Abstract: This article assesses the evidence for claims that the dropping of the atomic bombs were essential for securing Japan’s surrender and offers an alternative interpretation.

Keywords: Atomic bomb, Truman, Hirohito, Eisenhower, MacArthur, Stimson, Soviet Union.

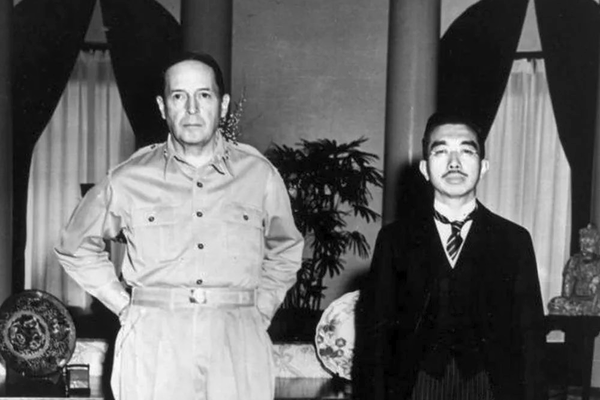

Gen. Douglas MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito, September, 1945

On September 2, 1945, V-J Day, Japanese officials aboard the USS Missouri formally surrendered to the United States, ending the Second World War.

Most Americans then and now believe that it was necessary for the U.S. to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in order to induce Japanese leaders to surrender. This is not what many U.S. military leaders believed at the time.

General Dwight Eisenhower, in his memoirs, recalled a visit from Secretary of War Henry Stimson in late July 1945: “I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of ‘face.’” Eisenhower reiterated the point years later in a Newsweek interview in 1963, saying that “the Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing.”1

In fact, seven out of eight top U.S. military commanders believed that it was unnecessary to use atomic bombs against Japan from a military-strategic vantage point, including Admirals Chester Nimitz, Ernest King, William Halsey, and William Leahy, and Generals Henry Arnold and Douglas MacArthur.2 According to Air Force historian Daniel Haulman, even General Curtis LeMay, the architect of the air war against Japan, believed “the new weapons were unnecessary, because his bombers were already destroying the Japanese cities.”3

One day after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, General MacArthur’s pilot, Weldon E. Rhoades, noted in his diary: “General MacArthur definitely is appalled and depressed by this ‘Frankenstein’ monster. I had a long talk with him today, necessitated by the impending trip to Okinawa.”4

Admiral Halsey, Commander of the U.S. Third Fleet, testified before Congress in September 1949, “I believe that bombing – especially atomic bombing – of civilians, is morally indefensible. . . . I know that the extermination theory has no place in a properly conducted war.”5

Admiral Leahy, Truman’s chief military advisor, wrote in his memoirs: “It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.”6

That the Japanese were on the verge of defeat was made clear to the president in a top-secret memorandum from Secretary of War Henry Stimson on July 2, 1945. Stimson noted that Japan “has no allies,” its “navy is nearly destroyed,” she is vulnerable to an economic blockade depriving her “of sufficient food and supplies for her population,” she is “terribly vulnerable to our concentrated air attack upon her crowded cities, industrial, and food resources,” she “has against her not only the Anglo-American forces but the rising forces of China and the ominous threat of Russia,” and the United States has “inexhaustible and untouched industrial resources to bring to bear against her diminishing potential.”

Stimson concluded that the U.S. should issue a warning of the “inevitability and completeness of the destruction” of Japan if it fails to surrender, adding, “I personally think that if in saying this we should add that we do not exclude a constitutional monarchy under her present dynasty, it would substantially add to the chances of acceptance.”7

Indeed, acceptance of Japan’s constitutional emperor was the main sticking point for Japan’s War Council, the six-person decision-making body over which Emperor Hirohito nominally presided. The council members were cognizant of Japan’s dire predicament but not necessarily ready to surrender unconditionally. They were split, three to three, between hawkish members seeking to get the most out of a peace agreement, to the point of maintaining Japanese control over parts of China, and dovish members inclined to give way on every condition but one, the preservation of the emperor.8

General MacArthur believed that Japan would have surrendered as early as May 1945 if the U.S. had not insisted upon “unconditional surrender.”9 MacArthur was appalled at the Potsdam Declaration, issued by the U.S., Britain, and China on July 26, which threatened “utter destruction” if Japan did not surrender unconditionally. As his biographer, William Manchester, wrote:

“He knew that the Japanese would never renounce their emperor, and that without him an orderly transition to peace would be impossible anyhow, because his people would never submit to Allied occupation unless he ordered it. Ironically, when the surrender did come, it was conditional, and the condition was a continuation of the imperial reign. Had the General’s advice been followed, the resort to atomic weapons at Hiroshima and Nagasaki might have been unnecessary.”10

Others appealed to the president to back off from his hard-nosed demand. Former president Herbert Hoover visited Truman on May 28, 1945, to argue that the best way to end the war quickly was to alter the terms of surrender. According to Hoover’s biographer, he told Truman, “I am convinced that if you, as President, will make a shortwave broadcast to the people of Japan – tell them they can have their Emperor if they surrender, that it will not mean unconditional surrender except for the militarists – you’ll get a peace in Japan, you’ll have both wars over.”11

There were, in fact, early drafts of the Potsdam Declaration that offered assurances of the emperor’s status, but these were nixed by Secretary of State James Byrnes, with whom Truman agreed. Members of General George Marshall’s staff argued in June 1945 that any clarification of the term “unconditional surrender” must be written in the form of “an ultimatum” and not in a way to “invite negotiation.” It was assumed that the American public was in favor of this inflexible position. Admiral Leahy, on the other hand, “said he could not agree with those who said to him that unless we obtain the unconditional surrender of the Japanese that we will have lost the war,” according to the June 18 meeting minutes.

“He [Leahy] feared no menace from Japan in the foreseeable future, even if we were unsuccessful in forcing unconditional surrender. What he did fear was that our insistence on unconditional surrender would result only in making the Japanese desperate and thereby increasing our casualty lists. He did not think this was at all necessary.”12

The impending entry into the war by the Soviet Union made Japan’s surrender all the more likely, according to a U.S.-British Combined Intelligence Estimate report on July 6. Commenting on this report in a letter to Prime Minister Winston Churchill, British General Hastings Ismay concluded that “when Russia came into the war against Japan, the Japanese would probably wish to get out on almost any terms short of the dethronement of the Emperor.”13

President Truman was well aware of this. At the Big Three meeting in Potsdam, Germany, Truman recorded in his journal on July 18, “Believe Japs will fold up before Russia comes in. I am sure they will when Manhattan [atomic bomb] appears over their homeland.” Truman also wrote to his wife that evening, “I’ll say that we’ll end the war a year sooner now, and think of the kids who won’t be killed.”14

As it was, the final Potsdam Declaration demanded that there “must be eliminated for all time the authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest,” and that a government must be “established in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people.” Japan’s War Council saw no ameliorating language in this declaration and thus rejected surrender.15

Truman subsequently gave the go-ahead for the atomic bombing of Hiroshima prior to Soviet entry. Notwithstanding a United Press report on August 8 stating that “as many as 200,000 of Hiroshima’s 340,000 residents perished or were injured,” he approved a second atomic bombing that obliterated Nagasaki on August 9.16

Japan’s War Council met on the evening of the 9th and agreed to surrender but with one condition: the emperor must be retained. Upon receiving Japan’s response, Secretary Byrnes was instructed to modify the original language to accommodate the Japanese condition. The document thus read: “the authority of the Emperor . . . shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers.” The emperor, as such, would retain his symbolic authority under U.S. rule. This simple change made the proposal acceptable to both sides.

On August 15, Emperor Hirohito gave a radio address to the Japanese people announcing that Japan would “effect a settlement of the present situation,” accepting defeat. In hindsight, Japan’s surrender could likely have been achieved earlier, without the atomic bombings, on precisely the terms that the U.S. eventually accepted, allowing the emperor to “retain his symbolic authority under U.S. rule.”

Truman would later claim that “half a million American lives” were saved by the atomic bombings in lieu of a U.S. invasion of the Japanese mainland. This framing was disingenuous, however, as it omitted the real possibility of ending the war by altering the terms of surrender, a third option that was eventually chosen.

The diplomatic option was certainly the most humane and deserved priority. It was also the most realistic. The U.S. would seek the emperor’s blessings along with the cooperation of Japanese officials, agencies, and citizens in order to exercise the authority of the Allied Occupation over Japan in the aftermath of the war.

The assertion that the atomic bombings forced Japan to surrender was not supported by a U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, published in July 1946, which noted that the decision of Japanese leaders “to abandon the war is tied up with other factors. The atomic bomb had more effect on the thinking of government leaders than on the morale of the rank and file of civilians outside the target areas. It cannot be said, however, that the atomic bomb convinced the leaders who effected the peace of the necessity of surrender.”17

Admiral King, Commander in Chief of Naval Operations, stated in his memoirs that neither the atomic bombings nor a prospective U.S. invasion of the Japanese mainland was necessary, as “an effective naval blockade would, in the course of time, have starved the Japanese into submission through lack of oil, rice, medicines, and other essential materials.”18

Four factors may be seen to have contributed to Japan’s surrender: (1) the gradual impoverishment of the Japanese people and withering of Japan’s military potential under the U.S. conventional war, which included a blockade and air attacks that destroyed 64 Japanese cities prior to the atomic bomb; (2) the dropping of two U.S. atomic bombs on August 6 and 9; (3) the advance of Soviet forces and their intervention on August 8; and (4) the discrete acceptance in Washington of Japan’s “conditional” terms of surrender on August 9. The argument in this essay is that the latter was key and could have been achieved weeks or months earlier, thereby obviating the “need” for both the U.S. atomic bombings and Soviet entry into the war.

In the aftermath of the atomic bombings, the Truman administration hid their true nature and effects. In a radio address to the nation on August 9, 1945, the president claimed that “the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a military base. That was because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians.”19

This was not why Hiroshima was chosen. Rather, the city was selected because it was “the largest untouched target not on the 21st Bomber Command priority list,” according to the administration’s Target Committee.20 Hiroshima, in other words, did not have enough military production to justify an earlier conventional attack (as compared to other cities on the priority list), and the effects of the bomb had to be uncontaminated from previous bombings in order to properly assess their damage.

Secondly, Truman and company offered no hint of the deadly, long-lasting effects of nuclear radiation. On September 13, more than one month after the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, the New York Times published a front-page article titled, “No Radioactivity in Hiroshima Ruins.” The article noted that Brigadier General T. F. Farrell, chief of the War Department’s atomic bomb mission, “denied categorically that it [the Hiroshima bomb] produced a dangerous, lingering radioactivity in the ruins of the town.” After visiting the site, Farrell, a former New York State engineer, “said his group of scientists found no evidence of continuing radioactivity in the blasted area on September 9 when they began their investigations.” He added that “there was no danger to be encountered by living in the area at present.”21

A third, more lasting deception was that the atomic bombs were dropped “in order to save the lives of thousands and thousands of young Americans,” as Truman said on August 9, which presumed that the bombings had forced the Japanese surrender and thus mitigated the need for an invasion.

“Revisionist” scholars have long challenged Truman’s claim, arguing that the president’s main motivation was to send a message to Moscow and thwart Soviet influence in Asia and elsewhere.22 Evidence for this thesis relies mainly on commentary by U.S. officials.

Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, for example, recorded in his diary that Secretary Byrnes was “most anxious to get the Japanese affair over with before the Russians got in.” Atomic scientist Leo Szilard, in reporting on his meeting with Byrnes on May 28, 1945 (five weeks before Byrnes became secretary of state), noted that Byrnes “did not argue that it was necessary to use the bomb against the cities of Japan in order to win the war.” Rather, he held “that our possessing and demonstrating the bomb would make Russia more manageable in Europe.”23

This was also the view of Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov who believed that President Truman wanted to shock the Soviets in order “to show who was boss.” The atomic bombings, he contended in his memoirs, “were not aimed at Japan but rather at the Soviet Union. They said, bear in mind you don’t have an atomic bomb and we do, and this is what the consequences will be if you make the wrong move.”24

Still, one must ask, if Truman’s primary motivation was to thwart Soviet designs in Asia, why wouldn’t he make every effort to conclude a peace treaty with Japan before the Soviet Union entered the war, adjusting the terms of Japan’s surrender to suit. The U.S., as such, would have gained significant geopolitical advantages vis-à-vis the Soviet Union, including full control of Korea, while also obviating the “need” for either atomic bombs or a U.S. invasion.

Indeed, Japan had put out peace feelers. As reported in the New York Times on July 26, 1945, “The Tokyo Radio, in an English-language broadcast to North America, has urged that the United States adopt a more lenient attitude toward Japan with regard to peace.” The broadcast quoted an ancient Aesop Fable in which a powerful wind could not force a man to give up his coat, but a gentle warming sun succeeded in doing so.25

Japan’s appeal fell on deaf ears in Washington. Truman, like many Americans, believed that Japan deserved no leniency. As he said in his August 9th radio address, “Having found the bomb, we have used it. We have used it against those who attacked us without warning at Pearl Harbor, against those who have starved and beaten and executed American prisoners of war, against those who have abandoned all pretense of obeying international laws of warfare.”

This was the language of vengeance, retribution, and punishment. The decision to use the bomb was also impelled by a kind of technological imperative to use the latest weapons developed; by a desensitization to mass violence, exhibited in the firebombing of enemy cities; by a dehumanizing racism against the Japanese that extended from the war front to the home front where 120,000 Japanese American citizens were interned throughout the war; and by an overall war mentality that hailed military victory and “unconditional surrender” and downplayed diplomacy. Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy later wrote that “everyone was so intent on winning the war by military means that the introduction of political considerations was almost accidental.”26

Truman made his decision to use the atomic bomb in less than three weeks following the successful test in New Mexico on July 16. He failed to grasp the geopolitical advantages of altering the terms of surrender to secure surrender prior to Soviet entry into the war. He disregarded General MacArthur’s advice that allowing the emperor to remain would enable the U.S. to better manage Japan’s postwar reconstruction. In the end, he reciprocated Japanese atrocities during the war with a greater American atrocity.

Notes

Dwight Eisenhower, Mandate for Change (New York: Doubleday, 1963), 380; and “Ike on Ike,” Newsweek, November 11, 1963.

Oliver Stone and Peter Kuznick, The Untold History of the United States (New York: Gallery Books, 2019), 176-77. See also Sidney Shalett, “Nimitz Receives All-Out Welcome from Washington,” New York Times, October 6, 1945; H. H. Arnold, Global Mission (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1949), 598; and other primary sources noted below.

Daniel L. Haulman, “Firebombing Air Raids on Cities at Night,” Air Power History, Vol. 65, No. 4 (Winter 2018), 41.

Weldon E. Rhoades, Flying MacArthur to Victory (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1987), 429.

Testimony of Admiral Halsey, September 8, 1949, File: “Congressional Hearings 1949-57,” Box 35, Halsey Papers, Library of Congress.

Stimson memorandum to The President, “Proposed Program for Japan,” 2 July 1945, Top Secret, pp. 3-6 (Source: Naval Aide to the President Files, box 4, Berlin Conference File, Volume XI – Miscellaneous papers: Japan, Harry S. Truman Presidential Library), National Security Archive Briefing Book #716.

Richard B. Frank, “To Bear the Unbearable”: Japan’s Surrender, Part II,” The National WWII Museum, August 20, 2020.

Walter Trohan, a reporter for the Chicago Tribune, reported that two days before President Roosevelt left for the Yalta conference with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin in early February 1945, he was shown a forty-page memorandum drafted by General MacArthur outlining a Japanese offer for surrender almost identical with the terms later concluded by President Truman. Trohan related that he was given a copy of this communication by Admiral William Leahy who swore him to secrecy with the pledge not to release the story until the war was over. Trohan honored his pledge and reported his story in the Chicago Tribune and the Washington Times-Herald on August 19, 1945. Cited in John J. McClaughlin, “The Bomb Was Not Necessary,” History News Network (2010).

Richard Norton Smith, An Uncommon Man: The Triumph of Herbert Hoover (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1984), 347. In early May 1946, while on a tour of the Pacific, former President Herbert Hoover met with General Douglas MacArthur alone for several hours. Hoover recalled: “I told MacArthur of my memorandum of mid-May 1945 to Truman, that peace could be had with Japan by which our major objectives would be accomplished. MacArthur said that was correct and that we would have avoided all of the losses, the atomic bomb, and the entry of Russia into Manchuria.” Herbert Hoover Diary, 1946 Journey, May 4, 5, 6, 1946, Post-Presidential Papers, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library.

“Minutes of meeting held at the White House on 18 June 1945 at 1530 hours,” Truman Library; also contained in Foreign Relations of the United States, Diplomatic Papers: The Conference of Berlin, 1945 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1960), 909; and Rufus E. Miles, “Hiroshima: The Strange Myth of Half a Million American Lives Saved.” International Security 10, no. 2 (1985): 127.

Gar Alperovitz, Robert L. Messer and Barton J. Bernstein, “Marshall, Truman, and the Decision to Drop the Bomb,” International Security, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Winter, 1991-1992), 210-11. At the request of the U.S., Soviet leader Joseph Stalin agreed to enter the war against Japan three months after the end of the war in Europe (May 8). The Soviet Union did so at the appointed hour, sending a massive invasion force to take over the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo (Manchuria). Over the next few weeks, almost 600,000 Japanese soldiers surrendered to Soviet forces in Manchuria, Sakhalin and the Kurile chain. See Mark Ealey, “An August Storm: the Soviet-Japan Endgame in the Pacific War,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 4, Issue 2 (February 16, 2006).

The United Press Report is quoted in Alex Wellerstein, “Counting the Dead at Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, August 4, 2020. The actual number killed in Hiroshima by the end of 1945 was about 140,000, according to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons.

The United States Strategi Bombing Survey: The Effects of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, June 30, 1946 (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1946), page 22. The historian Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, in Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2005), makes a strong case, based on careful reading of Japanese documents, that Soviet entry into the war rather than the dropping of the two nuclear bombs was decisive in compelling Japan’s surrender. He did not convince reviewer Marc Gallicchio, however, who wrote, “It seems safer to conclude that the nuclear bombs and the impact of the Soviet invasion were too closely intertwined for historians to disentangle them as neatly as Hasegawa implies.” Marc Gallicchio, “Review Works: Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan by Tsuyoshi Hasegawa,” Journal of Cold War Studies, Vol, 9, No. 4 (Fall 2007), 170.

Ernest Joseph King and Walter Muir Whitehill, Fleet Admiral King, A Naval Record (New York: W.W. Norton, 1952), 621.

President Harry S. Truman, “August 9, 1945: Radio Report to the American People on the Potsdam Conference,” University of Virginia Miller Center Presidential Speeches.

“Notes on the Initial Meeting of the Target Committee [held April 27, 1945],” (2 May 1945), in Correspondence (“Top Secret”) of the Manhattan Engineer District, 1942-1946, microfilm publication M1109 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1980), Roll 1, Target 6, Folder 5D, “Selection of Targets”; cited in Alex Wellerstein, “The Kyoto misconception,” The Nuclear Secrecy Blog, August 8, 2014.

W. H. Lawrence, “No Radioactivity in Hiroshima Ruin,” New York Times, September 13, 1945, page 1.

See, for example, Gar Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb (New York: Vintage Books, 1995); and Peter Kuznick, “The Actual Reason Why America Dropped 2 Atomic Bombs on Japan,” YouTube video.

James V. Forrestal, The Forrestal Diaries (New York: Viking, 1951), 78, cited in Alperovitz, Messer and Bernstein, “Marshall, Truman, and the Decision to Drop the Bomb,” 212-213; and Paul Ham, “Did the Atomic Bomb End the Pacific War? – Part 1,” History News Network, August 2, 2020.

V. M. Molotov, Molotov Remembers: Inside Kremlin Politics, edited by Albert Resis (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1993), 55, 58.

John McCloy, The Challenge to American Foreign Policy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1953), 42. See also, John W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War (New York: Pantheon Books, 1986); Mark Selden, “A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities & the American Way of War from World War II to Iraq,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 5, Issue 5, May 2, 2007, reprinted in Yuki Tanaka and Marilyn B. Young, eds., Bombing Civilians: A Twentieth Century History (New York: The New Press, 2009).