 2007. The Great War and Medieval Memory Remembrance and Medievalism in Britain and Germany, 1914–1940. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hettling, Manfred and Schölz, Tino. 2019. Translated by Nicholas Potter. “Bereavement and Mourning.” In Ute Daniel and Peter Gatrell et al. (eds.) 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Berlin: Berlin Freie Universität.

Horne, John. 2008. “Defeat and Memory in Modern History.” In Jenny MacLeod (ed.) Defeat and Memory: Cultural Histories of Military Defeat in the Modern Era. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 11-39.

Horne, John. 2014. “The Great War and Centenary.” In Jay Winter (ed.) The Cambridge History of the First World War (Vol III). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 618-639.

Izao, Tomio. 2017. “The Role of the Siberian Intervention in Japan’s Modern History.” In Rinke, Stefan and Wildt, Michael (eds.) Revolutions and Counter-Revolutions: 1917 and its Aftermath from a Global Perspective. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 161-177.

Jünger, Ernst. 1920. In Stahlgewittern. Stuttgart: JG Gotta’sche Buchandlung.

Kramer, Alan. 2007. Dynamic of Destruction: Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leonhard, Jörn. 2018. Der überforderte Frieden: Versailles und die Welt 1918-1923. Munich: CH Beck.

Lewerenz, Susan. 2010. “Loyal Askari and Black Rapist: Two Images in the Discourse on National Identity and their Impact on the Lives of Black People in Germany, 1918-45.” In Perraudin, Michael and Zimmerer Jürgen (eds.) German Colonialism and National Identity. New York and London: Routledge, 173-186.

Lindstrom, Lamont. 2001. “Images of Islanders in Pacific War Photographs.” In Fujitani, Takashi, White, Geoffrey, and Yoneyama, Lisa (eds.) Perilous Memories: The Asia-Pacific Wars. Durham: Duke University Press, 107-128.

Mosse, George L. 1990. Fallen Soldiers, The Memory of the World Wars. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moyd, Michelle. 2011. “We Don’t Want to Die for Nothing: Askari at War in German East Africa, 1914-1918.” In Das, Santanu (ed.) Race, Empire and First World War Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 90-107.

Nora, Pierre. 2002. “Reasons for the Current Upsurge in Memory”. Eurozine, 19 April 2002. [Accessed 26 August 2021].

Pennell, Catriona and Todman, Daniel. 2020. “Introduction: Marginalised Histories of the Second World War.” War & Society 39, No. 3: 145-154.

Saaler, Sven, and Schwentker, Wolfgang (eds.) 2008. The Power of Memory in Modern Japan. Folkestone: Global Oriental.

Samson, Anne. 2013. World War I in Africa: The Forgotten Conflict Among the European Powers. London: I.B. Tauris.

Schivelbusch, Wolfgang. 2003. The Culture of Defeat: On Trauma, Mourning, and Recovery London: Granta Books.

Stibbe, Matthew. 2020. Civilian Internment during the First World War: A European and Global History 1914-1920. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Takenaka, Akiko. 2015. Yasukuni Shrine, History, Memory, and Japan’s Unending Postwar. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Winter, Jay. 2017. War Beyond Words: Languages of Remembrance from the Great War to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zantop, Susanne. 1997. Colonial Fantasies: Conquest, Family and Nation in Precolonial Germany 1770-1870. Durham: Duke University Press.

Notes

This issue of New Guinean recruits into the Australian armed forces during the Asia-Pacific War was discussed by Caroline Norma at the conference related to this special issue.