Abstract: This essay focuses on the war cemetery as a place of reconciliation, by exploring the commemoration of war dead. It describes the journey taken at the Cowra Australian and Japanese war cemeteries from postwar enmity, when the memory of conflict and loss was still raw, to a landscape of shared cultural memories (Ashplant et al. 2001). Looking at a site in which former enemies are interred in collocated spaces, it demonstrates how war cemeteries can function as performative spaces, host acts of reconciliation and sustain practices of memorial diplomacy (Graves 2014). Through the rituals of war commemoration regularly performed at the cemetery, and negotiated within a transcultural setting, it shows how these war cemeteries offered a comparatively neutral space for mourning when the tension of conflict between former wartime combatants remained. As the Asia-Pacific War (1931–1945) moves beyond survivor testimony, this essay provides a useful interrogation of the role of war cemeteries as sites of memory and how the materiality of human remains figures in the continuing evolution of war memory to post-memory (Hirsch 2008).

Keywords: Cowra Breakout, prisoners of war, war dead, war cemetery, transcultural memory, Asia-Pacific War

Introduction

In the early hours of a cold winter’s morning on 5 August 1944, Japanese prisoners of war (POWs) staged a mass escape from the No 12 prison camp at Cowra, NSW, Australia. Known as the Cowra Breakout or Cowra Incident (hereafter “the Breakout”), the escape attempt eventually resulted in the deaths of over two hundred Japanese prisoners and five Allied service personnel. The deceased prisoners were subsequently buried in the days following in the south-eastern corner of the Cowra civil cemetery in an area designated for war burials. The Cowra war cemetery later expanded with the relocation of Japanese civilian and military wartime remains in 1964. It has since become a site of pilgrimage for Japanese visitors and a setting for memorial diplomacy between Australia and Japan (Bullard 2006).

War cemeteries are places to formally recognize military dead, provide a collective space to remember war loss, and the sacrifice of lives lost in military service. The designation of a burial space as a war cemetery, above and beyond a civil cemetery, demarcates it as distinctive, generating feelings of reverence and nostalgia. Moreover, it reveals the privilege accorded to military dead that mirrors societal militarization more broadly, which is especially relevant to societies at war. Despite the accessibility afforded by the garden cemetery movement from the mid-nineteenth century, as heterotopic spaces cemeteries are not only separated from the ordinariness of everyday life but also function as sites of “temporal discontinuity” (Foucault 1986). They are simultaneously places that mark time (with human remains creating an archaeological record) and ones which break from it (death representing the rift, where time has stopped). Unlike war memorials, “where the dead were symbolically brought home” (Winter 1995, 98), war cemeteries hold the tangible evidence of the human cost of conflict. They represent the remaining link between the living and the dead. With war remains often in distant locations or never recovered, the confirmed knowledge of a loved one’s final location in a war cemetery was all the more cherished, providing a dedicated space for engagement with the emotive aspects of mourning and remembering.

Witness accounts began to reveal the Breakout story in the postwar period, by guards (Mackenzie 1951) and prisoners (Asada 1970; Moriki 1984). Charlotte Carr-Gregg and Harry Gordon both produced publications on the Breakout, looking at its context, causes, and military judicial outcomes (1978). Carr-Gregg produced a sociological account, contextualizing Cowra with reference to the 1943 Featherston, New Zealand, incident where work refusal by Japanese prisoners resulted in the deaths of 48 prisoners and one guard. Gordon, a reputable journalist and foreign correspondent, republished with additional material on the journey since the Breakout, for the 50th anniversary commemoration in 1994. More recent publications by Bullard (2006), Tamura (2006) and Apthorpe (2008) have expanded the story, and Mami Yamada’s 2014 doctoral thesis delivered survivor interviews and investigated day-to-day activities at the camp. Recent fictional accounts have contextualized the experience of Cowra to that of Italian POWs (Keneally 2013) and the local Aboriginal population (Heiss 2016), and it has been presented on stage in both Australia and Japan (“Blood Yellow”, 1994 in Cowra; “Kaura no honchō kaigi”, 2014 in Cowra, Canberra, and Tokyo). A 2021 Japanese language documentary featured perhaps the last living link to survivor testimony (“Kaura wa wasurenai” 2021).

The collocated Cowra war cemeteries are a war memory site in Australia far from the battlefront war cemeteries of the Western Front or Gallipoli, places that resonate with Australian war memory. With few Australian service personnel repatriated, in accordance with Commonwealth agreements, battlefield tourism to these sites that embody the “secular religion” of ANZAC has remained strong (Inglis 1998; Scates 2013). Australia’s war memory is principally focused on the comradery and courage of the ANZAC myth (Sumartojo et al. 2014), later contrasted with the emaciated POW narrative of the Asia-Pacific War (Beaumont 2005; McCormack and Nelson 1993; Twomey 2018).

Though Japanese war dead are interred in formal and informal locations across the Asia-Pacific theater (see also Collin Rusneac’s contribution in this special issue), many remain unaccounted for, including those never recovered from crashed aircraft or shipwrecks in the Pacific or within former Soviet territories (Igarashi 2000). Japanese nationals have been involved in formal and informal state-sponsored bone retrieval missions since the 1950s, as well as pilgrimages to sites of significance across the Asia-Pacific theater (Trefalt 2015; see also Trefalt’s contribution in this special issue). The memory of the Asia-Pacific War for many Japanese, however, has been mainly inward-looking, vacillating between the glorification of its wartime past and recognition of it as a wartime aggressor (Seaton 2007). This is further complicated by the vexed issue of past political interest and implied war veneration at Yasukuni Shrine and its positioning within the memory realm (Saaler and Schwentker 2008, Sheftall 2008). There is a conspicuous contrast between the continued focus on Yasukuni and the lack of attention given, for example, to Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery. While victim perspectives have retained a key role in Japanese war memory, Yasukuni’s Yūshūkan Museum presents a view of conflict that remains contested despite, or perhaps in spite of, the presence of credible alternatives in the public domain (Allen et al. 2013). The Yūshūkan is notable for its curated presentation of the history of Japan’s conflicts and the materiality of war, vacillating between selected omission and mendacity.

Saito contends that when commemoration is undertaken within the lens of nationalism, this is inevitably done with insufficient recognition of “foreign others”, arguing that the presence of nationalism effectively excludes such groups from having influence in remembrance activities (Saito 2017). Likewise, Fujitani et al. present the view that Asia-Pacific War commemorations are undertaken in conjunction in wartime Allied countries but absent of Japanese participation, resulting in a disconnect between Japanese imperial expansion and its visibility in public memory (Fujitani et al. 2001, 8). This is further compounded by the idea of Japan’s “defeat remembrance” (Sheftall 2008, 54).

While the flavor of both Australia and Japan’s commemorative practices are undeniably predicated on nationalistic tendencies, the Cowra war cemeteries have resisted these paradigms that are evident in other locations in the Asia-Pacific theatre. Located on the Australian home front, with graves of older war participants and accidental wartime victims, they unusually hold the remains of both sides of the conflict: the victor and the defeated. While the Japanese cemetery has remains of air force personnel (6%) that recall the “sacrificial heroism” of kamikaze fighters (Sharpley 2020; Sheftall 2008, 57), it mostly consists of prisoners (57%), resulting from a conflict where the idea of capture was reviled; wartime civilian remains (34%); and even female internee remains (4%). Despite the war cemeteries being synonymous with the Breakout, less than half of the cemetery’s occupants resulted from it (45%).

Scholars have sought to position the Breakout story in a variety of ways: as a site of reconciliation through comparative analysis with the bombing of Darwin, another home front that experienced significant loss (Rechniewski 2012); as a site of difficult heritage, suggesting that friction between Australian and Japanese war memories remains unresolved (Kobayashi and Ziino 2009); as a “site of conscience” (Herborn et al. 2014); and by placing it within a broader wartime carceral framework and considering it as a site of heritage diplomacy (Pieris 2014; Pieris and Horiuchi 2017). While these recent contributions provide value in illuminating the story, there nonetheless remains abundant value in the early works by Carr-Gregg (1978) and Gordon (1978; 1994), with their proximity to the lived experience of the Breakout and its aftermath.

Absent is the overdue consideration of the war cemeteries as a dynamic memoryscape where enemies have met and continued to meet, and how wartime perceptions of the “other” have evolved into shared memory. When wartime enemies share a formal burial location, the effect of the binary demarcation of victor and defeated interred within the same cemetery space is twofold. Firstly, the human remains occupy an extraterritorial space in an effectively permanent capacity in a faraway and often inaccessible location, with visitation limited by distance. This is complicated by the uncertainty surrounding war deaths being reported to families during wartime when many had actually been captured, like Wakaomi Michiaki. And second, the use of a cemetery as a setting for mourning and commemorative activities invites transcultural and transnational characteristics, which must be negotiated within the context of evolving perspectives on war memory and commemoration. This manifests itself in changing attitudes, appetites for involvement, and participants. This essay considers these factors, beyond what has been presented in the literature to date: the interaction of individuals and groups within the places, events, and relationships that were generated by the Breakout.

Cowra POW Camp

Cowra is a small rural town on the traditional lands of the Wiradjuri people, located approximately 350km south-west of the NSW state capital of Sydney, with a primarily agricultural economy. Initially visited by British colonial surveyor George Evans in 1815 as part of Australia’s colonial expansion (Weatherburn 2006), British colonial pastoralists seeking land grants began to settle in the area in the 1830s, despite ongoing clashes with the Wiradjuri for several decades (Coe 1986).

The No 12 prison camp at Cowra was one of twenty-eight internment camps throughout Australia during the Second World War, holding military captives as well as civilians interned as enemy aliens sometimes in the same facility. Civilian internees were interned principally for national security purposes. Japanese civilian internment commenced after the 1941 Pearl Harbor attacks, and Japanese, German and Italians totaling around 16,700 were interned in Australia during Asia-Pacific War, as enemies of local or overseas origin (Nagata 1996, xi). Japanese civilian internees included individuals and families forcibly relocated to the Australian mainland from distant locations such as New Caledonia and the Dutch East Indies.

The No 12 camp (Figure 1), located beyond the town limits, was built for Italian POWs captured in North Africa from 1941 onwards. Though they would remain the largest group at Cowra, the camp accommodated prisoners captured across the Asia-Pacific theater, including Japanese, Formosan, Korean, and Indonesians. Japanese prisoners, starting with Australia’s first POW Toyoshima Hajime (later incarcerated at Cowra), were captured on the coast and islands off northern mainland Australia and further afield, in locations such as New Guinea and Sumatra. Cowra was chosen for the site of the prison camp due to its proximity to an established military camp (Apthorpe 2008, 10). These camps dominated life in the area during the war, with local businesses providing supplies for the camps, and the Agricultural Show Pavilion commandeered to manufacture munitions. Italian prisoners worked outside the camp on local farms, though the Japanese prisoners mainly refused to do so on the reasoning it contributed to the Allied war effort.

Figure 1: Composite image of Cowra and surrounds, in 1945 and 1954

(Aerial Photograph: 1945 – Army Information Systems Operations;

1954 – NSW Land and Property Information; composite by author).

Cowra Breakout

In 1944, there were 1,104 Japanese prisoners at Cowra. When camp authorities informed the Japanese that officers were to be separated and relocated to distant camps, they resolved to proceed with a plan to stage an escape attempt (Carr-Gregg 1978; Gordon 1978). Armed with homemade weapons fashioned from camp cutlery and equipment, prisoners rallied to the 2am bugle call from Australia’s first Japanese POW, Toyoshima, and proceeded to charge the Compound B perimeter (Gordon 1994; Figure 2). Over two hundred Japanese prisoners died by gunshot wound or suicide. Afterwards, searchers from the camps discovered prisoners who had died by self-inflicted disembowelment, after being struck by a local train, or by hanging, either within the camp’s huts or after escape (Gordon 1978). Identification of deceased prisoners was done with the assistance of Japanese prisoners, with all eventually accounted for. The exception was several prisoners incinerated in their huts, whose commingled remains were buried together (Leemon 2010, 73).

Figure 2: No. 12 Prison Camp, 1944 – Breakout location and actions

(Aerial Photograph: Army Information Systems Operations; graphics by author).

The 22nd Garrison Battalion, comprised of members of the Citizen Military Forces and responsible for guarding the No 12 camp, suffered three casualties during the escape attempt on 5 August, and one person later died from wounds. Privates Ben Hardy, Ralph Jones, and Charles Shepherd were all buried in the Cowra war cemetery. Alongside is Lieutenant Harry Doncaster from the nearby military camp who, directed to search unarmed, was killed by escaped prisoners the following day. Hardy and Jones, who died defending a guard tower and weapons placement, were later awarded the George Cross. They were considered to have died doing their duty rather than within an act of war, hence the George Cross was awarded as it was recognition of civilian heroism, as distinguished from the military award of the Victoria Cross (Blanch 2020).

Unlike Allied prisoners, Japanese prisoners had limited knowledge of capture and imprisonment within the context of the Geneva Convention (Towle et al. 2000). With military personnel guided by the Senjinkun (Field Service Code, Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors, 1941; Bullard 2006, 30–40), many Japanese service personnel provided false identities upon capture to avoid the shame of capture to their families (Moriki 1998). This unsurprisingly influenced the accuracy of records when the deceased prisoners were assessed for burial. Prisoners had sought death through the escape attempt rather than the dishonor of imprisonment, though not all prisoners elected to participate in the Breakout (Asada 1970, 87; Piper 1995, 71).

Postwar Cemetery Development

Burials were in accordance with Commonwealth commitments by the Australian government to maintain enemy graves (NAA 1947). The funeral of Hardy and Jones involved a cortege down the town’s main street accompanied by a large military march (Figure 3). In contrast, Jack Leemon reported that many of the prisoner burials occurred after dark (Leemon 2010, 68–73; Figure 4). The Cowra war cemeteries are now under the auspices of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), maintained by the local government with funds contributed by the Japanese government. The Japanese graves remained alongside those of the Australians, and Italian prisoners who had died at Cowra. The No 12 camp ceased operating in 1947 and prisoners were slowly repatriated, with the camp buildings eventually dismantled.

Figure 3: Funeral cortege of Hardy and Jones, Kendal Street Cowra, 1944.

(AWM #P01451.002).

Figure 4. Burial of Japanese prisoners at Japanese war cemetery, 1944

(AWM #073487).

During the 1950s, locals caring for graves at the Australian war cemetery decided to maintain the Japanese graves as well (Bullard 2006). In 1954, the Japanese government assumed control of the Japanese war cemetery reportedly as part of a reciprocal agreement, relating to Yokohama CWGC Cemetery in Japan (Cowra Guardian, 8 August 1994). Though the Japanese government had indicated its intention to repatriate all Japanese war dead from extraterritorial locations, those who had died in the Breakout nonetheless remained at Cowra due to potential problems in identifying them (Kobayashi and Ziino 2009, 103–15). This was in contrast with repatriation in Singapore, where war remains were sent back to Japan with living repatriates (Blackburn 2007). The consolidation of CWGC cemeteries resulting from postwar rationalization of burial sites (Beaumont 2018; Tsakanos 2021) demonstrated how cemetery populations could be transient: even in death, the bodies of service personnel were still being mobilized. This also occurred at Cowra, with the most significant change from a cemetery established out of a single conflict event to a postwar consolidation cemetery.

Diplomatic visits to the cemeteries in the 1950s and 1960s were aided by the town’s proximity to Canberra, less than 200km away. After seeing how the graves were maintained, Ambassador Suzuki Tadakatsu recommended that all Japanese wartime remains within mainland Australia be relocated to Cowra. Somewhat confusingly, the Japanese Ministry for Health and Welfare had denied the existence of prisoner graves, and prisoners of war were in fact not recognized by Japan at this time (Bullard 2006, 94), suggesting that leaving the remains in situ was simply the pragmatic solution.

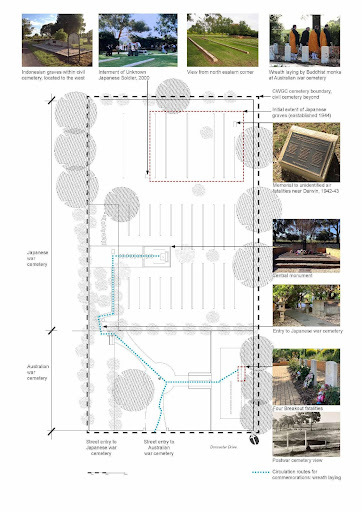

By 1963, the Australian government had approved Japan’s plan to retain and formalize the Japanese war cemetery at Cowra. Wartime remains of Japanese nationals from across the country, including combat dead, prisoners, and interned civilians, were relocated to Cowra. Building works were undertaken at the cemetery designed by Yura Shigeru, a Japanese architect then at the University of Melbourne. These included a new entry, paving and plantings, and installation of bronze name plates to graves (Yura Archive, correspondence 8 January 1963). At its center was a ceremonial area dominated by a black granite monument, with the words: “The graves of Japanese who died in the war period, September 1964.” The inclusivity in this simple statement did not distinguish service personnel from civilians, or prisoners from those involved in active combat. However, it does not recognize that some of the cemetery’s occupants were not Japanese, but originated across the Japanese empire, such as wartime Formosa (5% of overall population), Sumatra (Netherlands East Indies), and Korea, some of whom died in the Breakout. It incorporates Japanese forcibly transferred into Australia, for example from New Caledonia, and even a civilian internee that was a naturalized Australian citizen. Remains were transferred from around Australia in May 1963, over half from Barmera cemetery (South Australia), close to Loveday internment camp, and the next largest group from Tatura. The remains of 32 airmen were relocated from Berrimah cemetery in the Northern Territory. By this time, the Italian graves at Cowra had been relocated to a consolidated Italian war cemetery in Victoria, as had the Italian graves at Barmera.

In 1964, the two cemetery plots were formally separated with boundary fences and plantings. The collocated Japanese and Australian Cowra war cemeteries thus became not only a dual-nation burial location but one that was unmistakably a cemetery for combatants from opposing sides of the Asia-Pacific War: a shared burial place of former enemies. This did not go unnoticed within the town. According to newspaper reports, then-Mayor, A.J. Oliver “expressed the belief that the people of Cowra would accept the responsibility of remembering the Japanese war cemetery as a place of special significance to all Japanese people. This was especially so as the Australian war cemetery is located immediately alongside the Japanese” (Cowra Guardian, 24 November 1964). The presence of human remains held an unquestionably powerful emotional attachment for Japanese visitors (Kobayashi and Ziino 2009, 101). However, the duality of the cemetery, where a Japanese and Allied identity are intentionally presented, shrouds its multinational imperial reality.

A. J. Oliver had been involved in the care of the Japanese war cemetery, along with fellow Returned Services League (RSL) veterans who had seen active war service against Japanese forces. His sustained involvement in peace-building initiatives would later extend well beyond his civic responsibilities. Early motivation focused on changing attitudes: “A few good thinking people in the RSL had adopted the same attitude, that there was no benefit of having this absolute hatred continued. It wasn’t getting anybody anywhere and there was a gradual turning point then or a feeling in the whole Cowra community. They wanted to get rid of this idea and to treat the Japanese with some respect” (AJRP 2003, Oliver and Telfer).

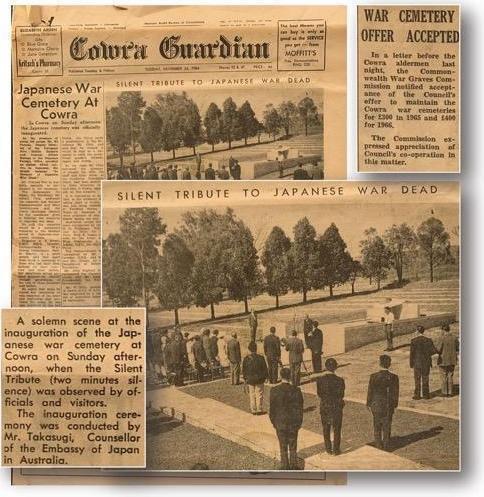

The changes at the cemetery were recognized with an inauguration ceremony in late 1964, with diplomatic attendance signifying the commencement of the site’s use for memorial diplomacy between Australia and Japan (Figure 5). However, with Japanese citizens precluded from international travel at that time (Dower 2001, 23–25), relatives were unable to visit until 1965.

Figure 5: Japanese war cemetery inauguration

(Cowra Guardian, 24 November 1964).

The ceremony included a modest Buddhist blessing arranged by the Sydney Japanese community. The event was observed contemporaneously in Japan: “It is interesting to note that, as the ceremony was taking place in Cowra, it was also being celebrated at Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo by Japanese who were prisoners of war in Cowra during the war” (Cowra Guardian, 24 November 1964; Figure 5). This sits uncomfortably with the reality that prisoners were not recognized at Yasukuni, and the prevailing wartime view that death during combat was far preferable to capture.

Figure 6: Cowra Australian and Japanese war cemeteries

(drawings and images by author).

The locations of the 247 Japanese prisoners originally buried in Cowra were largely left undisturbed by the 1964 works that resulted in the current layout (Figure 6). Changes since were the interment of an unknown Japanese soldier in 2000, whose remains had been brought back from Borneo by an Australian ex-serviceman (Cowra Guardian, 21 April 2000); and the disinterment of prisoner Wakaomi Michiaki in 2014 (Sinclair, 2015). Though Wakaomi’s death in New Guinea was reported to his family, he was interned in Australia at Gaythorne and Murchison, where he died in 1945. Unlike many of his compatriots, Wakaomi had provided his real identity when captured. Initially interred at Barmera War Cemetery, his remains were relocated to Cowra in 1964. Dr Mami Yamada recognized his name at Cowra, uncommon in their shared home prefecture of Nagano, and her enquiries resulted in Wakaomi’s family belatedly being informed of his true location. Disinterment was undertaken by an archaeologist, with partial repatriation with his family to Japan and partial reinterment at Cowra (Shinano Mainichi Shimbun, 18 September 2014). Military and civilian Japanese interments at Cowra now number 524.

The cemetery does not readily reveal the presence of others who sit outside mainstream war memory. Primary among these are the wartime graves of Indonesian prisoners who, despite having died during imprisonment in Cowra, are within the Cowra civil cemetery nearby. Interned Indonesians included merchant seamen and political prisoners who had participated in nationalist uprisings in the former Dutch East Indies. It became apparent that Australia was holding these prisoners illegally, as they were political prisoners of a foreign power rather than prisoners of war. They were released in 1944, but many had suffered in the transfer from tropical Dutch New Guinea and thirteen subsequently died in Cowra. The graves are visited annually by the Australian-Indonesian community and now recognized with a memorial by the Indonesian government (1997) and interpretive signage (2014; Apthorpe 2008). Their stories demonstrate the choice to include or exclude certain groups within the Cowra war cemeteries was subject to fluctuating geopolitical contexts in the uncertain postwar period.

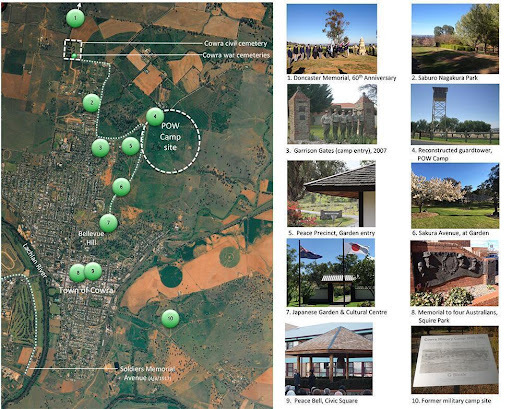

Generated by Reconciliation: Places and Events

The war cemeteries and POW camp site are the primary locations associated with the Breakout. Building on the First World War memorial landscape common to regional NSW towns, the Breakout is documented through the infrastructure of memory into a “symbolic assemblage” (Árvay et al. 2019, 132): at the POW camp site, the war cemeteries, memorials in the main street and the former camp entry known as the Garrison Gates, and with interpretive signage at the location of the wartime military camp to the east of the town, later a postwar migrant camp (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Sites of war memory within Cowra

(Aerial Photograph: NSW Land and Property Information; images by author).

The Breakout and the Cowra-Japan relationship has been the catalyst for new layers of places, events, and relationships. The town began an annual festival in 1964, the Festival of the Lachlan Valley with Japan invited as the inaugural guest nation (Treasure 1999). The festival included a series of community events culminating in an inaugural ball, decorated with Japanese motifs and both countries’ flags, and attended by Ambassador of Japan, Chiba Koh.

With Japan’s remarkable postwar economic recovery, investment in Australia increased through the 1970s, before becoming a cause for consternation during the 1980s due to fear of Japan’s emerging dominance in the Australian economy. Cowra was the recipient of such investment, which included a wool-processing plant, feed-lotting and other agricultural enterprises (Bennett 1978). These investments provided sustained employment in the area, with the wool plant operating until 2004 (AJRP 2004, Kawamata).

After the war cemeteries, the first significant built outcome representing the ongoing reconciliation relationship was opened in 1978: the Cowra Japanese Garden and Cultural Centre, funded in large part by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (Figure 8). Designed by well-known landscape architect Nakajima Takeshi (Ken) as an Edo-style strolling garden, this established a new, and derivative, site of memory. It was symbolically linked to the war cemeteries by its intention to provide a recognizably Japanese place for the souls of the deceased Japanese war dead. Later, with the establishment of the Sakura Avenue connecting the Garden, POW Camp site and war cemeteries, it was also geographically linked (Cowra Guardian, 29 July 1988; Figure 7). For key local community leader, Don Kibbler, the Garden “is a Japanese landscape […] the bones couldn’t go back to Japan, so the Japanese belief is that the bones, the spirits of those soldiers [that are buried at the Japanese War Cemetery] live in the Garden because it is recreated as a landscape of Japan” (AJRP 2003, Kibbler).

Figure 8: Cowra Japanese Garden with tea house at left,

designed by Tokyo architects Adachi Takeo and Aono Tatsushi

(photograph by author).

Each tree in Sakura Avenue is allocated to a local child and a Japanese sponsor. Acting as a seasonal link across the landscape, it traces the key landmarks of the Breakout narrative, further emphasizing the connection between the Gardens, POW Camp, and cemeteries, and again intended to act as a spiritual link between these.

Sakura Avenue is the focus of the Sakura Matsuri, hosted annually at the Garden since 1990, with the inaugural festival held in conjunction with the first NSW-Japan Sister City Conference. Cowra was soon-after selected as the site of Australia’s chapter of the World Peace Bell, installed in 1992 and further reinforcing the town’s reconciliation and peace identity.

In 2021, a new festival called Kōyō (autumn leaf color) Matsuri commenced to complement spring’s Sakura Matsuri. Both festivals hold a service of respect at the war cemeteries as part of their program of events, continuing the culture of respect for war dead and referencing the Garden’s raison d’être. Out of this continuing cultural exchange, events such as the Sakura Matsuri are able to go beyond the memory of the original event, the sadness at the loss of life and the fruitlessness of conflict, and move on to reframe the transcultural relationship between Cowra and Japan as one of shared celebration. The embedding of these festivals into the town’s calendar of events, providing a unique drawcard for its domestic and pre-Covid international tourism, also demonstrates that the original Cowra-Japan relationship has gone beyond that which Kobayashi and Ziino (2009, 112) contended when they argued that the cemeteries have not resolved the vexed issue of Japan and Australia wartime enemy history. While the staging of cross-cultural festivals does not solely prove the dissolution of wartime enmity, the continuity of Cowra-Japan relations does, evidenced in the consistent staging of annual commemorative services remembering both Allied and Japanese loss side-by-side, and the regard for this communicated through diplomatic channels. Much more challenging to quantify is the role of reconciliation participants. Ranging from the original unofficial grave custodians to local families that have billeted Japanese visitors over decades, these individuals and groups have negotiated firsthand and inherited enmity.

Figure 9: Advertisement for Sakura Matsuri, Sakura Avenue at Japanese Garden

(photograph by author).

Peace and Reconciliation Participants

Alongside the original RSL veterans like Mayor A. J. Oliver who maintained the Japanese graves, many in the Cowra community have been involved in grassroots initiatives towards reconciliation over many decades. Don Kibbler (quoted earlier), Tony Mooney, and Bob Griffiths have all been awarded the Order of the Rising Sun in recognition of their efforts (Cowra Guardian, November 2004 and 24 May 2019). All have been involved with the Cowra Japanese Garden, Don since its inception and Tony becoming involved at the critical juncture between its establishment and expansion. Bob has been a consistent leader of Cowra’s involvement in intercultural exchange, through Cowra-Seikei and Chorfarmer.

Survivors of the Breakout formed the Cowra Association (Kaura-kai) in Japan, and in Cowra, the Cowra Breakout Association represented former guards and their families, and witnesses to the event (Kobayashi and Ziino 2009). While veterans’ associations are common to military experience, for trauma management and to provide ongoing social support, prisoner groups are less common. This is even more so for Japanese veterans, where prisoners remained excluded from the war narrative. These former prisoners began to travel to Cowra and participate in commemorations alongside former guards (Levy 1984; Takahara 1987). Few participants remain but centenarian former prisoner Murakami Teruo has traveled to Cowra for several recent significant anniversaries. Though in 2012 it was reported that it may be his last visit (Cowra Guardian, 29 May 2012), he was also a central figure in commemorations in 2014 and 2019.

After Mayor A. J. Oliver traveled to Japan in 1969 to investigate options for establishing a reciprocal student exchange program, Japanese high school students also started to become part of the community and participate in commemorations. Celebrating its 50th anniversary in 2020, the result was the Cowra-Seikei Student Exchange Program. The broader “community” that has developed out of the program now numbers in the hundreds: students, teaching staff, host families in both countries, and even second-generation exchange students (Anniversary booklets 1985; 1992; 2000; 2020).

Since the early 1980s, Tokyo Agricultural University’s male choir has visited Cowra biennially (Figure 10). The Chorfarmer “Goodwill” tour travels to Australia and New Zealand, including Featherston, site of a memorial to Japanese prisoners who died there (Carr-Gregg 1978). Participants are billeted with local families. Some of the early students remain involved, with the children of original host families now hosting. Like the ever-growing Cowra-Seikei family, the Chorfarmer-Cowra community is yet another sub-group of the broader Cowra-Japan community.

Figure 10. Chorfarmer singing at Japanese war cemetery, 2014

(photograph by author).

During his address at the inaugural Kōyō Matsuri in 2021, Ambassador Yamagami Shingo named these places, events, and relationships as “milestones of the peace process between Japan and Cowra, and more broadly, Japan and Australia” (Yamagami, 4 May 2021), reflecting on the value placed on them that goes beyond Cowra. Reconciliation participants have been supported by reconciliation activities elsewhere in Asia. Nagase Takashi, active in Kanchanaburi, Thailand (Frost and Watanabe 2020), also became a visitor to Cowra due to his interest in the Breakout (Cowra Guardian, 26 July 1989; Nagase et al. 1990), as did Australian priests Fathers Tony and Paul Glynn, who have facilitated enduring links between the Japanese Buddhist community and the Cowra cemeteries (Gordon 1994, 312).

Cumulatively, these “memorial entrepreneurs” (Jordan 2006) have slowly created a transnational “imagined community” (Anderson 1983), fostered over several generations and with common purpose. The shared memory that has resulted from these many individual interactions within the community, has arguably now eclipsed the original significance of the Breakout. This has been consciously created across cultural boundaries, anchored in the spatial solemnity of the war cemeteries, and focused on the war cemeteries and the POW camp site. While the Breakout itself is now moving towards post-memory with few survivors still alive, the layers of shared memory created since are intergenerational and very much current, reflected in the longevity of commemorations at the war cemeteries and in the continuity of the cultural exchange.

Commemorative Practices

The war cemeteries sit within a broader town memorial landscape that recognizes the war participation of the local community. As so few Australian war dead were repatriated, most Australian cities and towns participate in a proxy culture of remembering without bodies, evidenced by the visual and spatial prominence of war memorials in the public domain (Inglis 1998, 258). Most noticeable are First World War memorials, where Australian casualties amounted to approximately 65% of enlistments. In excess of one hundred young men from the Cowra area died in the First World War voluntary forces. They are remembered in named form at the RSL memorial, and in monumental landscape form, as planted avenues marking two of the town’s entries (Figure 7).

Breakout anniversary commemorations on 5 August are undertaken within a progressive approach across multiple sites of memory, as the cemeteries are geographically separate from the camp site (Figure 7). This includes wreath-laying at the POW camp site, cemeteries, Garrison Gates, and usually concluding with a social gathering. The progressive nature of the commemorations results in an opportunity to consider the Breakout’s memory landscape and how memorial entrepreneurs have shaped it. Installations in the memory landscape reflect the ebb and flow of memory: Lieutenant Doncaster’s distant death location (approximately 10 km north), marked by a memorial, reflects the extent of prisoner escape, and encourages a spatial conception of the Breakout across an inhospitable winter landscape. Likewise, the guard tower reconstruction at the camp site distinguishes an otherwise unremarkable paddock in the rural landscape. Built to recognize guard participation in the Breakout, it risks the carefully built reconciliation narrative by intentionally reconstructing a building that is synonymous with war, rather than peace and reconciliation (Starr 2016).

At the war cemeteries, commemorations commence at the Australian war cemetery where wreaths are laid on the graves of the four Allied soldiers who died in the Breakout (Figure 6). The commemorative ritual of wreath laying begins at the central flagpole and proceeds up a gentle slope to the headstones at the eastern end of the cemetery plot. These are typically carried by both an Australian representative (government or community) and a Japanese representative, such as a diplomat or special interest group representative. All then proceed to the neighboring Japanese war cemetery, where a similar service is carried out. The Japanese service is officiated by a Buddhist monk on occasion, such as from the Hongwanji Buddhist Mission of Australia. Echoes of military discipline are seen in the mounting of the catafalque party, a military tradition where four members of an armed guard are arrayed around a coffin to ensure the safety of a body lying in state. The soundscape also reflects traditional Western commemorative practice with the service accompanied by a bugler performing “The Last Post” and “Reveille” in the Australian war cemetery. By contrast, that soundscape then changes to sometimes incorporate Buddhist chanting within the Japanese cemetery. These practices, though they have modified over time, sit in contrast to Saito’s view of commemoration exclusion that have prevailed elsewhere and indeed, this is demonstrated by the consistency and inclusivity of commemoration at Cowra (Saito 2017).

The design of the Japanese cemetery marked it as distinctly different from the adjacent Australian war cemetery, even though they share the same CWGC space. Given there are less graves and they are clearly visible above the ground plane, the headstone rows are the undeniable focus of the Australian cemetery. With the installation of the central monument in the Japanese cemetery, wreaths are not placed on individual graves but at the monument. This makes the focus of the Japanese cemetery the collective memory of those interred within, reinforced by the inscription in the monument memorializing all Japanese war dead within the cemetery.

Figure 11: Japanese royalty at Cowra. Clockwise from top left: Tree plaque recognizing Prince Mikasa visit, 1971;

Crown Prince Akihito and Crown Princess Michiko (from author’s collection);

Tree Plaque recognizing Prince Yoshihito visit, 1982;

Cowra Guardian, 12 January 1971 (photographs by author).

The war cemeteries have continuously hosted official and casual visits by Japanese nationals, including by sitting Prime Ministers of both Japan and Australia, reinforcing its soft power role within the Australia-Japan diplomatic, trade and regional security relationship. Japanese royalty, Prince Mikasa (brother of Showa Emperor), officially visited as early as 1971, followed by then-Crown Prince Akihito and Crown Princess Michiko in 1973 (Kobayashi and Ziino 2009, 109–110; Figure 11). The event and the cemeteries remain relatively unknown in Japan (Kobayashi and Ziino 2009, 111), despite efforts by grassroots organizations as the POW Research Network and Kobe Japan-Australia Society, and in Cowra’s friendship agreement with Jōetsu city (site of former POW camp, Niigata Prefecture).

War Cemetery as Reconciliation Landscape

War cemeteries can be viewed as sites of memory that continue to resonate with visitors long after their establishment. The Cowra cemetery spaces have acted as stages to provide a setting for transcultural commemorative engagement, activated on specific occasions by participants that lead or contributed, or simply act as witness to the commemorative process, and supported by the places and relationships that have resulted from the Cowra-Japan relationship. Recent research has produced a bilingual online database of the Japanese war cemetery occupants, co-ordinating previously inaccessible information into a searchable digital format (https://www.cowrajapanesecemetery.org/). Notably, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission online record lists occupancy information for the Allied graves only.

The presence of enemy war dead remained an uncomfortable reality in the postwar period when Australians were still coming to terms with the horror of testimony presented in war crimes trials (Fitzpatrick et al. 2016). Gavan McCormack (2021) illuminates further complications to this postwar binary with his exploration of Korean conscript culpability, framed with proximity to survivor testimony. The reality of non-Japanese imperial subjects dying in the Breakout undermines this liminality between being a colonial subject and their place in the empire, demonstrating they were ultimately denied recognition of their true identity. The welcoming of Japanese nationals was therefore remarkable as many of Cowra’s civic leaders had been Second World War veterans and, under their care, the Japanese graves were maintained (Gordon 1994; AJRP 2003, Bennett; AJRP 2003, Oliver and Telfer). To explain this, Lachlan Grant argues that Allied veteran attitudes towards Japan have been moderated by experiences such as contact with Japanese civilians as prisoners, participation in the postwar occupation of Japan, and empathy with suffering of the Japanese civilian population (Grant 2015: 231–235). This view is corroborated in the Cowra experience with Alf Cowley explaining that “usually the non-combatants are the people that have hostility, not the genuine ex-servicemen” (AJRP 2003, Telfer and Cowley; Figure 12).

Figure 12: Cowra Guardian, 26 November 1965.

These attitudes ultimately set the Cowra war cemeteries on a trajectory to its current identity as a place of peace and reconciliation. The war cemeteries have played a central role, principally through their shared hosting of war dead in a common location and their sustained use carrying out the rituals of war commemoration. Accompanied by the reverence accorded the corporeal reality of war loss, and therefore unlike acts of reconciliation proffered at war memorials, the Cowra war cemeteries provide a template for a modest scale of grassroots reconciliation.

Conclusion

The escape attempt at Cowra was arguably the largest wartime prison break in history and the only land engagement on the Australian mainland during the Asia-Pacific War (Bullard 2006, 48). With the war dead from the incident in a single location, the breadth of the incident and its unusual war memory nature is easier to comprehend. Not only does it host former enemy combatants within the same bordered location, but the occupants demonstrate the duality of active and inactive (prisoner) military service, alongside the civilians that represented the wartime enemy within Australia’s borders. It is this plurality of occupants, anchored by their archaeological presence in adjacent war cemeteries that distinguishes the Cowra war cemeteries as singular.

The 1964 cemetery works have supported this. While the cemeteries initially represented the collective war dead of a single nation from a specific conflict, the 1964 consolidation meant that the war cemeteries became representative locations for each country within the same cemetery: not the whole war, but rather representing a specific facet of the Asia-Pacific War (being all Japanese wartime remains) in a single extraterritorial location with a dedicated purpose (of mourning and commemoration). While the Cowra story has been marginalized within the larger Asia-Pacific War geopolitical discourse, it has nonetheless played a valued role in bilateral relations. The presence of Japanese prisoner remains serves the important purpose of teaching about lesser-known prisoner narratives. Unlike the records of Allied POWs at Ryōzen Kannon in Kyoto (see the contribution of Milne and Moreton in this special issue), the Breakout narrative has maintained its longevity due to its relevance to the population of Cowra and the consistent involvement of the “imagined community” (Anderson 1983) that has evolved from the many layers of reconciliation places, events, and relationships.

It is through a narrowed lens of history that the town of Cowra has engaged with Japan: an edited version that comprises royalty, diplomats, Breakout participants, and reconciliation activists that have responded to the overtures extended by the town’s leaders and the local community. Likewise, the cemeteries offer an edited version: of the Breakout (Indonesian graves spatially separate); Cowra’s prisoner history (Italian graves relocated); and of the Cowra-Japan relationship. Of the latter, there are visual and oral history records to remind us that the meeting of former enemy nations was indeed awkward, there were cultural miscommunications, but individuals and groups persevered.

The Breakout story since the war is one of fairly ordinary interactions that have cumulatively become part of the Cowra community, consistent with Yasuko Claremont’s view that the power of grassroots reconciliation activities lies in “making contact and creating friendships on a personal level” (Claremont 2017). The places, events and relationships that have been generated to further the reconciliation process has now created a shared history of Cowra and Japan that has gone beyond the Breakout as its origin. At its center, the war cemeteries have remained a continuous presence, hosting rituals of war loss commemoration over successive generations. At the intersection of national, community and personal memories of the Second World War and the Breakout, the emotional and geographical connections can be seen through the continuity of rituals of remembrance, negotiated within the postwar climate of lingering hostility and slowly transforming to a shared and collective transcultural memory.

References

Allen, Matthew and Sakamoto, Rumi. 2013. “War and Peace: War Memories and Museums in Japan.” History Compass, 11 (12): 1047–1058.

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Árvay, Anett and Foote, Kenneth. 2021. “The Spatiality of Memoryscape, Public Memory, Commemoration.” In Sarah de Nardi, Hilary Orange, Steven High, and Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto (eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Memory and Place. Abingdon: Routledge, 129–137.

Asada, Teruhiko. 1970. Translated by Ray Cowan. The Night of a Thousand Suicides. North Ryde: Angus and Robertson.

Ashplant, T. G., Dawson, Graham, and Roper, Michael. 2000. “The Politics of War Memory and Commemoration: Contexts, Structures, and Dynamics.” In T.G. Ashplant, Graham Dawson, and Michael Roper (eds.) The Politics of War Memory and Commemoration. London: Routledge, 3–86.

Apthorpe, G. 2008. A Town at War: Stories from Cowra during WWII. Elizabeth SA: Railmac Publications.

AJRP (Australia Japan Research Project). 2003–2004. “Cowra Japan Conversations”: Barbara Bennett (AWM S03080); Chris Kawamata and Steve Kawamata (2004; AWM S03339); Don Kibbler (2003; AWM S03078); Keith Telfer and Alf Cowley (2003; AWM S03075); A.J. Oliver and Keith Telfer (2003: AWM S03072). [Accessed 2 July 2014].

Beaumont, Joan. 2005. “Prisoners of War in Australian National Memory.” In Bob Moore and Barbara Hately-Broad (eds.) Prisoners of War, Prisoners of Peace: Captivity, Homecoming, and Memory in World War Two. New York: Berg, 185–194.

Beaumont, Joan. 2018. “The Yokohama War Cemetery, Japan: Imperial, National and Local Remembrance.” In Patrick Finney (ed.) Remembering the Second World War. London: Routledge, 158–174.

Bennett, Barbara. 1978. “Cowra: A Special Link Between Australia and Japan.” Armidale and District Historical Society Journal and Proceedings, No. 21. Armidale: Armidale and District Historical Society.

Blackburn, Kevin. 2007. “Heritage Site, War Memorial and Tourist Stop: The Japanese Cemetery of Singapore, 1891–2005.” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 80 (1): 17–39.

Blanch, Craig. 2020. For Gallantry: Australians Awarded the George Cross & the Cross of Valour. Sydney: New South Books.

Bullard, Steve. 2006. Translated by Keiko Tamura. Blankets on the Wire: The Cowra Breakout and its Aftermath. Canberra: Australian War Memorial.

Carr-Gregg, Charlotte. 1978. Japanese Prisoners of War in Revolt. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Claremont, Yasuko. 2017. Citizen Power: Postwar Reconciliation. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Clarke, Hugh. 1965. Escape to Death: The Japanese Break-out at Cowra, 1944. Sydney: Random House.

Coe, Mary. 1986. Windradyne: A Wiradjuri Koorie. Sydney: Blackbooks.

Cowra Guardian newspaper, various dates listed, 1965–2019.

Dower, John. 2000. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York: Norton.

Fitzpatrick, Georgina, McCormack, Tim, and Morris, Narrelle. 2016. Australia’s War Crimes Trials 1945–51. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff.

Foucault, Michel. 1986. “Of Other Spaces.” Diacritics 16 (1): 22–27.

Frost, Mark and Watanabe, Yosuke. 2020. “Methods of Reconciliation: The ‘Rich Tradition’ of Japanese War Memory Activism in Post-war Southeast Asia.” In Mark R. Frost, Edward Vickers, and Daniel Schumacher (eds.) Remembering Asia’s World War Two. London: Routledge, 247–277.

Fujitani, Takashi, White, Geoffrey M., and Yoneyama, Lisa (eds.). 2001. Perilous Memories: The Asia-Pacific War(s). Durham: Duke University Press.

Gordon, Harry. 1978. Die Like the Carp. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Gordon, Harry. 1994. Voyage from Shame: The Cowra Breakout and Afterwards. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Grant, Lachlan. 2015. Australian Soldiers in the Asia-Pacific in World War II. Sydney: NewSouth Publishing.

Graves, Mathew. 2014. “Memorial Diplomacy in Franco-Australian Relations”. In Shanti Sumartojo and Ben Wellings (eds.) Nation, Memory and Great War Commemoration: Mobilizing the Past in Europe, Australia and New Zealand. Bern: Peter Lang, 169–187.

Heiss, Anita. 2016. Barbed Wire and Cherry Blossoms. Sydney: Simon & Schuster.

Herborn, Peter, and Hutchinson, Frances. 2014. “‘Landscapes of Remembrance’ and Sites of Conscience” Exploring Ways of Learning Beyond Militarising ‘Maps’ and the Future.” Journal for Peace Education, 11, (2): 131–149.

Hirsch, Marianne. 2012. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press.

Igarashi, Yoshikuni. 2000. Bodies of Memory: Narratives of War in Postwar Japanese Culture, 1945–1970. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Inglis, Ken. 1998. Sacred Spaces: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Jordan, Jennifer A. 2006. “Memorial Projects as Sites of Social Integration in Post–1989 Berlin?” German Politics & Society 24 (4) (81): 77–94.

Keneally, Tom. 2013. Shame and the Captives. North Sydney: Random House.

Kobayashi, Ai and Ziino, Bart. 2009. “Cowra Japanese War Cemetery.” In William Logan and Keir Reeves (eds.) Places of Pain and Shame: Dealing with “Difficult Heritage.” Routledge, Abingdon, 99–113.

Leemon, Jack, Leemon, Betsy, and Morgan, Catherine. 2010. War Graves Digger: Service with an Australian War Graves Registration Unit. Loftus: Australian Military History Publications.

Levy, Curtis (Dir.). 1984. Breakout (documentary). Olsen Levy Productions.

McCormack, Gavan, and Nelson, Hank (eds.). 1993. The Burma–Thailand Railway: Memory and History. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

McCormack, Gavan. 2021. “Yi Hak-nae and the Burma-Thailand Railway.” The Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 19 (15: 1). (https://apjjf.org/2021/15/McCormack.html)

Mackenzie, Kenneth Seaforth. 1951. Dead Men Rising. London: Jonathan Cape Ltd.

Moriki, Masahiro. 1998. Translated by Midori Treeve. Cowra Uprising: One Survivor’s Memoir. Sydney: Random House.

Nagase Takashi and Yoshida, Akira. 1990. Kaura nihonhei horyo shūyōjo [Cowra Japanese Soldier POW Camp]. Tokyo: Aoki Shoten.

Nagata Yuriko. 1996. Unwanted Aliens. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

National Archives of Australia. NAA CWGC 1/2/1/57. “Enemy Graves in Civil Cemeteries and Enemy War Graves in the Pacific Area”.

Pieris, Anoma. 2014. “Cowra, NSW: Architectures of Internment.” Translation: Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand 31: 785–796.

Pieris, Anoma and Horiuchi, Lynne. 2017. “Temporal Cities: Commemorations at Manzanar, California and Cowra, Australia.” Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures and the Americas 3: 292–321.

Piper, Robert. 1995. The Hidden Chapters Untold Stories of Australians at War in the Pacific. Carlton: Pagemasters.

Rechniewski, Elizabeth. 2012. “The Memorial Path from Darwin to Cowra”. Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia, 44: 48–64.

Rikugun-Shō. 1941. Senjinkun / Rikugun-Shō (Field Service Code). English translation by Tokyo Gazette Publishing House. Tokyo: Tokyo Gazette Publishing House. The Internet Archive [Accessed 9 September 2021].

Saaler, Sven, and Schwentker, Wolfgang (eds.). 2008. The Power of Memory in Modern Japan. Folkestone: Global Oriental.

Saito Hiro. 2017. “The History Problem: The Politics of War Commemoration in East Asia.” The Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Vol. 15, Issue 5, No. 4.

Sakate Yoji (director). 2014. Kaura no honchō kaigi [Honchos Meeting in Cowra]. Play and performance.

Scates, Bruce. 2013. Anzac Journeys: Returning to the Battlefields of World War Two. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Seaton, Philip A. 2007. Japan’s Contested War Memories: The “Memory Rifts” in Historical Consciousness of World War II. London: Routledge.

Seikei High School: Cowra Seikei Anniversary booklets. 1985, 1992, 2000, 2020. Tokyo.

Sharpley, Richard. 2020. “‘Kamikaze’ Heritage Tourism in Japan: A Pathway to Peace and Understanding?” Journal of Heritage Tourism, 15 (6): 709–726.

Sheftall, M. G. 2008. “Tokkō Zaidan: A Case Study of Institutional Japanese War Memorialisation.” In Sven Saaler and Wolfgang Schwentker (eds.) The Power of Memory in Modern Japan. Folkestone: Global Oriental, 54–77.

Sinclair, Hannah. 2015. “Japanese Prisoner of War’s Ashes Recovered in Historic, Emotional Repatriation.” SBS News, 12 September. [Accessed 9 September 2021].

Starr, Alison. 2016. “Traces of Memory: Australian-Japanese Reconciliation in a Post-war Cowra Landscape.” Historic Environment 28 (3): 74–85.

Stellmach, Barbara. 1994. “Blood Yellow.” Manuscript to a play.

Takahara Marekuni. 1987. Kaura monogatari [The Story of Cowra]. Kobe: Tōyō Keizai Shinposha.

Towle, Philip, Kosuge, Margaret, and Kibata, Yoichi (eds.). 2000. Japanese Prisoners of War. New York: Hambledon and London.

Trefalt, Beatrice. 2015. “The Endless Search for Dead Men.” In Christina Twomey and Ernest Koh (eds.) The Pacific War: Aftermaths, Remembrance and Culture. London: Routledge, 270–281.

Treasure, Cyril (ed.). 1999. Cowra’s Festival of the Lachlan Valley. Cowra.

Tsakonas, Athanasios. 2021. In Honour of War Heroes: Colin St Clair Oakes and the Design of Kranji War Memorial. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International (Asia).

Twomey, Christina. 2018. The Battle Within: POWs in Postwar Australia. Sydney: NewSouth Books.

Weatherburn, A. K. 2006. “Evans, George William (1780–1852).” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Published first in hardcopy 1966 [Accessed 14 March 2021].

Winter, Jay. 1995. Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yamada Mami. 2014. “Kaurajiken (1944-nen) no kenkyū ― horyo no hibi o ikita nipponhei-tachi no ‘nichijō’ kara no sai kōsatsu.” [Reconsidering the Cowra Breakout of 1944: From the Viewpoints of Survived Japanese Prisoners of War and Their “Everyday Lives” in the Camp]. Unpublished doctoral thesis (English language publication forthcoming). Ochanomizu University, Japan.

Yamagami Shingo. 4 May 2021. Speech at Inaugural Kōyō Matsuri, Cowra Japanese Gardens.

Yura Shigeru. 1963–65. Cowra Japanese War Cemetery 1963–5. Untitled archival collection held at Cowra Council.