Abstract: This article uses the example of a children’s manga from the early 1960s to investigate how the reconstructed heroism of kamikaze can be seen in the context of postmemory. In postwar Japan the tragic character of the kamikaze has been invoked in many movies, in television dramas, and in novels, manga, and biographies. The tragedy of kamikaze has also appeared in numerous privately run sites of war memory such as the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots and Yūshūkan, the museum of the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo. Many such representations of kamikaze have portrayed the young pilots as pathetic but patriotic figures who generate strong empathy in readers/viewers that conform with the tropes associated with Marianne Hirsch’s idea of postmemory. This essay suggests that postmemory with respect to kamikaze is illusionary, and that the comic in question, Robotto Tokkōtai, is a powerful example of ironic discourse that is in fact a counter postmemory reading of the role of kamikaze. Drawing on contemporary sources’ readings of memory and postmemory, the article suggests that partial memorialization and partial amnesia go hand in hand within early twenty-first century Japan’s nostalgia for the kamikaze.

Introduction

In early 1960s Japan, perceptions of the devastating loss of the Pacific War and the long war in China gradually shifted from defeat at war to narratives of victimization and of the destruction rained down upon Japan from overseas. As the population turned from being a mobilized, militarized society to one that was pacifistic and increasingly driven by economic motives, memories of the war were repressed and recast in the public imagination. For the first generation born after the war, there were few reference points from which to engage with war memories. This generation looked forward to a bright new future, and the war, which was largely elided as a topic for discussion in the classroom and in the home, was not to be critically engaged.

Into this lacuna came a number of artefacts: novels, movies, and manga in particular. These were often produced in ways that allowed an author or director to finesse a position that engaged individuals’ bravery and stoic nature in the face of unwinnable odds, a theme had that had some connections to a number of prewar and immediate postwar jidaigeki.1 These familiarly themed forms of popular culture were widely popular. Such films, novels and manga played an important role in reimagining the war experience, but their premises were often somewhat banal, or at best rather pointedly anachronistic.

Among these products of Japanese pop culture, stories about tokkōtai – the Special Attack Forces, known colloquially as kamikaze – were popular. Many were autobiographies of ‘failed’ tokkōtai pilots, or analyses of kamikaze strategies. In fiction, idealising the tragic trajectories of young men’s short and patriotic lives, stories about the tokkōtai like Toyoda’s Kōgeki-tai hasshin seyo! (Start the Attack Corps!) (1974) were presented as uplifting examples of the deep Japanese commitment to emperor, nation and family. Starting from the end of the war, a number of films were made of tokkōtai, many pursuing themes of the national need to mourn the deaths of so many young ‘living gods’ (Nakayama, 2017). Films in this genre included ‘The Maidens’ Base’ (1945), ‘The Last Homecoming’ (1945), ‘Proposal’ (1953), ‘Hibiki’ (1957), ‘Tombstone in the Clouds’ (1957), and ‘Last Sento Machine’ (1965).2 Tokkōtai were seen to be tragic but heroic figures, and potential role models for young contemporaneous Japanese people. These characters, and those that preceded them, generate in some Japanese observers deep feelings of ‘gratitude’ and of ‘affect’ (Ahmed, 2014).3 It is possible to confuse these responses with perceptions of ‘postmemory’ which I discuss below.

Using Marianne Hirsch’s (2008, 2012) notion of postmemory, in this article I try to develop a position that I refer to as ‘counter postmemory’. This engages postmemory’s central premise, which, simply put, is that in the years following the war the trauma of events that victims of war endured was so intense that the next generations related to those victims experienced traumatic ‘postmemory’ themselves. That is, they experienced almost viscerally the pain of others (Hirsch, 2012). This concept was used particularly to articulate the experiences of families of victims of the Holocaust. Unlike Hirsch’s formulation, however, I propose that in Japan’s case the second generation after the war had few immediate links to the trauma of war that preceded the present day. While there are events that are etched in the popular consciousness, such as the fire-bombing of Tokyo4 and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, these traumatic incidents are linked to notions of Japan as victims of war atrocities. Arguably these narratives of victimhood are the dominant narratives of Japan’s experience in the Pacific War (Hicks, 1997; Orr, 2001; Seaton, 2007). The horrific nature of the events, and the significance of the survivors’ narratives in contemporary peaceful citizens’ movements cannot be underestimated. However, quite distinct from the Holocaust, where postmemory was generated in response to unrequited human cruelty, the subtext of causality cannot be overlooked. In Japan’s case, the causes of the war are indeed often overlooked, giving rise to multiple representations of Japan’s victimhood (Hicks, 1997, Jeans, 2005, Lim, 2010, Seraphim, 2008).

I would like to note that this is not the case in Okinawa, however. In Okinawa the postmemory is thriving. Ironically, this is largely due to the continuing presence of the US and Japanese military bases that occupy a disproportionate amount of the landmass of the main Okinawa island that keeps the memory of war in the foreground of many people’s thoughts.5 On top of this, the fact that between one quarter and one third of the Okinawan population perished at the hands of either the US or the Japanese soldiers’ actions, and the continued presence of those perpetrators of atrocities, serve to reinforce the memory of diabolical actions of the past. A further irony is that almost all the kamikaze attacks to ‘defend’ Japan took place in the waters around Okinawa.

In this article I focus on one popular cultural artefact from the postwar period, Robotto tokkōtai (Robot Kamikaze), by Maetani Koremitsu, written in 1962. This story is in the third manga book in the series of the adventures of the Robot Sailor (Robotto suihei), which started in 1958. It is a farcical manga and is intentionally obtuse. It satirizes the nature of the Japanese military command structure, the content of the commands, the chain of command and confuses the narratives of patriotism so dominant in literature about tokkōtai. In the example below, I look at the story that sees Robot6, the lead character, transformed into kamikaze.

Robotto Tokkōtai, the manga

The author, Maetani Koremitsu (1917-1974) was a former propaganda artist for Tōhō, who was drafted into the Japanese military to serve in Burma in 1939 and was subsequently sent to China for the duration of the war. His best-known manga series, Robotto Santōhei (Third Class Soldier Robot), is written in slapstick-style, and centered around the character Robot, a third-class soldier. Included in this popular manga series (which was first published from 1955 to 1957, and later as a twelve-volume set from 1958), was Robotto Tokkōtai. It was intended to be a critique of war, and focused on a reluctant robot, who had been developed to become a super soldier for the Japanese Navy.7 The manga was very popular into the 1960s, appearing in Weekly Shōnen Sunday, a manga omnibus aimed at Japan’s youth from 1962 to 1965.

Robot tries to help his humans as much as possible, but often doesn’t function as well as he should. However, he is largely indestructible. This leads him to take on the enemy in unpredictable ways. He also has a profound sense of the ironic, and a need for self-preservation, two character traits that were not desirable in a ‘super soldier’, nor indeed in any Japanese service personnel.

Fig 1. The title page.

In Robotto tokkōtai, the story picks up from Maetani’s previous manga, in which Robot has survived after being given a ‘crash course’ (pun intended) on how to fly an airplane. His mission to attack an American ship in a biplane armed with a number of bombs is farcically unsuccessful as he has not mastered how to fly the plane, and he has crash landed in the ocean near an island in Guadalcanal Province in the Solomon Islands. He considers committing suicide but realizes it is impossible to cut himself as his steel belly will not allow that to happen. So, he decides to return to the ship. He ‘borrows’ an enormous basin used to wash clothes from natives on the island (portrayed as big lipped, wide nosed and dark) and paddles back to Japanese shipping lanes in the Pacific. The natives shout at him to return the basin, but he says he’ll return it after the war is over.

Fig 2. Robot steals the basin to return to his ship.

His captain welcomes him back to the ship, asks him how he got back, and reprimands him for losing his airplane. He then tells Robot about the new strategy being developed by Tokyo – that of the Special Attack Forces, this time specifically for the Navy. Robot asks him what exactly that is:

‘It is when a Navy sailor attaches a torpedo to a midget submarine and drives it into the hull of an enemy ship, killing himself and destroying the ship,’ the captain tells him.

‘Really??? What are you saying?’ replies Robot, ‘what kind of idiot would do that?’

‘It’s you sailors who will!’ the captain replies.

‘That’s shocking!’

‘You’ll be treated as heroes and War Gods!’

‘Outrageous!’

‘There are heaps of other sailors who are keen to do such things,’ Robot points out to the Captain.

‘Don’t talk such rubbish,’ one of the other sailors replies.

The captain looks at the other sailors and says, ‘You all want to become War Gods, don’t you?’

‘This is not a joking matter!!’ they yell out, shocked, in unison.

The captain is mightily angered. ‘Inexcusable! You should all be prepared to lay down your lives for the sake of the nation.’

Because they are all so reluctant to go to certain death, his first officer proposes they play rock paper scissors with the other sailors to decide who will be the skipper of a new midget submarine in the Special Attack Forces. Robot loses.

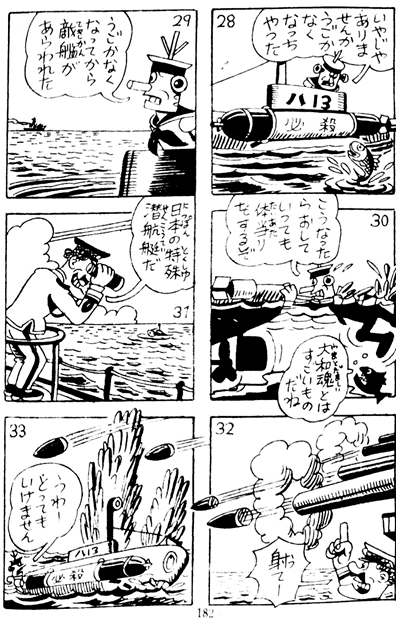

Fig 3. Robot loses at ‘rock, paper, scissors’.

‘It’s always me with my head in the noose,’ he laments as he’s shown the midget submarine he will pilot with the torpedo attached. It’s labelled ‘Hissatsu‘ – Deadly Skill. ‘When your mission has been successful, you will become a war god,’ the captain tells him. Unconvinced, Robot boards the submarine and leaves the ship. As he heads out to sea, Robot says he hopes that he doesn’t get lost at sea.

After some time searching for enemy ships, the sub breaks down and stops in the water. He sees an enemy ship in the vicinity, and he tries to move the submarine away from it by jumping over the back and swimming it away from the path of the ship. The ship spies his midget submarine as he tries to flee. He dives underwater to escape. A nearby fish remarks that this is behavior unbecoming for a tokkōtai.

Fig 4. Robot’s submarine breaks down and he is fired upon by the enemy.

After Robot has swum away, the enemy ship fires at him, sinks his submarine and continues on its way, but runs over the wreck of the mini submarine with the torpedo still attached to the hull. The resulting explosion sinks the enemy ship.

From a distance the captain of his ship sees the explosion and assumes that it is Robot doing his job as kamikaze. ‘He has made the ultimate sacrifice for us all and destroyed an enemy ship,’ he says observing the action through binoculars.

Fig 5. The enemy ship destroyed, the captain comments on what a great job Robot did.

‘What an excellent job,’ the captain says as they steam over to observe the wreckage up close. ‘I think it’s amazing that the tokkōtai plan worked so well.’

‘However, I’ll miss Robot, even though I know he has now become a War God.’

‘He’ll be promoted to 2nd Lieutenant along with his promotion to War God.’

Hearing this from the water, as he clings to some wreckage, Robot says, ‘Can’t say I’m unhappy with that’.

He launches himself from the water, a big grin on his face, ‘Captain, you weren’t lying when you said I’d made 2nd Lieutenant, were you?’

Fig 6. Robot launches himself from the water to the shock of the captain.

The Captain is shocked – Good lord, it’s the ghost of a War God!’

‘No, I’m not a ghost – see I have real legs. I just want to be a 2nd Lieutenant, like you said’.

‘I can’t say strongly enough what a great job you did, so we need to support you.’ the captain says.

The petty officer realizes that Robot is now his superior, and Robot soon puts him to work scrubbing the deck. ‘I think I’m going to hate the Navy from now on,’ the petty officer says.

Commentary

This episode of Robot mocks the military strategy of self-sacrifice. Robot’s cavalier and self-centered attitude, generated through his superhuman status, the notion of war gods, and the importance of sacrifice are themes central to the dialogue. There is little respect for the ideas of the state in producing ‘tragic hero’ soldiers who die for the nation in this manga. This was in contrast to many of the manga focusing on triumphant narratives that appeared in the late 1950s and 1960s, such as Tsuji Naoki’s 1963 Zero-sen Hayato (Hayato the Zero Pilot, 1963) and Sagara Shunsuke and Sonoda Mitsuyoshi’s Akatsuki Sentōtai (Dawn Combat Unit, 1967). Nakar (2003) has written extensively on the theme of triumphalism in such manga of this period, focusing on the exploits of pilots and their strategies to defeat the enemy.9

The characterization of Robot as an indestructible being, sent to die for the sake of the nation, which of course he is unable to do, is irony played large in Maetani’s writing. Whether this irony was readable by junior high school students who presumably constituted the readership of this manga is unknown.10 However, looked at from more than 75 years after the war it is hard to imagine that a current audience would overlook this irony.

By focusing on the robot’s unswerving self-interest, Maetani is able to set him up as a character who is in complete opposition to contemporaneous values of what it meant to be both a Japanese soldier and a kamikaze.11 The robot’s aim is to be promoted to 2nd Lieutenant, but again the irony is that the promotion to 2nd Lieutenant is only possible if the kamikaze died in the attack. In other words, it was to be a posthumous award, with the implications that the family of the dead officer would be taken care of by the Japanese state. Of course, Robot does not have a family, so there would be no beneficiaries of his death. It is the immediate, present award of this promotion that motivates Robot to leap aboard the ship, even as the captain exclaims he is the ‘ghost’ of a war god.

Simply expressed, Robot could be a metaphor for contemporary (1960s) Japanese society; self-centered, self-interested, and largely solipsistic. His existential focus on comfort and survival would reinforce this perspective and is clearly at odds with the attitudes of those who experienced the trauma and desperation of Japan’s military at the end of the Pacific War.

In the above context, Maetani’s personal experience as a soldier in China and Burma from 1939 no doubt influenced his writing and illustrating style. His criticism of the military leadership was outspoken, and Robot became the vehicle for this dissatisfaction. Underscoring all the above farcical storyline and characters is his notion that war is not glorious at all. It is presented as bureaucratic and ineptly conducted. The sailors are all suitably reluctant to voluntarily sacrifice themselves for the nation. In particular, the message that the Japanese military was incompetent on multiple levels, regardless of their technical capacity (to design a super robot!), suggests that Maetani was committed to lampooning the folly of fighting a war that could not be won with the resources available. Moreover, using Robot in his metaphorical role as a wannabe kamikaze (who didn’t want to be kamikaze) demonstrates his disenchantment with the idea that there was anything noble about the way life was sacrificed for the nation during the war.

Perhaps too it is worth noting that while Robot was primarily an ironic invention who served a metaphorical purpose for Maetani, he could also be perceived as a fragile and ephemeral character. As something made of metal his life as a sailor was inevitably a limited one – his ‘indestructible’ nature notwithstanding – as salt and salt water are inimical to the metal of which he was constructed. In this context he may also be seen to represent the ephemerality of the Japanese military at large – certainly the Navy.

Postmemory and its antithesis

Marianne Hirsch (2008) proposed that in the case of the Holocaust, the generation once removed from the experience of war was so closely linked through photography, trauma and emotion that the term ‘postmemory’ could be used to describe what it was that this generation experienced.

I see it [..] as a structure of inter- and trans-generational transmission of traumatic knowledge and experience. It is a consequence of traumatic recall but [..] at a generational remove (2008: 207).

There is a sense that war and memory are linked so powerfully through the experiences of families, friends and others close to the succeeding generation that it is as though the new generation actually experiences the trauma of the Holocaust on a personal level. What Susan Sontag (2003) calls ‘the pain of others’ can be seen also as the (referred) pain of the new generation. That is, the new generation experiences the pain of war vicariously, but in close emotional proximity to the actual pain of those who were victims of the violence.

As Hirsch states, ‘at stake is precisely the “guardianship” of a traumatic personal and generational past with which some of us have a “living connection” and that past’s passing into history’ (2008: 104). It is this transformative effect, or literally the ‘affect’ of the transformation that is the focus of Hirsch’s approach to understanding and then learning from the violence that was precipitated by the Holocaust. This struggle to understand the inhumanity of the actions taken by Nazi Germany against Jewish people underscores the attempt to define ‘postmemory’.

Although it may be drawing a long bow to link memories of Japan’s military aggression with discussions about the Holocaust (see Sakamoto, 2015 and Fukuma’s 2019 critique of such approaches), arguably in Japan the experiences of victimhood which followed the firebombing of Tokyo and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki could be seen to have similarly recurrent nightmarish connotations (Kitamura, 2010, Jeans, 2005, Takenaka, 2016). The circumstances in Okinawa where so many civilians perished at the hands of both the US and their own Japanese ‘protectors’ could also be seen to have generated postmemory within the Ryukyu archipelago (Allen, 2002, Cook and Cook, 2002, Kitamura, 2010). However, there remain significant lacunae that are unspoken: in Japan’s case the US bombings were in response to Japanese decisions taken at the highest level to provoke the US to enter World War 2—and Japanese terror bombings of Chinese cities, in particular Chongqing. The situation on Okinawa was pre-empted on a similar basis. That is, Japan had pushed the US to enter the war and a military response was inevitable (though the Japanese cruelty directed towards Okinawans was more difficult to rationalize).

The Holocaust, which was perpetrated systematically and without provocation against the Jewish people by the Nazis and indiscriminately conducted against all Jewish people in the attempt to commit genocide, generated entirely different modes of experience and recollection from those engendered by the memories of kamikaze warfare in the last-ditch effort to protect the Japanese homeland (while simultaneously sacrificing Okinawa). Moreover, while for those survivors of Auschwitz and other death camps in which Jews were slaughtered by Nazis it is entirely legitimate to recall, retell and attempt to redress the violence meted out against them, in the case of Japan’s experience in war it is more difficult.

For the purposes of this article, the case of the kamikaze is employed to provide an alternative model of remembering to the idea of postmemory. Although many Japanese, conspicuously including former Prime Ministers Koizumi Junichirō and Abe Shinzo,12 have lionized the tokkōtai as shining examples for Japanese youth to follow, the reality of being tokkōtai was not as noble as it was made out to be by recent politicians. In fact, it was, unsurprisingly, decidedly traumatic (Furuta, 2014). Pilots were not given choices about whether to volunteer or not (Ohnuki-Tierney 2002, 2010). Those who were sent on missions were often very young, some as young as 17 years old. There were even Korean colonial subjects recruited to die for the Japanese Empire.

In the manga analyzed here, Robot is the ‘anti-hero’ hero,13 a role he invariably plays throughout this manga series. He embodies the antithesis of what was regarded as the ideal tokkōtai. He cared not at all for the nation, nor for his fellow crewmates, nor did he display valor, or indeed enthusiasm for his impending and inevitable demise. He resisted the urge to actually self-destruct in his final act against the enemy. But he enthusiastically received the ‘posthumous’ promotion and the relief from the menial duties he had conducted before he lost the ‘rock paper scissors’ contest that led to him becoming tokkōtai. In short, he is the anti-tokkōtai.

Unlike the character of Tetsuwan no atomu (Astro Boy), a manga series written between 1952 and 1968 by the ‘father of Japanese manga’, Tezuka Osamu,14 Robot is a character with built-in flaws (and potentially an inevitable trajectory towards rusting and irrelevance) and no chance of redemption. And while he is mechanical and a constructed creature, at the same time he is seen as ultimately (and ironically) human in his foibles and weaknesses. Indeed, he is perceived as a being who is more flawed than the humans he associates with.

It is this separation from the historical narratives that were being generated in the 1960s about the war that makes his position so interesting as a counter postmemory figure. While Hirsch has emphasized the trauma of war and memory, Robot epitomizes the ridiculousness of war and amnesia/memory. Some have written about how they, personally, are moved by the postmemory of experience through the affective process of humanizing15 the subject of the tokkōtai pilots at museums like Yūshukan in Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo (Sakamoto, 2015).16 Currently, however, this is not the second generation after the war. Indeed, more than 75 years after the war this is now four generations removed from the actual fighting. And it is important to acknowledge that the positionality of today’s observer is informed by a plethora of materials – novels, films, television programs, manga, and sites of memorialization of kamikaze such as the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots – available in the popular cultural domain that reinforce the sentimentality of such readings of the ‘cherry blossoms’.17

The approach of Maetani, with his highly cynical reading of the nature of war, the pointlessness of self-sacrifice, and the relentless self-interest of Robot in his efforts to make his life more comfortable offer an alternative interpretation of the trope of self-sacrifice for the state. This interpretation is a counter postmemory approach. As Standish has demonstrated convincingly, the tragic hero in Japanese cinema was a recurring motif in films about the kamikaze in the 1950s and 1960s (2000:79). Robot categorically was not a tragic hero. Rather than relying on the emotional emptiness of calls to celebrate the selfless actions of young men, called on by the state to die in the call of duty (the notion of individual sacrifice for the larger good), as described by Standish (2000), in this instance Robot’s self-serving attitudes, his views on the futility of war and the pointlessness of sacrifice for the state inform the overall position that war is simply stupid.

It is relevant to point out at this juncture that in the 1960s many also shared Maetani’s view that the sacrifice of kamikaze was a pointless enterprise. While there is a powerful conservative tendency to apotheosize the role of the kamikaze, there was, and remains, considerable doubt over the integrity of the strategy.18 As Maetani’s Robot demonstrates, the senselessness of sacrifice is not something that can be glorified, but instead is something to be angry about. It is the end of sense and the beginning of nonsense. It is also quite literally the beginning of the end.19 And it is Robot who can point these human weaknesses out to the readers, who might still be in some doubt about the sacrifices of their forebears.

These unspoken views, inferred through the story, stand in strong contrast to the narratives of sacrifice produced at sites like the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots or Yūshukan, which may well be relying on the idea of emotional connectedness or even affect to generate a sense of postmemory (Allen and Sakamoto, 2013, Fukuma, 2019, Perkins, 2011, Sakamoto, 2015, Seaton, 2019). However, the chimerical nature of this phenomenon, reproduced in many forums after the war – in film (Yamazaki Takashi’s Eien no zero (2013), and Furuhata Yasuo’s Hotaru (2001), for example), in books, manga and television dramas – has generated intense criticism from both surviving kamikaze pilots and trainees and from Japan’s former enemies, in particular China.

In the 1960s the Japanese state—and society at large–continued to distance itself from historical narratives of war that included any actual Japanese combat. At the same time, as we have seen, the kamikaze were becoming important ‘tragic heroes’ in popular culture in the 1950s and 1960s (Standish, 2000), a position that has continued into the present day. There were also a significant number of manga writers who contributed to the genre, many writing in the ‘tragic hero’ mode.20 Yet writers like Maetani were able to cast into doubt the need for the development of postmemory with respect to the tokkōtai. In the 2010s Prime Minister Abe may have been ‘moved’ by the film, Eien no zero and may have held tokkōtai in the highest esteem (possibly thanks to his father being a trained kamikaze who never flew a mission21), but not all writers in the years one generation removed from the war were of the same opinion, it appears.

There is no doubt that millions of Japanese experienced trauma, sacrifice, starvation, death, injury and humiliation during the years from 1931 to 1945. But in arguing for a case of postmemory in the eyes of the postwar generation, particularly with respect to kamikaze, there is a real problem with perspective. As the US Occupying Army and subsequently the state effectively removed any official glorification of Japanese military actions during the long war, state-sponsored memorialisation of war was confined to memory of the acts which led to victimhood or acts in which the enemies were removed from the narrative (Allen and Sakamoto, 2013, Bukh, 2007, Buruma, 1994, Cook and Cook, 2002). In embracing the role of the victim, when Japan was so actively also the perpetrator of many crimes against humanity, the concept of ‘postmemory’ is at best ‘post-partial memory’ and more likely ‘post-amnesia’.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Japan’s popular culture began to reflect a groundswell of thought that was highly critical of the nature of war.22 This cynicism about war, and the characterization of war as something that was deeply flawed and pointlessly self-destructive was portrayed in Robotto tokkōtai. It provides an alternative narrative to that of the ‘noble’ kamikaze, and effectively counters any claims that suicide bombers should be memorialized in ways that conform to Hirsch’s conceptualization of the transmission of trauma across generations. It is difficult to accept that there is much in common between the victims of the Holocaust and the young pilots who accepted the command to visit destruction on US, British and Australian naval personnel through self-destructing, even if it was to attempt to save their nation.

Conclusion

After the end of four years of a ‘horse loose in the hospital’23 where we have seen the hastening of the end of truth through Donald Trump’s ‘legacy of lying’,24 Robot arguably epitomizes a truth that is absent from much story-telling about Japan’s involvement in the Pacific War. From this author’s perspective, discovering Maetani’s refreshingly cynical reading of war in the 21st century has been engaging, challenging, and most of all counter-postmemory in the sense that it is not directly about the trauma of war. Robot is a farcical and ridiculous caricature of the idealized kamikaze; he is selfish, cowardly, disinterested in the nation, anti-hierarchical, insolent, disrespectful, and disobedient. In the sense that war is traumatic, and that there is a series of linkages between the past and the present, reinforced by images, stories, photographs and popular culture, it is arguable that Japan’s experience with kamikaze can be seen as part of the ‘affective economy’ (Ahmed 2004, Sakamoto 2015). But there is little doubt that the approach of Maetani, irreverent as it may appear, is attempting to move beyond this affect, and towards an interpretation of war that challenges the notion that kamikaze fighters were somehow pure and untarnished victims of the cruelty of war itself. Rather he sees them as a consequence of the system that invented, then manipulated them into dying in such large numbers for the emperor and nation.

Robot, then, is the antithesis of what war is about for many apologists of the actions of the Japanese elite in the Pacific War, as expressed in numerous privately-run museums and sites of memory in Japan, like Yushukan in Tokyo, or the Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots in Chiran. His position is also evidence that there were those in the 1960s whose views were highly critical of the actions of the military during the war. And his story stands in juxtaposition to those who promote Japan’s re-involvement in political and military actions overseas, a course that was relentlessly pursued by former Prime Minister Abe.

In an era of post-truth, dominated by populist and revisionist readings of history and current events, Robot stands out as a surprisingly truthful, if potentially controversial character, in the sense that his position is in contradistinction to right wing readings of the role of kamikaze. Unmasking the war as farce, his role, while superficially that of the clownish ‘anti-hero hero’, is also to be an adept critic of kamikaze as figures of postmemory. His honest engagement with the often mendacious narratives that have dominated memory of the kamikaze role in the Pacific War sits uncomfortably with the seemingly endless homages to tokkōtai that inform much wartime nostalgia in many parts of Japan today.

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2004. “Collective feelings: or, the impressions left by others.” Theory, Culture and Society, 21 (2): 25–42.

Allen, Matthew. 2002. Identity and Resistance in Okinawa, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Allen, Matthew and Sakamoto Rumi. 2013. “War and Peace: War Memories and Museums in Japan.” History Compass, 11 (12):1047-1058.

Bukh, Alexander. 2007. “Japan’s History Textbooks Debate: National Identity in Narratives of Victimhood and Victimization.” Asian Survey, 47 (5): 683-704.

Buruma, Ian. 1994. The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Cook, Harako, and Cook, Theodore. 2003. “A Lost War in Living Memory: Japan’s Second World War.” European Review, 11 (4): 573-593.

Dower, John. 1986. War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War. New York: W.W. Norton.

Dower, John. 1999. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Aftermath of World War II. New York: W.W. Norton.

Figal, Gerald. 2012. Beachheads: War, Peace, and Tourism in Postwar Okinawa, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Frühstück, Sabine. 2017. Playing War: Children and the Paradoxes of Modern Militarism in Japan, Berkeley. University of California Press.

Fukuma, Yoshiaki. 2007. Junkoku to hangyaku: “tokkō” no katari no sengoshi. Tōkyō: Seikyūsha.

Fukuma, Yoshiaki. 2019. “The Construction of Tokkō Memorial Sites in Chiran and the Politics of ‘Risk-free’ Memories.” Japan Review, 3: 247-270.

Furuta, Ryō. 2014. Tokkō Sōseki no bijutsu sekai. Tōkyō: Iwanami shoten.

Hicks, George. 1997. Japan’s War Memories: Amnesia or Concealment? Aldershot: Ashgate.

Hirsch, Marianne. 2008. “The Generation of Postmemory.” Poetics Today, 29 (1): 102-128.

Hirsch, Marianne. 2012. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and visual culture after the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hosaka, Masayasu. 2005. “Tokkō” to Nihonjin. Tōkyō: Kōdansha.

Jeans, Roger. 2005. “Victims or Victimizers? Museums, Textbooks, and the War Debate in Contemporary Japan.” The Journal of Military History, 69: 149-54.

Lim, Jie-Hyun. 2010. “Victimhood Nationalism and History Reconciliation in East Asia.” History Compass, 8 (1): 1-10.

Lummis, C. Douglas. 2015. “Okinawa: State of Emergency.” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. Vol. 13, Iss. 8, No. 1.

Lummis, C. Douglas and Higa Tami. 2019. “Every day except Sundays, holidays and typhoon days, Okinawans confront the US military at Henoko, site of a planned new base.” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. Vol. 17, Iss. 8, No. 3.

McCormack, Gavan. 2016. “Japan’s Problematic Prefecture – Okinawa and the US-Japan Relationship.” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. Vol. 14, Iss. 17, No. 2.

Maedomari, Hiromori. 2020. “Okinawa Demands Democracy: The Heavy Hand of Japanese and American Rule.” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. Vol. 18, Iss. 16, No. 4.

Maetani, Koremitsu. 1955-1957. Robotto santōhei. Tokyo: Kotobuki Shobo.

Miyamoto, Masafumi. 2006. “Tokkō” to izoku no sengo. Tōkyō: Kadokawa Shoten, 2005. Mori Shirō. Tokkō to wa nani ka. Tōkyō: Bungei Shunjū.

Nakar, Eldad. 2003. “Memories of Pilots and Planes: World War II in Japanese ‘Manga,’” 1957-1967.” Social Science Japan Journal, 6 (1): 55-76.

Nakayama, Hideyuki. 2017. Tokkōtai eiga no keifugaku. Hasien nihon no aitō geki. Tokyo: Iwanami.

O’Dwyer, Sean. 2010. “The Yasukuni Shrine and the competing patriotic pasts of East Asia.” History & Memory, 22 (2): 147–177.

Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko. 2002. Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms and Nationalism: The Militarization of Aesthetics in Japanese History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko. 2010. Kamikaze Diaries: Reflections of Japanese Student Soldiers. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Orr, James. 2001. The Victim as Hero: Ideologies of Peace and National Identity in Postwar Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Ota, Masahide. 2000. Essays on Okinawa Problems. Naha: Yui Shuppan.

Perkins, Charles. 2011. “Inheriting the legacy of the souls of the war dead: linking past, present and future at the Yūshūkan.” Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies.

Sakamoto, Rumi. 2015. “Mobilising affect for collective war memory: kamikaze images in Yushukan.” Cultural Studies, 29 (2): 158-184.

Seaton, Philip. 2007. Japan’s Contested War Memories. London: Routledge.

Seaton, Philip. 2019. “Kamikaze Museums and Contents Tourism.” Journal of War and Culture Studies, 12 (1): 67-84.

Seraphim, Franzisca. 2008. War Memories and Social Politics in Japan: 1945-2005. Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Asia Center.

Sheftall, Mordecai G. 2005. Blossoms in the Wind: human legacies of the Kamikaze. New York: NAL Caliber.

Sontag, Susan. 2003. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Standish, Isolde. 2000. Myth and Masculinity in the Japanese Cinema: Towards a Political Reading of the ‘Tragic Hero.’ Abingdon: Routledge.

Takenaka, Akiko. 2016. “Japanese Memories of the Asia-Pacific War: Analyzing the Revisionist Turn Post-1995.” The Asia-Pacific Journal, vol. 14, iss. 20, no. 8, 2016.

Takeyama Yu. 2001. Hotaru. Tokyo: Toei.

The Asahi Shimbun.2010. “The Great Tokyo Air Raid and the Bombing of Civilians in World War II.” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, vol. 11, iss. 2, no. 10.

Toyoda, Minoru. 1974. Kōgeki-tai hasshin seyo! Tokyo: Mainichi Shinbunsha.

Van der Does Ishikawa, Luli. 2015. “Contested memories of the kamikaze and the self-representation of Tokkōtai youth in their missives home.” Japan Forum, 27 (3):345-379.

Notes

Historical dramas. In particular I’m thinking here of the films of Kurosawa, whose tortured but ultimately vindicated heroes are able to endure great hardship for the sake of others – ‘Sanshirō Sugata’, ‘Rashomon’. ‘Seven Samurai’, ‘Yōjimbo’, and ‘Sanjurō’ for example.

More recently in films such as Hotaru (‘Firefly’) (2001) and Eien no zero (‘The Eternal Zero’) (2013), there is emphasis placed on the conflicts between the love of family, country and duty.

In 2015 I reviewed the visitors’ books in both Chiran (Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots) and Yūshūkan, and noted the large number of comments about these emotions felt by visitors in response to exhibits of kamikaze.

These factors, plus the ongoing protest movements directed at Tokyo and Washington to remove the bases from Okinawa, have seen the transmission of the events of the last year of the Pacific War through the generations. It should be noted, though, that for the purposes of this article Okinawa holds a unique position within Japan, and its case is somewhat different to the rest of the archipelago for a number of reasons: its highly varied ethnicity and multiple languages and dialects, its idiosyncratic history and its late nineteenth century incorporation into larger Japan, the long term discrimination by the mainland against Okinawans, the presence of the US and Japanese military bases, and the extreme sacrifice called for in defence of the mainland in 1945 to mention just a few. There are many works available on protests, identity and conflict within Okinawa in recent years including multiple works by writers who have contributed to Japan Focus. These include Lummis, McCormack, and Maedomari to name a few.

The idea of the ‘super soldier’ was proposed by Dower (1986) in his War Without Mercy (p.141) where he discusses at length the propaganda war between the US and Japan, in which Japan’s soldiers were seen by the United States as both ‘super’ and as ‘monkeys’. Robot being developed as a ‘super soldier’ perhaps refers to such impressions.

In Otaku Erīto, a publication concerned with significant political and other famous people’s previous lives as being obsessed with manga, former Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama’s favourite manga was listed as Robot.

https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2009-09-24/prime-minister-hatoyama-past-otaku-views-summarized

See Eldad Nakar (2003) ‘Memories of pilots and planes: World War II in Japanese “manga”, 1957–1967’.

The inclusion of the Robot’s naval exploits in the Sunday Shonen Manga in the early 1960s suggests the readership was largely junior high school boys, as these were the target audience for the manga.

For commentary on what it meant to be kamikaze during the Pacific War, there are many and varied accounts. See, for example, Fukuma (2007), Hosaka (2005), Miyamoto (2005), Mori (2006), Ohnuki-Tierney (2010), Sheftall (2005).

See the op-ed from the Los Angeles Times, by David Leheny, for example, titled ‘Shinzo Abe’s Appeal to Nationalism and Nostalgia’ (Los Angeles Times; Los Angeles, Calif. [Los Angeles, Calif]02 Aug 2019: A.11).

Thanks to Justin Aukuma whose conception of ‘anti-hero-hero’ seems to fit this characterisation rather nicely!

Astroboy was a science fiction manga series about a scientist whose son died, and he rebuilt him into a superhuman robot, who became a force for social justice. It was immensely popular in the 1960s.

As Sven Saaler reminds me, the process of ‘humanising’ the kamikaze may really be akin to apotheosing them, placing them on a higher plateau than the mere humans who appreciate their efforts.

Others like van der Does-Ishikawa (2015) have produced more nuanced and contestable readings of tokkōtai origins, and particularly the nature of the young men who became kamikaze.

The tokkōtai were colloquially known as ‘cherry blossoms’ due to their bright, fragile and beautiful existence (Sheftall, 2005).

See Nakar’s (2003) work for a detailed account of those manga writers who emphasised the triumphal Japanese air force, for example.

The kamikaze strategy was a last, desperate strategy developed by the Japanese military to protect the home islands, so it was literally the beginning of the end of the war.

For readers interested in looking at contemporary war manga from the 1950s and 1960s as a point of comparison with Robotto, works by Mizuki Shigeru, Chiba Tetsuya, Tsuji Naoki, and Sonoda Mitsuyoshi should be considered.

Shinzo Abe was apparently ‘deeply moved’ by the film, “and his wife Akie said on Facebook about the film I couldn’t stop crying,” Akie wrote on Facebook. “(The film) made me really think how we should never wage war again, and we should never, ever waste the precious lives that were lost for the sake of their country.”

The Anpo protests of 1959-60 which were directed at challenging the legitimacy of the US-Japan Security Treaty and removing US military bases from Japan were indicative of the groundswell of popular thought about peace and the legacy of war in Japan.

This is the metaphor used by comedian John Melaney to describe the Trump White House; that is, that it was like having a horse loose in a hospital. The public never knew what was going to happen next, but it was unlikely that the outcome was going to be either expected or positive.

According to the Washington Post, which kept track of the lies and misleading statements made by the former President of the United States, there were more than 30,000 of these statements during his presidency. That is a significant legacy. See Huffington Post’s report available here.