In the two years since 2010, the Asia-Pacific region has been roiled by rival territorial claims and counterclaims to islands, islets, and rocks scattered across the East China Sea, Yellow Sea, the Japan Sea and the South China Sea. In 2012 alone, strong claims and counter-claims to insular territories have been made by Japan, China, and Taiwan (Senkakus/Diaoyu), Japan and South Korea (Dokdo/Takeshima), and China, the Philippines and Vietnam among others (South China Sea islets). These official claims, moreover, in many cases have been reinforced by nationalist statements and actions by citizens and groups, and by clashes on the high seas contesting territorial claims. In evoking military alliances, Japan has brought the US into the picture in relation to its claims to the Senkakus, while the US has positioned itself to intervene in the South China Seas clashes, setting up intensified US-China conflict. In a major examination of the Senkaku controversy, Gavan McCormack locates the issues within the broader terrain of the 1982 UNCLOS transformation of the Law of the Seas which has transformed a world of open seas into one in which the major colonial powers, notably the United States, Great Britain, France and Japan, receive huge bonanzas in terms of 200 nautical mile exclusive economic rights that flow from their colonial legacies, while China comes up short. The result is to raise fundamental questions about the premises of the UNCLOS order. Asia-Pacific Journal coordinator.

Part One – The Pacific

Dividing Up the Oceans

“Modern” history has been the history of states and empires and the lands they controlled and exploited, with the sea (save for a narrow coastal strip) the site of battles for its control but never the property of any state. That is no longer the case. Under the 1982 UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea) Third Convention, much of the “high” seas was divided up and allocated to nation states in the form of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) over which states enjoyed special rights akin to resources ownership to a distance of 200 nautical miles (370 kilometres) beyond their 22 kilometre (12 mile) territorial waters, and even further, to a limit of 350 nautical miles (650 kilometres) in the event of the outer reaches of the continental shelf being shown to extend so far. It was a decision that drastically shrank the global “high seas” and privileged countries that had the good fortune to possess substantial sea frontage or far-flung islands, including especially former imperial powers, notably France and the United Kingdom, which emerged with their advantages confirmed and reinforced by their possession of far-flung islands left behind by the waves of decolonization.

The 1982 agreement was almost a decade in the making (1973-1982), took another decade before coming into force, in 1994, was ratified by Japan in 1996, and by 2011 had been adopted by 162 countries. It aimed to set international standards and principles for protection of the marine wildlife and environment and provide a forum for resolution of disputes over boundaries and resource ownership. It gave coastal nations jurisdiction over approximately 38 million square nautical miles of ocean, which are “estimated to contain about 87 per cent of all of the known and estimated hydrocarbon reserves as well as almost all offshore mineral resources” and almost 99 per cent of the world’s fisheries.1 The United States, though participating in the various conferences since 1982 and claiming the largest exclusive economic zone in the world, covering 11,351,000square kilometres in three oceans, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean Sea, is one of the few that has not ratified the agreement, evidently in keeping with the reluctance to compromise US exceptionalism by submitting to the authority of any international law.2

In maritime terms, one effect of the law has been to strengthen Japan’s entitlements as a major global power. Its various extensive ocean territories entitle it to a vast ocean domain across the North and Northwest Pacific, with as yet largely unknown economic riches but increasingly evident strategic significance. The contrast in these terms with China is striking. China’s coastline, though at 30,017 kilometres nominally slightly longer than Japan’s 29,020 kilometres,3 carries only relatively small ocean entitlement and, for major sections, it abuts the EEZ’s of neighbour states including Japan and South Korea. Its only direct Pacific frontage is via Taiwan. Japan, by contrast, enjoys an EEZ of 4.5 million square kilometres (world No. 9) so that its maritime power is more than five times greater than China, which with 879,666 square kilometres ranks No. 31, between Maldives and Somalia.4 Convulsed at the time by imperialist assaults and domestic turmoil, China played no part in the 19th and 20th century processes of dividing up the Pacific land territories and plays none now in dividing up its ocean.

In that context, Japan’s present and prospective island territories, till 1982 little more than remote navigational points, assume large significance. This essay considers two maritime zones, first those in the Pacific and Philippine Sea which in the main constitute part of the Metropolis of Tokyo, and second the East China Sea zone surrounding the islands known in Japan as Senkaku, and in China and Taiwan as Diaoyudao and Diaoyutai respectively (both abbreviated in the following to Diaoyu).

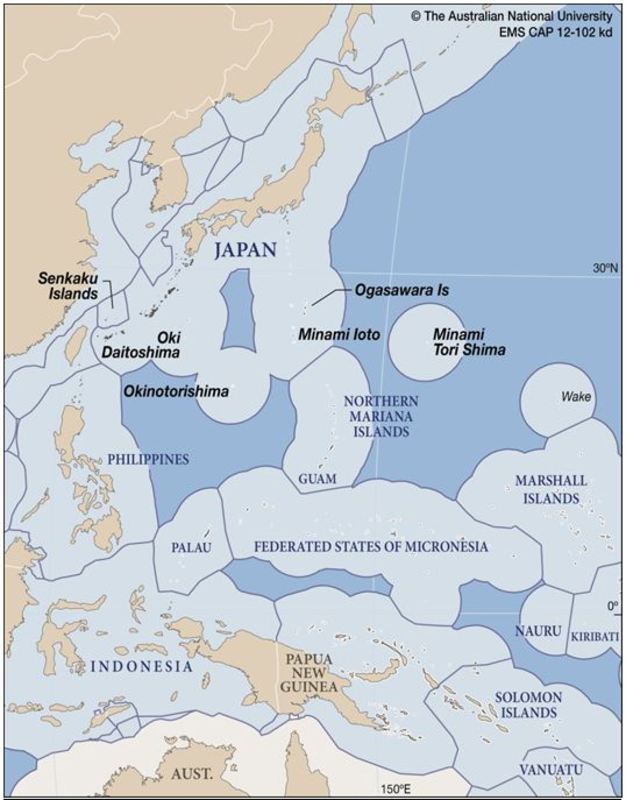

The following map shows the pattern of maritime appropriation across the Western pacific and well illustrates the importance of the EEZs, the shrinkage of “open” sea,” and (from a Chinese viewpoint) the growing threat of potential blockage of access to the Pacific as hostile or potentially hostile forces spread their EEZ wings over so much of it. Commonly denounced for its claims to islands, reefs and shoals in the South China Sea, when viewed in global terms China is a minor player in its claims on world oceans, although that fact might reinforce its determination not to yield in the spaces where it has a claim.

Tokyo – Island City

|

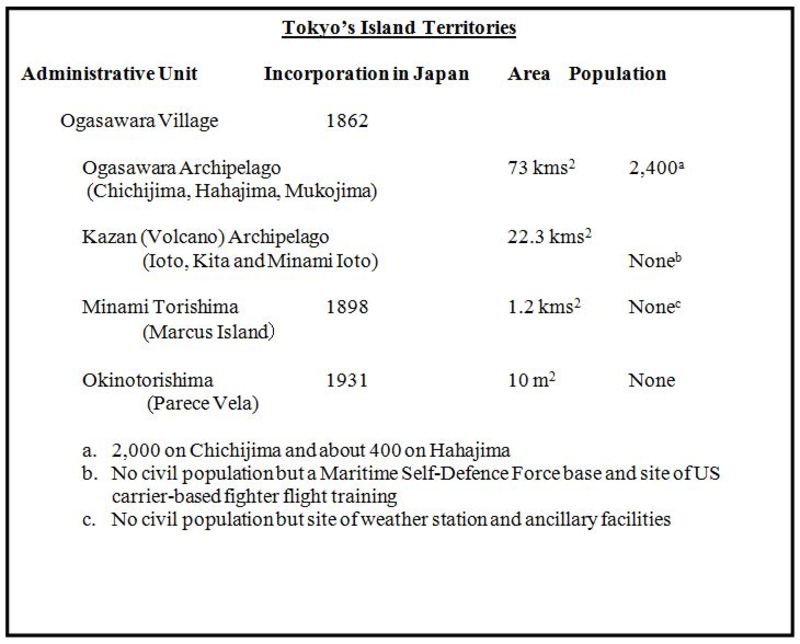

Tokyo is unquestionably one of the world’s largest metropolises, Japan’s national capital as well as its economic and cultural powerhouse and home to more than 13 million people. It is also an island city whose domain extends over great swathes of the Pacific. Its jurisdiction extends to a maximum of almost 2,000 kilometres into the Pacific, including first seven volcanic islands known as the Izu Islands that sprinkle the ocean beyond the Izu peninsula, the Ogasawara island group beyond that and approximately 1,000 kilometres from Tokyo, and two small but hugely important rocky outcrops: Okinotorishima, 1,740 kilometres south-west from Tokyo and Minami Torishima, 1,848 kilometres from Tokyo. The former is Japan’s most southerly and the latter its most easterly territory. In April 2012, Governor Ishihara Shintaro proposed extending that domain by approximately 1,900 kilometres to the southwest to include the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands (transferring them from nominally private ownership to his Metropolis).

Apart from the Izu islands, whose links with pre-modern Japan were strong, Japan’s claim to the others is relatively recent. Ogasawara village, which is administratively part of Tokyo City, extends far across the seas. The islands (sometimes also known as the Bonin Islands), were first formally claimed by Japan and a Japanese flag was raised over them in 1862. Ogasawara “village” includes its core component, the Ogasawara archipelago, together with the Volcano Island group and several tiny outcrops. The Ogasawara Archipelago itself comprises three sub-groups known as Chichijima (Father) Hahajima (Mother) and Mukojima (Bridegroom) Archipelagos and currently accessible only by the weekly steamer service from Tokyo to Chichijima that takes about 26 hours. The communities on Chichijima and Hahajima number around 2,400 people.5 148 kilometres to the southwest of this extended family island group lies the Kazan (Volcano) Island archipelago, comprising also three small islands, the central one, Ioto (formerly Iwojima, site of fierce fighting in 1945) being 1,200 kilometres from Tokyo, just 21 square kilometres in area, and home only to a small Self-Defence Force base, while to its north and south, across a 137 kilometres stretch of ocean, lie North and South (Kita and Minami) Ioto, neither of them populated and with a combined area of approximately seven square kilometres.6 The Kazan Island group also includes a small rather barren active caldera, Nishinoshima, with elevation of 38 metres and area about 22 hectares but growing since 1973 because of the ongoing eruption. A further six hundred kilometres to the southeast of this Volcano group lie the American territories of the Mariana Islands.

Within the Ogasawara Village administrative unit are included also two tiny territories whose value was suddenly and enormously enhanced by the UN decision: Minami Torishima and Okunotorishima. Minami Torishima, 1,848 kilometres southeast of Tokyo, also sometimes known as Marcus Island, is an outcrop with a surface area of 1.2 square kilometres. Annexed by Japan in 1898, today it hosts only a weather station and small airport, with no civilian population.7 Okinotorishima consists just of two outcrops of coral reef in the Philippine Sea with a total area of about 10 square meters, shrinking at high tide so that one is about the size of a double bed and the other a small room, at an elevation of around 7.4 centimetres above the sea surface. The Japanese claim to it, based on the terra nullius principle, i.e., as being unclaimed by any other state, was first advanced in 1931. Once the implications of the UN decision were understood, from 1987 Tokyo City began investing heavily in the building of “steel breakwaters and concrete walls” designed to shore the reef up and prevent it disappearing.8 After investigations commissioned in 2004 and 2005 by the Nippon (formerly Sasakawa) Foundation, Ishihara’s Tokyo adopted plans for the construction of a lighthouse and building of port infrastructure, a power generation plant, housing, etc.9 A very considerable sum, estimated at $600 million, has been outlayed on concrete and titanium to date as part of Tokyo’s mission to retain Okinotorshima and a surrounding EEZ.10

These widely scattered archipelagos and reefs known collectively as “Ogasawara” were occupied by the United States in 1945 and returned to Japan in 1968. In the interim, they were used, inter alia, for stockpiling nuclear weapons. In 2011 UNESCO recognized the ecological significance of the Ogasawara islands by designating them a World Heritage site.

While Ogasawara Village and its various outlying island territories constitute, administratively, part of Tokyo Metropolis, as the EEZ map above illustrates there is also one additional island group, not part of Tokyo, that carries significant EEZ entitlement and deserves mention here. The Daito (Daitoshima) group, about 350 kilometres east of Okinawa’s main island, comprises the three islands of North Daito, South Daito and Daito (12.7. 30.5, and 1.1 square kilometres respectively, with populations of 700, 1,400 and 0). Administratively, they form part of Okinawa prefecture and though tiny, with their surrounding EEZ they too carry entitlements to a large area of ocean. Daito Island itself is unoccupied because it has been a US Navy firing range since 1956 and it is assumed that little life survives on it.11

Islands? Rocks?

The question, under UNCLOS, is whether all such territories qualify, strictly speaking, as islands, which carry the EEZ entitlement. An “island,” according to Article 121 of the Convention, is a “naturally framed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide.” The law spells out that “rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no economic zone or continental shelf.” Under such provisions, there seems no reason to doubt the claims on behalf of the Ogasarawa and Kazan archipelagos, or the Daito islands. Some doubt might be raised as to Minami Torishima on the point of whether it could really “sustain human habitation or economic life,” but so far as Okinotorishima is concerned, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the claims by Japan, and the Tokyo Metropolis, stretch the law to the breaking point. Okinotorishima has never sustained any kind of economic life and is only kept above sea level by dint of considerable effort and expense. Yet both the Government of Japan and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government insist otherwise and base large ocean claims upon that proposition.12 A Foreign Ministry spokesperson in 2005 explained: “The island [Okinotorishima], under the Tokyo Municipal Government, has been known as an island under Japanese jurisdiction since 1931, long before the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea came into existence. Having ratified the Convention in 1996, Japan registered its domestic laws concerning its territorial waters, in which Okinotorishima is included as an island, to the Secretary-General of the UN in 1997. … Article 121 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea defines that ‘an island is a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide.’ This is exactly what Okinotorishima is.”13

The disproportion between the scale of the “island” and the breadth of sea entitlement attaching to it is extreme. The basic area of sea on a radius of 370 kilometres (200 nautical miles) around any fixed point recognized as an “island” is 428,675 square kilometres. If that was then extended to the theoretical maximum under the continental shelf extension rule to 350 nautical miles or 650 kilometres, the EEZ entitlement would become a staggering 1,337,322 square kilometres, three and a half times the land area of Japan (378,000 square kilometres). The circular sectors on the map of Western Pacific EEZs above illustrate the extent of ocean EEZ claims based on tiny outcrops that may or may not qualify as “islands.” With seabed riches only beginning to be understood, and in the event that its interpretation of the law is upheld, the 1982 UNCLOS treaty constitutes for Japan a huge bonanza.

The question of interpretation of the UN law is of course crucial. It appears that in respect of competing claims by China, the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia to tiny islands in the South China Sea, however, parties other than China have explicitly ruled out territorial or continental shelf claims, adopting the view that the capacity to sustain habitation and economic activity is a strict requirement for recognition as an “island” for UNCLOS purposes.14 Should that view prevail, at least some of Japan’s Pacific claims would fail, as would some of China’s in the South China Sea.

Japan’s Ambit Claim of 2008

In November 2008, Japan made a submission to the UN Committee on the Continental Shelf, seeking to further increase its territory by the addition of 7 “blocks” of ocean, making up a total of 740,000 square kilometres. That is to say it sought to extend its 200 nautical mile (370 kilometres) boundary to 350 nautical miles (650 kilometres). The claims were presumptive in the sense that they took for granted the entitlement to the basic 370 kilometre zone.

By far the largest block was that known as the Southern Kyushu-Palau Ridge, anchored on the Okinotorishima reef (approximately 257,000 square kilometres). Neither China nor South Korea contest Japan’s claims over the rocks as such, but both insist that a rock is a rock, not an island, and therefore cannot carry any entitlement to an EEZ.15 Both submitted Notes Verbales to the Committee making this point.16 Implicit in their objection is the position that rocks carry no entitlement to any EEZ, not just to the claimed extension.

Three and a half years later, in April 2012, the UN’s Committee on the Limits of the Continental Shelf issued its interim decision. The Japanese media reported a victory for Japan’s diplomacy and the granting of the reef-based claim.17 The Asahi gloated, saying “This is a good opportunity for China and South Korea to recognize the facts.”18

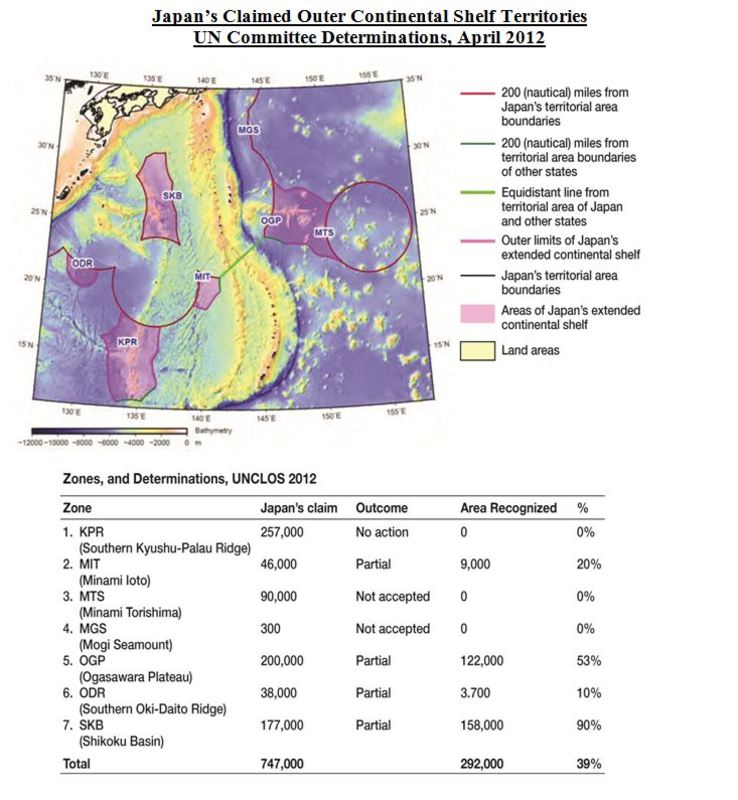

The following map, which is the one used by the government of Japan to present its claims to the UN Commission in 2008, shows the claims and the outcome in 2012 from the UNCLOS determination.

Source: Map taken from Japan’s submission to Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, “Summary of Recommendations of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in Regard to the Submission made by Japan on 12 November 2008,” adopted with amendments, 19 April 2012. (accessed 12 July 2012). Details of area (in square kilometres) and percentages taken from the State Oceanic Administration of China, “Guojia haiyangju pilu Riben wai dalu jiahuajie’an zhenxiang,” Dongfang zaobao, 10 July 2012, http://www.dfdaily.com/html/51/2012/7/10/822204.shtml (English translation at “Japan’s outer continental shelf delimitation of truth: the multi-block area not approved,”), Dongfang zaobao, 10 July 2012 (Accessed 22 July 2012). |

Significant parts of the Japanese overall claim were indeed accepted, in relation to more than half (and in one case 90 per cent) of two of its seven claims, in Zones 2, 5, 6, and 7, for a total area of about 290,000 square kilometres (39 per cent of what it had claimed). However, in zones 1, 3, and 4, including the Southern Kyushu-Palau Ridge (KPR) (Okinotorishima), Motegi Plateau (MGS) and Minami Torishima (MTS), the claims were either set aside without determination or else rejected.

In the words of the Commission’s chair, addressing the KPR (Okinotorishima) claim,

“The proposal did not receive a two-thirds majority: out of 16 members, five were in favour, 8 were against and 3 abstained. The Commission’s considered that it would not be in a position to take action on the parts of the recommendations relating to the Southern Kyushu-Palau Ridge region until such time as the matters referred to in the communications referred to above [i.e., the Chinese and South Korean Notes Verbales] have been resolved.”19

That is to say, until and unless the Committee decides otherwise, it would not discuss the proposal further. For the Japanese claim to a vast stretch of strategically crucial ocean to rest on a tiny, uninhabited and uninhabitable rock seems at least to be stretching the intent of the law. At some point there will presumably have to be either an agreement or a judicial determination of such claims. Despite the triumphalist tone of Japanese coverage of the outcome of its submission on a matter to which it attached great importance it was defeated in a vote of 15:8:3.

Though parts of Japan’s claim may well not proceed, or may be struck down by some form of international arbitration, the developments of the UNCLOS regime to date have favoured it in terms of legitimizing its control, even virtual ownership, of large stretches of ocean. In other words, irrespective of its claims on problematic “island” territories or extended continental shelf zones, its gains over undisputed maritime territory based on ownership of scattered small islands are still large. The economic importance of the sea area that surrounds Japan’s various island domains is only slowly coming to be appreciated. One recent estimate valued Japan’s potential seabed resources at a staggering $3.6 trillion.20 Just months after the UNCLOS determination, a team of University of Tokyo researchers announced, following a long voyage of Pacific resource exploration, that it had found a large deposit of rare earth deposits, “estimated to be more than 220 times Japan’s annual consumption of about 30,000 tons,” near Minami Torishima. Most, though not all, it reported, were within Japan’s claimed EEZ, even though one site lies 500 kilometres to its north and in this zone UNCLOS rejected Japan’s extended shelf claim in 2012.21

The combination of Japan’s “ownership” of large tracts of ocean with its subservience to US strategic and military design signifies serious potential Chinese disadvantage and risk. Japan’s Okinotorishima lies between China’s first and second island chains. As Tokyo Governor Ishihara noted, “Okinotorishima stands between Guam – America’s strategic base – the Taiwan strait, China, and areas near Japan where there may be conflict in the future…”22 Whatever the eventual determination of the extended continental shelf claim based on Okinotorishima, Tokyo plans to construct there by 2016 an artificial island with harbour infrastructure including heliport and radar facilities, while promoting the exploitation of the resources of the surrounding seas.23 As for Minami Torishima, it lies beyond even the second of those putative Chinese lines.

The uncompromising Japanese insistence on national interest, however narrowly construed and even to the point of readiness to manipulate international law (Article 121 of the UN Law of the Sea) to advance it, can hardly be conducive to a peaceful, long-term Pacific order.

Given the large Japanese gains under the 1982 UNCLOS regime, from which China gains relatively little, and given the steady deepening and reinforcing of the walls of containment being constructed by Japan in conjunction with the United States to attempt to constrain China, whether in East Asia (reinforcing the US military presence in Okinawa, extending the Japanese military presence from Okinawa Island through into its South Western islands, for the first time, and advancing the principle of “inter-operability” by which Japanese and US forces constitute a single military unit, united in intelligence, command, and potentially in mobilization) or in Southeast Asia (where the US is increasingly active in attempting to block China’s territorial claims), the Chinese claim to Senkaku//Diaoyu, whose islands lie well within 200 nautical miles of its coast and on the edge of its continental shelf, assumes exceptional importance.24

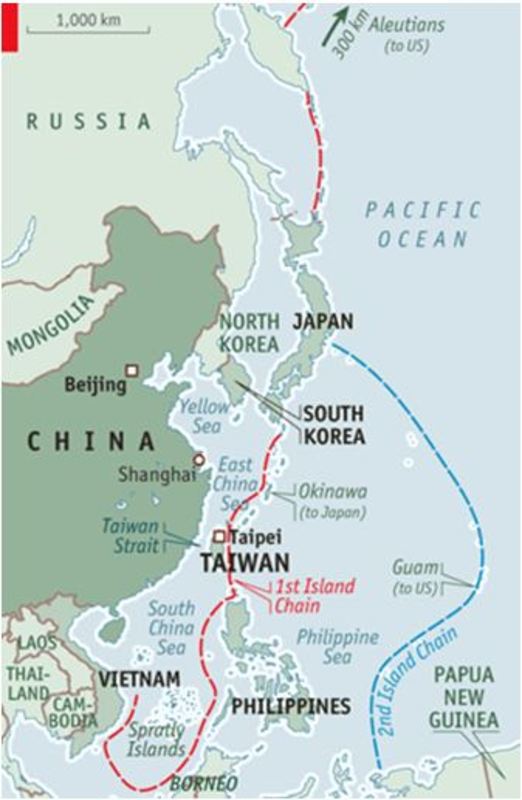

The US, which has announced its intention to concentrate 60 per cent of its navy – six aircraft carriers plus “a majority of our cruisers, destroyers, littoral combat ships and submarines” in the Pacific, i.e., primarily with China in its sights, by 2020,25 currently outspends China by a huge margin (approximately 4.7 per cent of its much larger GDP as against 2 per cent in the case of China),26 and its own strength is complemented by significant naval expansion on the part of the three US allies, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea. US defence planners insist they are responding to the threat posed by the Chinese build-up, although China has yet to launch a single aircraft carrier.27 They call the Chinese strategy one of “A2/AD” (Anti-Access/Area Denial). China, they say, has drawn First and Second Island Defence Lines,28 and is concentrating on developing the capacity in the event of hostilities to deny hostile access within the seas bound by the first line, drawn from the Korean peninsula, through Jeju island, the Okinawan islands, Taiwan, and the Philippines (the Yellow, East, and East China Seas, China’s “near seas”), while building also significant capacity within the seas bounded by the second line, through Ogasawara, the Marianas, Palau to Indonesia, and eventually (by 2050 or thereabouts) extending naval operational capacity to the “far seas;” i.e., becoming by then something like the US, at least in the Northwest Pacific.29

The emerging pattern in this sector of the Northwest Pacific as a consequence of UNCLOS is for the advantages enjoyed by the United States and its allies to be greatly enhanced, with China not figuring at all in the picture. If China is indeed pursuing a goal of “break out” from within its first line of naval defence, as a Pacific and then global naval power, as many commentators suggest, UNCLOS has made its task harder.

|

|

Intent on maintaining strategic and tactical superiority over China and defying its “A2/AD” aspirations in advance, the US in 2010 developed what it refers to as its “Air-Sea Battle” concept, followed early in 2011 by the “Pacific Tilt” doctrine. The commitment under the former to coordinated military actions across air, land, sea, space, and cyber space to maintain global hegemony and crush any challenge to it, and the shift under the latter of the US’s global focus from the Middle East and Africa to East Asia have profound implications for Okinawa. From the Chinese viewpoint the Okinawan islands resemble nothing so much as a giant maritime Great Wall intervening between its coast and the Pacific Ocean, potentially blocking naval access to the Pacific Ocean. For Okinawa it means that those islands become nothing less than a “front line.” Parts of the island chain, including notably the Miyako and Yaeyama (Yonaguni, Iriomote, and Ishigaki) island groups might be seen as fronting, if not straddling, the First Chinese line, while the Miyako strait (between Okinawa Island and Miyako Island), offers a crucial access path for Chinese naval forces to and from the Pacific, through waters which Japan concedes are international (or “open seas”) but within Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Okinawans note grimly that the implications of the two doctrines – dispersal of US forces to locations at or beyond the “second line” (Guam, Tinian, the Philippines, Hawaii, and northern Australia) where vulnerability to Chinese missile or naval attack might be minimized – are that the front-line role assigned to Okinawa is assumed to carry a high degree of vulnerability.

Part Two: The East China Sea

The Ishihara Bombshell

In April 2012, Tokyo Governor Ishihara Shintaro announced to a conservative American think-tank audience in Washington, D.C. that his city was negotiating, and had reached agreement in principle with the private owners, to buy the three privately owned islets of Uotsuri, Kita Kojima and Minami Kojima in the island group in the East China Sea just to the north of Taiwan known in Japan as Senkaku and in China and Taiwan as Diaoyu.30 Such purchase, he argued, was necessary to clarify public, governmental jurisdiction and remove any possible challenge to their sovereignty by China or Taiwan. From the time of his membership of the hawkish Dietmembers Seirankai (Blue Storm Society) in 1973, Ishihara had insisted on Japanese sovereignty and on the need to repel any Chinese challenge for control of these islands. He himself joined one rightist venture to the Islands in 1997 (though not setting foot on them).

The Senkaku/Diaoyu islands focus attention not only because of obvious and growing strategic and economic (fishing, oil) factors, but because they constitute the only sector of Japan’s frontier that is both contested and currently under actual Japanese control, unlike the so-called “Northern territories” that Russia controls and the island of Dokdo/Takeshima that South Korea controls. In administrative terms part of Ishigaki City and within the Yaeyama group, the five islands, more correctly islets, are known under their Japanese and Chinese names as Uotsuri/Diaoyudao, Kita Kojima/Bei Xiaodao, Minami Kojima/Nan Xiaodao, Kuba/Huangwei and Taisho/Chiwei. The largest of them (Uotsuri/Diaoyu; literally “Fish-catch” in Japanese, “Catch-fish” in Chinese) is 4.3 square kilometres and the total area of all five just 6.3 square kilometres. Though spread over a wide expanse of sea, they are located in relatively shallow waters at the edge of the Chinese continental shelf, 400 kilometres east of the China mainland coast, 145 kilometres northeast of Taiwan, and 200 kilometres north of Yonaguni (or Ishigaki) islands in the Okinawa group, separated from the Okinawan island chain by a deep (maximum 2,300 metres) underwater trench known as the “Okinawa Trough,” or in China as the “Sino-Ryukyu Trough. Four are privately owned, following their 1895 grant by Japan’s then Meiji government to the Fukuoka entrepreneur, Koga Tatsuichiro, and the other (Taisho/Chihwei), owned directly by the Japanese government. Koga’s business – initially albatross feathers and tortoise shells and later bonito processing – continued through his family till 1940. The owners (of four of the islands) and their descendants, therefore, effectively occupied them for about 60 years. Since then, however, though not setting foot on them for 70 years, they have continued to collect “rent” from the Government of Japan, currently running at an annual 25 million yen (ca. $310,000) for the first three listed above and an undisclosed sum for the fourth.31

The Sino-Japanese contest over these islands is complicated by the fact that sovereignty over them would carry Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) rights over a sector of the East China sea that is believed to be “the last remaining, richest, as yet unexploited depository of oil and natural gas …Oil reserves in the East China Sea are estimated by Western sources at 100 billion barrels.”32

Although the Japanese claim to the islands dates only to 1895, 16 years after incorporating the Ryukyu Islands as a prefecture (and extinguishing the Ryukyu kingship) and at the height of the Sino-Japanese War, nominally it rests not on any claim to “spoils of war” but on the terra nullius principle – that the islands were unclaimed by any other state when the Japanese claim was first made. Today, Japan points to the fact that China ignored Japan’s claim to these islets for 75 years after the initial Japanese cabinet resolution, until a 1968 ECAFE survey found that the area might be rich in hydrocarbon deposits. There is little dissent in Japan from the proposition that, in the words of former senior diplomat Togo Kazuhiko, Japan’s position is “fundamentally solid and quite tenable under existing international law.”33

However, there is a certain disingenuousness to this. The January 1895 cabinet decision, only taken after a ten-year delay and after defeating China in war, was then kept secret for 50 years (till the end of the China and Pacific wars), and it referred only to two of the five islands (Uotsuri/Diaoyu and Kuba/Huangwei).34 Furthermore, the islands were occupied militarily by the US from 1945 and China was not party to the post-war settlement at San Francisco in 1951 that placed them, together with the Ryukyu Islands, or Okinawa, under US trusteeship. For China, “normalcy” with Japan was not accomplished until 1972, also the year that the US returned administrative authority over Okinawa (including the Senkakus) to Japan. In other words, there was good reason why recourse to international law was not open to China – whether the Chinese Republic (whose capital moved from Nanjing to Taiwan in 1949) or the People’s Republic (from 1949) – until the time it was actually taken. As the anticipated withdrawal of US forces from Okinawa became imminent, attention naturally focussed on what was and what was not ”Okinawa” and to whom it should be “returned.”

Where Japan’s claim rests on a strict reading of international law (the terra nullius principle, unchallenged by China until 1970), China’s claim rests rather on longer history (and geography). Its close association with the islands in the context of China-Ryukyu diplomatic and trading relations under the East Asian “Tributary” trade system” (which had no place for Western notions of sovereignty) had been unchallenged through the half millennium prior to Japan’s “discovery” and China’s subsequent failure to challenge was indubitably linked to the long continuing military and diplomatic advantage Japan enjoyed. This key maritime border was only established in the context of Japan’s rise and China’s decline as the wave of high imperialism washed across East Asia.

Ishihara’s April 2012 proposal was a provocation and challenge to China. It served to reopen wounds in the bilateral relationship opened by the incident of September 2010. Then, the captain of a Chinese fishing boat that collided, twice, with a Japanese coastguard vessel in waters off these islands was arrested and subsequently released when the furore the event caused threatened to spin out of control. Events were only contained by what the New York Times described as Japan’s “humiliating retreat.”35 However, there was no letup in the protestations from Tokyo that there was “no room for doubt” and no dispute as to Japan’s ownership of the islands. Antagonism to China spread in Japan, feeding a national consensus that Japanese claims to Senkaku/Diaoyu were beyond question, that China was threatening Japan’s sovereign territory, and that its challenge called for reinforcement of Japan’s military presence in its Southwest islands and reaffirmation of the importance of the security alliance with the United States.

Having launched his 2012 bombshell, Ishihara accused China (because of its fishing boats entering the area) of being “halfway to a declaration of war,”36 and of being a “robber,” that was, he said, “’seeking hegemony in the Pacific, with the Senkaku/Diaoyu issue merely the first step of its ambition.”37 His plan was designed to ensure, that Japan’s claims would receive, firstly, the resolute backing of the Japanese state and Japanese public opinion, and secondly, full US security guarantee under the security Treaty of 1960.

His initiative was widely welcomed in Japan and its fierce and uncompromising language set the nation-wide tone. Chief Cabinet Secretary Fujimura Osamu indicated that the national government might be prepared to step in and buy the islands in place of Tokyo City, Ishigaki City’s town assembly declared its support for Ishihara’s plan,38 and Ishigaki’s mayor Nakayama called on Ishihara in Tokyo to deliver his support personally.39 An opinion survey found nationwide support for the proposal running at 61 per cent (54 per cent in Okinawa). Okinawan Governor Nakaima thought, somewhat improbably, that Tokyo’s purchase might help “stabilize” the situation around the islands,40 while Japan’s ambassador to China commented, more realistically, that implementation of the Ishihara plan would bring on a “huge crisis” in relations between Japan and China.41 (Ambassador Niwa Uichiro was promptly recalled to Tokyo, rebuked, and issued an apology.42 Late in August he was removed from his post.)

Summer Sailing

On the morning of 10 June, a flotilla of 14 vessels, with 120 people, including 6 Dietmembers, hosted by the National Council of “Hang-in There Japan!” (Ganbare Nihon), sailed from Ishigaki to the Senkaku vicinity under the banner of “Let’s fish at the Senkaku Islands!” 43 The following day, Ishihara testified before a committee of the Diet, with characteristic forthrightness berating the national government, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Diet for having “ignored the will of the people.”44 A little later, asked for a comment on the birth of a baby panda at Ueno Zoo, he suggested it be named “Senkaku” and sent back (sic) to China.45 His proposals, accompanied as they were by provocation and invective towards China, were then taken up in chorus by the national media and echoed by the Prime Minister.

The reverberations soon spread. On 4 July a boat dispatched by the Hong Kong-based “World Chinese Alliance in Defense of the Diaoyu Islands” sailed for the islands from Taiwan, escorted by 3 vessels of the Taiwan Coastguard. It displayed the Chinese (People’s Republic) five-star flag because, as they explained, leaving in a hurry, they had forgotten to bring the Taiwan (Republic of China) flag, along “with our seasick pills.”46 The name of their ship – “Happy Family” – in any case suggested that distinctions between states meant less to them than the fact of “Chinese-ness.”47

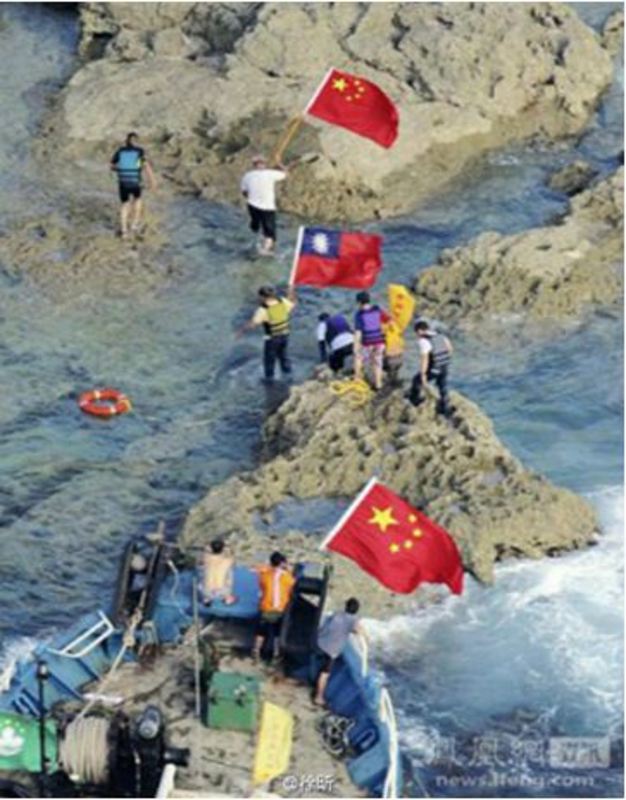

Three days later, Prime Minister Noda declared the islands Japan’s “koyu” (integral or inalienable) territory and that the national government would indeed buy and “nationalize” them, whether directly from the owners or indirectly should Tokyo purchase them first,48 and implement Tokyo’s plans for the construction of a port and a lighthouse.49 The Asahi trumpeted on 10 July that “China must rein in provocative acts around the Senkaku Islands,”50 though it was far from clear that Beijing would be able to rein in the World Alliance or, for that matter, the Taiwanese Coastguard. On 11 and 12 July, however, three fishing patrol vessels, this time actually from China (the People’s Republic) sailed through the area, provoking the recall of Japan’s ambassador from Beijing in protest. Yomiuri warned China that, “Infringement of Japan’s sovereignty cannot be overlooked.”51 On 15 August, the anniversary of Japan’s defeat in war in 1945 and therefore a day of large symbolic significance in East Asia, a Hong Kong vessel carried 14 “Defend Diaoyu” activists to the islands. Seven of them landed, this time carrying both PRC (China) and ROC (Taiwan) flags, before being detained, sent briefly by Japanese authorities to Okinawa, and then deported without trial.

Chinese party landing on Senkaku/Diaoyu, 15 August 201252 |

Days later, on 19 August, came the Japanese riposte: a convoy of 21 vessels (150 people) including national and local assembly politicians and Ganbaru Nippon’s head, Tamogami Toshio (former Chief-of-Staff of Japan’s Air Self-Defence Force and a noted right-wing revisionist and agitator) and members of the National Diet’s “Dietmembers acting to protect Japan’s territory”) sailed from the Okinawan island of Ishigaki, planted Japanese Hinomaru flags and conducted ceremonies to commemorate Japan’s war dead. They were given a pro forma official rap over the knuckles for having done so without authorization, accompanying a generally positive and congratulatory national reception.

|

|

By this time, passions ran high on all sides. Anti-Japanese disturbances broke out in Hong Kong and more than 20 cities across China – cars were overturned, Japanese restaurant windows smashed, and boycotts of Japanese goods threatened. Negative sentiments were reciprocated in Japan. An opinion poll conducted by the Japanese cabinet in November 2011, less than a year before this hot summer, found that 71.4 per cent of Japanese people reported having no feelings of “familiarity” or “warmth” (shitashimi) for China (against 26.3 per cent who had such feelings).53 One June 2012 survey found an overwhelming 84.3 per cent of people in Japan declaring their image of China to be “unfavourable.”54 In China a survey conducted by a Communist Party paper Huanjing shibao (though only through its website) found 90.8 per cent of readers agreeing to the proposition that China should discuss all means, including military, for addressing the Senkaku/Diaoyu problem.55 An editorial in China Daily referred to “distraught Japanese politicians” who “think only jingoism can restore Japan’s rightful place in the world.”56

No Dispute?

Although the Government of Japan kept reiterating its stance that the islets were “intrinsic Japanese territory” over which there was no dispute, in fact its position was disputed on all sides: by Washington (tacitly), and by Beijing and Taipei (publicly). Ever since it transferred administrative control over them to Japan in 1972, Washington has remained agnostic as to the rightful ownership of the islands, even on occasion referring to them by their Chinese name as if to drive home the point.57 The US position is especially paradoxical since, while on the one hand insisting it has no view on which country should own the islands, on the other it reiterates its security guarantee under the 1960 treaty, i.e., its readiness to go to war with China if necessary to enforce Japan’s claim. That stance was made abundantly clear by Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense Kurt Campbell as early as 1996,58 and has been reiterated from time to time since then, by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in October 2010,59 and by Campbell (then Assistant secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs) and other senior officials in August 2012.60

As for both the People’s Republic and the Republic of China, they plainly dispute Tokyo’s claims, the one referring to the Ishihara idea as “illegal and invalid” and the other as “unacceptable.”61 Taiwan (the Republic of China)’s president, Ma Ying-jeou, in 2012 restated his government’s position, insisting that the islands were “indisputably an inherent part of ROC territory, whether looked at from the perspective of history, geography, practical use or international law,” and proposed, albeit vaguely, to convert the region into a “sea of cooperation.”62 The China diaspora too seems united on this question, and the radicalism of the approach favoured by the World Alliance must trouble both Beijing and Taipei.

There is also a possible fourth party to the matter: the American family of descendants of the prominent late Qing official (Minister for Transportation), Sheng Xuanhuai, who by unconfirmed accounts was granted three of the islands by the then Empress Dowager, Cixi in 1893 (i.e. two years earlier than the Japanese cabinet decision granting them to the Koga family). According to that claim, Sheng was honoured by the empress for his herbal interests and production of blood pressure medicine derived from the islands’ leadwort or plumbago plants (“statice arbuscula” according to Lohmeyer, which is presumably an abbreviation for Plumbaginaceae Statice arbuscula Maxim).63 It is an intriguing, but unconfirmed, story, however, which the Sheng family evidently did not make public until around 1970 and appears subsequently to have decided not to press.64 Were it ever confirmed, it would have implications not only in respect of ownership but also to the Japanese claim that, as of 1895, the islands were terra nullius.

|

|

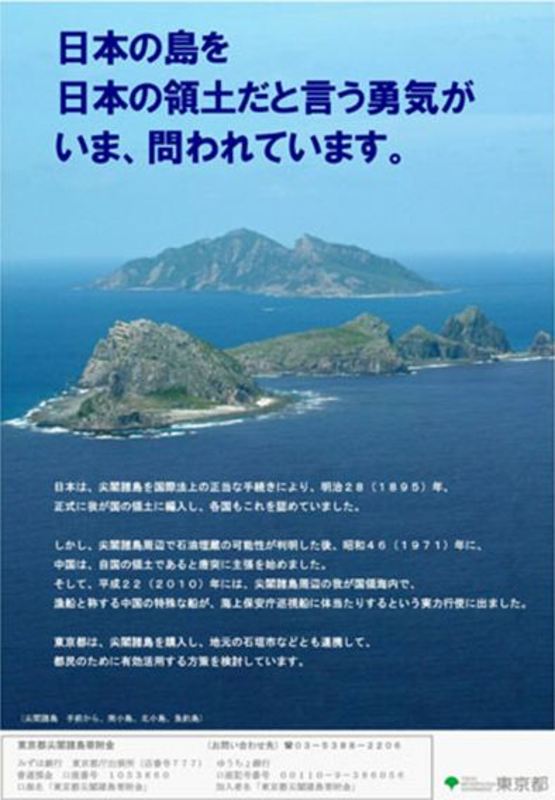

When serious doubts were raised over the legality of using public funds to carry out the purchase proposal, Ishihara on 27 April 2012 opened a private fund to collect public subscriptions. Money flowed in, 1.3 billion yen (about $16 million) by 5 July.65 Rightist and ultra-nationalist groups and their publications enthusiastically adopted the Senkaku cause.66 In July, Ishihara’s Tokyo Metropolitan Government published an advertisement in the Wall Street Journal (27 July) asking for US support for its island purchasing plan, and pointedly noting that the islands were “of indispensable geostrategic importance to US force projection.”67 Ishihara left no room for doubt as to the direction in which he proposed the United States project its force. At the same time his Metropolitan Government began distributing a poster featuring a photograph of the three islets that it was concerned with and the message calling for the “courage” to say that “Japan’s islands are Japan’s territory.”68 Late in August, the national government was reported to be close to a deal to purchase the islands for two billion yen (ca. $25 million).69

Despite the national government’s apparent submission in adopting his policy, Ishihara berated it for its “shoddy” behaviour and the (ruling) Democratic Party for being “in a chaotic situation.”70 Through the hot summer of 2012, Ishihara’s bold populist rhetoric was matched by a rising tone of righteousness and fury at China in the Japanese media. All reference to the islands came to be accompanied by one or other variant of the phrase “an integral part of Japan from the standpoint of both history and international law” or “historically and legally … an integral part of Japan territories.”71 With his government’s support levels falling, Noda stepped up the rhetoric by declaring in late July 2012 his readiness to deploy the Self-Defence Forces to defend the islands if necessary.72 However, Noda faced challenges on more than one front. Evidently anxious to cool the rising tensions with China, his government rejected Ishihara’s application to send a survey party to the islands, to which Ishihara wasted little time in declaring that he would go ahead anyway.73

The Problem of “Intrinsic” (Koyu) Territory

Both Ishihara and Noda, together with the entire Japanese national government and national media, shared the view that certain territories could possess some distinctive quality that makes them “koyu,” meaning intrinsic or inalienable, to a nation state and that Senkaku/Diaoyu was such a territory. Yet the word “koyu” (Chinese: “geyu”) is problematic. It has no precise English translation for the good reason that the concept is unknown in international law and foreign to discourse on national territory in much, if not most, of the world.74 Its use in Japan’s case also carries a peculiar irony since Japan’s claim to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands dates only to 1895 (its formal claim to Okinawa itself dates only to 1872). Furthermore, as Toyoshita Narahiko points out, two of the group of islands that Japan claims as “intrinsic” or “inalienable” are known, even to the Japanese Coastguard, by their Chinese names, Huangwei and Chiwei, rather than their Japanese names, Kuba and Taisho. Moreover, despite their supposed “reversion” (along with “Okinawa”) to Japan in 1972, both have remained under uncontested US control as a practice bombing range for well over half a century, with neither national nor metropolitan government in Japan ever seeking their return.75 Outspoken and bold when addressing China, the courage of Ishihara and other Japanese politicians and media figures appears to desert them when facing the United States, whether over Senkaku/Diaoyu or indeed even over Ishihara’s own domain in the Metropolis of Tokyo, where the little-used 700 hectare Yokota base sits on a prime site and the US Air Force maintains control over significant sections of the national capital’s air space.

The category of “koyu” or intrinsic territory also implies the possibility of territories that are less, non-intrinsic or peripheral, and the very shrillness of the Japanese insistence on Senkaku/Diaoyu being “koyu” serves to raise the suspicion that actually it is not. Such insistence might even be in inverse proportion to certainty over the legal and historical case, and be rooted, not in clarity and certainty, but in awareness that the Japanese entitlement is contested, uncertain, strongly opposed by both China and Taiwan and not even supported by Japan’s ally the United States. Shakespeare might have deemed this an instance in which the Japanese government “doth protest too much.”

Modern Japanese history points strongly to such a distinction. Japan’s main islands, Honshu, Kyushu and Shikoku, constitute the national core, parts of them especially intrinsic as “sacred” because of their close association with the imperial household. During the 19th century Hokkaido was added to constitute an extended “koyu hondo.” Resistance there had been crushed centuries earlier, and by the late 19th century it was populated overwhelmingly by settlers from core regions leaving the indigenous Ainu population marginalized. These four therefore constitute the lands that in English might be called “Japan proper, and are recognized from time to time within Japan as “koyu hondo,” literally the integral or inalienable mainland. Okinawa, however, remained in the penumbra between core and colony, resisting assimilation, and it continues to possess a distinct, peripheral character as “koyu no ryodo” (integral or inalienable territory).

Such “koyu no ryodo” are subordinate and may on occasion be used as negotiating ploys for the preservation of the interests of the “koyu hondo” core.76 The best example of this is that of the summer of 1945, when the Japanese state faced its greatest crisis, staring at defeat and possible collapse. A special mission to sue for peace, headed by Konoe Fumimaro (three times former Prime Minister) and commissioned by the emperor himself, was prepared for despatch to the Soviet Union. Though it was eventually abandoned as events moved quickly in June and July of 1945, its instructions were clear. Konoe’s principal goal was to ensure the “preservation of the national polity,” (i.e., the emperor-centred system) and to that end, so far as territory was concerned, it was assumed that the colonies would all be lost and in addition that Japan would have to be prepared to “be satisfied with “koyu hondo” which meant, if pressed, “abandoning Okinawa, Ogasawara and Karafuto (Sakhalin)” (while hoping to retain the Southern Kurile Islands).77 The Senkakus were too trivial even to mention, but plainly, as the periphery of the Okinawan periphery, they were on nobody’s mind.

Weak-kneed vs. Positive Diplomacy

The blessing given by the Showa emperor (Hirohito) to American military occupation of Okinawa, confirmed by the San Francisco Treaty and renewed in various forms by bilateral agreements even following nominal “reversion,” has meant that a level of Okinawan subordination to US military purposes that would be intolerable in “Japan proper” has been taken for granted as proper and enforced ever since. 78 “Koyu no ryodo” are inferior and dependent places that experience the discrimination of “koyu hondo.” Okinawa, having been successively claimed, sacrificed, reclaimed, and exploited by the Japanese nation state, is now proclaimed “integral” with special vehemence precisely because it is seen as secondary. Senkaku/Diaoyu, the periphery of the periphery, or the “integral territory” of other “integral territories” and therefore the feeblest unit in the nation state, is pronounced part of its essence, to be defended, if necessary, by the full force of the Japanese SDF and the US military under the Security Treaty.

The memory of the disastrous path onto which Japan was led over eight decades ago by insistence on “positive diplomacy” to defend the “lifeline” of inalienable territorial rights in “Man-Mo” (Manchuria-Mongolia), and ultimately China proper, has faded in Japan, but in China it is not forgotten. The uncompromising repetition of today’s no less strident but vacuous formula of koyu rights to Senkaku/Diaoyu is noted with foreboding. The fact that it is almost precisely echoed in territorial claims on all sides—by China (including Hong Kong and Taiwan), Japan and Korea, and by the South China Sea states in respect of that region’s maritime zones—makes it difficult to be optimistic of any easy or early resolution.

The unfolding of the events of 2012 showed just how easily public opinion can be inflamed. The self-righteous insistence on exclusive ownership, by any of the three state parties or, indeed, by the “World Chinese Alliance,” is unlikely to offer a way to convert the East China Sea into one of “Peace, Cooperation and Friendship.” As one looks in vain on all sides for some trace of the political wisdom and vision to declare such a program, it grows the more likely that, should it surface, it would be denounced as “weak-kneed.” While the Japanese (and international) media denounce China for its “increasingly narrow-minded, self-interested, truculent, hyper-nationalist” stance,79 and refer to China in the context of the ocean territorial disputes of 2012 as having “thrown down the gauntlet,” 80 in many quarters Tokyo’s uncompromising and belligerent tone passes without comment.

As events in the South China Sea are reported to be “moving in the wrong direction,” so that “the risk of escalation is high” with the possibility of tensions rising to “irreversible” levels,81 so too in the Pacific and East China Sea the stakes are high and the focus of high levels of national sentiment on contested territories, and the absence on all sides of a readiness to negotiate, bodes ill.

The author expresses his gratitude for advice and critical comment to Harry Scheiber of UC Berkeley Law School, Yann-huei Song of Academia Sinica, Taiwan, Paul D’Arcy of ANU, Unryu Suganuma of J.F. Oberlin University, and to Kay Dancy of ANU for cartographical assistance.

Gavan McCormack is an emeritus professor of the Australian National University and a coordinator of The Asia-Pacific Journal. His most recent book, co-authored with Satoko Oka Norimatsu, is Resistant Islands: Okinawa Confronts Japan and the United States, Rowman and Littlefield, July 2012 (Japanese, Korean, and Chinese translations to be published early in 2013.) He is the author of Client State: Japan in the American Embrace (New York, 2007, Tokyo, Seoul and Beijing 2008) and Target North Korea: Pushing North Korea to the Brink of Nuclear Catastrophe, 2004 (Seoul 2006).

Gavan McCormack, “Troubled Seas: Japan’s Pacific and East China Sea Domains (and Claims),” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 10, Issue 36, No. 4, September 3, 2012.

Articles on related subjects

•Carlyle A. Thayer, ASEAN’S Code of Conduct in the South China Sea: A Litmus Test for Community-Building?

•Wani Yukio, Barren Senkaku Nationalism and China-Japan Conflict

•Gavan McCormack, Mage – Japan’s Island Beyond the Reach of the Law

•Gavan McCormack, Small Islands – Big Problem: Senkaku/Diaoyu and the Weight of History and Geography in China-Japan Relations

•Wada Haruki, Resolving the China-Japan Conflict Over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands

•Peter Lee, High Stakes Gamble as Japan, China and the U.S. Spar in the East and South China Sea

•Tanaka Sakai, Rekindling China-Japan Conflict: The Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands Clash

• Koji Taira, The China-Japan Clash Over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands

1 Daniel J. Hollis (Lead Author); Tatjana Rosen (Contributing Author); Dawn Wright (Topic Editor) “United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), 1982,” in Encyclopedia of Earth. Eds. Cutler J. Cleveland (Washington, D.C.: Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment), first published June 22, 2010, last revised Date September 10, 2010; Retrieved June 14, 2012. <link>.

2 There is a strong case, however, for the advantages to be gained by the United States in joining UNCLOS. See Capt. (Ret.) Gail Harris, “U.S. must remove UNCLOS handcuffs,” The Diplomat, 23 March 2012. http://thediplomat.com/2012/03/23/u-s-must-remove-unclos-handcuffs/

3 According to the World Resources Institute. The CIA, using different criteria, shows China’s coastline to be much smaller, only 14,500 kilometres or less than half of Japan’s 29,751. (“List of Countries by Length of Coastline,” Wikipedia)

4 “Exclusive Economic Zone,” Wikipedia, accessed 9 August 2012. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exclusive_economic_zone#United_States/

5 On Ogasawara, see Nanyan Guo and Gavan McCormack, Ogasawara shoto – Ajia Taiheiyo kara mita kankyo bunka , Tokyo, Heibonsha, 2005, and in English “Coming to terms with nature: development dilemmas on the Ogasawara Islands,” Japan Forum, vol. 13, No. 2, 2001, pp. 177-193, and Nanyan Guo, “Environmental Culture and World Heritage in Pacific Japan: Saving the Ogasawara Islands,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 17-3-09, April 26, 2009 .

6 “Iwo jima,” Wikipedia (accessed 12 July 2012.)

7 “Minamitorishima,” Wikipedia (accessed: 12 July 2012).

8 Yukie Yoshikawa, “The US-Japan-China mistrust spiral and Okinawa,” The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, 11 October 2007.

9 Yoshikawa, ibid.

10 “Minamitorishima,” Wikipedia, op. cit.

11 See “Daito islands” in Wikipedia.

12 See “Okinotorishima no gaiyo,” the Tokyo Metropolitan site for Okinotorishima (accessed 12 July 2012).

13 “Status of Okinotorishima Island,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Press Conference, 18 February 2005 (accessed 30 August 2012).

14 International Crisis Group, Stirring up the South China Sea,” (2), Regional Responses, Asia Report No 229, 24 July 2012, p. 29.

15 Koh Choong-suk (president of Society of Ieodo Research), “About Okinotorishima,” Korea Herald, 15 May 2012.

16 For excerpts see UNCLOS, “Summary of Recommendation of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in regard to the submission made by Japan on 12 November 2008,” adopted by the Commission, 19 April 2012. p. 4,

17 In Yomiuri shimbun: “Tairikudana 31 man heiho kiro kakudai – Okinotorishima hoppo nado,” Yomiuri shimbun, 28 April 2012, and in Asahi shimbun: “Okinotorishima kai-iki no tairikudana enshin, Nihon shinsei kokusai kikan ni mitomeru,” Asahi shimbun, 28 April 2012.

18 “Okinotorishima kai-iki no tairikudana enshin,” op. cit.

19 UNCLOS, “Progress of Work in the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf,” Statement by the Chairperson, New York, 30 April 2012.

20 Cole Latimer, “Seabed Mining: Plunging into the depths of a new frontier,” Australian Mining, 10 August 2012.

21 “Large rare earth deposits discovered, valuable cache found within nation’s EEZ,” Yomiuri shimbun, 30 June 2012. For a scientific statement of the findings across the Pacific Ocean, Yasuhiro Kato et al, “Deep-sea mud in the Pacific Ocean as a potential resource for rare-earth elements,” Nature Geoscience, 4, 535-539, July 2012.

22 Quoted in James C. Hsiung, “Sea Power, Law of the Sea, and a Sino-Japanese East China Sea ‘Resource War’,” in James C. Hsiung, ed, China and Japan at Odds: Deciphering the Perpetual Conflict, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, pp. 133-154, at p. 144.

23 “Okinotorishima,” Wikipedia, (accessed 22 July 2012), http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Okinotorishima/

24 See chapter 11 of Gavan McCormack and Satoko Oka Norimatsu, Resistant Islands: Okinawa confronts Japan and the United States, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2012, pp. 209-222.

25 Leon Panetta, Secretary of Defense, United States, “The US Rebalance Towards the Asia-Pacific,” Keynote presentation to the First Plenary Session, The 11th IISS Asian Security Summit The Shangri-La Dialogue, Singapore, June 2, 2012.

26 “China’s Military Rise – The Dragon’s new teeth,” The Economist, 7 April 2012.

27 China is reported, however, to have considerable submarine and missile capacity, and the rate of expansion of military spending is certainly significant, increasing by six times over the past 13 years while US military spending heads towards contraction. (Demetri Sevastopulo, “US plans to boost Pacific naval forces, Financial Times, 2 June 2012.)

28 These notional lines may or may not reflect some corresponding Chinese strategic concepts, though the general thrust – to concentrate on establishing naval dominance within the First Line (its “near seas”), followed by freedom to manoeuvre within the Second (its “mid-far seas”), and eventual global naval presence – seems soundly based.

29 Anton Lee Woshik ll, “An Anti-Access Approximation: The PLA’s active strategic counterattacks on exterior lines,” China Security, Issue 19, March 2012.

30 Ishihara Shintaro, “The US-Japan alliance and the debate over Japan’s role in Asia,” lecture to Heritage Foundation, Washington D.C, 16 April 2012 .

31 One estimate of the rental revenue for the three islands for the decade from 2002 is “over 260 million yen.” Wani Yukio, “Barren Senkaku Nationalism and China-Japan Conflict,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 10, Issue 28, No. 4, July 9, 2012.

32 James C. Hsiung, “Sea Power, Law of the Sea, and a Sino-Japanese East China Sea ‘Resource War’,” in James C. Hsiung, ed, China and Japan at Odds: Deciphering the Perpetual Conflict, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, pp. 133-154, at p. 135.

33 Togo Kazuhiko, “Japan’s territorial problem: the Northern Territories, Takeshima, and the Senkaku islands,” The National Bureau of Asian Research, Commentary, 8 May 2012.

34 Martin Lohmeyer, The Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands Dispute: Questions of Sovereignty and Suggestions for resolving the Dispute, University of Canterbury, Master of Laws thesis, 2008, p. 66. (accessed 1 July 2012).

35 Details in McCormack and Norimatsu, pp. 211-214.

36 Jun Hongo, “Tokyo’s intentions for Senkaku islets,” Japan Times, 19 April 2012.

37 Ishihara, lecture to Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan, Tokyo, 29 May 2012. Matsubara Hiroshi, “Tokyo Governor calls out his enemies at FCCJ,” Asahi shimbun, 29 May 2012.

38 By majority vote on 19 April 2012. (Medoruma Shun, “Ryodo mondai ‘ ni nesshin na seijikatachi no usankusasa,” Uminari no shima kara, 24 April 2012.)

39 On 23 April. (Medoruma, ibid.)

40 Jun Hongo, op. cit. and (the opinion survey) “‘Shiji’ kennai 54%, zenkoku 61%,” Ryukyu shimpo, 9 May 2012.

41 “Senkaku konyu nara ‘judai na kiki,’ Chu Chu taishi ga hantai meigen,” Tokyo shimbun, 7 June 2012.

42 “Niwa chu Chugoku taishi ‘moshiwakenai,’ Senkaku hatsugen de shazai,” Asahi shimbun, 8 June 2012.

43 Segawa Seiko, “Senkaku tsuba no kokkai giin fukumu 120 nin no sanka,” Shukan kinyobi, 29 June 2012, p. 8. (Segawa points out that Ishigaki fishermen rarely venture to these islands because rising fuel prices – one way cost ca. 90,000 yen – have made it almost prohibitively expensive.)

44 “Ishihara delivers blistering attack on Senkaku issue,” Asahi shimbun, 12 June 2012.

45 “Senkaku kokuyuka,” op. cit. (The panda died of pneumonia shortly afterwards.)

46 “Senkaku Islands,” Wikipedia (accessed 22 July 2012).

47 “Taiwan man flubs disputed islands protest with flag mix-up,” The Wall Street Journal, 6 July 2012.

48 “Kyodo, “Government to make bid for Senkakus,” Japan Times, 8 July 2012.

49 “Govt reveals plans for Senkaku Islands,” Yomiuri shimbun, 21 July 2012.

50 “China must rein in provocative acts around Senkaku Ialands,” Asahi shimbun, 10 July 2012.

51 “China making waves again with Senkaku Islands incursion,” Yomiuri shimbun, 14 July 2012.

52 David Bandurski, “The flag that launched 1,000 headaches,” China Media Project, 16 August 2012.

53Naikakufu daijin kanbo seifu kohoshitsu, Gaiko ni kansuru seron chosa, Tokyo, Cabinet Office, October 2011 (accessed 21 August 2012).

54 “‘Kishimu Nitchu kankei’ Okinawa de shinrai seisei no ba ni,” Okinawa taimusu, 17 July 2012.

55 “‘Senkaku – Nihonjin joriku’ tairitsu no rensa o uchikire,” Okinawa taimusu, 21 August 2012.

56 “Japan ignores history lesson,” China Daily, 8 August 2012.

57 McCormack and Norimatsu, op. cit.

58 When Campbell committed the US to “defend Japan’s territory and areas under its jurisdiction”, the latter category clearly included Senkaku/Diaoyu. (Quoted in Mark Valencia, “The East China Sea Dispute: Context, Claims, Issues, and Possible Solutions,” Asian Perspective, 31, 1, 2007, pp. 127-167, at p. 155.

59 McCormack and Norimatsu, p. 212.

60 Jiji, “U.S.: Settle island rows via intl law,” Yomiuri shimbun, 24 August 2012.

61 Jun Hongo, op. cit.

62 Teddy Ng, “Ma makes first move on truce for Diaoyus,” South China Morning Post, 6 August 2012.

63 Lohmeyer, p. 63

64 Unryu Suganuma, Sovereign Rights and Territorial Space in Sino-Japanese Relations, Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 2000, pp. 87, 105. (Valencia, pp. 156-157, quotes from the imperial edict, said to be in the hands of the Sheng family in the US, but he too qualifies the story with words such as “reportedly” and “apparently.”)

65 “Senkaku kokuyuka’ tairitsu kaihi e no chie o shibore,” Okinawa taimusu, 10 July 2012.

66 Nogawa Motokazu, “Ryodo mondai ni atsuku naru uha rondan no tanjun shiko,” Shukan kinyobi, 25 May, 2012, pp. 16-17.

67 Kyodo, “Ad in Wall Street Journal seeks US support for Senkaku purchase plan,” Japan Times, 29 July 2012.

68 Mizuho Aoki, “Poster boasts metro plan to buy Senkakus,” Japan Times, 14 July 2012.

69 Kyodo, “Government offering Senkakus owner Y2 billion for contested isles,” Japan Times, 27 August 2012.

70 “Governor Ishihara reacts coolly to national govt’s plan to nationalize Senkaku islands,” Mainichi shimbun, 9 July 2012.

71 The former from “Senkaku purchase must be settled calmly in Japan,” editorial in Mainichi shimbun, 11 July, 2012 ,and the latter from “Stop infighting over the Senkakus,” editorial in Japan Times, 18 July, 2012.

72 In the Diet on 26 July 2012. See Takahashi Kosuke, “China, Japan stretch peace pacts,” Asia Times Online, 7 August 2012.

73 “Ultra-nationalist Ishihara provokes Japan’s neighbours,” The China Post, 30 August 2012.

74 For discussion of this point, Toyoshita Narahiko, “‘Senkaku konyu’ mondai no kansei,” Sekai, August 2012, pp. 41-49.

75 Toyoshita (ibid, p. 42.) quotes the Japanese government response to a Diet question in October 2010 asking why these islands remained under US control: although the US side had given no notice of intent to use the islands for bombing practice since 1978, it also “had not indicated its intention to return them.”

76 Toyoshita, pp. 44-45.

77 Yabe Teiji, Konoe Fumimaro, 2 vols, Kobundo, 1952, vol 2, pp. 559-560.

78 See my “The San Francisco Treaty at 60: the Okinawan Angle,” forthcoming in a volume to be edited by Kimie Hara of Waterloo University, Canada.

79 “Taking harder stance toward China, Obama lines up allies,” New York Times, 25 October 2010.

80 Mike Green, formerly Director of Asian Policy in the George W. Bush White House, and a continuing prominent Washington voice (quoted in Peter Hartcher, “China gets its catch, hook, line and sinker,” Sydney Morning Herald, 17 July 2012.)

81 International Crisis Group, p. 34.