This article is based on a talk that Satoko Oka Norimatsu gave at the seminar “The ‘History Wars’ and the ‘Comfort Woman’ Issue: Revisionism and the Right-wing in Contemporary Japan, U.S., and Canada,” held at the Institute of Asian Research, the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, BC), hosted jointly by the Centre of Korean Research and the Centre for Japanese Research, on November 21, 2019.

Event poster by the Centre for Korean Research and the Centre for Japanese Research, University of British Columbia

Introduction

I am going to discuss the “history wars” in Canada, 2015 – 2018, building on Tomomi Yamaguchi’s illustration of Japanese history revisionism and its intervention seeking to block overseas memorialization of Imperial Japan’s system of military sex slavery.

In 2015, Burnaby, a city of about 220,000 people to the east of Vancouver, planned to erect a “Girl Statue for Peace,” in Central Park, one of the city’s public parks, in conjunction with its Korean sister-city Hwaseong. The plan, however, met heavy opposition from the Consulate-General of Japan in Vancouver, the right-wing within Japan, and local residents influenced by them. Hwaseong City’s statue eventually found a home across the continent, at a Korean-Canadian facility in Toronto.

From 2016 to 2018, members of provincial legislatures of Ontario, Manitoba, and British Columbia attempted to establish December 13 as the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day (NMCD), as 2017 marked the 80th anniversary of the atrocity in which hundreds of thousands of Chinese POWs and civilians were massacred and women and girls were raped and murdered by the Imperial Japanese Army that conquered Nanjing and surrounding areas. These efforts faced adversary pressures from the Japanese government and Japanese nationalists in Japan and Canada, but on October 26, 2018 Soo Wong, a member of the Ontario Legislature, succeeded in gaining unanimous support for the NMCD motion (Motion 66). At the federal level, on November 28, 2018, a member of Parliament, Jenny Kwan, tabled a similar motion. It did not pass, but Prime Minister Justin Trudeau recognized the importance for Canadians to remember this history.

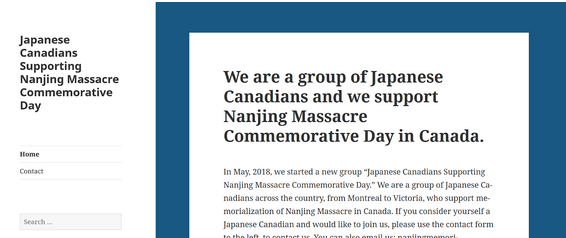

I was not just an observer of these events but a participant in the 2015 debate over the Comfort Women statue in Burnaby and the 2018 effort to proclaim a federal Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day. In 2015, I initially sought to provide a “bridge” between members of the Korean-Canadian community who wanted to build the statue and members of the Japanese-Canadian community who wanted to prevent it. Eventually, I became part of the “Peace Statue Committee,” which the Korean-Canadians formed, including members of the Japanese-Canadian, Chinese-Canadian and other ethnic communities. In 2018, I formed the Japanese-Canadians Supporting Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day to counter the Japanese government and Japanese nationalist opposition.

My position was two-fold. One was to oppose opposition to the commemoration: First, I thought it would be shameful for people with Japanese ancestry to actively oppose memorialization of Imperial Japan’s dark past. Second, I felt compelled to condemn the historical denial that was behind such opposition. Could we imagine German-Canadians staging an organizational protest against commemoration of the Holocaust in Canada, claiming that the historical claims of the event were groundless? It was necessary to demonstrate that some Japanese-Canadians1 were engaged in such nationalistic opposition and historical denial.

2014-2015: The “Comfort Women Statue” Plan in Burnaby, British Columbia

The Korean War Memorial at Central Park, Burnaby. Photo by author.

The planned site for the “Comfort Women Statue” for Burnaby, BC was on the western edge of the 86-acre Central Park, facing the Boundary Road, which borders the neighbouring city of Vancouver. A Memorandum of Understanding was signed between Burnaby and Hwaseong in the fall of 2014, and plans were underway to build the statue near the Korean War Memorial, which honours the 36 servicemen from British Columbia who died in the Korean War (1950-53).

According to the Sankei Newspaper,2 the Japanese government was aware of this plan as early as September of 2014, but the knowledge became public when the Hankyoreh Newspaper in Korea reported “Hwaseong City, of Gyeonggi Province is going to erect a ‘Girl Statue for Peace’ that honours the victims of the Japanese military sex slavery and wishes for world peace, in its Canadian sister-city Burnaby,” in its March 6, 2015 edition.3

Japanese rightists reacted swiftly. Nadeshiko Action, a women’s right-wing group, based in Japan, which denies the history of Japanese military sex slavery, called on the public to support a petition campaign opposing the statue on Change.org.4 The petition collected over 13,000 signatures by mid-April (from the comments section, it appears that most supporters were from Japan). It also encouraged sending emails to the City of Burnaby by providing five letter templates in English.5 As a result, thousands of emails swarmed the inbox of the Burnaby Mayor’s Office.

Otaka Miki, a conservative journalist alerted her audience on the Internet-based Channel Sakura by saying that the “innocent Japanese children will be bullied” as a result of the “propaganda of fabricated history” by “Koreans.” She called on Japanese residents in Burnaby if they were willing to cooperate, to “get in touch with the Japanese people who are active in Canada.”6

Otaka also mentioned that the Change.org petition and the email templates to Burnaby City were “kindly prepared by Yamamoto Yumiko,” the founder of Nadeshiko Action, not being shy at all about disclosing the fact that the opposition against the statue in Burnaby was initiated and controlled by the right-wing historical revisionists in Japan, not by local residents. On April 1, 2015, Japanese conservative newspaper Sankei Shimbun ran a big front-page story on the Burnaby statue plan in its “History War” series.7 It is remarkable that a national newspaper in a country of over 120 million people saw such newsworthiness in a memorial statue proposed for a city of 220,000, across the Pacific Ocean.

Examples of Vancouver Shinpo running front-page articles on the opposition movement against the Comfort Women statue. Photo by author

By contrast, no Canadian mainstream media took any interest in this except a report or two in Burnaby’s local newspaper Burnaby Now. It reported that on March 18, 2015, about two dozen residents of Japanese ancestry “showed up at the monthly Parks, Recreation and Culture Commission meeting to protest the prospect of a statue commemorating ‘comfort women.’”8 Otherwise, local discussion of the issue was almost exclusively conducted in Japanese, with the weekly Vancouver Shinpo effectively acting as the mouthpiece of the local opposition group called Zo Hantai Kisei Domei Kai [Alliance for Opposing the Statue – hereafter the “Opposition Alliance”],9 led by Gordon Kadota, a Japanese-Canadian businessman.

Nevertheless, there were multiple-level pressures against the statue plan in Burnaby. On the government front, the “Special Committee for Recovering Japan’s Honour and Trust”10 of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party of Japan, led by former Minister of Foreign Affairs Nakasone Hirofumi, on April 2 was briefed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA). MOFA explained that it had been “collecting information since September of 2014, and making proactive, though ‘discreet,’ efforts to stop the erection (of the statue),” such as assisting Burnaby’s Japanese sister city Kushiro’s effort, and working with the Japan-Canada Association and Japanese businesses in Canada.11

Indeed, I learned that opposition meetings were being held at the official residence of the Consul General of Japan in Vancouver, and that Kushiro city was threatening Burnaby city with cancellation of events to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the sister-city relationship. Mayor of Burnaby Derek Corrigan also received direct pressure from Okada Seiji, then Consul General of Japan, and Gordon Kadota, leader of the opposition group who had close ties with the Consul General.12

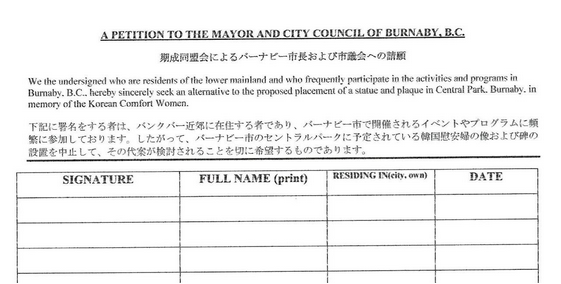

Opposition group Kisei Domei’s petition form. About 1,300 signatures were collected from mid-April to mid-May of 2015.

There were peer pressures as well. Kadota initiated a local petition campaign that collected physical signatures. Petition circulated among local community groups, sports and cultural activities such as marshal arts and tea ceremony, with this kind of pressure: “If you are Japanese, you must sign.” When I met Kadota for the first time on April 10, 2015, he did not hide his surprise that I was not supporting opposition to the statue, being a Japanese-Canadian. Since I was vocal in my criticism of the opposition, soon rumors spread among the Japanese immigrants’ community and among the Internet-right that I was “a Korean (chosen-jin)” and “anti-Japan (han-nichi)”.

However, as Kadota admitted in his Vancouver Shinpo interview on April 9, 2015, participants of the campaign against the Comfort Women statue were almost exclusively “Japanese-Canadians who use Japanese in everyday life, and Japanese-Canadians who use English in everyday life do not even know such a debate is going on.” In fact, quite a few English-speaking Japanese-Canadians reacted differently — while many Japanese-speaking Japanese Canadians regarded the Comfort Women as a defamation of Japan and the Japanese, these second- or third-generation Japanese Canadians saw it as an expression of historical memory that was important to another ethnic group that carries painful war experience. They thought such expression deserved public recognition just as they, Japanese-Canadians who suffered the injustice of war-time incarceration, did when the Canadian government apologized and paid symbolic compensation to the victims and to the Japanese-Canadian community in 1988.

Several second- and third-generation Japanese-Canadians and I drafted an article to inform English-speaking Japanese Canadians about the discussion within the Japanese-speaking community, and submitted it to The Bulletin (Geppo), a monthly journal whose main audience is English-speaking Japanese Canadians. The article was never printed despite our repeated inquiries.

It is estimated that about two-thirds of the citizens of Japanese ancestry in Canada use English as their primary language, and about one-third Japanese. While Gordon Kadota’s Opposition Alliance claimed to represent the majority of Japanese Canadians, the English-speaking Japanese Canadians, who were the majority of the Japanese Canadian community, were hardly given an opportunity to even learn about the debate.

Here is an excerpt from the article that was never published, in which I translated the Opposition Alliance’s rationale for opposing the statue, from the May 7, 2015 edition of Vancouver Shinpo.

- It is quite inappropriate to bring a Comfort Women statue, which contains a sensitive political issue between two countries, to a third country (Canada).

- It is significantly inappropriate to place a controversial statue in a public facility for citizens and immigrants who are adopting multiculturalism and living harmoniously. It will have a major impact on the lives of citizens.

- A Comfort Women statue has already been erected in Glendale, in the United States, and the community has been divided to the extent that it appears irreparable, and bullying of Japanese children has been intensifying. We must never follow in their footsteps.

- There are so many things that we want to say, due to misunderstanding of the facts on the Korean side and differences in historical understanding, but we will refrain from saying them. The reason is that even if we talk about these differences here and now, it is unlikely that any productive discussion will be held, and it will be difficult to achieve our original goal of “not allowing the statue to be erected”.

- The target of our action is the Burnaby City Council: to act so that they will not approve a Comfort Women statue or any statue or monument that resembles such in a public facility.

This excerpt contains the ubiquitously used rationale for Japanese nationalists’ opposition against memorialization of the history of Japanese military sex slavery worldwide, as Tomomi Yamaguchi described, such as the “bullying of Japanese children” in Point 3, for which little evidence has been provided, and history denial in Point 4 as in pointing to the history of Japanese military sex slavery as “misunderstanding of the facts on the Korean side.”

With hundreds of emails, letters, and phone calls and a petition campaign overwhelming Burnaby,13 Mayor Derek Corrigan realized that he was “naïve” about the potential conflict that this issue could entail.14 On April 15, 2015, the day after Gordon Kadota and three other members met the mayor, Corrigan issued a statement that the city would consider a plan that would be mutually agreeable to both Korean- and Japanese- Canadian communities in the region.15 This was interpreted as effective suspension of the plan and Sankei Shimbun reported it on April 18 as a manifestation of “success” of the opposition efforts.16

Given Mayor Corrigan’s statement, the “Peace Statue Committee,” then mostly consisting of Korean-Canadians who wished to build the statue, Gordon Kadota representing the Opposition Alliance, and some Japanese-Canadians who supported the project including myself met on April 27. It was an amicable meeting in which we agreed to work together on the project. After the meeting, however, Kadota insisted on excluding the Japanese-Canadians who were supportive of the statue from the project, resulting in a strong objection from the Peace Statue Committee. Another meeting was planned for May 7, but Kadota cancelled it at the last minute. From that point there was no indication from Kadota or other members of the Opposition Alliance of willingness to work with the Peace Statue Committee.

Over the summer of 2015, the Peace Statue Committee, including not just Korean Canadians but Canadians of various other ethnic backgrounds, including European, Japanese, Filipino, and Chinese, met, and talked about the statue plan, but it never materialized. In the mean time, there was a possibility of placing the statue within the premises of Hannam Market, a Korean supermarket in Burnaby, but the strata council of the shopping complex eventually voted against it. In the end, the statue donated from Hwaseong City found its home on the other side of the continent, at the Korean-Canadian Cultural Association in Toronto and it was unveiled on November 18, 2015.

The Toronto statue was the first Comfort Women statue erected in Canada, and the 3rd in the world outside of Korea, after Glendale, California (July 2013) and Southfield, Michigan (August, 2014). While the Glendale statue was built in a public park, the Southfield statue was built on private property, as the effort to find a public location for it was thwarted by the Japanese government and corporations.

Statue at the Korean Canadian Cultural Association in Toronto, Ontario. Photo by Tomomi Yamaguchi

2015 – 2016: Japanese historical revisionism efforts in Canada

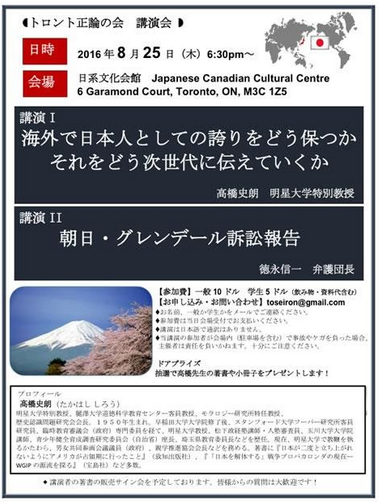

Since around then, Japanese historical revisionists continued their efforts to increase their influence in Canada, as one of the “main battlefields” of their “history wars.” Toronto Seiron no kai, a group of right-wing Japanese Canadians, established in August 2015, has organized talks by right-wing pundits from Japan, such as Takahashi Shiro,17 a conservative education scholar and a key pundit of the Japan Conference (Nippon Kaigi), Tokunaga Shinichi, a lead attorney for the Asahi-Glendale Lawsuit, and Jason Morgan,18 an American instructor at Reitaku University in Chiba, Japan. These talks highlighted denial of Japanese military sex slavery and the Nanjing Massacre.19

Poster for the August 25, 2016 event by the Toronto Seiron no kai, with Takahashi Shiro and Tokunaga Shinichi as guest speakers.

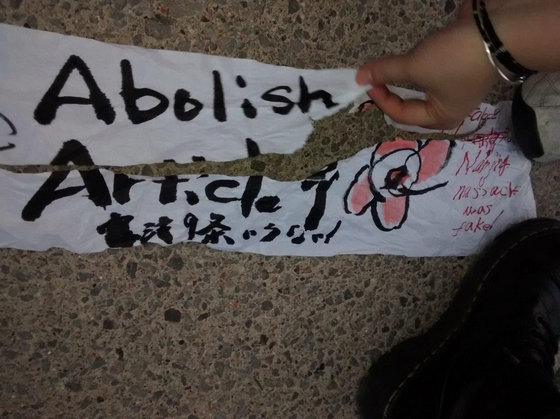

The rightward move in the Japanese-Canadian community in Toronto reached as far as the annual peace event organized by the Hiroshima Nagasaki Day Coalition, a citizens’ peace group in Toronto. On August 6 every year, the group commemorates the history of the atomic-bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki of 1945. Part of the event is the lantern ceremony, in which participants float lanterns with messages for peace, in tribute to the tradition in Hiroshima on the a-bomb memorial day. What surprised members of the Coalition at the 2016 event was that a lantern contributed by one participant said, “Abolish Article 9,” that is, calling for abolition of the war-renunciation clause of the Japanese constitution, and “The Nanjing Massacre was fake!” The Coalition member who found the lantern destroyed it, but took a picture of it for the record.

A history denial message found at the Lantern Ceremony in Toronto, August 6, 2016. Photo provided by Yusuke Tanaka

On November 17, 2016, a right-wing politician Sugita Mio, who became internationally known for her anti-LGBT comment in the August 2018 edition of Shincho 45,20 came to John Junkerman’s screening and director talk of Okinawa: The Afterburn, held at the Downtown campus of Simon Fraser University, which I helped organize.21 Sugita was at that time a freelance writer, between her loss in the December 2014 Lower House election and her comeback in the October 2017 election, engaged with various right-wing historical denial activities.

Sugita’s presence at the Vancouver event only became known when she reported it in her column in the on-line version of Sankei Shimbun weeks later.22 She wrote that she “heard about an anti-Japan meeting in Vancouver” from her supporters living in the region, which was one reason why she came to Vancouver, as well as her interest in the Burnaby comfort women statue debate the previous year. During the film event, she had taken photo shots of myself and another colleague Tatsuo Kage, a respected historian and human-rights activist, and without permission, displayed the photos in her appearance in another well-known right-wing pundit Sakurai Yoshiko’s Internet channel,23 in which she reported what she called “anti-Japan” activities in Canada, including the local Article 9 peace group that Kage and I are part of.

The Simon Fraser University film event Okinawa: The Afterburn with director John Junkerman. Sugita Mio was attending. Photo by author

2016-18: Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day debates

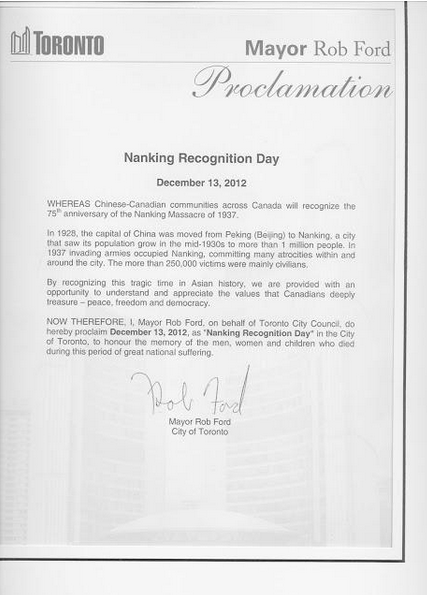

The second major theatre of the Japanese “history wars” in Canada was the contention over moves by some Canadian politicians to establish December 13 as Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day (NMCD), beginning in the province of Ontario, where approximately 14 million, more than a third of Canada’s population, live. In fact, official commemoration of the Nanjing Massacre in Canada was not new. In 2012, Rob Ford, Mayor of Toronto, Ontario’s capital proclaimed December 13 as “Nanking Recognition Day” to mark the 75th anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre, without notable interference from Japanese nationalists or those associated with them.

Proclamation of “Nanking Recognition Day” by Mayor Rob Ford of the city of Toronto, December 13, 2012.

However, when Soo Wong, a member of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario introduced Bill 79 on December 5, 2016 calling for establishment of December 13 as NMCD, negative responses swiftly surfaced, both from the right-wing in Japan but also Japanese-Canadian organizations in Canada such as the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) and the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre (JCCC). As soon as the Parliament of Ontario started deliberating Bill 79,24 David R. Mitsui, President of NAJC published a strong opposition letter to then Ontario’s Premier Kathleen Wynne. Mitsui argued that the Nanjing Massacre dealt with “matters between foreign governments and has nothing to do with” Ontario, and Bill 79 promotes “hostility towards the Japanese Canadian community,” “intolerance,” and will “open the floodgates for others seeking a platform for incidents that occurred outside of this country.”25 The tone and rationale in this letter was similar to those of the Opposition Alliance against the comfort women statue on the West Coast and to similar opposition to memorialization of Japanese military sex slavery around the world, informed and influenced by the Japanese government and Japanese rightists.

Mitsui by this letter meant to represent the NAJC, which he described as the “only organization representing 17 member associations across Canada,” but the Japanese-Canadian community was not so homogeneous as he might have wished. Soon dissent rose from within NAJC, among members of its Young Leaders Committee. In February 2017, the young leaders submitted a letter “Withdraw NAJC Opposition to Bill 79” to the National Executive Board of NAJC, with signatures by 93 Japanese-Canadians.26

The letter states that, “as Japanese, Japanese Canadian, and Nikkei-identified people, we are profoundly disturbed and disappointed by our Association’s strong opposition to Bill 79.” The letter points to the “crucial support that the NAJC received from other groups during the redress movement,” and argues that “the history of redress urgently reminds us, as Japanese Canadians, of our responsibility to join with others in their struggles for justice.”

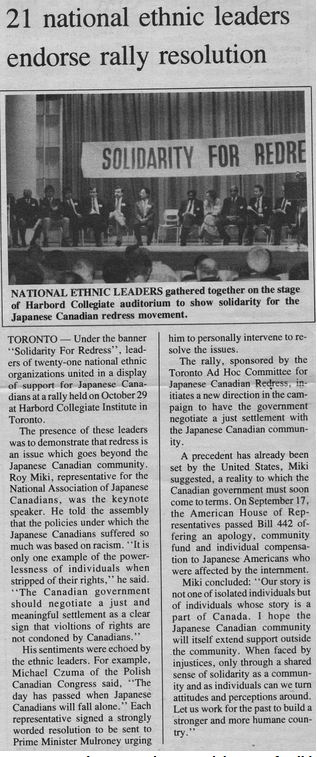

The Japanese-Canadian movement to gain apology and compensation from the Canadian government indeed received support from other ethnic minorities. The December 1987 inaugural issue of Nikkei Voice, a national Japanese-Canadian monthly newspaper reported a rally held in Toronto: “Under the banner ‘Solidarity For Redress’, leaders of twenty-one national ethnic organizations united in display of support for Japanese Canadians at a rally held on October 29 at Harbord Collegiate Institute in Toronto.” According to Yusuke Tanaka, a former editor of Nikkei Voice, this solidarity action added fuel to the last stage of the Redress movement,27 which bore fruit in September 1988, when Prime Minister Brian Mulroney formally apologized to the survivors of the wartime internment and their families, and agreed with Art Miki, then president of the National Association of Japanese Canadians, on the $300 million settlement package.28

From December 1987 inaugural issue of Nikkei Voice (image provided by Yusuke Tanaka)

Poet Roy Miki, Art Miki’s brother and the keynote speaker of the October 1987 rally concluded, “Our story is not one of isolated individuals but of individuals whose story is a part of Canada. I hope the Japanese Canadian community will itself extend support outside the community.” True to his words three decades ago, Roy Miki was among the 93 Japanese Canadians who signed on to the young leaders’ “Withdraw NAJC Opposition to Bill 79” letter, along with Joy Kogawa, another internment survivor known for her literary work,29 and Setsuko Thurlow, a renowned Hiroshima a-bomb survivor and peace activist. But as the campaign progressed, its organizers felt increasing pressure from within the Japanese Canadian community, and eventually had to remove the names of all signatories so that these individuals would not face harassment. NAJC neither responded to this letter, at least publicly, nor retracted their opposition against Bill 79.

Ren Ito, one of the young leaders who initiated this action later launched another letter campaign, “Letter to the Premier: Japanese Canadians for Bill 79,” which collected 100 signatures.30 Author Joy Kogawa was particularly vocal in her support of the NMCD. In September, 2017, she presented 10 reasons why she supported Bill 79 in a Toronto Star article.31 These actions by Japanese Canadians stressed the importance of solidarity with other minority groups in commemoration of their wartime suffering and the importance for Canadians of remembering large-scale atrocities just as they remember the Holocaust.

Opposition to Bill 79 from Japan was also far from absent. In June, 14 Liberal Democratic Party members of the Japanese Parliament sent an opinion statement to the Government of Ontario in opposition to Bill 79, expressing concern for the expected backlash against Japanese and Japanese Canadians if NMCD was established.32 In May 2017, members of the Ontario Legislature received a strange postcard from Japan, which seemed to cast doubt on the number of victims of the Nanjing Massacre.

A post card sent to members of the Ontario Legislative Assembly from an unknown sender in Japan, May 2017. Photo provided by Yusuke Tanaka

Amid such controversy, on October 26, 2017, Soo Wong managed to get unanimous support in the Ontario Legislature for the NMCD, as a motion (Motion 66), not yet as a law. It was reported to be the first parliamentary commemoration of Nanjing Massacre in the West.33 On December 13, members of the Ontario Legislature stood for a moment of silence. Wong re-introduced the NMCD bill in April 2018,34 but the chance to win its approval as a law was lost as she was defeated in the provincial election two months later. Similar moves for legislation of NMCD took place in the provinces of Manitoba and British Columbia, in 2017 and 2018 respectively, but they have not resulted in legislation.

On the federal level, Jenny Kwan, a Member of Parliament from the Vancouver-East riding of British Columbia launched a “Petition to the Government of Canada to Establish Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day” in the spring of 2018.35 I anticipated that the same group of history-denying Japanese nationalists (Kisei Domei) would stage another opposition campaign, so at the end of May 2018, I initiated a new group, Japanese Canadians Supporting Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day.

Website of the Japanese Canadians Supporting Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day

I knew from my own experience that being a Japanese Canadian and supporting such a cause would invite heavy name-calling and Internet-trolling by Japanese nationalists and history deniers, so we ensured the privacy of members. We had near 100 people signed up, from coast to coast, from all walks of life, including teachers, writers, doctors, students, organic farmers, and artists. There were also those who were influential in the Japanese Canadian community, including a former president of the National Association of Japanese Canadians, and author Joy Kogawa, whose newest book Gently To Nagasaki makes referral to the war-time Japanese military atrocities.

Gordon Kadota’s opposition group was not quiet either.36 This time, they created an English name for their group, “Japanese Canadian Coalition for Ethnic Unity,” but the Japanese-language Vancouver Shinpo and its website, were again their major platform. Their opposition reasons were very much the same as before — 1) NMCD will promote hate and intolerance; 2) Do not bring to Canada the one-sided argument about something that happened 80 years ago between Japan and China; 3) NMCD will hurt Canada’s relations with Japan; 4) Do not make Canada an uncomfortable place to live for Japanese Canadians again; 5) NMCD will lead to discrimination and prejudice.37 Somehow, they eliminated a popular rationale, “Japanese children will be bullied,” perhaps because they figured out by then that they could no longer make their case, with little or no evidence to support such a claim.

These pretexts aside, it was evident that one of their primary motives for opposition to the campaign was history denial. On July 11, 2018, the Ethnic Unity group had a large gathering at the Nikkei National Museum & Culture Centre in Burnaby to strategize their opposition against MP Jenny Kwan’s NMCD campaign. There were numerous history denial comments such as “British Columbia’s textbook has a reference to the Nanjing Massacre as a FACT!”, “… I don’t think it happened,” “If historians debated for 80 years and there is no definite evidence, what is the point of arguing the history?”, “Whether Nanjing Massacre happened or not, that’s not the point… the important thing is to quash this bill that Jenny Kwan is trying to present!” It was truly unfortunate that at the Nikkei Centre, a place that carries the memory of WWII Japanese Canadian internment and is supposed to be a symbol of anti-racism and tolerance, such a meeting was held, filled with anti-Chinese hate and historical denialism.

The Racial Unity group argues that the Nanjing Massacre is a foreign incident that happened in a distant past and has nothing to do with Canada. In fact, Canada does remember historical events outside of Canada. One of Vancouver’s public parks, Seaforth Peace Park is home to the late Hiroshima hibakusha Kinuko Laskey’s statue. It is a peace, anti-nuclear symbol and I have yet to hear a single criticism suggesting that it is an Anti-American symbol. There are Holocaust education centres across Canada, and this does not make Canada an uncomfortable place to live in for German Canadians. None of these instigate hate or intolerance; they, instead serve the opposite purpose, to provide Canadians to learn from the painful past in order to create a better future together.

The Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg. Photo by author

At the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg,38 we can study human rights violations in and outside Canada, including the five genocides outside of Canada that have been recognized by the Canadian parliament: Armenian Genocide (1915), Ukrainian Holomodor (1932-33), Nazi Holocaust (1933-45), Rwandan Genocide (1994), and Srebrenica Genocide in Bosnia (1995). The “Breaking the Silence” section that exhibits those histories of genocide states,

“In Canada, people are free to speak openly about human rights abuses. Canadians used this freedom to draw attention to acts of extreme violence and inhumanities around the world. Concerned Canadians have influenced Parliament to recognize five mass atrocities as genocides – deliberate systematic attempts to destroy specific ethnic, racial, religious or national groups. Through such official recognition, Canada speaks out as a nation. It exposes and condemns horrific crimes that have been hidden, minimized, or denied.”

This museum in no way presents Canada as an innocent nation. The “Canadian Journeys,” the largest gallery of the museum presents dozens of Canadian stories of human rights violations, from those of the Aboriginal Peoples (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit), notably the Indian Residential Schools, to those of women, sexual minorities, physically challenged, and racial minorities such as the Head Tax imposition on Chinese Canadians and the war-time incarceration of Japanese Canadians.

The “Canadian Journeys” gallery of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights

With increasing immigration from and trade with Asian nations, it is only natural that Canada considers adding Asian cases to its collective memory of the world genocides.

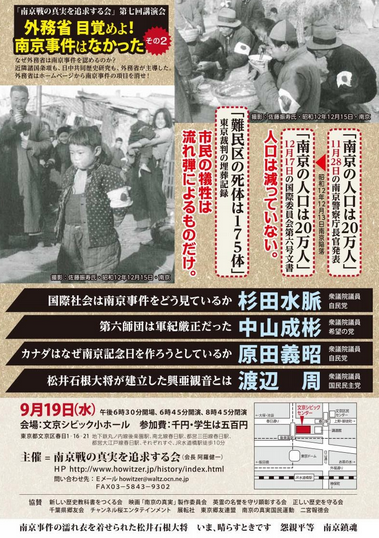

While the Racial Unity members and supporters were writing letters to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and all MPs in opposition to the NMCD, the right wing in Japan was attentive to the possibility of Canada’s federal parliament recognizing the Nanjing Massacre for the first time. On September 19, 2018, a large Nanjing-denier rally “Wake Up Foreign Ministry! Nanjing Incident Did Not Happen” was held in Tokyo. It was the seventh public talk event of the “Group for Pursuing the Truth of the Nanking Battle.” The poster featured four members of Parliament as guest speakers – Sugita Mio (LDP), Nakayama Nariaki (Party of Hope), Harada Yoshiaki (LDP), and Watanabe Shu (Democratic Party for the People).39

Poster for the “Wake Up Foreign Ministry! The Nanking Incident Didn’t Happen” event, September 19, 2018

Where the history of Japanese military sex slavery is concerned, the current Japanese government denies government or military coercion and the notion of sex slavery itself, but where the Nanjing Massacre is concerned, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs states “The Government of Japan believes that it cannot be denied that following the entrance of the Japanese Army into Nanjing in 1937, the killing of a large number of noncombatants, looting and other acts occurred. However, there are numerous theories as to the actual number of victims, and the Government of Japan believes it is difficult to determine which the correct number is.”40

Although this description is far from sufficient, not referring to the large-scale illegal slaughter of Chinese POWs and the rampant rapes of women and girls, and focussing on the uncertainty of the actual number of deaths, the Japanese government does recognize that the Nanjing Massacre occurred. This is the source of the Japanese far-rightists’ frustration with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, feeding the sentiment behind the title of this rally. They want the Ministry to retract its recognition of the history.

Although this was a private group’s event, the fact that three incumbent members of the parliament spoke in support of the cause of the event, including two from the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, is significant. Canada was one of the main concerns of this event. Harada Yoshiaki is a notorious Nanjing denier who publicly called the history a “fabrication.”41 He was one of the LDP politicians who sent the opposition letter to the Ontario Legislature criticizing NMCD. At the rally, he boasted of his efforts such as nudging the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to act, going to Canada himself to lobby, and sending a young scholar to Canada to press the point that the “Nanking Incident didn’t happen.” His handout had a detailed description of NMCD developments in Canada, including background information on Soo Wong and Jenny Kwan. Sugita Mio again singled out my and my colleague’s names to describe “anti-Japan” activities in Canada.

On November 28, 2018, Jenny Kwan held a press conference at the parliamentary press gallery in Ottawa, with author Joy Kogawa, and Tomoe Otsuki who spoke representing the Japanese Canadians Supporting NMCD. Kwan later in the day tabled a motion for NMCD in the Parliament, with the 40,000 signatures supporting her, but it did not gain the unanimous support that it needed to pass. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, in response to Kwan’s call for support, did not clarify his own position on the NMCD, but he acknowledged the need for Canadians to remember the victims of the history.

“Mr. Speaker, of course we deplore the horrific events that took place in Nanjing 80 years ago. All Canadians can agree that the loss of life and violence that so many civilians faced should never be forgotten. We will never forget those terrible acts. The memory of these victims and survivors must be addressed in the true spirit of reconciliation.”42

Although Jenny Kwan’s motion did not pass this time, it was a historic moment in its own right for the prime minister of a third country to recognize the importance of remembering the Nanjing Massacre and its victims.

Notes

In this essay I use the term Japanese Canadians as a broad category that includes all Canadians of Japanese ancestry. “Canadians” here does not necessarily mean holders of Canadian citizenship, but more broadly, citizens or residents of Canada. It is estimated that about two-thirds of Japanese Canadians have English as their primary language and many of the older generation are survivors of the wartime internment and the younger generations are their descendants. The remaining approximately one-third have Japanese as a primary language (though they do use Canada’s official languages in daily life) and they include post-war immigrants, what some call shin-issei, and those who have come to call Canada home after business, work, study, marriage, etc. brought them to the country. The vast majority of local participants of the opposition against the “Comfort Women” statue and the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day belong to the latter category.

“カナダ慰安婦像問題 外務省、昨年9月から情報収集 「設置阻止へ積極的働きかけ」も,” Sankei Shimbun, Aril 2, 2015. https://www.sankei.com/politics/news/150402/plt1504020032-n1.html

“京畿道華城市、カナダ姉妹都市のバーナビー市に慰安婦少女像建立へ,” Hankyoreh Newspaper, March 6, 2015. http://japan.hani.co.kr/arti/politics/19877.html

Mayor Derek Corrigan; Comfort Women, Not a statue of peace, a magnet for conflicts. 慰安婦、平和の像あらず、軋轢を引寄せる磁石 Comfort Women, Not a statue of peace, a magnet for conflicts. カナダBC州バーナビー市慰安婦像設置反対 カナダBC州バーナビー市慰安婦像設置反対,” https://www.change.org/p/comfort-women-not-a-statue-of-peace-a-magnet-for-conflicts-カナダバーナービー市慰安婦像設置反対 This petition page eventually closed with a little over 14,000 signatures.

“【 署名/メール】カナダ バーナビー市 慰安婦像反対!ご協力を!”, Nadeshiko Action, repeatedly updated from March to June, 2015. http://nadesiko-action.org/?page_id=7927

Otaka Miki 【魔都見聞録】カナダ・バーナビー市 慰安婦像反対!ご協力を![桜H27/3/16] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IDoLjkdyT3o&feature=emb_logo

“慰安婦像 カナダで提案 韓国の姉妹都市 邦人ら反対運動,” Sankei Shimbun, April 1, 2015. https://www.sankei.com/world/news/150402/wor1504020004-n1.html

“Comfort women statue proposal riles group of Japanese Canadians in Burnaby,” Burnaby Now, March 19, 2015. https://www.burnabynow.com/news/comfort-women-statue-proposal-riles-group-of-japanese-canadians-in-burnaby-1.1798189

The full name of the group is 「バーナビー市慰安婦像設置反対期成同盟会」.

It is unknown whether any official English name for the group exists. A literal translation of the group name is the “Alliance Group Established for the Purpose of Opposing the Erection of a Comfort Women Statue in Burnaby City.”

“日本の名誉と信頼を回復するための提言,” The Liberal Democratic Party of Japan, July 28, 2015. https://www.jimin.jp/news/policy/128434.html

“カナダ慰安婦像問題 外務省、昨年9月から情報収集 「設置阻止へ積極的働きかけ」も,” Sankei Shimbun, April 2, 2015. https://www.sankei.com/politics/news/150402/plt1504020032-n1.html

As Tomomi Yamaguchi describes in her paper, Japanese American veteran Robert Wada wrote a letter of opposition to Mayor Derek Corrigan of Burnaby City. Wada’s letter also circulated among the Japanese Canadian community.

“バーナビー市長に聞く 慰安婦像建立は未定,” Vancouver Shinpo website (date unknown)http://www.v-shinpo.com/local/1488-110-16247615

“慰安婦像設置は「当面保留」 カナダ西部バーナビー市 日系住民の反対奏功,” Sankei Shimbun, April 18, 2015. https://www.sankei.com/world/news/150418/wor1504180012-n1.html

Japan-U.S. Feminist Network for Decolonization is a useful English-language guide to Japanese history revisionists’ activities in the United States and beyond. Its Encyclopedia has an entry on “SHIRO TAKAHASHI”(http://fendnow.org/encyclopedia/shiro-takahashi/) and “TORONTO SEIRON” (http://fendnow.org/encyclopedia/toronto-seiron/).

“JASON MORGAN,” Encyclopedia, Japan-U.S. Feminist Network for Decolonization. http://fendnow.org/encyclopedia/jason-morgan/

These talks are available on the Toronto Seiron YouTube channel. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC4x4kumw2UcmYjiTOwZ0OkA

For details about the controversy, see, for example, “Japanese magazine to close after Abe ally’s ‘homophobic’ article,” The Guardian, September 28, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/26/shincho-45-japan-magazine-homophobia-mio-sugita-shinzo-abe

Film screening and director talk by John Junkerman, Okinawa: The Afterburn, sponsored by Simon Fraser University’s Institute for Transpacific Cultural Research, VanCity Office of Community Engagement and the School of Communication along with the Peace Philosophy Centre, November 17, 2016, at Simon Fraser University Downtown Campus. http://www.sfu.ca/itcr/events/past-events/okinawa-afterburn.html

“杉田水脈のなでしこレポート(23)沖縄の基地反対運動を美化したドキュメンタリー映画…私には見るにたえない作品でした,” Sankei News, December 18, 2016. https://www.sankei.com/premium/news/161218/prm1612180015-n1.html

“歴史戦は政治が動かなければ勝てない オンタリオ州議会が南京大虐殺記念日制定へ,” Genron Terebi, February 10, 2017. https://www.genron.tv/ch/sakura-live/archives/live?id=367

“Bill 79, Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day Act, 2016,” Legislative Assembly of Ontario. https://www.ola.org/en/legislative-business/bills/parliament-41/session-2/bill-79

David R. Mitsui, “Bill 79 Day to Commemorate the Nanjing Massacre,” National Association of Japanese Canadians, December 7, 2016. http://najc.ca/bill-79-day-to-commemorate-the-nanjing-massacre/

“Withdraw NAJC Opposition to Bill 79,” https://docs.google.com/document/d/1v4ecwv3jdaKAUwn_aZqXwIka4in0upn060nwPNg5Lgo/pub

Yusuke Tanaka 田中裕介, “日系人の試練の日々の恩人たちに感謝を捧げる集い,”article series 滄海一粟Sokai no ichizoku, The Bulletin月報, February 2020, P44.

1988: Government apologizes to Japanese Canadians, CBC Digital Archives. https://www.cbc.ca/archives/entry/1988-government-apologizes-to-japanese-canadians

“Criticism from within Japanese Canadian communities against Japanese Canadian groups’ opposition to Ontario’s Bill 79, An Act to Proclaim the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day,” Peace Philosophy Centre, https://peacephilosophy.blogspot.com/2017/02/japanese-canadians-oppose-japanese.html

“Letter to the Premier: Japanese Canadians for Bill 79” https://docs.google.com/document/d/1xvuNylgt_HxDkZLjqUx1WeF_3SzaQFAQ6Ih2rSsEdcc/pub

Joy Kogawa, “Why I Support the Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day Act,” The Star, September 15, 2017. https://www.thestar.com/opinion/commentary/2017/09/15/why-i-support-the-nanjing-massacre-commemorative-day-act-joy-kogawa.html

“南京大虐殺巡りカナダ州議会に意見書 自民有志14人,” Nikkei Shimbun, August 20, 2017. https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXLASFS20H15_Q7A820C1000000/

“MPPs unanimously pass motion to commemorate victims of Nanjing massacre,” The Toronto Star, October 27, 2017. https://www.thestar.com/news/queenspark/2017/10/27/mpps-unanimously-pass-motion-to-commemorate-victims-of-nanjing-massacre.html

“Canada’s Ontario legislature passes motion on Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day,” New China, October 27, 2017. http://www.xinhuanet.com//english/2017-10/27/c_136708560.htm

Nanjing Massacre day bill reintroduced,” China Daily, April 14, 2018. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201804/14/WS5ad121fea3105cdcf65183d7.html

“Petition to the Government of Canada to Establish Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day,” Jenny Kwan, MP. https://www.jennykwanndp.ca/recognize_nanjing_massacre_commemorative_day

Vancouver Shinpo had a special page dedicated to opposition against Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day. “「南京虐殺記念日」制定反対特設ページ,” Vancouver Shinpo. http://www.v-shinpo.com/local/5087-tokusetsu-kinenbihantai

“「南京大虐殺記念日」制定運動始まる メトロバンクーバー日系社会に衝撃,” Vancouver Shinpo, May 24, 2018. http://www.v-shinpo.com/local/5058-local180524-1

See “Galleries” page of the Canadian Museums for Human Rights website. https://humanrights.ca/exhibition/galleries

Japanese weekly Shukan Kinyobi reported this rally. “「南京大虐殺否定集会」に杉田水脈氏ら登壇,” Shukan Kinyobi, October 26, 2018.

“Q6: What is the view of the Government of Japan on the incident known as the ‘Nanjing Incident’?”, History Issues Q & A, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, April 6, 2018. https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/q_a/faq16.html

For example, Ogiue Chiki’s interview with Harada Yoshiaki, TBS Radio, October 19, 2015. https://www.tbsradio.jp/298756

42nd Parliament, 1st Session, Edited Hansard, Number 360, House of Commons, November 28, 2018. https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/house/sitting-360/hansard