Abstract: Like many world leaders, PM Shinzo Abe has not managed the COVID-19 outbreak very well. Back in early February, when the Diamond Princess cruise was transformed into a coronavirus incubator due to botched quarantine procedures, the alarm bell rang about the coming pandemic, but Abe dithered and downplayed the risk in an abortive attempt to save the Tokyo 2020 Olympics. The government tested relatively few people for the coronavirus leaving policymakers shooting in the dark. The health care system is in crisis due to inadequate preparations. Abe’s complacency and lack of leadership set the tone for Japan’s crisis response. Despite a relatively low number of deaths, public opinion polls indicate that most Japanese believe he declared a national emergency too late and has not handled the crisis well. Other leaders in East Asia have been more resolute, but so far Abe has not passed the pandemic leadership stress test.

Like many world leaders, PM Abe Shinzo has not managed the COVID-19 outbreak very well. Certainly, they all look better than President Donald Trump whose cringeworthy freak shows of misinformation and self-congratulation conjure a carnival barker selling snake oil. It beggars belief that Trump can top his bizarre suggestion to inject bleach to cure the coronavirus, but he has shown a great capacity for redefining the imaginable lowest low. More Americans have died in his corona war than during the entire Vietnam War, and yet the self-adulation continues as he bangs on about what a great job he is doing.

Other fumbling world leaders are grateful for these relentless Trumpian blunders because he makes everyone look better, even dolts like President Bolsonaro of Brazil. But the disaster of Trump doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t scrutinize other leader’s failings. A case in point is Japan’s slow-motion train wreck.

PM Abe declares National Emergency

Dithering Abe

On April 7 PM Abe Shinzo belatedly declared a national emergency in seven prefectures, almost a month after gaining the legal authority to do so, and on April 16 he extended this nationwide in the face of public pleas from prefectural governors and public opinion polls indicating broad dissatisfaction with his handling of the coronavirus outbreak. A mid-April Kyodo poll found that 80% think he waited too long to declare a state of emergency and his support rate dropped by 10 percentage points since early March to 40 percent. Abe’s tardy move was an acknowledgement that the half measures taken so far have not worked.

April was a tough month for Abe as the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases rose nearly tenfold to roughly 14,000. On April 7th Abe warned that if people didn’t practice social distancing there might be 80,000 infections in a month, so the situation might have been far worse. The number of deaths is also lower than feared at some 360 as of April 26, but as Americans recall, it only took the US one month to jump from 1,000 deaths to 54,000.

There are various explanations for Japan’s low number of Covid-19 cases. Handshaking, hugs and kiss greetings are rare, mask wearing is common, personal hygiene is high and public spaces usually kept clean. Public health announcements about handwashing and social distancing are also ubiquitous and taken seriously.

There is also speculation that Japan’s mandatory BCG vaccination policy to protect against tuberculosis might be helping as it has proven efficacious in protecting against other contagions, including various respiratory diseases. The correlations are intriguing, “Among high-income countries showing large number of Covid-19 cases, the U.S. and Italy recommend BCG vaccines but only for people who might be at risk, whereas Germany, Spain, France, Iran and the U.K. used to have BCG vaccine policies but ended them years to decades ago. China, where the pandemic began, has a BCG vaccine policy but it wasn’t adhered to very well before 1976 … Countries including Japan and South Korea, which have managed to control the disease, have universal BCG vaccine policies.”

It also seems that there has been serious underreporting of COVID-19 cases in Japan and that without more testing the scale of the outbreak remains uncertain. As Azby Brown at Safecast reports, “Very little of Japan’s testing and case reporting system is automated or fully online. Unbelievably, all of the data is still sent by fax, and needs to be manually transcribed, entered, and compiled. This introduces unnecessary delays and makes the likelihood of data entry errors higher.” He cites credible estimates suggesting that the actual number of COVID-19 cases is ten times the official figure, meaning some 140,000.

The Financial Times reports 60 percent underreporting of deaths from COVID-19 in many countries, not including Japan. Regarding Japan, Azby Brown reports that, “Recent mortality rate data from NIID indeed shows a statistical increase in influenza mortality in Tokyo in March and early April, 2020…this may include some undiagnosed coronavirus deaths. Again, this does not mean deaths are being intentionally hidden, but that the reporting system sometimes makes it difficult to determine with full confidence actual causes of death.”

Thus, it is too soon to know the scale of the outbreak and the number of deaths due to COVID-19, but current figures are most likely underreporting the actual toll.

Ambulance in front of the Diamond Princess cruise ship

It took a long time for Japan to take the risk seriously and even until mid-April, Tokyo’s bars, night clubs, izakaya and other restaurants and pachinko parlors were doing a brisk business. Back in early February, when the Diamond Princess cruise ship docked in Yokohama was transformed into a coronavirus incubator due to botched quarantine procedures, the alarm bell rang about the coming pandemic, but Abe hit the snooze button. There is growing evidence that the government did not use the early warning to adequately prepare.

Since February the Abe government has come under fire for limiting testing and downplaying the crisis in a desperate but abortive attempt to save the Tokyo 2020 Olympics. Abe saw this as a legacy project and the business community lobbied to keep the Games on track, banking along with Abe on an Olympic boost for a sagging economy. The stakes were high as total spending on hosting the Olympics came to an estimated $28 billion, while US$6 billion in sponsorship deals hung in the balance.

Abe also was eager to hold a planned summit with Chinese President Xi Xinping in April and thus tried to keep a lid on the crisis. So, for various reasons the Abe government exuded an unwarranted complacency about a brewing outbreak. He had company.

As late as March 25th the Japanese Business Federation (Keidanren) was expressing optimism about tracing and breaking the chain of transmission, two days after the Olympics were postponed, and just before the outbreak scaled up. Keidanren has the prime minister’s ear and stressed the pandemic’s severe economic repercussions. It opposed a strict lockdown, helping to explain the government’s foot-dragging throughout March.

Testing Suppressed

The official policy of limiting testing, making it very difficult for anyone to get a test, left the government shooting in the dark in trying to contain the outbreak while preoccupation with the Olympics slowed the pandemic response. The Japanese are now paying the price for this negligence. The Japan Medical Association (JMA) and other health experts have lobbied for increased testing since March, but the government stonewalled these requests.

In April the government did ramp up testing but as of mid-April Japan has conducted only 130,000 tests. By contrast, there have been 520,000 tests in South Korea, a nation with less than half the population. Yet, the number of people testing positive for the corona virus in Japan exceeds the total in South Korea, and there have also been more deaths.1

Clearly, President Moon has managed the outbreak much better than Abe and voters rewarded him in the recent parliamentary polls.

President Moon Jae-in’s party won a landslide victory in April 2020

Nobel laureate Yamanaka Shinya, director of the Center for iPS Stem Cell Research Application at Kyoto University, warns that Tokyo’s positive rate has become “very high” and that more testing is crucial so that policymakers can better understand the scale of the outbreak before it overwhelms the health care system. A week before Abe declared a national emergency on April 1st the JMA declared a medical system crisis. Yokokura Yoshitake, the JMA president, has criticized the government’s limited testing approach, focusing on clusters, and maintains that after it became difficult to trace transmission of more than half of those infected that policy should have been abandoned. He also points out that the criteria for judging whether to test an individual were overly restrictive. One guideline required individuals with a fever of more than 37.5 degrees to stay at home for four days before administering a coronavirus test, thereby facilitating community transmission and squandering precious time that could lead to fatalities.

The testing debacle has health experts on edge.

Brink of the Brink

Health experts warn that Japan’s healthcare system is on the verge of collapse.

The governor of Osaka pleaded for the public to donate raincoats because doctors, facing acute supply shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), were forced to resort to wearing trash bags as protective gear in dealing with COVID-19 patients.

In response, the local Hanshin Tigers baseball team donated 4,000 ponchos, perhaps not ideal but more than the central government has managed.

And at Tokyo’s gateway Narita Airport, after incoming travelers are tested, many are now forced to stay quarantined in cardboard boxes for a couple of days until they get the results.

Narita’s Cardboard box Quarantine Hotel

Raincoats and cardboard boxes? Really? This is not the meticulously prepared Japan most imagine. Cardboard boxes bring to mind the displacement centers in Tohoku back in March 2011 when people who had lost everything due to the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disasters created cardboard box villages and reestablished a sort of order and community. Then it seemed a sign of pluck and resilience, but welcoming mostly returning Japanese from overseas into cardboard boxes isn’t so uplifting. In contrast, those who arrive in Hong Kong airport are brought to a massive hangar quarantine facility, tested and get their results in eight hours. If negative, they are released with an electronic bracelet and told to remain at home for two weeks.

Many other nations also have personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages, but the plea for raincoats was shocking given that Osaka Prefecture at the time had just 900 COVID-19 cases. How could that overwhelm the healthcare system for the nation’s third largest metropolis in a prefecture of 9 million residents? It’s a national problem as hospitals in 43 out of 47 prefectures are already running out of coronavirus-care capacity. The fact that Japan has just half of the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) beds per 100,000 people as Spain while Germany has six times more and the US seven times more underlines the gravity of the problem.

Projections for a worsening shortage of ICU beds are not encouraging.

Ignoring early warning signs, the government failed to prepare adequately, leaving frontline healthcare workers to face great personal risk as they scramble to cope with an escalating outbreak.

Abe the Feckless

A majority of Japanese have become critical of Abe’s crisis management and in a recent Mainichi poll, 70 percent believe that he waited too long to declare an emergency, losing precious time to manage the outbreak. In the Asahi poll from April 18-19, 57% said Abe failed to provide leadership during the outbreak and 77% believe he should have declared a national emergency sooner.

Even the reliably pro-LDP Sankei recorded a 25 percent increase in public disapproval of Abe’s crisis management between the end of March and mid-April, with sixty-four percent faulting Abe’s handling of the virus outbreak. In declaring a limited state of emergency on April 7 Abe acknowledged the healthcare crisis, one that is a result in part of his unwarranted complacency about the pandemic. His complacency set the tone for the government’s tardy crisis response, leaving Japan the laggard in East Asia. Compared to resolute regional leaders in Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore and Vietnam, Abe dithered and failed the COVID-19 leadership stress test.

Team Abe has tried to hide behind an ostensible lack of authority to order a tighter lockdown and highlight his respect for Japan’s democratic values and constitutional constraints. This would come as a surprise to Okinawans and their recent governors who have tried to block Abe’s efforts to build a new U.S. Marine Corps Airbase at Henoko. Abe has ignored a referendum in February 2019 when 72 percent of islanders voted against building the base. Repeated public opinion polls indicate strong Okinawan opposition to base.

Abe’s hands are tied? Not apparently when he unties them. Abe’s cronyism scandals and cover-up, his nixing of a probe into unethical conduct of a party member related to gambling casinos along with postponing the mandatory retirement of the head of the Tokyo High Public Prosecutor’s Office are only a few examples of how Abe has bent the rules. And in 2015, when even Abe’s own handpicked constitutional scholars gave testimony in the Diet declaring his collective self-defense legislation unconstitutional, he brushed them aside and rammed the bills through the Diet.

So why is Abe so meek when it comes to imposing a strict lockdown to protect the people? Constitutional scholar Lawrence Repeta argues that Article 41 of the Constitution provides the government with the power to take more decisive action. After consulting various Japanese constitutional scholars, he concludes, “There is no doubt that reasonable restrictions calculated to limit the spread of the coronavirus pass constitutional muster.”

Since the government has the power to act more aggressively, as it did after the Fukushima nuclear disaster, why doesn’t Abe do more now? Politics. In early March Abe’s coalition passed a Special Measures Act (SMA) in the Diet that does not mandate any penalties for non-compliance with government lockdown requests. Abe’s coalition has supermajorities in both houses so it could have passed a bill with mandatory powers and penalties for non-compliance. Repeta argues that Abe’s quest for constitutional revision and desire for a national emergency amendment help explain why the SMA lacks teeth. By deliberately not acquiring such powers now, Abe hopes to strengthen the case for the LDP’s proposed constitutional amendment that would allow the Cabinet to suspend the Diet and rule by decree, free from awkward scrutiny and troublesome transparency. Repeta writes,” If Cabinet orders had the same effect as law, the nation could be ruled by secret government for as long as the declaration remained in effect.” Abe’s Holy Grail of Constitutional revision remains elusive, however, as public opposition remains strong.

The other wrinkle in the SMA is the decentralization of responsibility as the buck has been passed to prefectural governors, enabling the prime minister to duck blame. Under the SMA, governors have the responsibility for coping with the outbreak, but many prefectures lack adequate resources to respond effectively.

Covid-19 Briefing by Tokyo Governor Koike Yuriko

Tokyo stands out as an example of local initiative trumping the central government’s sluggish response, but even Governor Koike Yuriko has experienced pushback from Abe who remains reluctant to cede power. She clashed with him over more comprehensive shutdown measures while Abe, bowing to pressure from the business community, resisted doing so to avoid a tailspin in an economy already slipping into recession due to the consumption tax increase he imposed last autumn. Regarding Abe’s half-measures and resistance to her call for extensive shutdowns Koike complained, “I thought governors would get authority akin to a CEO but … I feel more like a middle manager.”

Wakayama provides another example of local initiative in containing the outbreak. The “Wakayama model” demonstrates how local leaders can seize the initiative by defying government policy on testing and tracing policies to win a local battle against the global pandemic.

As Simon Denyer observes, “It’s a lesson in how nimble thinking and concerted action — grounded in fast, well-targeted testing and tracing — can beat back the novel virus and break its chain of transmission.” The first infection at the end of January involved a doctor and soon thereafter Governor Nisaku Yoshinobu defied Health Ministry guidelines and protocols by insisting on testing the doctor’s colleagues and patients and those who came into contact with them to trace the path of transmission. This testing and tracing blitz proved effective and helped the prefecture bring the situation under control.

Civil society organizations are responding to the plight of the vulnerable and forgotten, as they usually do, but in the case of the homeless, what is the relevance of a stay at home order? Some see hope in neighborhood associations promoting social distancing even though less than 4 percent of under 30s participate.

Certainly, they contributed significantly to the emergency response in Tohoku following the 3.11 disaster, and may prove their worth once again, if only to create an atmosphere of self-restraint.

So not everyone is passively waiting for the government to act and Abe to take charge, but he set the tone early on by downplaying the risks and not taking urgent countermeasures. For example, the Wuhan outbreak and Diamond Princess provided good opportunities to step up vetting of travelers and impose extensive entry restrictions, but Abe was more concerned about not offending China and saving the Olympics than protecting Japan’s residents.

Communicating 101

At a time when the public sought clarity, Abe sent a mixed message in declaring a limited national emergency on April 7, stressing the need for social distancing to lessen transmission but in the same breath endorsing business as usual while offering a stimulus package that leaves many disappointed and others forgotten. His inconsistent messaging generated chaos and anger.

Subsequently, Abe flip-flopped on household support payments, from targeting the neediest to a one-time $900 payment for everyone. With no income replacement program, and limited telecommuting options for many workers, as of mid-April 60% are still commuting in greater Tokyo because they must, many riding trains where social distancing is impossible.

Another survey found that only 18% of people nationwide have stopped going to work as people balance the transmission risks of commuting against losing their incomes.

While teleworking is catching on at large firms, many small and medium size firms where some 70 percent of Japanese are employed, lack the capacity to support this.

Problematically, for some jobs, workers need to be there due to inflexible work rules and the physicality of their jobs. Furthermore, non-regular employment accounts for 38% of the entire workforce and many are paid hourly wages and lose income if they don’t show up.

There are signs of dissatisfaction. Abe has been savaged on social media for his mask distribution policy, dubbed Abenomasku (Abe’s masks), a pun on his sputtering Abenomics policy.

This meager gesture of mailing every household two cloth masks was announced soon after NHK aired a documentary that showed how Taiwan distributed masks far more efficiently and outperformed Abe’s crisis response across the board.

Adding to the furor, there have been massive recalls after numerous complaints about mold, insects, eyelashes and other signs of contamination in these imported masks.

Abe’s wife didn’t help matters by attending a cherry blossom party when everyone else was told to stay home. Then Abe tweeted a video of him coping with the lockdown by cuddling his dog, sipping tea and channel surfing, provoking a torrent of criticism zinging a leader failing to lead, seemingly oblivious to public anxieties and deprivations.

This is reminiscent of his blasé approach to lost pension records back in 2007 when he downplayed the issue and ignited a fierce backlash from worried citizens who hammered the LDP in the Diet elections.

At the time his sobriquet was KY (kūki yomenai), meaning clueless.

Leadership

In contrast to Abe’s sluggish and wavering response to the COVID-19 crisis, Tokyo Governor Koike Yuriko has shown Japanese what a leader looks like by communicating frequently with the public and providing reliable and useful information. As a former TV announcer, Koike has excellent communication skills and provides a reassuring presence with her no-nonsense online daily briefings with flip charts and stern warnings to stay home and shutdown businesses in order to avoid an explosive outbreak. She uses the mass media, social media, and YouTube to get her message out in Japanese and English while disseminating sensible advice about social distancing. She also funded a publicly accessible website to track and update relevant data on the corona virus outbreak that is available in Japanese, English, Chinese and Korean.

The contrast between her and Abe is stark, and she is winning the PR battle and having a positive impact on containing the outbreak. Abe has been remote to the extent that in February the media accused him of being AWOL. After polls showed declining support, Abe has tried to overcome negative perceptions, but he is a stiff and awkward communicator. Abe may be the Teflon premier, shrugging off numerous scandals that would have red-carded any other leader, and bouncing back from imploding support rates, but his luck may be running out. Abe is deservedly dogged by public ire about his “too little, too late” response to the outbreak.

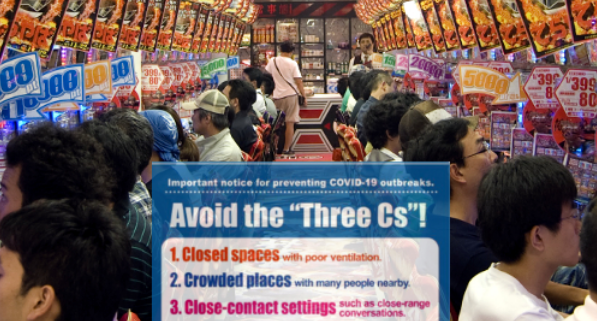

Pachinko Parlors remained open and packed

The Golden Week holidays have started but without the usual frenetic rush to the exits transport overload. Trains and planes are empty and streets eerily quiet. This after a concerted campaign to get people to stay home and refrain from travelling during the holidays. This self-restraint is just what is needed to curb transmission and shows that political leaders can use the bully pulpit to jawbone public compliance. This time, Abe took his cue from Koike and in the runup to the Golden Week exodus frequently reinforced her message to stay home. What if Abe had acted sooner and used his high-profile platform to encourage social distancing and ramp up testing and tracing in February when the outbreak was just starting? Had he been bold, he might have done a great service to the nation.

A leader can make a difference. When Kan Naoto was Health Minister in 1996, he demanded and received files that ministry bureaucrats had been hiding about meetings with pharmaceutical firms concerning tainted blood products that implicated them in Japan’s HIV-AIDS outbreak among hemophiliacs. He released the unredacted files to the media, earning transparency points while angering bureaucrats unaccustomed to being held accountable.2

Again in 2011 Prime Minister Kan acted decisively in dealing with the 3.11 triple disaster despite bureaucratic stonewalling and LDP machinations.

At that time he persuaded Chubu Electric to idle its Hamaoka Nuclear Plant despite having no legal authority to order closure. Sometimes a leader needs to act resolutely, especially when people’s lives are at stake.

Earlier this April, Abe and Koike were at odds as she lobbied for tougher measures while he fought a losing battle on behalf of business as usual. This contest made Abe look weak and beholden while Koike looked resolute in supporting the public interest. There is much debate about the tradeoff between public health and economic distress, but in taking the high ground of public health Koike has emerged in the eyes of many as the people’s champion while Abe looks somewhat craven. There are also scientific grounds to suggest that she is right in her priorities.

Keidanren appeared to have written the first draft of Abe’s stimulus package and will play a crucial role in both mitigating the economic dislocation and in the timing of the exit from Japan’s version of lockdown. In consultation with the Japanese Trade Union Federation (Rengo) and the government, Keidanren is encouraging member companies to maintain jobs by all possible means. Keidanren represents large enterprises, employing about 30 percent of the workforce, and they have vaults of cash that should help them ride out the pandemic. The situation is not so rosy for small and medium size firms where 70 percent of Japanese work. The government anticipates that the pandemic impact on unemployment may prove severe as shrinking demand at home and overseas will batter the economy. Suicide is a grim leading indicator of the misery index and is tragically on the rise.

Abe as Super Mario at Rio 2016 Olympics closing ceremony

Legacies

Abe has little to show for being Japan’s longest serving prime minister, having failed to deliver on numerous promises. He has been blessed with no serious rival in the LDP, a fractured and dysfunctional opposition, a crack PR team of spin doctors and was able to ride on the coattails of a robust global economy until that went south. In monthly NHK polls since 2013 among his supporters few admire his leadership qualities (15%) or policies (15%) while a majority say they support him because there is no alternative. Despite such tepid enthusiasm he remains in power even though his signature policies on constitutional revision, security, secrecy, transparency, nuclear reactor restarts, arms exports, militarizing ODA and labor regulations are not popular. Moreover, his womenomics policy is in shambles along with Abenomics. And, there has been no progress on territorial disputes with Russia, China and South Korea while he has been marginalized from diplomatic initiatives with North Korea.

The 2020 Tokyo Olympics were supposed to be the crowning achievement, a feelgood send-off, but now they are postponed, and in the absence of a vaccine, staging a normal Games in 2021 with spectators is looking doubtful. Adding insult to injury, taxpayers will also have to pay a few billion more dollars to cover the costs of postponement after learning that the Olympic bidding process was corrupt and that a former Dentsu executive distributed just over US$ 8 million in emoluments to help secure votes for Tokyo.

Leaders around the world are often prickly about criticism, even if it is limited, but Abe is fighting back. Buried in the government’s corona stimulus package is US$22 million to fund AI monitoring of his overseas critics so that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) can correct any “misunderstandings”.

Allocating taxpayer money to contain an exaggerated plague of criticism is indicative of a government that has handled this more as a PR challenge than a profound public health crisis. Apparently, international reporters are doing their job by conducting investigative journalism and publishing critical findings that the government prefers to bury. But unleashing MOFA’s cyber-dogs on the New York Times, Washington Post, Guardian or Financial Times won’t curtail critical commentary. It’s a waste of money and reflects poorly on the Japanese government. It should be using AI to better deal with the pandemic rather than massaging perceptions. Checking the outbreak, treating patients and helping all those whose lives have been derailed by this crisis should be the priority rather than going to war with the press.

Containing the COVID-19 outbreak is essential for the nation and how Abe will be remembered. The stakes are high. So far there appear to have been relatively few deaths in Japan due to the pandemic, but if Japan emerges from this outbreak without a large toll, Koike deserves far more credit than Abe for such an outcome. Let’s hope that Japan is fortunate and escapes worst case scenarios, but not forget that Abe’s crisis management has been somewhere between woeful and underwhelming.

Notes

For live data on the global pandemic, see COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University.