Abstract: Japan has so far seen foreign workers as a stop-gap solution to intensifying labor shortages, as manifested in the labor import scheme for the Olympics. However, due to a gathering demographic crisis, the labor shortage will not disappear when the Olympics ends. Japan needs to create a social environment where immigrants can more easily fit in. Perhaps the 2020 Olympics, with all its promises and challenges, will be an opportunity for Japan to envision a new form of society and redefine its national identity from an exclusively monoethnic monocultural one to an embracing, inclusive and diverse one.

The Tokyo Olympic Games has brought excitement and stimulation to Japanese society, but it has at the same time exposed many issues confronting this country. Among the challenges, one of the most troubling ones is a severe labor shortage. Japan is the oldest society in the world with a declining population. Nearly 28% of the population in 2018 was over the age of 65. The work force is ageing rapidly: Japan’s agriculture is supported by famers at an average age of 67.1 In the physically demanding occupation such as construction, 34% of the 4.92 million workers in 2016 were older than 55 while only 11% were under 29.2 In 2017, one out of seven construction workers were older than 65.3 There are many jobs, but few takers.4 Such a labor shortage ahead of the Tokyo Olympics, which entails huge construction projects, means three possibilities: over working the current worker force, delaying or suspending other construction projects to divert labor, and importing foreign workers. Japan has exercised all three options.

According to a report released by Building and Wood Workers’ International (BWI)—an international union of construction workers, workers at various Tokyo Olympics sites were pressured to work egregious overtime hours in order to complete the projects on time, leading one 23-year old worker to commit suicide after clocking 190-hours of overtime the previous month.5

The concentration of the workers on the Olympics related projects also drew labor from other public projects. An elementary school in my Tokyo neighborhood has been under construction for four years, and the children who are currently in their fourth grade spent their first three years taking classes in a temporary structure adjacent to a huge muddy construction pit and still have to be chaperoned to a nearby high school for P.E. classes or Undōkai (Sports Festival) because the sports field is not yet finished.

Facing such an acute labor shortage, the Japanese government in 2014 implemented a scheme to bring in foreign workers, first through the Technical Internship and Training Program (TITP) and then the Designated Activities visa category. Under this scheme, foreign workers first enter as technical interns for a maximum of three years, and are then allowed to stay for two more years with a Designated Activities visa. Those who had returned to their home countries upon finishing the TITP were allowed to come back to work for two to three additional years.6 This plan was considered a temporary solution to the one-time Olympic expansion of construction-related labor needs. The long-term goal, according to the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT), is to improve work conditions and training systems to attract more domestic young people and bring in more women to combat the labor shortage. The labor import scheme is said to be an emergency scheme adopted to ensure the Games’ success, and is to be terminated in 2020 when the construction for the Olympic Games is completed.7 By the end of 2018, there were 68,604 foreign construction workers in Japan, a 434.7% increase from 12,830 in 2011.8

However, now with the construction for the Tokyo Olympic Games nearly finished, are these workers all returning to their home countries of Vietnam, China, the Philippines or Indonesia? Has Japan’s construction industry recruited enough young people and women to be self-sufficient, as proposed in the original plan?9 It doesn’t seem so. In November 2016, the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) and Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) amended the regulations to create a third stage of the visa status category of TITP—TITP3, officially extending the duration of technical internship in many categories, construction included, to 5 years, effective from November 1, 2017.10 A more drastic policy change was announced in the fall of 2018. On April 1, 2019 a new plan was enacted to bring in 345,150 foreign workers with “Specific Skills” (特定技能) within the next five years. Construction workers were among the 14 categories of workers to be brought in, along with other sectors with severe labor shortages such as care work, food and beverage, and agriculture. Under this new law, foreign workers that fit the skill criteria can stay in Japan for up to 5 years as Specific Skilled Workers I (SSW1). Upon finishing the initial five years, if they pass the specific skill tests determined by their profession, they are allowed to stay and work in Japan indefinitely. Workers in the category SSW2 are treated the same as people with an “Engineer and Foreign Service and Humanity” visa: They can bring in their family members and eventually become eligible for permanent residency.

This policy change reflects the government’s acknowledgement of the severity of Japan’s demographic crisis and its intensifying influence on this country’s economy and social life. However, neither the Japanese government nor the Japanese people have adequately grasped the implications of bringing in so many immigrants, who when contributing labor will also demand a decent life in Japan. In what follows, this essay introduces Japan’s policy stances toward immigration in the post-war decades, and calls attention to the problem of integration which will affect Japan in the long run.

Temporary Workers or Long-term Residents: Japan’s Immigration Dilemma

The labor import scheme for Olympic Games -related construction work exemplifies the tenets of Japan’s post-war labor migration policy— restrictive and selective. It expresses the government’s desire to treat labor imports as a temporary measure and labor migrants as disposable manpower, and highlights its resistance to openly accepting immigration.

Japan’s labor migration policy is first of all selective, prioritizing those in professional occupations and with higher education credentials (Tsukazaki 2008; Murata 2010; Akashi 2010; Oishi 2012). According to the 6th Employment Policy Basic Plan of 1988, foreigners who have professional and technical skills are considered resources for revitalizing and internationalizing Japan, and therefore “as many as possible should be accepted” (kanō na kagiri ukeireru) (IPSS 1988). In 1990, the revised Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (ICRRA) created fourteen employment visa categories. Thirteen of these visas are designated for highly skilled migrants, including such classifications as “engineer,” “investor/business manager,” “intra-company transferee,” “specialist in humanities and international services,” and “professor.” In 2003, the E-Japan Strategy II, a national policy to improve development in Japan’s IT sector, included a plan to accept 30,000 highly skilled migrants (especially IT workers) by 2005 (Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet 2003). The Japanese government’s attempts to attract professional migrants continued. In 2012, the Ministry of Justice proposed a point system for “highly skilled talent” (kōdojinzai pointo) in which individuals are given points according to their level of education, employment situations, research outputs, and salaries. Foreigners with higher points enjoy privileges such as a shortened residence requirement for permanent residency. In 2015, the new visa category “Highly Skilled Professional” (kōdosennmonshoku) was created. Though ultimately involving a relatively small number of people, those that did qualify for this category were granted a five-year visa and early eligibility for permanent residency along with other benefits, including permission to bring in caretakers, either their parents or household servants (MOFA 2015).

In contrast to its courteous attitudes toward professional migrants or people with higher education, Japan has been reluctant to accept so-called unskilled workers. The same 1988 plan states that the entry of unskilled labor (tanjun rōdōsha) is “to be dealt with extreme caution” (jūbun shinchō ni taiō suru) (IPSS 1988). As a result of such caution, “side doors” –those visa categories that are not designated for working in Japan—were created in an attempt to recruit workers while maintaining the appearance of prohibiting low-skilled labor. These include categories such as “Entertainer”—a visa designated for dancers, musicians, artists, sportsmen, and people working in the entertainment business (MOJ 2019), which then became a channel to supply workers for the numerous hostess clubs and cabarets in Japan from the late 1970s on (Komai 1995; Douglass 2000; Takeda 2005); and “Long-term resident” –a visa granted to the descendants of Japanese nationals and their families.11 Though technically not a category specifically for recruiting labor, the creation of “long-term resident” status was aimed toward opening a channel for ethnic Japanese to work in Japan to supplement the country’s shrinking manufacturing labor force (Yamanaka 1995). “International student”, a status granted to those who enter the border to pursue education, has also been used as a channel to bring in labor to the service or manufacturing sectors (Liu-Farrer 2011, Liu-Farrer and Tran 2019).

The most criticized among such side doors is the Technical Internship and Training Programs (TITP). A visa category designated for skill transfer and training workers from developing countries has been used as a major channel for importing manual labor since the early 1990s. For the Tokyo Olympic Games, one solution to the shortage of construction workers is to use TITP to recruit foreign workers. However, as the BWI report states, TITP workers “do not enjoy the same rights and working conditions as Japanese workers – their wages are on average around a third of those paid to Japanese workers, they do not enjoy the same benefits, and, crucially, they do not enjoy the rights to freedom of association and collective bargaining (BWI. 2018, p.9).”12

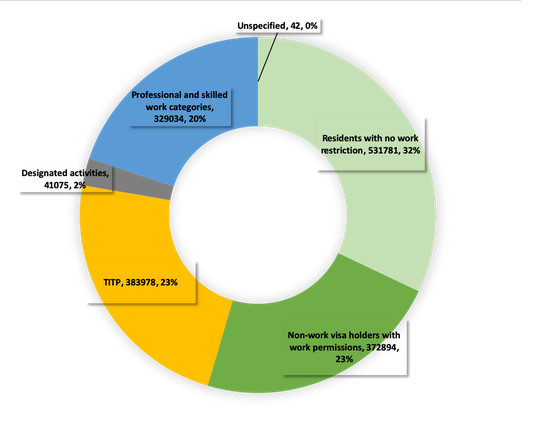

By Oct 2019, over 1.6 million foreign nationals were reported to be working in Japan, and among them, 23.1% were technical interns, and another 21% were international students. In other words, nearly half of foreign workers in Japan were “side door” labor migrants.13

Figure 1. The distribution of foreign workers in different status categories in 2019. Source: MHLW.

However, importing manual labor was no longer avoidable. The hard realities- a shrinking workforce, the closing down of small and medium size firms for lack of labor, and the disappearance of rural municipalities due to depopulation— forced the Japanese government to accept that importing foreign workers has to continue beyond the 2020 Olympics.

The creation of the Specific Skilled Workers (SSW) categories marks a major transition in Japan’s labor migration policy. Japan, for the first time in its post-war history, is accepting manual labor. However, this program is again portrayed as temporary labor migration, not an immigration policy, as PM Abe emphasized immediately after passing the plan: “As we have repeatedly stated, it is not an immigration policy that will increase the permanent residents. Do not mix them, please.”14 The Upper-house Member Wada Masamune told his constituents that this plan was “just borrowing foreign workers within a fixed period, it is not ‘Immigration’.”15

However, such political discourses are wishful thinking and the history of similar policies in other countries has shown that this ‘borrowing’ approach does not work. As the Swiss playwright Max Frisch famously remarked upon observing the social and demographic consequences of the guest worker program in Switzerland in the mid-20th century, “We asked for workers, but human beings came.” Japan faces a demographic crisis, a problem temporarily ‘borrowing’ foreign workers cannot solve. Now that wider channels have been opened for eventual settlement, it is imperative for Japan to better integrate the incoming migrants—many of whom are potentially long-term settlers— and to envision what Japan as a nation is becoming with this increasing immigration.

Integration Challenges

The construction sites of the Tokyo Olympic Games exposed the immediate challenges of integrating migrant workers. For example, the same BWI investigation reports lower safety standards for migrants on the sites of Olympic projects. Although Japanese law stipulates that employers are responsible for establishing the health and safety procedures for foreigners, it has not been consistently enforced on the Olympic construction sites because of language difficulties. All materials on health and safety procedures were only in Japanese (BWI 2018).

Language might be the first hurdle migrant workers confront after entering Japan. However, just providing some language training is not sufficient to integrate them. Continuous immigration means that more comprehensive institutional changes are needed. So far, given the “no immigration” discourse, there isn’t a nation-wide program to facilitate immigrants’ integration. Nonetheless, immigration is taking place on the ground in Japan. By 2020, over 2.8 million foreign residents were registered in Japan and over half a million immigrants have become naturalized Japanese citizens. In a recent book (Liu-Farrer 2020), I have described this pragmatic migratory process. Despite the fact that Japan has not been considered an immigrant country, people stay because they have found loved ones, have landed a job, have developed attachment to this society, or because they have lost touch with their home countries. Most of the immigrants we interviewed in the past two decades tried to learn the language and figure out the rules of the society, and found their economic niches and social circles. Some of them thereby developed a sense of belonging to Japan because of the tangible links they have established with this society.

However, individual immigrants usually bear the burden to integrate, or assimilate, into Japanese society. They can use more institutional and social support in their settlement process. This is because immigrants are not the sole stake holders in their integration. If the country needs “human resources”, they need to adapt to the needs of these humans. Japanese policies are inadequate in this regard. As research on highly skilled migrants has pointed out, many institutional frameworks, such as tax and pension schemes, the education system, as well as Japan’s corporate culture and employment system were designed with the native population and domestic labor market in mind (Oishi 2012, Hof 2018, Liu-Farrer and Shire, forthcoming). As a result, Japan hasn’t been able to retain the “global talent” that it hoped to keep.

Schools in Japan particularly lag behind the immigration trend. The current mono-cultural national education system has not made schooling experience easy for children of immigrants. The inwardly oriented education and negligible encouragement for diversity have not only halted many immigrant children’s education mobility but also alienated them emotionally (Liu-Farrer 2020).

With the creation of SSW visas, regardless of what politicians claim publicly, the government seems to realize that immigration is taking place. The Ministry of Justice issued “Comprehensive Measures for Acceptance and Coexistence of Foreign Nationals.” For FY2018-2019, it allocated 21.1 billion yen for such migrant integration programs. (Oishi, forthcoming). Although a positive step, these measures still focus on management and acceptance, and “harmonious co-existence,” drawing a line between Japanese and foreign nationals.

What policymakers are reluctant to envision is a multicultural Japan and a multi-ethnic Japanese nation. This exclusionary ethno-nationalist perspective hinders integration. Studies show that even children who were born and have grown up in Japan find it difficult to assume a Japanese identity (Liu-Farrer 2020). This lack of identification with the country they grow up in indicates the crisis of integration. This failure has large ramifications because, given Japan’s low fertility and demographic crisis, the country’s well-being is dependent on the productivity of the younger generation.

Conclusion

Japan has so far seen foreign workers as a stop-gap solution to intensifying labor shortages, as manifested in the labor import scheme for the Olympics. However, the labor shortage will not disappear when the Olympics ends. Demographic crisis is a long-term structural problem that can’t be addressed by temporary labor imports. Not only is it insufficient, it is unsustainable: there isn’t a bottomless temporary labor pool to be drawn from. The labor supply is also drying up in countries around Japan. China, the main labor sending country for the past 30 years, is facing its own challenges of a rapidly ageing population. Japan might be able to recruit more workers from Vietnam or Indonesia for now, but these countries’ economies are also rapidly developing and growing opportunities at home will lessen Japan’s appeal, especially given the lack of support for foreign workers.

This shortage has already manifested itself. The Ministry of Justice announced in January, 2020 that starting from April 1, 2020, the previously excluded migrants—the run-away trainees, people who visit Japan on short-term visas (e.g. tourist visa) and international students who have lost school affiliations—would now be eligible to take the tests to qualify for the Specific Skill Worker visa. Apparently, it has been difficult to meet the target number of SSWs from outside Japan. By September 2019, only 210 people were granted this status, an unanticipated setback for policymakers who assumed that recruiting enough workers would be relatively easy. Crisis begets flexibility; to fulfill its goal of recruiting 345,150 workers by 2025, the government is relaxing criteria for eligibility so that anyone interested can apply, even those it might once have deported for visa violations.

Instead of creating scheme after scheme to import temporary labor, Japan needs to ponder how to create a social environment where immigrants can more easily fit in and feel at home. Japan is a society with a high level of civility. Immigrants themselves appreciate this (Liu-Farrer 2020). But so far, it still sees itself in ethno-nationalist terms. The identity markers of lineage and culture still dominate people’s imagination of what constitutes Japaneseness. The 1964 Tokyo Olympics marked Japan’s transition into a strong global economy. Maybe the 2020 Olympics, with all its promises and challenges, will be an opportunity for Japan to envision a new form of society and redefine its national identity from an exclusively monoethnic monocultural one to an embracing, inclusive and diverse one.

References

Akashi, Junichi. 2010. Imin Kennkyū to Nyūkoku Kanri: Nyuukok Ukanri Seisaku-1990 Nentaisei no Seiritsu to Tenkai [Japan’s immigration control policy: Foundation and transition]. Kyoto: Nakanishia Shuppan.

Building and Wood Worker International (BWI). 2018. “The Dark Side of the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics.”

Hof, H. 2018. ‘‘Worklife Pathways’ to Singapore and Japan: Gender and Racial Dynamics in Europeans’ Mobility to Asia’. Social Science Japan Journal 21(1): 45–65.

IPSS. 1988. Dai 6-ji Koyō Taisaku Kihon Keikaku [The 6th basic employment measures plan]. National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.

Komai, Hiroshi. 1995. Migrant Workers in Japan. London: Kegan Paul International. Douglass, Mike. 2000. “The Singularities of International Migration of Women to Japan.” In Japan and Global Migration, edited by Mike Douglass and Glenda Roberts, 91– 120. London: Routledge.

Liu-Farrer, G. 2011. Labor Migration from China to Japan: International Students, Transnational Migrants. London: Routledge.

Liu-Farrer, G. 2020. Immigrant Japan: Mobility and Belonging in an Ethno-nationalist Society, Cornell University Press. ISBN13: 9781501748622.

Liu-Farrer, G. and An Huy Tran. 2019. “Bridging the Institutional Gaps: International Education as a Migration Industry,” International Migration. Volume57, Issue3, 235-249, doi: 10.1111/imig.12543

Liu-Farrer, G. and K. Shire. Forthcoming. “Who are the Fittest? The Question of Skills in National Employment Systems in an Age of Global Labour Mobility,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA). 2015. “Highly Skilled Professional Visa,” accessed February 25, 2019.

Ministry of Justice (MOJ). 2019. Immigration Statistics (in Japanese).

Murata, Akiko. 2010. “Gaikoku Koudo Jinzai No Kokusai Idō To Rōdō – Indojin IT En-jinia No Kokusai Idō To Ukeoi Rōdō No Bunseki Kara” [International migration of highly skilled workers: Analysis of the temporary migration of Indian IT engineers and contract labor in Japan]. Migration Policy Review 2: 74–89.

Oishi, N. Forthcoming. “Skilled or Unskilled?The Re-configuration of Skilled Migration Policies in Japan,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies.

Oishi, N.. 2012. ‘The Limits of Immigration Policies: The Challenges of Highly Skilled Migration in Japan.’ American Behavioral Scientist, 56(8): 1080-1100.

Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet. 2003. E-Japan Strategy II. Tokyo: IT Strategic Headquarters, accessed February 25, 2019.

Takeda, Jo. 2005. Firipinjin Jyosei Entāteinā no Raifusutōrī—Enpawāmento to Sono Shien [The life stories of Filipino women entertainers: empowerment and its support]. Nishinomiya: Kansei Gakuin University Press.

Tsukasaki, Yūko. 2008. Gaikokujin senmonshoku gijutsushokuno koyou mondai [Employment problems concerning foreign professionals and engineers]. Tokyo, Japan: Akashi Shoten.

Yamanaka, Keiko. 1995. “Return Migration of Japanese-Brazilians to Japan: The Nikkei- jin as Ethnic Minority and Political Construct.” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 5 (1): 65–97. doi:10.1353/dsp.1996.0002

Notes

- “農業労働力に関する統計“ https://www.maff.go.jp/j/tokei/sihyo/data/08.html

- “建設産業の現状” https://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001174197.pdf

- 建設業界人材動向レポート ”https://kensetsutenshokunavi.jp/souken/report/const/201803.php

- The construction industry’s job vacancy ratio is over 6 in 2018, meaning for every 6 job vacancies, only one of them can be filled.

- “The Dark Side of the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics,” https://www.bwint.org/web/content/cms.media/1542/datas/dark%20side%20report%20lo-res.pdf

- “建設分野における外国人材の活用に係る緊急措置” https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/houdou/pdf/140404kensetsu.pdf

- The translation is adapted from the original “当面の一時的な建設需要の増大への緊急かつ時限的措置(2020年度で終了)として、国内で の人材確保・育成と併せて、即戦力となり得る外国人材の活用促進を図り、大会の成功に万全を期する” https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/houdou/pdf/140404kensetsu.pdf

- “建設分野における外国人材の受入れ” http://www.thr.mlit.go.jp/bumon/b06111/kenseibup/plan_build/pdf_0810/190507_siryou2.pdf

- The “緊急措置”underscores “国内での確保 に最大限努めることが基本”. https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/houdou/pdf/140404kensetsu.pdf

- “新たな外国人技能実習制度について”, https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-11800000-Shokugyounouryokukaihatsukyoku/0000204970_1.pdf

- Included in this visa are also legal guardians of children of Japanese nationals (e.g., divorced spouses of Japanese nationals who have custody of the children), or other individuals considered eligible by the Ministry of Justice (MOJ 1990).

- “The dark side of The Dark Side of the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics,” https://www.bwint.org/web/content/cms.media/1542/datas/dark%20side%20report%20lo-res.pdf

- Residents with no work restrictions includes miscellaneous legal statuses that do not impose restriction on working, such as permanent resident, long-term resident, spouses and dependents of Japanese nationals or permanent residents.

- 「永住する人がどんどん増える移民政策はとらないと、今まで再三言っている通りだ。混同しないでほしい」西日本新聞 11月2日

- 和田政宗 自民党・参院議員「一定期間外国人労働者の力を借りるのであって『移民』ではない」Official blog 10月30日