Abstract: The right to protection from violence should be conferred upon all people regardless of their nationality. However, migrant women in Japan face exceptional risks, including that of domestic violence. This paper focuses on the vulnerability of Nepalese women, most often in Japan as dependents of their husbands, who are engaged as cooks in the ubiquitous Indo-Nepali restaurants. Shut out of the male-dominated support networks within the Nepalese community, they are forced to rely on Japanese state support in a time of crisis. Yet, despite the fact that most of these women are working and paying taxes in Japan, many are unable to effectively access the state support system, leaving them particularly at risk in times of calamity, as we are seeing now with COVID-19. This paper outlines their vulnerability and calls upon the state to recognize that these migrants are not free riders, but residents entitled to equal rights and protection under the law. At a time when we often hear about the national imperative to “Build Back Better” in the post-COVID-19 period, I hope that these vulnerable populations are included in such building.

Key words: COVID-19, vulnerable populations, Migration, Nepalese, Japan, Social Protection, Right to Life, Violence Against Women (VAW)

Introduction

Savitri moved to Japan eight years ago with her son as a ‘dependent’ family member of her husband, who was working for an Indo-Nepali restaurant. She became a victim of her husband’s physical violence after he lost his job due to the COVID-19-induced economic crisis. She and her son escaped from her husband and moved to a small apartment in February 2020. However, her situation deteriorated further when she lost her part-time job as a cleaner, and her high-school aged son lost what meager income he was earning as a waiter at a cafe soon afterwards in March. Now, with no reliable sources of income, and without the language ability to access information about social welfare programs in Japan, Savitri does not know how to survive.

Consulting the Social Welfare Council in her local municipality, she found that she could not get support due to her visa status as a ‘dependent.’ Despite the threat of physical violence her husband poses, she knows that she cannot extend her visa if she chooses divorce. There is no way for her to claim a visa on her own, since she has not completed the required 12 years of education, and also because she can only speak rudimentary Japanese, such as greetings.

Savitri brought her son to Japan with the dream of providing him access to a better future. She now regrets her decision. She has found that his academic performance in Japan is suffering in both Nepali and Japanese, and furthermore, due to schools moving to remote learning, he is excluded because they lack the necessary technology at home. Supplementary classes for migrant children organized by Japanese volunteers are no longer offered under COVID-19 conditions, and his inability to attend school and work means that his Japanese suffers.

A woman’s right to protection from violence applies to all regardless of nationality. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations include eliminating Violence Against Women (VAW) and are supposed to be universally applied, including in Japan (UN Women, 2017). Additionally, the Prevention of Spousal Violence and Protection of Victims Act applies to all foreigners living in Japan (Gender Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office, 2008). However, despite these protections, migrant women in Japan face serious risks on a daily basis, a situation which has been exacerbated by the coronavirus outbreak. There is some support available, but it does not cover everyone. There are self-help groups for migrants that are committed to the goals outlined in the VAW principles, such as KAFIN–Hanno led by a Filipina. However, many of these groups function primarily within migrant communities dominated by women, such as Thais and Filipinas. This is not the case for the Nepalese community in Japan. Nepalese migrant organizations do exist, but these are led by men (Tanaka 2019). Savitri fears retribution and is afraid of being known as a domestic violence survivor among her fellow Nepalese who are connected with her perpetrator husband. Thus, it is difficult for her to gain support from the predominantly male-oriented safety nets that stretch across the Nepalese community, isolating her from her ethnic network. The only option at her disposal is to try to navigate the inadequate safety nets available from the Japanese government.

The story of Savitri is an amalgamation of existing stories, told in this way to protect the privacy of the individuals struggling with these issues. Savitri’s case illustrates some of the multitudes of problems migrants face, brought on not only by personal circumstances, but also by impractical and often unreasonable policies in Japan. At the end of 2018, the Japanese Government revised the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act to open its doors to a wider range of lower-skilled and semi-skilled foreign workers, meanwhile also launching the “Comprehensive Measures for Acceptance and Coexistence of Foreign Nationals” (Ministry of Justice, 2019). Therein, the word imin (migrant) is not used, instead using gaikoku jinzai (foreign human resources). This careful choice of words labels migrants as resources rather than as human beings, and serves to obscure the difficult realities faced by migrant families and dependents like Savitri. As a wife and mother, she never had a chance to learn the Japanese language or other survival strategies necessary for her to live on her own. Now, she is unable to access the few available programs because of this language barrier.

This article examines migrants’ struggles as they navigate the ongoing COVID-19 situation with limited support from the ethic community, and with insufficient support provided under the social protection schemes in Japan even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. I will conclude by pointing out some of the fundamental problems of Japanese citizens’ lack of understanding and appreciation of the ways that migrants contribute to Japan, their rights under the law, and the importance of ensuring their safety and security while they live in this country.

Japan as a destination for Nepalese family migration

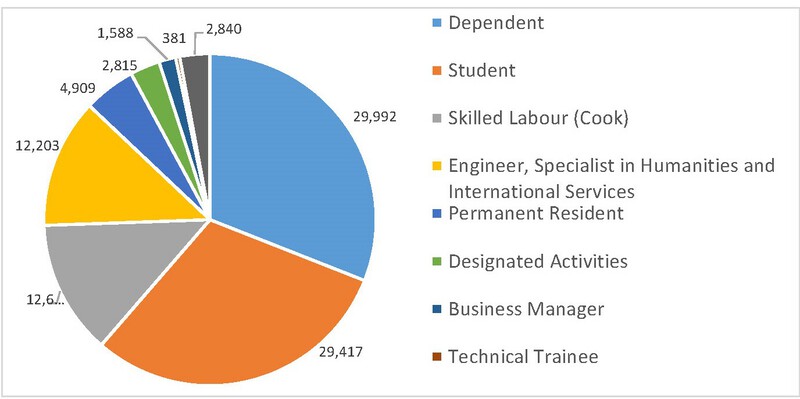

The Nepalese population in Japan has increased more than seven times over a decade, from 12,286 in 2008 to 96,824 by the end of 2019. This increase contrasts with the numbers of Brazilian and Peruvian migrants, whose population has decreased due to the global economic recession in the late 2000s. The number of Nepalese students in Japanese language schools has increased dramatically, while the number of Chinese and Korean students has decreased following the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear power meltdown at Fukushima in 2011. The Nepalese fill the shortages of both laborers and students whose numbers in Japan were once taken by other ethnic groups. Today Nepalese constitute the sixth-largest migrant group in Japan after Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Filipino, and Brazilian migrants. Figure 1 shows the categories of the top legal statuses among them including“dependent” (29,992) followed by “student” (29,417), “skilled labor” (12,679) “engineer, specialist in humanities and international services” (12,203) and “permanent resident (PR)” (4,909).

|

Figure 1: The ratio of registered Nepalese in Japan by residential status at the end of 2019 Source: Ministry of Justice, 2020a. Statistics of foreign residents, Table 1 Foreign residents by nationality, region, and residential status. |

The Indo-Nepali restaurants where most Nepalese migrants work are usually owned by South Asian migrants and attract customers who are of the same nationality. A large number of Nepalese who come to Japan do so with “dependent” status, as family members of cooks with “skilled labor” status. They usually have to pay substantial commissions through local networks in Nepal (Kharel 2016) in order to make it to Japan. Once here, there is an asymmetrical power relationship between the cooks and their employers, who are also often from Nepal. This makes it difficult for the cooks to hold unscrupulous or abusive employers to account. For instance, and what has become especially problematic in the COVID-19 era, many cooks work at restaurants owned by Nepalese who do not have employment insurance (雇用保険 koyō hoken), despite the legal requirement to provide it. However, cooks fear retribution from their employers, who have the power to terminate their contract and even revoke their visa, so they generally do not risk jeopardizing their careers to expose the illegal employment practices they are subjected to.

Although wives and dependent family members made substantial contributions to the Japanese economy, they were also in precarious positions. Wives and dependents are legally allowed to work only after obtaining permission for “non-qualified activities” (資格外活動 shikakugai katsudō), when they are entitled to work up to 28 hours per week. According to statistics from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW), 77.3% of Nepalese workers fall into either the “student” or “dependent” category with permission to engage in “non-qualified activities,” much higher than other visa categories (MHLW, 2020). The students with necessary Japanese language skills fulfill labor shortages in retail shops, bars, and restaurants, and may be able to obtain a stable visa status under “engineer, specialist in humanities and international services” as full-time employees. However, migrants with “dependent” status, mostly women, usually are not eligible because few have learned sufficient Japanese language to acquire a job under this visa. With little opportunity for interaction with Japanese neighbors, the majority never get “mama-tomo” (mum friends) at their children’s schools or nursery classes. As a result, both parents and children are excluded from information about schooling, emergency alerts, and other municipal services. For employment, they are usually engaged in bed-making, cleaning, and laundry services at hotels, or in supply chains making sandwiches and lunch boxes at food processing factories. A few are working at nursing homes as caregivers if they were qualified as nurses in Nepal and were able to gain the required level of Japanese language proficiency.

Household economy and family relations of migrating cooks

As of September 2020, the number of Nepalese cuisine restaurants in Japan is approximately 1,800. This figure has not changed since 2017, according to the restaurant search engine, Tabelog. This indicates that these businesses are no longer flourishing as they were during the early 2010s, mostly due to excessive competition (Tanaka, 2020b). On average, cooks earned only JPY 100,000 per month even before the COVID-19 crisis. Because they cannot change their profession under the legal status of “skilled labor,” their financial situation is difficult. As a result, many wives and children “support” the family by earning part-time wages. The share of women in the total population of Nepalese migrants has been increasing, corresponding to the increase in migrants of “dependent” family status. As of 2019, there were 56,055 (57.9%) Nepalese men and 40,769 (42.1%) Nepalese women in Japan. As shown in Figure 2, more than 10,000 Nepalese children were registered, demonstrating the shift in Nepalese migration toward a more family-unit model.

|

Figure 2: Number of registered Nepalese in Japan by gender and age group as of 2019 Source: Ministry of Justice, 2020b. Statistics of foreign residents, Table 2 Foreign residents by nationality, region, gender, and age. |

Many migrants to Japan pay a substantial initial payment as commission to the restaurant owner or a labor broker, which averages as much as two million yen. This is an exorbitant amount for a single (male) cook, especially from a rural Nepalese village. However, commission and/or brokerage fees are the same even if the whole family migrates, so an increasing number of cooks bring wives and dependent children. Nevertheless, while this family migration strategy mitigates the financial costs, family migration is difficult in terms of the personal dynamics among family members. Full-time cooks often earn a lower wage than their “dependent” family members working part-time. The male cooks might lead migration as heads of the household, but they often face difficulties grappling with the change in power balance among family members when their spouses and children earn more than they do. By the same token, if their children develop a better command of the Japanese language, this can disrupt family relationships as well. Difficult work conditions and discord within the family often contribute to increased rates of alcoholism and domestic violence (Tanaka, 2019).

Dependent children also suffer in this complicated economic and visa-dependent living situation. For example, Kiran entered high school in Tokyo a year after his arrival in Japan. He studied Japanese very hard through a supplementary class and enjoyed student life as a member of a football team. But, as the cook of a small restaurant, his father could not keep up with the educational costs, and in time, Kiran had to start working long hours as a clerk in a retail shop in order to pay for his transportation, schooling, and expenses for the football team. Unable to find the time and space to study at home, he started skipping classes. In the end, despite his friends’ encouragement, he dropped out of school. What he did not realize was that dropping out also disqualified him from gaining his own legal status as “long-term resident” or under “designated activities” because these statuses require a diploma (Ministry of Justice, n.d.). He can still stay in Japan as a “dependent” family member, but he is not allowed to work more than 28 hours per week though he is no longer a working student. He has considered leaving Japan but feels he cannot go back to Nepal without having something to show for his time here. Moving forward, he is unsure of his future and what he will do in Japan.

Difficulty to access Japanese support

In at least partial recognition of some of the difficulties that ethnic minorities face in Japan, government agencies are trying to provide notices in foreign languages, as well as multilingual counseling services operated by Non-Profit Organizations (NPOs). COVID-19 has made many of these difficulties even more challenging and some agencies have tried to respond. For example, while the rate of domestic violence cases increased among Japanese, it has also increased many migrant communities. The Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office launched a “Domestic Violence Hotline Plus (DV +)” operated by an NPO, the Social Inclusion Support Center, in May 2020. It is a 24/7 free counseling service accessible by toll-free call, e-mail, or SNS chat provided in 10 foreign languages: English, Tagalog, Thai, Spanish, Chinese, Korean, Portuguese, Nepali, Vietnamese, and Indonesian, as well as Japanese. It offers consultations as well as on-site interpretation services and information on shelters (Ippan Shadanhōjin Shakai-teki Hōsetsu Sapōtosentā, 2020). Multilingual support opened the door for migrants seeking help locally and nationally, so Nepalese migrants can now get information in Nepali at the labor consultation desk in Tokyo. The increased demand for telework also led to the establishment of telephone interpreting services in other parts of Japan. While this is a step in the right direction, counselors and interpreters report that they feel helpless if their clients cannot use the resources that they recommend.

In principle, there is no discrimination against foreign nationals in access to social protection services (MHLW, 1952; MHLW, n.d.-a). Thanks to the campaign to abolish nationality clauses led by Koreans, Japan’s National Pension and National Health Insurance no longer have barriers to access on the basis of nationality (Kashiwazaki 2013:36). All migrants, with the exception of short-term visitors, pay the same health and pension premium as Japanese citizens. However, not all migrants are entitled to access social protection schemes, including Public Assistance (生活保護 seikatsu hogo), which for many is an essential safety net. Only migrants with permanent resident status, long-term residents, spouses, and family members of Japanese or permanent resident holders can utilize Public Assistance. Migrants with other legal statuses, including “skilled labor,” “engineer, specialist in humanities and international services,” or “dependent,” cannot use it. Similarly, since 2015, municipalities can provide housing security benefits for up to three months as part of the Support Program for Self-reliance of Needy People (生活困窮者自立支援制度 seikatsu konkyū-sha jiritsushien seido) (MHLW, n.d.-d) for migrants, but not for those with student or dependent status.

Sometimes the primary impediment for migrants seeking assistance comes less from the way that the laws are written, and more so in how they are applied. Many local governments and Social Welfare Councils, the front-line offices for social protection, are trying their best to support migrants affected by COVID-19 under existing schemes. However, varying levels of efficacy and consistency are found in different localities. For instance, Nepalese cooks living in Chiba could not get Housing Security Benefits (住居確保給付金 jūkyo kakuho kyūfukin) (MHLW, n.d.-b) while the same scheme granted these benefits to cooks registered in Tokyo in early May. This sort of inconsistency is based on a misunderstanding of welfare laws on the part of local government officials who believe that only “nationals” (国民 kokumin) are entitled to access. In fact, it is a right of all “residents,” including foreign nationals. This misapplication of Japanese law is a reflection of misunderstanding of the human rights of migrants, which leads to the poor delivery of social services to migrants in need. For example, the law allows Municipal Social Welfare Councils to provide an interest-free Welfare Fund Loan (生活福祉資金 seikatsu fukushi shikin) (MHLW, n.d.-c) for migrants in any visa category, including students or dependents, so long as they have at least three months remaining on their visa. However, in fact, only a few migrants are ever granted these loans through local Social Welfare Councils, even after the MHLW issued non-discrimination guidelines (Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan, 2020).

In direct response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Japanese Government announced that all registered persons, including migrants, as of April 27, 2020 could receive a Special Cash Payment (特別定額給付金 tokubetsu teigaku kyūfukin) of JPY 100,000 per person. However, this excludes refugee asylum seekers with residential permits of less than three months and migrants with short-term residential permits who could not extend their legal status due to a lay-off from employment or graduation from school. Some Japanese people raised questions about the decision to give this payment to any migrant, citing as the reason some variation on, “Why should our taxes be used for foreigners?” Ganga Kurihara Dangol, the Chairperson of the Information Dissemination Network for Nepalese Migrants (IDNJ) and counselor of multilingual services, has pointed out that such criticisms are based on a misunderstanding of Japanese law by Japanese citizens. They seem unaware that, in addition to contributing to the Japanese workforce, migrants have been paying premiums for National Health Insurance and the National Pension in addition to various other taxes, just as Japanese citizens do. Kurihara Dangol appealed to Japanese citizens to understand that migrants are not free riders, but are legally entitled to, and pay for, these benefits with the same rights and obligations as Japanese citizens (Tanaka, 2020a).

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis, the Japanese Government has demonstrated somewhat greater flexibility in immigration rules. The Immigration Service Agency announced a special arrangement for trainees (Ministry of Justice, 2020c) and other migrants wherein work permit holders can change their legal status to “designated activities” in order to find other jobs if their original workplaces are affected by COVID-19. Ex-students of Japanese universities or specialty schools (専門学校 senmon gakkō) are also able to extend their status one year if they continue job-hunting in Japan (Immigration Services Agency of Japan, 2020). Cooks with “skilled labor” status can also work for companies in other sectors once they get permission for “non-qualified activities” under this new rule. However, migrants with “dependent” status do not receive benefits under the new rules or schemes, even though some of them had been the main breadwinner in their household.

Japan at a crossroads: Ensuring Migrants’ Right to Life

The revision of the Immigration Law in December 2018 and the newly launched immigration policy, (“Comprehensive Measures for Acceptance and Coexistence of Foreign Nationals”) were implemented without sufficient preparation and understanding on behalf of the Japanese government responsible for their implementation (Menju, 2019). In general, under this poorly framed policy, migrants’ living conditions have continued to be far worse than that of their Japanese peers. Furthermore, those without independent legal status, including those with “dependent” visas, have fewer provisions made for them in social protection schemes, as we have seen in the case of Nepalese migrants. Japanese citizens have gradually come to accept migrants as a necessary source of labor in Japan, but are still not aware of the often severe problems they are subject to, including various forms of vulnerability, such as unemployment, domestic violence, and educational exclusion (Joshi 2020). It is time to create an integrated social protection policy for migrants in Japan that actually supports them and protects their right to life with consistent and sufficient measures. This should be one of the goals of “Build Back Better” in our post-COVID-19 world.

References

Gender Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office. (2008). To victims of spousal violence. Gender Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office.

Immigration Services Agency of Japan. (2020). Shingata koronauirusu kansenshō no kansen kakudai-tō o uketa ryūgakusei e no taiō ni tsuite [About dealing with international students who have been affected by the COVID-19 crisis]. Ministry of Justice, April 6.

Ippan Shadanhōjin Shakai-teki Hōsetsu Sapōtosentā. (2020). Domestic violence hotline plus. Ippan Shadanhōjin Shakai-teki Hōsetsu Sapōtosentā.

Joshi, R. D. P. (2020). COVID-19’s influence on migrant children’s rights in Japan. The International Law Training and Research Hub at the Research Center for Sustainable Peace, May 11.

Kashiwazaki, C. (2013). Incorporating immigrants as foreigners: multicultural politics in Japan. Citizenship Studies, 17(1), 31-47.

Kharel, D. (2016). From Lahures to global cooks: Network migration from the Western Hills of Nepal to Japan. Social Science Japan Journal, 19(2), 173-192.

Menju, T. (2019). Japan’s historic immigration reform: A work in progress. Nippon.com, Feb. 6.

MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare). (1952). Seikatsu ni konkyū suru gaikokujin ni taisuru seikatsu hogo no sochi ni tsuite [About measures of welfare for foreigners who are poor in life]. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, May 8.

MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare). (n.d.-a). Gaikokujin no minasan e (shingata koronauirusu kansenshō ni kansuru jōhō) [To foreigners (information on new coronavirus infection)]. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare). (n.d.-b). Information about the housing security benefit. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare). (n.d.-c). Guidance on temporary loan emergency funds. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare). (n.d.-d). Self-support of needy person. Ministry of Health, Labour & Welfare.

MHLW (Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare). (2020). Gaikokujin koyō jōkyō no todokede jōkyō no matome [Summary of the notification status for employment status of foreigners]. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Jan. 31..

Ministry of Justice. (n.d.). Kōtō gakkō sotsugyō-go ni Nihon de shūrō o kangaete iru gaikokuseki o yūsuru kata e [For foreign nationals who are considering working in Japan after graduating from high school]. Ministry of Justice.

Ministry of Justice. (2019). Comprehensive measures for acceptance and coexistence of foreign nationals. Ministry of Justice.

Ministry of Justice. (2020c). Jisshū ga keizoku kon’nan to natta ginō jisshū-sei-tō ni taisuru koyō iji shien ni tsuite’ [About employment maintenance support for technical intern trainees who have difficulty continuing training immigration control Agency]. Ministry of Justice, April 17.

Ministry of Justice. (2020a). Zairyū gaikokujin tōkei dai ichi hyō kokuseki chiiki betsu zairyū shikaku (zairyū mokuteki) betsu zairyū gaikokujin [Statistics of foreign residents, table 1 foreign residents by nationality, region and residential status.]

Ministry of Justice. (2020b). Zairyū gaikokujin tōkei dai ni hyō kokuseki chiiki betsu nenrei danjo betsu zairyū gaikokujin [Statistics of foreign residents table 2 foreign residents by nationality, region, gender and age].

Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan. (2020). Shingata koronauirusu no kansen kakudai ni tomonai seikatsu ni konkyū suru gaikoku hito e no shien-saku ni tsuite (yōseioyobi Kōrōshō kara no kaitō) [Regarding support measures for foreigners who are in need of living support due to the spread of new coronavirus infection (request and response from Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare)]. Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan, April 20.

Tanaka, M. (2019). Roles of migrant organizations as transnational civil societies in their residential communities: A case study of Nepalese organizations in Japan. Japan Review of Cultural Anthropology, 20(1), 165-206.

Tanaka, M. ed. 2020a. 「日本で暮らす移民の声を聞こう!-新型コロナウイルスがうきぼりにした移民を取り巻く課題と希望」セミナー報告書」 “Nihon-de-kurasu Imin-no-koe-o Kikou – Shingata Korona wirusgaukiborinishita Imin-o-torimaku kadai to kibou, seminar houkokusho” (Report on the seminar, ‘Let us listen to migrants’ voices – Challenges and hopes of migrants’ communities under covid-19 crisis).

Tanaka, M. (2020b).「感染症危機と在日ネパール人:相互扶助の限界と日本の社会資源の利用」 “Kansensho-kiki to zainichi Nepal-jin: Sougofujyo-no-genkai to nihon-no-shakaishigen no riyou” (Nepalese migrants in Japan under the COVID-19 crisis: Limitation of mutual help among migrants’ community and using social protection scheme in Japan), M-Net, 210.

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. (2016). Concluding observations on the combined seventh and eighth periodic reports of Japan. Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women.

UN Women. (2017). Spotlight on sustainable development goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. UN Women, July 5.