Abstract: Today, it is customary to describe the Japanese archipelago in terms of the neutral distinction between the Sea of Japan side (Nihonkai-gawa) and the Pacific Ocean side (Taiheiyō-gawa). For much of the 20th century, however, these regions were called respectively ura Nihon and omote Nihon, or roughly “the Backside of Japan” and “the Frontside of Japan.” This continued until the 1960s when the terms were criticized as discriminatory and their usage terminated. How, then, did the Sea of Japan coastal region come to be known by the discriminatory term “the Backside”? Intrigued by this question, this paper retraces the little-studied history of the place name ura Nihon. As I will show, behind the place name ura Nihon are forgotten histories not just of uneven domestic economic development but also colonial expansion and empire building in Northeast Asia. That is, ura Nihon is both a history of the Japanese nation and of the empire. By retelling this history, the paper seeks to contribute to understanding the ways in which empire building in Northeast Asia was connected to the domestic history of the Japanese nation-state in the 20th century.

Keywords: Backside of Japan, Frontside of Japan, geography, development, empire, the Sea of Japan, Russo-Japanese War, imperial autarky, Cold War

Introduction

Today, it is customary to describe the Japanese archipelago in terms of the distinction between the Sea of Japan side (Nihonkai-gawa) and the Pacific Ocean side (Taiheiyō-gawa). These two terms are descriptive and objective. One term does not require the other to be meaningful. For the larger part of the twentieth century, however, the regions referred to by these terms were called respectively ura Nihon and omote Nihon, or roughly “the Backside of Japan” and “the Frontside of Japan.” It is easy to see that the two terms are interdependent, that is, one would not make sense without the other, and furthermore they indicate an unequal relationship, insinuating backwardness for the Sea of Japan side in contrast to the Pacific Ocean side. Indeed, the two terms stopped being used in the 1960s precisely because ura Nihon (“the Backside of Japan”) was criticized as discriminatory. How, then, did the Sea of Japan coastal region come to be called the “Backside” and how did the term gain a discriminatory nuance? This paper answers these questions by retracing the little-studied history of the place name ura Nihon. It shows that behind the neutral geography names “the Sea of Japan side” and “the Pacific Ocean side” are forgotten histories not just of uneven domestic economic development but also colonial expansion and empire-building in Northeast Asia. By retelling this history, the paper seeks to contribute to our understanding of the ways in which empire building in Northeast Asia was interconnected to the domestic history of the Japanese nation-state in the twentieth century.

|

Two major studies in Japanese took up the topic of ura Nihon. Abe Tsunehisa (1997) and Furumaya Tadao (1997) focus on examining ura-Nihon as a history of peripheral formation and regional inequality in Japan’s modernization. Abe traces in detail the development of industrial, educational, and military institutions in the Meiji period which prioritized the Pacific Ocean side. This resulted in population flow from the Sea of Japan side to the Pacific region and the transformation of the former into a periphery in the modernizing – and centralizing – nation-state. Furumaya examines the process of geographical, economic and cultural differentiation of ura Nihon and omote Nihon from the beginning of the twentieth century to the 1970s, and argues that ura Nihon and omote Nihon represent an interdependent, unequal relationship inherent in modern capitalist development. Different from these studies of ura Nihon as domestic history, Yoshii Kenichi (2000) situates the ura Nihon area of Japan in the broader Sea of Japan rim region and explores the connections between ura Nihon and other parts of the rim region, especially Korea and Manchuria, during Japanese imperialist expansions on the continent in the first half of the twentieth century. While empirically informative and suggestive, these studies raised more questions than answers. One of the questions is how to understand the ideological significance of ura Nihon as a spatial term in relation to empire-building. That is, how to understand the historical relation between spatial imagination and place making on the one hand and imperialist motives of capitalist development and territorial expansion on the other? This paper is the first step in answering this large question.

The term ura Nihon originated out of late Meiji period (1868-1912) modernization for designating the Sea of Japan side as a region of relative underdevelopment in comparison to the modernizing Pacific Ocean side, or omote Nihon (Furumaya 1998). During the Russo-Japanese War (1904-5), the place name ura Nihon evolved into an ideological discourse of development and colonial expansion. This conception identified the Backside region, in its spatial proximity and cultural association with the Asian continent, as climatically bleak, culturally backward, and economically stagnant in contradistinction to the bright progressive frontside embodying Japan’s modernity. As such, ura Nihon connect Japan, to Asia’s Backside, notably China, Russia and Korea at a time when the military, business, politicians, and intellectuals competed to modernize the Backside region by devising arguments for expanding trade, transportation, immigration, and colonial development toward the continent (Yoshii 2000).

The ura Nihon-vs.-omote Nihon distinction then not only reified the unequal relationship within the Japanese archipelago but helped encode inequality and discrimination in nation-state building into imperial projects of spatial territorialization, military expansion and economic development. Into the 1930s-40s, transformation of the Backside became part of the ambitious plan for the construction of an imperial autarkic economy in Northeast Asia, with the ura Nihon region eventually becoming the “Frontside” connecting the Japanese metropole with its Asian colonies (Yoshii 2000). After 1945, however, the collapse of the empire reduced the Backside to a domestic problem, and United States dominance of Northeast Asia rendered the Sea of Japan coastal region directly confronting a hostile communist continent, into a periphery again. At the same time, a rapidly developing Japan looked across the Pacific to the U.S. for security, economic support, and a new vision of progress and power. Despite the fact that ura Nihon was replaced by the neutrally sounding term “Sea of Japan side” in the 1960s (Furumaya 1997, 7), the continuing peripheral status of the region today remains a constant reminder of legacies of empires in contemporary Northeast Asia.

The Birth of Ura Nihon, 1866-1904

The origins of the pair concept of ura Nihon and omote Nihon can be traced to the formation of modern geology and geography in Meiji Japan. Geology and geography offered new methods for classifying and explaining physical space in the midst of modern transformations. In the 1860s, American geologist Richard Pumpelly was invited by the Tokugawa shogunate to conduct geological investigations in Japan and the Qing government in China later commissioned him to explore coal mines. Combining his investigation results in the two countries, Pumpelly identified a NE-SW-trending system of tectonic elevation and depression that governed the geomorphic configuration of East Asia, which he would later expand to the Northern Hemisphere worldwide. He named this “the Sinian system” (Pumpelly 1866). The Sinian interpretive framework reshaped subsequent geographic understanding of Japan.

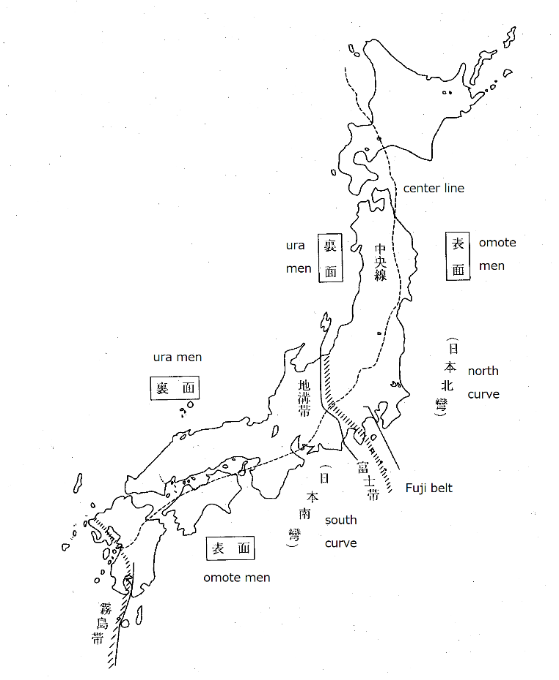

The framework helped Japanese geologists in the 1880s locate the Japanese archipelago in the spatial context of the Asian continent and the Pacific Ocean to understand Japan’s geology. Dr. Harada Toyokichi, director of the geological bureau of the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, played the key role in developing a geological theory for Japan based on Pumpelly’s Sinian system. He developed the theory in his report On the Geological Structure of Japan (Harada 1888). Harada modelled Japan’s mountainous topography as divided into a front/convex side (omote-men 表面) (facing the Pacific Ocean) and a back/concave side (ura-men 裏面) (facing the Sea of Japan and the Asian continent) along the NE-SW axis identified by Pumpelly. Harada explains, “mountain systems of the world all share certain regularity: they come in curved shape, forming a concave side and a convex side. They are known respectively in geological terms as ‘inner side’ or ura-men, and ‘outer side’ or omote-men” (Harada 1888, 321). He then situates Japan in relation to the Asian continent, describing the “empire of Japan” in the shape of a half circle surrounding the southeastern part of the Asian continent. This bow-liked half circle consists of a series of curved mountain ranges that connect with two mountain systems, the Sinian system that starts from the Himalayan range in the southwest, and the Karafuto system extending southwest from the Kamchatka Peninsula (Harada 1888, 310-312).

To facilitate understanding of Japan’s geological structure, Harada further proposes a virtual center line running through the archipelago to foreground its curved shape. With the center line, Harada divides the archipelago into five parts: first is the pair of the north curve and south curve, and then each curve is divided by the center line into outer side and inner side. The fifth part is the massive fault when the two mountain systems meet, i.e., the “Fuji belt” (see map below). This five-part interpretive framework turned out to be very useful for illustrating the earth surface, which differs drastically on the two sides of the central line, one side facing the Pacific, the other Sea of Japan. Soon, this interpretive framework, in particular the geological distinction of ura and omote, were adopted by geographers and school teachers to formulate modern geography for middle school education.

Underlying modern geography was the dominant discourse of Civilization (bunmei) and progress popularized in post-Restoration Japan. Civilization discourse used the distinctions of civilization vs. barbarism and progress vs. stagnation to create a hierarchical understanding of the world, manifested by the Meiji intellectual Fukuzawa Yukichi’s slogan “Leaving Asia (& Joining Europe)” in 1885. Here, “Asia” and “the West” were objectified as spatial representations of stagnation and barbarism on the one hand and civilization and progress on the other. Spatialization of these contrasting values helped Meiji intellectuals situate Japan in the civilizing and modernizing world in the late nineteenth century. This hierarchical conception of modern geography was in turn taught to elementary and middle school students. One of the most widely used geography primer textbooks was Fukuzawa’s kuni-zukushi, or “All the Countries in the World,” which ranked the countries according to levels of civilization and progress (Fukuzawa 1869).

In this way, geography and Civilization layed the groundwork for the emergence of modern nationalism in 1890s Japan, reinforced by Japan’s success in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). Accompanying the rise of Meiji nationalism was a process of restructuring space, i.e., the formation of a geo-body shaped by self-other relationships between a stagnant Asia and a progressive West. In the process, the neutral geographical distinction of ura/Backside and omote/Frontside changed to ura Nihon and omote Nihon, which came to be seen as parts of a single, synergistic whole, two compatible yet hierarchical parts of the geo-body of Japan. Formation of the ura Nihon-vs.-omote Nihon distinction as parts of the geo-body of Japan unfolded in tandem with rapid construction of a centralized socio-political order during the mid-Meiji decades, when railway construction, military installations, and establishment of a national education system transformed the natural and cultural spaces of the archipelago. Railway projects particularly helped turn the Pacific coast into a magnet for industry, commerce, and population concentration (Oikawa 2014, Abe 1997). This Pacific coast spatial transformation made the rest of the country appear less progressive and peripheral.

By the 1890s, the previously neutral ura Nihon-vs. omote Nihon geographical distinction, respectively referring to the Sea of Japan side and the Pacific Ocean side, had begun to be used to represent differences not only in economic development but in cultural and civilizational levels as well. Geographical distinction had changed to cultural hierarchy, which highlighted the contrast between a maritime and progressive Japan – omote Nihon (Frontside of Japan) – and a continentally connected, culturally backward Japan – ura Nihon (Backside of Japan). The Meiji-period journalist Tsukakoshi Yoshitarō’s book Chiri to jinji (“Geography and Human Affairs”) (1901) exemplifies this culturalization of a geographical distinction.

Tsukakoshi explained how climate influenced the national character of the Japanese which for him was of two varieties: maritime and continental, coinciding spatially with the Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Japan regions, i.e., omote Nihon and ura Nihon. He began by comparing the climate of the two regions. Under the strong influence of wind and air pressure from the continent, ura Nihon has more precipitation especially snow in winter, more cloudy days, and lower average temperature than omote Nihon (Tsukakoshi 1901, 5-16). These climatic differences shaped different national characters of the two regions. “Cold weather in ura Nihon turns people into monotonous and cowering beings. Cloudy weather slows people’s sensitivities and makes them torpid. …People become passive and lack the will to go out and conquer” (Tsukakoshi 1901, 17-20). He calls this type of Japanese national character “continental” and contrasts it with the “maritime Japan” of omote Nihon. “Warm and dry weather in maritime Japan warms people’s blood …They are positive and optimistic, ready to challenge and conquer. Disliking monotony, people are poetic, excelling at arts, music, and philosophy” (Tsukakoshi 1901, 23-24). Indeed, “as yet no continental Japanese have conquered and ruled this country. This has to do with geographical disadvantages but the climate and people’s character also have to be blamed” (Tsukakoshi 1901, 26-27).

The Emergence of the Ura Nihon Ideology, 1904-1918

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, a key episode in the history of imperial rivalry in Northeast Asia, provided the impetus for the expansion of ura Nihon into an ideology of economic development and colonial expansion. The costly war was sustained in Japan by an expansive anti-Russian nationalism which drew the gaze of the nation across the Sea of Japan to the continent, particularly Korea, China and Russia. From before the outbreak of the war, anti-Russian nationalism provoked a continental expansionism that encompassed the entire Russian Far East. Representative of this popular nationalism was the so-called “Seven Doctors of the Russo-Japanese War,” a group of university professors who argued for annexation of Siberia, all the way to Lake Baikal. Leading the Seven Doctors group was Tomizu Hirondo, law professor of Tokyo Imperial University, also known as Prof. Baikal for his hardline argument for Siberian annexation. During the War, opinion leaders such as the Seven Doctors projected Japan’s decisive victory resulting in indemnity and territorial acquisitions as war prizes. When the government concluded a peace treaty with Russia without gaining an indemnity or much territory, in September 1905 people rallied in Hibiya Park in Tokyo to protest again the peace treaty. When the police intervened, a riot occurred.

Anti-Russian nationalism reinforced by the Hibiya Riot turned ura Nihon into a popular ideological force. Formulated by politicians, lawyers, journalists, and activists from the ura Nihon region, including leaders of the Hibiya Riot, as well as such prominent figures as Tokyo Imperial University maritime law professor Matsunami Niichirō, this discourse politicized the relative underdevelopment of the region as discriminatory and advocated linking ura Nihon to trade with and colonization of the continent so as to lift the region out of underdevelopment. His connection of ura Nihon with the continent was facilitated by Matsunami’s view of the Sea of Japan as Japan’s territorial waters. Matsunami elaborated on imperialist expansion qua economic development in the nationalist journal Tōhoku hyōron in March 1906:

The Sea of Japan coastal region has long been called ura Nihon. Its progress cannot be compared to the Pacific Ocean coastal region. Its agriculture is still primitive; its industry has only habotai silk; fishing remains primitive and maritime navigation can in no way rival the complex networks of omote Nihon. …Worst of all, railway transportation in ura Nihon is least developed. In other words, the region facing the Sea of Japan has been treated like a stepchild of the country. …Will ura Nihon remain asleep forever? Will Japan always remain in a state of paralysis on one side? Although …people in ura Nihon today lack the confidence to compete for national political power, this deficiency is not innate. We can expect them to find ways to develop. …The Sea of Japan rim region is rich in both maritime and land products, whose cultivation will bring enormous wealth. Now that most of the region has become Japanese territory, …it is the responsibility of we Japanese to not be satisfied with merely maritime gains but proceed to the continent to develop the rich resources there. …The future of the Sea of Japan is promising as essentially it has become the territorial waters of Japan. …It is known by name as Japan’s territorial waters and is directly related to the empire of Japan (Matsunami 1906, 12-13).

The ura Nihon ideology dovetailed well with local initiatives in infrastructure building in the Sea of Japan coastal region and colonial developments on the continent. In the 1900s, major cities of Niigata, Tsuruga, and Fushiki (伏木) on the Sea of Japan coast spearheaded initiatives in infrastructure building, primarily harbor dredging and expansion, and competed to open trade with Vladivostok in anticipation of profit through the Trans-Siberia Railway which was completed in June 1904 (Yoshii 2000). They also campaigned for central government financial support through Diet politics.

The ura Nihon ideology was soon incorporated into projects of colonial development in the continent. Gaining control of the South Manchurian Railway, a key prize of the Russo-Japanese War, spurred four decades of vigorous business expansion and military planning designed to turn Manchuria into a periphery both of the Japanese metropole in general and of Backside Japan in particular (Yoshii 2000, Matsusaka 2001). Central to business and military planning was railway construction. The Kwantung Army on security grounds (i.e., the need to mobilize against possible Russian attack), and the South Manchurian Railway Company (SMR) for political reasons (to prevent Chinese encirclement) from 1906 began planning to build a second major railway line that connected Changchun, the northern terminal of the south Manchuria railway, with northern coastal Korea and then the backside of Japan (Inoue 1990). The Korean colonial government also promoted this railway to help bring the Korean-Chinese borderland region (today’s Yanbian region of China neighboring North Korea) under control. Strategic and political motives were reinforced by busines interests. Into the 1910s, Japanese traders in Chongjin, a port on the northern coast newly opened by the colonial government in Korea, joined local chambers of commerce in Japan to campaign to support open maritime transportation across the Sea of Japan, which they argued would contribute to development of both ura Nihon and Korea. Opening the maritime route in 1917 and simultaneous completion of the railway connecting central Korea with the Korean-Chinese borderland region led to escalating competition between transportation businesses in Japan and those in colonial Korea.

Competing Ideologies of Ura Nihon, 1918-1931

The Russian Revolution (1917-1923), which promoted national self-determination as the principle for oppressed nations to achieve liberation from imperialism and the League of Nations’ adoption of Woodrow Wilson’s national self-determination principles in the wake of WWI, helped consolidate the nation-state world system and delegitimize imperialism. As direct colonization fell out of fashion, imperialism started to promote the new legitimizing logic of development. At the same time, global circulation of the national self-determination principle and conciliatory international politics fostered an ideological environment favoring democracy. The evolution of the ura Nihon ideology during 1918-1931 is a dual story of cultural politics of “Taisho Democracy” and transformation of local protests against uneven economic development into colonial endeavors in the continent.

The ura Nihon perspective bifurcated into two competing stances for connecting with the continent across the Sea of Japan to shape regional development. On the one hand, an anti-Soviet, pro-expansion colonial discourse still dominated Japanese public discussion which promoted developing ura Nihon by transforming it into the empire’s Frontside to spearhead colonization and trade with Korea, Manchuria and Mongolia. This approach emphasized the harbors of Chongjin and Rajin in Korea as terminal stations for the northern railway line connecting ura Nihon to the resource-rich continent. On the other hand, amidst the predominantly pro-intervention public opinion, a number of journalists, political activists, business leaders, and scholars in Japan, Korea and Vladivostok opposed sending troops to Siberia during the Siberian Expedition of 1918-22 and advocated mutual support and joint development in the Sea of Japan rim (Furumaya 1997, 116-120, Yoshii 2000, 140-162, Matsuo 1922). They understood the Rice Riots (米騒動) of 1918, which started in Uozu, Toyama Prefecture, of the ura Nihon region and spread throughout the country, as a manifestation of Japan’s food shortage problem as well as regional disparity inherent in its development. Through the 1920s, they proposed improving ura Nihon and solving the rice problem by cooperating with Chinese, Koreans and Russians based on a conception of national self-determination of Asian peoples. They called for joint Chinese, Korean, Russian and Japanese development of the Tomangan (Toman River, Ch. Tumenjiang, 豆満江) region. The Toman River runs between Manchuria, Russia and Korea. A group of journalists, local politicians, and business leaders from ura Nihon, seeing the region’s link with the continent as vital for its development, was instrumental in persuading the Japanese government to recognize and establish diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union (Yoshii 2000, 145-147).

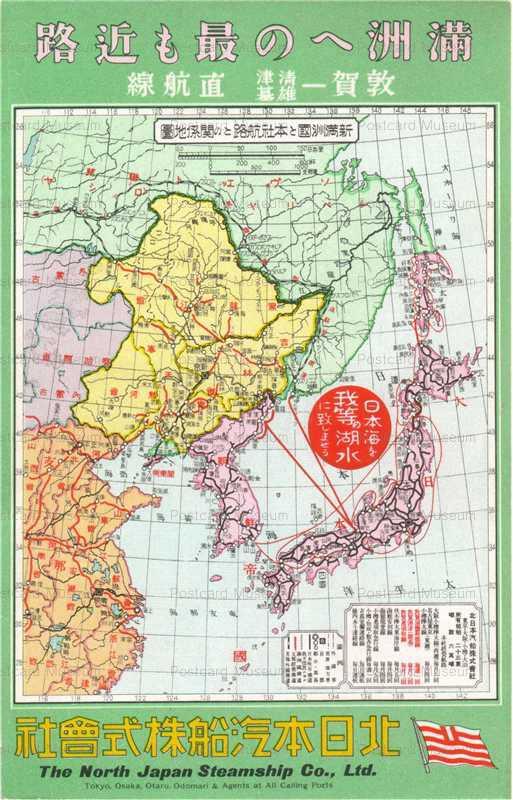

The rice riots of 1918 also foregrounded the reality that residents of major rice producing areas could not afford rice due to sky-rocketing prices. The rice riots contributed to the transformation of ura Nihon into a regional identity based on a sense of being sacrificed for economic development in the Frontside region. As this regional identity gained traction, local governments and businesses in Tsuruga, Niigata and other ura Nihon port cities from 1918 competed to open maritime routes with colonial Korea. Significantly, this competition was stimulated by plans for the second railway construction on the continent. The Kwantung Army and the SMR grew increasingly impatient to complete the northern railway line despite its high cost, low profit potential, and persistent Chinese and Korean resistance and sabotage. Two major segments of the northern railway line project were completed in 1925 and 1928, bringing the vision of a direct link between ura Nihon and the resource-rich continent closer to fulfillment. Such a direct link fired up imaginations and arguments for developing ura Nihon via connection to Manchuria and Korea. In 1928, the North Japan Steamship Company lobbied successfully for public funds to open a direct maritime route between Tsuruga in ura Nihon and Chongjin in Korea. This was supported by consular officials in Chongjin, who emphasized the importance of the direct route for the development of both ura Nihon and the Korean-Chinese borderland region of Manchuria.

Ura Nihon, “Domestic Lake,” and Imperial Autarky in Northeast Asia, 1931-1945

The Kwantung Army’s desire to quickly complete the northern railway line contributed to its radical decision to stage the Manchurian Incident on Sep. 18, 1931. For Ishiwara Kanji, the mastermind behind the Incident, the railway line was indispensable not just for defense against Soviet attack but also for a regional autarkic economy in which the Sea of Japan rim—stretching from ura Nihon to Korea and Manchuria—would be brought into a comprehensive design of defense, development, and colonization. Occupation of the whole of Manchuria expedited the planning. Army, navy, SMR, and government ministries worked together to complete the construction of the railway in September 1933 (Yoshii 2000, 244-256). Harbor construction started at Rajin which was set to replace Chongjin as the coastal terminal of the second artery line.

The Manchurian Incident, accompanied by the completion of the 10-kilometer Shimizu Tunnel on Honshu (which shortened travel time by 4 hours from Tokyo to Niigata), transformed the ura Nihon ideology into one that sought to turn the Sea of Japan into a Japanese lake. This spatial ideology can be traced back to the Russo-Japanese war and the Siberian Intervention when opinion leaders and military figures viewed the Sea of Japan as the territorial waters of Japan (Saaler 1998, 277). Its rearticulation in the 1930s was marked by two slogans: “the shortest route between Japan and Manchuria” (日満最短ルート) and “transforming the Sea of Japan into a domestic lake” (日本海の湖水化). The government-funded Association for Japan-Manchuria Businesses (日満実業協会) spearheaded promotion of the shortest route between the two “capitals” of Tokyo and Shinkyō (“new capital,” or Changchun in Manchuria), transforming the Backside into Japan’s new Frontside connecting the metropole with the continent. Local interest groups in Niigata Prefecture were particularly quick to grasp the opportunity by campaigning to develop the city of Niigata to become “the Front Gate of ura Nihon” (裏日本の玄関口) and campaigning for public funds to open trade routes to ports in northern Korea. This flip from the Backside of the nation to the Frontside of the empire points to a sharp change of spatial orientation from the Pacific to the continent. With withdrawal from the League of Nations in 1933 and embarking on the building of an autarkic empire, Japanese leaders decided to join Asia (the empire) and leave the West (autarky), turning their back not on the continent but on the ocean.

The slogan “transforming the Sea of Japan into a domestic lake,” coined by national newspapers in early 1932, was picked up by the North Japan Steamship Company for promoting its Tsuruga-Chongjin route. The slogan catalyzed competition for developing maritime transportation across the Sea of Japan in the 1930s. This competition gained government backing when an ambitious plan to send one million Japanese households to Manchuria was incorporated into the industrial, commercial, trade, and military defense planning of the Northeast Asian region as part of the Japan-centered imperial zone. In 1938, the Japanese government launched a comprehensive development plan for Manchuria, ura Nihon, and three harbors in northern Korea, leading to the establishment of The General Assembly of Economic Alliance of the Sea of Japan Region (日本海経済連盟総会). One month later, the publicly funded Sea of Japan Steamship Company was established. The Backside of Japan was now formally incorporated into Japan’s empire building and seemed on its way to becoming the Frontside of the empire.

The empire itself, however, was engaged in full-scale war in China by 1937 and the developmental logic of the early 1930s quickly gave way to the need for total mobilization. While Japanese businesses monopolized the Sea of Japan, literally changing the sea into a domestic lake, the shortest route between the metropole and the continent was unable to realize the vision of the regional autarky economic bloc. By 1941, the danger of hitting mines laid by the Soviet navy had rendered the “domestic lake” dangerous; maritime transportation was never able to expand as envisioned before the collapse of the empire in August 1945.

Rebirth of Ura Nihon, 1945-

The grand plan of imperial autarky evaporated with Japan’s surrender in August 1945. With all significant Japanese cities except Kyoto reduced to rubble by U.S. bombing and the country facing starvation and foreign occupation, any distinction between the Backside and the Frontside effectively collapsed. Confrontations between the Soviet Union and the U.S. reshaped geopolitical relationships in Northeast Asia leading to the reimagining of Japan as a homogeneous island nation. Within the framework of American dominance of the world economy and U.S. naval dominance of the Pacific, another spatial turn was enacted: Japan again was urged to look outward toward the Pacific Ocean and beyond to expand its role in a free and prosperous world while struggling to come to terms with the recent legacies of empire in the Northeast Asian continent which had now largely become communist (Friedman and Selden 1971).

Successful postwar national economic development of Japan went hand in hand with the rebirth of economic and cultural inequalities between the Pacific side and Sea of Japan side in the evolving Cold War geopolitical context. As Cold War tensions intensified, the U.S. fostered Japan’s economic growth, first through emergency procurement during the Korean War and then by opening its domestic market to Japanese products and setting the dollar-yen exchange rate in Japan’s favor. Japan’s fast-growing export-oriented economy contributed to the revival of the Pacific coast which had since prewar years been the heartland of modern Japan, i.e., the “Frontside of Japan” (omote Nihon). Industry, manufacturing, and ocean shipping reconcentrated along the Pacific coast, which came to be known since the 1960s as the Pacific Belt Zone. The postwar export-oriented economy directed the country to focus on the Pacific Ocean while increasingly turning away from the Asian continent despite efforts by Japanese business groups to return to China and left-leaning progressives seeking to build solidarity with continental socialist countries.

The formation of the Pacific Belt Zone was accompanied by a growing gap between the Pacific side and the Sea of Japan side with the latter serving as a purveyor of labor and primary materials to the former. The negative image of the new ura Nihon, in association with the continent, was reinforced by the state-facilitated project of “repatriation” (帰還) of Korean residents to North Korea. Starting in 1959 and continuing for a quarter century until 1984, the journey of nearly 100,000 Koreans (and some Japanese), all departing from the harbor of Niigata, to North Korea was a story of conspiracy, hope, and tragedy (Morris-Suzuki 2007). The Korean crossing of the Sea of Japan, coupled with incidents of abduction of Japanese to North Korea in the 1970s and 1980s, only foregrounded the distance and difference between the continent and Japan, between a bleak, oppressive communist state and a free, prosperous democracy.

Postwar re-formation of ura Nihon gave rebirth to a critical ideological position that counterposes itself to the new omote Nihon. Marking the counter position of ura Nihon was its identification with the Sea of Japan rim (kan Nihonkai) region and connections with the continent even though the use of the term ura Nihon itself was terminated in the 1960s for being discriminatory. From this counter position, people in ura Nihon waged criticisms of the Pacific-centered economic development model of the postwar period. In 1970, the regional newspaper Niigata Shimbun published a special issue Tomorrow’s Sea of Japan. Two years later, the local branch of the national newspaper Mainichi Shimbun issued another special issue titled The Era of the Sea of Japan – Its Fetal Movement and In Search of the Future. Then in 1974, a research group from seven universities in the Sea of Japan coastal region published Conception of the Sea of Japan Rim Region and Regional Development. These publications criticized postwar Japan’s development as overly oriented toward the U.S. and issued calls for a reorientation toward the continent. Eerily reminiscent of prewar slogans, they claimed that “Siberia is waiting for our collaboration. The Chinese continent is impregnated with unlimited possibilities. The time has come for trading with the shore on the other side of the Sea of Japan. The Sea of Japan coast is none other than the front gate of Japan” (cited in Furumaya 1997, 190-191). While the language resembled prewar discourse, needless to say, the call carried no imperialist inspirations although it did not seem to look at Japan and the continent on completely equal terms.

It is not until after the end of the Cold War, however, that the conception of “the Sea of Japan rim” (kan Nihonkai) was translated into concrete proposals and initiatives to construct a transnational cooperative framework. In October 1993, the Kan Nihonkai Keizai Kenkyūjo, or Economic Research Institute for Northeast Asia (ERINA) in English, was established in Niigata with funds from eleven prefectures and eight businesses in the region for the purpose of promoting economic exchanges and constructing an economic zone encompassing Northeast Asia. ERINA envisioned a developmental model of complementarity and collaboration by using Japanese and South Korean technology and capital, Chinese labor, and Russian natural resources. This model, however, soon fell behind the times as China’s economy grew rapidly during the period and by 2011 had superseded Japan to become the world’s second largest economy. The Niigata prefectural government, which currently provides 80% of funding to ERINA, decided in February 2021 to significantly reduce the funding as it sees ERINA’s role dwindling over time.

An equally important reason for ERINA’s failure is that from the very beginning it suffered from lack of international support, due significantly to Japan’s failure in coming to terms with its imperialist past. This debilitating shortage of support manifests in South Korea’s insistence on calling the waters “East Sea” rather than “the Sea of Japan.” The English name of the organization, Economic Research Institute for Northeast Asia (ERINA), avoided the use of “the Sea of Japan” apparently to accommodate South Korea’s protest. The controversy surrounding the naming of this particular body of water, which was supposed to connect rather than separate, epitomizes the obstacles that hindered and eventually crippled ERINA’s program of transnational collaboration and joint development.

Another initiative, the Kan Nihonkai Gakkai, or “Association for Sea of Japan Rim Studies,” was established in 1994 to conduct research on the region for promoting mutual understanding and exchange. However, here too, Korean scholars demanded the association not use the term “Sea of Japan.” While acknowledging the naming to be a critical issue in need of discussion and reaffirming its commitment to promoting a shared historical awareness among its member countries, it took the association more than ten years to change its name to The Association for Northeast Asian Regional Studies in 2008. The current website shows all executive members are from within Japan, compromising its call for internationality. The website itself appeared to have not been updated for more than a year and with 157 subscribing members (in 2017), the association does not seem to be able to pursue a vigorous research agenda.

It seems then that into the twenty-first century, with the term ura Nihon long gone and the Sea of Japan rim concept failing to articulate a sensible program of regional development, the ura Nihon-vs.-omote Nihon distinction, formed over a century ago, is no longer capable of offering alternative ways in which to imagine a global—or even regional—position for Japan. In 2017, Japan under the Abe administration announced a new foreign policy initiative called the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy”. With an emphasis on the values of democracy, rule of law, and market economy, as well as collaborative relations with India, the US and Australia, this “Indo-Pacific” initiative suggests a distancing of Japan from continental Northeast Asia, in particular China and North Korea. While the Niigata-based ERINA reaffirmed its goal of building an integrated Northeast Asian economic zone in its fourth medium-term plan (2019-2023), it is in no position to challenge the “Indo-Pacific” initiative arising from the central government, located in Pacific-oriented omote Nihon. The “Indo-Pacific” initiative, however, is not sufficient as it defines the relationship between Japan and the continent only in oppositional terms and does not seek to build a constructive relationship with its Northeast Asian neighbors. With China being the largest trade partner of Japan, multiple and complex approaches are required to look at China and the Asian continent not as a threat but an opportunity for peaceful coexistence and joint development. In this regard, one cannot but hope that the historical legacy of ura Nihon may still be useful in offering alternative insights, if not a concrete development plan, for imagining new possibilities for present-day Northeast Asia.

References

Abe, Tsunehisa. Ura Nihon ha ikani tsukuraretaka. Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Hyōronsha, 1997.

Friedman, Edward and Mark Selden, eds. America’s Asia: Dissenting essays on Asian-American relations. New York: Pantheon Books, 1971.

Fukuzawa, Yukichi. kuni-zukushi. Tokyo: Keio Gijuku Zōhan, 1869.

Furumaya, Tadao. Ura Nihon: kindai Nihon wo toinaosu. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1998.

Harada, Toyokichi. “Nihon chishitsu kōzō ron,” Chishitsu yōhō no.2 (1888), 309-355.

Inoue, Yuichi. Testudō geeji ga kaeta gendaishi. Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 1990.

Matsunami Niichirō. “Nihonkai ni taisuru hōjin no katsudō,” Tōhoku hyōron no.8 (March 15, 1906), 12-15.

Matsuo, Kosaburō. Nihonkai chūshin ron: kotōteki jikaku. Tokyo: Kaikoku Kōronsha, 1922.

Matsusaka, Yoshihisa. The Making of Japanese Manchuria, 1904-1932. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2001.

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007.

Oikawa, Yoshinobu. Nihon tetsudō shi: batsumatsu Meiji hen. Tokyo: Chūō Kōron Shinsha, 2014.

Pumpelly, Raphael. Geological researches in China, Mongolia and Japan during the years 1862 to 1865. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1866.

Saaler, Sven. “Nihon no tairiku shinshutsu to Shiberia shuppei: teikoku shugi kakucho no ‘kanestsu shihai soko’ wo megutte,” Kanazawa Daigaku Keizai gakubu ronshū 19, no.1 (Dec. 1998), 259-285.

Tsukakoshi, Yoshitarō. Chiri to jinji. Tokyo: Minyūsha, 1901.

Yoshii, Kenichi. Kan Nihonkai chiiki shakai no henyō – “Manmō Kantō” to Ura Nihon –. Tokyo: Aoki Shoten, 2000.