Abstract: Active from the 1960s onward, Tsujimura Kazuko (1941-2004) was an avant-garde dancer who aimed for a “dance without body, without dancing.” This paper examines how Tsujimura sought, unconsciously or consciously, to reveal how the body was harnessed for—and constructed from—production in the increasingly capitalist world of high-economic growth Japan. As we shall see, through her limited, but often tense, movement in dance, in her use of costumes in fragmented installation pieces, and in her social alliances, she sought to undo the notion that the body was an expression of free agency.

Keywords: dance, Butoh, gender, labor, conceptual art, objecthood, exports, commodity culture, mass culture, women.

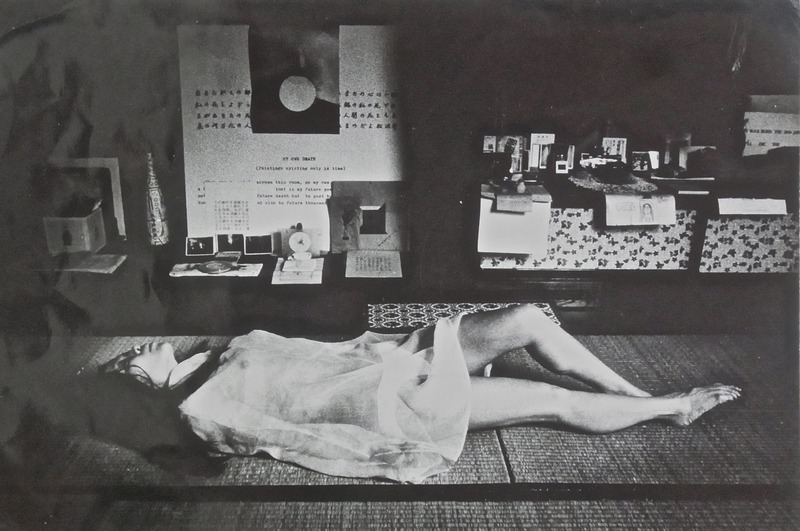

In this c. 1972 photograph taken at conceptual artist Matsuzawa Yutaka’s home in Shimosuwa, Japan, we see Tsujimura Kazuko (1941-2004) laying still, yet not relaxed.1 We note her deftly pointed toe, held tight and parallel with the tatami below her. While her hands are invisible and her face is angled away from the camera, we can clearly see her legs, the faint outline of her torso, and her protruding nipples. Her bent left leg suggests the potentiality of motion, her readied muscles outlined through the shades of the black and white photograph. Her body is held between a relaxing state of sleep, meditation, or death, and a tense state of arousal, muscular flex, and threat.

Tsujimura Kazuko, who lived from 1941-2004, was a dancer and artist (like many of her peers active in the avant-garde scene, she did not distinguish between the two genres), who claimed she performed a ‘dance without body, without dancing’. Yet rather than a full negation of the body that this opaque description of her work might bring to mind, Tsujimura’s artworks, photographs, and performances used silhouettes, masks, and translucent materials that were at once animate and inanimate, fragmented and whole. This essay examines how Tsujimura’s oeuvre fractures the human/object binary to instead show us the woman-as-object constructed through masks, fabrics, and labor.

While many artists, dancers, and musicians in the United States as well as in Japan were thought to be using art as an outlet of personal expression, other artists, such as Tsujimura, seemed to understand that the notion of pure individuality was a bygone ideal rather than a reality. For Tsujimura, I argue, the self was defined through objectification from the structures of gender, race, and the intense capitalist development of 1960s Japan and the rise of the global marketplace. The feminization of Japan that began with the so-called “opening” of the country under Commodore Perry, continued with the American Occupation of Japan and the “economic miracle” of the 1960s. Exports from Japan to the United States heightened the sense of Japan’s “ornamentalism:” as a country that was feminine, exotic, and available. According to Anne Anlin Cheng, “Ornamentalism” is “…a conceptual paradigm that can accommodate the deeper, stranger, more intricate, and more ineffable (con)fusion between thingness and personness instantiated by Asiatic femininity and its unpredictable object life.”2 Ornamentalism thus reveals the ways that objecthood is not held in opposition to personhood, so much as it is deeply entangled with what personhood is understood to be.

Cheng’s model, building on Edward Said’s concept of orientalism, is assumed to refer to the strains, effects, and constructs of a Western viewer onto the East Asian woman. Yet, by the late 1960s and 1970s in Japan, it is easy to see how desire for the “decorative grammar” of the ornamental woman had been internalized and accentuated through American imperialism, trade, and uneven globalization. Starting immediately at the end of the war, Takuya Kida points out that “…craft products were chosen as a form of payment in kind for food imported from the USA.”3 These crafts products included fabrics, lacquer objects, bamboo, and dolls. According to a survey of American Officers, “… the designs should be simple and should feature purely Japanese forms and patterns, and the most favored decorative motifs were those based on birds and flowers.”4 The demand, and even economic reliance on craft exports created an “acute awareness of American attention; this led to a re-examination of ‘tradition,’ and the recreation of this from a vague notion of ‘Japaneseness.’”5 In other words, the correlation between Japan and the decorative was a concept imbedded in trade: a concept demanded by the United States market, and supplied by Japanese craftspeople and laborers.

In the 1960s and 1970s, at a time in Japan when women’s bodies were either harnessed for the factory workforce or understood to be part of a decorative backdrop, Tsujimura often negated the body in her work, revealing instead the dangers of a subject that can be disassembled and replaced. Her work aligns with the growth of the women’s liberation movement, which had critiqued the male-dominated left-wing youth movement.6 This paper examines how Tsujimura sought, unconsciously or consciously, to reveal how the body was harnessed for—and constructed from—production in the increasingly capitalist world of high-economic growth Japan. Like Cheng, Tsujimura seems to acknowledge and expose how her Asian, gendered body straddles the space between co-optation and agency. As we shall see, through her limited, but often tense, movement in dance, in her use of costumes in fragmented installation pieces, and in her social alliances, she sought to undo the notion that the body was an expression of free agency. The young artist’s dance revealed the blurry line between personhood and objecthood, exposing how the gendered figure was co-opted by the mechanisms of state capital. Tsujimura fractures the human/object binary, and instead shows the “ornamental” woman as constructed through masks, fabrics, and machines.

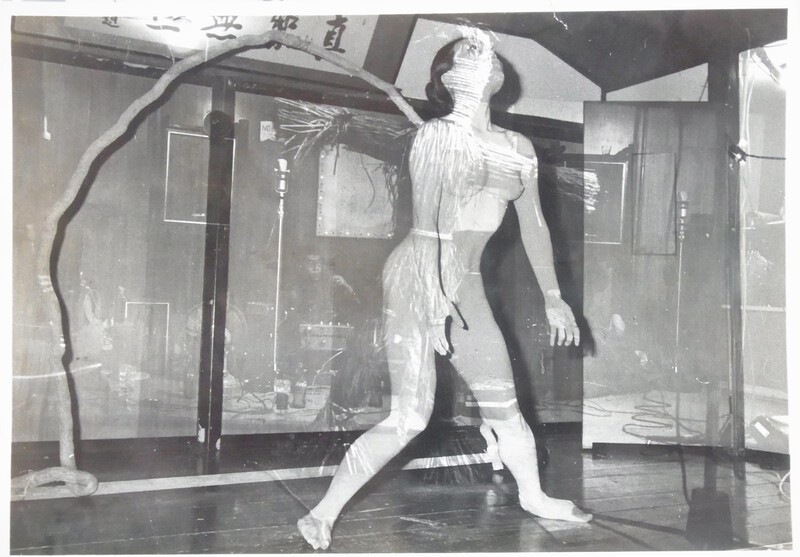

Although there are a limited number of photographs of Tsujimura’s performances and artworks, those that remain demonstrate her heightened ambivalence toward the concept of the naturally expressive body. For example, Tsujimura’s contribution to the 1972 event “Catastrophe Art,” (figure 2), World Uprising, seems to mock the idea of unique personhood and suggests women are little more than disposable, repetitious, amusements. In the installation piece, her body is obscured by a white dress hanging by string, reminiscent of puppetry. This effect is magnified by the cut out of the hand shaped as though holding a string in the background. Other silhouettes of hands further complicate the image, making it hard to discern which hand belongs to which body. Similarly, the silhouette of the head alongside her own suggests the individual body is not so different from a doll: from the view of the labor market, we are constructed and replaceable. Notably, the edges of her arms are visible, as if to suggest that this process of replacement is imperfect. These cut outs prefigured Kara Walker’s use of the silhouette to problematize the ways representations have been used to claim ownership over the female body.

Tsujimura’s feet are not visible in the work. Feet and legs are arguably central to any dancer’s identity: they stamp, they turn, they stand en pointe. Tsujimura’s erasure of the feet could be read as a symbolic negation of this identity in dance, an insistence that dance can be other than movement, other than expression. In the piece, the body is invisible, the dress hanging loosely in its place. Only her playfully neutral face is visible at top. When the piece was displayed in Milano, Tsujimura was not present, and the dress was exhibited with instructions for viewers to “wear” it, thereby denying the artwork as a unique, expressive outlet and suggesting instead the uneasy transferability of identity.

Tsujimura’s work here is comparable to Gutai Art Association member Tanaka Atsuko’s earlier rendition of the troubled female body.7 Tanaka’s 1956 work, Electric Dress, reveals a lack of fixity in the subject, a sense of uncertainty about the strength and physical presence of self.8 Subjective identification, for her, was circuitous, experienced through connection, disconnection, and repetition. Given that artists like Tanaka and Tsujimura made artwork that denied the expressive primacy of the body, we might ask: What social and historical factors might have motivated this tendency?

Women and the Object of Labor

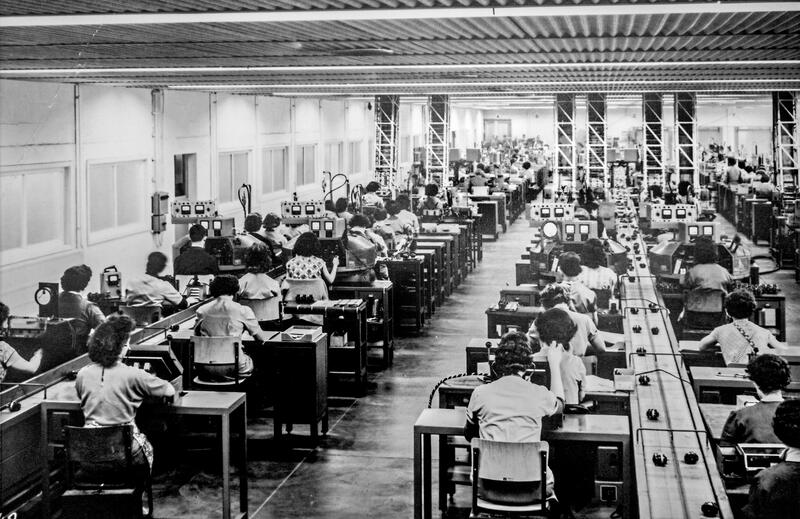

In the late 1950s and 1960s, there was a push for economic growth in Japan, which led to startling changes in people’s everyday lives. According to Eiko Maruko Siniawer, “[t]he groundswell of consumerism was officially characterized as a “consumption revolution” in 1960 by the Economic Planning Agency, which also detailed the “lifestyle revolution” it entailed.”9 The high-growth era also saw chronic labor shortages and the tightest labor market in Japan’s postwar history.”10 Prime Minister Ikeda introduced the “income-doubling” program, which he promoted from 1960-1964. It might be noted that the program, which sought to increase the gross national product within a decade, as well as raise household income, specifically sought to harness women as a source of labor power.11 The policy “referred to women’s employment and its significance for increasing income and recommended that firms investigate childcare leave and other policies that would help utilize women’s talents and abilities. These recommendations were framed in terms of encouraging women’s employment for the sake of growth, not for women’s equality. The plan also emphasized the importance of children as the future labor force and the need to ensure their well-being” for that purpose.12 As a result, “[t]he change in women’s labor force participation was dramatic: between 1962 and 1975, the total number of women employees grew by 44 per cent (from about 8 million to over 11 million workers).”13 In Assembled in Japan, Simon Partner explains how the darker side of the industry leaned heavily on women’s labor: “Electrical goods companies competed directly with textile factories for young female labor.14 Underneath the apparent revolution in technology development and industrial structure lay a profound continuity based on the abundance of extremely cheap, relatively docile female labor.” Both Tanaka and Tsujimura raise the relation among labor, the body, and textiles in their work.

These artists seem to address how, during the 15-year-war, and again in Japan’s postwar push for economic recovery, the state treated citizens’ bodies like machines or toys composed of parts, parts that could be disassembled and replaced: utilitarian but easily discarded. Tsujimura and Tanaka used their art to draw attention to the fact that the female body, in particular, was often seen as little more than a doll, a manufactured ornament for display of wealth and capital accumulation. What is more, these artworks draw attention to the fact that female labor lay at the heart of Japan’s so-called economic miracle (see figure 3).

Although Tsujimura may not have been aware of the rising number of women in the workforce, there is no doubt that she would have experienced the increasingly intense, and often contrasting, demands on women’s bodies as caregivers, housekeepers, and workers. Anxieties surrounding women’s role in society had profound effects.

Mass Ornament

In the untitled photograph from c.1973 (see figure 2), the smooth continuity between Tsujimura’s whitened face and the blank whiteness of the silhouette deliberately creates a sense of ambivalence about “the real” as it pertains to corporeality. Was the silhouette created from a person, and then the person constructed themselves after the silhouette? Or are they one and the same? Does the white dress shield the body, symbolize, or actualize the body? Light contours vaguely visible behind the dress suggest, but do not confirm, bodily presence. As a whole, the dress and its wearer hover between object and person. Tsujimura reveals how womanness and the ornamentalist presence are already intertwined.

In “The Mass Ornament,” Siegfried Kracauer has described the ways that the Tiller Girls (Figure 4), a precision dance chorus popular at the turn of the century and revived again in the 1950s, were “distraction factories” created to serve the masses of salary workers who lacked spirituality and were divorced from custom and tradition. According to Kracauer, “…the hands in the factory correspond to the legs of the Tiller Girls.” Tsujimura, too, seems to recognize dance as Mass Ornament, a staged rationalization of the body that feeds into the machines of capital, and grew from the alluring images of unified, military bodies, such as in Imperial Japan. The dance troupe produced women as “…ornaments …composed of thousands of bodies, sexless bodies in bathing suits.” For Kracauer, the Tiller girls are unified and objectified to the point that eroticism is removed, and the bodies can only be understood rationally, as a series of “…arms, thighs, and other segments.”

While the Tiller Girls were originally a British phenomenon, and then popularized again in the United States in the 1950s, synchronized dancing also took Japan by storm in the postwar. Initially cabaret girls were paid to entertain the large number of US troops in Japan and were soon frequently depicted in films such as those by Suzuki Seijun, girls doing synchronized dancing in Kinoshita Keisuke’s Onna (The Lady, 1948), or the synchronized men and women dancing in Masumura Yasuzo’s critique of corporate culture, Kyojin to gangu (Giants and Toys) (1958). Enthusiasm for ballet schools also grew, and it became nearly synonymous with Western Dance. Thomas Havens writes: “In the mid-1950s ballet became a disarmingly gentle weapon of cultural diplomacy in the cold war, bringing the Bolshoi, Leningrad, and New York City ballets for tours that stimulated Japanese dancers to form fresh companies of their own.”15 Havens points out that the middle classes began to spend exorbitant amounts on private lessons and performances on postwar dance, largely, he contends, to entertain themselves and to contribute to their child’s gentility. “Being a good wife and wise mother, the prewar formula, was redefined to mean mastering the skills of Beauty and acquiring an air of cultivated refinement.”16 All of this social civilizing turned on disciplining the body.

This kind of dedication of the physical and emotional self for mass distraction is what many artists and dancers, including Tsujimura, sought to expose or reject. In this way, Tsujimura might be aligned with her contemporary, American Yvonne Rainer, and her insistence on an “anti-spectacular dance.” Carrie Lambert (Beatty) describes Rainer’s Trio A as a “determined clockwork” that “continues to counter the photographic structure that supports dance-as-display. Trio A has a prime directive: constant motion. Rainer’s formal innovation is to suppress all starts and stops within the dance; to level out the modulation and emphases of traditional phrasing.”17 Tsujimura, on the other hand, performs an anti-spectacular dance that hinges on the frozen moments, rather than deny them.

As William Marotti has suggested, “Artists in Japan discovered hidden forms of domination in the everyday world and imagined ways in which their own practices might reveal, or even transform, such systems at their point of articulation in people’s daily existence.”18 In the postwar period, as women’s labor was sourced for the so-called economic miracle, artists like Tsujimura rejected the forms of dance and entertainment growing increasingly popular that enervated the body of eroticism, spiritualism, in favor of rationality and economic growth, and experimented with a form of conceptual dance that asked viewers to consider how dance lulls the spectator into the rhythms of mass consumerism.19

The foreboding side of synchronized female bodies was also raised by Moriyama Daido, in his photograph, Shibuya, from 1966.20 In a still shot, the majorettes’ legs jut out like weapons, darkly paralleling the electrical wiring above. Their white hats and boots and the verticality of their bodies echoes the advertising in the background, furthering the sense that the women are little more than ornaments of capital. Moriyama, like Tsujimura and Tanaka, shows us the instability of the female body, its replaceability, its ability to transform, or to disappear into mass ornament. It should be noted too, that this goes against the grain of most art historical scholarship, which repeatedly argues that art in postwar Japan was about a newfound expression of individualism. Neither Matsuzawa nor Tsujimura fit into this problematic framework, which overlooks the ways individualism and modernism were well-developed in Japan before 1945. Tsujimura is more cynical than those artists promoting individualism. She destabilizes the accepted notion that the body is a direct expression of the self and forewarns of the body’s disaggregation by capitalism into parts that, like Kracauer’s Tiller Girls, can no longer be “reassembled into human beings.”21

For Tsujimura and other artists of the time, the question of the body remained central: how could the body make art without being co-opted by the state? Without becoming a machine of capital or a mass ornament? How could a woman evade the role of “good wife, wise mother,’ a concept that the government had adopted during the war and continued to promote in the postwar period, without being seen as an unscrupulous woman?22

Before exploring further how Tsujimura achieved this, let us turn to a brief background of her life. During the war years, jazz was outlawed, and Tsujimura’s family moved to Dairen, where her father was trying to pursue a career as a jazz musician. Tsujimura was born in 1941 in Dairen, Manchuria. Her parents, who met at a dance hall, encouraged dance but could not afford to pay for lessons.23 In 1947, Tsujimura’s family returned to Japan, and moved to the Shinjuku district, living in poverty in a single room of her uncle’s house.24 Kazuko’s brother Makoto recalls that even at this early age, her sister was interested in dance, but her parents were too poor to afford lessons, and Makoto recalls they could not afford schoolbooks or lunch. Their father left for long periods, and soon their mother took up work “hostessing”mizushobai (sexualized entertainment) and was no longer at home. Throughout elementary and middle school Kazuko and Makoto stayed separately with different relatives, only living with their mother again in Aomori after Kazuko graduated from middle school. Then, Kazuko’s mother became ill and Kazuko was forced to drop out of her evening high school classes, working full time at the hip café, Ruskin, in Shinmachi, Aomori.25 Since many avant-garde artists and intellectuals gathered there, Tsujimura soon found herself involved with local art circles, meeting critics and writers such as Terayama Shuji. She began modeling for photographers and eventually joined the theatre troupe, Yuki no Kai.26 She later moved to Tokyo, where she collaborated with writers, dancers, and artists, first joining a group called Jaku no Kai, led by the artist Sasaki Kosei. In 1964, she worked predominantly on conceptual dance, learning from and then collaborating with Kuni Chiya for ten years.27

Kuni Chiya was a contemporary of Hijikata Tatsumi and other Butoh dancers (although it should be noted Tsujimura was not affiliated with the Butoh movement).28 Butoh was the prevailing experimental dance of the 1960s, that, according to Butoh scholar Bruce Baird, sought to negate utility in dance, often focusing on maintaining bizarre postures, gender bending, and shocking their audiences. Baird argues that Butoh, like other avant-garde movements, sought to veer away from production and consumption, at a time when Japan was urging all citizens to make sacrifices to contribute to economic growth.29

Like Tsujimura, then, Butoh offered a critique of the everyday systems of production and consumption. Yet there were also strong differences between the two. In Hijikata’s dance, demanding twists of the torso were often required to demonstrate the “Revolt of the Flesh” from utility, the ability of the body to overcome modern convention. Dance, for Hijikata, could still suggest personal expression. His dance declared the primacy of the body, while Tsujimura exposed the body as an object, unavoidably shaped by the forces of capital.

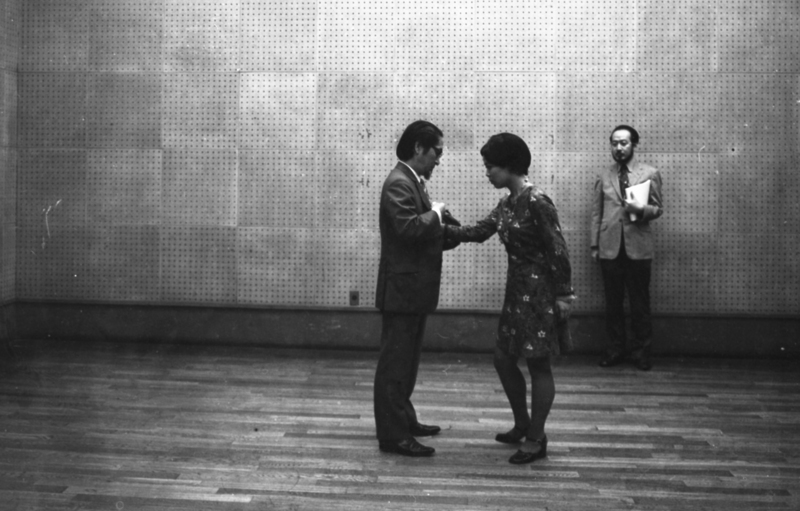

Tsujimura’s conceptual notions of dance led her to collaborate with Matsuzawa on several occasions.30 For example, in figure 1, Tsujimura is situated within Matsuzawa’s home, a detail of one of their collaborative works, My Own Death (1970), behind her.31 Tsujimura first met Matsuzawa in 1964 when she participated in Independent in the Wilderness. This was around the time that Matsuzawa, in June of 1964, described having a revelation, wherein a voice told him to “eradicate all objects,” a story which is now taken as the beginning of his kannen or conceptualist ideas (although others link it to his work in the 1950s).32 Artists such as Ikeda Tatsuo (who is now widely categorized as a reportage artist), and the surrealist Takiguchi Shuzo sent mail art to that exhibition, whereas Tsujimura sent simply her “idea.” How the idea was sent and received, and what the idea was, remain unknown to us.

In 1969, she presented Matsuzawa’s conceptual work ‘Nil’ at the Rokkasen dance recital at Honmoku-tei (a venue that was normally used for traditional storytelling, or kodan yose) in Tokyo.33 Matsuzawa’s ‘Nil’ message was:

‘Kazuko Tsujimura aims at the dematerialization of dance.

It is the final form of human dance.

In the future, she will dance a dance of non-dance.

Tonight, please do NOT see Tsujimura’s ‘Nil’ body and its space and time.

Rather, try to see her concept, her spiritual body after death and disappearance of all things

– that is the truth of ‘Nil’.

Gyatei.

Imaginary Space Research Center’34

In this performance, Tsujimura lay naked, and then later stood, on a dark stage with her ears, nose, and vagina, painted with fluorescent pigment. She refused to make any ‘dance’ movement except minimal lying and standing. Photographs show her legs spread apart, in an unnatural pose as though they are not supporting her weight. Her arms hang in a discomfiting position, like that of a doll, and her head and gaze face upwards, disengaged from the crowd (figure 5). She seems to work to both expose and deny the power and eroticism that her young, nude body presents. Her insistent inanimate “dance” gives the lie to the notion of free agency, revealing the body to be decorative and constrained.

The piece was later displayed as a photographic work (see figure 5) in the 1977 Sao Paulo Biennial.35 In this version, we see her nude body overlaid with a straw effigy, which was a photographic after effect. Behind her, a tube or a branch appears to be thrust into her back, giving the impression that her body is nothing more than a puppet, hanging loose from a larger system. The effect of the straw effigy further disrupts our access to the body. Instead of the supple texture of flesh, it appears as though the surface of the photograph has been scratched out, and the distinguishing characteristics of her upturned face are made even more inaccessible to the viewer. Tsujimura’s nude body thus turns the visual pleasure of the ornamental doll upside-down: instead of passive consumption, viewers are made aware of their desire for the object. Instead of a life-like doll we are reminded of a death-like woman, underscoring the relation between the two.

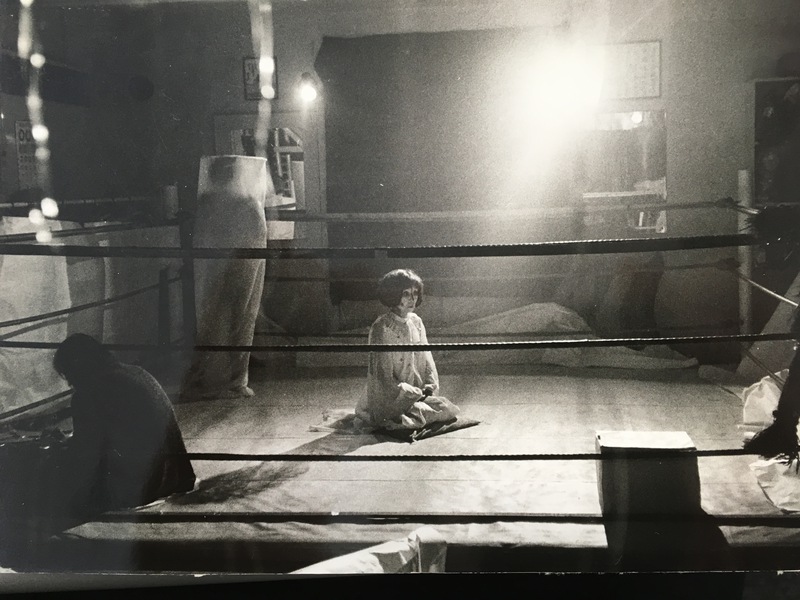

These interests in rejecting the norms of movement and self-expression in art continued as Tsujimura formed the Parnirvana Paryaya Body (or PPB group). The name originates from the Sanskrit terms Nirvana and revolution, and the dance group included Tsujimura, Sekido Rui, and Suzuki Yuko).36 On December 19th and 20th 1970 the group performed at the Nitto Boxing Gym and included Tsujimura’s mother in the performance (figure 6). In the photograph, Tsujimura Masako, who was supportive of her daughter’s performances, is seated in the center. (This was the only occasion where she was an active performer with her daughter). The performance again disavows bodily movement, and instead features a woman sitting still in the ring. Other dancers, including Tsujimura Kazuko, were dressed in transparent white, their faces painted in a manner that recalls the yokai or spirits of the deceased. Kazuko was positioned along the side of the ring, wrapped in cylinder-shaped, semi-transparent material. Tsujimura’s mother sits seiza (in the traditional Japanese position with her knees tucked away) on top of a cushion, her gaze, wide-eyed yet without any focus. The stage lights make clear that this is a performance (if the 800-yen entrance fee did not), yet the protagonist remains still and disengaged. The locale is also important: the group chose a boxing ring, a site that was typically reserved for male competitive violence, to complete an all-female negation of movement.

Death was likely on the minds of the artists gathered at the Nitto gym. The previous month, Nobel-nominated author Mishima Yukio had stunned the nation with his failed coup d’état and dramatic seppuku ritual suicide on November 25th, 1970. Mishima, a right-wing nationalist who opposed Japan’s turn to democracy, had formed an unarmed militia called the Tatenokai (Shield Society) that venerated the Emperor. The group of five men stormed a military base in Ichiyaga, Tokyo, and took a commandant hostage, hoping to inspire an uprising to overthrow the 1947 Constitution and restore the political primacy of the Emperor. Mishima himself then stepped onto the balcony, reading their manifesto aloud, and ending with the phrase, Tenno-heika Banzai! “Long live the Emperor!” The Mishima Incident (Mishima jiken), as it is known in Japan, was performative and bloody. After Mishima had read his manifesto and declarations, he stepped inside and performed ritual seppuku. His militia member, Morita Masakatsu, was then supposed to complete the ritual by acting as his kaishakunin and decapitating him, but after three failed attempts could not complete the decapitation. Morita then stabbed himself. Finally, another member, Koga Hiroyasu, decapitated both Mishima and Morita. The incident was a mesmerizing tale of disaster and was widely covered in the press.

Given that Tsujimura’s performance at the Nitto gym in Tokyo was held just weeks after this violent spectacle occurred in the same city, it seems likely that the PPB group was responding to the overwrought, violent, and nationalist spectacle with a nuanced and ironic non-performance.37 Sitting still and wordless in an arena intended for violence (and even death), her negation of action and her quiet insistence that the body was not a vehicle of expression, nor something to be sacrificed in the name of the Emperor, resonated with those who were reminded of the lingering presence of the imperial desire expressed by Mishima’s actions.38

That same year, Tsujimura participated in a performance at the important exhibition, Tokyo Biennale 1970: Between Man and Matter, held in the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum and organized by Mainichi Shinbun (part of a long-running tradition of newspaper companies supporting art).39 The exhibition included forty artists selected by Nakahara Yusuke, a leading critic of contemporary art and the exhibition commissioner, and the event had the support of most avant-garde artists, unlike the corporate spectacle of Expo ‘70. There was no award given, and no sense of representation by nation, hence in this respect the Tokyo Biennale was a rather cutting-edge, transnational event. It included mostly young artists from 25 cities in Japan, and it also showcased influential European and American artists like Hans Haacke, Daniel Buren, Christo, Luciano Fabro, On Kawara (who was then resident in NYC), Richard Serra, Bruce Nauman, and Sol Le Witt. Reiko Tomii has convincingly argued that this biennale set the precedent for Japan’s emergence on the global art stage.40 Yet, one of the major failures of the event was that no female artists were formally included, despite other female artists having participated in other important exhibitions.41 Thus, Tsujimura’s performance seems all the more significant.

Tsujimura, who was not listed in the exhibition catalogue, performed a collaborative work with Matsuzawa, entitled My Own Death (figure 7). In My Own Death, Matsuzawa and Tsujimura highlighted their mutual interest in the tensions and cycles of the body. The work consisted of one or two panels, marking the entrance(s) to an empty room, where the pair performed. The text on the panel, both in Japanese and English, asked the viewer to reflect on the artist’s death along with the trillions of previous, and future, deaths of humans to come.

Tsujimura, in her previous works, exposed the ambivalent passivity that constitutes the gendered, Asian body. Yet in My Own Death, she becomes the active force that brings about Matsuzawa’s conceptual death. With intermedia artist Yamaguchi Katsuhiro serving as a witness to the whole rite, Tsujimura touched Matsuzawa’s chest through an opening in his shirt and felt his heartbeat until she could visualize his death. Interestingly, Matsuzawa’s stated intent to have his death imagined is complicated by the interaction between Tsujimura and Matsuzawa. Instead of death, viewers must have also registered a moment electrified by a sexual charge.42 Here, Tsujimura stands with her legs shoulder-width apart, her gaze intently focused on Matsuzawa. She is in an equal, if not dominant position. Although she wears a dress bedecked with a flowery pattern and feminine high-heeled shoes, her stance denies any sense of feminine submissiveness. It is Matsuzawa who gazes passively at her while her hand touches his bare chest. In this way, Tsujimura simultaneously acts as the object of desire, and the wielder of power over Matsuzawa.

This seeming electric charge between the two of them is further heightened by the presence of Yamaguchi Katsuhiro, who plays “witness,” or perhaps voyeur. He wears a suit, like Matsuzawa, holding some papers, as though to further authenticate his serious presence. His gaze, at least in the photograph, is directly at the contact point between the two figures, and his neutral, watchful expression seems to authorize, or to make us aware, of our own gaze. One can’t help but wonder, will the hand slip lower? Does he want it to? Are they thinking about “death” or thinking about life and connection? Or is the point that the two are inexorably tied? Where and when is the slippage from animate to inanimate?

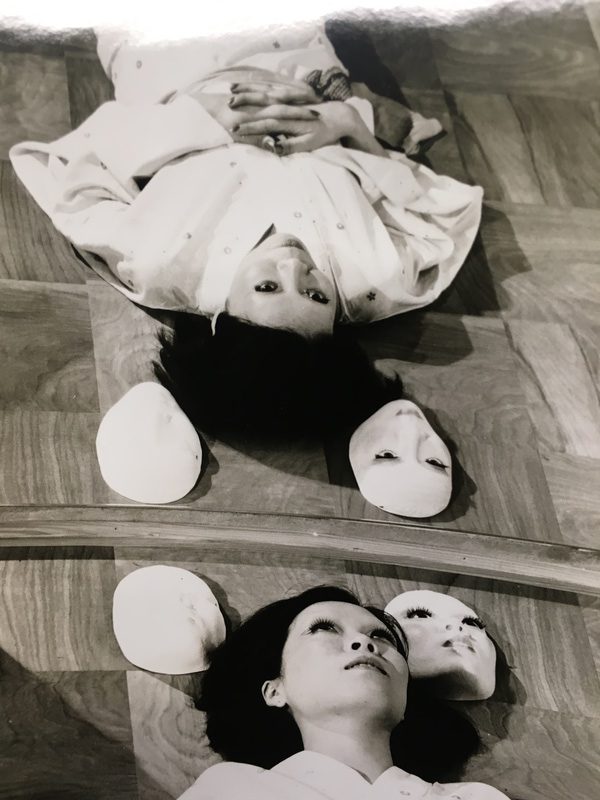

In this and other works, Tsujimura liked to play with the erasure of the corporeal body and the masking of identity. At times she did this by literally collapsing the differences between masks and faces (figure 8). In this eerie undated image, we see her lying down perpendicular to a mirror. To each side of her head, she places a mask: one unfinished mask that is shaped into a visage, but is void of specific features, and one to her left that resembles her face, complete with feminine eyelashes. Tsujimura lays still, her mouth slightly ajar, echoing the expressionless, finished mask. The transition from blank mask, to Tsujimura’s face, to the finished, feminine mask reveals that faces—something we normally deem to be unique and expressive of individuality—can also be transformed, can vanish, and can mislead. The face, normally understood to be singular and ultimately individual, is indecipherable from the ornamental mask. Tsujimura exposes the intimacy between the oriental thingness of a mask and the person who wears it. The eerie thrill we experience as we gaze at the photo challenges the viewer to question their assumptions about personhood and its relation to its supposed other: objecthood. Tsujimura fractures this human/object binary, and instead shows the “ornamental” woman as constructed through masks, fabrics, and machines.

Tsujimura’s work thus creates an interplay between the gendered living body and its masking. While Matsuzawa often sourced Shinto spiritual ideas, Tsujimura studied and referenced Noh in the late 1970s.43 Her costumes played with the visual language of Noh theatre, a classical musical theatre that has been performed since the 14th century and retains the designation of Important Cultural Property today.44 Noh is often based on traditional folktales, which involve a supernatural being who is transformed into human form as the protagonist of the story. Masks represent women, the elderly, and children, and it is this visual feature of Noh (an otherwise highly codified mode of theatre) that Tsujimura most often gravitated to, appealing to her interest in transformation and the supernatural, but more importantly, revealing the ability of the self to shape-shift, and for personhood to be intricately linked to objecthood.

To be clear, Tsujimura’s use of masks was not a matter of an artist drawing on her “traditional cultural essence,” since the mask was loaded with contemporary rhetorical significance. As Kenichi Yoshida aptly describes, the mask was a signifier of tensions between human other and thing, debated among intellectuals in the 1960s and 1970s. The Japanese critic and theorist Hanada Kiyoteru (1909-1974) wrote:

Why is it that you, in front of others, so willingly put on a mask? This is not just in front of others for it appears that even when alone, you sometimes forget to take off your mask. Is it because by wearing a mask with a defined set of expressions and clear outlines, you prevent your constantly shifting face, a sensitive face quite susceptible to external stimuli, to be exposed to others’ eyes? Or are you trying to draw people in by accentuating your facial features? Or are you just bored with your face and wish to possess another one? Either way, I have never seen your true face…45

As Hanada insists, “…a mask is not something that liberates one from a true face, but something that allows for it to come into being.”46 While other thinkers, like Watsuji, saw the mask as maintaining interior and exterior social alignment, Hanada, Yoshida points out, rejected the authenticity of a “real” underlying subject: For Hanada, “A subject takes place on the surface—the interior space beneath or behind a face is merely a set of contingencies and doubts without a profound personality waiting in reserve to express itself.”47 Tsujimura, who was a part of the social circle of artists and critics, seemed to align herself with Hanada’s view: that the authenticity of the true self was a myth.

Taking her oeuvre as a whole, it seems the young artist was invested in “…the complex dynamics between subjecthood and objecthood,” asking us to “…shake loose some of our most fundamental assumptions about what kind of person, what kind of injury, or indeed, what kind of life can count.”48 For Tsujimura, art was about the relation between objecthood and personhood, about finding a way that was outside of consumption but not claiming to be free from its structures.49

Notes

Photograph taken by Kusuno Yuji, a photographer and producer who worked with Tenji Sajiki and J.A. Seazer. Kusuno’s younger brother was a Butoh dancer.

Takuya Kida, “Japanese Crafts and Cultural Exchange with the USA in the 195OS: Soft Power and John D. Rockefeller III during the Cold War,” Journal of Design History 25, no. 4 (2012): 380.

See Christopher Gerteis, Gender Struggles: Wage-Earning Women and Male-Dominated Unions in Postwar Japan, Harvard East Asian Monographs 321 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Asia Center, 2009); Chizuko Ueno, Nashonarizumu to jendā = Engendering nationalism (Tokyo: Seidosha, 1998); Chelsea Szendi Schieder, “Human Liberation or ‘Male Romance’?: The Gendered Everyday of the Student New Left” in The Red Years, ed. Gavin Walker (New York: Verso, 2020), 143-159; Ota Motoko, “Onnatachi no zenkyōtō undo” [Women’s Zenkyoto Movement] Zenkyōtō kara ribue e [From Zenkyōtō to Lib] ed. Jugoshi nōto sengohen, (Kawazaki: Inpaukuto shuppankai, 1996).

See Namiko Kunimoto, “Tanaka Atsuko and the Circuits of Subjectivity,” in The Stakes of Exposure: Anxious Bodies in Postwar Japanese Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

Eiko Maruko Siniawer, Waste: Consuming Postwar Japan (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018), 61.

Priscilla A. Lambert, “The Political Economy of Postwar Family Policy in Japan: Economic Imperatives and Electoral Incentives,” The Journal of Japanese Studies 33, no. 1 (2007): 11.

See Hanabusa’s 1964 photographs of farming women working on transistor radio parts and resistors in Hanabusa Shinzō sakuhin ten, no. 50 of JCII Photo Salon (Tokyo: JCII Fuotosaron, 1995), 6-7.

Simon Partner, Assembled in Japan: Electrical Goods and the Making of the Japanese Consumer (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 209.

Thomas Havens, Artist and Patron in Postwar Japan: Dance, Music, Theater, and the Visual Arts, 1955-1980. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 219.

William Marotti, Money, Trains, and Guillotines: Art and Revolution in 1960s Japan (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 3.

Generally speaking, conceptualism in Japan has been largely overlooked until very recently. Recent exhibitions at Ota Fine Arts (2017) and Yale Union (2019) on Matsuzawa’s work as well as Yoshiko Shimada’s writings have begun to reverse that trend. Yoshiko Shimada, “Matsuzawa Yutaka and the Spirit of Suwa” in Conceptualism and Materiality (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 272.

Siegfried Kracauer, and Thomas Y. Levin. The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays. (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1995), 78

Derived from an idealized traditional role for women, the four-character phrase Good Wife, Wise Mother or Wise Wife, Good Mother (ryōsai kenbo) was coined by Nakamura Masanao in 1875. It represented the ideal for womanhood in the East Asian area like Japan, China, and Korea in the late 1800s and early 1900s and its effects continue to the modern day.

Her father moved to Manchuria during the war, as he was unable to find employment in Japan (as jazz was banned).

It is important to bear in mind that there really were no boundaries between the production of art, music, dance, politics, and writing at this time. All too often, scholars, in accordance with the boundaries of University departments, study one practice in isolation from others, overlooking how much these practices and people co-evolved, never insulated from one another.

Kuni Chiya was an avant-garde female dancer. Her studio, Kuni Chiya Butoh laboratory, was in Komaba, Tokyo. In the early 1960s she collaborated with Group Ongaku, Araki Nobuyoshi, Kazakura Shō and other members of the avant-garde.

See Bruce Baird, Hijikata Tatsumi and Butoh: Dancing in a Pool of Gray Grits (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 5-7. For more on Butoh, see Bruce Baird and Rosemary Candelario, The Routledge Companion to Butoh (New York: Routledge, 2019).

Conceptual art, also referred to as conceptualism, is art in which the ideas involved in the work take precedence over traditional aesthetic, technical, and material concerns.

Matsuzawa 1982, 42. Others have argued that this began in the 1950s. See Yoshiko Shimada, “Matsuzawa Yutaka and the Spirit of Suwa” in Conceptualism and Materiality (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 272.

I cannot be sure she did not direct her gaze at the crowd at other moments during the performance, but the only other photographs of this event show Tsujimura lying still on the ground, giving an impression of disengagement.

The name ‘Parinirvana Pariyaya Body’ (PPB) name uses characters that play on body and group. In 1974, Tsujimura started her own dance school, and held numerous events while working with Matsuzawa, and the PPB group. In 1975, she and Kuni had a joint recital named ‘Fall from Quiet Everyday’ with Matsuzawa, Ikeda Tatsuo, Araki Yoshinobu, and others as guest directors. Later in the 1970s, she went to India, then to Bali. She was fascinated by traditional Bali dance and introduced it to Japan in the 1980s.

Steve Ridgley has pointed out how boxing appeared frequently in the works of Terayama Shuji, a critic and writer who was also a long-time friend of Tsujimura’s. Terayama, along with much of the world, found themselves increasingly interested in boxing as Muhammed Ali’s career and reputation grew. Ridgley argues that boxing appeals for the elements of fantasy it employs: shadow boxing, knockouts in place of murders, and fights that are motivated by competition rather than a natural expression of anger. Steve Ridgley, Japanese Counterculture: The Antiestablishment Art of Terayama Shuji (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 69.

The Mishima Incident helped inspire the formation of New Right (shin uyoku) groups in Japan, such as the “Issuikai” founded by some of Mishima’s followers. Itasaka Gō and Suzuki Kunio, Yukio Mishima and 1970 (Tokyo: Rokusaisha: 2010).

Tokyo Biennale ’70: Between Man and Matter was held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum, May 10-30, the Kyoto Municipal Museum, June 6-28, and the Aichi Prefectural Art Gallery in Nagoya, July 15-26, 1970. It is also known as 10th Annual International Exhibition, Japan. For more on Expo ’70 see Review of Japanese Culture and Society 23 (2011).

“If, for better or worse, Osaka Expo was a cultural monument of postwar Japan through which the nation asserted its international standing, Tokyo Biennale was no doubt a legendary moment in postwar Japanese art, which embodied its “international contemporaneity”(kokusai dōjisei) in a tangible form. Reiko Tomii, “Toward Tokyo Biennale 1970: Shapes of the International in the Age of ‘International Contemporaneity’” Review of Japanese Culture and Society 23 (2011): 191-210.

Hannah Slater, “Unlocking the Exhibition: Tokyo Biennale ’70: Between Man and Matter,” unpublished graduate paper, 2020.

Yoshiko Shimada has recently argued that Matsuzawa was also interested in the sensual. She writes: “…—contrary to his insistence on the non-material and non-sensual—[he]also created works that were large, imposing, and imbued with sensuality.” She argues that “…this contradiction arose in part from his connection to the ancient spiritual practices of Suwa, which were deeply rooted in themes of eroticism, procreation, death, and rebirth.” Yoshiko Shimada, “Matsuzawa Yutaka and the Spirit of Suwa” in Conceptualism and Materiality (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 294.

According to documents in the Tsujimura archive now (as yet uncatalogued) held at the Keio Arts Center.

See Yoshiko Shimada, “Matsuzawa Yutaka and the Spirit of Suwa” in Conceptualism and Materiality (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 272.

Translated by Kenichi Yoshida in his forthcoming book, Avant-Garde Art. Originally published in Hanada Kiyoteru, Abangyarudo geijutsu (Tokyo: Kodansha bungei bunko, 1994), 30.

Kenichi Yoshida discusses the philosophical approaches to the mask in Chapter Two of his forthcoming book, Avant-Garde Art and Non-Dominant Thought in Japan: Image, Matter, Separation (New York: Routledge, 2021).

I thank Tsujimura Makoto, Shimada Yoshiko, Erica Levin, Daniel Marcus, Elizabeth Ferrell, William Marotti, Rosemary Candelario, Bruce Baird, Anne McKnight, Emily Wilcox, and Max Woodworth for their help with this article.