Abstract: Indigenous people are often depicted as helpless victims of the forces of eighteenth and nineteenth century colonial empire building: forces that were beyond their understanding or control. Focusing on the story of a mid-nineteenth century diplomatic mission by Sakhalin Ainu (Enchiw), this essay (the second of a two-part series), challenges that view, suggesting instead that, despite the enormous power imbalances that they faced, indigenous groups sometimes intervened energetically and strategically in the historical process going on around them, and had some impact on the outcome of these processes. In Part 2, we look at the Nayoro Ainu elder Setokurero’s intervention in imperial negotiations between Japan and Russia in the early 1850s, and consider what impact this may have had on the experiences of Sakhalin Ainu during the early phases of Russian and Japanese colonial rule in Sakhalin.

Keywords: Sakhalin; Sea of Okhotsk; Ainu; Japanese Empire; Russian Empire; indigenous people; Russo-Japanese relations.

This is Part 2. Part 1 – Traders and Travellers appeared in the November 15 issue.

Тhe Arrival of the Russians

In the summer of 1853, the Russians appeared in the Sakhalin village of Nayoro, in the person of Naval Lieutenant Dmitrii Ivanovich Orlov, accompanied by six companions, of whom five were indigenous Saha (Yakut) troops recruited by the Russians on the mainland.1 They may not have been the first Russians whom Nayoro villagers had encountered. Over the course of the past couple of decades, several Russian ships had been wrecked on the shores of Sakhalin, and at least three Russians had reportedly lived for years near the village of Mgach on the northwest coast, probably passing through Nayoro as they travelled south to trade with the Japanese.2 But, for Nayoro’s Ainu villagers, the size and formality of Orlov’s party must have been disconcerting; and it was, as it turned out, just one ripple from a very large new wave of Russian power which was expanding in many directions across the Asian continent.

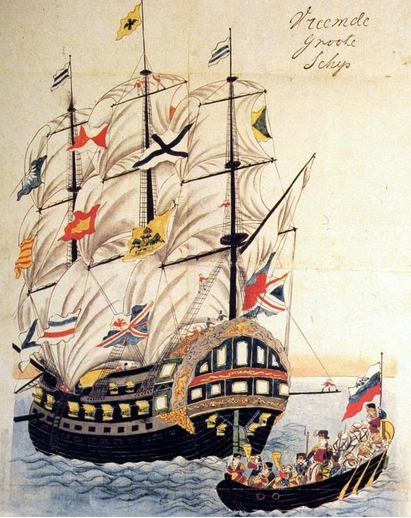

|

Yevfimii Putyatin’s Ship, the Pallada, in the Port of Nagasaki 1854, Artist Unknown (Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain) |

To the west, the imperial ambitions of Tsar Nicholas I were raising tensions with the Ottoman Empire, and just a few months after Orlov’s arrival in Nayoro, in October 1853, this would result in the outbreak of the Crimean War. Meanwhile, following hard on the heels of Matthew Perry, Russian Admiral Yevfimii Vasilyevich Putyatin had arrived in Nagasaki to press Japan to open its ports to Russia. Negotiations with the Japanese Shogunate were to drag on until February 1855, when Russia and Japan signed the Treaty of Shimoda, and during those negotiations a key sticking point was the location of the frontier between Japan and Russia in Sakhalin.3

|

The Changing Sino-Russian Border: Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries (Source: Central Intelligence Agency map, 1960, Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C. 20540-4650 USA DIGITAL ID g7822m ct002999 ) Public domain. Edited to replace place name “USSR” with place name “Russia” |

Relations between the Russian and Chinese empires were also once more in a state of flux, as Russia sought to overturn the Treaty of Nerchinsk and gain control of the crucial strip of coast from the mouth of the Amur to the northern border of Korea. To press these claims, Tsar Nicholas had (after some hesitation) sanctioned a major expedition under the leadership of Captain (later Rear Admiral) Gennadii Ivanovich Nevelskoi, which arrived in the Lower Amur region in 1849 and established the Russian settlement of Nikolaevsk near the mouth of the river in 1850.4 From then until 1855, Nevelskoi dispatched a series of smaller parties to investigate the situation on Sakhalin Island and determine whether Russia could lay claim to the island. Orlov’s was the second of these. The first consisted of just two people: a young military officer, Nikolai Konstantovich Boshnyak, and his Amur Nivkh guide Pozvein, who travelled to the northwest coast of Sakhalin and along the River Tym in 1852. Boshnyak’s expedition was poorly prepared and sparsely supplied5, and he returned to the Amur weak and exhausted after six weeks.

Dmitrii Orlov had been commissioned to ‘describe the western coast of the island from 51° north to its southern tip and to scout out the position of the Japanese possessions in Aniwa Bay’.6 In true imperial fashion, on arrival in Sakhalin he raised the Russian flag near an Ainu village a little north of Nayoro. But when he reached Nayoro on a stormy summer’s night, he encountered the local Setokurero (whose background we explored in Part 1 of this essay). Setokurero had just returned from a trip to the southern part of Sakhalin, and he warned Orlov that the Japanese had heard of the Russians’ arrival, and were planning to ambush them.7 He also brought tidings of the arrival of a separate Russian expedition, headed by Nikolai Busse, which had just set up camp next to the Japanese trading post at Kushunkotan. Setokurero then offered Orlov the services of one of his five adult sons, Kanchomante8, who could guide him to safety through the forest. With Setokurero’s son as their guide, Orlov and his party fled inland, leaving much of their equipment behind in Nayoro. They crossed the island to the east coast, from where they made their way south to join Busse at the makeshift fort which he had set up at Kushunkotan and named ‘Fort Muravyov’ (Muravyovskii Post).9

Nikolai Busse’s expedition to Kushunkotan was on a very different scale from Boshnyak’s and Orlov’s ventures. He arrived in Sakhalin in early September with a party of about sixty people, and instructions to build a fortified encampment a short distance from the Japanese settlement of Kushunkotan. This was not a violent invasion, though. The Russians and Japanese were wary of one another and were conscious of the sensitive negotiations between their nations going on in Japan. They therefore spent almost nine months living in uneasy but generally peaceful proximity, until Russia’s worsening fortunes in the Crimean War led to the temporary abandonment of Fort Muravyov at the end of May 1854. Important parts of the everyday relationship between the Japanese and their new Russian neighbours were looked after by prominent local Ainu, who were entrusted with the task of managing the Japanese storehouses in Kushunkotan during the winter months, while most of the Japanese traders, officials and fishermen retreated to the slightly less hostile climate of Hokkaido.10

Kanchomante, Setokurero’s son, having arrived in Kushunkotan with Orlov and his expedition, also stayed on there, and helped to guide Busse and other Russians along the lower reaches of the nearby Susuya River, a crucial waterway extending into the fertile valleys of southern Sakhalin.11 Setokurero, in other words, was carefully preparing his own intervention in the negotiations going on between the Japanese and the Russians, first by scouting out the activities of the Russians himself, and then by strategically placing his son as their guide – a position which would give him further inside intelligence about the people with whom Setokurero hoped to negotiate.

The 1853‒1854 Russian occupation of Fort Muravyov was enlivened by the fact that Major Busse and his second-in-command, Lieutenant Nikolai Vasilyevich Rudanovskii, heartily loathed one another, and spent as much time as possible avoiding each other’s company. In order to rid himself of the presence of Rudanovskii, whom he variously described as being rude, impatient, stupid and ‘real poison’12, Busse did his best to encourage his deputy to travel around the island mapping its territory, and it was on one of these expeditions in December 1853 that Rudanovskii encountered Setokurero and his entourage of twenty or so other indigenous elders as they travelled southward on their mission to Kushunkotan with their convoy of heavily laden sleighs: they were bringing with them, perhaps as a goodwill gesture towards the Russians, the equipment and supplies that Dmitrii Orlov had left behind in their village when he fled from Nayoro a few months earlier.13

Learning that a Russian officer was in the neighbourhood of the village where he and his companions were staying, Setokurero went to visit Rudanovskii at the Ainu house where he had taken shelter for the night. Rudanovskii was accompanied by Ainu guides and assistants who must have been able to provide some form of interpretation, because he managed to have a conversation with Setokurero which went on late into the night, and – despite his generally condescending attitude towards the ‘natives’ – he was impressed by the Ainu elder’s ‘natural intelligence’.14 Setokurero, the Russian recorded, ‘told me of all sorts of injustices and insults from the Japanese’ to which the Ainu were subjected, and repeatedly uttered the words ‘“Sisam sumki [sunke], Sisam sumki”, that is, “the Japanese are all lying”’. The Ainu elder then explained to Rudanovskii that he was going to Kushunkotan to tell the Russians that the Ainu were willing to throw in their lot with the Russians and, if serious conflict ensured, they would not take up arms on the Japanese side.15

But Rudanovskii, Busse and the other Russian officers had been firmly instructed by their superiors that they were not to provoke the Japanese by interfering in their power relationship with the Ainu. So Rudanovskii responded by telling Setokurero that he and his fellow countrymen had come to this land to ‘live in peace with the Japanese’, and that, when they reached Kushunkotan, the Ainu group would be able to witness for themselves the amicable relationship between Japanese and Russians. This seems to have caught Setokurero by surprise, for he ‘jumped up from his seat and asked several times, “Russkii i Sisam uneno, Russkii i Sisam uneno?”’ which Rudanovskii interprets as meaning ‘do the Russians and the Japanese get along fine?’16. The last word of Setokurero’s question, though, clearly seems to be the Sakhalin Ainu word ‘unino’ – ‘equal’ or ‘the same’17 – which would give the whole sentence a rather different meaning. The conversation then moved on to trade, as Setokurero questioned Rudanovskii about the items that could be purchased from the Russians, expressing interest in ‘silver earrings, sabres and other requisites that they cherish’.18 Setokurero also asked about the availability of alcohol, which may have meant (as Rudanovskii clearly assumed) that he liked a drop himself, but which more likely reflected the fact that saké was a valuable trade item and an essential gift to the gods used in all Ainu religious ceremonies, but (even given a supply of the necessary ingredients) was difficult to brew in the cold Sakhalin climate.

After their conversation, Rudanovskii penned a letter of introduction addressed to Busse and gave it to Setokurero to take with him on his mission. According to Busse, this letter ‘explained the purpose of the trip by Setokurero… This goal is the same for all the Ainu guests who came to me ‒ to receive gifts.’19 Those words set the tone for everything that was to follow.

A Moment of General Silence: Setokurero in Kushunkotan

On his arrival in Kushunkotan, Setokurero made contact with a Cossack named Dyachkov, the one member of the Russian occupying force who had started to learn the Ainu language, and through him arranged an audience with Nikolai Busse. The encounter took place at Busse’s residence in the Russian fort, and is vividly and tellingly recorded, from the Russian viewpoint, in Busse’s memoirs. The scene of his meeting with the assembled Ainu, Busse wrote, ‘was very similar to the pictures representing the arrival of Europeans in America.’ Like the Conquistadors before him, Busse found himself surrounded by a sea of unfamiliar faces, dealing with people whose language he did not speak and whose customs he did not understand. He gazed at his visitors intently, remarking on their ‘handsome healthy faces, thick hair, and direct open gaze’ which, he felt, immediately distinguished them from the Ainu of the area around Kushuntotan, whose bodies were more often marked by the effects of harsh conditions in the Japanese fisheries and the impact of imported diseases. Busse continues:

After the first greetings, which, as is well known, consist of bowing their heads and raising their hands, the meal began with rice, fish, raisins, wine and tea. The Janchin20 [Setukurero] made a long speech, and after him another Ainu began; although some seemed unhappy with his speech, he continued. From these speeches, I and my translator, the Cossack Dyachkov, could only understand that it was about the Japanese, about the arrival of their Janchin and about the arrival of the Russians on Sakhalin.21

The problem was, of course, that Dyachkov, despite his commendable efforts, had only been learning Ainu for a few months, and clearly had no more than a basic conversational grasp of the language – not nearly adequate to interpret the Ainu oratory which they were hearing. Even Busse himself seems to have been conscious that he was missing something important: ‘I was sorry that I could not understand Setokurero’s speech. Judging by his intelligent eyes and the liveliness of his gestures, this speech must have been interesting and clever.’22 But it was not to be, though Busse’s comments do give an interesting indication of possible differences of opinion within the Ainu delegation – an indication consistent with his other meetings with local Ainu, who expressed a range of perspectives on the political situation, some more supportive of the Japanese presence and some more friendly towards the Russians.

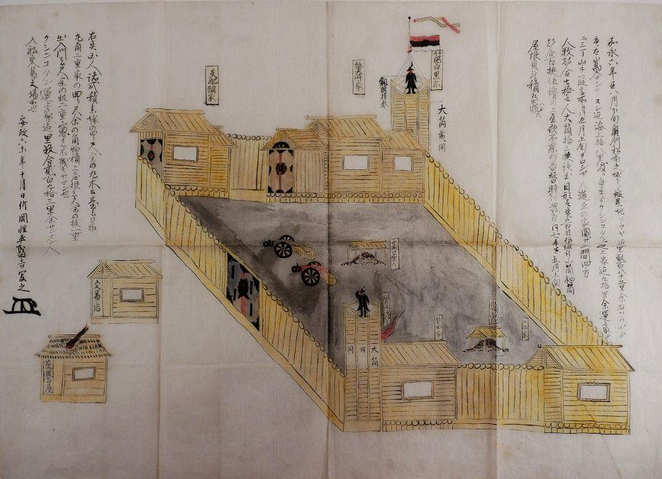

|

A Japanese depiction of the Russian Fort Muravyov (copied in 1859 from an original image drawn in 1853; Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University) |

‘After the speeches,’ Busse tells us ‘there was a moment of general silence, and it was noticeable that my guests were awaiting something.’ We can almost hear that silence today – that moment when, having set out their case with all the eloquence at their disposal, the indigenous people await the reply from the foreign intruder. This, surely, was the moment for Busse to respond to the impassioned case that he had just heard: to react to the accounts of cruelty in the fisheries; to show that he understood the history of Ainu connections to surrounding countries; to explain Russia’s long-term goals in the region; or maybe just to answer the question, ‘are the Russians and Japanese the same?’ But Busse, of course, had prepared his response before Setokurero had even opened his mouth. ‘It was not difficult for me to guess that what they were waiting for was gifts. I ordered these to be brought in and started distributing them. Setokurero received a hand-made length of red thin cloth and a large woollen shawl, the other elders each received a blanket and a small silk scarf, and finally the Ainu who had no claim to official status, a sailor’s blue shirt.’

Busse was, by and large, a careful observer, and had developed quite friendly relations with some of the Ainu in and around Kushunkotan. He had visited their houses, heard stories about life in the fisheries, and even heard the voices of those who ‘often say “Karafuto Ainu Kotan, Sisam Kotan Karafuto isam”, that is “Sakhalin is the land of the Ainu. There is no Japanese land on Sakhalin”’.23 But he had his instructions, which were to leave relations between the Japanese and the Ainu undisturbed, and he lived in a world where, as in the first arrival of Europeans in the Americas, the relationship with the indigenous people was mediated by things rather than by words. Busse had indeed spent a significant part of his time on Sakhalin trying hard to work out just which things were the most appropriate ones to use in dealings with the Ainu: eventually, through trial and error, discovering that trinkets like shiny buttons were less acceptable than thin red cloth and shawls of the sort that he presented to Setokurero.24

Things, after all, are so very much easier to give than attention or respect or the recognition of rights. So, it was only after satisfying the visitors’ presumed desire for gifts that Busse ‘told Setokurero that I was very glad to see him and that I was pleased to know that he loved the Russians, that we had come to the land of the Ainu with the intention to live amicably with them, but that we did not want to quarrel with the Japanese, with whose emperor we were now conducting negotiations.’ Until the Russian status in the region was established, Busse instructed the Ainu ‘to continue working for the Japanese’.25

After the meeting with Busse, Setokurero also went to speak to the Japanese, who clearly knew a good deal more about his background than the Russians did. The Cossack interpreter Dyachkov also attended that meeting and reported to Busse that ‘having put Setokurero in a place of honour and treated him to [rice] wine, the Japanese listened with signs of respect to his speech, in which he advised them not to treat the Ainu badly now that the Russians had come to their land. The Japanese also gave the Ainu rice and vodka [probably shōchū].’26 So, Busse concluded, ‘the reception given to Setokurero should have satisfied him.’ But it did not. Setokurero kept coming back and kept receiving the same response. During every visit, he would be given alcohol and gifts, but no satisfactory answers to his demands and questions. On one occasion he also brought the Amur Nivkh member of his delegation to visit the Japanese, who reacted angrily because Nivkh were only supposed to interact with Japanese via the formal tribute process.27

On the last day of his stay in Kushunkotan, Setokurero visited Busse to say farewell, and was treated with more alcohol and presents for himself and his sons. He then went to the Japanese official quarters where he was immediately offered more saké. Clearly frustrated and angry and (according to Busse) drunk, Setokurero then lost his temper and berated the assembled Japanese for their treatment of the Ainu, demanding (according to Japanese sources) that Japanese fishery overseers who remained on Sakhalin should depart for Hokkaido when spring came.28 At this point, one of the Japanese officials, Maruyama Chūsuke, who was also reportedly drunk, struck the Ainu elder on the head with a pair of iron tongs, drawing blood.29 A group of Ainu gathered, and the situation became tense, but eventually calmer heads intervened. Setokurero was taken away to lie down and was given yet more gifts by the Japanese as a solatium. The Russians also intervened in an effort to smooth the situation, and fortunately no serious injury had been inflicted. The following day, with his head bandaged, Setokurero was ready to set off on his delayed journey home, telling Busse (with remarkable forbearance) that ‘the blow on the head had been beneficial to him.’30

Busse (unlike Maruyama) was polite to his Ainu visitors and ever generous with food, drink and gifts. But in political terms, the indigenous people of Sakhalin were, from his point of view, just an unwelcome obstacle that complicated the real task at hand: creating an advantageous modus vivendi with the Japanese Empire. His one-sentence summation of the Ainu elder’s mission was, ‘thus ended the visit of Setokurero, a visit which clearly showed that the Ainu would always be the cause of contention with the Japanese.’31

Consequences: Ainu Diplomacy and Japanese Policies

Setokurero’s diplomacy could be interpreted as having ended in a mixture of tragedy and farce; but that would be too simple a conclusion. His efforts at persuasion failed to have any fundamental effect on the imperial negotiations between the Russians and Japanese. These culminated in a decision, incorporated into the 1855 Treaty of Shimoda, that the two countries would have joint sovereignty over Sakhalin. But there are reasons to think, all the same, that Setokurero’s mission may have had a tangible impact on the way in which colonialism was exercised in Sakhalin.

The temporary Russian occupation of Kushunkotan had deeply alarmed the Japanese government, and the border negotiations with Russia heightened their awareness of the strategic importance of Sakhalin. As a result, the Shogunate dispatched a large contingent of officials to the island to report on conditions on the ground. The study team, consisting of about 150 officials with numerous Ainu guides and porters, travelled through Hokkaido and arrived in Sakhalin in June 1854 just after the departure of Busse and his companions. They remained there for about a month. The team was commissioned to gather the information needed both to determine the location of the border with Russia and to enable the Shogunate to resume direct control of the region from Matsumae Domain. Its members also distributed gifts to local Ainu, including special rewards to Ainu who had helped to protect Japanese property in Kushunkotan during the Russian occupation.

But another particularly important task was to investigate reports which had reached the Shogunate about Ainu accusations of the mistreatment of indigenous workers in the Japanese-run fisheries.32 The mission’s key members were Hori Toshitada (1818‒1860) and Muragaki Norimasa (1813‒1880), both significant figures in mid-19th century Japanese diplomacy. Hori was later to be responsible for Japanese negotiations with Prussia, but committed ritual suicide because of criticisms of his work as a negotiator, while Muragaki became one of the first Japanese officials to visit the United States, and on his return to Japan succeeded Hori as chief negotiator with Prussia.33

The team members dispersed to various parts of the southern half of Sakhalin to collect information, and one official, Suzuki Shigehisa, travelled to Nayoro to meet Setokurero. He arrived to find the elder absent on business, but Setokurero’s wife treated Suzuki to a meal of broiled trout and shellfish, and he sat talking with the couple’s son and other members of the household until Setokurero put in an appearance.34 The Nayoro elder then produced his treasure box and showed Suzuki the family collection of Manchu and Chinese documents, as well as carefully preserved letters left with the them by various Japanese officials over the past six decades, which the Japanese official carefully copied into his diary. Suzuki had clearly read earlier Japanese travel accounts of Karafuto, for he asked if he could see Yōchite’s tomb. His diary records that he was disappointed to hear that this was now decayed and had more or less disappeared.35 Muragaki Norimasa also held a meeting with Setokurero, whom he described as healthy, powerful and an eloquent speaker, and as having ‘deep inborn wiliness’.36

|

Japanese Official Suzuki Shigehisa Crossing a River with the Help of Sakhalin Ainu during his Inspection of Villages in the Southern Half of the Island in 1854 (Source: Suzuki Shigehisa, ed. Matsuura Takeshirō, Karafuto Nikki, Part 1, 1860, p. 22, National Diet Library) |

The reports and memoranda that the mission submitted to the Shogun’s chief advisors contained scathing criticisms of the treatment of Ainu by Japanese fishery managers and workers, as well as practical recommendations for improvements. The fishery overseers were described as obtaining goods from Ainu by deception, tearing indigenous families apart and stealing Ainu women.37 As historian Hiwa Mizuki points out, this righteous indignation had an ulterior motive: it provided ammunition which enabled the Shogunate to condemn Matsumae Domain’s failure to protect the Ainu population, thus justifying its own decision to re-impose direct Shogunal control over Ainu society. The condemnation of conditions in the fisheries also drew on older Shogunal stereotypes of Japanese fishery workers in the region as brutal and uncouth, and of the Ainu as helpless and ignorant people to be ‘protected’.38

But, as Hiwa also points out, the language of Hori and Muragaki’s reports marks ‘an important change from the pre-existing images of the Ainu’; and Hiwa highlights this change by citing the officials’ comments about Setokurero, who figured significantly in their reports.39 As Hori and Muragaki wrote, Setokurero was a person with a strong and distinctive personality, and from now on, careful consideration would have to be given to the best way of dealing with him. Because of his influence in the areas still beyond the reach of Japanese authority, though, they had some hopes that he could be won over to their side through concessions and benevolence, and that the Nayoro elder could thus become an asset in Japanese attempts to control the border region. The Japanese officials, in short, were forced for the first time, through their direct encounters with Setokurero and other Ainu elders in the region, to recognise the Ainu as active interlocutors with their own opinions on matters such as the evils of the fishery system.

These reflections do not always seem to have been effectively communicated to Japanese functionaries in Sakhalin itself. When Russian officer Nikolai Rudanovskii returned to the island in 1857, his first port of call was Setokurero’s house in Nayoro, but this time he found the Nayoro elder unwilling to help him, because (as Setokurero told his Russian visitor) some unnamed Japanese people had warned him that if he ever cooperated with the Russians again, the Japanese would ‘chop off his head and take them (pointing at his wives)’.40 Not long after, though, the Japanese authorities did indeed attempt a more conciliatory approach, amongst other things, by presenting Setokurero with a sword and later awarding him and his family a pension. In 1862, they also officially recognised his son Kanchomante as his successor.41

More importantly, the Shogunate made quite far-reaching efforts to control and reform the excesses in the fisheries. Authority over the Sakhalin fisheries was removed from the hands of the licenced merchants and transferred to Shogunal officers, who took charge of payments to Ainu workers and implemented a new policy of distributing alms to sick and elderly Ainu, nursing mothers and the bereaved in the fishery districts.42 This, as Hiwa argues, marked a shift from an official approach which tended to dismiss the Ainu as ignorant, incomprehensible and uncomprehending, towards a new ‘humane’ ideology (jinsei ideorogī) that sought to prevent Ainu resistance to colonial expansion through welfare and social improvement measures. The new policy, of course, went only a small way towards improving life for the Ainu labourers, and was combined with redoubled efforts to expand the fisheries northward, and to assimilate the Ainu into Japanese society.43 But (as we shall see) there are intriguing indications, not only that the reforms were important to Sakhalin Ainu themselves, but also that Ainu communities learnt lasting political lessons from the experiences of the early 1850s.

In a diplomatic world which left no place at the table for indigenous people, Setokurero had managed to make his voice heard because of his family history and his sheer force of personality, and because, as in many places, the colonizers were so deeply dependent upon those they colonized. They needed not only their labour but also their contacts and managerial skills and, above all, their knowledge of geography, landscape and environment. While Setokurero and his delegation had been in Kushunkotan in 1853, for example, Rudanovskii had been exploring Sakhalin by crossing over the central ridge of the island from the east coast to Nayoro. He could do this with unexpected speed and ease, because he was following a route which had been carefully explained to him by Setokurero: indeed, he was literally moving along the track cleared and smoothed for him by the Ainu elder’s large convoy of dog sledges. As Rudanovskii noted in his journal, ‘Setokurero and his fifteen sleighs had paved a most beautiful road for us.’44

|

Map of Southern Sakhalin Based on the 1853, 1854 and 1857 Expeditions of N. V. Rudanovskii and D. I. Orlov, with the Assistance of Konoskovani and Others. (State Historical Archives of the Sakhalin Region) |

In Nayoro, Rudanovskii met one of Seturokero’s wives45 (who originated from Taraika on the east coast of the island) and her brother, and also another Nayoro villager whose name he transcribes as ‘Konoskovani’. This man helped Rudanovskii draw a map of the west coast of Sakhalin from Nayoro to the southern tip of the island. The Russian observed that Konoskovani described the coast to him in meticulous detail and commented that ‘this was a rare example amongst the Ainu of someone knowing by memory places so far away from his home.’46 In fact, unbeknownst to Rudanovskii, Sakhalin Ainu had been the source of other major geographical ‘discoveries’ made by earlier generations of European explorers of Sakhalin, most notably Jean-François Galaup de la Pérouse’s mapping of sections of the island in the 1780s.47

Rudanovskii, went on to become renowned as a pioneering cartographer of the region. Despite Setokurero’s understandable caution about helping Rudanovskii on his second visit to Sakhalin in 1857, the Nayoro elder did in the end play an important part on this occasion too. The purpose of Rudanovskii’s mission this time was to negotiate further with the Japanese about the areas of Sakhalin that would be occupied by Japanese and Russians under the new arrangements for joint sovereignty. But the Japanese had no official buildings this far north, and so they and Rudanovskii ended up holding their key negotiations about their division of spoils on Sakhalin seated around the hearth of the Setokurero family home.48

Setokurero was now well into old age and soon to retire from his official role, but he remained healthy and active for at least another decade. The Russian geologist and botanist Carl Friedrich Schmidt (also known as Fyodor Bogdanovich Shmidt), on his travels through Sakhalin in 1860, ‘met one of the most respected Ainus, the old man Ssetakurero, who was also recognised as an Ainu elder by the Japanese by being given a sword. He still kept with him a letter written in the Manchu language, which his father had once received on a tribute trip to Ssan-ssin on the Sungari from the Manchu authorities, and by which he was appointed as an elder of the Ainu’.49 And when the doctor and linguist Mikhail Mikhailovich Dobrotvorskii lived on the island from 1867 to 1872 and compiled the first published Ainu-Russian dictionary, he observed that, despite the many health challenges faced by the indigenous people, he had met a number of Ainu centenarians. One of these, he wrote, was ‘Setokurero (who had once received a document from the Manchus, perhaps for ruling the island)’.50 Dobrotvorskii’s estimate of Setokurero’s age may have been an exaggeration and his description of the document a little amiss, but it is clear that the Nayoro elder was by then very venerable indeed.

But by the 1860s, the power politics of the region was already starting to unpick the delicately intertwined threads of Sakhalin’s ethnic and cultural diversity. Japanese political claims to the island were based on the assertion that the Ainu had been Japanese subjects from time immemorial, and this claim gave both Japanese and Russians an incentive to demark and define a geographical border between Ainu and other ethnic groups. Population surveys from the late 1860s show that the Ainu who had once lived side-by-side with Nivkh in Porokotan had been persuaded or forced to move to predominantly Ainu areas further south51; and that was just the start of a whole series of population movements, many of them involuntary, which would change the face of the island over the following decades.

In 1875, the Japanese relinquished their claim to Sakhalin in return for control over the Kurile Island chain, and at that time over a third of the Ainu population of Sakhalin (almost entirely from the southernmost regions) was persuaded to relocate to Hokkaido – a disastrous move which resulted in the death of around half the migrants in epidemics. Even though most of the survivors later returned to Sakhalin, epidemics continued to ravage the population, and after the re-division of the island between Japan and Russia following the Russo-Japanese War of 1904‒1905, indigenous people on both sides of the border were relocated into ‘strategic villages’ where they could be more thoroughly subjected to colonial modernisation and assimilation policies.

Conclusions: Sakhalin Ainu as Actors in International History

Even in these harsh times, Sakhalin Ainu continued to raise their voices in protest, drawing on traditions which echo Setokurero’s mid-19th century mission. Writing in 1904, on the eve of the Russo-Japanese War, the Polish ethnographer Bronislaw Piłsudski noted how Ainu who were mistreated by local settlers would often try to lodge protests with higher Russian authorities, on one occasion even successfully petitioning the visiting Governor General of Khabarovsk for protection of their fishing rights around the east coast village of Sakayama. This approach, Piłsudski argued, had its roots in Ainu experiences from the time of Matsumae Domain and the Shogunate, when ‘the Far East began to be more frequently visited by Europeans, and [therefore] the terrified princely court of Matsumae decided in good earnest that it was necessary to change its attitude of indifference to the enslaved Ainu and to improve gradually with an authoritarian hand their oppressive situation with the aim of winning them over to its side’.52 Although Piłsudski (who was not particularly expert in Japanese history) refers here to Matsumae rather than the Shogunate, his description fits the situation of 1853‒1854 so perfectly that it is hard to believe that he was not listening to Ainu memories of that time. Ainu protest techniques, he writes, reflect

the historically conditioned point of view according to which a higher authority is more just and attentive to petitioners than the lower-rank authority accessible nearby. Thus the Ainu frequently recall that in the times of strict dependence [on the Japanese] they suffered much from the local managers of the industries [i.e. the fisheries] but every visit of a ship from Hokkaido with high ranking officials on board, who came to listen to their complaints, was followed by a whole series of gradual improvements.53

Despite this history of resistance, by the 1920s, the Ainu community of Nayoro had been wiped off the map, and Setokurero’s story had been written out of Sakhalin’s history. The indigenous people of Sakhalin came to be viewed as objects of anthropological enquiry, not as actors in history. If their names appeared in the history books at all, they were recognised only as bit-players on the fringes of the drama played out between the empires – the eternal Rosenkrantzes and Guildensterns of history54, as it were. A fleeting mention of Yōchite appears here; a glimpse of Setokurero there55 – but never as central figures in the story; and so the story in which they were central figures vanished, too. And of course, Setokurero and his family were far from being the only ones. There are many other names and stories still to be recovered from the historical record, as well as the many thousands more who also played crucial roles, but whose names have vanished forever.

Bronislaw Piłsudski, who witnessed Ainu struggles to resist the destructive forces of colonialism, also recorded a rich collection of historical and mythical tales, songs and prayers from the indigenous people of Sakhalin. One of these is a prayer spoken by Ainu walking along the old trade route which linked the east coast of the island to the trading markets that once flourished along the River Tym. By this time, Russian penal colonies were encroaching ever deeper into the forests on the upper reaches of the Tym, and the trade between Ainu and the people to their north and west had almost vanished. Many of the areas where small settlements had once stood were now deserted. The prayer which Piłsudski recorded is a haunting lament for the loss of that world: the destruction of independence, the expropriation of territory, the separation of peoples from one another, the severing of trade routes, the suppression of culture and memory, the tearing apart of a whole web of indigenous economic and cultural connections; but it is also the prayer of people determined to survive:

Now I walk alone on the forest route along which my ancestors used to walk.

It is the route which they used to walk to visit one another.

But now all those ancestors left our land abandoned.

Now only Russians are ruling here and they use me as their servant.

So, my ancestors’ guardian deities, do protect me as I am walking here…

Having said this, I shall be thinking that the people who have seized our homeland consist also of human beings.

Thus, carrying you, [guardian] spirits on my back, only on you I pin my hopes when I am walking in this forest area among your trees…

On my way,… if you direct [the Russians’] thoughts away from me, I shall go on walking without fear.

I shall then be walking in a lucky mood.

Although I am walking alone, pinning my hopes on good deities, what could make me fear!

Having just received the spirit of bravery from the [guardian] deities, I shall go on walking.56

Notes

Busse, Ostrov Sakhalin i Ekspeditsiya 1853-1854 gg, St. Petersburg, F. S. Sushchinhskii, 1872, p. 34.

Russian officer N. K. Boshnyak recorded the following account given to him by Sakhalin Nivkh in 1852: ‘Constantly inquiring whether there were Russians who had settled somewhere on the island, I found out in the village of Tangi, the following: 35 or 40 years ago, on the eastern coast of the island and just near the village of Ngabi, a ship was wrecked; The surviving crew lived for a long time in the said village, built a house for themselves, and after a while a ship. On this vessel, the unknown people passed the La Perouse Strait and near the village of Mgach and again suffered a wreck, and only one person, called Kemts, was saved. Shortly after this incident, two Russians, Vasily and Nikita, arrived from the Amur. They joined Kemts and built a house for themselves in the village of Mgach, led a life like ordinary industrial Gilyaks, hunted fur-bearing animals and went to bargain with the Manchus and the Japanese’; Nikolai Konstantovich Boshnyak, ‘Ekspeditsiya v Priamurskii Krai: Ekspeditsiya na Sakhalin s 20 Fevralya do 3 Aprelya 1852 Goda’, Morskoi Sbornik, no. 7, 1858, pp. 179-194.

Akizuki Toshiyuki, Nichiro Kankei to Saharin-tō: Bakumatsu Meiji Shoki no Ryōdo Mondai, Tokyo, Chikuma Shobō, 1994.

See S. C. M. Paine, Imperial Rivals: Russia, China and their Disputed Frontier, Armonk NY, M. E. Sharpe, 1996, pp. 37‒39; E. G. Ravenstein, The Russians on the Amur: Its Discovery, Conquest and Colonisation, London, Trübner and Co, 1861, pp. 116‒117.

Boshnyak wrote that the sum total of his provisions consisted of ‘a sled of dogs, 35 days’ worth of biscuits, tea and sugar, a small hand compass, and most importantly – a crucifix belonging to Captain Nevelskoy and encouragement that if there is a biscuit to satisfy hunger and a mug of water, drink, and then all will be possible with God’s help’; Boshnyak, ‘Ekspeditsiya v Priamurskii Krai’.

Busse, who heard this story from one of Orlov’s Saha companions and recorded it in his journal, does not name Setokurero as the source of this information, simply saying that it came from an ‘elderly Ainu’ who had recently come from the south”, but the explanation in Rudanovskii’s journal makes clear that the ‘elderly Ainu’ was Setokurero, and the son was Kanchomante; see Busse, Ostrov Sakhalin, p. 35; Rudanovskii, ‘“Poezdki moi po Ostrovu Sakhalinu”’ p. 144.

His name is also sometimes given as ‘Kanchomanke’ or, by Rudanovskii, as ‘Kanchiomangin’, but appears as ‘Kanchomante’ in the official Japanese documents of the day.

Busse, Ostrov Sakhalin, p. 34; Rudanovskii, ‘“Poezdki moi po Ostrovu Sakhaliny”’, p. 144; see also Akizuki, Nichiro Kankei to Saharintō, p. 112.

See, for example, Busse, Ostrov Sakhalin, p. 32. In the winter of 1853, there were just 47 Japanese people in Kushunkotan and the surrounding area – see Nikolai Busse, trans. and ed. Akizuki Toshiyuki, Saharintō Senryō Nikki 1853‒1854: Roshiajin ga Mita Nihonjin to Ainu, Tokyo, Heibonsha, 2003, pp. 6‒40, citation from pp. 21‒22.

(ed. I. A Samarin), ‘“Poezdki moi po Ostrovu Sakhalinu Ya Delal Osen’yu i Zimoyu”: Otchyoty Leitenata N. V. Rudanovskovo 1853‒1854 gg.’, reprinted in Vestnik Sakhalinskovo Muzeya, no. 10, 2002, pp. 137‒166’, p. 144.

Mikhailovich Dobrotvorskii, Ainsko-Russkii Slovar’, Kazan, Universiteskaya Tipografiya, 1876, p. 370.

The Russians commonly referred to Ainu elders and Japanese functionaries as ‘janchin’, derived from the Manchu word for ‘official’.

Hiwa, Jinsei Ideorogī, pp. 33‒34; see also Suzuki Naoko, ‘Japanese-German Mutual Perceptions in the 1860s and 1870s: The Eulenberg and Bunkyū Missions’, in Sven Saaler, Kudō Akira and Tajima Nobuo, Mutual Perceptions and Images in Japanese-German Relations, Leiden, Brill, 2017, pp. 89‒109, citation from p. 98.

Suzuki Shigehisa, ed. Matsuura Takeshirō, Kōin Karafuto Nikki, (1860) National Archives of Japan, search no. 178-0328, pp. 26‒29. Suzuki seems to have interpreted the decay of Yōchite’s grave as reflecting a lack of proper respect for his elders on Setokurero’s part, but in fact, it was probably a reflection of the wide difference between Japanese and Ainu funerary customs. Japanese tradition requires regular visits to care for the graves of the dead, whereas in Ainu culture, the spirits of the dead should be left to rest undisturbed.

See Hori and Muragaki, ‘Hori Toshitada Muragaki Norimasa Karafuto-tō Keibi Mikomisho’; Hiwa, Jinsei Ideorogī, pp. 40‒41.

See the collection of documents from Setokurero’s family held in the Library of Hokkaido University (accessed 10 October 2020). The relevant documents in this collection (nos. 10‒13) are simply labelled ‘Year of the Boar’, using the twelve-year cycle. This could be either 1851 or 1863, or even a date earlier than 1851. Nishizuru Sadayoshi, in his 1941 Karafuto no Rekishi, interpreted this as a reference to 1851, but Setokurero clearly still held the position of elder in 1853 and 1854, so the succession documents must refer to 1863. See Nishizuru Sadayoshi, Karafuto no Rekishi, Tokyo, Kokusho Kankōkai, 1977 (original published in 1941), pp. 161‒162.

Rudanovskii’s journals indicate, that, like a number of well-to-do Ainu of that era, Setokurero probably had more than one wife; on polygyny, see Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, Illness and Healing among the Sakhalin Ainu: A Symbolic Interpretation, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, p. 25.

In 1787, Ainu villagers from Tomarioro, a little to the south of Nayoro, drew a map of the west coast of Sakhalin for La Pérouse, and informed him that Sakhalin was an island with a navigable passage between it and the mainland, but a misunderstanding of later information provided by Oroch villagers from the Lower Amur region led La Pérouse to report incorrectly that the Tartar Straits were not navigable by ocean-going vessels. See Tessa Morris-Suzuki, On the Frontiers of History: Rethinking East Asian Border, Canberra, ANU Press, 2019, chapter 5.

Leopold von Schrenck, Reisen und Vorschungen, St. Petersburg, Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vol. 3, part 2, p. 622.

Dobrotvorskii, Ainsko-Russkii Slovar’, p. 46; this passage has been translated into Japanese as meaning that the Manchus taught Yōchite to read and write their language, but this seems to be a mistranslation of the Russian word ‘gramota’, as ‘literacy’, whereas in this context it means an official document or diploma; see Nakamura Kazuyuki, ‘Chūgoku Shiryō kara Mita Ainu no Hoppō Kōeki’, lecture presented to the Ainu Minzoku Bunka Zaidan, 20‒21 August, 2005, p. 148.

Bronislaw Piłsudski, ‘Selected Information on the Ainu Settlements of Sakhalin’, in Bronislaw Piłsudski, ed. Alfred F. Majewicz, The Collected Works of Bronislaw Piłsudski, vol. 1, Berlin and New York, De Gruyter Mouton, 1998, pp. 311‒330, citation from p. 330.

For example, Nishizuru, Karafuto no Rekishi, pp. 161‒162; Hora, Karafuto Shi Kenkyū, pp. 146‒148; Nakamura ‘Chūgoku Shiryō’ The best account of the story is still the information given in Akizuki Toshiyuki’s Nichiro Kankei to Saharintō, particularly pp. 50, 112‒113, and 129‒130, on which I have drawn with gratitude. Akizuki is always conscious of the Ainu role in Japan-Russia relations; but his book is an overview of the two countries’ negotiations, so the role of Setokurero and his family occupies only a few sentences, with some of the most interesting information appearing in the footnotes.

Author unknown, trans. Bronislaw Piłsudski, ed. Alfred F. Majewicz, ‘Prayer to Guardian Deities upon a Journey on Foot in the Forest (from the Bay of Patience to the Valley of the River Tym)’, in Bronislaw Piłsudski, ed. Alfred F. Majewicz, The Collected Works of Bronislaw Piłsudski, vol. 2, Berlin and New York, De Gryuter Mouton, 1998, pp. 353-356. (I have made minor punctuation and grammatical adjustments for the sake of clarity).