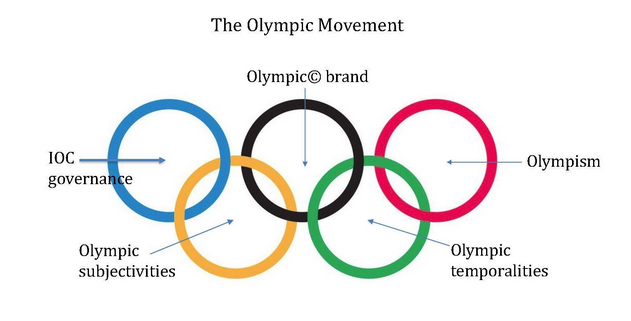

Abstract: The Summer Olympic Games is the most watched sports mega-event in the world. It is also the costliest, the most politically precarious, and the most strangely constructed sports mega-event on the planet. At the 2020 Games in Tokyo, athletes and spectators alike will be focused on the elite bodies in motion, in agonistic contests and aesthetic displays of excellence and effort. Behind the scenes, however, is a less apparent but deeply powerful institutional and ideological apparatus—the Olympic Movement—that sets the stage, establishes the rules, and reaps many of the benefits of this quadrennial spectacle. My essay offers an anatomy of the Olympic Movement (OM) through the five ways in which it has come to dominate global sport: through the International Olympic Committee as the apex of a transnational governance structure; through the OM management of the Olympic brand as the most lucrative in global sports; through Olympism as the OM’s philosophy of universal sports humanism; through OM’s power to define and defend multiple subjectivities—Olympic sports, Olympic genders, Olympic citizens, and Olympic bodies; and through the ability of the OM to orchestrate the rhythms of global sport through Olympic temporal regimes. It would appear from these powers that the OM is unassailable and unaccountable, yet the essay concludes by arguing that the OM is an example (perhaps a rare example) of how powerful interests can be made vulnerable to what we can call “rhetorical self-entrapment” and the revenge of unintended effects.

The Summer Olympic Games and the FIFA World Cup for men’s soccer are the most watched sports mega-events in the world, and their television audiences and other media attention dwarf even other mega-events like Tour de France, World Cricket Championships, and Super Bowl. The Olympic Games and the World Cup have two features in common: they both occur every four years and they are both run by vast transnational self-governance structures, with lofty sporting ideals but opaque, oligarchic procedures, tinged with corruption. Otherwise, however, they are a very odd pair.

The Soccer World Cup showcases a single team sport, which not coincidentally is the most popular in the world, played and watched by literally billions of enthusiastic and knowledgeable participants and spectators. The quadrennial World Cup has a country sponsor (it will be Qatar in 2022), with run-up games among 32 qualifying national teams (totaling some 850 players), distributed for three weeks across multiple cities and stadiums.

The Summer Olympic Games, by contrast, is hosted every four years by a single city, not its country, and it is the only mega-event in the world that brings together multiple sports, male and female athletes, and (through the Paralympic Games that follow immediately), abled and disabled athletes. The 2020 Summer Olympics will feature 339 separate events in 33 different sports, drawing over 11,000 athletes from 206 National Olympic Committees packed into a 17-day schedule. The scale of these Olympics is just that, Olympian: housing and transporting tens of thousands of athletes, media, and visitors around a single city, the many different venues required, the complex logistics of 33 different types of sporting competitions. The demands of planning and executing and financing vastly exceed even that of FIFA’s World Cup.

And, unlike soccer, the world’s game, whose rules and teams and players are known intimately by billions of fans, it is equally remarkable of the Olympic Games that almost all of its 33 sports have very little following in the world (Slalom canoeing? Madison cycling? Greco-Roman wrestling?). Most of us watching, regular sports fans or not, have little or no knowledge of the sports—the rules, the techniques, the athletes, the scoring, the stakes involved. At best we see them once every four years. There may be a certain pleasure in watching such an unfamiliar diversity of trained bodies in competitive motion over such a range of venues from hockey fields to swimming pools to dressage rings to running tracks and much more. But this is a most unlikely format to produce the world’s most watched sports gathering.

So the Olympic Games are not only compelling for this array of sports and the 11,000 athletes who compete. It is even more fascinating to contemplate just how it is that those who produce and broadcast the Olympics can possibly generate enough knowledge and passion in billions of potential viewers to actually get us to watch and care and justify the billions of dollars spent on producing them. Much of the attention is understandably focused on Tokyo, its Organizing Committee, and the national government—and the concerns and controversies generated by this undertaking to host the Games.

But behind the maneuvering and preparations in Tokyo lies a far broader Olympic Movement, largely unseen and little appreciated by the Summer Olympics audience, and yet that is the institutional and ideological apparatus that sets the stage, establishes the rules, and reaps many of the benefits of this quadrennial spectacle.1

It is this Olympic Movement that is the focus of this essay, the substance of which is to characterize its five key elements. After outlining each of these elements, I conclude by considering the effects of such a ramifying apparatus, seemingly so dominant and unassailable in shaping global sports. In fact, the essay argues that the Olympic Movement’s hold on global sport is more tenuous. It is an example (perhaps a rare example) of how powerful interests can be made vulnerable to what we can call “rhetorical self-entrapment” and the revenge of unintended effects.

1. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) as Transnational Governance

Controlling the Olympic Movement (OM) and orchestrating the Games is a transnational governance structure, at the apex of which is the International Olympic Committee (IOC). The name is a quaint and deceptive anachronism. The modern Olympics was the brainchild of a French educator, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, who brought together a committee of 16 men in 1894 to plan an international competition roughly modelled on the classical Games (MacAloon 2006). But 125 years later, from its headquarters in Lausanne, Switzerland, the IOC is a structure of sovereign governance on a global scale and density and a concentration of claims, powers, and resources unmatched in the sports world

It was far from certain in its early days that the IOC would survive let alone grow to such dominance. The inaugural Games it staged in Athens in 1896 drew 245 male amateur athletes, overseen by 15 members of the IOC. The games that followed (1900 Paris, 1904 St. Louis, and 1908 London) were held in conjunction with and not infrequently lost within international expositions. The 1912 Games in Stockholm (at which Japan debuted as the first Asian nation) were held on their own, but the IOC was concerned that host cities were gaining too much latitude in running the Games, picking the sports, and choreographing the contests, so it moved to assume direct control over all elements of the Games, powers that it was never to relinquish. De Coubertin used his hand-picked committee to contain the leading international sports federations, especially the International Amateur Athletics Federation, and then, in the 1920s, his IOC co-opted or strangled several rival Games, especially the upstart Women’s Games and the Worker Games.2

Baron Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Movement

Source: IOC

Meeting of the IOC at the inaugural 1896 Athens Olympics (Coubertin is second from the left).

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The IOC itself is neither representative nor transparent. It has had only nine presidents in its 125-year history. The president, with four vice-presidents, controls the executive board and the 115-member Committee. Committee members are self-selected and self-perpetuating, and only recently has it broadened its membership beyond a narrow range (Chappelet and Bayle 2016). Despite its name, the IOC is not international governance because its constituent units are not nations; it is not like the United Nations or the World Bank. Instead, the unit members are National Olympic Committees, each of which manages Olympic-related affairs for usually but not necessarily a nation-state (like the USA), but sometimes nation-states with partial and contentious recognition (such as “Chinese Taipei” and “Hong Kong, China”), and territories within nation-states (Guam, American Samoa, the Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico have separate National Olympic Committees, as does Palestine).3 The IOC makes its own diplomatic distinctions, which has periodically embroiled it in highly contentious political struggles.

The IOC—especially its executive board and its staff—coordinate the rights and responsibilities of six types of subordinate and ancillary organizations and institutions:

- The IOC authorizes and provides guidelines and some financial support to the above National Olympic Committees (currently, there are 206 official NOCs).

- The IOC coordinates with the international sport federations of all of the sports represented in the Olympics and Paralympics; these are governing bodies of individual sports, such as World Athletics, the International Swimming Federation, the International Cricket Council, etc. Except for major federations like World Athletics and FIFA, most (73 at present) are largely subordinate to the stipulations of the IOC.

- The IOC also appoints and directs some 30 staffed Commissions, charged with administering and advising some aspect of IOC work, such as the Ethics Commission, the Athletes’ Commission, the Sustainability and Legacy Commission, etc. There are currently 30 such bodies.

- The Olympic Museum, the International Olympic Academy, the Olympic Studies Centre, and other cultural/educational institutions are operated for disseminating Olympism and running cultural programs around the world.

- The two most important judicial adjuncts to IOC sports sovereignty are the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) and the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). The CAS was set up by the IOC in the early 1980s, and while its budget is now separate from the IOC, the IOC mandates that all Olympic-related disputes must go to the CAS for resolution. WADA was organized by the IOC as a legal foundation in 1999, and its Board membership is split between IOC appointments and national government representatives. It writes and applies the World Anti-Doping Code, and, in circular reinforcement, mandates the Court of Arbitration for Sports as the ultimate jurisdiction in deciding all sports doping-related cases (for example, the ongoing cases of massive Russian doping of its athletes up to the Sochi Winter Olympics have proceeded through these two institutions).

- The Host City Organizing Committees for the ongoing Olympic Games, the entities with which the IOC enters into a formal “host city contract” to stage each Games

Thus even among international and transnational governmental and non-governmental organizations, the IOC in coordinating the Olympic Movement has extraordinary reach, unusual powers, and a deep history.

New headquarters of the IOC that opened in 2019 in Lausanne, Switzerland, adjacent to the villa (at left) that had long housed its offices.

2. The Olympic© Brand as Revenue Source

As the IOC grew through the twentieth century to consolidate its control over global sports organizations and calendars, it was becoming a transnational economic behemoth as well, with a current cash surplus of over USD 1 billion. Using its management of the Summer Games as a singular sports mega-event, the IOC developed the Olympics into one of the most lucrative brands in global sports, perhaps second only to the corporate Nike brand. Again this was not inevitable, and in fact its economic power lagged historically behind its growing political influence.

It was only in the 1960s, through and after the Tokyo 1964 Summer Olympics, with new broadcast and transmission technologies and with booming television ownership in Europe, North America, and Japan that the IOC recognized the potential for sizeable broadcast licensing fees. It was not until 1984, when the Los Angeles Summer Olympics was the first to demonstrate how corporate sponsorship could be mobilized to generate a significantly new revenue stream for the IOC and the host city alike.

These two revenue streams remain today the most lucrative sources for the IOC (by comparison, on-site revenues from Games attendance themselves yield little). The Olympics brand has become one of the most lucrative and desirable sponsorship associations in all sports, and the IOC jealously protects and aggressively markets what it presents as the “Olympic Properties.”4

Its Worldwide Olympic Partner Program (TOP) is the top tier of 14 global corporations, each of which pay around USD 100 million to be an official sponsor and supplier (six of these are East Asian-based multinationals and eight are Euro-American-based). In addition, the Organizing Committee for each Games can recruit three lower tiers of official Games sponsors for its own revenue; for 2020, Tokyo has lined up 67 such sponsors. All in all, total sponsorship and advertising revenue for 2020 Games should easily exceed USD 2 billion.

The monopolistic broadcast rights for all Olympic-related broadcasting is even more profitable for the IOC. Beginning in 2001, the IOC established its own Olympic Broadcasting Services, to produce and deliver all footage from all venues during the Games and to operate the on-site International Broadcast Center for all print and digital media). This master feed is distributed to all broadcast organizations that have purchased television and radio rights from the IOC. They are known as Rights Holder Broadcasters (RHB), presently numbering 200, and total media rights will yield the IOC over USD 3 billion for the upcoming Summer Games. Most RHB serve single countries, and a few control world regions. Japan rights have been bought by a consortium of NHK and commercial broadcasters, while the Japanese ad agency Dentsū is RHB for 22 countries in East and Southeast Asia, subleasing its feed to country networks.

The consequences of this streaming structure are profound. For the duration of the Games, there is a continuous, single, multi-channel master feed emanating from OBS to all RHB networks, but each of these national networks is then free to edit the master feed to create its own Olympic broadcasts. In that sense, there is no 2020 Summer Olympics Games but rather there are over a hundred national editions of the “same” Summer Olympics, a polyglot glocalization of imagery and commentary.

To the occasional spectator, it may seem odd to write of profits and surpluses, but there is a crucial distinction between the cost burdens and revenue streams for the IOC and the particular host city for each Games. The burdens of inflated operating budgets and huge lingering deficits is a common fate of the local host city, its nation, local sponsors, and taxpayers. One of the most important clauses in the IOC host city contract indemnifies the IOC from all losses (IOC-TCOCG 2013: 13-14)!

3. Olympism as a Philosophy of Universal Sports Humanism

Many sports like to surround their training and competition with pieties about character-building and life lessons—college football here in the US is a prime example—but the Olympic Movement has, far and away, gone the furthest in justifying its sport mission and grounding its Games in a total philosophy of life. There is no basketball-ism or kayak-ism, but there is an elaborately articulated Olympism, whose “fundamental principles” appear in the IOC Olympic Charter (2019:11), most succinctly in the claim that:

“Olympism is a philosophy of life, exalting and combining in a balanced whole the qualities of body, will, and mind. Blending sport with culture and education, Olympism seeks to create a way of life based on the joy found in effort, the educational value of good example and respect for universal fundamental ethical principles.”

Unlike its exponential organizational growth during the 20th century, Olympism’s ambitions as a universal sports humanism has been the guiding ethos since Coubertin’s original 1890s vision (DaCosta 2006, McFee 2012). He was addressing a small, elite population—white, Euro-American males of enough means to play the amateur sports of the day—but he was fervent in his belief in the intrinsic power of sports, properly managed, to foster healthy bodies and minds, ethical social relations, and peace and comity among nations. In the ensuing century, the OM has become ever more expansive in the ethical imperatives of its sports, even as it consistently falls short of realizing them. By the second half of the twentieth century, the Charter’s Sixth Principle of the Charter proclaimed unequivocally that “the enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in this Olympic Charter shall be secured without discrimination of any kind, such as race, color, sex, sexual orientation, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.” The OM mandate has expanded even wider in the present century, with demands on host cities to produce Games that are both economically and environmentally sustainable. This is a huge social and ethical agenda for sports to bear.

This ideology of Olympism is not only expressed through lofty rhetoric but dramatized in symbol and ceremony. In the Committee’s very first year, 1894, Coubertin coined what became the Olympic motto, Citius, Altus, Fortius (“Faster, Higher, Stronger”), which he introduced at the first Olympics in Athens 2 years later. He wanted to complement the phrase with a logo design and several years later produced what is by far the most ubiquitous Olympic symbol, the five interlocking rings (several interpretations have been offered for this, one of which is the rings represent the five continents, each distinctively colored but linked through the OM). Then for the 1912, he fashioned an Olympic flag to better display the five-ring logo.

Olympic Charter, 2019

Source: IOC

An Olympic flame, presiding over the central stadium was introduced for the 1928 Amsterdam Games, and as part of his grandiose scheme for the 1936 Berlin Olympics, Hitler persuaded the IOC to authorize an extension of this ritual. A torch was lit by the sun’s rays on Mount Olympus, and a relay of “sacred runners” carrier the torch all the way up to Berlin to light the stadium flame. There was a steady accretion of ceremony. An Olympic anthem was written, athletes took an Olympic oath, an Olympic creed reinforced the motto, medal award ceremonies featured olive branch crowns, national flags and anthems, and the medallions themselves, and posters and emblems were designed by the host city Organizing Committee to commemorate and signify each Games. The pageantry became ever more choreographed, with an Opening Ceremony and a Closing Ceremony bookending each Games. These are the signature events to showcase the host city and its nation, ever more elaborate and expensive. Programs in Olympics arts and cultural education run during the Games (and throughout the year in Lausanne and elsewhere).

In sum, there are symbolic redundancies to Olympism to fill every visual nook and aural cranny of the Games (as well as the sponsors’ products). Olympism is thus not just the pronouncements of ideals and the display of associated symbols and logos, but it is conveyed through the large-scale ritual enactment of ceremonies and programs that sustain a totalizing ideological force field.

This of course is Ritual 101 for an anthropologist: take a sanctimonious message and wrap it in as many media forms and layers as possible to render it edifying, entertaining, and efficacious. But it is also key to the popularity of the Games as sports as well. Because almost all Olympic sports have only narrow audiences, they must be presented as stories and characters and personalities set against a tapestry of ceremony and symbolism. The Olympics, then, celebrate sport in a generalized rather than specific sense, and its ceremonial apparatus becomes integral to this, enfolding the athletes and ennobling the competitions.

4. Olympic Subjectivities

At the Opening Ceremony on July 24, the 11,000 participating athletes will parade into the national Olympic stadium in smartly-uniformed formation behind national placards and flags in an order determined by IOC protocols for an extended ceremony of proclamations, oaths, and garish multi-media displays, organized by the Tokyo Organizing Committee, again following IOC guidelines. The scene of the assembled athletes looks highly choreographed, which indeed it is, and to the ordinary viewer, fully naturalized, which it decidedly is not. Who are these athletes and how did they come to be in the formations on our screen?

This is a matter of subjectivity, and along with the organizational dominance, financial clout, and ideological claims, a fourth key feature of the Olympic Movement is its power to define the subjectivities of the global sports formation. This is manifest in at least four major realms.

Olympic Sports

The sports that appear in the Olympic Games have grown in number over its history and there have been some replacements, although there has been surprisingly little change in recent decades. For the 2020 Summer Games, baseball/softball returns (after being dropped from the 2012 Games) and for the first time, skateboarding, surfing, karate, and sports climbing have been added, presumably to enhance the Games’ appeal to younger viewers.5

The 33 sports at the 2020 Summer Games

Source: Tokyo 2020 Guidebook, Pages 4-5

Competition for designation is fierce, and the IOC has set out an exhaustive assessment process by an IOC select committee, which grades proposals on 39 criteria in 8 categories to determine worthy Olympic sports.6 Sport is hardly an obvious category but rather is highly arbitrary, contextual, and contingent. The IOC has the power not only to select but also in a substantive way to shape these sports, and through that, to determine what counts as organized competitive sport in the contemporary world. There are many niche sports that lack any Olympic ambitions (and a few major ones, like American football), but for many, Olympic designation is the key to popularity and financial survival. It is the possibility of IOC stipulation and the allure of the Olympic imprimatur that leads so many sporting activities in the world to assume an increasingly uniform structure of rules, competitive formats, administrative organs, and scheduling.

Olympic Citizens

The OM’s relationship to the modern world order of nation-states and nationalism has been both complex and contentious from the start. Coubertin initially saw participating athletes as individuals, but that changed quickly with the third Games in 1904, when the IOC defined athlete participation in terms of national belonging rather than as unaffiliated individuals, even while refusing to organize its own administration by nation-state representation. The ambiguity continues to the present; as noted above, at Tokyo 2020, 206 National Olympic Committees will send contingents, usually though not always corresponding to a nation-state, with its flag and anthem.

One consequence has been that Olympic citizenship, which is to say, one’s membership on a NOC team entry, is adjudicated by IOC protocols, rather than the nation-state (Jansen et al 2018, Schachar 2011), and this has led to an increasing amount of nationality shopping, by athletes and countries. The Olympic Charter (Article 41) requires only that an athlete be a national of the country (NOC) for which he or she is competing. To compete for a different NOC, they are supposed to wait three years after last competing for their country of origin, but the IOC will waive this if the athlete has permission from their original NOC and the relevant athletic federation, which is not infrequent. Changing Olympic nationalities is not difficult for a talented athlete. At the Games, IOC Olympic citizenship trumps nation-state citizenship, and nationality becomes something of a free-floating signifier (Carter 2012).

This has been criticized as commercializing and cheapening state citizenship with a flood of mercenaries. For instance, Great Britain, eager to do well at its 2012 London Olympics, had 60 foreign-born and newly-minted citizen-athletes, whom the British press were quick to dub “Plastic Brits.” We should not be entirely dismissive. Japan, too, has used expedited naturalization to attract foreign athletes (in soccer and rugby sevens as well as certain Olympic events; Kelly 2013a), and their prominence and sport success, along with Japanese citizens of international marriages (Schanen 2016) have had a considerable demonstration effect on prospects for a more multi-cultural view of Japanese citizenship.

Olympic Genders

There are two Olympic genders, male and female.7 Apart from a few exceptions (some pro tennis, ice skating, and track/field championships), the Olympics are highly unusual not only in being multi-sport but also for jointly showcasing male and female sports—actually, male and female versions of the same sports, side-by-side, with increasingly equal exposure and rules and equitable medaling. (FIFA, by contrast, mounts entirely separate and vastly unequally supported Men’s and Women’s World Cups.)

At the outset, there was one Olympic gender, the male (or more precisely, the white Euro-American male amateur). Coubertin and the early IOC as figures of their era saw sport as the preserve of the male body. The promotion of women’s participation in the Games has not been easy—and took most of the twentieth century. Even at the 1964 Tokyo Games, female athletes numbered only 678 (13%) of the 5151 athletes, but the 2020 Games are on target to reach 50%-50%. Despite this long history of struggle, it is fair to say that the OM has probably been the single most important factor in the growth of women’s sports participation. The U.S has had Title IX, since the early 1970s. The rest of the world has the Olympics (for Japan, see Kietlinski 2011, Kelly 2013b). Japan has been one of the countries that recognized the prestige value of Olympic excellence early on, and has been long aware of the value of encouraging female elite athletes in a wide range of Olympic sports. Indeed, with few opportunities for professional sports careers, elite women athletes are often drawn into sports that lead to Olympic recognition. Kinue Hitomi was the sole female in Japan’s 43-member delegation in 1928, winning the first Olympic medal by a Japan female athlete, a silver medal in the 800 meters run; by 1964, the 61 female athletes constituted 21% of Japan’s delegation, and by the 2004 Athens Games, Japanese female athletes outnumbered their male counterparts 171–141. The list of female medalists, the media attention they receive in Japan and their subsequent careers are testimony to this positive impact on gender equality.

At the same time, the entry and growing importance of female athletes has forced the IOC to step into the fraught issue of just who is a female athlete and who is a male athlete, and a series of high profile cases from the 1950s to the present year has failed to resolve the question (Kerr and Obel 2018, Pieper 2016, Sailors 2016). Rather, in fact, the Olympic gender binary remains a tenuous and contested distinction, increasingly implausible and indefensible but for the moment, still sovereign in sorting Olympic sports and their athletes.

Olympic Bodies

Implicit in the search for rules of fair play that enables the equitable competition at the heart of the Games and its sports is some notion of the sporting body—the “natural” body as distinct from its “unnatural” enhancements, be they material, technological, surgical, pharmacological, or something else. Deciding what may be done to sporting bodies and what sporting bodies may use has been a continuing question whose resolution is constantly challenged by new material and medical technologies. The IOC has long been at the center of such decisions for the full range of sports, working through the international sport federations and, more recently, through its Court of Arbitration for Sport and World Anti-Doping Agency. It renders decisions about therapies and drugs that repair injured bodies versus those that enhance bodies, about equipment and materials that create unfair competitive advantage (swim suits, rowing sculls, rifle sights, running shoes, etc.), and about classifications of bodies that create classes of competition (as in boxing and wrestling weight levels). Many of the decisions about the permitted and banned Olympic body are arbitrary: Why are cross-country ski teams allowed to train with high-tech oxygen tents to expand oxygen capacity but they are banned from using EPO blood doping to achieve the same effect of increasing red blood cell count? This distinction is all the more difficult when we consider that only well-supported national teams can afford oxygen tent and other high tech training methods, while EPO blood “doping” is an accepted and necessary hospital treatment for patients with chronic high anemia.

With the increasingly close pairing of the Olympics and the Paralympics, the IOC has created yet another distinction to determine and defend, that between the Olympic body versus the Paralympic body; the most celebrated case thus far was that of the South African runner (and, subsequently, convicted murderer) Oscar Pistorius, a double-leg amputee who competed in both the Paralympic and Olympic Games. In the 2020 Games, Japanese sprinter Itani Shunsuke will compete in the Paralympics, but could also have attempted to qualify for the Japanese Olympic team as well. Such possibilities not only animate media commentary and the online posts of fans around the world but also fill the pages of such scholarly journals as Sport, Ethics and Philosophy and the Journal of the Philosophy of Sport!

The 22 sports at the 2020 Paralympic Games

Source: Tokyo 2020 Guidebook, Pages 6-7

5. Olympic Time as a Temporal Regime

The Summer Olympics is a periodic blip in the global calendar, appearing on our screens every four years, holding our attention for a few weeks, and then quickly receding from our daily concerns. During the run-up, there are occasional controversies that break through the news cycle, such as the plagiarism of the initial Tokyo Olympics logo and the ruckus over the National Stadium design, but even these give us no sense of just how intricate and continuous are the Olympic temporal rhythms that schedule not only the Games themselves but much of the global sports calendar.

Olympic temporality is composed of extended, overlapping, and interpenetrating cycles centered on the Games, each of which passes through a long, four-stage chronology before and after the event itself. First, a Games has a pre-history that begins 15 years or so before the Opening Ceremony, as a city mobilizes municipal support from business interests and residents, competes with other cities within that country to move ahead, and then mounts a long bidding campaign with the IOC for “applicant city” status; if successful, it moves to “candidate city” standing, which requires preparing a detailed Games infrastructure plan and budget along strict IOC guidelines and demonstrating sufficient local political, economic, and civic support. The “host city” is selected among the candidates after multiple IOC site visits.

In this sense, the 2020 Olympics began in Japan back in 2004, when then Tokyo Metropolitan Governor Ishihara, mindful of Beijing’s upcoming 2008 Games and ignoring civic skepticism and opposition, set the city’s sights on the 2016 Summer Games. He pushed Tokyo to applicant city status and then to candidate city designation, but the city lost to Rio in 2009. Undaunted, he immediately began revising the bid for 2020, advancing to candidate city status in 2011, and finally being successful in 2013. This initiated a second stage, the ongoing, extended run-up to the Games itself, during which the host city and its country undertake massive and intensive infrastructure construction, broadcasting and other commercial rights and forms are negotiated, an aesthetic design thematic of the Games is created and promoted in multiple media and products, Olympic educational programs are launched, and so on.

IOC Guidelines for Candidate City Application

Source: IOC

The Games themselves are thus a brief frenetic moment in this long temporal sequence, a concentrated burst whose very compression gives energy and significance to the mega-event. But even as the flame is extinguished, a fourth and often longest stage of the Games’ cycle begins, its aftermath. There are requirements to be met, in completing and publishing official and unofficial records of the Games (statistics, reports, documentaries, etc.), but the culminating project is the fashioning and burnishing of public memories of the Games. The OM has adopted “legacy” as its official term for such memory work, but the long endgame of a Games is a clash of competing accounts, sanctioned and unsanctioned, as the Games are fit into local contentions and a global Olympics history (e. g., Holt and Ruta 2015). As other papers in this Special Issue have documented, the legacies of Tokyo’s two previous Summer Games—the “phantom” 1940s Games and the 1964 Games—are still actively shaping the planning for and the discourse about the upcoming Games.

Thus, the Games cycle moves from mobilization and bidding process, to the long preparatory run-up, the Games themselves, and the long tail of legacy—each of which is filled with contestation, suspense, and expense. This is of course a generic chronology, and the rhythm, intensity, content, and historical longevity of each Games has varied significantly.

An important effect of this extended timeline is to create multiple overlapping Games cycles that mutually condition one another. Tokyo’s bid for the 2016 Games and then the 2020 Games not only addressed and built upon its previous Games but was also shaped by ongoing Olympic cycles. Indeed, for the last 20 years, East Asian geopolitical rivalries have spurred competitive hosting among Japan, China, and South Korea: Japan watching Beijing 2008 as it planned 2016 and 2020, South Korea watching both as it prepared the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Games, China jumping in to host the 2022 Winter Olympics to immediately follow Japan, and so on. Olympics hosting has become its own geopolitical sport.

All organized sports are built temporally on a conjunction of cyclical (one play after another, one game after another, one season after another, etc.) and linear movements (a faster record time replaces an earlier time, and athletes’ careers, a team’s history, etc.). What marks the OM as distinctive is the powerful ways in which the rhythms of its calendar, from detailed protocols of host bidding to legacy planning and curating, organize the efforts of cities around the world as well as the operation of some four dozen sports, creating simultaneity and competitive pressures. The Olympic temporal regime has come to impose a standardizing framework on global sport, within which each city, each Games, and each sport strives to craft a distinctive appeal.

The standardization of difference is an essential feature of globality, and the OM has been one of the most effective forces in bringing about this condition of contemporary life.

Conclusion: OM governance and rhetorical self-entrapment

Given the above characterization, it would be reasonable to assume that a transnational movement with jurisdictional tentacles reaching throughout global sport, financed by one of the world’s most profitable brands and proselytizing the most expansive claims about the beneficial roles of sport in human life would be omnipotent and unassailable. In fact, it has courted controversy, criticism, and resistance throughout its history. To its sharpest critics (e.g., Hoberman 1986, Lenskyj 2008, Zirin 2007), the IOC is a deeply corrupt organization, cynically using a gauzy humanism as a cover for its self-aggrandizement. Even its supporters have been dismayed by its political timidity and slow progress towards institutional transparency and towards more fully realizing its animating vision (e.g., Kidd 2010).

And yet, the arc of historical experience for the Olympic Movement has slowly bent from a more exclusive to a more inclusive vision of sports; what was originally the preserve of the white privileged amateur Euro-American male has become increasingly a much more open field of opportunity. In part, this comes from the persistent demands and agitations of outside forces and interests. Equally important, though, as the OM has become ever larger, richer, and more dominant, it has become ever more exposed to pressures of its own making. The Olympic Movement and its central organ, the IOC, is an example (perhaps a rare example) of how powerful interests can be made vulnerable to what we might call “rhetorical self-entrapment” and the revenge of unintended consequences.

In particular, the OM faces at least three sources of vulnerability. Its first exposure is simply the grand public scale and the long timeline of its primary production, the Summer Games. When the scale of investment by the IOC, by the local host city and country, by the broadcast media and commercial sponsors is so massive, when the media exposure is so global, and when the prestige of so many nations is on the line, even an institution with the powers of the IOC can find (and has found) itself compromised and challenged by unanticipated developments (and even, we might say, the anticipation of being overtaken by the unanticipated).

A second source of vulnerability and fulcrum for change lies in the OM need to define and defend distinctions that can prove elusive and even indefensible. It operates multi-sport competitions on a massive scale, all of which must be plausibly equitable to gain any acceptance. And yet, consider three fundamental debates about participant subjectivities that have forced continual reconsideration and recalibration by the Olympic Movement.

As noted above, the slow increase and now nearly equal participation by female athletes has required a deeply problematic effort to identify just what counts as a male-female binary in sports competition. The IOC began sex-testing in the 1960s, but its every attempt since then has proven to be unsupportable. Initially, it required demeaning, mandatory on-site anatomical inspections of all female participants, replaced a decade later by chromosome testing (the Barr body test), which in turn was superseded by genetic DNA testing in the 1990s. Yet again this failed to document the presumed male-female binary, and was replaced by endrocrinological PCR testing in the present century, although deception has never been discovered, even as legitimate athletes’ reputations were attacked. The most recent controversies (e.g. about runners Caster Semenya and Dutee Chand) center on hypoandrogenism, that is, women who naturally produce higher levels of testosterone, but scientific opinions remain inconclusive about the impact of such levels on competition. Trans-athletes, admitted to some sports competitions in Rio 2016 and who will compete in Tokyo, further undermine any rigid sex binary.8 There is a strong case to be made that in many sports, sex dichotomy is an unnecessary classification, and other standards (weight classes, testosterone levels) could replace it (Kerr and Obel 2018, Krieger et al. 2019, Pieper 2016, Sailors 2016).

Equally problematic over the decades has been OM efforts to determine the limits of the “natural” sporting body. It seeks to insure fair competition among Olympic bodies in the face of constantly evolving technological and pharmacological interfaces and intrusions that enhance elite sports performance (Geeraets 2018, Miah 2010, Schantz 2016). To seek the Olympic imperative of “faster, higher, stronger” elite athletes are always fashioning themselves as cyborgian bio-mechanical entities (Kelly 2017), and the OM faces a Sisyphean task in adjudicating and justifying.

The dissolving lines between the natural and the artificial bear upon another distinction that is testing OM’s own sport philosophy, that between ability and “disability.” In furthering its goals of diversity and inclusiveness, it is bringing the Olympics ever closer to the Paralympics, in scheduling and venues and events, but also in requiring its sponsors now to commit to advertising in both and to equally display the two Games logos. This close juxtaposition raises questions about whether there really are clear lines between the two categories of athletes. Is the high-tech prosthesis that Japanese Paralympic sprinter Itani Shunsuke wears really different from the new Nike Vaporfly running shoe that is propelling Olympic marathoners to record times? Indeed, as with greater integration of male/female events, by the logic of the Olympism itself, we can readily conceive of a closer integration of the Olympics/Paralympics with coordinate events (much as wheel-chair athletes compete side-by-side with other runners at the Boston Marathon) and even events structured to allow equitable competition among all bodies.

Paralympic sprinter Itani Shunsuke in training.

Credit: Tanaka Chisato, Japan Times

Indeed, there are a few voices within the OM that recognize the powerful demonstration effect of Paralympics by elite athletes that disability need not be seen as special needs but also as special talent and character. As Featherstone and Tamari (2019:5) put it:

“The Olympics and elite sports generally valorize heroic performances and a willingness to endure pain for higher achievement. The Paralympics takes this further. It goes beyond heroic performances to offer the commitment and dedication to a way of life that in many ways exemplifies the heroic life. Paralympic competition becomes a school for the will and the life project to demonstrate one’s ability and rise above disability.”

In such ways, the OM is changing, as often as not by the virtues it claims for the Games as by the vices brought to light by critics. Holding it accountable for its own rhetoric has been among the most effective strategies of amelioration. Its Olympic Aid program from 1992 (reorganized as Right to Play in 2000) and the more recent Olympic Refuge initiative seek to align the OM with the Sport for Development and Peace movement (Henry and Hwang 2014). Embarrassed by criticism in 2008 that it was complicit with China’s crackdown on protests before and during the Beijing Olympics, and angered by Russian heavy-handedness in the 2014 Sochi Olympics, the IOC added an explicit anti-discrimination clause for host cities, which deemed any form of discrimination with regard to race, religion, politics, or gender to be incompatible with the Olympic Movement. In 2016, over 50 LGBTQ athletes participated in the Rio Olympics. The guidelines will allow more transgender athletes to compete in the future. Indeed, in 2017, the IOC felt compelled by pressure from Human Rights Watch and other leading organizations to strengthen its Host City Contract even further to insure compliance. The OM is susceptible to and not immune from challenge in its own terms. The Olympic Games in fact can be a vehicle (cumbersome, reluctant, to be sure) for the extension of human rights to protect a variety of social categories and statuses to ensure equal participation and fair treatment.

These and other deep controversies reveal that sports—especially the Olympics—have been one of the most influential public stages for dramatizing the modern conundrum: for all of our efforts, strenuous and continuous, to construct and codify and police the distinctions of modern life, we are equally challenging and questioning and eroding those very distinctions.

The Olympic Movement is unique in the world of global sport and uniquely powerful for its distinctive qualities, especially its self-perpetuating political structure and economic monopoly on the one hand and its pious, public professions of Olympism as a balance of body, will, and mind, as a combination of effort, exertion, and achievement—a contest between the Olympic Brand and the Olympism philosophy.

And the temporal structure of the Olympics and the distributed geography of hosting leads each Olympics to strive for twin goals, both exemplifying the generic form of an Olympic Games (with its rigid IOC-imposed stipulations) and producing a uniquely memorable and consequential mega-event–fitting in and standing out simultaneously.

We can see these twin imperatives in their nascent form in the 1964 Olympic games and in their mature form in the recent Olympics, including the upcoming 2020 games. It is tempting to characterize and discount the crass commercialism and the lofty idealism as a hypocritical and disabling contradiction at the heart of the Olympic Movement. But it is also possible, and I think more analytically productive, to see this as a dynamic and dramatic entanglement, as a mutual conditioning that has demonstrated its potential for progressive as well as regressive outcomes. The Olympics may be fun to watch, but more valuably, they are good to scrutinize—and maybe even better to change.

References

Boykoff, Jules. 2016. Power games: A political history of the Olympics. London: Verso.

Brittain, Ian, and Aaron Beacom, eds. 2018. Palgrave Handbook of Paralympic Studies. London and New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Carter, Thomas F. 2012. “The Olympics as Sovereign Subject Maker.” In Watching the Olympics: Politics, power and representation, edited by John Peter Sugden and Alan Tomlinson, 55-68. New York: Routledge.

DaCosta, Lamartine. 2006. “A never-ending story: The philosophical controversy over Olympism.” Journal of the Philosophy of Sport 33 (4):157-173.

Chappelet, Jean-Loup, and Emmanuel Bayle. 2016. “From Olympic administration to Olympic governance: Challenges for our century.” Sport in Society 19 (6):737-738.

Featherstone, Mike, and Tamari Tomoko. 2019. “Olympic Games in Japan and East Asia: Images and Legacies: An Introduction.” International Journal of Japanese Sociology 28 (1):3-10

Geeraets, Vincent. 2018. “Ideology, Doping and the Spirit of Sport.” Sport, Ethics and Philosophy 12 (3):255-271.

Gold, John Robert, and Margaret M. Gold, eds. 2017. Olympic cities: City agendas, planning, and the world’s games, 1896-2020. Third edition. New York: Routledge.

Hamada Sachie 浜田 幸絵 2018. 〈東京オリンピック〉の誕生: 一九四〇年から二〇二〇年へ [Formation of the “Tokyo Olympics”: From 1940 to 2020]. Tokyo: 吉川弘文館

Hoberman, John M. 1986. The Olympic crisis: sports, politics, and the moral order. New Rochelle, NY: Arstide D. Caratzas.

Holt, Richard C., and Dino Ruta, eds. 2015. Routledge handbook of sport and legacy. London: Routledge.

Horne, John, and Garry Whannel. 2012. Understanding the Olympics. Abingdon [England] and New York: Routledge.

Houlihan, Barrie. 2012. “Doping and the Olympics: Rights, responsibilities and accountabilities (Watching the athletes) ” In Watching the Olympics: Politics, power and representation, edited by John Peter Sugden and Alan Tomlinson, 165-181. New York: Routledge.

Howe, P. David. 2012. “Children of a lesser God: Paralympics and high-performance sport ” In Watching the Olympics: Politics, power and representation, edited by John Peter Sugden and Alan Tomlinson, 166-181. New York: Routledge.

International Olympic Committee. 2019. Olympic Charter. June 26.

International Olympic Committee and the Tokyo Organizing Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (TOCOPG), Host City Contract.

Ishizaka Yuji 石坂 友司. 2018. 現代オリンピックの発展と危機1940-2020 [Development and crisis in the modern Olympics, 1940-2020]. Kyoto: 人文書院.

Ishizaka Yuji 石坂 友司, and Matsubayashi Hideki 松林秀樹. 2018. 一九六四年東京オリンピックは何を生んだのか[What did the 1964 Tokyo Olympics bring forth?]. Tokyo: 青弓社.

Jansen, Joost, Gijsbert Oonk, and Godfried Engbersen. 2018. “Nationality swapping in the Olympic field: Towards the marketization of citizenship?” Citizenship Studies 22 (5):523-539

Kelly, William W. 2013a. “Japan’s embrace of soccer: Mutable ethnic players and flexible soccer citizenship in the new East Asian sports order.” International Journal of the History of Sport 30 (11):1235-1246.

Kelly, William W. 2013b. “Adversity, acceptance, and accomplishment: Female athletes in Japan’s modern sportsworld.” Asia Pacific Journal of Sport and Social Science 2 (1):1-13.

Kelly, William W. 2017. “Sport and the artifice of nature and technology: Bio-technological entities at the 2020 Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games.” Global Perspectives on Japan 1 (1):155-174.

Kerr, Roslyn, and C. Obel. 2018. “Reassembling sex: reconsidering sex segregation policies in sport.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 10 (2):305-320

Kidd, Bruce. 2010. “Human rights and the Olympic Movement after Beijing.” Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics 13 (5):901-910.

Kietlinski, Robin. 2011. Japanese women and sport: Beyond baseball and sumo, Globalizing Sport Studies. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Krieger, Jörg, Lindsay Parks Pieper, and Ian Ritchie. 2019. “Sex, drugs and science: the IOC’s and IAAF’s attempts to control fairness in sport.” Sport in Society 22 (9):1555-1573.

Lenskyj, Helen Jefferson. 2008. Olympic industry resistance: Challenging Olympic power and propaganda. Albany: SUNY Press.

Lenskyj, Helen Jefferson, and Stephen Wagg, eds. 2012. Palgrave Handbook of Olympic Studies. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

MacAloon, John J. 2006. This great symbol: Pierre de Coubertin and the origins of the modern Olympic Games. London: Routledge. Second revised edition.

McFee, Graham. 2012. “The promise of Olym;pism.” In Watching the Olympics: Politics, power and representation, edited by John Peter Sugden and Alan Tomlinson, 36-54. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York: Routledge

Miah, Andy. 2010. “Towards the transhuman athlete: Therapy, non-therapy and enhancement.” Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics 13 (2):221 – 233.

Naul, Roland. 2008. Olympic education. Oxford: Meyer and Meyer.

Niehaus, Andreas, and Max Seinsch, eds. 2007. Olympic Japan: Ideals and realities of (Inter)nationalism, Bibliotheca Academica Soziologie. Wurzburg: Ergon Verlag.

Pieper, Lindsay Parks. 2016. Sex testing: Gender policing in women’s sports, Sport and society. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Sailors, Pam R. 2016. “Off the beaten path: Should women compete against men?” Sport in Society 19 (8-9):1125-1137.

Schanen, Naomi. 2016. “Celebrating Japan’s multicultural Olympians: Meet the athletes flying the flag and challenging traditional views of what it is to be Japanese.” Japan Times, August 17.

Shachar, Ayelet. 2011. “Picking Winners: Olympic Citizenship and the Global Race for Talent.” Yale Law Journal 120 (8 (2088)):523-574.

Shimizu Satoshi 清水諭, ed. 2004. オリンピックスタデェーズ:複数の経験・複数の政治 [Olympic Studies: Discrepant Experiences and Politics]. Tokyo: せりか書房.

Schantz, Otto J. 2016. “Coubertin’s humanism facing post-humanism – implications for the future of the Olympic Games.” Sport in Society 19 (6):840-856.

Sugden, John Peter, and Alan Tomlinson, eds. 2012. Watching the Olympics: Politics, power and representation. New York: Routledge.

Young, Kevin, and Kevin B. Wamsley, eds. 2005. Global Olympics: Historical and sociological studies of the modern games, Research in the Sociology of Sport. Amsterdam and Boston: Elsevier JAI.

Zirin, Dave. 2007. “The Olympics: Gold, guns, and graft.” In his Welcome to the Terrordome, 126-147. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Notes

While the Summer Olympic Games generate world attention and huge financial income (for the IOC, though seldom the host city), they are but the headline mega event of an increasing roster of global sports gatherings now operated under the auspices of the Olympic Movement. As mentioned above, the Tokyo Summer Paralympics, increasingly paired with the regular Olympic Games, will use the same venues and facilities for 22 sports, beginning two weeks after the OG Closing Ceremony (avoiding Japan’s mid-month Obon holidays), running from August 25 to September 6. A separate Winter Olympic Games have been held quadrennially since 1924, though its scale of participation and audiences are far narrower than the Summer Games. Additionally, the OM has recently initiated the Youth Olympic Games (from 2010) and has absorbed in its orbit the Special Olympics, and Deaflympics.

For me, among the most useful general studies of the Olympic Movement are Boykoff 2016, Gold and Gold 2017, Horne and Whannel 2012, Lenskyj and Wagg 2012, Sugden and Tomlinson 2012, and Young and Wamsley 2012. For the Paralympics, Brittain and Beacom 2018 is a recent compendium. Japan’s Olympic experience is well covered in Hamada 2018, Ishizuka 2018, Ishizuka and Matsubayashi 2018, Niehaus and Seinsch 2007, and Shimizu 2004.

For a complete list of discontinued sports, https://www.topendsports.com/events/discontinued/list.htm

The criteria may be found at https://stillmed.olympic.org/Documents/Commissions_PDFfiles/Programme_commission/2012-06-12-IOC-evaluation-criteria-for-sports-and-disciplines.docx.pdf

Which is wrong, of course. Male and female is a sex binary (referring to biological sex differences of anatomy or secondary sex characteristics), not a gender binary (which refers to personal identification with cultural constructs of masculinity and femininity). Unfortunately, the OM continues to conflate and confuse sex and gender.

The current IOC guidelines stipulate that female-to-male transgender athletes can compete without restriction. Male-to-female transgender athletes must document that their testosterone level in serum has remained under 10 nanomoles per liter for the previous 12 months.