Abstract: Nominally fought over competing interests in Korea and Manchuria, the Russo-Japanese war had a significance that far outweighed its strategic reach. Central to its legacy was its outcome – the defeat of an old European Great Power by an aspiring non-European imperial state. This outcome inspired a great deal of racial and geostrategic introspection, whilst intensifying concerns in the West about ‘Yellow Peril’ that would one day overthrow European dominance. This article argues that the impact of the Russo-Japanese War on racial thinking in Japan was as significant as it was abroad, to the extent where the conflict was understood by key intellectuals as nothing short of a race war. These figures, including political philospher Katō Hiroyuki, historians Taguchi Ukichi and Asakawa Kan’ichi, and biologist Oka Asajirō, identified the outcome of the conflict as evidence that the established Eurocentric hierarchy of races was wrong. Japan’s success, they argued, showed that the Japanese race (distinct, it should be noted, from other Asians) was at least on a par with their white rivals. Furthermore, some argued that it was in fact the Russians who should be excluded from the upper echelons of the racial hierarchy. Their work reveals the profound impact of the events of 1904-1905 on Japanese self-perception and confidence – and reveals the roots of racial attitudes that continue to bedevil the nation in the 21st century.

Keywords: Race, social Darwinism, Russo-Japanese War, Russia, Japan, Meiji, biologism, racism.

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 was a conflict of firsts. At least a decade in the making, hostilities between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan commenced with a surprise Japanese attack on the Russian Far East Fleet at Port Arthur in the 8th of February, 1904. In the following 18 months, the world witnessed the first use of wireless communications in a war, the first engagement between fleets of steel battleships on the high seas, the first extended period of trench warfare, and the first Japanese occupation of Seoul. By the end of the war, after bloody engagements at Port Arthur, Sandepu, Mukden, and Tsushima, observers were presented with yet another first: the defeat of a European colonial power by a non-European foe. It is the last of these ‘firsts’ that provides the central theme of this paper. The defeat of a white, European power by a non-white, Asian power had powerful resonances not only in Japan, but across the world. To a significant element within the Japanese intelligentsia – men with public and official influence – the Russo-Japanese war was, put simply, a race war.

The Japanese were not unique in this outlook – there were plenty of racial explanations for the origins of the conflict in the West. However, the preoccupations of Japanese intellectuals in this sphere were distinct and unique. The Russo-Japanese conflict was understood by these figures as a revolutionary commentary on the hierarchy of races – a social Darwinian systematization that had long held that humanity could not only be divided into races, but that some (Anglo-Saxons and Germanic folk usually) were superior and destined to out-compete the others. As this paper explores, these Japanese racial theorizers accepted as given two fairly uncontroversial (at the times) positions of the racial hierarchy thesis. The first was that the political state (kokka), the ‘people’ (kokumin) and ‘race’ (jinshu) were inseparable; ‘race’ equalled ‘people’, who in turn generated ‘state’. The second was derived from a world view that based its analytical framework on biological and Darwinian paradigms which posited that one of, if not the, ultimate driving force behind international confrontation was the competition between races. These, however, were then deployed by Japanese thinkers to critique key elements of the racial hierarchy as understood in the West. The Japanese were not unequal to the white races, they argued, indeed, they were in some ways superior. Some argued that underestimation of Japanese abilities was a fundamental flaw in the European outlook; others that the Europeans were essentially correct, but it was not the Japanese who were ‘Mongoloid’, rather it was the Russians. Either way, all the figures discussed here argued that the conflict of 1904-1905 was a race war that was settled in Japan’s favour – and in doing so had upended the conventional hierarchy of race.

Global Perceptions: The End of the ‘White Race’s Dominion’

In the hundred years or so since the end of the Russo-Japanese conflict in the Treaty of Portsmouth, several historians have emphasized that for all the perceived significance of the conflict, it was, in practical terms, a somewhat limited affair (Steinberg 2008:2). Militarily, it was far from a cataclysmic total war in which Japan utterly vanquished the Russians; as Naoko Shimazu has astutely observed, ‘The only way the Japanese state could realistically win against Russia…was to engage in a limited war, fought for limited objectives, in line with limited national capabilities’ (Shimazu 2009:4). Most historians have argued that rather than being a transformative moment in the East Asian political balance, it is best understood as a step in a longer trajectory of imperialism and capitalism (Shimazu 2009:4; Wilson 1999:160-161). As Katō Yōko puts it, ‘by regarding the Russo-Japanese War as…a war waged to establish Japanese control over Manchuria, the Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War have come to be seen as sequential steps. This way of thinking fits the Russo-Japanese War into position…as a gauge for displaying the development and progression of Japanese capitalism’ (Katō 2007:97).

Nevertheless, given both contemporary and subsequent interest in the conflict outside of East Asia and Russia, perceptions of the war are worth looking at in detail. As Katō points out, the European colonial powers were intimately connected with the events of the conflict. (Katō 2007: 95-6, 99-101). As Steinberg has observed, ‘While the international community strove to maintain neutrality throughout the war, all of the European powers were implicated in one fashion or the other because of treaty obligations to either Russia or Japan’ (Steinberg 2008:5-7). The 1902 alliance with Britain, for example, was crucial in giving Japan the confidence to engage in hostilities with a nation in possession of the largest land army in the world without provoking the intervention of its French allies (Yamada 2009:218-230), whilst American and British loans to the tune of some $200 million bolstered their military capabilities. Furthermore, the rise of ‘transnational and international organizations such as the Red Cross’ adds a further international dimension to the war, which provides a rich avenue of inquiry for future historians.

Furthermore, regardless of its geopolitical limitations, the Russo-Japanese War was perceived as important across the world at the time. Indeed, the second of two centennial conferences on the 1905 conflict held in Japan bore the title ‘World War 0: Reappraising the War of 1904-5’. As Katō Yōko observes, participants ‘wanted to include China and Korea in a constructive way because conventional research on the war lacks the viewpoints of these two countries, even though the war was fought in Korea and Manchuria.’ This sense that the Russo-Japanese war was far more than a Russo-Japanese affair was certainly pervasive during the conflict itself, when many across the world ‘paid close attention’ to the events in what was then dubbed the Far East. Indeed, no sooner had ‘fighting erupted on the Pacific in February 1904’ than ‘military attaches, journalists, and other observers from Europe and North America flocked to the front. Already within months illustrated volumes began to appear to satisfy the public’s appetite for news about the combat’ (Van der Oye 2008:81). News of Japan’s victories at Port Arthur and Mukden spread rapidly across much of colonial South East and South Asia (Yomiuri Shinbun Shuzaihan 2005:137), and inspired ‘a group of worthy American ladies…to host a tableau-vivant to collect donations for the relief of Japanese families of soldiers’ (Shimazu 2009:1).

Many of these people understood the conflict as being not merely strategic and geopolitical but civilizational in nature. As Shimazu puts it, ‘the war fueled the imagination of international contemporaries, representing many iconic clashes: the West versus East, Europe versus Asia, Christian versus “heathens”, tradition versus modern, and the white race versus the yellow race’ (Shimazu 2009:1). Perhaps the most striking visual representation of this outlook is Hermann Knackfuss’s famous 1895 lithograph Völker Europas wahret eure heiligsten Güter, known in English as ‘The Yellow Peril’ (Fig.1).

Fig. 1. Völker Europas wahret eure heiligsten Guter (‘People of Europe, Protect Your Most Sacred Goods’ aka ‘The Yellow Peril’). Hermann Knackfuss, 1895. Represented as the defenders of Christendom are France, Germany, Russia, Austria, Italy, and Great Britain.

Fig. 2. A lesser-known caricature from five years later by Johann Braakensick, subtitled ‘People of Asia, Protect Your Most Sacred Goods’, inverts the image, showing China in arms on the eve of European invasion.

In the West, Japan’s successes came at a time of increasing anxiety about declining birthrates (Connelly 2008:20) and an inevitable war between the ‘yellow’ and ‘white’ races for dominance of the globe. The war was seen as a herald of a new age of racial conflict, and one which held a warning for whites. American war correspondent Murat Halstead commented in 1906 that it had been a ‘logical war’ and ‘wondered, among all the colossal eventualities that the war might lead to, whether Europe might conquer Asia, or Asia would conquer Europe’ (Shillony & Kowner 2007:1).

Underlying this was a distinctly Social Darwinian view of race relations, which posited that Spencerian ‘survival of the fittest’ would dictate the ’progress’ of races in the world (Spencer 1975 [1857]:39-52; Spencer 1870:445-449). Crucially, however, many contemporary observers pointed out that ‘fittest’ did necessarily mean ‘better’. Indeed ‘fittest’ ‘meant only those who could subsist on less and reproduce more.’ Hence as far back as 1877, the special US House-Senate committee could argue that though ‘the Chinese lacked sufficient “brain capacity” to sustain self-government, they could survive in conditions that would starve other men’ (This fear of being ‘outbred’ by the Chinese had resulted in a halting of immigration from the country to California in 1882 and sparked anti-Chinese pogroms). (Connelly 2008:33-42).

To the Russians, however, ‘Yellow Peril’ narratives were associated almost ‘exclusively with Japan’, particularly after the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895 (Bartlett 2008:13). At stake was nothing less than the salvation and civilization of the East. Explorers such as Nikolai Przhevalskii, who travelled extensively in the Russian Far East, equated ‘Russian imperialism with Western civilization’ and saw the extension of Russian power into the area as a sort of civilizing mission (Bartlett 2008:13; Westwood 1986:5). Sergei Witte, architect of Russia’s Far East policy during the 15 years preceding the war, viewed the Russians as a ‘European race’ and asserted that ‘Russians brought enlightenment to the Orient’ by ‘extending Europe eastward’ (Westwood 1986:4; Zachmann 2007:37). Witte presented the war ‘as a confrontation between Asia and Europe. Russia claimed to be the eastern outpost of Christendom, guarding Western civilization against yellow, heathen hordes’. Defeat in the conflict was seen as ‘threatening Russian and European civilization generally’ (Bartlett 2008:25) and caused ‘grave anxiety’ amongst ‘all those who believe[d] in the great commercial and civilizing mission of the white race throughout the world’ (Shillony & Kowner 2007:7). Non-Russians often concurred – upon ‘learning of Port Arthur’s fall to the Japanese in January 1905, a German naval officer gloomily noted in his diary that “the white race’s dominion has run its course”’ (Van der Oye 2008:83).

Perhaps the most striking reception of the Russo-Japanese war was in countries under the yoke of, or threatened by, colonialism. As Steinberg puts it, ‘the victory of the Japanese forever transformed the image that people of colour, the colonized people of the world, had of their Imperial masters. Japan’s victory started them down the road of creating Asia for the Asians’ (Steinberg 2008:4; Van der Oye 2008:82) – a sentiment all the more interesting because the Japanese were not amongst the colonized peoples of the world. Amongst those inspired by Japan’s victory were Yuan Shikai, Jawaharlal Nehru (Toyoda 2009:386-387), and Rabindranath Tagore – who, upon hearing of Japan’s victory, ‘paraded around the grounds of his school, Santiniketan, with his students’ (Shimazu 2009:3). Similarly positive responses, predicated on the idea of the undermining of white dominance, were also forthcoming from Ho Chi Minh (Yomiuri Shinbun Shuzaihan 2005:127-138) and African-American activist Mary Church Terrell, who observed that the ‘victory of Japan in the Russo Japanese War has buried the dominance of the white race’ (Yomiuri Shinbun Shuzaihan 2005:82).

Japanese Intellectuals: Public Work and Global Consciousness

Despite the extended coverage of this sort of narrative outside of Japan, there has been somewhat less exploration of racial narratives in Japanese responses to the Russo-Japanese war. It is notable that in the Japanese scholarship, overviews of the conflict contain minimal discussion of this racial worldview, with many historians concentrating instead on proximate geopolitical causes such as the ‘Korea Question’ and the exploitation of Manchuria (see YSS 2005; Toyoda 2009; Yamada 2009). Others have tended to explore writings on the conflict within the context of an individual’s body of work, rather than as a broader intellectual discussion. Hence notable exceptions to the racialized view of the Russo-Japanese War have been explored in some detail. These included leading left-wing activist Kōtoku Shūsui, who maintained a relentless critique of the Russo-Japanese conflict throughout 1904 and 1905 through his mouthpieces Heimin Shimbun and its successor Chokugen (Shimazu 2008:37, 2009:35). The ‘global vision’ of the left characterized ‘their struggle in Japan as but one component of the global struggle of socialism against capitalism’, and the Heimin Shimbun’s eventual declaration of sympathy for Russia’s working classes was consistent with the leftist view that it was class, and not race, that mattered most (Shimazu 2008: 38; Wilson 1999:168-175; YSS 2005:48). Furthermore, Christian writers such as Uchimura Kanz also expressed grave reservations about the conflict and did not present the war as racial in origin (YSS 2005:45).

However, many intellectuals did articulate opinions that display at least some of the racial themes described above, and it is on the writings of these individuals that this paper will focus. These were significant for two reasons. The first is that the writings produced by certain intellectuals had a powerful influence on public perceptions of the conflict, and they can hence be reasonably be called ‘public’ intellectuals. As Robertson has pointed out in connection with eugenics, for example, the ‘popular’ and the ‘scientific’ ‘did not inhabit opposite ends of a spectrum of credibility’ (Robertson 2002:192). Indeed Nagayama has pointed out that literary publications such as Taiyō and Chūō Kōron, both of which ran articles on the Russo-Japanese War, had a great deal of public credibility, and helped shape a ‘turning point’ in the public’s engagement with published materials (Nagayama 2007:74-75). The work of people like Oka Asajirō, Katō Hiroyuki, and Takahashi Yoshi found a readership far beyond that of colleagues and specialists; their musings are thus significant in that they were read, distributed, and discussed by the population at large at a time when comprehending and explicating the events of the war were of the essence to many.

Second, many of those under discussion bridged not only the intellectual and popular within Japan, but also Japan’s intellectual world with the global intellectual milieu. Taguchi Ukichi was a leading proponent of international free trade and liberal economics; Katō Hiroyuki was amongst the first German speakers in Japan and engaged extensively with the writing of European thinkers such as Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, Edward Gliddon, Josiah Nott, the Comte de Gobineau, and the Comte de Buffon; Oka Asajirō’s professional intellectual training was in the distinctly European tradition of evolutionary biology. Both Sherrie Cross and Yoshida Hiroji have pointed out that Katō, and possibly Oka, were influenced heavily by the deterministic biologism of Edward Sylvester Morse1 (Cross 2009:334-344; Yoshida 1976:54). Perhaps most striking here is the example of Asakawa Kan’ichi – who received his PhD from Yale in 1902, and was the first Japanese appointed to the faculty there. His 1904 The Russo-Japanese Conflict was written in English specifically for an international audience, providing an interesting example of counter-flow between the Japan and the ‘west’.

Civilization as Race and Race as Competition

One of the most important predicates of the racial worldview was a conflation of civilization, state, and race. It was on this basis that Japanese intellectuals at this time explicated the Russo-Japanese War as a clash of races. Naoko Shimazu, for example, has identified two distinct Japanese narratives in response to the Russo-Japanese War. The first was a ‘civilizational discourse’ which stated that Japan was fighting Russia to save ‘civilization’. Another ‘pitched the war as a war of races, in which Japan was a yellow race fighting against the white race’. Crucially, however, ‘one cannot ignore the strong undercurrent of racial animosity and hatred towards the enemy that existed even among those who subscribed to the “civilization” discourse’. Hence the ‘civilization’ and ‘race’ narratives can be seen as ‘representing two different sides of the same coin’ (Shimazu 2009:160). Historian Shimada Tako concurs, observing that racial animosity underlay the ‘issue of the qualitative difference of culture and civilization’ (Shimada 2007:284). Further ensuring the elision of these ideas was the fact that though concepts such as ‘nation’ and ‘race’ are now denoted in Japanese by distinct terms such as minzoku and jinshu, the semantic content of these terms were more fluid in the early 20th century, and they were sometimes used interchangeably (Robertson 2002:192).

This conflation of race and civilization found a powerful expression in Japan in the concept of ‘family-state’ (kazoku kokka) which gathered increasing strength throughout the late 19th and early 20th century. In essence the concept ‘stretched out the family metaphor and likened nationality to membership in an exceptional “bloodline” (kettō)’ (Robertson 2002:192). Amongst its most vocal supporters was Katō Hiroyuki, who held to the biological nature of culture and civilization so intensely that he worried that any alteration in the former would lead to the utter destruction of the latter. In 1884, Takahashi Yoshio suggested in his ‘Treatise on the Improvement of the Japanese Race’ (Nippon jinshū kairyō ron), that the offspring of Japanese men and white women would be capable of more ‘civilized’ behaviour than their ‘pure-bred’ Japanese counterparts (Takahashi 1961 [1884]: 24, 29).2 Katō argued against this in his response, ‘On Improving the Japanese Race’ (Nippon jinshū kairyō no ben) that altering the racial makeup of a people could result in disastrous hybridization. The new, mixed-race breed would be unable to fit into the civilization and culture of either of their parents, causing suffering for them and the nation. Such an outcome had already occurred, he argued, in places such as Peru; Japan should avoid it at all costs (Katō 1886: 27-48).

Non-Japanese observers of the Russo-Japanese war – amongst whom were a small army of British military attaches such as Sir Ian Hamilton – frequently equated Japan’s success to ‘the Warrior Spirit of Japan’ (Van der Oye 2008:82). Japanese observers did the same – notably in Asakawa Kan’ichi’s 1904 The Russo-Japanese Conflict. Asakawa’s work presents a nuanced take on the crisis, and his conflation of race and civilization is subtle. Asakawa’s objective with the work, which was published in New York soon after the commencement of hostilities, was to present an erudite English-language explication of Japan’s position on the war to his western colleagues. Japan’s quarrel with Russia was the inevitable consequence of Russian intractability over the issue of who should control Manchuria (Asakawa 1904:1). Yet the prime cause of this was nothing less than ‘a dramatic struggle between two civilizations, old and new, Russia representing the old civilization and Japan the new,’ (Asakawa 1979 [1904]: 53, 39). Furthermore, biology – in Asakawa’s parlance, ‘nature’ – underlay the basic geopolitical circumstance of the conflict. His explanation of the ‘unnatural’ circumstances of the ‘old’ Russian polity is worth quoting at length, deftly mixing as it does geography, politics, and biologism:

Similarly, Asakawa argues that the inhabitants of Korea and China are, as a result of their inherent deficiencies, capable of resisting neither the rapaciousness of the Russians nor the ‒ justifiable ‒ civilizing mission of the Japanese. Koreans, Asakawa argued, ‘lack the energy to cultivate’ marginal land, resulting in their relatively low population, and the necessity for Japanese management of their resources (Asakawa 1904:27). The Japanese themselves were reducible to a single, unified whole, and the conflict with Russia is taken as a challenge to the ‘moral force’ of the Japanese nation (Asakawa 1979 [1904]:372).

Echoing this view of civilization as an expression of the underlying capacity of populations is the work of Nakata Minoru, a journalist active throughout the Meiji period under the pen name Kuga Katsunan. Born ten years before the Meiji Restoration, Kuga studied French and adhered to a romantic nationalism that led him to resign from what he saw as an overly Westernising Meiji government in 1888 and turn to journalism. From 1889, he wrote extensively in his own publication Nippon. He was nothing if not prolific – between the 1st of January 1904 and the 31st of December 1905, Kuga published 253 articles on a variety of subjects (Kuga 1972 [1904-1905]: vii – xiv). Much of his writing argued that Japan represented ‘civilization’ in opposition to Russia’s ‘anarchism’ and degeneracy, and that these qualities were inherent to the peoples of both nations. Russia, Kuga argued, was fundamentally an ‘anarchic country’ (Rokoku wa tsune ni hansenji no kuni nari) (Kuga 1979 [1904]: 243-244). In an article published the day after the declaration of war, Kuga casts the events of the preceding day explicitly as the expression of the will of the entire Japanese populace ‘because the objective of the Japanese people [Nihon kokumin] is to promote peace in east Asia and preserve the integrity of China’ – and indeed, rather than being afraid of Japanese ambition, ‘the people and government of China should be most grateful’ (Kuga 1974 [1904]:244). Kuga’s opinion here had roots going back at least to Japan’s earliest imperialist missions in Taiwan, in which the failure of aboriginal Taiwanese to create a ‘civilization’ was taken to mean not only that they were incapable of doing so, but that it was then entirely justifiable for the ‘civilized’ Japanese to take possession of their territory and resources, according to the rules of evolutionary competition (Eskildsen 2002:391). Furthermore, just as Asakawa argued that civilization manifested from nature, Kuga posited that nature could be divined through civilizational behaviour. ‘True civilized thought does not view barbaric actions as justifiable,’ he opined. ‘Consequently, it does not view countries which commit barbaric acts as civilized. Consequently, considering how the great [European] powers lately acted in East Asia, the powers are not civilized countries, but barbaric countries’ (Kuga 1979 [1904]: 137; Zachman 2007:23).

The view that civilization is a product of underlying biological factors is discernible in the work of evolutionary biologist Oka Asajirō – one of the most influential thinkers on issues of race and civilization in Japan. Born one year before the Meiji Restoration, Oka spent time studying in Germany, and adhered to a ‘monist’ evolutionism which explicated nearly all aspects of human cultural and political life ‘on the basis of Darwinism’ (Shimao 1981:96). His Summary of Evolution (Shinkaron kōwa), published soon after the eruption of Russo-Japanese hostilities in 1904, was the first attempt at introducing Darwinian evolution and social Darwinism to the general reading public. The book provides a comprehensive overview of evolutionary theory from the work of Charles Lyell through to that of Darwin’s successors, Herbert Spencer and Francis Galton. Towards the end of that work, Oka produces separate sections on the relationship between evolutionism and philosophy, education, society, and religion (Oka 1974 [1904]: 256-276). ‘Evolution has an extraordinary influence on all human ideas’ argues Oka, precisely because it ‘indicates the basic truth’ of human development (Oka 1974 [1904]:277).

Katō Hiroyuki, former president of Tokyo Imperial University, was another notable intellectual who publicly espoused such views. A legal and political theorist by training, Katō was originally part of the ‘natural rights’ movement agitating for popular representation, and his intellectual influence reached the highest echelons of the Meiji state – from 1870 to 1875 he was a tutor to the Meiji Emperor himself (Davis 1995: 13). By the time of the Russo-Japanese War, he was one of Japan’s foremost public intellectuals (Katada 2010: 3-5, 16; Tabata 1986:17-18). Though nominally in an entirely different discipline, Katō’s intellectual heritage was akin to Oka’s; his ‘political naturalism’ was heavily influenced by the social Darwinistic theorising of Spencer and Galton, Darwinism, and progressivism (Yoshida 1976:71). Indeed, Katō was personally acquainted with Edward Sylvester Morse during the latter’s time in Japan (Cross 2009:336-337). It should thus come as no surprise that in his 1904 ‘Observations of Future Russo-Japanese Relations from an Evolutionary Perspective’ (Shinkagaku yori kansatsu shitaru Nichiro no unmei), Katō would argue that Japan would undoubtedly emerge victorious from the current conflict because it boasted the more ‘evolved’ polity – a homogenous state, united under the tennōsei system (Katō 1904). The biologism of this position was further explored by Katō in his 1912 Logic and Nature (Ronri to shizen), where he posits, not unlike Oka, that human organization is essentially a biological process. The sophistication and success of these organizations depend on the biological characteristics of those organizing. ‘Barbarians’, when they do organize, do so in a manner more akin to ‘herds’ (Katō uses the German term schwarm) (Katō 1990 [1912]:517), but when truly evolved ‘third level’ creatures such as humans organize, Katō argued, the result is a ‘state’ (dai san dankai yūkitai taru kokka). This ‘moral and philosophical naturalism’ was an inherent part of Katō’s thinking from at least the 1870s (Davis 1995: 13). It is interesting to note here that Katō’s emphasis on the likeness between ‘uncivilized’ humans and animals is an echo of Darwin’s own tendency to ‘always see continuous gradations “between the highest men of the highest races and the lowest savages”’, and between the ‘lowest savages’ and animals – a view that led him to ‘close any gap in intelligence between Fuegians3 and the orang-utan’ (Paul 2009: 218).

Concerns in the Western world about the populousness of other races is a weed with deep roots. Even Benjamin Franklin once observed that ‘The number of purely white People in the world is proportionately very small…I could wish their Numbers were increased…I am partial to the Complexion of my Country, for such Kind of Partiality is natural to Mankind’ (Frankin: 1761). By the time of the Russo-Japanese War, the Russian Empire too had become consumed by such concerns, and fully participated in the notion that racial conflict posed no less profound a question than ‘who shall inherit the earth?’ (Connelly 2008:6-7). From the Russian perspective, there were those such as academic Ivan Sikorskii who believed Siberia and the east was ‘a “battlefield for the future racial struggle” between Russians and Japanese’ (Zachman 2007:54). The fact that Sikorskii was a Darwinist provides some sense of the linkage between social evolutionary thought and a racial worldview.

The idea that competition between humans, individually and in groups, is biologically determined is clearly present in Oka Asajirō’s Shinkaron kōwa. Early on in the work, Oka presents competition as one of the driving forces of natural adaptation, identifying ‘competition between dissimilar kinds’ (ishukan no kyōsō) and ‘competition within species’ (dōshunai no kyōsō) as two of the most basic modes of interaction in nature (Oka 1974 [1904]:61-67). Oka is explicit that what applies to animals also applies to humans. In his own colourful turn of phrase, ‘There are no points of basic difference between humans, dogs, and cats’ (ningen to inu, neko no aida ni wa, konhonteki ni chigatta ten wa hitotsu mo nai) (Oka 1979 [1904]:241,244).4 He later emphasizes bluntly that ‘humans are a variety of beast’ (hito wa jūrui no isshu de aru) (Oka 1974 [1904]: 248). As mentioned above, this sort of competition is not limited to humans living in a state of nature prior to the emergence of organized politics and societies. To the contrary, this urge to compete is one of the underlying factors in the emergence of more complex sociopolitical organizations. Given that contemporary science posited that races were a ‘natural’ means of differentiation, it follows that competition between races was an inherent part of race relations.

The writing of Asakawa Kan’ichi also adheres to the same logic of conflict as an essential feature of relations between peoples. As mentioned above, Asakawa viewed the Russo-Japanese war as an encounter of civilizations. That conflict was an essential part of such is a theme that recurs in The Russo-Japanese Conflict, and is stated most explicitly in Asakawa’s discussion of Japan’s rising status amongst world powers. In his view, Japan’s ‘new position…in the Orient’ was acquired at least partly through her ‘victory over China’, which is in and of itself a relatively uncontroversial observation. Such conflicts were essential in order to prove that Japan could ‘compete with the greatest nations, not only in the arts of peace, but also in those of war’ (Asakawa 1979 [1904]:79-80) – and the ability to succeed in these arenas was determined by the racial makeup of the Japanese state. Arguably, the connection between Asakawa’s views here and the racial world view is somewhat indirect; any scholar wishing to situate such observations must keep in mind the previously mentioned conflation of civilization and racial characteristics, as well as Asakawa’s notion of a ‘clash of civilizations’, in order to do so.

The Hierarchy of Races

As shown above, key Japanese public intellectuals understood and explicated the Russo-Japanese War through the lens of race. The implications of Japanese victory were hence both geostrategically and intellectually profound. Nowhere was this more the case than in discussions of one of the mainstays of contemporary racial theory: the hierarchy of races.

The Japanese themselves were keenly aware of ideas about this hierarchical relationship as far back as 1874. One historian has observed that ‘Japanese efforts to appropriate and adapt Western ideas about power and hierarchy pervaded Japanese society at the time’, as did an awareness of the ‘close link between civilization and a global order of nations’ (Eskildsen 2002:390, 392). Katō Hiroyuki and his contemporaries generally accepted five-fold divisions of race, such as German naturalist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach’s system of Caucasian, Mongolian, Malayan, Ethiopian, and American races (Katō 1886:6-7). There was also an awareness of the fact that the Darwinian biologization of civilizational difference held profound implications for the position of the Japanese within the racial hierarchy – as Unoura puts it, ‘Japanese acceptance of Darwinian theory was characterized by their feeling of racial inferiority towards Caucasians’ (Unoura 1999:238). The ‘middle’ position of the Japanese race, for example, forms one of the key elements of Katō’s pushback against suggestions of racial admixture in the 1880s (Katō 1886: 1-17).

These views were, perhaps inevitably, popular in the West. Whilst admiring Japan’s economic and political progress, many white observers were keen to emphasize the moral and cultural superiority of the white race over the ‘yellow’ race. Iikura Satoshi, for example, has traced the existence of what he calls ‘paternalism’ (pataanarizumu) in coverage of the Russo-Japanese war in Europe and America, which emphasized the childishness of the Japanese despite acknowledging that Japan had gone from being a ‘regional power’ to a ‘militarily strong country’ (gunji choukoku) (Iikura 2005:229). In Russia, there was a similar belief in the superiority of their own martial and organizational ability, expressed by the contemporary notion amongst Russian leaders that Port Arthur could be held ‘with one sentry and a Russian flag’ (Bartlett 2008:16). This was not due to ignorance on the part of the Russians about Japanese culture – on the contrary, ‘by 1903 Russia was flooded with books and articles about diverse aspects of Japanese culture and society’ (Bartlett 2008:22). Despite this, a powerful sense of Russian superiority pervaded many responses to the conflict. For example, Alexander Benois, a Russian intellectual of some repute, responded to the declaration of war as follows:

Japanese thinkers had pushed back against such attitudes with vim since at least the 1870s. This racial anxiety resulted in attempts prior to the Russo-Japanese war to challenge the implication that the Japanese were inherently inferior. On the one hand, certain intellectuals took to praising ‘Yamato’ blood, arguing that the Japanese were perfectly capable of competing with the white race as equals (Wagatsuna & Yoneyama 1967:127). On the other, many Japanese writers attempted to distance the Japanese from their ‘yellow’ neighbours in Korea, China, and in particular Taiwan – as Eskildsen puts it, by ‘evacuating’ the ‘middle ground between civilization and savagery’ (Eskildsen 2002:399). Through this process, Japanese thinkers and authorities emphasized the differences between themselves and their Asian neighbours. The latter were characterized as backward, under-developed, and ultimately in need of the same guidance Western powers were providing in their own colonies. Japan, on the other hand, having more in common with said imperial powers, was the natural provider of such paternalistic care – even if sometimes this had to be imposed by force.

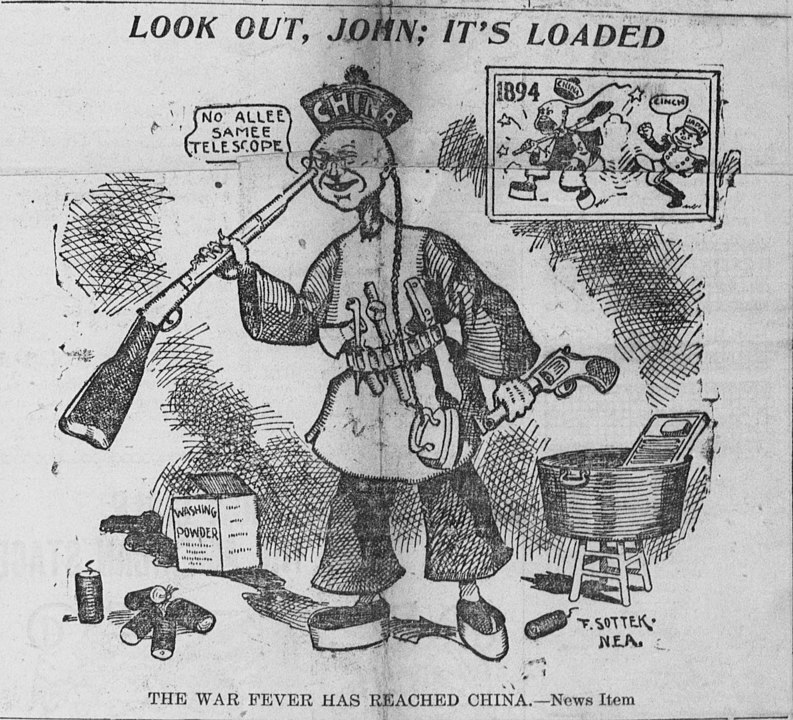

Fig. 3. The War Fever Has Reached China. Frank Sottek, 24th January 1904, The Tacoma Times. Racist characterizations of Asians during the Russo-Japanese War occasionally bought into distinctions between the Japanese and Chinese that the Japanese themselves were keen to propagate. In this 1904 cartoon a hapless ‘Johnny Chinaman’ reveals his ignorance of modern weaponry, while the reader is reminded of his humiliating defeat by the Japanese in 1895.

At the same time, there were those who cast doubt on Russia’s position within the former group of civilized nations – and went so far as to propose that Russians were in fact not ‘white’ at all.5 The most vocal proponent of this view was Taguchi Ukichi. Taguchi combined a commitment to free-market capitalism with historical romanticism and a strong sense of the ‘progress’ of civilizations; his work had two key intellectual anchors. The first was the notion of progressivism. His 1902 book 19th Century Trends and the Future (Jū kū seiki no taisei oyobi mirai), for example, drew on examples from British history to argue that much of 19th century history had been the story of the ‘expansion of freedom and rights in all countries’ (kaku kuni minzoku no jiyū oyobi kenri wo shinchō) (Taguchi 1928 [1902]:456-459). Second was the idea of social Darwinism, based on a re-interpretation of the work of Thomas Malthus. Malthus had argued that natural limitations depressed birth rates of ‘lesser’ groups of people – such as the poor and destitute – whilst falling more lightly on more competitively fit groups, such as the aristocracy (Taguchi 1928 [1902]). Following proposals written for the Meiji government about the war (Taguchi 2000:175-186, 280-282), Taguchi published two articles in Tōkyō keizai shimbun on the issue of race and the Russo-Japanese War. The first of these, appearing in the 16th April edition, was entitled ‘What is the Yellow Peril?’ (Kōka to wa nanzoya). Taguchi’s response was simple: it is Russia. As a populace once dominated by that most famous vision of ‘yellow’ rapaciousness and despotism, the Mongolians (dubbed datsutanjin6), the Russians had become racially mixed. Taguchi extends his argument in his 1904 Against the Yellow Peril (Hakōka ron) in the section ‘Russians are a Mongoloid Race’ (Rōjin wa datsutan jinrui nari) (Taguchi 1928 [1904]:497-498). Quoting the work of British writer Donald Wallace Mackenzie, Taguchi posits that, because their population had been subject to the influence of various eastern peoples such as the Huns (annu or kyōdo7), ‘Mongoloid blood’ had gone so far as to ‘enter Russia’s royal family’. Certainly by the end of the domination of the Volga basin by the datsutanjin, most of the Russian nobility had become ‘mixed’ (konnyū) with ‘Mongolian blood’ (Taguchi 1928 [1904]:497). As a result, their behaviour ‒ relentless expansion, prolific reproduction, and general low level of organization ‒ was far more in keeping with the characteristics of the ‘Yellow Peril’ than the Japanese (Taguchi 1928 [1904]:485-486, 497-500).

At the same time, there were also those who attempted to distance the Japanese as a racial group from characterizations of ‘yellowness’ and to find some underlying commonality between them and that most ‘advanced’ of white racial groups, the Anglo-Saxons. This notion of ‘leaving’ Asia had been popularized as early as 1885 by Meiji luminary Fukuzawa Yukichi in his famous Treatise on Leaving Asia (Datsu-A Ron) (Fukuzawa 1885). By the Russo-Japanese War, ‘Japanese obsession with the Yellow Peril, which reflected mostly on their own sense of insecurity as a non-white “great power”, meant that many wartime pundits were principally concerned with arguing that Japan did not constitute the Yellow Peril for one reason or another’ (Shimazu 2009:161). This is reflected, for example, in the emphasis in the accounts of many Japanese soldiers during the Russo-Japanese war on the ‘filth’ of Chinese and Korean dwellings, and the distinction between the Japanese and ‘dojin8’ – inhabitants of Manchuria, here denoted by a term that roughly means ‘aborigine’ (Shimazu 2009:7-8). Intellectuals adopted similar themes in their writing during the Russo-Japanese War, in particular emphasizing commonalities between the Japanese and their Anglo-Saxon counterparts. Asakawa Kan’ichi, for example, was explicit in aligning the interests of the ‘Anglo-Saxon nations’ and Japanese in The Russo-Japanese Conflict. The ‘evolution’ of Japan’s ‘interests at home and abroad seems’, he argues, ‘by a fortunate combination of circumstances, to have…[drawn] her and the Anglo-Saxon nations closer together’ (Asakawa 1979 [1904]:81). Indeed, recent history had shown (in Asakawa’s view) that Japan had ‘joined the circle’ of Anglo-Saxon civilization (Asakawa 1979 [1904]:55). The implication here is quite clear; if Japan were a member of this putative Anglo-Saxon civilization, this not only placed it on a par with other ‘civilized’ nations such as Britain and the US, but also excluded Russia from the group by virtue of its conflict with Japan. The hierarchy is thus subverted at the expense of Russia.

Taguchi Ukichi also weighed in on this, but in more explicitly racist terms. In addition to the aforementioned What is the Yellow Peril, Taguchi also wrote and published two further opinion pieces in the Tokyo keizai zasshi in 1904 – ‘The Japanese Are Not a Yellow race’ (Nihon jinshu wa kōjin ni arazu) and ‘The Japanese Should Be Regarded As an Aryan race’ (Nihon jinshu wa ariyan gozoku ni zokusuru mono nari); the latter of these was included as part of his Against the Yellow Peril Theory (Hakōka ron), completed the same year. The titles of these pieces alone make Taguchi’s position clear. Referring to the ancestors of the Japanese as tensonjin9, Taguchi asserts that ‘the tensonjin were white’ (tensonjin wa shiro iro nari), and that the Japanese race and the tensonjin are both ‘excellent’ races (yūtō jinshu). His logic leads him inexorably to his ultimate claim, that ‘inferring from the fact that tensonjin were of the same race as the Sanskrit [sic] and Persian races, linguists say [the Japanese] can be said to belong to the Aryan race’ (Taguchi 1928 [1904]:496-497). It is on this basis that Taguchi makes his interesting claim that the Japanese and Hungarians are, judging from linguistic similarities, both ‘beautiful white races’ (Taguchi 2000:296-298). Taguchi’s views both reflected and inspired similar attitudes amongst the Japanese public. Even some members of the clergy concurred – in 1904 Buddhist monk Ōchi Seiran publicly stated that the ‘Japanese have white hearts beneath their yellow skin’ (Shimazu 2009:163).

Conclusion

Racial understandings of international relations had deep intellectual roots in late 19th century Japan. Thinkers such as Katō Hiroyuki, Oka Asajirō, Taguchi Ukichi, and Asakawa Kan’ichi were particularly important in this realm as they bridged the public, state, and global in their careers. Situated at the nexus of public discourse, official policy, and global intellectual movements, they constituted a cluster of highly influential intellectuals whose ideas and theories not only contributed to popular understanding of the war, but to official policy and international debate as well. All understood civilization to be a product of racial qualities, and competition to be an inherent part of race relations. The Russo-Japanese war, to them, was an expression of this conflict, but also an opportunity to amend the conventional understanding of the place of the Japanese within the global hierarchy of races as it was understood to exist at the time. Japan’s ability to challenge the Russians, and eventual victory, proved that the Japanese were by no means racially inferior to their foes. To the contrary, it meant that the ‘Yamato’ were in fact a first-rate people – a group with ‘white hearts’, on par with dominant Anglo-Saxons. Some figures went so far as to argue that it wasn’t the Japanese who were ‘yellow’, but the Russians.

The desire to move closer to the white world, with its associations of progress and power, remained powerful drivers in Japan throughout the lead up to, and during, the Second World War. Indeed, John Dower has shown how to many, the conflict itself was a race war, resulting partly from the bitterness of the ongoing refusal of white imperialism to admit an Asian partner on equal terms – a refusal epitomized by Japan’s experience in the League of Nations (Dower 1986). Defeat in the conflict only exacerbated this sense of inequality, and bred a certain fetishization of whiteness that endures till this day. Until the 1990s, for example, Japanese advertisements for makeup overwhelmingly featured white women, and white models continue to dominate Japanese fashion shows. Similarly Japanese wedding brochures often featured interracial couples where one partner was white, but almost never featured foreign partners of darker skin tones. The work of numerous academics, including Sherrick Hughes, has shown how darker-skinned people were subject to essentialization and characterization as emotional, hypersexual, and aggressive, while conversely the white businessman, white academic, and white model remained figures of exaltation and aspiration in Japan. Furthermore, many Japanese manga, for example, featured nominally ‘stateless’ (mukokuseki) characters who looked suspiciously like Europeans.

Race continues to be a controversial subject, particularly with the recent groundswell of activism associated with the Black Lives Matter movement. Understanding the complexities and histories of local responses to such global moments, however, can go a long way towards avoiding precisely the sort of generalization that those with racially retrogressive views seek to impose on the objects of their ire. The deep-seated notion that the Japanese are somehow more closely related – culturally, politically, biologically – to whites continues to find expression in contemporary Japanese society. Ongoing controversies regarding the ‘Japaneseness’ of darker-skinned Japanese public figures such as tennis player Naomi Osaka, or former Miss Japan Priyanka Yoshikawa, are descended from the efforts of the like of Taguchi Yukichi and Katō Hiroyuki to argue for a pure, superior, and whiter than white Japanese race. One can only hope that, just as the Russo-Japanese War was a moment of firsts, the current moment will be one too – the first of a more open and accepting attitude to race, its implications, and its definition.

Bibliography

Asakawa, Kan’ichi. The Russo-Japanese Conflict: Its Causes and Issues. 1979 [1904] (Dallas, TX: Kennikat Press)

Bartlett, R. ‘The Russo-Japanese War in Russian Cultural Consciousness’. Russian Review, vol. 67, no.1, 2008, p.8-33.

Nagayama, Y. Nichiro sensōji no shinbun to dokusha in Taiheiyōgaku kai shi, vol. 96, 2007, p.74-77.

Connelly, Matthew. Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population. 2008 (London: Belknap Press).

Cross, Sherrie. ‘Prestige and Comfort: the development of Social Darwinism in early Meiji Japan, and the role of Edward Sylvester Morse’. Annals of Science, vol. 53, no.4, p.323-344.

Darwin, Charles. The Descent of Man. 1871 (New York: Merrill & Baker).

Davenport, C.B. Heredity in Relation to Eugenics. 1911 (New York: Henry Holt & Company).

Davis, Winston. The Moral and Political Naturalism of Baron Katō Hiroyuki. 1996 (Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies).

Dower, John. War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War. 1986 (New York: Pantheon Books).

Eskildsen, R. ‘Of Civilization and Savages: The Mimetic Imperialism of Japan’s 1874 Expedition to Taiwan’. The American Historical Review, vol. 107, no.2, 2002, p.388-418.

Esthus, R.A. ‘Nicholas II and the Russo-Japanese War’. Russian Review, vol.40, no.4, 1981, p.396-411.

Franklin, Benjamin. “Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, the Peopling of Countries, etc.” in Ormond Seavey (ed.) Benjamin Franklin: Autobiography and Other Writings. New York: Oxford Univ. Press Incorporated, 1993.

Fukuzawa Yukichi. ‘Datsu-A Ron,’ Jiji Shimpō, 16th March 1886.

Galton, Frederick. ‘Eugenics: Its Definition, Scope, and Aims,’ Nature, vol. 70, no.1804, 26th May 1904, p.82.

Iikura, Satoshi. ‘Pataanarisumu no naka no Nihon’, in Nichiro Sensō kenkyūkai (ed.) Nichiro Sensō kenkyū no shinshiten, 2005 (Yokohama: Seibunsha) p.229-242.

Katō, Yōkō. ‘What Caused the Russo-Japanese War – Korea or Manchuria?’. Social Science Japan Journal, vol. 10, no.1, 2007, p.95-103.

Katada, T. Doitsu hōgaku no juyō katei. 2010 (Tokyo: Ochanomizu shobō).

Katō Hiroyuki. ‘Nippon jinshu kairyo no ben.’ Tōkyō gakushi kaigi zasshi, no. 8, vol. 1, 1886.

——— Shinkagaku yori Kansatsu shitaru Nichiro no Unmei, 1904 (Tokyo: Hakubunkan).

——— Yūkitai no san dankai oyobi dai san dankai yūkitai taru kokka in K. Ueda (ed.) Katō Hiroyuki bunsho, 1990 [1912] (Dōhōsha Shuppan, Tokyo) vol. 3, p.516-519.

Kowner, R. and B. Shillony. ‘The Memory and Significance of the Russo-Japanese War from a Centennial Perspective’ in R. Kowner (ed.) Rethinking the Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905. 2007 (Folkestone: Global Oriental), vol. 1, p.1-11.

Nishida, T. (ed.) Kuga Katsunan zenshū. 1990 (Tokyo: Misuzu Shobō) vol. 8-9.

Oka, Asajirō. Shinkaron kōwa in H. Tsukuba (ed.), Oka Asajirō shu. 1974 [1904] (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō) p.1-301.

Paul, D.B. ‘Darwin, social Darwinism, and eugenics’ in J. Hodge & G. Radick (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Darwin. 2009 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press) p.215-237.

Robertson, Jennifer. ‘Blood Talks: Eugenic Modernity and the Creation of New Japanese’. History and Anthropology, vol. 13, no.3, 2002, p.191-216.

Takahashi, Yoshio. Nippon jinshu kairyō ron in Meiji bunka shiryō sōsho. 1961 [1884] (Tokyo: Meiji Bunka Shiryō Sōsho Kankōkai), vol.6, p.19-55.

Shimada, T. ‘Bakunin no Ajia kyōi ron to Nichiro Sensō no kikaron,’ Journal of International Relations and Comparative Culture, vol. 5, no.2, 2007, p.283 – 313.

Shimao, Eikoh. ‘Darwinism in Japan, 1877-1927,’ Annals of Science, vol. 38, no.1, p.93-102.

Shimazu, Naoko. ‘Patriotic and Despondent: Japanese Society at War, 1904-5,’ Russian Review, vol. 67, no.1, 2008, p.34-49.

————— Japanese Society at War. 2009 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Spencer, Herbert. ‘Progress: Its Law and Causes’ in J.D.Y. Peel (ed.) Herbert Spencer on Social Evolution: Selected Writings. 1975 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) p.38-52.

————— Principles of Biology. 1870 (New York: D. Appleton & Company).

Steinberg, J.W. ‘Was the Russo-Japanese War World War Zero?’ Russian Review, vol. 67, no.1, 2008, p.1-7.

Tabata, S. Katō Hiroyuki. 1986 (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan).

Taguchi, C. Taguchi Ukichi. 2000 (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Koubunkan).

Taguchi, Ukichi. Kōka to wa nanzoya. Tokyo keizai zasshi, 16th April 1904.

————— Hakōka ron in Teiken Taguchi Ukichi Zenshū Kankōkai (ed.) Teiken Taguchi Ukichi Zenshū 1928 (Tokyo: Teiken Taguchi Ukichi Zenshū Kankōkai), vol. 2, p.485-500.

————— Jinkō ron in Teiken Taguchi Ukichi Zenshū Kankōkai (ed.) Teiken Taguchi Ukichi Zenshū 1928 (Tokyo: Teiken Taguchi Ukichi Zenshū Kankōkai), vol. 3, p.442-469.

————– Jū kū seiki no taisei oyobi mirai in Teiken Taguchi Ukichi Zenshū Kankōkai (ed.) Teikein Taguchi Ukichi Zenshū 1928 (Tokyo: Teiken Taguchi Ukichi Zenshū Kankōkai), vol. 5, p.456-459.

————– Katō Hiroyuki shisha jinken shinsetsu wo yomu in Teiken Taguchi Ukichi Zenshū Kankōkai (ed.) Teiken Taguchi Ukichi Zenshū 1928 (Tokyo: Teiken Taguchi Ukichi Zenshū Kankōkai), vol. 5, p.156-167.

Toyoda, Y. Nisshin Nichiro Sensō. 2009 (Tokyo: Bungeisha).

Unoura, Hiroshi. ‘Samurai Darwinism: Hiroyuki Katō and the Reception of Darwin’s Theory in Modern Japan from the 1880s to the 1900s’. History and Anthropology, vol.11, no.2-3, 1999, p.235-255.

Van der Oye, David Schimmelpennick. ‘Rewriting the Russo-Japanese War: A Centenary Retrospective,’ Russian Review, vol. 67 , no.1, 2008, p.78-87.

Wagatsuma, H, and T. Yoneyama, Henken no Kōzō: Nihonjin no Jinshukan. 1967 (Tokyo: Nihon Hōsō Shuppan Kaisha).

Westwood, J. Russia against Japan, 1904-05. 1986 (Albany: State University of New York Press).

Wilson, S. ‘The Russo-Japanese War and Japan: Politics, Nationalism and Historical Memory’, in D. Wells & S. Wilson (ed.) The Russo-Japanese War in Cultural Perspective, 1904-05. 1999 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan) p.160-193.

Yamada, A. Sekaishi no naka no Nichiro Sensō. 2009 (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan).

Yomiuri Shinbun Shuzaihan (ed.) Kenshō Nichiro Sensō. 2005 (Tokyo: Chūō Kōron Shinsha)

Yoshida, H. Katō Hiroyuki no kenkyū. 1976 (Tokyo: Ōhara Shinseisha).

Zachmann, Urs Matthias. ‘Guarding the Gates of Our East Asia: Japanese Reactions to the Far East Crisis (1897-98) as a Prelude to the War’, in R. Kowner (ed.) Rethinking the Russo-Japanese War 1904-1905. 2007 (Folkestone: Global Oriental), vol. 1, 13-30.

Notes

Morse was a zoologist and avowed Social Darwinist who spent time in Japan as a oyatoi gaikokujin, or Meiji-era foreign advisor. He was the first professor of zoology at Tokyo Imperial University (now Tokyo University) and conducted extensive work on Japan’s Jomon era past. For an excellent, detailed, work on his time in Japan, see ‘Prestige and Comfort: Prestige and Comfort: The development of Social Darwinism in early Meiji Japan, and the role of Edward Sylvester Morse’, by Sherrie Cross

As with many of their contemporaries, Takahashi and Kato assumed that characteristics were chiefly passed down through the male line – and race was no exception. This in turn tied in to neuroses around the ‘outbreeding’ of Japanese by foreigners after they were permitted to live anywhere in the country in the late 19th century. The intersection of race and gender is a fascinating line of inquiry that I intend to visit in future work.

Keen observers will note the simplicity of Oka’s syntax here – as mentioned, Shinkaron kowa was in its essence a work of popularization, and hence written in remarkably accessible prose.