Abstract: This paper will present a timeline of how a remote island in the South Pacific became a U.S. appurtenance (1860); then a U.S. territory (1925); and, finally, through a so-called “friendship treaty,” bargained away by New Zealand in order to maximize American Sāmoa’s maritime boundaries (1980). The original claim to the island is fraudulent, as many government officials and scholars have long suspected but have been unable to prove. This paper will examine the fraud in detail and present conclusive evidence for the first time. The island’s name is Olohega [oloˈhɛŋa] and it belongs geographically, historically, and culturally to the nation of Tokelau.

Keywords: Tokelau, Olohega, Swains Island, Guano Islands Act, William W. Taylor, U.S. Guano Company, Wilkes Expedition, John W. Norie, U.S. Department of State, U.N. Special Committee on Decolonization, New Zealand, Treaty of Tokehega, U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, Aliki Faipule Kolouei O’Brien

Figure 1. Astronaut’s photograph of Tokelau’s three atolls from space:

(bottom to top) Atafu, Nukunonu, and Fakaofo.

The group’s fourth island, Olohega, is out of frame.

(Courtesy of NASA Johnson Space Center)

Since the mid-1800s, the remote nation of Tokelau has been denied its fourth island. Tokelauans call it Olohega.1 The island is not easily accessed physically or politically. Outside of Oceania, most people are unaware of its existence or why Olohega is at the center of an ongoing (if sometimes dormant) international dispute involving the United States, New Zealand, and Tokelau.

Olohega (also Olosega or Olosenga) is identified in contemporary charts as Swains Island. Politically, the island is a U.S. territory by way of American Sāmoa and privately owned by one family. Geographically, the island belongs to the Tokelau group, located north of the Sāmoan archipelago. The group is comprised of four islands; the Preamble of the Constitution of Tokelau records their names as Atafu, Nukunonu, Fakaofo, and Olohega.2

In 1859, all four islands were fraudulently claimed by a U.S. citizen. In 1980, the U.S. finally renounced its claim to three of the islands to Tokelau by treaty, but only at the expense of the territorial abandonment of the fourth island, Olohega. There is little coincidence that the 220-mile distance from American Sāmoa’s main island, Tutuila, and the territory’s northernmost island, Olohega (Swains), is approximate to the outward limit of a lucrative maritime boundary called an exclusive economic zone (EEZ). “The Question of Olohega” is fundamentally a question for the 21st century after 160 years of injustice: How did one island in the South Pacific take on so much importance, and why hasn’t the initial fraud ever been tested in a court of law?

Figure 2. Detail of 1922 Bartholomew map showing territorial boundaries and ocean steamer routes.

By an act of Congress in 1925, Tokelau’s southernmost island became American Sāmoa’s

northernmost island, known as Swains in the charts. (Courtesy of David Rumsey Map Collection)

The Legal Instrument

The legal instrument used to justify the taking of Olohega and numerous other Pacific and Caribbean islands is called the U.S. Guano Islands Act of 1856. Islands claimed under the act are generically referred to as “guano islands” (an offensive term once all the facts are examined).

The act (codified at Title 48 of the U.S. Code) superficially allows U.S. citizens to claim uninhabited islands that contain deposits of guano. According to historian Jimmy M. Skaggs, the act is a unique legal arrangement with “no parallel in history.” In his estimation, “Even Great Britain…never granted such extraordinary power as territorial aggrandizement to individual private citizens.”3

The taking of islands by U.S. citizens, each claim a seemingly small act of appropriation, started a sequence of events that has yet to lose momentum.4 As a result, Pacific Islanders are denied political agency in their own affairs. There is no greater example than Olohega, and a review of the contemporary consequences of U.S. guano islands is long overdue. Olohega, measured against the act’s requirements, never qualified as a “guano island.”5 The original claimant, as many have suspected, committed fraud. Even with evidence, it may be difficult to reverse Olohega’s many accretive territorial designations. This is the true legacy of the Guano Islands Act of 1856.

Original Claim

The original claim to Olohega is based on a fraud committed by Captain William W. Taylor, a whaler from South Dartmouth, Massachusetts, in 1859.6 From the outset, U.S. government officials had their doubts about the legitimacy of his claim to Olohega and 42 other islands under the Guano Act, but no meaningful action was ever taken. Over the years, journalists and researchers specializing in American territorial expansion in the Pacific have been equally skeptical, but none, thus far, have been able to present hard evidence of fraudulent claim.

Historians Roy F. Nichols and Jimmy M. Skaggs have conjectured that Taylor had found his islands in “old, inaccurate charts,” rather than firsthand encounters at sea.7 An important distinction because Taylor swore in a signed affidavit he believed all 43 islands contained “large quantities of guano,” with many in possession of “good harbors” and “fresh water.” He also swore none of the islands were inhabited. Those descriptions imply some degree of empirical familiarity, but modern cartography (and what can be known anthropologically) leave little doubt he found his islands through the cold calculus of charts.8 But which charts?

The search for evidence as to how Taylor made his island discoveries could conceivably matter; the annexation of Olohega and the continued private ownership of the island is predicated on the legitimacy of his claim under the Guano Islands Act.9 By closely analyzing Taylor’s original affidavit and comparing the data to one particular chart, the details of his fraud can finally be substantiated.

Together with new evidence is the residual question of whether it is too late for Tokelauans to press their case for the repatriation of Olohega. In 1979, Tokelauans were dissuaded from pursuing the matter and told their “claim to Olohega was weak and would not succeed in an international tribunal.”10 A year later, Tokelau’s administering power, New Zealand, negotiated a delimitation treaty with the U.S. that firmly places Olohega on the American Sāmoa side of the maritime boundary. In truth, the weak claim to Olohega rests with the U.S., though it has yet to be tested in an international court of law.

While international law has historically favored the territorial claims of “civilized nations” over indigenous peoples, Swiss jurist Max Huber’s intertemporal rule of 1928 seems particularly relevant in the case of Olohega:

…a juridical fact must be appreciated in the light of the law contemporary with it, and not of the law in force at the time when a dispute in regard to it arises or falls to be settled.11

In other words, “a law does not work backwards.” Under the Huber rule, the validity of the U.S.’ territorial claim to Olohega doesn’t begin and end with the 1980 treaty New Zealand negotiated on Tokelau’s behalf; the legal challenge begins (and perhaps ends) with an examination of Capt. William W. Taylor’s claim to all four of Tokelau’s islands in 1859 under the Guano Islands Act—an act that has been described by legal experts through the years as “nebulous in international law.”

Figure 3. Aerial view of Olohega and its signature lagoon in 1961.

The lagoon is closed to the sea and contains freshwater.

For this reason, some coral experts consider it to be a “low island,” rather than a true atoll.

NOAA refers to Olohega as the “freshwater jewel of the South Pacific.” (U.S. Geological Survey)

Original Purpose

The original purpose of the Guano Islands Act of 1856 was to provide American entrepreneurs direct access to guano (i.e., bird droppings) to be sold exclusively to U.S. citizens at a reasonable, fixed rate. Due to a rich oceanic diet, the guano produced by seabird colonies proved to be an effective soil revitalizer for exhausted agricultural lands. The best and most plentiful deposits, however, were found on arid, isolated islands—islands located far from the continental United States at or near the equator.12 Under the authority of the act, ambitious U.S. merchants, with the help of “their sea-captain friends,” claimed as many of these islands in the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea as the U.S. Department of State would allow: In total, 71 islands, rocks, and keys were bonded between 1856 and 1884.13

The 165-year-old law, which remains in effect, is simplistically worded, yet complicated in its potential for misuse. The most significant misinterpretation of the Guano Act is that it legalizes the taking of islands by U.S. citizens, which, in turn, provides legal justification for annexation of “guano islands” by the federal government. A close reading of both the originating act and revised law makes clear this is not the case.14 The law, as written, “is based on the discovery not of the island or other place named, but of the deposit of guano.”15

Accordingly, the discoverer acquires “the exclusive right of occupying said islands, rocks, or keys, for the purpose of obtaining guano,” with possession of a place considered a temporary arrangement lasting for the duration of mining operations. For this reason, the act includes an abandonment clause that specifies that once the guano has been removed, there is nothing “obliging the United States to retain possession of said islands, rocks, or keys.”16

The abandonment clause exemplifies the nebulous and noncommittal nature of the act. The legislators who argued over the final bill in the summer of 1856 were cognizant they were deviating from norms in public law by conferring title (however temporary) to an individual discoverer rather than “to the nation under whose flag it is discovered.”17 Senator William Henry Seward, the bill’s sponsor, argued that the islands in question were intrinsically undesirable and the compulsion to retain them nil:

…the bill is framed so as to embrace only these more ragged rocks, which are covered with this deposit in the ocean, which are fit for no dominion, or for anything else, except for the guano which is found upon them. There is no temptation whatever for the abuse of authority by the establishment of colonies or any other form of permanent occupation there…The bill itself then provides that whenever the Guano shall be exhausted, or cease to be found on the islands, they should revert and relapse out of the jurisdiction of the United States.18

Seward’s argument is a cogent explanation for why a qualifying island under the act is one that is unclaimed, uninhabited, and covered in guano. While the act specifies the discoverer must provide the State Department “satisfactory evidence” that an island has met that criteria, there has never been an evenly applied method to verify claims beyond a claimant’s word. In the case of Capt. Taylor’s claim, he swept up islands outside the bounds of Seward’s simple calculus and the consequences endure to this day.

Taylor’s Affidavit

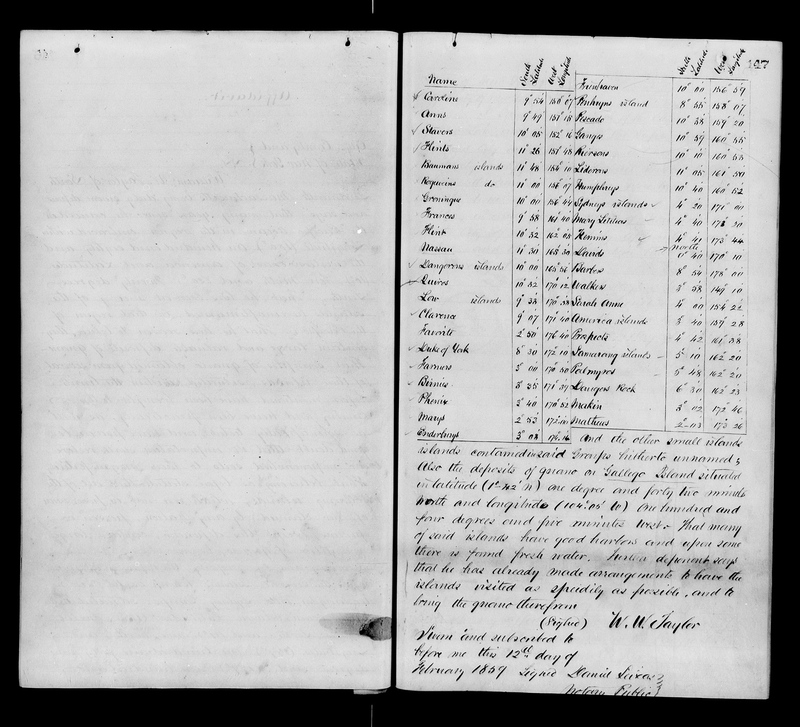

When Capt. Taylor submitted his affidavit of discovery in 1859, he furnished all the prerequisite information as required by the act.19 The wording of the document also demonstrates a clear and mutual understanding with government officials that he is claiming deposits of guano as private property, not the islands per se. An excerpt from his handwritten affidavit reads (Fig. 4):

That believing as before stated that all of the following islands, which are not in possession of, nor claimed by any Nation, person or persons, except this deponent [William W. Taylor], contain large quantities of guano, he now claims as his discovery and his property, the deposits of guano upon the several islands known as the Caroline, Washington and Sydney Groups.20

Figure 4. Excerpt from Taylor’s affidavit of discovery. (U.S. State Department)

His claim, then as now, is irredeemably flawed. Of Taylor’s claim to guano deposits on 43 islands, only 21 islands actually exist. Of the 21 islands that exist, 10 were known at the time to be inhabited by Pacific Islanders; one island is located in a region of high rainfall where substantive amounts of guano do not accumulate; and one island, a low-lying reef, is largely submerged by rolling breakers, therefore unsuitable for sustaining seabird colonies or human enterprise.21 Despite these numerous deficiencies, the State Department certified the entirety of Taylor’s claim in 1860.22

As a result of State Department certification, all the island names and coordinates recorded in Taylor’s affidavit were assimilated into an official list published by the Treasury Department. This official list, printed under the heading “Guano Islands Appertaining to the United States,” continues to exert influence in legal affairs, particularly in the case of Olohega. Places in the Pacific are seemingly easy to take on paper (for Western nations), as Taylor’s claim attests, but they are difficult, if not impossible, to restore as matters of modern-day diplomacy. More than “fly-specks upon the map,” each of Taylor’s existent islands is a valuable ecosystem within discreet geographical and anthropological groupings defined by the peregrinations of ocean peoples and the perennial return of seabirds and turtles to the precise spot where they were born or imprinted upon.23

Claiming ‘Islands in a Far Sea’

In Taylor’s signed affidavit, dated February 12, 1859, he supplied the State Department with a handwritten list of islands and their geographical coordinates in the “Caroline, Washington and Sydney Groups.” Olohega appears as Quiros, a name predating Swains, which he placed in latitude 10° 32′ S., longitude 170° 12′ W.24 Tokelau’s three other islands also appear in the list. Two are recorded under the Anglocentric names of Duke of York and Clarence, with the third listed as Low Islands.25 Taylor’s inclusion of all four islands of the Tokelau group proved consequential in treaty negotiations between the U.S. and New Zealand in 1980.

Figure 5. Taylor’s original list of islands included in his affidavit of discovery,

dated Feb. 12, 1859. (U.S. State Department)

As Skaggs and other historians have pointed out, Taylor’s motivation in capturing as many islands as possible “was probably influenced by his desire to sell his interest to the United States Guano Company.” Taylor, in fact, assigned his rights to the guano deposits on all 43 islands to Alfred G. Benson’s U.S. Guano Co. in 1859.26 The deed is notarized the same day as Taylor’s affidavit and by the same notary public, which suggests they were active collaborators.

There is also a letter that accompanies Taylor’s affidavit that is both a character study and a clue to the precipitating event that instigated the massive claim. Taylor’s letter, addressed to Secretary of State Lewis Cass, is an impassioned plea to approve the submitted claim posthaste and includes a news clip from a recent morning paper that “shows France has already taken possession of one island [and]…is looking for others.” The inclusion of the article provides an entry point for Taylor to apply pressure (and insert a veiled threat). He informs Cass:

…there is also good reason to believe that an American citizen has recently gone to Europe for the purpose of disclosing to someone of those Governments the existence of large deposits of guano on one or more of the very islands now presented to your consideration and which I beg to request [my claim] may be officially announced to the world as American property.27

Benson applied his own brand of pressure by pre-emptively announcing in the New-York Daily Tribune in early March that the U.S. government had recognized the claim, even though it had been less than a month since Taylor had submitted his affidavit.28 For all the manipulation, the claim did not receive the State Department’s imprimatur until 1860. Benson’s ploy of publishing the names of Taylor’s islands and their positions in a major newspaper might have worked to future-proof the claim among business rivals, but this “new” influx of information also caught the attention of legitimate publications around the world, and there were doubts.

Inhabited Islands

While Benson’s company filed the formal paper work with the State Department and provided the surety bonds as required by the act ($100,000), it was Taylor who signed the affidavit of discovery and supplied the list of island names and coordinates.29 As a shipmaster who had led whaling expeditions in the Atlantic, South Seas, and Indian Ocean between 1840-1853, Taylor conferred authenticity to the enterprise—at least superficially.30

The first public indications that Taylor and the U.S. Guano Co.’s claim was less than perfect, but not necessarily fraudulent, came within months of submitting his affidavit to the State Department. One article appeared in a German-language journal for geographers in May. In September, another article published in a British magazine for professional seafarers. Both articles questioned the existence of several islands in Taylor’s list. And both identify islands known to be inhabited, which meant under the act, “possession of them cannot very well be taken by foreigners.”31 The State Department—either unaware or uninterested in what other nations were writing in regard to the claim—accepted the surety bond for all 43 islands on February 8, 1860.32 Acceptance of the bond signified that the requirements of the act had been fulfilled to the government’s satisfaction; the islands now “appertained to the United States.”

Taylor’s first deception is in claiming nonexistent islands, but the more damning deception is in claiming those places known to be inhabited. In Taylor’s time, charting the Pacific Ocean remained in a state of flux (though improving with the use of chronometers). This ambiguity worked in his favor. The more important question regarding Taylor’s claim is how difficult would it have been in the late-1800s to early-1900s for the State Department to ascertain which islands were inhabited.33

The answer is straightforward. If officials had been inclined, there were plenty of publicly available sources to verify his claim (Table 1). Ten islands included in Taylor’s affidavit of discovery were reported inhabited by Pacific Islanders by a variety of credible sources at regular intervals between 1844 and 1862. In the case of Olohega, the sources are set within missionary work and would not have been as accessible as the others.34 By 1925, the New Zealand administration formally knew Tokelauans claimed Olohega as their island, “but this was largely ignored.”35

Table 1. Inhabited islands included in Taylor’s list.

One island was annexed to a U.S. territory in 1925 and seven others were formally relinquished

through “friendship treaties” in the late 20th century. (Table by the author)

Of the 21 islands on Taylor’s list that actually exist, none were ever occupied or mined by his assignee, the U.S. Guano Co. Almost half of the 21 islands were inhabited by Pacific Islanders and should have never been claimed (let alone bonded) under the Guano Islands Act. It would take until the late-1970s for the United States to begin treaty negotiations in preparation for their return.36 Of the 10 inhabited islands, the U.S. renounced sovereignty claims to seven by formal treaty: four atolls were relinquished in favor of the Cook Islands and three atolls relinquished in favor of Tokelau. The legal basis for why Tokelau’s fourth island, Olohega, has not been repatriated begins with the following rationale: “It is included in the list.”

List as Legal Pretext

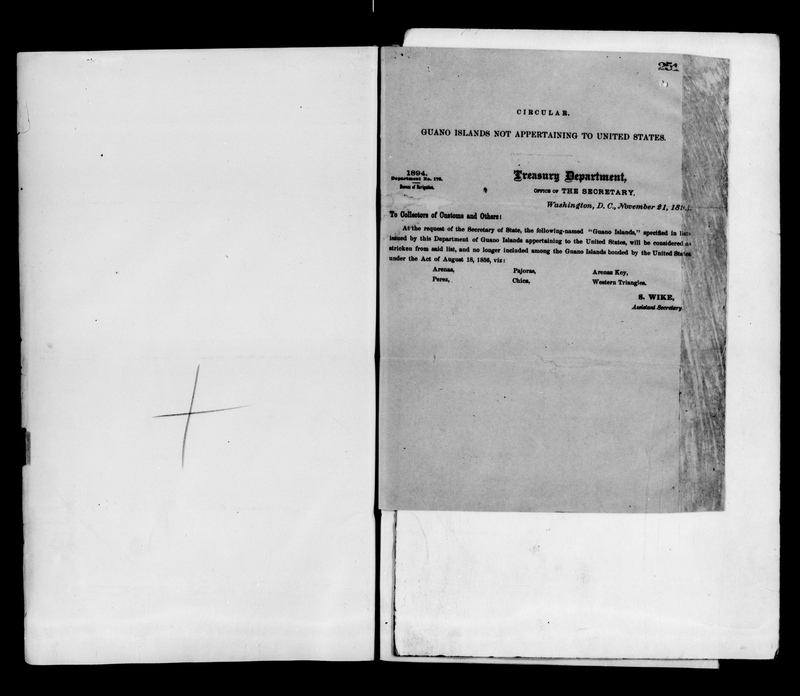

Taylor’s list of islands included in his affidavit of discovery still has currency in legal matters, specifically in the settling of sovereignty disputes. The list’s longevity in legal affairs is due to: (1) the State Department’s uncritical review of Taylor’s claim, and (2) the Treasury Department’s subsequent inclusion of all 43 islands in an official list of bonded claims. The official list, published as a circular issued by the Secretary of the Treasury, was sent to the Collector of Customs at regular intervals between 1867 to 1902.37 Customs relied on the list as a practical matter: vessels conveying guano from the islands listed were exempted from import levies. While it could be argued that the inclusion of Taylor’s islands (both existent and nonexistent) in the official list was of little consequence since guano from those places never made it to U.S. ports, the list has often been used to establish ownership by individual claimants as well as the U.S. government.

The number of islands, rocks, or keys on the Treasury Department’s list fluctuated, with revision favoring addition rather than subtraction. In 1867, the department recorded bonds on file for 58 places. By 1885, the number had increased to 71. And on two occasions, in 1867 and 1894, places were deleted from the list due to sovereignty disputes; proof that islands could be “struck from the list” if the State Department showed a willingness to capitulate to the objecting country.38

In regard to Taylor’s claim, the names and coordinates of all 43 islands were reproduced in facsimile to his original affidavit in every single official list; a case in point that it was easier for his nonexistent islands to remain on the list than for countries with valid sovereignty claims to have their islands struck from it.

Figure 6. Circular, “Guano Islands Not Appertaining to United States,” sent to the Treasury Dept.

with instructions for islands to be “stricken from the list,” dated Nov. 21, 1894. (U.S. State Department)

The most consequential example of the legal use of the official list appears in the opening paragraph of a House Joint Resolution, which led to Olohega’s annexation in 1925: “Swains Island (otherwise known as Quiros, Gente Hermosa, Olosega, and Jennings Island) is included in the list of guano islands appertaining to the United States, which have been bonded under the Act of Congress approved August 18, 1856.”39

Inclusion in “the list” is the first of two justifications for Olohega’s annexation to the U.S. territory of American Sāmoa, despite the fact that Taylor and his assignee, the U.S. Guano Co., had failed to meet critical statutory requirements of the Guano Act. The claim’s deficiencies are spelled out in a State Department memorandum from the Office of Legal Counsel from 1932:

As with most of the other islands on Captain Taylor’s list, there is no evidence that Captain Taylor ever landed on the island [Olohega] or in fact discovered guano there; and there is no evidence that guano was ever taken from the island or that it was occupied under the Guano Act by the discoverer or by any of his assigns.40

If the State Department had arrived at this assessment of Taylor’s claim in 1859, rather than in 1932, the question of Olohega might have been resolved quite differently. Analogous to how “the list” is used to establish legal justification for annexation in 1925, the act of annexation is used as justification for maintaining the status quo of Olohega as a U.S. Territory.

The second reason given for annexation in the House Joint Resolution is based on the occupation of the island by a U.S. citizen from Shelter Island, New York, named Eli Jennings, who arrived there sometime in the 1850s.41 (The private ownership of the island is both complicated and contentious and will be the subject of a second paper.) In short, there is no evidence that either Taylor or Benson knew Jennings or had any kind of business arrangement with him, which makes it strange from a legal point of view that the resolution, in an effort to establish American provenance, conjoins the history of Olohega as a bonded (yet never occupied) “guano island” to the unauthorized occupation and operation of the island as a coconut plantation.42

Final Word on Lists

One final word on the legitimacy of “the list” in this section. Inclusion in the list means little more than there were bonds on file with the Treasury Department, sent over from the State Department. The compiler and publisher of the list had no hand in ascertaining whether each bonded claim qualified as a “guano island appertaining to the United States,” as explained in a typewritten communique to the State Department from the Comptroller of the Treasury, R. B. Bowler, in 1894 (Fig. 7).43

Figure 7. Comptroller of the Treasury R. B. Bowler’s response to the State Dept.

regarding “the list,” dated Nov. 28, 1894. (U.S. State Department)

By Bowler’s time, places on “the list” had become empty signifiers in a positive feedback loop. Many of the bonds on file were no longer valid, yet island names remained in print for decades.44 An important point because it has been assumed over these years that if an island had been bonded and appeared in the official list, it represents a transferable title, which it doesn’t.45

Given the State Department’s poor record of evaluating the legitimacy of claims and grooming the official list accordingly, the legal value of “the list” is questionable. In Taylor’s case, not only did many of the islands not exist, but many of them had no guano, and, more significant, many of them were ineligible for inclusion because they had resident populations. Even into the 1930s, the State Department still wasn’t 100 percent sure where Taylor had obtained his information or how many islands in his list were real or imagined.

The Norie Chart

Capt. Taylor’s compromised claim is the cause of a diplomatic crisis that has been brewing since the early 20th century. Now, after 162 years, the origin of Taylor’s claim to 43 islands can finally be substantiated. He took the islands from John W. Norie’s New Chart of the Pacific Ocean, published in 1836. By comparing the island names and coordinates included in his affidavit of discovery to this particular Norie chart, the evidence is clear (and Taylor’s intention to commit fraud unambiguous).

Figure 8. Taylor’s islands were taken from the Norie chart of the Pacific Ocean, published in 1836.

White flags indicate those islands Taylor listed in his affidavit of discovery.

(Courtesy of the David Rumsey Map Collection, annotated by the author)

One reason Taylor’s claim has remained an impenetrable cipher into the modern era can be attributed to the perpetual rearrangement of the official list of “guano islands” in books, articles, and Wikipedia entries. As one example, when the claim is incorporated into an alphabetized compilation of all bonded U.S. claims (including those located in the Caribbean), it is difficult to track Taylor’s movements “at sea” or across a chart. Returning to the original arrangement of islands as they appear in his affidavit of discovery is the first step in breaking the code.46

The graphic below is a side-by-side comparison of island names taken from the Norie chart and Taylor’s handwritten affidavit (Fig. 9). All but three of Taylor’s islands can be found in the chart.47 The few spelling differences that exist between the names in the chart and the handwritten affidavit can be plausibly chalked up to poor eyesight (e.g., Tienhoven/Freinhaven); transposition (e.g., ei/ie and ie/ei); and preference for American spelling of the same word (e.g., Favourite/Favorite).

Figure 9. Island names and other notations in the Norie Chart of 1836 (left)

compared to names in Taylor’s affidavit of discovery (right). (Graphic by the author)

Figure 10. Numerical order of Taylor’s islands relative to their location in the Norie chart.

Islands marked with an asterisk appear in his affidavit but not the chart. (Graphic by the author)

A comparison of coordinates between the Norie chart and Taylor’s list is a more involved process, and is included as Appendix 1. In summary, the named islands are found at the approximate latitude and longitude in the Norie chart as those positions provided to the State Department (there are five outliers, all duly noted). The most compelling evidence that Taylor “discovered” his islands in this particular chart is found in the exactitude of names and positions he provided for nonexistent islands, which account for over half his claim.

When Taylor submitted his affidavit of discovery in 1859, the chart he used had been around for a few decades. In the 1850s, the hydrographic charts of the Wilkes Expedition were among the most authoritative and would have been readily available to the State Department had it been inclined to evaluate claims (suspicious or otherwise). In the realm of Pacific hydrography, the accomplishments of the Wilkes-led United States Exploring Expedition were not in island “discoveries” per se but in a reductive process of establishing the “non-existence or identity of numerous doubtful islands” using highly scientific methods and instrumentation.

In the final analysis, Taylor chose the chart that had the most islands. He wasn’t interested in geographical accuracy, sovereignty issues, or the long-term foreign policy implications of U.S. guano island claims, but neither was the State Department—at least at the time. His interest lay in creating the most expansive list possible; a feat easily accomplished with an outdated chart and no real government oversight.

|

Figure 11. Survey path of the Wilkes Expedition. Tokelau’s four islands were visited in 1841, as indicated by white flags. Three islands were reported inhabited, while no landing was possible at Olohega. The crew named the island Swains, and observed it to be “well wooded with cocoa-nuts.” (Courtesy of the David Rumsey Map Collection, annotated by the author) |

Strategic Possibilities

Government involvement in the affairs of “guano islands” waned in the years before and after the U.S. Civil War; it was an introspective time. Far-away islands held little relevance. By the late-1860s, the guano trade was in decline due to the discovery of extensive beds of mineral phosphates in South Carolina, Florida, and Tennessee.54 After World War I, the discovery of the chemical means to make fertilizer (and explosives) also contributed to the decreased demand for guano.55 In addition, many of the islands originally claimed, mined, and abandoned by Americans had been taken over by the British, in the name of the Crown, with some islands leased for copra operations rather than guano extraction.56

It was at the crossroads of Anglo counterclaims and new strategic possibilities in the early 1930s that the State Department finally launched an exhaustive evaluation of all the islands, rocks, and keys bonded under the U.S. Guano Act. Its findings are recorded in an almost 1,000-page typed document divided into three volumes. The third volume deals exclusively with claims in the Pacific, and it is here the State Department scrutinizes most closely as to whether each guano island claimed by Taylor meets statutory muster.57 The preparators’ real purpose for working through 75 years-worth of scattered, disorganized records was to ascertain the “sovereignty” of each island in anticipation of their other uses.58 A map published by the American Geographical Society in 1932, titled Possessions and Territorial Claims of the United States, is a visual investigation along similar, if not identical, lines as the memo.59

Figure 12. Detail of 1932 map. Placenames underlined in red are “U.S. Possessions or Territories,”

and those marked with a “G” in parentheses indicates U.S. guano islands.

Twenty of Taylor’s 21 existent islands are shown above.

(Courtesy of the David Rumsey Map Collection)

While the State Department memo from the early 1930s is of great benefit as a catalog of claims and bureaucratic processes (or lack thereof), the title indicates a wade into uncharted waters: “The Sovereignty of Guano Islands.” Use of the word “sovereignty” in conjunction with these islands is legally and semantically fraught, in large measure because the Guano Act specifies a unique territorial status of guano claims: “appertaining.” According to legal scholar Christina Duffy Burnett:

Early drafts [of the guano bill] contained references to the United States’ ‘sovereignty,’ ‘territory,’ and ‘territorial domain,’ but these words would disappear from the final version. The word ‘appertaining,’ however, survived.60

Questions related to what it means for an island to “appertain” to the United States extend into the present: If “appertain” signifies a temporary arrangement, what are the legal means (if any) by which an “appurtenance” becomes a permanent U.S. possession or territory?61 The legal advisors who put together the 1930s memo, state their work led them to believe “that no one knew what the Guano Act really did mean,” and recognized the problematic wording regarding the status of these islands. “The use of the use of the word ‘appertain’ is deft,” the advisors wrote, “since it carries no exact meaning and lends itself readily to circumstances and the wishes of those using it.”62

“The term’s lack of significance was, of course, its great advantage,” asserts Burnett, and with the passage of time, guano islands appertaining to the U.S. would take on “great strategic value through their location with respect to trade routes… sites of lighthouses, meteorological stations, and radio stations; or later (most importantly in the Pacific and especially during World War II), as landing strips.”63 In the late 20th century, U.S. guano islands became valuable for their surrounding maritime entitlements made possible by an international law called the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. In 1981, a year before the law’s adoption, lawyer Geoffrey Dabb observed: “We have now entered the era of the 200-mile zone, and the map of the Pacific will not be the same again.”64

Modern House of Tokelau

In May 2000, a delegation from Tokelau attended the Pacific Regional Seminar of the United Nations Decolonization Committee. Aliki Faipule Kolouei O’Brien gave a strong and clear speech on the “Modern House of Tokelau.” In his closing remarks, he said:

We do not see ourselves as a colony. We see ourselves as Tokelau, a unique people trying to survive…We want to survive economically and we want Swains Island back.65

At the close of the 20th century, it could be argued, Swains (Olohega) had already been lost and the forum to petition for its return no longer includes the U.N. The reasons are complex, but the crux of the problem is the U.S. and its desire to retain Olohega as a territory in order to maximize American Sāmoa’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). New Zealand—Tokelau’s administering power under the U.N. decolonization scheme—helped the U.S. achieve that aim by negotiating a delimitation treaty favorable to American Sāmoa, though harmful to Tokelau. As a result, the loss of Olohega is a wound that will not heal, and there is little chance forward in efforts to “decolonize” Tokelau (or other like schemes) without addressing the absence of the fourth island.66

Figure 13. Map of the United States EEZ (areas shown in dark blue).

An EEZ is a 200-nm zone that extends seaward from the baseline of a coast or island.

Eight of the islands named above were first claimed as U.S. guano islands.

Three of the eight were included in Taylor’s fraudulent claim:

Palmyra Atoll, Kingman Reef, and Olohega. (NOAA, annotated by the author)

Olohega and several other “guano islands” retained by the U.S. are the (overlooked) loci of an expanded territorial domain in the Pacific; an expansion made possible by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, or UNCLOS.67 The law, which took almost a decade to craft (1973-1982), provides coastal and island nations a legal framework for claiming maritime zones. Wealthier nations, like the U.S., use these zones as protected marine sanctuaries, or no-go zones, where commercial fishing is either off-limits or tightly restricted.68 For less-affluent island nations and territories, like Tokelau, the most important zone for generating a Western-style economy is the 200-nautical-mile EEZ. The EEZ makes it possible to negotiate lucrative commercial fishing licenses for access to its waters. Licenses generate income while simultaneously ensuring fish stocks aren’t depleted by overfishing.69

UNCLOS is beneficial on many fronts provided delimitation treaties between neighboring island nations are negotiated equitably and in good faith.70 Unfortunately, this was not the case when a delimitation (marine boundary) treaty was negotiated between Tokelau and American Sāmoa in advance of establishing their respective EEZs.71 The U.S.—the administering power for American Sāmoa under the decolonization scheme—used the treaty as an opportunity to push for recognition of “U.S. sovereignty over Olohega,” and made clear to New Zealand “that a maritime boundary treaty could be negotiated only if the Olohega claim was explicitly renounced (not merely left dormant).”72 According to Huntsman and Kalolo in The Future of Tokelau:

When EEZs were being declared in in the 1970s, the United States undertook to clear up its dubious Guano Acts claims, which had been made to virtually all the atolls in the Central Pacific, by making treaties with the nation-states involved. In the case of Tokelau, this meant New Zealand. The United States’ position was that it would give up its claims under the Guano Act to the three atolls if Tokelau/New Zealand would never press any claim to Olohega/Swains.73

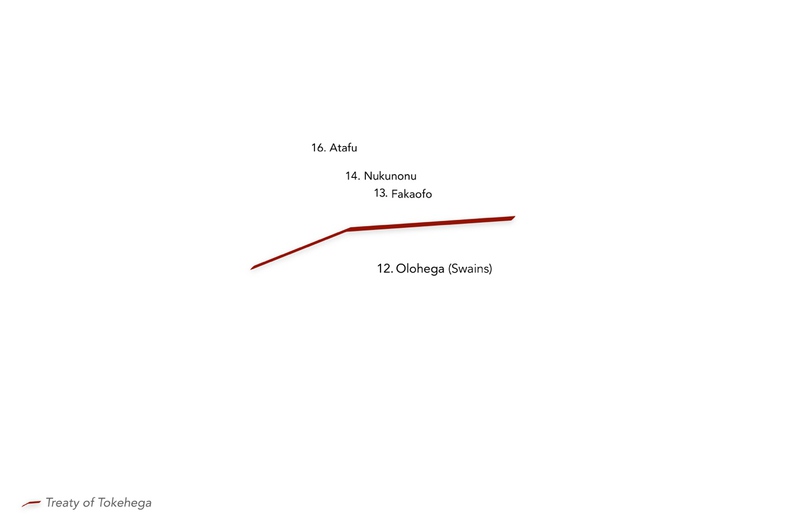

United States: Treaty of Tokehega

To fully understand this maneuver, and how Taylor’s fraudulent claim expressed itself in 20th-century treaty negotiations, it’s necessary to retrace the main points of this paper. First, the renunciation of the claim to three of Tokelau’s islands at the expense of its fourth, Olohega, is a false bargain. The islands the U.S. was willing to “give up” never met the government’s own legal criteria as “guano islands” under the Guano Islands Act of 1856. The three atolls—Atafu, Nukunonu, and Fakaofo—were inhabited at the time Taylor submitted his affidavit of discovery in 1859; a fact that had been established 18 years prior by the U.S.-sponsored Wilkes Expedition.

In the late 1970s when the delimitation treaty was being negotiated, the only possible “evidence” to support U.S. ownership of all four of Tokelau’s islands is derived from their inclusion in the official list of bonded claims.74 The legitimacy of the official list, however, is undermined by the fact that Taylor’s claim accounts for 60 percent of islands ever bonded under the act. The claim, then as now, is fraudulent, as evidenced in the incontrovertible fact that 22 of his 43 islands do not exist (though they can be found in the Norie chart of 1836, the source of Taylor’s information). Despite the claim’s numerous statutory deficiencies, none of Taylor’s 43 islands were ever removed from the official list by the State Department. It bears repeating that inclusion in the official list of “Guano Islands Appertaining to the United States” has only ever meant the claimant has the right to mine guano on a particular island, not the right to possess the island in perpetuity.75

Despite the numerous deficiencies, Tokelauans were dissuaded from pursuing their sovereignty claim in the late 1970s; there was pressure to have the delimitation treaty signed as quickly as possible. The pressure came from New Zealand, the “colonial power” tasked under the U.N. decolonization scheme to assist Tokelau toward self-determination and independence.

New Zealand: Treaty of Tokehega

In 1980, the delimitation treaty, referred to as the Treaty of Tokehega, was signed according to what the U.S. had asked for: Olohega, with a guarantee there would be no challenge to the island’s sovereignty in the future.76 New Zealand, Tokelau’s administering power, favored the treaty for multiple reasons, though the overt reason given to Tokelau’s leaders was that without the treaty, the southern boundary of their EEZ would remain unresolved; and without resolution, the sale of licensing fees for access to those waters would be limited.77 Those fees, New Zealand argued, would help move Tokelau “towards running its own affairs and to a greater economic self-sufficiency.” Tokelauans were also told by legal advisors in the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs their claim to Olohega would not hold up in a tribunal.78

With the signing of the U.S.-New Zealand delimitation treaty, the question of Olohega was pre-emptively settled outside the realm of ongoing decolonization efforts.79 Tokelau, New Zealand’s “last colony,” has been in the U.N.’s list of non-self-governing territories since 1946. It is unclear if Tokelau will ever be “delisted,” or why it is relevant at this point, because no one seems to hear the Tokelauan perspective on why Olohega matters. In Aliki Faipule Kolouei O’Brien’s speech to the U.N. Decolonization Committee, presented two decades after the signing of the Treaty of Tokehega, he offered this lucid explanation:

We have retained our claim to Swains Island within our oral culture, in songs and dance, passed down by our forefathers. We have cited external documents that support this claim. This is an issue of great pain to Tokelau. It is also an issue that could lighten the pressures and the need for fertile land to grow food and for the production of copra….We want to survive economically and we want Swains Island back.80

Concluding Thoughts: ‘Settling the Status’

The U.S. formally relinquished its “claim to sovereignty over the islands of Atafu, Nukunonu, Fakaofo” with the signing of the Treaty of Tokehega. In return, New Zealand agreed to abandoned any claim to Olohega. While this trade-off is not explicitly stated, it is obliquely indicated in a clause pertaining to American Sāmoa. As Ambassador William Bodde explained to Congress in 1981:

In the case of the Tokelau claim to Swains Island, this was taken care of by agreeing to place Swains Island on the United States side of the boundary and was reinforced by a clause noting that New Zealand has never claimed or administered any island in American Samoa as part of Tokelau.81

The Congressional record lays bare the economic motivations behind the treaty and other so-called “friendship treaties” with Pacific island nations negotiated around the same time: “The four treaties…provide for settling the status of 25 small islands to which the United States has claims, for establishing maritime boundaries for American Samoa, and for facilitating access to fishing grounds for boats serving the canneries in American Samoa.”82

By placing Olohega (Swains) on the U.S. side of the maritime boundary, American Sāmoa increased its EEZ. Conversely, Tokelau’s potential for an increased EEZ diminished, perhaps irrevocably. That’s because the EEZ is measured outward from the shoreline of each island within a territory. If Olohega were placed on the Tokelau side of the maritime boundary, it would mean the baseline for establishing its 200-nautical-mile EEZ would be anchored to Olohega’s shoreline rather than Fakaofo’s.83

Figure 14. The red line approximates the maritime boundary established by the U.S.-New Zealand treaty.

It stands as a dividing line between Olohega and the three other islands of the Tokelau group.

(Graphic by the author)

Fifteen of the “25 small islands” renounced by the four treaties originate with Taylor’s affidavit of discovery, the basis of U.S. sovereignty claims (Table 2).84 The remaining existent islands in Taylor’s affidavit are accounted for in the following way: one was annexed to a U.S. Territory (Olohega); two were annexed as U.S. Possessions (Kingman Reef and Palmyra Atoll); and three have yet to be formally relinquished by the U.S. government (Ongalewu, Makin, and Marakei).85

For some Pacific Islanders, the time for “settling the status” of these islands arrived a little too late and in the wrong forum. Taylor’s fraud—a theft of real and nonexistent “islands in a far sea,” taken from an outdated chart, placed on paper, and perpetuated through official lists—is the foundation of a legal legacy that must end. For it to end, we must first understand the initial fraud and why it persists in other forms at the continued detriment of island nations.86

Table 2. Disposition of 18 islands in Taylor’s affidavit of discovery.

Their inclusion in his list of islands is the basis of contemporary U.S. sovereignty claims.

Bibliography

Addison, David. J. and John Kalolo. Tokelau Science Education and Research Program: Atafu Fieldwork August 2008/Polokalame Akoakoga Faka Haienihi I Tokelau: Galuega FakaTino i Atafu 2008. Pago Pago: Samoan Studies Institute and the Tokelau Department of Education, 2009.

Allen, Percy S. Stewart’s Handbook of the Pacific Islands: A Reliable Guide to All the Uninhabited Islands of the Pacific Ocean: For Traders, Tourists And Settlers. Sydney: McCarron, Stewart & Co., 1920.

Behm, E. “Das Amerikanische Polynesien und die politischen Verhältnisse in den übrigen Theilen des Grossen Oceans im J. 1859 (Nebst Karten, Taf. 8 u. 9).” Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen 5 (1859): 173-194.

Bertram, I. G. and R. F. Watters. “New Zealand and its Small Island Neighbours: A Review of New Zealand Policy toward the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau, Kiribati and Tuvalu.” Wellington: Institute of Policy Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, 1984. Available online from the Victoria University of Wellington.

Burnett, C. D. “The Edges of Empire and the Limits of Sovereignty: American Guano Islands.” American Quarterly 57, no. 3 (2005): 779-803.

Dabb, Geoffrey. “The Law of the Sea in the South Pacific.” In Pacific Island Year Book. Edited by John Carter. Sydney: Pacific Publications, 1981.

Findlay, A. G. A Directory for the Navigation of the Pacific Ocean with Descriptions of its Coasts, Islands, etc. 2 vols. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013. First published 1851 by R. H. Laurie.

Fisher, Susanna. The Makers of the Blueback Charts: A History of Imray Laurie Norie & Wilson Ltd. Cambridgeshire, UK: Imray Laurie Norie & Wilson, 2001.

Hague, J. D. “On Phosphatic Guano Islands of the Pacific Ocean,” American Journal of Science and Arts 34 (1862): 224-43.

Haskell, Daniel C. The United States Exploring Expedition, 1838-1842 and its Publications 1844-1874. Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publishing, 2002. First published 1842 by the New York Public Library.

Hauʻofa, Epeli. “Our Sea of Islands.” The Contemporary Pacific 6, no. 1 (Spring 1994): 147-161.

Huntsman, Judith, and Kelihiano Kalolo. The Future of Tokelau: Decolonising Agendas, 1975-2006. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2007.

Huntsman, Judith, and Antony Hooper. “Who Really Discovery Fakaofo…?” The Journal of the Polynesian Society 95, no. 4 (1986): 461-467.

Ickes, Betty. “Expanding the Tokelau Archipelago: Tokelau’s Decolonization and Olohega’s Penu Tafea in the Hawaiʻi Diaspora.” PhD diss., University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 2009. ProQuest (UMI3378303).

Matagi Tokelau: History and Traditions of Tokelau. Translated by Judith Huntsman and Antony Hooper. Apia and Suva: Office of Tokelau Affairs and Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the Pacific, 1991.

Nichols, Roy F. Advance Agents of American Destiny. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1980. First published 1956 by University of Pennsylvania Press.

O’Brien, Aliki Faipule Kolouei. “The Modern House of Tokelau.” Pacific News Bulletin 15, no. 6 (2000): 4-5.

Orent, Beatrice, and Pauline Reinsch. “Sovereignty over Islands in the Pacific.” The American Journal of International Law 35, no. 3 (1941): 443-461.

Roosevelt, Franklin D., and J. S. Reeves. “Agreement over Canton and Enderbury Islands.” The American Journal of International Law 33, no. 3 (1939): 521-526.

Skaggs, Jimmy M. The Great Guano Rush: Entrepreneurs and American Overseas Expansion. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1995.

Soons, A. H. A. Addendum to ‘Climate Change: Options and Duties under International Law,’ The Hague: T.M.C. Asser Press, 2018. Available online from the Royal Netherlands Society of International Law.

Stanton, William. The Great United States Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975.

Starbuck, Alexander. History of the American Whale Fishery from its Earliest Inception to the Year 1876. Washington, 1878.

U.S. State Department. A Digest of International Law. Edited by J. B. Moore. 8 vols. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1906.

———. “Letters Sent Regarding Bonds of the Guano Companies, 1856-1912.” Vol. 7 in Records of the Department of State Relating to Guano Islands, 1852-1912. Washington, DC: National Archives Microfilm Publication M-974 [CD-ROM], 1975.

———. “The Sovereignty of Guano Islands Claimed under the Guano Act.” Edited by E. S. Rogers and Frederic A. Fisher. 3 vols. Washington, DC: Legal Advisor’s Office, Department of State, 1932. Available online from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library.

Winthrop, Colonel W. “Our Lesser Insular Appurtenances.” The Independent 51, no. 2641 (July 1899): 1877-1879.

Wilkes, Charles. Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition during the Years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. 5 vols. Philadelphia: C. Sherman, 1844.

Maps

Bartholomew, J. G. South Pacific Ocean on Mercators Projection….[map]. 1:25,000,000. In: J. G. Bartholomew. Times Survey Atlas of the World. London: The Times, 1922, Plate 102.

Norie, J. W. (Composite of) A New Chart of the Pacific Ocean, Exhibiting…All the Numerous Islands and Known Dangers Situated in Polynesia and Australasia….[map]. 1:9,650,000. In: W. Norie. London: J. W. Norie & Co., 1836.

———. The Marine Atlas, or Seaman’s Complete Pilot for all the Principal Places in the Known World….[map]. Scales differ. In: J. W. Norie. 7th ed. London: J. W. Norie & Co., 1826.

Paullin, C. O. and J. K. Wright. Possessions and Territorial Claims….of the United States, also Certain Military Operations and Grounds Formerly Frequented (ca. 1815-1860) by American Whalers….[map]. Scale not given. In: Charles O. Paullin and John K. Wright. Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1932, Plate 166.

U.S. Exploring Expedition (1838-1842). Groups in the Western Part of the Pacific Ocean Examined and Surveyed by the U.S. Ex. Ex. [map]. 1:14,800,000. In: Charles Wilkes. Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition During the Years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard, 1845, v. 5 front.

Appendix

Approach

The information presented in this annotated document represents William W. Taylor’s relationship to a chart as opposed to the actual Pacific Ocean; with calculations based on a paper map, or plane, rather than a spherical Earth. In straightforward terms that means the latitude and longitude of Taylor’s islands were weighed against measurements taken from the Norie chart of 1836, with no consideration of bearing. In column C, any differences in the coordinates between the two sources are noted in degrees, minutes, and inches. Also, no distinction is made between existent and nonexistent islands until the final analysis since almost all exist in a pictorial sense in the Norie chart.

To provide context for any differences between the two sources, it is important to consider actual physical distance on the chart apart from conceptual meaning. While 1° at sea is equal to 69 miles of latitude or 54.6 miles longitude, on the Norie chart it is a physical distance of ∼ 0.31 in., with one minute of latitude or longitude approximate to the width of a human hair.

Final Analysis

Taylor listed the island names and coordinates of 43 islands in his affidavit of discovery. Forty of those islands can be found in the Norie chart. When the coordinates of the two sources are compared, the positions of 24 of the 40 islands appear as an exact match. Ten are an approximate match, with a difference of 7′-40′ in either lat. or long.; four islands vary by 1° or more in either lat. or long.; and two islands were placed by Taylor on the wrong side of the Greenwich meridian, though the degrees and minutes correspond to islands by the same name in the Norie chart.

If a standard deviation of 4′-9′ (±0.03 in. sd.) is applied, the number of exact matches increases to 30 islands. And finally, the percentage of coordinates found to be exact between the two sources is higher among nonexistent islands (62.5%) than islands that exist (37.5%).

Sources

The document is the second handwritten list of Taylor’s islands from the archives of the U.S. State Department. The list is included in the deed to his assignee, the U.S. Guano Co., notarized February 12, 1859.

Measurements were derived from a scale reproduction of the Norie chart, (Composite of) A New Chart of the Pacific Ocean…by J. W. Norie & Co., published in 1836. The chart is available online from the David Rumsey Map Collection.

Content/graphic by the author.

Notes

The author of this paper refers to Tokelau as a “nation,” which may be interpreted as incorrect. Its usage is a conscious circumvention of the many terms (and abbreviations) used to describe low-lying island groups with distinct indigenous populations based on U.N. nomenclature and Western metrics. It is used similarly to how the term is employed by North American indigenous peoples (e.g., Navajo Nation).

The inclusion of all four islands in Tokelau’s 2006 draft constitution proved controversial; as a result, Olohega was relocated to the preamble as a “historic” reference. Huntsman and Kalolo, The Future of Tokelau, 232-233. See also CIA World Factbook, s.vv. “Disputes – international,” “American Samoa.”

Eight of the nine “United States Minor Outlying Islands” were first claimed as “guano islands.” See ISO 3166.

Olohega is located in a region of high rainfall (250-500 cm per year), which precludes guano deposits. As documented in oral tradition and in situ archaeology, Tokelauans claimed/made use of the island prior to Western occupation. See Matagi Tokelau.

Taylor assigned his claim to one of Alfred G. Benson’s companies, an enterprise derogatorily referred to as “Benson’s Monstrous Guano Empire.” Roy F. Nichols, Advance Agents, 233.

Ibid., 199: “It was suspected that these guano promoters and their sea-captain friends had taken old charts and listed as many islands as they could imagine were possessed of guano.” Skaggs’ reference is verbatim from a State Dept. memo, “Sovereignty of Guano Islands,” 3:873.

In 1859 Atty. Gen. Jeremiah Black issued strong opinions on the “conditions of annexation,” which ruled out making claims by cartography alone. If the State Dept. had implemented “Black’s Rules,” Taylor’s claim would not have been certified. See 9 Ops. 364, 367, 406 (1859) in Digest of International Law, 1:558-561.

Olohega’s private owners as well as the press perpetuate the misconception that “Swains Island first became a territory of the United States on Aug. 13 [sic], 1856 under the Guano Act.” Fili Sagapolutele, “Jump-Starting Swains’ Economy,” Samoa News, Dec. 9, 2017. For further elaboration, see n. 61.

See Michael Field, “Tokelauans Told Their Claim on U.S. Territory of Swains Island Is Weak,” Pacific Islands Report, July 4, 2002; legal expert Chris Beeby later changed his position and favored a re-examination of the claim, possibly through an international court of law. Bertram and Watters, “New Zealand and its Small Island Neighbours,” 233-236.

Removal of guano from these islands is a theft to the local ecosystem. Recent research suggests seabird guano run-off provides fertilizer for coral reefs, with the potential to “boost the reefs’ fish stocks by up to 48 percent.” Lina Zeldovich, “Banking on Bird Shit,” Hakai Magazine, Feb. 9, 2021.

See Nichols’ strong views on the alliance between sea captains and guano merchants, Advance Agents, 196-200. The total number of claims is derived from a handwritten record of all bonded claims on file with the U.S. Treasury Dept., dated Jan. 21, 1899. U.S. State Dept., “Letters Sent Regarding Bonds,” 7:0212-0214.

Clarifying statement from the Sec. of State T. F. Bayard to the México Minister to the U.S. Matías Romero. Feb. 18, 1886. U.S. State Dept., Digest of International Law, 1:559-560.

Olohega falls into two disqualifying categories: inhabited and located in a region of high rainfall. For clarity, it’s only counted once in the first category.

One rare reference to certificates issued for Taylor’s “guano islands” appears in The Internal Revenue Record & Customs Journal 6, no. 13 (1867): 113-114, a preprint of a Treasury Dept. “Circular Relative to the Guano Islands,” dated Aug. 23, 1867. Over time, proof that the bond requirement of the act had been fulfilled (Sec. 1415) became the more important document of the two. For details on the bond, see n. 44.

“What were once, if shown at all, indistinguishable from fly-specks upon the map may emerge as of vast importance in permitting man to move quickly from one hemisphere to another.” Roosevelt and Reeves, “Agreement over Canton and Enderbury Islands,” 521; see Hauʻofa for definition of ocean peoples, “Our Sea of Islands,” 152-153; biologist Mark Rauzon says “several families of seabirds exhibit extreme natal philopatry, and any habitat loss sets back the breeding population…it can take two decades for colonizing birds to find and breed in a new colony (email comm. 2021).”

To date, no other reference to “Low Islands” has been found, though Taylor’s coordinates leave no doubt he meant Fakaofo. In 1859 the island would have been known as Bowditch (Wilkes Expedition, 1841). The inhabited island was “discovered” by “at least six captains of four nationalities between 1835 and mid-century.” See Huntsman and Hooper, “Who Really Discovered Fakaofo…?,” 461-467.

William W. Taylor, Deed to G.W. Benson, U.S. State Dept., “Letters,” 7:0147-0150. Alfred Benson aggressively sought to corner the guano market in the Pacific through two companies: American Guano Co. and the U.S. Guano Co. He maintained a long-term grievance with the government over the “Los Lobos” affair. See Skaggs, Great Guano Rush, 21-32.

William W. Taylor, Affidavit of Discovery, U.S. State Dept., “Letters,” 7:0142-0145. The news clip is an announcement of France’s claim to Clipperton Island, published in the New-York Daily Tribune, Feb. 12, 1859.

New-York Daily Tribune, March 8, 1859. (Many sources have incorrectly cited the publication date as March 5.)

U.S. Guano Co. Bond, U.S. State Dept., “Letters,” 7:0103-0106. A claimant is required to “enter into bond,” which is not money upfront but a penalty if provisions of the act haven’t been met (Sec. 1415).

Taylor’s mastery at sea is questionable. His only recorded “South Seas” voyage lasted five months and upon return, the brig Grand Turk was “condemned.” His last voyage ended with the bark Gov. Hopkins “lost on the coast of Brazil.” Starbuck, History of the American Whale Fishery, 364-365, 484-485.

E. Behm, “Das Amerikanische Polynesien,” 173-194; The Nautical Magazine, “Nautical Notices,” 500-501.

The $100,000 bond covered all of Taylor’s islands and three more claimed by other whaling captains (Washington, Starbuck, and Gardner Is.); collectively the 46 islands are referred to as the Number 9 group.

Without doubt, Wilkes’ five-volume Narrative would have been available to the State Dept. In 1844, Congress designated the Sec. of State to act as distributor of the voyage’s complete works. See Haskell, The United States Exploring Expedition, 151-155.

The accounts of Padel (1848) and Murray (1868) have been brought to the fore by scholars working in the 21th century. See Ickes, “Expanding the Tokelau Archipelago,” 54-56, 167-168, 178-180.

See Table 2 for the disposition of 18 of Taylor’s existent islands. Three islands were retained by the U.S.

The list from 1894 is reproduced in the government-affiliated Digest of International Law, 1:566-568; for more on the “caretaker of claims” and the chronology of lists, see Skaggs, Great Guano Rush, 121-123.

In the case of Arenas, Mexico first contested the claim in 1882. The Sec. of State finally had it “struck from the list” in 1894, but only after Mexico had “filed various historical proofs of the title of Spain and of the rights of Mexico as her successor.” U.S. State Dept., Digest of International Law, 1:570-571.

U.S. State Dept., “Sovereignty of Guano Islands,” 3:630. This document was made publicly available in its entirety in 2016, thanks to the efforts of Gwen Sinclair and the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library.

“Acts of possession have occasionally been performed by persons without any previous official authorization. Generally, these uncommissioned acts have been either ignored or repudiated by Great Britain and the United States.” Orent and Reinsch, “Sovereignty over Islands in the Pacific,” 450.

The heading of Bowler’s list reads: “List of guano islands, appertaining to the United States, bonded under the act of Aug. 18, 1856, as appears from bonds on file in the office of the First Comptroller of the Treasury, Sept. 16, 1893.” Cf. to language in H. Res., n. 39.

Taylor’s assignee entered into bond on Feb. 8, 1860. According to Sec. 1415 of the act, “a breach of the provisions” within a specified time meant “forfeiture of all rights accruing under and by virtue of this chapter.” The bond for Taylor’s islands specified a two-year timeframe; none were ever mined and no guano was ever delivered to American citizens. It’s up for debate when exactly the bond was null and void. See U.S. Guano Co. Bond, U.S. State Dept., “Letters,” 7:0103-0106.

There is only section in the act that provides for transferable rights in the event a discoverer dies before “perfecting proof.” Even then, what is being transferred to a widow, heir, or administrator is not title to an island but the exclusive rights to mine its guano deposits upon satisfactory completion of the requirements in Sec. 1412. See R.S. Sec. 5572 (1872).

The Treasury Dept. arranged its lists by bond number, then alphabetized the island names within each bond group (Taylor’s claim is included in bond group No. 9). Taylor’s original arrangement of islands can be ascertained from his affidavit of discovery (Fig. 5) and the list included in the deed to the U.S. Guano Co. (Appx. 1). U.S. State Dept., “Letters,” 7:0141-0142, 7:0148-0149.

Nassau, Low, and Samarang appear in Taylor’s list but not in the Norie chart (Samarang is the same as Palmyra). In 1836, Low had just been “discovered” by an American whaler and would not been listed in the charts that year. See De Wolf’s Island in the New-Bedford Gazette & Courier, Nov. 30, 1835. The same applies to Nassau, also “discovered” by an American whaler in 1835. See Findlay, Directory for the Navigation of the Pacific Ocean, 2:898.

Geographer E. Behm corrected Taylor’s positions for Baumans, Enderburys, Sydneys, Makin, and Mathews in his 1859 article, “Das Amerikanische Polynesien.” Behm’s corrections correspond to the exact position of the islands in the Norie chart of 1836.

Cf. Norie’s 1836 chart to his 1825 chart of the Pacific in The Marine Atlas. The London-based cartographer made reputable maps popular among American whalers, but in the late 1830s there were signs he was “tiring” at the end of a prolific career, with the “quality of his enormous output…falling.” Fisher, Makers of the Blueback Charts, 95.

Detailed charts of all four of Tokelau’s islands in the Atlas of the Narrative of the U.S. Ex. Ex., vol. 2., can be viewed here and here.

Findlay, Directory for the Navigation of the Pacific Ocean, 1:xx-xxi. The charts produced by the Ex. Ex. were considered the finest of their time, though the State Dept. seemed to have little use for them. Almost a hundred years later, the U.S. military utilized them during World War II. See Stanton, Great United States Exploring Expedition, 365-366.

Redundancies in Taylor’s list of islands are not fabrications, as many have speculated. As one example, Flints and Flint are both in the Norie chart but only one is real. To add to the confusion, Flints exists but is presently called Flint, without the “s.”

Prior to the launch of the Ex. Ex., Jeremiah Reynolds created a “list of islands” for Congress by crowdsourcing data from whaling captains, navigators, and “ships’ logs and journals kept between 1805 and 1820.” His compilation was an invaluable resource for the expedition, and perhaps set a precedent for the notion whalers were good (albeit imprecise) sources of island information. See Stanton, Great United States Exploring Expedition, 16, 18, 234.

For a brief political history of natural and manufactured fertilizer, see Anthony S. Travis, “Dirty Business,” Chemical Heritage (Spring 2013): 7.

British citizens weren’t allowed to take possession of islands in pursuit of private interests like their American counterparts. “Under the aegis of the empire” crown permits were awarded to companies to mine or operate copra plantations on select isles. See Skaggs, Great Guano Rush, 224-225. The best statistical information (though anthropologically flawed) on the status of island claims and much else for this time period is the Australian publication, Stewart’s Handbook of the Pacific Islands.

The preparators display a range of opinions, though they tend to give Taylor the benefit of the doubt: they opine he probably invented islands, intentionally altered coordinates for known islands, listed two separate islands when there is only one with two names, etc. See U.S. State Dept., “Sovereignty of Guano Islands,” vol. 3.

“Other uses” includes trans-Pacific aviation, communication systems, and military installations. See Polk, “American Polynesia.”

Former “guano islands” retained by the U.S. are referred to in the U.S.C. as “possessions,” not territories. Olohega is a special case; its status changed from “appertaining to the United States” to becoming a territory of American Sāmoa via annexation in 1925. In short, its status as a guano island does not make it a U.S. territory.

Dabb, “Law of the Sea in the South Pacific,” 21. See the ISA for current benefits of the 200-nm zone.

NZ Administrator to Tokelau, Ross Ardern, said he’s “not detected any overt ambition to include Swains Island in any current discussions” he’s had with the Tokelau government in the last three years (email comm. 2021). Sources with close ties to the Tokelau community say it remains a topic of concern, with the feeling they were “ill-done-by” and that “Tokelau is not whole without Olohega.”

The U.S. has yet to ratify UNCLOS, though it is one of its main beneficiaries with the second largest EEZ in the world. According to former Defense Sec. Leon Panetta, “We are the only permanent member of the U.N. Security Council that is not a party to it.” See Austin Wright, “Law of the Sea Treaty Sinks in Senate,” Politico, July 16, 2012.

NOAA National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa is made up of six management areas, which includes the “Swains Island Unit.” Visitors aren’t allowed to go ashore without prior permission from the private owners. See recent developments with Palau here.

The main threat to the depletion of fish stocks is the unlicensed activities of distant-water fishing fleets in hard-to-patrol areas within and adjacent to EEZs. See Michael Field, “Why the World’s Most Fertile Fishing Ground Is Facing a ‘Unique and Dire’ Threat,” The Guardian, June 13, 2021. To learn about traditional Tokelauan fishing techniques, see Chap. 17, Matagi Tokelau.

UNCLOS may not be an ideal equalizer because the “major colonial powers, notably the United States, Great Britain, France and Japan, receive huge bonanzas in terms of 200-nm exclusive economic rights that flow from their colonial legacies, while China comes up short.” See Gavin McCormack, “Troubled Seas.”

The role of treaties in establishing EEZs is discussed in Soons, Addendum to ‘Climate Change,’ 99.

Bertram and Watters, “New Zealand,” 234. For more on the U.S. as an administering power, see Fili Sagapolutele, “American Samoa Political Status an ‘Internal’ Matter,” Pacific Islands Report, Nov. 8, 2006.

Cf. bargaining with Tokelau to attitudes toward the U.S. treaty with the Cook Islands: “[C]laims to these particular islands arise…by execution of guano bonds under the Guano Islands Act of 1856. The U.S. claim has virtually no legal merit and is not supported by any other nation….The islands are inhabited.” Comm. on Foreign Relations, Treaty with the Cook Islands on Friendship and Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary, S. Rep. No. 98-7, at 2 (1983).

Nor does the act provides the means to transfer a guano island to the U.S. government. As has been publicly stated by numerous officials during treaty discussions in the U.S. Senate: “The principle [sic] basis for our claims were activities undertaken pursuant to the Guano Act of 1856. It is clear that this Act was never intended to serve as a basis for the extension of U.S. sovereignty over islands from which Guano was taken….What the treaties surrender are substantiated claims, not territory of the United States.” Comm. on Foreign Relations, Treaty of Friendship with Tuvalu, S. Rep. No. 98-5, at 21 (1983). It’s questionable whether Taylor’s claim has ever been “substantiated.”

The name of the treaty, “Tokehega,” is a combination of TOKElau and OloHEGA. For other meanings of the hybrid word, see Huntsman and Kalolo, Future of Tokelau, n. 8, 271.

Tokelau was led to believe the treaty would result in revenue from American fishing fleets; there’s no evidence the current success with its fisheries is attributable to the U.S. See Fatu Tauafiafi, “Tokelau’s Tuna Success—Testament to Pacific Solidarity’s Multimillion Dollar Effect,” FFA’s TunaPacific, Dec. 18, 2016.

According to historian Betty Ickes, the treaty “was meant to deny a future self-governing ‘sovereign’ Tokelau the possibility of reclaiming Olohega—an option which Tokelau continues to occasionally assert when the opportunity arises.” Ickes, “Expanding the Tokelau Archipelago,” 75.

Pacific Island Treaties: Hearings on Friendship Treaties with the Republic of Kiribati, Tuvalu, Cook Islands, and Tokelau, Before the Comm. on Foreign Relations, 97th Cong. 1 (1981) (statement of William Bodde Jr., U.S. Ambassador to Fiji, Kingdom of Tonga, Tuvalu and Minister to the Republic of Kiribati). While it’s technically true New Zealand never administered Olohega as part of Tokelau, the U.K. did, or attempted to do so, and considered the island group part of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony prior to 1925. See Stewart’s Handbook, 231, 556.

Ibid. (statement of Daniel A. O’Donohue, Deputy Assistant Secretary for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, Department of State). Other objectives include the mining of seabed minerals, use of islands for military purposes, and the protection of U.S. interests in the Pacific due to the changing status of colonial dependence.

For specifics on territorial loss as a result of the treaty, see Betty Ickes, “Letter to the Editor,” Pacific Islands Report, July 21, 2002. For more on how EEZs are measured and why it matters, see Soons, Addendum to ʻClimate Change.’

Between 1979 and 1980, the U.S. relinquished sovereignty claims to 15 islands claimed by Taylor through three separate treaties: Cook Islands (TIAS 10774), New Zealand/Tokelau (TIAS 10775), and Kiribati (TIAS 10777).

Ongalewu (Nassau) is located in the northern Cook Islands. Makin (Pitts) and Marakei (Mathews) are neighboring islands located in the Republic of Kiribati.

Cf. “islands in a far sea” to “a sea of islands” in Hauʻofa, Our Sea, 152-155. To learn about Tokelauan resiliency, culture, and natural resource management, see Addison and Kalolo, Tokelau Science Program/Polokalame Akoakoga Faka Haienihi I Tokelau, 1-74.