Abstract: This article assesses the planning, management and repatriation of Japanese civilians in Shanghai between 1945 and 1948. It examines four interwoven dimensions of this history. The first is the removal of Japanese expatriates as the centerpiece of the Kuomintang and Allied Powers’ project to end Japanese colonialism once and for all. The second is how the Japanese community continued to exert a degree of autonomy and agency under the extremely unfavorable postwar circumstances. The third is the nature of postwar attempts to match each person with a definitive ethnic-national category. The fourth is how postwar history was experienced at the individual level among Japanese of different social strata and experiences.

Key words: Shanghai, World War II, Japanese settlers, repatriation, decolonization, treaty port, post-war East Asia

Introduction

The day was August 14, 1945.1 Fourteen-year-old Kageyama Tetsu was working at the Jiangnan Shipyard on the outskirts of Shanghai, an industrial complex that was once the crown jewel of Chinese industrial modernization. Since the early stage of the war, it was placed under the control of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. From late March of that year, Kageyama and his classmates at the Shanghai Japanese Middle School were mobilized to join the Working-Hard-for-the-Nation Student Squad (Gakuto kinrō hōkoku dai) serving the Japanese military. Their jobs included preparing and loading artillery shells, machine gun bullets and torpedoes. Shortly before noon—much earlier than usual—Kageyama’s team was dismissed and ordered to go home. This caused some anxiety among the teenagers, but no one seemed overly concerned at this point. Twenty-four hours later, with the entire Kageyama family gathered in their living room, they heard the voice of the emperor communicating for the first time with his people at home and throughout the empire. However opaque those words were, the core message was clear to everyone — the war was over and Japan had lost. Kageyama felt “all strength drained away from his body,” his mind overwhelmed by confusion and disorientation. Equally perplexing and upsetting to him was his father’s aloofness and even a sign of relief. Yet, there was one thing that seemed clear to him. His family’s life in Shanghai, where he was born and raised, and where his father had been working as a teacher for 35 years, was coming to an end.

Kageyama’s sense was correct. Although his family managed to remain in Shanghai for three more years, over 98 percent of the Japanese population in the city at the end of the war were repatriated by the summer of 1946. Recalling those days half a century later, Kageyama felt grateful that, compared with returnees from places such as Manchuria, inland China, Korea and Karafuto, his postwar experience was almost a “sweet” one.2 At least, his family remained intact throughout the ordeal of multiple relocations, first within Shanghai and eventually from Shanghai to Japan. The story of the Kageyama family is just one example of the transfer of millions of Japanese civilians in the years after 1945. Shortly after defeating Japan, the Allies started a massive project of repatriating Japanese nationals throughout Japan’s former colonies. Although many overseas Japanese had already started to move back to Japan on their own immediately after or even before the end of the war, the forced repatriation—arranged and facilitated by the Allied military—was part and parcel of the effort to demilitarize Japan and dismantle its fifty-year imperial enterprise.3

Although repatriation was often compulsory, the human experience related to it was not solely dictated by the geopolitical realignment led by the victorious. As Lori Watt points out, “the unmaking of empires everywhere is a complex process, and the human remnants of Japan’s empire — those who were moved and those who were left behind — served as sites of negotiation for the process of disengagement from empire and for the creation of new national identities.”4 Harboring one of the most sophisticated and long-standing Japanese expatriate communities during the prewar and wartime periods, Shanghai was an important site where the complex politics surrounding the postwar repatriation of Japanese and the dismantling of the Japanese empire unfolded. As of August 1945, over 48,000 Japanese civilians lived in Shanghai. They would be joined by 80,000 more from surrounding regions shortly after the war. From September on, they were confined in the Japanese Nationals Concentration Zone (Riqiao jizhong qu), a restricted area set up by the Chinese authorities in Shanghai’s former International Settlement, and strictly regulated until they embarked for the homeland.

The management and repatriation of Japanese civilians in Shanghai between 1945 and 1948 in many ways exemplifies how mass population transfer was planned, negotiated, and executed throughout the former Japanese empire in postwar East Asia and the Pacific. At the center of this story are four interwoven dimensions that will be explored in this essay. The first, as mentioned above, is the removal of Japanese expatriates as the centerpiece of the project to end Japanese colonial rule. Although the dissolution of the Japanese empire is often framed as an example of “third-party (American) decolonization”—and from a logistical perspective, at least, this is also true in the case of Shanghai—the Chinese and the Americans differed in both motivations and approaches when handling overseas Japanese civilians. However strong the American influence was during the process,55 the Guomindang government lacked neither the incentive nor the authority to act independently in decolonizing China’s largest treaty port and unmaking the Japanese empire there. For a number of reasons, Shanghai was selected by the GMD authorities as a showcase for managing and transferring Japanese civilians that was to become a model for the rest of China.

The second dimension is how the Japanese community managed to exert a certain degree of autonomy and agency even under the extremely unfavorable political circumstances in the wake of Japan’s defeat. This was in part due to the fact that they were de facto left to their own devices by the postwar Japanese government and US occupation authorities in Japan. Equally important was the continuation of some prewar political, socio-economic, and spatial configurations of Shanghai’s Japanese society. After the war, a number of prominent and well-connected Japanese settlers continued to play a leading role in the Japanese self-governing organizations under the supervision of the Chinese authorities. They strove to keep repatriation organized and the life in the concentration zone orderly, at a time when many felt confused, frustrated, stressed or terrified by the prospect of forced removal to Japan. Their existence made it difficult to reduce the politics of postwar repatriation to a simplistic story of the “defeated” being dominated and displaced by the “victorious.” At the same time, however, the Japanese community itself was fraught with internal conflicts, and the perennial schism between the elite and the middle- and lower-classes continued after the war.

A third dimension that looms large is the postwar trend to match each person with a definitive ethnic-national category and return everyone to their “appropriate” homeland. In other words, the return of overseas Japanese was a process in which Japanese people were being reinvented premised on the notion that one could determine, unequivocally, whether a person was Japanese or not.5 However, the identification of “Japanese” was frequently full of tension, especially when involving situations such as mixed descent, adoptive parentage or international marriage, and many people tried to contest the official categorization in order to avoid repatriation.

All these dimensions converge on a fourth one, which is how postwar repatriation was experienced at the individual level. As John Dower famously observes, there was no single or singular “Japanese” response to the defeat apart from a wide-spread abhorrence of war, and what is fascinating is how kaleidoscopic such responses were.6 The same holds true in the case of Japanese abroad and specifically those in Shanghai. These variegated responses not only reflect one’s pre-defeat socioeconomic position within the settler society, but were constantly shaped by the repatriation process itself. In particular, personal and collective identities vis-à-vis the empire and the host society underwent much reinvention under postwar circumstances. After repatriates returned to the homeland, the social and cultural implications of their overseas experience would continue to be visible in postwar Japanese society. But overall, Shanghai was rather peculiar in providing perhaps the best shelter, security and management for civilian repatriates. Like the Kageyamas, Japanese civilians in postwar Shanghai were mostly spared the starvation, physical violence, and family breakup that were common in Manchuria and elsewhere. Nevertheless, their diverse stories provide important insights into how the postwar order and disorder were translated into the texture of people’s everyday lives.

August and September 1945: Order, Chaos, Violence, and Uncertainty

At the time the war ended, the fate of millions of overseas Japanese civilians in China and throughout the empire was pending. One hour before Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s unconditional surrender on August 15, Chiang Kai-shek delivered the famous speech calling for “requiting resentment with kindness” (yi de bao yuan), enjoining the Chinese public to differentiate innocent Japanese people from militarists and war criminals and refrain from abusive treatment or violent revenge against Japanese civilians and demobilized Japanese soldiers. On the same day, Japanese Ambassador Tani Masayuki sent a broadcast message to all Japanese nationals in China. Apart from reiterating the emperor’s injunction to “bear the unbearable” and “make every effort to preserve the Japanese nation as well as world civilization,” he called on overseas Japanese to display even greater endurance and courage than their domestic brethren, to keep composure and refrain from reckless actions, and to “respond to great changes with unchanged steadiness.”7 Nevertheless, neither the Chinese nor the Japanese authorities at this point had issued a clear plan concerning the future of the civilians. Nor had the Americans. Article 9 of the Potsdam Declaration stated only that “the Japanese military forces, after being completely disarmed, will be permitted to return to their home with the opportunity to lead peaceful and productive lives.” Prioritizing the demobilization of the Japanese army and navy, the U.S. military did not begin to pursue repatriation of Japanese civilians until September after taking into consideration a mixture of pragmatic and humanitarian factors.8

The initial policies of the Japanese government came as a disappointment to the “overseas brethren.” On August 18, the Japanese military headquarters in China urged Japanese civilians in China to “continue their activities on the continent with the forgiveness and support of the Chinese side,” and to “contribute to the Chinese economy their knowledge and techniques.”9 Japan’s ad hoc postwar government—the Council for Managing the Termination of the War (j. Shūsen shori kaigi)—did not announce its first decision on repatriating civilians until August 31— two weeks after surrender. Due to the desperate economic conditions in Japan and a serious shortage of shipping capabilities, overseas Japanese were advised to “stay put” (genchi teichaku) for the time being as conditions permitted. In the next several weeks, before the Allied occupation officially started in late September, the Japanese government vacillated over repatriation. Obviously the Japanese government lacked the capacity to initiate large-scale return of its overseas citizens; in fact, by delaying the repatriation, it still hoped to keep a civilian presence in China to protect Japanese assets and maintain Japanese technological and economic influence in postwar China.10 These attitudes of the Japanese government caused much anxiety and grievance among overseas Japanese, many of whom felt that they were deserted by their own government. As one repatriate from Shanghai wrote, at the time the war was over she had no clue whether she “would return to Japan safely, or be kept as a life-time slave in Shanghai, or be forcibly relocated to somewhere else.”11 However, it should be noted that as late as September 29 the Japanese government was still trying to have a voice on repatriation. On that day, it communicated with the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers about its plan to retrieve people from particularly dire situations, such as Japanese troops in the Philippines who were dying of starvation. But the SCAP replied by stating that “repatriation of Jap Nationals is being conducted in accordance with policies formulated by this office and will be announced in a few days.” Thereafter, as part of a policy to take control of Japan’s foreign relations, SCAP took up the repatriation issue.12

For the GMD government, total deportation of Japanese nationals was to be pursued only after valuable elements of the Japanese presence in China—such as certain military and medical personnel serving the GMD army—were mobilized and put to use. More important, the GMD’s imperative immediately after the war, especially in large urban centers like Shanghai, was restoring order and security rather than repatriating foreign civilians. Throughout late August, the question of outbreaks of anti-Japanese violence in Shanghai was repeatedly addressed by the GMD military and civil leaders, many of whom cited Chiang Kai-shek’s August 15 speech on “forgetting past resentment and treating others with leniency” (bu nian jiu e, yu ren wei shan).13 Meanwhile, in order to reduce contacts between the Chinese and the Japanese, in early September the GMD leadership issued another directive instructing all Japanese civilians “to stay at their current residence or assigned location until detailed policies are announced.”14

The GMD’s prioritization of public security was well-justified. Even in Shanghai violence against Japanese civilians did occur, albeit on a limited scale. Many former Japanese settlers recalled that “the atmosphere of Shanghai’s streets changed overnight,” and “violence started to happen everywhere.”15 Some Chinese “broke into Japanese houses with muddy shoes” and “took away whatever they wanted.” In other cases, the perpetrators simply occupied the houses and expelled the Japanese dwellers. It was also reported that many Japanese, especially women and children, were robbed, spit on, and attacked with stones.16 Nevertheless, individual experience varied significantly, and positive elements are equally visible in repatriates’ accounts. Izumi Atsuhiro, a high-school student at the time, recalled that “the Chinese population of Shanghai, in part because of the cosmopolitan tradition of the city, were generally tolerant and generous toward foreigners”; moreover, he thought that Chiang Kai-shek’s August 15 speech had the effect of reducing anti-Japanese sentiments.17 According to Okazaki Kaheita, the Japanese Consul General in Shanghai, many long-term Japanese residents, who were well-connected among the local population and had witnessed Shanghai’s past political unrest, “stayed surprisingly composed and barely agonized over the Japanese defeat.”18

Some conflicts between the Japanese and Chinese in postwar Shanghai were more economic than political. For instance, Tanaka Keiko, a seventeen-year-old at the time, recalled that after her family’s shipping company was forcibly closed following the Japanese defeat, hundreds of the company’s Chinese employees gathered in front of their house every day to demand immediate payment of their salaries. This made it virtually impossible for Keiko and her mother to leave the house. Yet, the Tanaka family was fortunate enough to be helped by two Chinese servants, who continued to perform their duties, do grocery shopping, and care for the family.19 Many more similarly recorded how they relied upon Chinese friends and colleagues for protection and provisions.20 Despite the widespread violence in Shanghai’s postwar chaos, there are ample cases to show how Japanese civilians managed to mobilize personal connections to ensure their security. The existence of these connections challenges the conventional understanding of the Japanese settlement in Shanghai as an insulated community.21 It also in part explains why individual memories differ widely when it comes to immediate postwar experience. Nevertheless, this period of relative flexibility would soon give way to a more structured system of regulations by the GMD authorities.

Japanese in the new Shanghai: the concentration policy and its challenges

The GMD takeover of Shanghai began in earnest in late August 1945. On September 8, escorted by several hundred Japanese soldiers and led by General Tang Enbo—a well-known Japanophile—the Nationalist Third Front Army (TFA) marched through the core area of Shanghai. The parade was cheered on by over 200,000 people. Among them were not only several dozen handpicked Japanese civilian and military representatives, but many more Japanese settlers who joined the crowd spontaneously. For them, the arrival of the Chinese army had double meanings. On one hand, it graphically proclaimed the defeat of the Japanese empire and the end of Japanese rule in Shanghai; on the other hand, it also brought the hope of ending the postwar turmoil with clarification of how Japanese civilians would be treated and repatriated. Izumi Atsuhiro, who was then a ninth-grader and had been living with his family in Shanghai since 1942, remembered mixing with the elated Chinese crowd on North Sichuan Road that day. Impressed by the triumphant arrival of the GMD’s elite troops and their strong physique, he “for the first time felt the Japanese defeat in a corporeal way.”22

Upon his arrival, General Tang once again echoed Chiang Kai-shek’s August 15 speech:

“China and Japan should by no means follow the old path of France and Germany and endlessly feel antagonism against each other. Presented before us now is an opportunity to build a solid ground for genuine cooperation between the two nations in the future.”23

In particular, General Tang stressed that “the postwar transfer of Shanghai captures the attention of countries all over the world,” and therefore he was “determined to make it a model for the Chinese military (accepting Japanese surrender).”

On September 16, the TFA headquarters ordered all Japanese civilians outside the Hongkou area to relocate there within five days. More detailed instructions on relocation soon followed as part of the “Rules for Managing and Organizing Japanese Nationals” (Riqiao bianzu guanli banfa) announced on September 24, which for the first time used the term “Japanese Nationals Concentration Zone.” This term was carefully chosen to be differentiated from the notorious “concentration camp” (jizhong ying).24 The concentration zone was divided into four districts. The first three were adjacent to each other and located in Shanghai’s Hongkou and Yangshupu regions, where many Japanese residents of the city had been living. A fourth district—much smaller in size—was established at the core of the former International Settlement’s West District on the south side of Suzhou Creek. Remotely detached from the others, this fourth district was where the Japanese upper class resided. This group of residents, which included diplomats, large business owners and elite professionals, was also known as the kaisha-ha (Company Clique). During the prewar period, the rest of the settler community, much larger in numbers, were called the dochaku-ha (Native Clique) and consisted mostly of long-term residents of a wide range of occupations including shopkeepers, freelancers and workers who came to Shanghai seeking a better life. These settlers, generally having closer ties to the local society, had mostly concentrated in the “Little Tokyo” in Hongkou and nearby areas.25 Therefore, in following the existing patterns of residence, the concentration policy effectively reproduced the spatial separation that had always existed between Shanghai’s Japanese elite and the rest of the settler community.

Map 1 Shanghai Japanese Nationals Concentration Zone, 1945-1946 (GIS link)

For those who lived outside the concentration zone, an acute challenge now was to find accommodation for their entire family in the assigned area. Kageyama Tetsu’s family, for example, lived in Zhabei at the time. Once the relocation policy was announced, his father started house-searching in Hongkou and was fortunate enough to be able to secure a place very quickly. The family’s new residence was on the second and third floors of a small three-storied warehouse owned by a Japanese friend who ran a military supply store. The Kageyamas sold most of their furniture to their Chinese landlord and brought with them only portable items such as futon, family photos, ancestral tablets and books. The Chinese landlord also offered them protection on their way to Hongkou. Kageyama Tetsu attributed his family’s smooth move to his father’s experience as an “Old Shanghai Hand” (lao Shanghai) for thirty-five years and his “familiarity with the nature of local society.”26

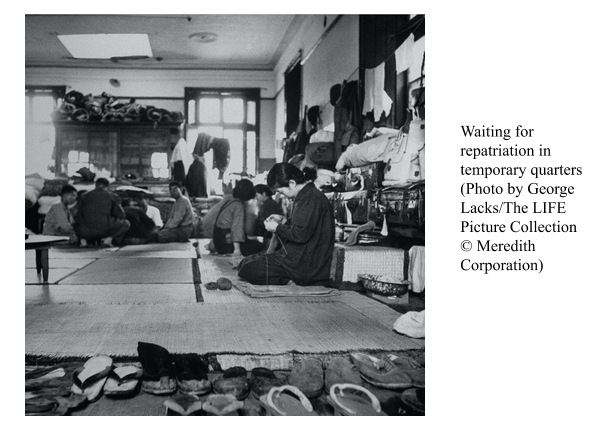

Many others told similar stories. Izumi Atsuhiro also recalled moving from Zhabei to a friend’s house in Hongkou, where his family of six lived in an eight-jō (13 square meters) room for several months.27 If space was now a luxury for those relocated, privacy was even more so. Those who were unable to find a place by themselves—many having arrived recently in Shanghai from surrounding provinces— were assigned temporary refuge in what were once warehouses, schools or other public buildings owned by Japanese. For example, the No. 9 Japanese National School on Tangshan Road became the new home of 200 or so people, with each classroom accommodating 20 to 30 people from three to five different families.28

On October 1, the TFA opened a new Shanghai Japanese Nationals Management Office (Shanghai Riqiao guanli chu). The SJNMO’s basic responsibility was summarized as follows,

“On the positive side, we need to provide Japanese nationals physical shelter as well as spiritual sustenance, to build a foundation for future cooperation between China and Japan; on the negative side, we must ensure that the Japanese make a clean break with their past errors and strictly follow the rules so that they do not transgress in the slightest. We will make every possible effort to uproot their militarist ideas and sense of superiority. In the meantime, we will thoroughly examine all Japanese personnel and assets and report to each department for appropriate handling, so that they will contribute to our nation-building project.”29

At the center of the GMD’s concentration policy was the use of the baojia system. All Japanese within the concentration zone were placed under a strictly controlled system of bao and jia, with each bao made up of ten households and each jia of ten bao. As of mid-October, a total of 79,086 Japanese civilians were registered into 114 bao and 1,100 jia, with over 90 percent of the population located in Zone One, Two and Three.30 The centuries-old baojia system had served as a basic institution of law enforcement and civil control in Chinese society. During the 1930s, it was adapted by the GMD government to combat underground communists.

The GMD authorities reinvented the baojia system in the concentration zone to achieve a twofold goal. First, it meant granting, at least nominally, the Japanese community a degree of autonomy as each bao and jia elected its own leader to take charge of neighborhood security. Second, it had important ideological and educational functions— baojia leaders were obliged to regularly attend the training sessions organized by the SJNMO and to “spread the democratic spirit among their fellow Japanese.”31 At the top of the baojia system was the Japanese Self-Governing Committee (Riqiao zizhi hui), founded five days after the SJNMO on October 6. With its internal structure mirroring that of the SJNMO, the JSGC was responsible for overseeing baojia elections, running daily administration of the concentration zone and playing a coordinating role between the GMD authorities and Japanese residents. The JSGC also facilitated the requisition of all Japanese assets that were not considered to be “daily necessities,” such as real estate, industrial equipment, precious metals, jewelry and foreign currency—the GMD authorities pledged to calculate all these assets as part of Japanese war indemnity to China in the future, and the JSGC indicated to those willing to turn in their assets that they would be properly compensated by the Japanese government. However, the close relationship between the GMD authorities and the JSGC did not relegate the latter to a mere puppet agency. One issue over which the JSGC occasionally disputed with the Chinese concerned the right to use Japanese-owned buildings within the concentration zone. In late 1945, Japanese civilians pending repatriation continued to stream into Shanghai from distant regions such as Anhui, Hubei and Hunan. Consequently, the space of temporary quarters in the concentration zone became increasingly insufficient. At the petitions of the JSGC, a number of buildings that were once confiscated and sealed up by the Chinese government were re-opened to accommodate latecomers.32

In addition to inadequate space, the concentration policy faced other challenges from its inception. For one thing, not every “Japanese national” was easily identifiable. Sometimes people tried to escape relocation by disguising or negotiating their ethnic identities. On November 4, 1945, the Shanghai police received a report on “suspicious behavior” of a couple living on Changning Road.33 Plainclothes officers sent to investigate the couple soon found that the husband did not speak fluent Chinese. In interrogation, Xu Jinghe, revealed that he was born to Chinese parents in Dalian and was adopted by a Japanese family. He had been living in Shanghai and working as a furniture broker for several years. When asked whether he was Chinese or Japanese, his answer was “stateless” (wu guoji). However, he insisted he ought to be recognized as Chinese on the ground that he was married to a Chinese woman. The “Chinese woman” in this case, Xue Yan, however, reported that she was born in Japan to a Chinese couple and returned to China when she was a teenager. She also stated that, if her husband was subject to deportation, she would have no choice but to divorce him.

In the end, based on the fact that Xu was raised by Japanese parents and was “not fluent in Chinese” (bu shan Zhongwen), the police charged him with deliberately escaping concentration, and handed him over to the Japanese Self-Governing Committee for relocation in the concentration zone. The Foreign Affairs Bureau of Shanghai supported this decision, although it conceded that Xu did not have Japanese citizenship either. In the end, security concerns ruled the day, and the Foreign Affairs Bureau stated that people like Xu who had direct Japanese connections and did not speak fluent Chinese should be identified as “Japanese” and moved to the concentration zone. However, despite Xue Yan’s Japanese background, her Chinese citizenship was never questioned throughout the case. This shows that, while language and family background constituted two criteria for the postwar identification of “Japanese nationals” in Shanghai, the definition of “Japanese nationals” could be easily expanded to include anyone who was considered a potential source of social disorder; meanwhile, being labeled as such was often simply a result of the lack of well-defined identity as either Chinese or Japanese.

But even for those who readily complied with the concentration policy, there was no clear schedule for repatriation until late 1945. In late October, the GMD authorities and the U.S. military agreed in principle that all Japanese civilians remaining in China should be deported as soon as possible.34 The American side would provide the shipping capacity required to transport repatriates from Chinese ports to Japan, whereas the Chinese authorities were responsible for repatriates’ inland transportation, concentration, and pre-embarkation check. In fact, however, during the initial months after the war, the majority of American transportation resources were used to retrieve hundreds of thousands of Allied POWs who had suffered from malnourishment and disease in Japanese camps throughout Asia including China and Japan. Meanwhile, the still dire situation in Japan whose major cities had been demolished by US bombing in the final six months of the war further discouraged the Occupation authorities from instantly receiving returnees from abroad. Moreover, Japanese civilians in Shanghai were perhaps considered low priority for repatriation because they were deemed relatively safe, especially compared with those in Manchuria where the end of World War II was followed by civil war involving Naitonalists and Communists.

By the end of 1945, The GMD authorities had grown impatient with the U.S. military’s slow pace in shifting the focus of repatriation to mainland China, not least because the densely populated concentration zone was consuming considerable Chinese resources. Under Chinese pressure, the Americans finally agreed in January 1946 to provide vessels to set in motion mass repatriation over the next five months.

Despite the GMD authorities’ active role in expediting repatriation, they were far from categorically seeking to eliminate all vestiges of Japanese presence in China. Starting in late September 1945, the authorities enacted a series of rules for retention of Japanese professionals and technicians in sixteen key industrial sectors including shipbuilding, railway, chemical industry, textile, construction and electronics. In addition, a significant number of the retained Japanese civilians were medical personnel. By mid-December, 3,115 Japanese with specialties or valued skills were registered by the SJNMO to continue their service in China, although most of them were removed from decision-making positions and placed under close surveillance by Chinese supervisors.35

Quite a number of Japanese expressed the wish to stay in Shanghai, many “feeling anxious about going back to live in Japan,” “having one’s family and social circle in China,” or “genuinely wishing to contribute to Sino-Japanese amity.”36 By the end of 1945, the SJNMO and the National government of Shanghai received several thousand petitions for naturalization and permanent residence—the most commonly cited reasons included “being attuned to Chinese traditions,” “having faith in the supreme leader of China and the Three Principles of the People,” and “the Chinese and the Japanese having the same culture and ethnicity.”37 However, these cases were almost invariably rejected for security reasons. Regarding the majority of Japanese civilians, the GMD authorities were no less determined than the Americans to send them back as soon as possible.

Another way to postpone one’s repatriation was to take part in the management of the concentration zone. Kageyama Tetsu’s father, for instance, worried about how his family of eight would survive the famine and chaos widespread in postwar Japan. Needless to say, food and other supplies in Shanghai were also scarce towards the end of 1945, not to mention the hyperinflation that aggravated the situation. However, living in the concentration zone guaranteed at least a minimum subsistence, a concern especially for those who had a big family to support. The elder Kageyama’s lifetime work experience in Shanghai and his connections in both the Chinese and Japanese communities earned him a job in the GMD’s propaganda department. As a result, the Kageyamas were permitted to stay until late 1948, by which time the economic situation in Japan had begun to improve.38

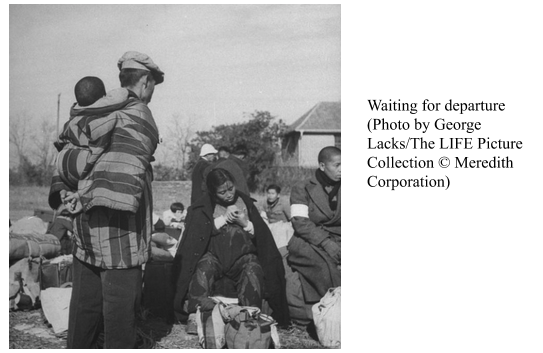

Nevertheless, most Japanese wanted to return to the homeland as soon as possible—in the concentration zone, a common punishment for minor offense was to move one’s name to the bottom of the repatriation schedule. But the homebound journey was never an easy one and entering the formal channels of repatriation did not guarantee a swift and safe return. Life in the concentration zone for most meant making a living by whatever means available, adjusting to a variety of rules, and waiting for an unspecified date of embarkation.

Living in the concentration zone: the changed and unchanged

In the concentration zone Japanese civilians were subjected to rigorous regulations. They were not allowed to leave their residence between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. Anyone who went out had to wear an armband with the characters “riqiao” (Japanese national) on it. Leaving the concentration zone was, of course, strictly prohibited without special permission. By January 1946, the SJNMO had issued only 169 such permissions. Furthermore, all deaths, births and relocation within the concentration zone were to be reported instantly to baojia leaders for the SJNMO’s record. In addition, the Japanese were forbidden to dress in Chinese-style clothing or to ride a rickshaw.39

Because most Japanese civilians had lost their jobs and income, the SJNMO put into effect a relief system that distributed 10 kilograms of rice and flour to each adult per month with half of that amount to each child. Most of the supplies came from those confiscated from the Japanese military and Japanese companies. But by late January 1946, the original ration could be maintained for just two more weeks based on the current number of people waiting for repatriation. This supply shortage no doubt contributed to the acceleration of repatriation in the following months.

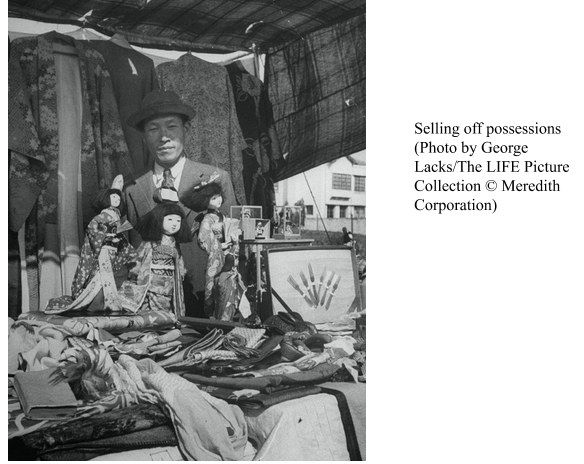

As supplies dried up, many Japanese attempted to support themselves and their families by selling personal belongings such as books, clothes, furniture and other valuable items. Second-hand Japanese goods became extremely popular on Shanghai’s flea markets, and the concentration zone attracted numerous Chinese vendors every day.40 Fifty years later, Kageyama Tetsu still vividly remembered the day he had a lengthy bargain with a Chinese second-hand trader who was interested in his father’s book collection. He was impressed by this man’s creativity in reselling and reusing everything he bought from the Japanese, for example, using a Japanese brazier for storing rice, transforming a Japanese wardrobe into a medicine cabinet, and selling Japanese kimonos to American soldiers as souvenirs.41 Izumi Atsuhiro likewise recalled how valued items such as a German-made camera and a Swiss-made clock disappeared one by one from his home. Some people made a living by selling home-made snacks and desserts. One day, on the street, Kageyama Tetsu was surprised to see his teacher—”a highly respected gentleman”—selling rice cakes and sake, which “he made using his expertise in science.” After this encounter, Kageyama “felt driven by an even stronger incentive to make every effort to survive.”42

Anxious to limit intermingling between the Chinese and Japanese, the GMD authorities once considered enforcing a ban on such selling and peddling. However, under the double pressure of the active lobbying of the JSGC and the gradual draining of relief resources, the SJNMO backed down. Sellers were allowed to continue their business as long as they properly registered and operated within designated areas.

While most Japanese lived barely above subsistence and were under surveillance, a small number of elites apparently had the means and money to get around most regulations and continue a luxurious lifestyle that was akin to the past. The Chinese continuously aired complaints that the Japanese were having “too much freedom” in the concentration zone.43 As late as February 1946, a journalist of the Republican Daily wrote that he recently visited a high-end restaurant in Hongkou, only to find himself surrounded by Japanese customers enjoying pricey Western cuisine that he could never afford. Afterwards, in a movie theater renamed “Victory Cinema” after the war, he ironically found himself to be the only Chinese among “Japanese men in lavish velvet coats, Japanese women in delicate kimonos and Japanese children in expensive cashmere sweaters.”44 Clearly, in the concentration zone, the perennial social and economic inequality within the Japanese settler community continued to exist and became even more evident under postwar scarcity. Later, many middle- and lower-class settlers would express their discontent with the Japanese Self-Governing Committee, which they accused of being dominated by the self-interested kaisha-ha.

In the ideologically and emotionally charged milieu of postwar Shanghai, settlers awaiting repatriation were made the subjects of the GMD’s ambitious re-education project that sought to “promote the spirit of democracy among the Japanese.” This started with a radical reform of the local Japanese school system and censorship of Japanese textbooks. The GMD authorities also sponsored a number of Japanese-language newspapers and magazines to be circulated in the concentration zone, including the famous Rehabilitation Daily (Gaizao ribao), and organized a variety of forums on a regular basis to have Japanese settlers “condemn Japanese imperialism” as well as “reflect on their own mistakes.”45

However, at the heart of this “democratization campaign” were the previously mentioned baojia elections and the reform of the JSGC. From the very beginning, the Chinese side was clearly critical of the fact that the JSGC continued to be led by the political and business elite that formed the leading group of the kaisha-ha clique. Charges concerning the JSGC’s close connection with the history of Japanese aggression in China started to appear on Rehabilitation Daily as early as October 1945, immediately after the formation of the JSGC.46 These criticisms were shared by many commoner settlers, who had a deep distrust of the JSGC because its members were largely identical to that of the elite-controlled wartime Shanghai Japanese Residents Association (Shanhai kyoryū mindan), which, in 1942, absorbed the commoner-based Japanese Federation of Street Unions (Shanhai Nihonjin kakuro rengōkai) and took over the latter’s resources and functions. Therefore, rather than being an agency of self-government, many Japanese viewed the JSGC not only as emblematic of long-standing social stratification, but also an unpleasant reminder of the wartime mobilization that placed them under tighter surveillance of the state.47 Under the intensely nationalistic context of postwar Shanghai, such views were reinforced by the fact that many Japanese settlers now sought to distance themselves from the institutions that were connected with the Japanese invasion of China. In her discussion of the tension between repatriates and homeland Japanese, Lori Watt points out that, by stressing the distinctiveness of the repatriates, homeland Japanese “placed a buffer between themselves and the Japanese imperial project.”48 The repatriates, on the other hand, responded by holding Japanese leaders and soldiers culpable for aggression while labeling themselves as victims rather than perpetrators of the war. In fact, as we can see in the case of Shanghai, for many who would be repatriated, the process of constructing their own victimhood started before, rather than after, their return to Japan. And the perennial separation between the elite and commoners provided a convenient basis for such rhetoric, although in most cases it was the commoners, rather than the elite, who had behaved more jealously and aggressively in securing Japanese privilege and suppressing Chinese nationalism during the prewar period.49

The JSGC, led by former ambassador Tsuchida Yutaka, responded to these criticisms in a number of ways. First, it exhorted the rich to refrain from conspicuous consumption and gambling, urging economy in food and other daily expenditures, and to dress modestly.50 In the meantime, the JSGC also organized donations to aid impoverished families. More importantly, in January 1946, the JSGC decided to create a new advisory body, “The Japanese Nationals Representative Committee” (Nikkyō daihyō i’inkai), whose members were to be elected by all male and female Japanese over 20 years old. The election was met with great enthusiasm, and 27,419 people voted, a remarkable turnout rate of 78.1 percent. As a result, this new committee consisted of many dochaku-ha settlers of good reputation. The most well-known was Uchiyama Kanzō, whose Uchiyama Bookstore was a famous site of Sino-Japanese literary exchange in the 20s and 30s with Lu Xun and Guo Moro among regular visitors. Other members included female activist Hamamoto Mashū and the radical Hoshino Yoshiki, who once called for a purge of all former government officials from the JSGC.51 Meanwhile, the Chinese side closely monitored the election, even praising it as “a great experiment of democratic politics by the Japanese awaiting repatriation, which will serve as a prototype for popular elections in postwar Japan.”52

In short, the JSGC played a vital role in the management of the concentration zone at least until early 1946, serving as the only formal channel through which the Japanese community could make their voices heard by the GMD authorities. Although established under GMD supervision, in many ways the JSGC resembled prewar Japanese settler organizations in providing Japanese residents with public services such as education and public health and negotiating with Chinese authorities. It struggled to retain control of a variety of resources and facilities previously held by Japanese. By the end of 1945, the shortage of medical supplies in the concentration zone became acute, as only six hospitals were permitted to continue treating Japanese patients. After several rounds of negotiation, the JSGC persuaded the SJNMO to reopen fifteen hospitals that had been operated by the Japanese.53 At the same time, the JSGC secured access to the Japanese public cemetery on Hengbin Road that was once managed by the Japanese Residents Association.54 Moreover, the JSGC regularly reported to the Shanghai police on criminal cases that involved Japanese victims and actively assisted in investigation.55

Before and after repatriation: the final days of Shanghai’s Japanese community

In early 1946, the GMD authorities were finally able to hasten the repatriation process with greater shipping capability supported by the Americans. All Japanese civilians remaining in Shanghai, with the exception of those whose service was sought by the Chinese authorities, were scheduled to be repatriated by May of that year. A vigorously debated issue concerned how many personal belongings repatriates would be allowed to carry. The GMD’s initial policy stipulated that each adult could carry up to 15 kilograms of baggage, explaining:

“When the Japanese first arrived Shanghai, they came with no more than one suitcase. All the wealth they accumulated ever since was gained through exploiting Chinese people under Japanese military authority. It is their fate to be repatriated, but their wealth belongs to China and thus ought to stay here. It is just right and proper to have them return with just one suitcase.”56

Viewed in this light, GMD policy unambiguously labelled all civilian repatriates as perpetrators of Japanese imperialism, the same rationale behind the GMD’s requisition of Japanese civilian assets as discussed above. In a sense, these policies ran counter to Chiang Kai-shek’s original idea of “differentiating the innocent Japanese people from the militarists.”

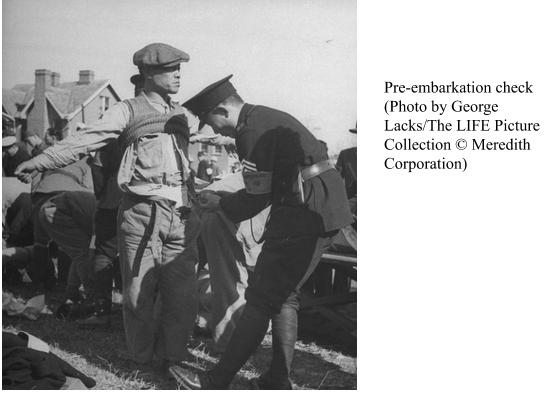

Unsurprisingly, the rigid limit on baggage caused great anxiety among repatriates about their situation after return to Japan. Under JSGC mediation, the GMD authorities agreed to double the weight allowance and to allow an extra five kilograms of food and cash up to the equivalent of 1000 Japanese yen per person.57 At the same time, repatriates used an array of strategies to cope with the limitation, for example, wearing as much of their finest clothing as possible—many with multiple layers of pants and underwear when going through the pre-embarkation check.58

However, the journey back home still involved immense frustration for many repatriates, as they were usually not notified of the exact date of departure until two or three days in advance. This ordeal of waiting is well exemplified by Tanaka Keiko’s recollection fifty years later.59 As mentioned before, Keiko’s family lost their business when the war ended. The ensuing emotional stress caused her mother’s paralysis. In the next six months, Keiko spent every day caring for her hospitalized mother. Although they were qualified for early repatriation, since Keiko’s mother was too sick to move on her own, they had to wait for a hospital ship coming from Japan. In March 1946, when there was finally news of an approaching hospital ship, Keiko quickly started to pack to be ready for boarding once it arrived. However, three weeks passed before they received the order to assemble at the wharf for pre-embarkation check. Arriving at the wharf, they were again disappointed to find that the exact date of the ship’s arrival was still unknown, and until the ship came they and several hundred others had to stay in a nearby warehouse. While waiting for an entire month, Keiko’s ill mother lay in a bed made of concrete covered only with a very thin mat. Her health deteriorated day by day, and in the end, she was barely able to eat. On May 1, two days after the ship finally departed, her mother died.

Although human tragedies were no small part of postwar repatriation, the deportation of Japanese civilians from Shanghai in early 1946 proceeded in a relatively efficient and swift fashion. By June, 127,000 people had returned to Japan, concluding the history of Shanghai as one of Japan’s largest overseas settlements in the modern era. Nevertheless, the Japanese presence in Shanghai continued. In mid-1946, the newly founded Remaining Japanese Support Society (Zanryū nikkyō sewakai) replaced the JSGC as the chief organization of the Japanese settler community. With the goal to “promote mutual aid and cement solidarity among our countrymen in Shanghai,” this new agency continued to perform functions such as providing emergency relief and running Japanese schools.60 As of March 1947, 1,501 Japanese civilians still lived in Shanghai, either as employees of private companies or the GMD government or as members of their families.61 The issue of their return to Japan would linger for years and was closely linked with the changing political circumstances. Bookseller Uchiyama Kanzō, for instance, was allowed permanent residence by the GMD authorities. However, when GMD rule of China was challenged by the Communists in late 1947, Uchiyama was deported for his well-known left-wing connections.62 Meanwhile, far more Japanese with valued professional skills were forced to stay by the GMD authorities and, later, the CCP government.63 Some Japanese volunteered to remain in Shanghai after the war. One example was Nishikawa Akiji, an experienced engineer who had worked for Toyota’s textile machinery factory in Shanghai for thirty years. After the war, he was “determined to devoted himself to realizing the self-sufficiency of China’s textile machinery.” For both the GMD and CCP authorities, Nishikawa fit perfectly the type of person they wanted to retain. Their repatriation would eventually take another decade of negotiation between the PRC and Japan.

Conclusion

Shortly after the war, the Allied powers started a massive project that sent 6.5 million overseas Japanese soldiers and civilians back to their home country. Hosting one of the largest and most developed Japanese overseas settlements at the time, Shanghai became an important site for the dismantling of the Japanese empire. However, in contrast to the demobilization and return of Japanese servicemen, the treatment and repatriation of civilians was not planned in advance. The initial weeks following the end of the war was a time of chaos and uncertainty for Japanese settlers in Shanghai. Despite GMD efforts to curb anti-Japanese sentiment and minimize Sino-Japanese contact, violence targeting Japanese citizens occasionally occurred. Nonetheless, many Japanese were able to protect themselves by mobilizing long-term connections with the local population, which, in turn, suggests that it was not the case that the local Japanese community was “hardly in touch with Chinese realities”64 as conventionally understood.

After the GMD takeover of Shanghai in September 1945, it adopted systematic rules to relocate Japanese civilians and regulate their activities, starting with the concentration zone and the baojia system. Despite strong American influence over the postwar reconfiguration of East Asian societies, the GMD authorities displayed no lack of initiative and determination in pursuing policies of their own concerning Japanese settlers. On one hand, they shared the American idea of repatriation of all Japanese civilians and were eager to expedite repatriation for both security and logistical reasons. On the other hand, they succeeded in retaining a significant portion of the Japanese legacy in the form of both requisitioned assets and skilled personnel. In addition, the GMD authorities preserved a large part of the prewar structure of the Japanese settler community to manage the concentration zone, which inadvertently empowered the Japanese to negotiate favorable treatment. Connected with this was the GMD’s campaign to educate and democratize the Japanese settler population. While this approach may have allowed the Japanese a certain degree of autonomy on the daily administration of the concentration zone, it categorically labeled all Japanese civilians as perpetrators of Japan’s colonial enterprise. The latter, along with the continuation of social and economic inequality within the settler society, drove many middle- and lower-class Japanese to distance themselves from the elite—whom they thought should be held responsible for Japanese aggression in China—and to emphasize their own victimhood under prewar social stratification as well as wartime mobilization and surveillance.

Another theme that looms large throughout is the fixation of ethnic-national categories; but the identification (and self-identification) of those who needed to go back to their “homeland” was sometimes full of tension. Whereas the GMD authorities’ concerns for social stability and public security underpinned the expansion of the definition of “Japanese” in postwar Shanghai, plenty of examples show how people attempted to exploit the flexibility of their identities or redefine them under new political and ideological circumstances. All in all, postwar repatriation unfolded in a way that was shaped by the continuous interplay between multiple parties, without being monopolized by any one of them. At the same time, there was remarkable variation in the human experiences related to the repatriation process. To understand these experiences requires taking into consideration both continuity and discontinuity between the prewar and postwar periods. In this sense, if the images and discourses surrounding repatriates constituted an essential part of how postwar Japanese society negotiated its memories of war and defeat, the first-hand experience of repatriates as the final human remnants of the Japanese colonial empire formed a bridge that spatially and temporally connected postwar Japan with its imperialistic past and the future of postwar Japan-China relations.

References

Brooks, Barbara J. Japan’s Imperial Diplomacy: Consuls, Treaty Ports, and War in China, 1895-1938. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2000.

Chen, Zu’en 陳祖恩. Shanghai Riqiao shehui shenghuo shi, 1868-1945 上海日僑社會生活史. Shanghai: Shanghai cishu chuban she, 2009.

———. Xunfang dongyang ren 尋訪東洋人. Shanghai: Shanghai shehui kexue yuan chuban she, 2007.

Dower, John W. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000.

Duus, Peter, Ramon H. Myers, and Mark R. Peattie, eds. The Japanese Informal Empire in China, 1895-1937. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Fogel, Joshua A. “Integrating into Chinese Society: A Comparison of the Japanese Communities of Shanghai and Harbin.” In Japan’s Competing Modernities: Issues in Culture and Democracy, 1900-1930, edited by Sharon A. Minichiello. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001.

———. “‘Shanghai-Japan’: The Japanese Residents’ Association of Shanghai.” The Journal of Asian Studies 59, no. 4 (November 2000): 927–50.

Fujita, Hiroyuki 藤田拓之. “Kokusai toshi Shanhai ni okeru Nihonjin kyoryūmin no ichi” 国際都市上海における日本人居留民の位置. Ritsumeikan gengo bunka kenkyū 21, no. 4 (March 2010): 121–34.

Gaizao Ribao 改造日報. Shanghai, 1945-46.

Heiwa kinen jigyō tokubetsu kikin 平和祈念事業特別基金. Kaigai hikiagesha ga kataritsugu rōku: hikiage hen海外引揚者が語り継ぐ労苦(引揚編). 20 vols. Tokyo: Heiwa kinen tenji shiryōkan. 1991- . https://www.heiwakinen.go.jp/library/shiryokan-heiwa/

Henriot, Christian. “‘Little Japan’ in Shanghai: An Insulated Community, 1885-1945.” In New Frontiers: Imperialism’s New Communities in East Asia, 1842-1953, edited by Robert A. Bickers and Christian Henriot. Manchester: Manchester university Press, 2012.

Igarashi, Yoshikuni. Homecomings: The Belated Return of Japan’s Lost Soldiers. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.

Katō, Yōko 加藤陽子. “Haisha no kikan: Chūgoku kara no fukuin, hikiage mondai no tenkai” 敗者の帰還:中国からの復員・引揚問題の展開. Kokusai seiji, no. 109 (May 1995): 110–125.

Kojima Shō小島勝 and Ma Honglin馬洪林, eds. Shanhai no Nihonjin shakai: senzen no bunka, shūkyo, kyōiku 上海の日本人社会:戦前の文化・宗教・教育. Tokyo: Ryokoku daigaku bukkyo bunka kenkyūsho, 1999.

McWilliam, Wayne C. Homeward Bound: Repatriation of Japanese from Korea after World War II. Hong Kong: Asian Research Service, 1988

Okazaki, Kaheita 岡崎嘉平太. Watakushi no kiroku : hisetsu haru no itaru o mukau 私の記録: 飛雪、春の到るを迎う. Tokyo: Tōhō shoten, 1979.

Ozawa, Masamoto 小沢正元. Uchiyama Kanzō den : Nitchū yūkō ni tsukushita idai na shomin 內山完造伝: 日中友好につくした偉大な庶民. Tokyo: Banchō shobō, 1972.

Satō, Ryō 佐藤量. “Sengō Chugoku ni okeru Nihonjin no hikiage to kensō” 戦後中国における日本人の引揚げと遣送. Ritsumeikan gengo bunka kenkyū 25, no. 1 (October 2013): 155–171.

Shanghai Municipal Archives 上海市檔案館 (SMA)

Shenbao 申報. Shanghai and Hankou, 1945-1946.

Takatsuna, Hirofumi 高綱博文. “Kokusai toshi” shanhai no naka no Nihonjin 「国際都市」上海の中の日本人. Tokyo: Kenbun shuppan, 2009.

———. Senji Shanhai戦時上海, 1937-1945. Tokyo: Kenbun shuppan, 2005.

Tō Onhaku ki’nenkai 湯恩伯記念会. Tō Onhaku shōgun: Nihon no tomo湯恩伯将軍 : 日本の友. Tokyo: Tō Onhaku kinenkai, 1954.

Uchiyama, Kanzō 内山完造. Kakōroku 花甲録. Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1960.

Watt, Lori. When Empire Comes Home: Repatriation and Reintegration in Postwar Japan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2009.

Wu, Zimei 吳子美, “Jizhongqu youji” 集中區遊記. In Minguo ribao, February 6, 1946.

Yokoyama, Hiroaki 横山宏章. Shanhai no Nihonjingai, Honkyū: mō hitotsu no Nagasaki 上海の日本人街・虹口:もう一つの長崎. Tokyo: Sairyūsha, 2017.

Zhao, Yanmin 趙彦民. “Sengō Chūgoku no zanryū Nihonjin seisaku” 戦後中国の残留日本人政策. Aichi Daigaku kokusai mondai kenkyū kiyō, no. 142 (December 2013): 97–128.

Notes

Kageyama Tetsu 影山澈, “Shanhai Nikkyō chūgakusei no shūsen nikki” 上海日僑中学生の終戦日記, in Kaigai hikiagesha ga kataritsugu rōku: hikiage hen海外引揚者が語り継ぐ労苦(引揚編) (KHGKR), Vol. 12, 265-268.

“Dui zaihua Riqiao Gu dashi guangbo pan lengjing chenzhuo renyin zizhong” 對在華日僑谷大使廣播盼冷靜沉著忍隱自重, Shenbao, August 16, 1945, 1.

See, for example, Koiwa, “Shanhai kara hikiage te,” in KHGKR, Vol. 13, 292; and Koike, “Watashi no ikizama!” in KHGKR, Vol. 15, 227.

See, for example, Christian Henriot, “‘Little Japan’ in Shanghai: An Insulated Community, 1885-1945,” in New Frontiers: Imperialism’s New Communities in East Asia, 1842-1953, ed. Robert A. Bickers and Christian, 146-169.

Henriot, “‘Little Japan’ in Shanghai,” 150-152; and Yokoyama Hiroaki 横山宏章, Shanhai no Nihonjingai, Honkyū: mō hitotsu no Nagasaki 上海の日本人街・虹口:もう一つの長崎, Chapter 2 & 5.

Initially, the Americans only had a vague notion that former Japanese colonies should remove Japanese civilians, and the repatriation focused on Japanese servicemen. But for a mixture of pragmatic and humanitarian reasons, the U.S. military soon concluded that civilian repatriation was necessary. Some evidence suggests that this was a personal decision by General Douglas MacArthur. See Watts, When Empire Comes Home, 40; and McWilliams, Homeward Bound, 9. The Chinese side also did not discuss civilian repatriation ither immediately after the war. But it had ample reasons to support the American initiative—security and logistics being the two main concerns.

According to the SJNMO’s survey in March 1946, 16 percent of the 35,130 requested not to be repatriated, with 65 percent of these respondents referring to “Sino-Japanese friendship” as a reason. See Gaizao ribao, March 17, 1946, 2.

Uchiyama Kanzō 内山完造, Kakōroku 花甲録, 367. At the height of the war in 1941 and 1942, the Japanese authorities in Shanghai made efforts to forge a stronger unity among the city’s Japanese population by centralizing the organizations of local Japanese settlers. In this process, the Japanese Residents’ Association, the consulate, and other elite bodies managed to completely co-opt the groups previously run by Native-Clique leaders in a much more independent manner, for example, the Japanese Federation of Street Unions. Meanwhile, Japanese residents joined a number of new organizations—such as the Total Strength Patriotic Association of Shanghai (Shanhai Sōryoku hōkoku kai)—that were founded to contribute to Japan’s war effort. Moreover, at Shanghai’s Japanese schools, nationalist education and military training were intensified. See Joshua Fogel, “‘Shanghai-Japan’: The Japanese Residents’ Association of Shanghai,” 937-941; and Takatsuna Hirofumi, Senji Shanhai戦時上海, 1937-1945,Chapter 1& 8.

For example, during the Shanghai Incident of 1932, Japanese residents of Hongkou and Zhabei actively assisted the military in fighting the Chinese army and “uncovering plainclothes Chinese soldiers,” whereas the Japanese diplomats on-site and big businesses were more inclined to defuse the tension and negotiate with the Chinese side. The same pattern could be seen throughout the 1920s when anti-Japanese sentiment grew quickly in Shanghai. See, for example, Takatsuna, ‘Kokusai toshi’ Shanhai no naka no Nihonjin, Chapter 3; Joshua Fogel, “‘Shanghai-Japan’: The Japanese Residents’ Association of Shanghai,” 934-937; Yokoyama, Shanhai no Nihonjingai, Chapter 6 & 7; and Barbara Brooks, Japan’s Imperial Diplomacy: Consuls, Treaty Ports, and War in China, 1895-1938, Chapter 3 & 4.

See Ozawa Masamoto 小沢正元, Uchiyama Kanzō den: Nitchū yūkō ni tsukushita idai na shomin 內山完造伝: 日中友好につくした偉大な庶民, 311-314.

Each child under 16 could carry up to 15 kilograms of baggage and 500 yen in cash. In reality, this weight limit was not strictly enforced. People were allowed to carry as much as they could at the time of boarding.