Abstract: About 16,500 people were sterilized under the now-defunct Eugenic Protection Law (1948-1996) of Japan, whose aim was to “prevent the birth of eugenically inferior offspring, and to protect maternal health and life”. Kita Saburō (pseudonym), was one of the victims. He was sterilized in 1957, at the age of fourteen, while residing at a facility for troubled youths called Shūyō Gakuen in Sendai. This article introduces Kita’s testimony about his sterilization, and offers possible explanations of why Kita, who had no disability, was forcibly sterilized.

The interview was conducted on September 12, 2019 in Kita’s house in Nerima ward, Tokyo. Interview and translation by Astghik Hovhannisyan.

Introduction

It is a warm autumn day. I met Kita Saburō at a train station in Nerima ward of Tokyo, and we took a short bus ride to his house, where he lives alone. Kita’s wife passed away six years ago, and he has no children. At the age of 14 he was sterilized without his knowledge under the now-defunct Eugenic Protection Law (1948-1996). Kita is an energetic, friendly and likeable person, who has worked hard his whole life. He is also talented at crafts, especially at making paper flowers. Kita was born in Sendai in 1943. When he was 13, he was expelled from school and taken to Shūyō Gakuen, a facility for delinquent youths, where he was sterilized. He is now one of almost two dozen people fighting for damages against the Japanese government over forced sterilizations. “I thought I was sterilized by my family and the facility. Only recently I found out that I was sterilized by the state,” said Kita.

In recent years, a number of journalists and researchers (e. g. Mainichi shinbun shuzaihan 2019, Toshimitsu 2016) have introduced testimonies of victims of forced sterilization, but the topic is underrepresented in English, with Nagase’s (2019) work being the only one to introduce the voices of several victims.

This article briefly introduces the Eugenic Protection Law, and Kita Saburō’s reflections about his life, the facility for delinquent youths where he spent his early teens, and his forced sterilization. The article also attempts to explain the possible reasons why Kita – who has no disability – could have been targeted for forced sterilization.

The Eugenic Protection Law (1948-1996)

As mentioned above, Kita was sterilized under the Eugenic Protection Law (Yūsei hogohō), whose aim was to “prevent the birth of eugenically inferior offspring, and to protect maternal health and life” (Norgren 2001, 145). The bill was first introduced in the Diet in 1947, by socialists Ōta Tenrei, Katō Shizue and Fukuda Masako, amid fears of overpopulation and “reverse selection”, i.e. the fear that population “quality” would deteriorate if “unfit” people procreated uncontrollably (Matsubara 1998). The Socialists’ bill was shelved, but it was rewritten and reintroduced to the Diet in 1948, and Taniguchi Yasaburō, a physician, parliament member, and an influential figure in population policies since the prewar period became one of the main proponents of the law. In presenting the bill to the Diet, he insisted that Japan needed to promote family planning, but in order to prevent the “reverse selection” (gyaku tōta) caused by uncontrolled reproduction of the “unfit,” it also needed to take eugenic measures (Proceedings of the House of Councilors, June 23 1948).

The bill passed without much discussion the same year, and it allowed 1) abortion under certain circumstances – such as poor health, numerous children in the family, and economic reasons, and 2) voluntary and involuntary eugenic operations (sterilizations) of people having various genetic and non-genetic ailments and conditions.

This was not Japan’s first eugenics law. The first – the National Eugenics Law – was enacted in 1940. However, unlike the Eugenic Protection Law, it did not aim to constrain population growth, but instead encouraged it. Faced with issues such as overpopulation, economic hardship, health risks from “backyard” abortions after the war, Japanese lawmakers made a decision to authorize abortion (although without abolishing the Criminal Abortion Law of 1907). At the same time, fearful that Japan was facing “reverse selection” or degeneration due to uncontrollable reproduction of the “unfit,” they strengthened eugenic provisions as well (Matsubara 1997, Matsubara 1998).

In the Eugenic Protection Law, eugenic operations were authorized by Articles 4 and 12. Article 4 stated that in case a physician confirmed that the patient suffered from one of the hereditary conditions listed in the appendix, he or she could apply for a eugenic operation. The illnesses listed included hereditary mental deficiency, schizophrenia, manic-depression, progressive muscular dystrophy, hemophilia, and others. Article 12, which was amended in 1952, stated that in cases when the physician had the permission of the patient’s guardian, he or she could apply for permission to perform a eugenic operation on people having non-hereditary mental illness and mental retardation.

The law authorized physicians to apply for sterilization to prefectural Eugenic Protection Commissions, when they recognized that it was necessary. The Commissions, organized by prefectures and consisting of about ten members of various professions – physicians, social workers, scholars – would evaluate the applications together with family and medical histories of the patient, and make a decision about the necessity of forced sterilization (Hovhannisyan 2020). The Ministry of Health and Welfare authorized use of methods such as anesthesia, physical restraint, and deception, in case the patient opposed the operation (Yūsei shujutsu ni taisuru shazai o motomeru kai 2018, 268-269). It should be noted that from the inception of the law the Ministry of Health and Welfare was concerned that forced sterilizations might constitute a violation of human rights as guaranteed by the constitution. The Ministry of Justice gave assurances, however, that if the sterilization was in the public interest, the law would by no means violate the spirit of the constitution (Hōmu sōsai iken nenpō 1949). From 1949 to 1996, about 16,500 people were forcibly sterilized, with most operations performed in the 1950s and 1960s. 70% of those operated on were women, the majority of whom had mental illness or intellectual disability (Toshimitsu 2016, 11-12). Most operations took place in Hokkaido and Miyagi Prefecture, which may be explained by a relatively large number of mental health care institutions in these prefectures and regional policies promoting eugenic programs.

The law was abolished, or, to be more precise, replaced with the Maternal Body Protection Law (botai hogohō) only in 1996, after disability rights activist Asaka Yūho’s speech at the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo (1994) sparked international criticism. Immediately after that, a group of activists and scholars demanded that the Ministry of Health and Welfare investigate forced sterilizations and compensate the victims. The Ministry, however, refused to do so, stating that the operations were legal at the time they were performed (Ichinokawa 1998).

The issue was practically neglected for two decades, but in 2017 several victims started to speak out. It would be no exaggeration to state that the massacre of disabled persons in Sagamihara in 2016 had an impact on this, as the tragedy prompted discussions about disability discrimination and eugenics. After watching learning about the Eugenic Protection Law on the internet, Sato Michiko (pseudonym) from Miyagi Prefecture contacted the hotline to consult about her sister-in-law, Yumi (pseudonym), who was forcibly sterilized when she was 15. Sato Yumi became the first person to sue the Japanese government over forced sterilization in January 2018. Several others followed suit, and currently 24 people, including spouses of victims, have brought actions against the government.1

Lawsuits, and the public outcry that followed them, prompted the authorities to investigate the documents of forced sterilizations, and create a compensation law, which was enacted in April 2019 and allows victims to seek compensation of 3.2 million yen. It left, however, many of the victims and supporters unsatisfied, as it does not specify the state as the main perpetrator. Also, in May 2019 the Sendai District Court ruled the Eugenic Protection Law unconstitutional, but refused plaintiffs Sato Yumi and Iizuka Junko’s (pseudonym) claim for compensation, stating that the twenty-year statute of limitation had expired. However, it is important to add that most victims were not in a position to file lawsuits, for instance, twenty years ago, as many of them simply did not know that eugenic sterilizations were state-sanctioned, or were afraid of the stigma of being associated with them.

Kita Saburō was among 1,406 people sterilized in Miyagi Prefecture. It was in 1957, when Kita was a 14-year old student in a facility for “delinquent youths” called Shūyō Gakuen. He had none of the ailments or disabilities listed in the Eugenic Protection Law.

Shūyō Gakuen

Shūyō Gakuen was a facility for “delinquent youths” in Miyagi Prefecture. The history of institutions nowadays known as children’s self-reliance support facilities (jidō jiritsu shien shisetsu) can be traced to the Meiji period, when, with the perceived increase in the number of delinquent youths, Japan enacted the Reformatory Law (kanka hō) in 1900, according to which each prefecture was to establish a reformatory (kankain) (Ambaras 2005). The law was later replaced by the Juvenile Training and Education Law (shōnen kyōgo hō, 1933) and the Child Welfare Law (jidō fukushi hō, 1948). The facilities were subsequently renamed as juvenile training and education schools (shōnen kyōgoin) and children’s self-reliance support facilities (jidō jiritsu shien shisetsu) (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. 2014).

Shūyō Gakuen in 1939 (Fuji shuppan 2009, 190).

Shūyō Gakuen was established on Kanoko Shimizu-dori in Sendai in 1909. The Reformatory Law was enforced in Miyagi Prefecture in 1908, and the following year Shūyō Gakuen was established as the prefecture’s first state-run reformatory. During its first year, it operated in a private house (minka), moving to its own building in 1910 (Nihon tosho sentā 2003, 36). At that time, it could accommodate only ten children, while by 1939, when it celebrated its 30th anniversary, the total number of children (since its establishment) had reached 109, among which 103 were male and 6 female. In the prewar period, the children’s typical day involved waking up at 5 or 6 a.m. (depending on the time of the year), washing, cleaning, exercising, eating, reflecting on their behavior, studying (there was an individual plan for each student), learning practical skills such as farming or handicrafts, doing sports, and helping with various activities. Children were not spared such activities as hoisting the Hinomaru flag every morning and singing the national anthem as well (Fuji shuppan 2009, 200-201). When Kita Saburō was in Shūyō Gakuen in the 1950s, the everyday life of the facility was little different from this, as it involved studying, farming, helping with various tasks, etc. The number of children 34 at the time. There were several dormitories for children and teachers, a sports ground, a cookhouse, a workshop, several fields for farming, and an apple garden. In 1964, the facility moved to a new location and was renamed as Sawarabi Gakuen.

“Delinquent Youths” and Eugenic Sterilizations

Kita Saburō was sterilized in Shūyō Gakuen in 1957, as were several other children, according to his testimony. Why did Shūyō Gakuen subject some of its students to eugenic operation, if the Eugenic Protection Law clearly stated that only people having conditions listed in the Appendix, as well as those with non-hereditary mental conditions could be forcibly sterilized?

In the absence of documentary evidence, one may only speculate about possible reasons. One possible answer may be the broad interpretation of “inferior offspring” (furyō na shison), whose birth the Eugenic Protection Law sought to prevent, to include delinquents and criminals. In the prewar period, proponents of forced eugenic sterilizations often listed delinquency, alcoholism, and pauperism as “dysgenic” conditions (Fujino 1998, 161-176), and although the Eugenic Protection Law did not include any of these, in the early postwar period such attitudes might have remained. Another possible answer may lie in the perceptions of juvenile delinquency and its association with “low intellect” or “feeblemindedness.”

Discussions about the nature of juvenile delinquency and studies on that topic were frequent in the early 20th century, as Japan’s rapid industrialization and urbanization brought increased reports of crime and poverty (Ambaras 2005, 32-33). The existence of delinquent youths (furyō shōnen or hikō shōnen) was explained by many factors, such as poverty, influence of the family and the environment, genetics, social status, occupation, and physical and mental health. It was also frequently associated with “feeblemindedness” or seishin hakujaku, a term that included both what we now call intellectual disability and developmental disability. As Sakuta demonstrates, influential psychiatrists such as Tokyo Imperial University professor Kure Shūzo (1865-1932), his disciple Miyake Kōichi (1876-1954) and several others often connected juvenile delinquency with “idiocy” (Sakuta 2018, 105-112). Legal professionals often expressed similar opinions as well. For instance, bachelor of law Gotsu Shigeki wrote that criminals often had feeblemindedness (seishin no hakujaku) and were of low intellect (chinō no teikaku) (Gotsu 1922, 202-203). Judge Suzuki Kaichirō also claimed that “mental abnormalities were connected with juvenile crimes” (Suzuki 1923, 151).

It is probably not surprising that in 1932 Shūyō Gakuen started to conduct psychiatric diagnoses (seishin kanbetsu) of its students. Marui Kiyoyasu (1886-1953), professor of Tohoku Imperial University who was entrusted with this, was also supportive of the theory that juvenile delinquents had defective intelligence. In The 30-year History of Shūyō Gakuen, he looked back on his medical practice at the facility, writing: “I was entrusted as a physician of psychiatric diagnosis for Shūyō Gakuen students in 1932, and since then I have examined forty students, which is the same as the total number of students in this facility during that period. [……] Among those forty students, there were only three who demonstrated normal or average intellect. I have to conclude that the others were congenital imbeciles (sententeki teinōsha) .” (Fuji shuppan 2009, 193-194). Marui complained that society was insufficiently interested in this problem, adding that among 100 million population of Japan there was a surprisingly large number of “congenital imbeciles”, who could potentially become a burden for their families and for society (Fuji shuppan 2009, 194).

In the postwar period, studies on juvenile delinquency often out the limitations of intelligence tests and were more cautious about associations with mental disabilities, but many studies presented data showing that a certain number of delinquent youths had intellectual disability or mental illness (e. g. Higuchi 1953, 191-245). The intellectually disabled were the most likely targets of forced sterilization, as they were perceived as “unable to look after themselves”, “unable to control their sexuality”, and so on (Hovhannisyan 2020).

Victims’ Families

Kita Saburō’s testimony also reveals the complex nature of his relationship with his family, particularly his father. Kita is hardly the only victim of forced sterilization who shows resentment toward his family: Sora Hibari (pseudonym), Kobayashi Kimiko, and Kojima Kikuo, all of whom started lawsuits against the government, have also spoken about the difficult relationship with their families. In fact, many of the victims, who did not even know about the existence of the Eugenic Protection Law, blamed their families for their forced sterilization, indeed, some families initiated the sterilization, or at least passively consented to it.

How can we explain this? Were families “agents” of the state (i.e. taking on the role of discriminating against and excluding their children from society (Yōda 1999, 77-78))? Or, overburdened and lacking financial resources, were they themselves victims of circumstances? This paper is unable to answer this question, but research shows that families of disabled or unusual children often internalize societal prejudices, and unless they are conscious of it, they might become perpetrators of discrimination against their own children (Yōda 1999, 35-36).

Kita Saburō’s Reflections on his Life: Family, Child Support Facility, Inability to Have Children

Kita Saburō in his house (photo by the author).

Family

I was three years old when my father came back from the war. I saw an unfamiliar man, and I didn’t even think he was my father. I tried to be friendly, saying “Hi, uncle!”, but he just hit me. Then he looked into my face and said “I’m your father”. He said that and then hit me again, and it hurt a lot. I wasn’t a crybaby, but I thought “What a scary father”. After that I always thought that my father was scary. My grandmother saw that, she came up to me and said, “That must have hurt. This is your father”. I didn’t know anything about him before that. My mother died when I was eight months old, and my grandparents brought me up. I was three, and I was only starting to understand what was going on around me, when my father beat me. He was scary. I couldn’t become attached to him.

When I was in the 3rd year of elementary school, my father got married. One year later, my brother was born. If it had been a girl, my life might have been very different. A sister would marry into a family, and she would not take over the house. I already had an elder sister. But with a brother, that was not the case. I only had one parent, while he had two, so it was assumed that he would be the one to take over our house.

When I was in the 6th year of elementary school, I started studying very hard in order to be able to go to high school. There were no cram schools then, so I studied by myself. I would sometimes study till late at night. One night, my father came home and he asked, “What are you studying?” I said that I was studying to go to high school. But my father said, “Compulsory education is till middle school. The 3rd year of middle school. You don’t need to go to high school, stay at home and help us with the shop.” I begged him to let me go to high school, but he said he did not have money. I became rebellious after that.

Shūyō Gakuen and Sterilization

In middle school, I was quite strong. I wouldn’t lose if I got into fights. There was one student in our class who could not walk properly, and some bullies called him “a crippled turkey”. Once I got really angry and beat those bullies. But the teacher scolded me, saying, “You always cause problems.” Before I dropped out of school, I got into a fight again. I was with friends, but they managed to run away, and only I was caught. The teacher scolded me again, and told me to bring my parents to school. When they came, the principal told them, “He has done this a few times already”, and I was expelled from school. Then my teacher called the child consultation center, and told them I had been expelled from school. A few days later a teacher arrived from the consultation center, and took me there. I spent 2-3 days at the center, after which I was sent to Shūyō Gakuen. To be honest, I was happy to have been sent there. I wanted to leave my family home. My younger brother was to inherit the shop, he had two parents, while I had one. I thought it would be better if I left.

I recently returned to Shūyō Gakuen. I took a taxi, and got out of it near Mukoyama Elementary School. Everything was gone, Shūyō Gakuen, the senior citizen’s home, the apple gardens. There was only grass growing everywhere. Before we had apple gardens, flower beds with dahlias, lilies, sunflowers, chrysanthemums. Now everything was gone, buildings as well.

I used to live in Hikari dorm. There were three rooms, and three students lived in each of them. There was a small garden nearby, where we used to dry our clothes. Kitei-en, a facility for disabled children, was nearby. Once there was a fire there, it burnt down, and Kitei-en people lived in our dormitories for a while, until their new building was ready.

I was 14, just before the teacher took me to the clinic and had me operated on, when my stepmother and my father came to visit. I think it was spring. I was surprised, trying to grasp why they came. My mother was wearing a kimono. I was afraid they came to take me home, and I was prepared to escape if that was the case. But they only talked with the principal, I think they were talking about my operation. Shortly after that, a teacher from Hikari dormitory took me to a clinic in Atago, where I was operated on. They didn’t tell me what surgery it was, the doctor just said he was removing something bad. It hurt a lot. I couldn’t even walk properly for about a week. I had no idea what operation it was until I heard that one of the seniors was sterilized, and realized that my operation was that as well. Two students of Shūyō Gakuen were sterilized before me, and three or four of them after. Kids from nearby Kitei-en were sterilized as well. I think they [the social workers] had a quota and they sterilized students indiscriminately. I was very healthy; I could do any physical work. I didn’t know about the eugenics law, and I thought my parents and social workers put me under the knife.

Life in Tokyo and Marriage

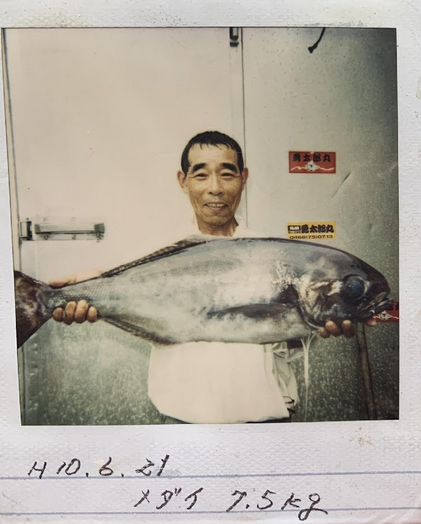

Kita at 55, holding the 7.5 kg Japanese butterfish he caught (photo provided by Kita Saburō).

When I graduated from Shūyō Gakuen, I worked in Sendai for a while. I lived in the company dormitory on the 2nd floor of the building. I got about 3000-6000 yen a month, and sent more than half of that to my father. Then one day my father demanded I return home. I didn’t want to, but I had no choice. One day I had an argument with my father, and he beat me again. I decided I had had enough, and that I needed to leave. I went to a few friends, borrowed 1000 yen from each of them. I figured if I had 3000 yen, I could go somewhere far away. I took a Joban line train. It was a Steam Locomotive, a steam train, can you imagine? I think it took about 12 hours. The place I arrived at was Tokyo. I was a stranger in this city, I didn’t know where to go, and as I was wandering about, a policeman from Ueno police department detained me. He told me to go to Ueno child consultation center, but I didn’t go there. I walked to Kanda, where I saw a curry shop that was looking for staff. I asked them to hire me, and they did. After that I worked in many places. I’m skilled with my hands, I can do any kind of manual work.

When I was in my late twenties, I had a job in Kitaharacho, which is not far away from this place [Nerima]. I was installing water pipes underground, and living in an apartment which was only a five-minute walk from the office. I had decided that since I cannot father children, I shouldn’t get married, but my master’s wife would always persuade me to do so. I would always say I had no intention to get married, but once she convinced me to go out with a woman, who was the daughter of her acquaintance. We met at a coffee shop, then went to a sushi place. I told her she could eat as much sushi as she wanted. We talked a lot. I had decided to remain single, but I ended up getting married. I was 27 then. I didn’t invite my family to the wedding, only my company president and his wife. I hardly ever contacted my family. Once my father asked me to send him 300,000 yen to send my younger brother to high school. I did, but hardly kept in touch after that.

My married life was fun for the first month, but people started bothering us with questions. Relatives, brothers and sisters would always ask, “When are you going to have children?” I thought, “I shouldn’t have gotten married”. My wife suffered a lot as well. Once I went to a gynecologist and asked if it was possible to restore my reproductive ability. He said he couldn’t do anything, but told me to go to the clinic in Sendai where I was operated on, to see whether they can do something. I never went to Sendai though, as the doctor said reversing the operation was probably impossible.

I didn’t have the courage to tell my wife about my sterilization until we were old. She got seriously ill. As the illness was progressing, and she was getting weaker and weaker, I decided to tell her about it. “I have a secret to tell you. When I was a child, my parents made me have a surgery that wouldn’t let me have children. I knew I couldn’t have children, but I married you. I am really sorry. ” I told her everything about Shūyō Gakuen and the operation. I thought she would scold me, but she just said, “Make sure you always eat well”. She died the next morning, at 5:55.

The Lawsuit

Kita (second from the right) speaking at a meeting after court hearings on January 16, 2020 (photo by the author).

On January 31 (2018), I read about the lawsuit [Sato Yumi’s suit against the Japanese government] in a newspaper. I was having lunch, but when I read the article I froze. I didn’t even know what a eugenic operation was, but it turned out it was the one I was subjected to as well. I contacted the hotline in Sendai, and they introduced lawyers in Tokyo. I wasn’t aware that sterilizations were being performed by the authorities. I had thought it was my parents and Shūyō Gakuen who were to blame. I talked with lawyers, and decided to file a lawsuit against the government.

To be honest, the compensation is not that important to me, I just want the authorities to apologize for the injustice. There are thousands of us, who were sterilized under this law. If we act alone, they can break us like disposable chopsticks. But if we unite, we will become a large tree, and no one can break us.

References

Ambaras, David. 2005. Bad Youth: Juvenile Delinquency and the Politics of Everyday Life in Modern Japan, University of California Press.

Fuji shuppan. 2009.” Shūyō Gakuen no sanjū nen” [The 30-Year History of Shūyō Gakuen]. In Kodomo no jinken mondai shiryō shūsei: senzen hen [Collection of Materials Concerning Human Rights of Children: Prewar Period] Volume 6, Tokyo: Fuji shuppan, pp. 189-216.

Fujino, Yutaka. 1998. Nihon fashizumu to yūsei shisō [Japanese Fascism and Eugenics]. Kyoto: Kamogawa shuppan.

Gotsu Shigeki. 1922. Furyō shōnen ni naru made [Becoming a Delinquent Youth]. Hyogo: Ganshodo.

Higuchi, Kōkichi. 1953. Sengo ni okeru hikō shōnen no seishin igakuteki kenkyū: Sengo hikō genshō no tokushusei no bunseki [A Psychiatric Research on Juvenule Delinquency in the Postwar Period: Analysis of Characteristics of the Postwar Delinquency Phenomenon]. Tokyo: Hōmu kenshūsho.

Hōmu sōsai iken nenpō. 1949. ‘Yūsei hogohō ni kansuru gigi ni tsuite [Questions on the Eugenic Protection Law].’ Hōmu sōsai iken nenpō 2, pp. 331-332.

Hovhannisyan, Astghik. Forthcoming 2020. “Preventing the Birth of ‘Inferior Offspring’: Eugenic Sterilizations in Postwar Japan”. Upcoming in Japan Forum.

Ichinokawa, Yasutaka.1998. “Omei ni mamireta hitobito” [People Tainted with Dishonor]. Misuzu 40 (8), pp.14-22.

Mainichi shinbun shuzaihan. 2019. Kyōsei funin: Kyū yūsei hogo hō o tou [Forced Sterilizations: Questioning the Eugenic Protection Law]. Tokyo: Mainichi shinbunsha.

Matsubara, Yōko, 1997. “‘Bunka kokka’ no yūseihō: Yūsei hogohō to kokumin yūseihō no dansō” [The Eugenic Law of the ‘Cultural Nation’: The Difference between the Eugenic Protection Law and the National Eugenics Law]. In Gendai shisō 25 (4), pp. 8-21.

Matsubara, Yōko. 1998. Nihon ni okeru yūsei seisaku no keisei: kokumin yūseihō to yūsei hogohō no kentō [Formation of Eugenic Policies in Japan: An Examination of the National Eugenics Law and the Eugenic Protection Law]. Doctoral dissertation: Ochanomizu Women’s University.

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. 2014. Jidō jiritsu shien shisetsu un’ei handobukku [Management Handbook for Children’s Self-reliance Support Facilities], pp.15-20. (accessed 17 November 2019)

Miyagi-ken Kitei-en. 1980. 30 nen no ayumi [30-year History of Kitei-en]. Kiyagi-ken Kitei-en.

Nagase, Osamu. 2019. “Voices from Survivors of Forces Sterilizations in Japan: Eugenic Protection Law 1948-1996”. In Maria Berghs, Tsitsi Chataika, Yahya El-Lahib, Kudakwashe Dube (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Disability Activism, Abington: Routledge, pp. 182-189.

Nihon tosho sentā. 2003. Shakai fukushi jinmei shiryō jiten [Biographical Dictionary of Social Welfare] Volume 2. Tokyo: Nihon tosho sentā.

Norgren, Tiana. 2001. Abortion Before Birth Control: The Politics of Reproduction in Postwar Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sakuta, Seiichirō. 2018. Kindai Nihon no shōnen hikōshi: “Furyō shōnen”kan ni kansuru rekishi shakaigakuteki kenkyū [A History of Juvenile Delinquency in Modern Japan: A Socio-Historical Study of the Images of “Bad Youths”]. Okayama: Gakubunsha.

Suzuki Kaichirō. 1923. Furyō shōnen no kenkyū [A Study of Juvenile Delinquency]. Tokyo: Daitokaku.

Toshimitsu, Keiko, 2016. Sengo Nihon ni okeru josei shōgaisha e no kyōseiteki na funin shujutsu [Forced Sterilizations of Disabled Women in Postwar Japan]. Kyoto: Research Centre of Ars Vivendi, Ritsumeikan University.

Yamamoto, Tatsuichi. 1981. Yamamoto Takeyoshi ikōshū [Posthumous Manuscripts of Yamamoto Takeyoshi]. Yamamoto Takeyoshi ikōshū kankōkai.

Yōda, Hiroe. 1999. Shōgaisha sabetsu no shakaigaku: jendā, kazoku, kokka [The Sociology of Disability Discrimination: Gender, Family, the State]. Tokyo: Iwanami shoten.

Yūsei shujutsu ni taisuru shazai o motomeru kai (ed.). 2018. Yūsei hogohō ga okashita tsumi: Kodomo o motsu koto o ubawareta hitobito no shōgen [The Crime Committed by the Eugenic Protection Law: Testimonies of People Who Were Denied the Right to Have Children]. Tokyo: Gendai shokan, pp. 268-269.

Notes

Information about lawsuits and plaintiffs can we found on the Defense team’s homepage. http://yuseibengo.wpblog.jp/