Abstract: Indigenous people are often depicted as helpless victims of the forces of eighteenth and nineteenth century colonial empire building: forces that were beyond their understanding or control. Focusing on the story of a mid-nineteenth century diplomatic mission by Sakhalin Ainu (Enchiw), this essay (the first of a two-part series), challenges that view, suggesting instead that, despite the enormous power imbalances that they faced, indigenous groups sometimes intervened energetically and strategically in the historical process going on around them, had some impact on the outcome of these processes. In Part 1, we look at the story of one Sakhalin Ainu family over multiple generations in order to highlight the strategic place of the Sakhalin Ainu in cross-border relationships – particularly in the relationship between China and Japan – from the early eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century.

Keywords: Sakhalin; Sea of Okhotsk; Ainu; China; Qing Empire; Japan; Matsumae Domain; Santan trade; indigenous people.

Part 2 – Voices and Silencers appeared in the December 1 issue.

The Mission

In late December 1853, about six months after US Commodore Matthew Perry arrived in Uraga Bay on his mission to ‘open’ Japan to the world, a Sakhalin Ainu (Enchiw) elder named Setokurero set out from the village of Nayoro on the west coast of Sakhalin island on his own crucial diplomatic mission.1 He travelled in a convoy of fifteen dog sleighs through the winter blizzards, accompanied by a retinue of some twenty Ainu elders from surrounding villages and one Nivkh man from the Amur region of mainland Asia.2 They were heading for Kushunkotan on the southern shores of Sakhalin, where the Japanese had established a fortified trading post in the early nineteenth century, and where the Russians had also recently landed to stake their rival claim to the island. The aim of the Ainu elders’ mission was to learn more about Russo-Japanese competition for control of Sakhalin, to express their own views on the matter, and to seek Russian help in resisting Japanese exploitation of the Ainu.

Sakhalin Ainu Dog-Sleigh

(From Kita Ezo Zusetsu, vol. 2 early 19th Century,

National Archives of Japan, Edited to remove page breaks from image.)

The Ainu of Sakhalin, Hokkaido and the Kurile Islands, like the Nivkh and Uilta indigenous peoples who also inhabited Sakhalin, lived in small self-governing villages and did not have any single dominant chief, but Setokurero was a particularly well known and influential elder. He was respected for his oratorical skills3, and his village and family had a special place in Sakhalin history (which we will explore further). His coastal community of Nayoro was – in terms of the modern concept of towns or even villages – tiny. In 1853, it consisted of six houses on either bank of a small marshy river, containing a population of around fifty people.4 But it was a crossroads and emporium on a far-reaching trade route whose tentacles stretched, at one end, deep into the heartland of the Chinese Empire, and at the other end to the Shogunal capital of Edo (soon to become Tokyo) and beyond.5 From the Chinese side, items like silk brocade, cotton cloth, metalware, decorative blue beads, tobacco and smoking pipes flowed into Nayoro and other points on the Sakhalin trade route, and some of these goods (particularly Chinese brocades) travelled on to the luxury goods markets of Japan. From the Japanese side came items such as rice, saké, miso paste, and pots and pans. The medium of exchange was ‘soft gold’ (as the Russians called it): fur, in the form of the pelts of sable, fox, sea otters and other animals hunted by the indigenous people of the region.

Manchu Robes in Southern Sakhalin, early 19th century

(Source: Karafuto Fūzokuzū, Tokyo National Museum)

This, then, was one of just four narrow gateways through which Japan maintained contact with the outside world throughout its so-called ‘closed country’ era from the early seventeenth to mid-nineteenth centuries (the others being Nagasaki, the Ryūkyū Kingdom and the island of Tsushima).

Ever since the end of the eighteenth century, Japanese officials and merchants had been encroaching on Sakhalin from the south, attempting to take over direct control of this trade. Edicts had been issued to cut the Ainu out of the commercial network, forcing them instead to sell furs to Japanese officials, who would then trade directly with merchants from Manchuria. These merchants were commonly known collectively as ‘Santan’: most came from the indigenous Ulchi, Nanai and Oroch communities living in the region around the mouth of the Amur River, though some were members of the Nivkh community, who lived both on Sakhalin Island and on the adjacent mainland. As we shall see later, in 1853 the Japanese had not yet succeeded in establishing a monopoly over the Santan trade, and commercial exchanges between Santan, Ainu and other Sakhalin people continued to thrive in Nayoro. Setokurero had long witnessed the growing presence of the Japanese in Sakhalin – he was probably over sixty years old when he set out on his mission to Kushunkotan6. But in the past few months, the people of the Nayoro region had received reports of unsettling new developments. The world around them, it seemed, was in the midst of unimagined transformations.

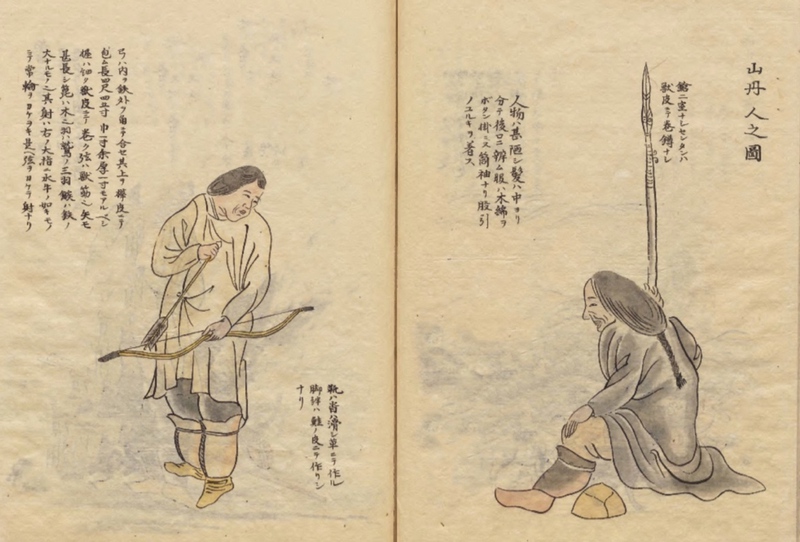

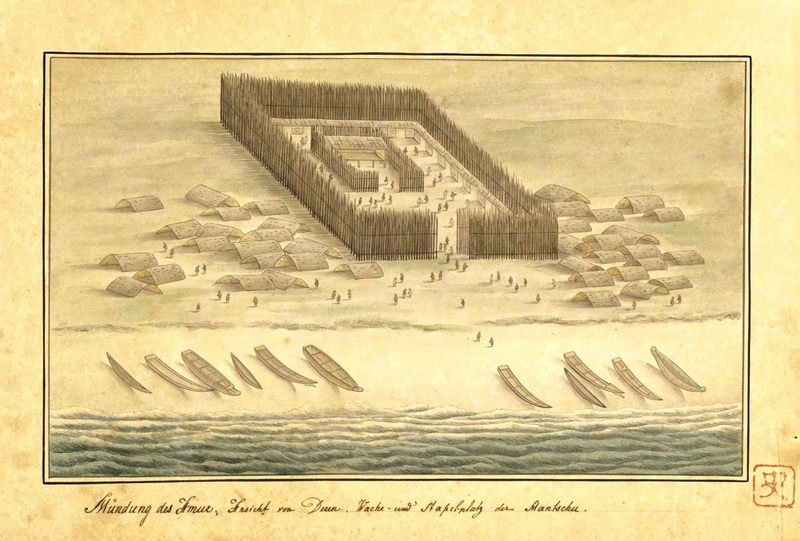

A Japanese Image of Santan Traders in Sakhalin

(Source: Kondō Morishige, Henyō Bunkai Zukō, vol 3, Japanese National Archives).

News of the arrival of Americans in Japan had quickly reached Sakhalin Ainu communities.7 Then in the autumn of 1853, a Russian military contingent landed on Sakhalin and set up camp next door to the Japanese settlement at Kushunkotan. At about the same time, a small party of Russians arrived in Nayoro by boat from the Asian continent, and it became clear to the Ainu of the Nayoro region that the Russians and the Japanese were engaged in a struggle for control over their land. On reaching Kushunkotan, Setokurero’s plan was to meet the head of the Russian force there – Nikolai Vassilievich Busse – and present to him the Ainu perspective on the past and future of the island. After meeting Busse, he and other members of his mission would then visit Japanese officials in Kushunkotan to negotiate with them. In Ainu society, the key forum for resolving important disputes is the caranke – a prolonged debate in which various sides set out their views on an issue, and their opinions are discussed until a solution is reached. Setokurero probably envisaged the meetings with Busse and the Japanese officials as a form of caranke, where the Ainu representatives would explain their ancient connection to the land of Sakhalin, learn more about the intentions of the Russians and the Japanese, and reach an agreement.

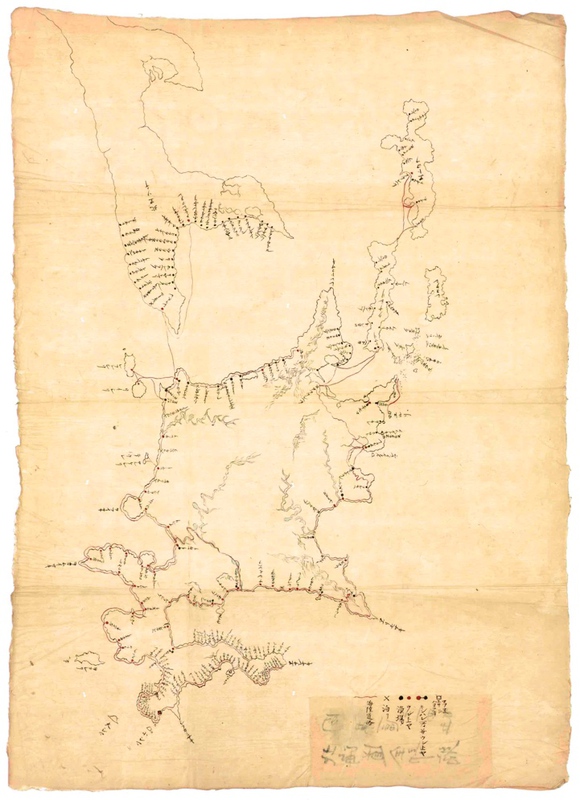

Map of Sakhalin and Surrounding Region.

(Modern place names and borders in black, historical place names in red)

Setokurero’s mission was to have an ironic ending which vividly illustrates the misunderstandings, wilful ignorance and violence that characterised 19th century imperial incursions into Sakhalin, as into many other parts of the world. But the Nayoro elder’s journey to Kushunkotan, and the historical context in which it occurred, also sheds fresh light on the indigenous history of Northeast Asia, and on the processes of imperial expansion in the region. Above all, the historical role of Setokuro and his family challenges the widespread image of the indigenous people as passive victims of imperial forces that were beyond their understanding or control. In order to make sense of that role, though we need first to look at the wider context in which it unfolded.

Victims of History, Makers of History: Sakhalin Islanders and the Santan Trade

The history of the Santan trade has fascinated scholars for decades. From the point of view of historians of China, it is deeply connected to the story of the Qing Dynasty’s relationship with the peoples on the periphery of the Chinese empire;8 for historians of Japan, it is central to understanding Japan’s northward expansion and its encroachment into Ainu lands.9 Other researchers again have approached the subject from the perspective of Russian expansion into Northeast Asia.10 In the 1950s, historian Hora Tomio brought a variety of sources together in a pioneering study of the Santan trade11, and since then, scholars including Akizuki Toshiyuki, Sasaki Shirō, Brett Walker, Takakura Hiroki and Deriha Kōji12 have helped to give us an increasingly comprehensive image of the networks of trade, travel and cultural exchange which spanned the region from Hokkaido through Sakhalin to the Amur and Maritime regions of Manchuria and beyond.

The sources on which these scholars draw all have their own particular biases. Qing official documents emphasise the subordination of the peoples of the periphery to Chinese rule. Japanese documents highlight the exploitative aspects of the Santan trade, since this enabled the Japanese Shogunate and Matsumae Domain (which acted as the intermediary in relations with Ainu for much of the seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries) to present themselves as ‘saviours’ of the Sakhalin Ainu, thus justifying Japanese expansion in the region. As the frontier of Japanese power moved north, these documents also increasingly proclaimed the dominance of the Japanese over the Ainu. The writings of Russian travellers and officials, meanwhile, tend to stress the independence of the Ainu both from Chinese and from Japanese rule, because this (in the imperial logic of the day) meant that they were ‘available’ to be placed under Russian control and turned into subjects of the Tsar. Triangulating these three sources of knowledge, though, can help to present a fuller picture of this history; and, as Brett Walker and others have shown, Ainu oral traditions shed important light on indigenous perceptions of relations with surrounding peoples.13

Earlier works often depicted Sakhalin islanders as hapless victims of the forces that surrounded them, but some recent writings take a different view of the past. For example, discussing the trans-border activities of indigenous people on the fringes of the Chinese and Russian empires in the mid-19th century, historian Sasaki Shirō writes: ‘it would seem that the borders in Northeast Asia were determined without any involvement by the local people. However, a detailed examination of the documents and people’s memories reveal some common phenomena. The people did not tolerate the changing conditions passively. Instead, they did their best to maintain a political-economic system that had greatly benefitted them, and, when they understood that it would be impossible to retain it, they tried to adapt to the new system.’14 Questions of violence and exploitation versus autonomy and agency are always delicate ones, and in this history, all were clearly present throughout. But the story of Setokurero’s mission to Kushunkotan reinforces the impression that the indigenous people of the region did indeed ‘not tolerate the changing conditions passively’, but energetically and strategically intervened in the historical process going on around them, and, despite the huge power imbalances involved, achieved some successes.

The impact of modern borderlines on geography and intellectual life also obscures another crucial feature of Sakhalin history. Because many recent studies of the region are written from the perspective of a particular national history, and because modern ethnographic knowledge draws firm dividing lines between distinct ethnic groups, the depth and intensity of the interaction between the various indigenous groups of the region often disappears from view. Anthropological works tend to focus on one particular group: either the Sakhalin Ainu or the Nivkh or the Uilta. Histories written from the standpoint of Japanese northward expansion concentrate on the relationship with the Ainu, while those that deal with the eastward expansion of Russian power are more often concerned with relations between the Russians and the Nivkh.

But indigenous oral histories, as well as eighteenth and nineteenth century written records, make it clear that the lives of the three main indigenous groups on Sakhalin formed an integrated whole. Each group had its own identity and its own language: indeed, Ainu, Nivkh and Uilta are linguistically unrelated to one another. The three groups were also distinguished by differing styles of dress and had their own patterns of family relationships. The Nivkh, who had lived in Sakhalin and in the area of the Asian mainland around the mouth of the Amur River at least since the 2nd-1st millennium BCE, subsisted mainly through fishing, hunting and the raising of domestic dogs, as did the Sakhalin Ainu, whose ancestral origins on Sakhalin have been traced back at least to the late Jōmon Era (roughly 1500 to 300 BCE). The Uilta, who are believed to be more recent migrants from the mainland to Sakhalin, were primarily fishers, hunters and reindeer herders, and only rarely kept dogs.15

But there were also many fishing and hunting techniques that all groups shared, and cultural practices such as the bear ceremony were (with minor variations) common to all. The houses in which Ainu and Nivkh lived during the summer months were readily distinguishable from one another – Nivkh people lived in wooden chalets on raised platforms, while Ainu lived in cottages whose walls and roofs were covered with tree bark – but in winter both groups moved back from the coast into virtually identical semi-underground houses built to provide protection from the bitter cold. Many indigenous people (particularly Uilta) were bi- or tri-lingual, speaking the languages of their neighbours as well as their own. In the central areas of Sakhalin, Ainu, Uilta and Nivkh villages sometimes stood side-by-side, everyday contact between the groups was taken for granted, and intermarriage was quite common. Until the mid-19th century, for example, the important settlement called Big Village (Porokotan in Ainu, Plyvo in Nivkh), a little over half way up the west coast of the island, was inhabited by more or less equal numbers of Ainu and Nivkh, and some Ainu families also lived alongside Nivkh families further north. On the east coast, Lake Taraika was surrounded by settlements of Ainu, Nivkh and Uilta living side by side, and Uilta and Nivkh villages stood next to one another in a number of regions throughout northern Sakhalin.16 It was the arrival of foreign colonizers that was to carve harder geographical and conceptual boundaries between these groups.

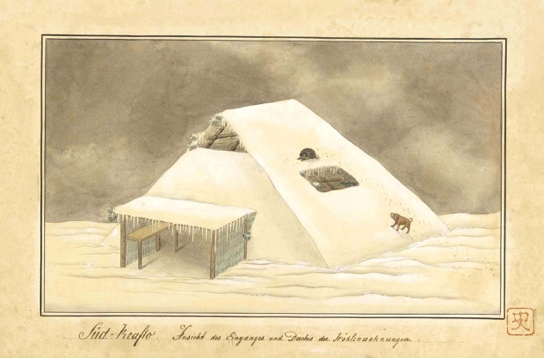

A Winter Semi-Underground House on Sakhalin

(Source: Karafuto Fūzokuzū, Tokyo National Museum)

The Emergence of the Santan Trade

The Santan trade had multiple layers. Its substratum was a web of voyages by the region’s indigenous people, criss-crossing the narrow Tartar Straits in small boats to trade or sometimes to seek marriage partners. These voyages, mentioned casually in early European accounts of Sakhalin,17 had been going on since time immemorial. Superimposed on this local commerce was the waxing and waning influence of the Chinese empire, which both stimulated and reshaped trade between the Asian mainland and Sakhalin. As the Chinese empire expanded, indigenous communities living further inland, on the upper reaches of the Amur River and its tributaries, obtained increasing access to Chinese goods, and these were then traded down the river to become crucial elements in commerce across the Tartar Straits.

Contacts between the Chinese empire and the people of Sakhalin go back at least to the era of Mongol dominance and the establishment of the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368). The official history of the era, compiled soon after the end of the dynasty, records several military clashes between the Mongols and ancestors of the Sakhalin Ainu (who were referred to in Chinese documents as the as ‘Ku-wu’).18 During the Ming Dynasty (1368‒1644) some efforts were made to impose the collection of tribute on the indigenous people of the Amur region and Sakhalin – Wada Sei even cites a late Ming Dynasty record which appears to refer to marriages between Chinese officials who travelled to Sakhalin and local Nivkh women19 – but these tributary relationships atrophied as Ming power declined. By the time Manchu leaders established China’s Qing Dynasty in 1644, though, the Manchus had already begun to create their own powerful networks of influence over the peoples on the eastern fringes of Manchuria, and they would continue to expand those networks throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.20

In the 1640s, the Russians made their first appearance in the Lower Amur region. Spearheaded by miscellaneous bands of officials, Cossacks and private profiteers, Russian expeditions reached the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk by 1643 and the mouth of the Amur River by 1644, forcing local people to pay yasak (fur tax) as they went.21 These incursions led to armed clashes between the Chinese and Russian empires in the 1680s, and in 1689 the Treaty of Nerchinsk was signed, confining Russian activity to an area to the north of the mouth of the Amur. From then until the mid-19th century, the Russians retreated from this area, and their expansion focused instead on the far northern areas of Chukotka and the Kamchatka Peninsula. But the conflict with Russia had encouraged the Qing Dynasty to intensify its efforts to collect information on and exert power over the people of the borderlands, and the year after the signing of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, Manchu officials were sent to the Lower Amur and Sakhalin to investigate the geography and society of the area, and to extract fur tax from local villagers. This was followed by several other visits to the island, conducted as part of efforts by the Qing court to map the area.22

By the 1730s, these preliminary forays had turned into more concerted efforts to exert Qing authority over some at least of the Sakhalin islanders. Control was imposed indirectly, by appointing senior figures within indigenous communities to the status of ‘clan chief’ (hala-i-da) or ‘village chief’ (gasan-da or mokun-da).23These titles, which were identical to the ones used to organize Manchu society itself, made the bearer responsible for the collection and delivery of tribute, to be paid to Manchu officials in the form of furs at tribute posts set up in the Lower Amur region. Though demands for tribute placed pressure on the region’s indigenous society, they also created new opportunities for trade and cultural exchanges. Manchu officials gave tribute-givers allowances of rice, salt and other necessities during the period of their mission, and rewarded them with valuable gifts. Tribute missions took place in the summer months, and generated lively events that resembled trade fairs, where many cultural and language groups from around the region exchanged goods and information on the fringes of the more formal tribute ceremonies. The Qing Dynasty also encouraged marriages between selected Manchu officials and the daughters of the officially designated indigenous clan chiefs.24

In 1732, a group of Manchu officials travelled to Sakhalin to impose this tribute system on communities in the north and west of the island. Their arrival seems to have caused considerable consternation amongst local villagers. Over eighty years later, when the Japanese traveller Mamiya Rinzō reached Sakhalin, he met Nivkh villagers who recounted their communal memories of people fleeing into the mountains to escape from the intruders.25 Gradually, though, many re-emerged from hiding. People from eighteen villages, with a population of 146 households, were organized into six clans (four from Ainu communities and two from Nivkh communities), and hala-i-da were appointed for each clan. One of these clans covered the Nayoro area (referred to in the Manchu documents of the time as ‘Yadan’). The man appointed as hala-i-da of this clan was Setokurero’s great-grandfather Yaepikarainu.26 This marked the start of a family dynasty of Nayoro hala-i-da which continued until the time of Setokurero’s son in the second half of the nineteenth century.

While trade links across the narrow Tartar Straits between Sakhalin and the Lower Amur were growing, Sakhalin Ainu were also trading with their southern Ainu neighbours across the wider and stormier straits which separate their island from Hokkaido (then known to the Japanese as Ezo). The focus of trade here was the outpost of Sōya, in the extreme north of Hokkaido. With the establishment of Japan’s Tokugawa Shogunate in the early seventeenth century, the domain of Matsumae (based in the southern tip of Hokkaido) became – from the Japanese perspective – the sole guardian of relations between Japan and the Ainu. In the 1630s, the lords of Matsumae sent expeditions northwards to investigate the still largely unknown realms inhabited by the Ainu, and three of these expeditions even travelled as far as Sakhalin, but this search for knowledge was not followed up for almost a century.27 Meanwhile, in the 1680s Matsumae established a trading post at Sōya, where their officials collected tribute from the local Hokkaido Ainu. Chinese products such as brocades, bought by Hokkaido Ainu from Sakhalin Ainu, became the most important of these tribute goods.28 So, by the late seventeenth century, there was a regular channel which promoted the flow of trade from China via the Amur, Sakhalin and Sōya to Japan, in the process also transforming the lives of Sakhalin islanders, as foreign items like silk, cotton and rice were incorporated into their everyday lives.

The social and political dimensions of indigenous life, though, remained largely untouched. Villages continued to be self-governing, and social order was still maintained according to indigenous law. This is interestingly illustrated by a case discussed by Sasaki Shirō. In 1742, a Manchu official who had married an indigenous Sakhalin woman became involved in a quarrel with some visiting Ainu tribute givers at a tribute post on Lake Kizi in the Lower Amur region, and killed a number of the Ainu. Local Manchu officials arrested the chief assailant, and then travelled to Sakhalin, where they presented the relatives of the victims with gifts as compensation and invited them to Kizi to testify at the trial of the perpetrator. But the Ainu refused to attend the trial. They had their own notions of justice and retribution, which were different from those of the Manchus and Chinese, and they rejected the invitation to take part in an alien system of trial and punishment.29 Chinese and Manchu officials had neither the intention nor the capacity to radically alter the social and cultural basis of Sakhalin’s indigenous societies; but they did have the power to enforce their demands for tribute.

Yaepikarainu’s and Yōchite’s Generation: Nayoro, Manchuria and the Growth of the Santan Trade

Setokurero’s great-grandfather, the Nayoro elder Yaepikarainu, was by all accounts a formidable and ruthless man. The Japanese official Mamiya Rinzō, who visited Nayoro in 1809, met three Ainu men who were then in their seventies and could remember stories from the first half of the eighteenth century. According to them, on one occasion when Nivkh and other indigenous traders from the Lower Amur region came to Nayoro to trade, Yaepirakainu killed more than ten of them and stole their goods. Some of the traders escaped the slaughter and complained to Manchu officials, who arrived in Nayoro on three ships to bring the renegade elder to heel. A number of those complicit in the murders were made to hand over their most valued treasures as compensation, and Yaepirakainu, as the ringleader, was forced to surrender his two sons, Kanntetsuroshike and Yōchite30(Setokurero’s grandfather) to be taken to Manchuria as hostages.31

Hostage taking was a common means by which the more powerful partners in the economic and political relations of the region (usually mainlanders) imposed their will on the less powerful (usually Sakhalin islanders). It was used both by Manchus and Santan, not just to punish serious crimes like Yaepirakainu’s, but also to discipline those who fell into debt. Debtors or their children would be taken away to the Lower Amur region as hostages, and this practice became increasingly common as over-hunting placed growing pressure on Sakhalin’s resources. Santan traders also sometimes took island women as wives, with or without the consent of their families (and most likely without the consent of the women themselves). Mamiya Rinzō reported that Ainu from the small island of Rishiri off Hokkaido often came to Sakhalin, and that women (particularly widows) from Rishiri were sometimes kidnapped by Santan or sold by their own families. As a result, it was common to see ‘women with tattooed mouths’, emblematic of Ainu culture, in Santan villages on the Asian mainland.32

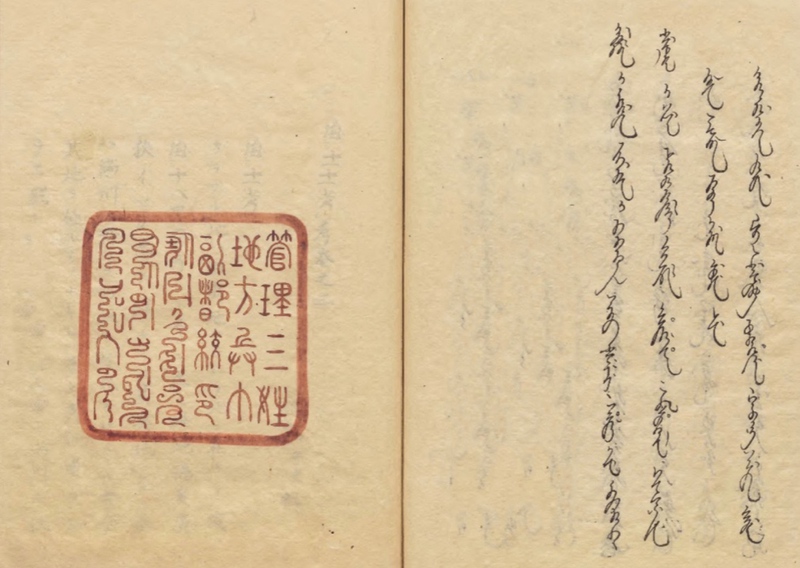

From a Japanese Copy of the Manchu Document appointing Yōchite as hala-i-da,with its Chinese seal

(Source: Kondō Morishige, Henyō Bunkai Zukō, vol 3, Japanese National Archives).

The practice of hostage taking involved considerable violence on the one side and fear on the other, and the prevalence of this practice by the early nineteenth century was emphasised by the Japanese Shogunate and Matsumae Domain as a reason for Japan to take over control of the Santan trade in order to protect the Ainu. But it was not a system of permanent slavery. Hostages were often allowed to go back to Sakhalin once they had worked off their debts, and those who did return sometimes came home with enhanced trading networks and increased authority because of their experiences of life in Manchuria.33 Interestingly, despite his crime, Yaepirakainu evidently remained hala-i-da of the Nayoro area. He appears in Manchu documents listing Sakhalin clan leaders in 1743, 1754 and 1760; and after several years in Manchuria, his son Yōchite returned to his home village and took over the position from his father.34

Unlike his father – a man remembered (according to the information given by elderly Ainu to Mamiya Rinzō) as having been ‘crafty and brutal’36 ‒ Yōchite seems to have commanded considerable respect. As a hala-i-da, his main task was to collect sea otter and sable furs from the Ainu of his region and organize the missions to the Manchu tribute post on the Amur: a substantial task, since these expeditions might last for as long as four months.36 His status, though, also gave him a degree of authority over the Santan traders who came to the Nayoro region, enabling him and other hala-i-da to provide local people with some protection from exploitation by the mainlanders.37

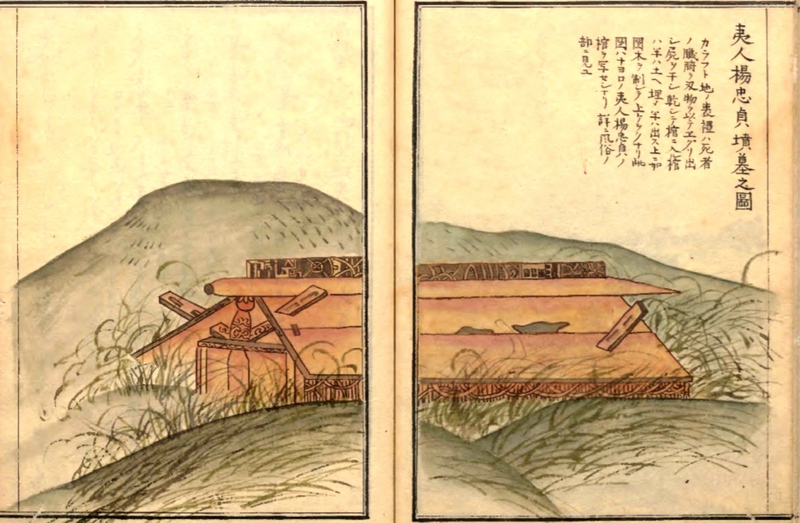

Illustration of the Tomb of Yōchite, near Nayoro

(Source: Kondō Morishige, Henyō Bunkai Zukō, vol 3, Japanese National Archives).

As well as making frequent visits to Manchuria, in the 1770s Yōchite (who had by then recently succeeded to the position of Nayoro hala-i-da) also travelled as far as the Japanese trading post at Sōya where, magnificently arrayed in a Manchurian silk brocade robe decorated with a three-clawed dragon, he met officials from Matsumae Domain, to whom he presented a map he had drawn, depicting areas of Manchuria as yet unknown in Japan. The Matsumae officials read the map as showing a sea with six islands to the northeast of Santan territory, but this must have been a misinterpretation of Yōchite’s cartography, because the first ‘two islands’ were labelled ‘Icha’ and ‘Botton’, clearly a reference to the city of Ice Hoton (Ichahoton) or Sanxing (present day Yilan, near Harbin in Northeastern China)38, one of the two administrative centres from which the Qing Dynasty exerted control over the Amur region and Sakhalin (the second being Ninguta – present day Ning’an). Another name from Yōchite’s map was ‘Makuta’, which may be indicate the town of Mukden (Shenyang).39 Yōchite’s historical role and influence were reflected in the large and beautifully carved wooden tomb near Nayoro in which he was buried following his death, which probably occurred in the 1790s.40

Yayenkurainu’s and Shirotoma’s Generation: Nayoro as Crossroads

On Yōchite’s death, the position of Nayoro hala-i-da was inherited by his son (Setokurero’s father41) Yayenkurainu, who appears to have begun making visits to Manchuria in his father’s lifetime, and continued the practice of leading regular tribute missions to the Amur every one or two years.42 The presentation of tribute took place in a temporary summer fort established by the Manchu officials at Deren on the shores of Lake Kizi, a broad section of the Amur River some way inland from the river mouth. Yayenkurainu, accompanied by perhaps a dozen or so other Ainu, would travel by boat up the west coast of Sakhalin, stopping overnight at the Ainu, Uilta and Nivkh villages along the route until they reached a point near Cape Nakko, the headland closest to the Asian continent. From there they made the relatively short crossing to one of the small indigenous villages on the mainland, some way south of mouth of the Amur River, and usually dragged their boats overland across a pass through the hills which offered a short-cut to Lake Kizi.

Meanwhile, Manchu officials had travelled down the river from Ice Hoton to open up the Deren tribute post, and Nivkh, Ulcha, Nanai and other hala-i-da with hundreds of their companions had gathered from all over the north-eastern Manchurian region.43 On their arrival, Yayenkurainu and a couple of other prominent Ainu would immediately go to one of the large boats where the Manchu officials stayed during the tribute season to pay their respects and receive an allowance of millet or other foodstuffs. The Ainu then built temporary camps outside the wooden palisade which surrounded the tribute post, waiting until it was their turn to take part in the formal tribute ceremony. This involved paying obeisance to three Manchu officials who were seated on a dais in the central compound of the tribute post, and presenting the most valuable of the furs that they had brought with them. In return, Yayenkurainu, as hala-i-da, received a roll of silk brocade, the gasan-da in the party were given rolls of damask, and untitled commoners received one roll of plain cotton each.

With the formal part of the proceedings out of the way, the participants were then free to move on to the equally important and doubtless more pleasurable task of private trading. While senior officials remained aloof from the tribute givers, the lower-ranked Manchus mingled easily with the indigenous visitors, reclining on the grass around the palisade to chat, smoke pipes, and exchange goods and gossip. Indigenous people from many parts of the region, as well as the junior officials themselves, visited each other’s temporary camps for meals and drinks, and traded items like tobacco, alcohol, ironware and fabrics.44 After returning home from these tribute missions, Yayenkurainu, like his father, was then able to travel south to the Japanese trading post at Sōya, where in 1785 (for example) he exchanged a length of crimson Chinese silk for several bales of rice, yeast, barrels of saké and items of clothing.45

The Scene at Deren During the Tribute Mission, early 19th century

(Source: Karafuto Fūzokuzū, Tokyo National Museum)

By offering people like Yayenkurainu privileged access to valuable goods, this system of tribute and trade clearly increased inequalities in Ainu society. But the friendships and commercial relationships forged during these visits to Deren and Sōya also gave many Sakhalin islander communities a network of connections that spanned a region from the borders of Korea to the fringes of the Russian empire in one direction and to Japan in the other. This was an important source of news about events in the world around them, and the networks were reinforced by the frequent arrival in Nayoro of Santan merchants, who often passed through the village on their trading journeys around Sakhalin.

By the early nineteenth century, though, the frequency of Yayenkurainu’s visits to Deren was declining. This was partly for personal reasons: Yayenkurainu suffered from an eye disease which meant that his sight was fading, and travel was becoming increasingly difficult.46 But there were also larger forces at work. By now, the power of the Qing state over the Lower Amur region and Sakhalin was gradually waning, and Manchu officials were having increasing difficulty in enforcing their demands for tribute. Meanwhile, Matsumae Domain and the Japanese Shogunate were developing a new interest in the lands to their north, and Japanese officials were starting to make an appearance even in Nayoro itself.

Japanese economic influence had gradually extended northward up the coasts of Hokkaido towards Sakhalin throughout the eighteenth century. Matsumae Domain’s trading posts in Hokkaido Ainu territory were initially under the firm control of domain officials, but during the eighteenth century they were entrusted to licenced merchants, who often made substantial fortunes not just from trade but also from fishing operations in which they employed Ainu as forced labour. In 1771, merchant Murayama Denbei was dispatched by Matsumae to investigate the possibility of establishing trading and fishing bases on the southern shores of Sakhalin, and in 1790 the first Japanese trade post was set up at Shiranushi, on the very southernmost tip of the island. Two Japanese guard posts were also built on the island at this time: one at Kushunkotan (present day Korsakov) on Aniwa Bay, the large gulf to the east of Shiranushi, and one at Tonnai (present day Kholmsk) on the west coast.47 The motives behind this renewed interest in Sakhalin were strategic as well as economic. A 1789 uprising by Ainu labourers in the fisheries in north-eastern Hokkaido and on Kunashir in the Kurile Islands had severely rattled the Japanese authorities, and growing signs of a renewed Russian presence in the region were also arousing anxiety, particularly following an armed raid on the Japanese guard post at Kushunkotan by a group of Russian soldiers in 1806.48 In response, a series of official Japanese expeditions were dispatched north to investigate Sakhalin, and in 1807 the Shogunate took over direct control of Japan’s interests in Sakhalin from Matsumae Domain.49

By the 1790s, a few intrepid Japanese officials were making the journey as far as Nayoro, where they visited Yayenkurainu and, with considerable fascination, inspected the Manchu investiture document which he had inherited from his father, as well as other messages sent by Manchu officials to the Nayoro hala-i-da. But by the time the two prominent Shogunal scholar-officials Mamiya Rinzō (1775‒1884) and Matsuda Denjūrō (1769‒1842) reached Nayoro in 1808, Yayenkurainu’s eyesight had degenerated to the point where he was no longer able to make the journey to Deren, forcing him to transfer this role to his younger brother, Shirotoma, who was invested as hala-i-da in his place.

Matsuda, who visited Nayoro briefly in the summer of that year, spent his one night in the village sleeping in an empty store hut, but was invited into Yayenkurainu’s house during the day, and recorded a fleeting glimpse of the women of the household, who so often remain invisible in this story. Women had a powerful and important role in Ainu society, but one that was largely separate from the role of men and seldom appears in the written record. In some parts of the region under their influence, Manchu officials appointed female as well as male gasan da, with specific authority over the women of the village50, but there is no direct evidence that this was done in Sakhalin. Women, though, clearly played an important part in the preparation and support for major journeys like the tribute missions to Deren. In Yayenkurainu’s household, Matsuda met three women whom he describes as being aged approximately in their forties, one of whom was probably Setokurero’s mother. The women served their Japanese visitor with wooden dishes containing a popular Sakhalin delicacy – ground herring roe moistened with fish oil.51

Matsuda’s main mission in Sakhalin was to investigate the Santan trade and the problem of Ainu indebtedness to Santan merchants: a problem which was increasing because of resource depletion and growing Ainu dependence on imported goods. In response to his reports, the Shogunate issued edicts forbidding Ainu from trading directly with Santan. Those who had fallen into debt were helped to repay their obligations, and sometimes forced to return goods for which they could not pay. Santan, as well as Nivkh and Uilta from northern Sakhalin, were now required to travel to Shiranushi, pay respects to the Japanese officials stationed there, and trade directly with them. Ainu, meanwhile, could no longer present tribute at the Japanese posts at Shiranushi and Sōya in the form of goods imported from Manchuria. Instead, they were required to bring furs which the Japanese would use to conduct their own trade with the Santan, thus reinforcing Shogunal control over contact with the outside world.52

These new regulations had important implications for the communities of the region, but Japanese officials had no means of enforcing the rules effectively, and their capacity to impose them diminished the further north they went. By the first decades of the 19th century (as we shall see), Japanese merchants were making growing inroads into the southern half of Sakhalin, setting up fisheries along the coast of Aniwa Bay and beyond. But the number of Japanese people actually living in Sakhalin, particularly in the winter months, was very small indeed, and Sakhalin islanders had both motive and opportunity to avoid their surveillance. The Russian geographer and ethnographer Leopold von Schrenck, who led a major scientific expedition to the Amur region and Sakhalin between 1854 and 1856, observed that Japanese officials tried as hard as possible to thwart the Santan trade ‘because they like to take possession of the fur they have seized from the Ainu. But they do this in a way that is severely damaging to the latter, by taking their goods in part under threat of punishment and through compulsory measures for very low prices, or sometimes for free, as a payment for alleged debts. So, the Ainu avoid trading with them wherever they can, and seek to sell their secretly retained fur goods to the Sakhalin Gilyak [Nivkh] or, even better, to the Amur Gilyak [Nivkh] and Olcha.’53

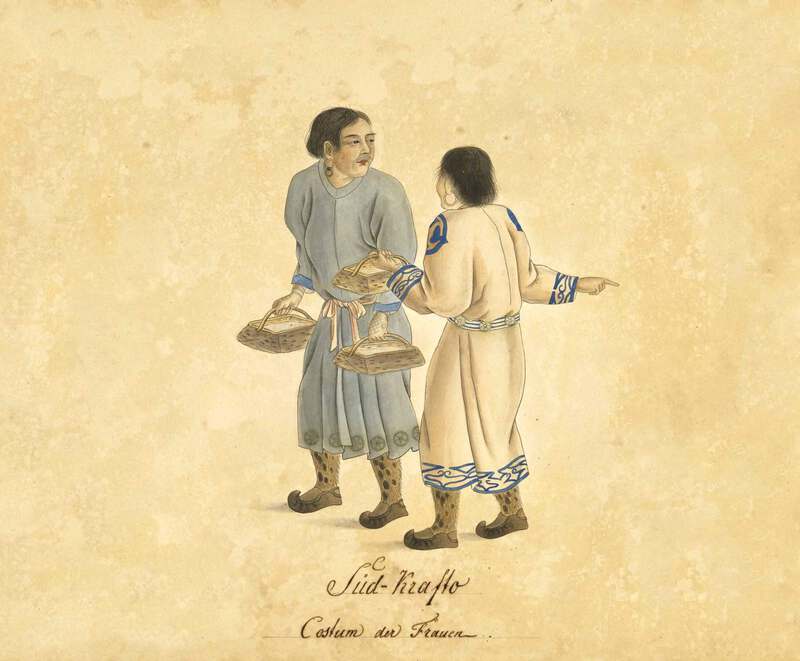

Sakhalin Ainu Women with Baskets of Food

(Source: Karafuto Fūzokuzū, Tokyo National Museum)

Setokurero’s Generation: The Santan Trade in a Changing Regional Order

Setokurero regarded himself as heir to his father’s and grandfather’s title of hala-i-da, and lovingly preserved the family’s Manchu documents, but by the time of his father’s death, the power of these documents had faded. During the first half of the 19th century, the Qing tribute system was crumbling from the fringes inwards, as Russian influence again began to spread into the Lower Amur region, and as private Chinese or Manchu traders found ways to circumvent state controls on trade with the region’s indigenous people.54 Manchu officials were no longer able to enforce the payment of tribute on Sakhalin islanders, and for the islanders themselves, there was less and less reason to travel to the Lower Amur. Setokurero himself never visited Manchuria, and, as he would later tell a Russian visitor, ‘he did not remember seeing the Manchus at his home village. It was always only Santan or Ssumeri [Nivkh] who came there for trade’.55

This shift in the regional order, though, made Nayoro more important than ever as a trade entrepot. Santan and Amur Nivkh stopped off at the village on their way to Shinanushi to trade with the Japanese. As Schrenck noted, the purpose of these trading expeditions was not just to visit Shiranushi, but also ‘to trade with the Ainu, and to obtain furs from them in return for cotton products, tobacco, pipes, glass beads and other Manchu-Chinese articles. This happens wherever they meet them, both on the east and the west coast of Sakhalin. A main point for this trade, however, is the village of Nayoro, not far from Kushunai, whither the Ainu go for this purpose even from a considerable distance, from the Bay of Aniwa etc.’56 Nayoro’s significance was partly an accident of geography. As well as being a stopping point for boats travelling down the west coast of Sakhalin to the Japanese trading posts in the south, the village was situated close to the narrowest part of the island, where a series of passes led across its mountainous spine to the rich fishing and hunting grounds around Lake Taraika on the east coast.

From there, Ainu, Nivkh and Uilta villagers and continental visitors also often travelled to the River Tym, which flows north-eastward through the centre of Sakhalin into the Sea of Okhotsk, to trade with the indigenous people who lived along its banks, far from the intrusive gaze of Japanese officialdom.57 The Nivkh who lived close to the Tym caught large amounts of fish and dried these on racks outside their houses, ‘not only for themselves and their dogs during the winter, but also as an object of trade with the Ainos, Oronchons [Uilta] and Gilyak [Nivkh] of the coast… and the Manguns [Ulchi] of the Amur. The Ainos bring to the Valley of the Tymy Japanese goods, the [Uilta] furs, the others copper, seals, Russian and Manchu merchandise’.58

But conditions for Sakhalin Ainu living further south, particularly around the Bay of Aniwa and on the southern reaches of the west coast, were very different from the situation around Nayoro, for, by the second decade of the 19th century, this part of the island had entered the period of history that Sakhalin Ainu would later remember as the ‘Date-Suhara Era’.59 In 1809, a business enterprise run jointly by the Japanese mercantile houses of Date and Suhara was given the right to establish fisheries in Sakhalin, and by the middle of the 19th century it had set up 32 fishing establishments, dotted along the shores the Bay of Aniwa, with another 16 extending along the west coast of the island to a point about fifty miles south of Nayoro.60 The Suharas had first come to prominence in the seventeenth century as the owners of a substantial fishing enterprise based in what is now Wakayama Prefecture in southern Honshū, and they went on to expand into lumber and charcoal trading, establishing a branch in Matsumae Domain in the late 18th century.61 There they joined forces with the Date family, a wealthy business clan from north-eastern Japan who had been running fisheries in Hokkaido for several decades.62 By the nineteenth century, they also had a finger in the pie of the Santan trade, and were shipping rice, sake and tobacco to Shiranushi to be exchanged for Chinese wares.63 In their fisheries, Suhara and Date worked on a grand scale, often using large dragnets, and by the middle of the 19th century they were employing thousands of Ainu workers in their fisheries in Hokkaido and Sakhalin.64

Map by Imai Hachikurō, Showing the Location of the Main Japanese Fishing and Trading Posts in Hokkaido and Sakhalin (mid-19th century, post 1838)

Sakhalin.64 (Source: Tokyo National Museum)

The Sakhalin fisheries operated only in the summer months – between about April and October. At the beginning of this period, a hundred or more Japanese overseers and others would arrive in Sakhalin from Hakodate in Hokkaido, where the enterprise was based, and collect Ainu workers – men, women and sometimes children – from the surrounding villages. Working conditions were, by all accounts, terrible. Japanese scholar Matsuura Takeshirō, who first visited Sakhalin in 1846, witnessed Ainu workers being forced to live in overcrowded temporary accommodation during the fishing season. Discipline was brutal, and the arriving Japanese fishing overseers not only regularly used their position to extort and cheat their workers, but also brought with them illnesses such as smallpox and venereal disease which spread among the local population.65 Ainu who became ill were shut up in a shed where they were forced to drink water mixed with fiery red pepper. If they refused or were unable to drink it, they were defined as ‘faking illness’ and sent out to work again.66

For the local Ainu, though, it was extremely difficult to escape labour in the fisheries, both because it was enforced through violence and because large-scale resource exploitation by the Suhara and Date enterprises destroyed the basis of the subsistence fishing on which their survival depended. Some, though, did flee north to areas beyond the reach of the Japanese overseers.67 In 1822, as the Russian threat to the north seemed for a while to be receding, the Shogunate handed control of the region back to Matsumae Domain, which did nothing to check the depredations of the fishery enterprises. Although Nayoro was far enough north to escape the direct impact of this exploitation in the first half of the 19th century, the Ainu of the Nayoro region were well aware of events further south. Protests about the Japanese fisheries were to become a central point of contention in Setokurero’s confrontation with the Japanese authorities in 1853.

Notes

Sakhalin Ainu also refer to themselves as ‘Enchiw’, the Sakhalin Ainu equivalent of the Hokkaido term ‘Ainu’, meaning ‘human being’. I have used the transliteration of Setokurero’s name given by Busse and by Mikhail Mikhailovich Dobrotvorskii. Dobrotvorskii was a linguist who wrote the first Ainu-Russian dictionary, and paid close attention to the transcription of Ainu names, and he also knew Setokurero personally (see Mikhail Mikhailovich Dobrotvorskii, Ainsko-Russkii Slovar’, Kazan, Universiteskaya Tipografiya, 1876, p. 46). Japanese official sources of the day generally transcribe his name as Shitokureran, with the final ‘-an’ clearly being a contraction of the honorific ‘-ainu’ added to the end of the names of senior Ainu men. Setokurero’s mission arrived at Busse’s headquarters near Kushunkotan on 7 January 1854, Julian calendar (25 December 1853, according to the Gregorian calendar); see Nikolai Vassilievich Busse, Ostrov Sakhalin i Ekspeditsiya 1853-1854 gg, St. Petersburg, F. S. Sushchinhskii, 1872, p. 85.

Busse, Ostrov Sakhalin, p. 85; Busse gives the number of sleighs as ten, but Rudanovskii, who probably had more opportunity to observe them, gives the figure as fifteen; see N. V. Rudanovskii (ed. I. A Samarin), ‘“Poezdki moi po Ostrovu Sakhalinu Ya Delal Osen’yu i Zimoyu”: Otchyoty Leitenata N. V. Rudanovskovo 1853‒1854 gg.’, reprinted in Vestnik Sakhalinskovo Muzeya, no. 10, 2002, pp. 137‒166, citation from p. 145. Rudanovskii transcribes the Ainu elder’s name as ‘Sitakurero’.

Busse, Ostrov Sakhalin, p. 72; Leopold von Schrenck, Reisen und Forschungen im Amur-Lände in den Jahren 1854-1856, Vol. 3, Part 2, St. Petersburg, Imperial Academy of Sciences, 1891, pp. 610-611.

Estimates of the Setokurero’s age vary quite widely. The Japanese official Muragaki Yosaburō, who met Setokurero on his visit to Sakhalin in 1854, described him as being over 60 at that time (cited in Akizuki Toshiyuki, Nichiro Kankei to Saharin-tō: Bakumatsu Meiji Shoki no Ryōdo Mondai, Tokyo, Chikuma Shobō, 1994, p. 129); Nikolai Vasilyevich Rudanovskii in 1857 estimated him to be in his seventies – see N. V. Rudanovskii, ‘Ekspeditsiya na Ov. Sakhalin v 1859 Godu s 1 Yulya po 1 Oktabrya’, reprinted in Vestnik Sakhalinskovo Muzeya, no. 21, 2014, pp. 75‒75, quotation from p. 58. On the other hand, Dobrotvorskii, who lived in Sakhalin between 1867 and 1872 and met Setokurero there, describes him as being a centenarian, which would have made him at least eighty at the time of his meeting with Busse; see Dobrotvorskii, Ainsko-Russkii Slovar’, p. 46.

It is likely that the Ainu of Nayoro knew about Perry’s arrival in Japan. Busse notes that when his Russian force landed at Kushunkotan, almost the first word that the local Ainu inhabitants said to them was ‘Americans’. The rather predictable response from the Russians was to explain that they were not American but that ‘the Americans want to come to Sakhalin and that therefore we want to settle with them [the Ainu] in order to protect them from the Americans’; Busse, Ostrov Sakhalin, p. 23.

See, for example, Sei Wada, ‘The Natives of the Lower reaches of the Amur as Represented in Chinese Records’, Memoirs of the Research Department of Toyo Bunko, no. 10, 1938, pp. 40‒102; Robert H. G. Lee, The Russian Frontier in Ch’ing History, Cambridge Mass., Harvard University Press, 1970; Sasaki Shirō, ‘Amūru Shimoryūiki no Shominzoku no Shakai, Bunka ni okeru Shinchō Shihai no Eikyō ni tsuite’, Kokuritsu Minzokugaku Hakubutsukan Kenkyū Hōkoku, vol. 14, pp. 661‒711; Matsuura Shigeru, Shinchō no Amūru Seisaku to Shōsū Minzoku, Kyoto, Kyōto Daigaku Gakujutsu Shuppankai, 2006.

For example, Hora Tomio, Karafuto Shi Kenkyū: Karafuto to Santan, Tokyo, Shinjusha, 1956; Kodama Kyōko, ‘18, 19 Seiki ni okeru Karafuto no Jūmin: “Santan” o Megutte’, in Hoppō Gengo Bunka Kenkyūkai ed., Minzoku Sesshoku: Kita no Shiten kara, Tokyo, Rokkō Shuppan, 1989, pp. 31-47; Akizuki, Nichiro Kankei to Saharintō; Hokkaidō Kaitaku Kinenkan ed. Santan Kōeki to Ezo Nishiki, Sapporo, Hokkaidō Kaitaku Kinenkan, 1996; Brett Walker, The Conquest of Ainu Lands: Ecology and Culture in Japanese Expansion, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2001, Chapter 5; Deriha Kōji, ‘Kinsei Makki ni okeru Ainu no Mōhi Jūshu Katsudō nit suite: Mōhi Kōeki no Shiten kara’, Kokuritsu Minzokugaku Hakubutsukan Kenkyū Hōkoku, vol. 34, pp. 97‒163.

For example, E. G. Ravenstein, The Russians on the Amur: Its Discovery, Conquest and Colonisation, London, Trübner and Co, 1861; F. A. Golder, Russian Expansion on the Pacific, 1641‒1850, Cleveland, Arthur H. Clark Company, 1914; A. I Alekseyev, Amursaya Ekspeditsiya 1849-1855, Moscow, Mysl, 1974; A. V. Smolyak, Etnicheskiye Prosessy Narodov niznego Amura i Sakhalin, Moscow, Nauka, 1975; Shiro Sasaki, ‘A History of the Far East Indigenous Peoples’ Transborder Activities Between the Russian and Chinese Empires’, Senri Ethnological Studies, vol. 92, 2016, pp. 161‒193.

Akizuki, Nichiro Kankei to Saharintō; Sasaki, ‘History of the Far East Indigenous Peoples’ Transborder Activities’; Walker, Conquest of Ainu Lands; Hiroki Takakura, ‘The Ainu and Indigenous Trading in Maritime Northeast Asia: A Comprehensive Review of the Histories of Hokkaido, Amur-Sakhalin and Chukotka’, Tōhoku Ajia Kenkyū, vol. 11, 2007, pp. 115‒136; Deriha, ‘Kinsei Makki’.

See, for example, Richard Zgusta, The Peoples of Northeast Asia Through Time: Precolonial Ethnic and Cultural Processes Along the Coast Between Hokkaido and the Bering Strait, Leiden and Boston, Brill, 2015

Leopold von Schrenck, Reisen und Vorschungen, St. Petersburg, Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vol. 3, Part 1, 1881, pp. 16-17.

For example, drawing on material collected by Jesuit missionaries Jean François Gerbillon and Thomas Pereira, who visited the Amur region in the 1680s while acting as interpreters between the Chinese and Russians during the Nerchinsk negotiations, French Jesuit historian Jean Baptiste du Halde (1674‒1743) wrote that the Chinese emperor had sent Manchus to Sakhalin in boats belonging to the ‘Ke Tschng Ta Tse’ or ‘Fiatta’ [Nivkh] who ‘live on the shores of the sea and trade with the inhabitants of the western part of the island [of Sakhalin]’; see J. B. du Halde, Description Géographique, Historique, Chronologique, Politique et Physique de l’Empire de Chine et de la Tartarie Chinoise, vol. 4, The Hague, Henri Scheurleer, 1736, p. 14.

Wada, ‘Natives of the Lower Reaches of the Amur River’, pp. 80-81; see also Walker, Conquest of Ainu Lands, p. 133.

Wada, ‘Natives of the Lower Reaches of the Amur River’, p. 82. The references in the documents are to a people called the ‘Chi-li-mi’ (the term generally used in early Chinese texts to refer to the Nivkh) living next to the Ku-wu (Ainu).

Basil Dymytryshyn, E. A. P. Crowhart-Vaughan and Thomas Vaughan, ‘Introduction’, in Russia’s Conquest of Siberia: Three Centuries of Russian Eastward Expansion, vol. 1, Portland OR, Portland Historical Society, 1985, pp. xxxv‒lxx, see particularly pp. xl‒xli; ‘Documents Concerning the Expedition Led by Vasilii Poiarkov from Iakutsk to the Sea of Okhotsk’, in Dymytryshyn, Crowhart-Vaughan and Vaughan, Russia’s Conquest of Siberia, pp. 209‒217.

See, for example, Lee, The Russian Frontier in Ch’ing History, p. 14; Sasaki, ‘A History of the Far East Indigenous Peoples’ Transborder Acitivies’, pp. 167‒180.

Mamiya Rinzō (trans. and ed. John Harrison), ‘Kita Ezo Zutsetsu or a Description of the Island of North Ezo by Mamiya Rinzō’, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 99, no. 2, 1955, pp. 93‒117, citation from p. 116.

Yōchite acquired this name, which was written with the Chinese characters 揚忠貞 while in Manchuria. I use it here because it was the name by which he was commonly known thereafter. See, for example, Matsumae Hironaga, Matsumae Shi, reprinted in Ōtomo Kisaku ed., Hokumon Sōsho, vol. 2, Tokyo, Kokusho Kankōkai, 1972, pp. 97‒316, citation from p. 130.

Mamiya, ‘Kita Ezo Zutsetsu’, 107. Thie name ‘Yaepikarainu’ is my approximation based the Manchu version of his name, which was given as ‘Yabirinu’, and the Japanese version which was given as ‘Yaepikaran’, and the Ainu honorific naming convention of adding ‘-ainu’ to the end of the names of elders.

For example, a number of the Santan traders whom Japanese officials met in Sakhalin and Sōya in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were actually Ainu who had been taken to Santan territory, and important information that the Japanese collected about Manchuria came from these Ainu Santan traders; see Nakamura Koichirō, Karafuto Zakki, in Takakura Shinichirō ed., Saisenkai Shiryō, Sapporo, Hokkaidō Shuppan Kikaku Sentā, 1982, pp. 603‒650.

See Sasaki Shirō, ‘Shinchō no Amūru Shihai no Tōchi Rinen to sono Jitsuzō’, Hokutō Ajia Kenkyū, special edition no. 4, 2018, pp. 77‒99, citation from p. 92.

See Nakamura Koshirō’s account of his 1801 journey to Sakhalin – Nakamura Koshirō, Karafuto Zakki, reprinted in Takakura Shinichirō ed., Saisenkai Shiryō, Sapporo, Hokkaido Shuppan Kikaku Sentā, 1982, pp. 603‒650, citation from p. 619.

Mamiya Rinzō, discussing the position of hala-i-da as it was exercised by Yōchite’s son Yayenkur, observes that when Santan and Amur Nivkh travelled to Nayoro they were required to show their respect to the hala-i-da and, when they travelled around neighbouring villages, had to refrain from performing illegal actions; Mamiya Rinzō (ed. Minami Manshū Tetsudō Kabushiki Kaisha , Tōdatsu Kikō (1942 reprint), Tokyo, Manshū Nichinichi Shinbun Tōkyō Shibu, 1942, p. 78.

Sasaki, ‘Amūru Shimoryūiki no Shominzoku’, p. 707. ‘Ice’ in Manchu means ‘new’, and ‘hoton’ means a fortified village or town.

There are two somewhat different descriptions of Yōchite’s map. One, given by Matsumae Hironaga in 1781, gives the names of the ‘islands’ as ‘Icha, Botton, Sumukotamuru (a large island), Haaton, Suteya and Toshiri’; see Matsumae, Matsumae Shi, p. 130; the second, given by Mogami Tokunai in the 1790s, lists them as ‘Ichiyahots, Toresu, Makuta, Maru, Haatono, Suchiatoshiri etc.’; see Mogami Tokunai, Ezo Sōshi Gohen, reprinted in Ōtomo Kisaku ed., Hokumon Sōsho, vol. 3, Tokyo, Kokusho Kankōkai, 1972, pp. 450‒478, citation from p. 468. ‘Haaton’ or ‘Haatono’ may be a reference to the settlement of Haoton which, according to 18th century European maps, stood close to the site of the present-day city of Khabarovsk.

Yōchite continues to be listed in Manchu documents as hala-i-da of Yadan (Nayoro) until 1794, but Mogami Tokunai, who visited Nayoro in 1792, describes Yayenkurainu as being the region’s ‘headman’ [otona] at that time; see Matsuura, Shinchō no Amūru Seisaku, p. 110; Mogami, Ezo Sōshi Gohen, p. 468. Kondō Morishige, who collected information from Japanese officials who visited Sakhalin in 1801, includes as description of Yōchite’s tomb; see Kondō Morishige, Henyō Bunkai Zukō, vol 3, 1804 manuscript, Japanese National Archives, pp. 15‒16. This suggests that Yōchite may have handed over some of his de facto powers to his son by the early 1790s, and died during that decade.

The relationships between the generations are a little difficult to establish with certainty. Hara Tomio, after examining various sources, concluded that Setokurero was the son of Shirotoma, who in turn was the brother of Yayenkurainu and the son of Yōchite; see Hora, Karafuto Shi Kenkyū, pp. 146‒148; but Matsuura Takeshirō describes the Nayoro elder, whom he knew in the 1840s and 1850s (and who must have been Setokurero, though he does not name him there), as being the son of Yayenkurainu and the grandson of Yōchite. The most logical explanation is that the position of hala-i-da passed from Yayenkurainu to his brother Shirotoma because of the former’s failing sight, but then passed to Setokurero, Yayenkurainu’s son, who was thus the linear descendant of Yayenkurainu but the direct successor to Shirotoma. See Matsuura Takeshirō (ed. Yoshida Takazō), Sankō Ezo Nisshi, vol. 2, Tokyo, Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 1971, p. 222; also Umeki Takaaki, Saharin: Matsuura Takeshirō no Michi o Aruku, Sapporo, Hokkaidō Shinbunsha, 1997, pp. 132‒134.

Mamiya, ‘Kita Ezo Zusetsu’, p. 117; see also Ōtomo Kisaku, ‘Kaisetsu’ in Ōtomo Kisaku ed., Hokumon Sōsho, vol. 5, Tokyo, Kokusho Kankōkai, 1972, pp. 32‒33.

Walker, Conquest of Ainu Lands, p. 144; Akizuki, Nichiro Kankei to Saharintō, p. 38; Hora, Karafuto Shi Kenkyū, p. 66.

Akizuki, Nichiro Kankei to Saharintō, p. 29; see also Watanabe Kyōji, Kurofune Zenya: Roshia, Ainu, Nihon no Sangokushi, Tokyo, Yōsensha, 2010, pp. 260‒275.

Matsuda Denjūrō, Hokuidan, reprinted in Ōtomo Kisaku ed., Hokumon Sōsho, vol. 5, Tokyo, Kokusho Kankōkai, 1972, pp. 165‒166.

Schrenck, Reisen und Vorschungen, vol. 3, part 2, p. 623; Schrenck was quoting from Carl Friedrich Schmidt, who met Setokurero on a visit to Nayoro in 1860.

Leopold von Schrenck, quoted in Ravenstein, The Russians on the Amur, p. 271; see also Schrenck, Reisen und Vorschungen, vol. 3, part 2, p. 530.

See, for example, Sentoku Tarōji, Karafuto Ainu Sōwa, Tokyo, Shikōdō Ichikawa Shoten, 1929, p. 13‒14.

Suhara and Date’s northernmost fishing post was a village whose name is given as Haikaramushi or Haekarashamushi, close to the site of the present day city of Kholmsk. See Tajima Yoshiya, ‘Kinseiki, Meiji Shoki, Hokkaido, Karafuto, Chishima no Umi de Sōgyō Shita Kishū Gyōmin / Shōnin’, Chita Hantō no Rekishi to Genzai, no. 19, pp. 57‒78, 2015, citation from p. 65.

Tajima, ‘Kinseiki, Meiji Shoki’, p. 67; Akizuki Toshiyuki, ‘Kaisetsu’, in Nikolai Busse, trans and ed Akizuki Toshiyuki, Saharintō Senryō Nikki 1853‒1854: Roshiajin ga Mita Nihonjin to Ainu, Tokyo, Heibonsha, 2003, pp. 6‒40, citation from pp. 21‒22; Akizuki, Nichiro Kankei to Saharintō, pp. 248‒251; see also David Howell, Capitalism from Within: Economy, Society and the State in a Japanese Fishery, Berekeley, University of California Press, 1995, pp. 70‒71.

Hori Toshitada and Muragaki Norimasa, ‘Hori Toshitada Muragaki Norimasa Karafuto-tō Keibi Mikomisho’, in Okamoto Ryōnosuke ed., Nichiro Kōshō Hokkaidō Shikō, Tokyo, Fūgetsu Shoten, 1898, Part 3, pp. 3‒8.

Matsuura, Sankō Ezo Nisshi, vol. 2, p. 173; see also Hanazaki Kōhei, Shizuka na Taichi: Matsuura Takeshirō to Ainu Minzoku, Tokyo, Iwanami Shoten, 1993, p. 93.