Abstract: This is a collection of original articles on diverse vulnerable populations in Japan in the wake of the new coronavirus pandemic. The effects of COVID-19 are felt differently, with some among us at much greater risk of infection due to preexisting health and welfare conditions. For others, perhaps more than the risk of infection, it is the precautions taken to mitigate the risk for the whole population, such as lockdowns and business closures, that have pulled away the already fragile safety net of state and civil society organization (CSO) support, leading to increased marginalization and social exclusion. The goal of this set of papers is to document the conditions of those that have been most directly affected by the virus and to provide background on the conditions that made them vulnerable in the first place, notably chronic conditions that are brought into more obvious relief in light of emergency measures. Each of the authors had a pre-established relationship with those affected populations and employed various ethnographic approaches, some face to face, others digitally via Zoom interviews and SNS exchanges. In this moment of what appears to be relative calm, we hope that our collection, quickly compiled in an attempt to capture the ever-changing situation, will give some insight into how those most vulnerable are faring in this time of crisis and provide information that will allow us to prepare better before the next wave comes our way.

Keywords: COVID-19, vulnerable populations, health and welfare, disability, homeless, refugees, social media, sex workers, irregular workers, foreign labor, small farmers, restaurants, business closures, Indian workers, Vietnamese workers, Nepalese workers, Japanese restaurants, sanitation workers, children, domestic violence.

Introduction

Japan has thus far escaped what could have been a much more severe breakout of COVID-19. As of August 1st, 2020, while most cases and deaths have been concentrated in Tokyo, nationwide there have been fewer than 30,000 cases and under 1,000 deaths from COVID (Japan COVID-19 Coronavirus Tracker). In comparison with many other countries around the world, Japan has escaped thus far with a lower count of serious casualties despite experiencing a dramatic shrinking of GDP (Mitsuru 2020) and loss of jobs (NHK 2020). But no one really knows how to explain these low numbers (Rich & Ueno, 2020). Few say with any certainty that the relatively mild effects have been the result of intentional planning or systematically executed precautions and mitigation efforts by government agencies. Japan seems to have lucked out for reasons we may never fully understand. The political narrative might shift in time from one of “lucked out” to “well-managed,” (especially as mismanagement of the virus continues in much larger countries such as the United States, India and Brazil, for example) but as yet, no one has taken credit for a job well done. While the comparatively low numbers might breed relief, it is worrisome that there remains uncertainty over how this was achieved, and thus cannot take concerted measures to be better prepared looking forward. If public health experts in and out of Japan are to be believed, we may get another chance soon to fully confront the virus in the event of a second or even third wave of cases. The articles in this collection are preliminary efforts to capture a pandemic whose dimensions are changing every day around the world and in Japan.

The pandemic unfolded before us in slow motion, maybe more so in Japan with its later arrival and our almost constant media monitoring. We have all had to watch as the disaster came our way after slicing through other countries. In fact, most of the articles in this collection report that the news from abroad served as important warning signs, sometimes too late, often ignored or wished away, at best bringing about half-baked measures without a coherent and comprehensive response. As the virus washed in and then washed out, most of us were watching in puzzlement. And yet, even with the warnings and subsequent lead time, many of the most vulnerable in society were still left disproportionately exposed to the risk of infection.

While it has often been said that the virus does not discriminate (Korte et al. 2020), that is of course not entirely true. There are different degrees of vulnerability in any society, and even though we know surprisingly little about the patterns of infection on the individual level (who dies, who survives), if we adopt a broader perspective, the effects on different populations and their correlations to different levels of exposure are more predictable. Sometimes, the particular populations that are most vulnerable are well known to be so. So, when we see arguments that the most important pre-existing condition is poverty (Braveman 2020), or that the virus acts as a “magnifier” of already existing inequality (Vertovec 2020), it does not come as a surprise. These patterns are emerging in familiar ways in global comparisons (United Nations 2020), as well as some preliminary studies of in-country inequality that show similar correlations (for example Mukherji 2020 in the US and Sa 2020 in the UK). While we do not have comprehensive macro-level data for Japan (although see Hashimoto Kenji in Tomei 2020), we know a good deal about pre-existing patterns of vulnerability. Most who participate in community support or engage in activism saw this coming, even if they could not completely prepare for it. As one soup kitchen volunteer explained, “the same people always seem to get hurt.” This time, awareness and even anticipation of these negative effects were not limited to those who were personally familiar with these populations. For example, as soon as the we began hearing about “corona” (as it was first called), there was an increase in mass media coverage of the viral danger to the disabled, the homeless, and victims of domestic violence. These populations are featured anyway in news stories on a regular cycle of stories precisely because they are chronically vulnerable. With the arrival of the coronavirus, this cycle shortened, and some of the stories were moved from the “community” page to the news section. As one colleague commented, “We cannot pretend that we did not see this coming.”

Vulnerability is best charted from many perspectives. Thus, even with the most developed set of quantitative research compiled by the Japan Institute of Labor and Training (JILT 2020), this and other macro-level statistical correlations miss some of the mechanisms that link infection to vulnerability. Ethnographic work, such as our collection, can identify indicators of risk and vulnerability more specifically than general correlations of “poverty” or “inequality.” Rather than by statistical metrics, ethnography has the ability to profile those most vulnerable, in part by taking note of their ability (or lack of ability) to cope with exposure in their immediate environment. While this appears to be roughly correlated with indicators associated with social class or inequality (income and occupation, for example), those who cannot practice social distancing, do not have protective equipment, and cannot stay home are at higher risk. We might call those in this circumstance as being in the “first circle” of effect, including the sick, homeless, incarcerated, and institutionalized; those who experience immediate risk of infection, not by choice or chance, but rather simply because it is characteristic of the conditions of their life. These groups are well represented in our collection.

Withdrawal of support

The slow approach of the virus shaped how this pandemic was experienced by everyone. Unlike the earthquakes in Kobe in 1995 or Tohoku in 2011, where there were explicit triggering events, our anticipation of and early efforts to brace for the arrival of the coronavirus cannot be fully separated from our experience of the virus itself. The threat of the virus, and efforts to prepare for and to mitigate its effects, seemed to occur simultaneously. These mitigation efforts revealed a wider range of vulnerability beyond those who risk immediate exposure to infection, a group we might consider being in a “second circle” of effects. Paradoxically, for those in this group, mitigation efforts have been more damaging than the effect of the virus itself. Although these mitigation efforts were ostensibly directed to protect society as a whole, they often ended up marginalizing or even excluding certain populations from the support they needed to survive. As these mitigation efforts often coincided with the withdrawal of governmental and volunteer services (stay at home, social distancing, etc), those most dependent on those services were hurt most. The calculation of sacrifice—subjecting the few for the good of the many—is not a new phenomenon in Japan or anywhere else. But the precautions against infection often tore apart the thin and in most cases already receding state safety nets and compromised the efforts of the heroic few who work in CSOs (civil society organizations): the churches and mosques, helpers, volunteers and the rarely compensated workers who run the soup kitchens, day care centers, shelters, and other support sites.

A first observation relates to the social and economic effects of this pandemic in Japan as a whole, particularly within this second circle. Even with so few cases and deaths in comparative perspective, we have seen a more severe contraction of the economy by July 2020 than we did during the Lehman Shock of 2008 (Jiji 2020). Japan’s labor ministry reports that more than 40,000 people nationwide have lost or will lose their jobs due to the coronavirus outbreak (NewsonJapan 2020). A more serious resurgence will predictably have more drastic effects on everyone, and the consequences for the populations who are usually supported by CSOs will be especially dire. A number of CSO’s supporting these vulnerable populations have greatly scaled back their support, while others have stopped their activities completely. As we see in the collection, for many populations, without this help, what was once an already precarious situation quickly turns into an impossible one. Soup kitchens close and homeless people do not eat for days. Women’s shelters close and women become trapped inside their house with their abuser. This fallout is a testament to the importance of CSO groups in the support of at-risk populations. It also exposes the lack of reliable governmental support and safety nets in place. This collection documents the government’s inability to effectively respond to existing need, even in the face of what could be considered a relatively minor scare regarding coronavirus in Japan. This should be a wake-up call.

Second, unlike in recent disasters in Japan, where collective hardship increased empathy and stimulated feelings of fellowship that brought in waves of new volunteers (Avenell 2013), in this pandemic we have seen the opposite. Despite the uptick in news coverage of the situations of the vulnerable, we saw far fewer volunteers. Instead of images like the tens or hundreds of thousands of young and old rushing to dig rubble or hand out onigiri in Kobe City or Minami-Sanriku, this year saw a very different dynamic. In large part due to fear of infection, many under-staffed and under-funded CSOs cut back their services or closed altogether. While this withdrawal of services hurt the vulnerable populations that they serve most immediately, many of these groups have been so damaged that they, like many smaller businesses, will probably never re-open. More generally, it is probable that the institutional integrity of the civil society sector itself has been damaged by this crisis in ways that will have much longer-term consequences. Even after the threat of the coronavirus has passed there will be many fewer and weaker institutions in place to promote and accommodate volunteers if and when they return to the scene. 1995 is sometimes called “Year One of the Volunteer Age.” I hope that 2020 is not the final year of that age.

Vulnerable Labor

For many who have stable or what is sometimes still called “regular” employment at larger companies, the hardship was staying at home, working remotely, and being isolated from others. While these lifestyle changes were not easy to adjust to, these employees were able to protect themselves and their coworkers from viral exposure. On the company side, while it required rethinking work patterns, these changes allowed many companies to reduce labor costs during this period. It is not only Netflix and Amazon that have made money during the pandemic—many companies saved money through teleworking, so much so that they are planning to incorporate elements of teleworking in their post-COVID business plans (Hayashi, Watanabe & Ogawa 2020; Sugiura 2020). For higher level employees working at larger companies with a secure job, who have enough space and equipment at home to complete their tasks relatively uninterrupted, the money saved on transportation and sheltering at home (not to mention the 100,000 yen given to all residents by the government) often meant that their income actually increased during the pandemic (as mine did.)

While our collection does not cover this population, it has long been noted that teleworking allows employers to take over living spaces and time through invasive surveillance (Jahagirdar & Bankar 2020) while workers are forced to absorb work costs (Shearmur 2020), problems that have been exacerbated during the coronavirus pandemic. While some changes in work patterns may be necessary in the short term, not all workers can sustain this sort of overhead in the long term, and it is difficult not to see this as further erosion on the already diminished stability and security of “regular” workers. (For discussion, see Kawaguchi 2020).

While we have many reports of job loss, it is difficult to draw precise conclusions across different populations about the rising numbers of jobs lost. Many lost jobs simply do not show up in these numbers if they are short term, limited contract or otherwise more informal, a pattern increasingly common in Japan and many other countries. The vulnerabilities of these working populations are periodically the object of reflection, but in the time of COVID-19, the risks to “irregular” workers have become more obvious. We might think of this group as living in the “third circle” of exposure. Beyond these most vulnerable populations who suffered from increased rates of exposure and withdrawal of support, these in the third circle suffered due to conscious choices of employers that reflect the priorities of companies protecting their profit margins over the welfare of their workers. These workers are sometimes called “essential” by the media in Japan and beyond (which throughout this pandemic seems to have designated as essential those workers who produce something the rest of us would feel inconvenienced if we had to do without). As noted above, while we would like to have systematic large-scale data that correlates and disambiguates the different points in an individual’s profile (income, medical status, work history, etc.) with infection and death rates as well as job loss, protection practices, and beyond, even without clear macro-level data, vulnerable populations are not so difficult to identify by the work expectations placed upon them. At the top of this large and heterogeneous group, are the front-line workers, including doctors who are usually regularly and securely employed, although many nurses, and other hospital staff are not. They are thus working at greater levels of risk. Below this group, in terms of social prestige, are those doing some sort of “contact work,” meaning contact with the public, with food (growing, serving or preparation, especially meat), or delivering goods. These workers are often cleaning or working in transit or security. These are workers who usually do not have the option to quit working—if they do not work, they get fired, and if they get fired, they do not get paid. Some of these workers do not have health insurance and few enough savings to last very long without a paycheck. So, they work. They often go without sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE) even in situations where social distancing is not possible (or not profitable for their employer). Thus, many of these workers find themselves doubly vulnerable, once from the immediate threat of infection and then occupationally vulnerable.

In the rhetorical shift from the glorification of postwar “regular workers” to celebration of “freedom and flexibility,” there was the creation of a whole range of contract statuses that for a time obscured insecurity of this group of workers. There were moments when their vulnerability came to light — most clearly in the Lehman Shock of 2008 and its aftermath that turned into a political point of contestation around Haken Mura (tent villages of the homeless) (Shinoda 2009). But in 2020, irregular workers found that their job status entailed not only instability but also exposure to the coronavirus, and in some cases, a threat of loss of governmental benefits and protections that all residents are supposed to have. While the Japanese economy as a whole is increasingly reliant on this sort of flexible labor, these workers are the first to have their hours slashed, their pay reduced, and to be laid off. Within this group, some receive appreciation for their sacrifice—for example front line workers, even as they are asked to work overtime without overtime pay and often without PPE. But many irregular workers, whether due to their race, nationality, social prejudice around the nature of their work, or the fact that they chose this kind of work over more “regular” work, often face questions from society and government regarding their eligibility for protection, compensation, and social respect. Often, their irregular work status allows employers to force them to choose between financial hardship (when they choose not to work to protect their health) and possible infection (when they choose to work despite the health risk). Our collection explores this dilemma amongst sex workers, foreign workers, freelancers, and dependent workers.

We also feature some populations who have managed their risks under COVID-19 by taking greater control of their own immediate situations and have greater autonomy and resources to negotiate and develop strategies of survival. In our collection, these include Japanese restaurateurs (who own their own ventures and have developed good relationships with their communities); independent farmers (who have developed flexibility of product and distribution strategies); and sanitation workers (who have secured safer working conditions through strong unionization). This is not to say that no restaurants will close, no farmers will go out of business, or that no sanitation workers will become sick. Each of these groups are subject to some level of infection and populational risk in this depleted economy. Nevertheless, they have all proven to be more resilient because of strong connections with other workers and consumers, changes in working conditions to prioritize health rather than profit, and the ability to collectively chart a way forward to address the effects of governmental mitigation orders. These cases offer important lessons moving forward, even if such lessons are difficult to apply to society as a whole.

Data and Method

We hope that there will be no need to revive testing regimes or institute contact tracing or to count cases or deaths in the hundreds of thousands. But in part because we managed to escape what others in the world did not, we lack the ability to generate statistically significant data that correlates infection patterns with social class, educational profiles, or even occupational positions. Without these statistical profiles, it probably means that it will remain difficult to determine the social and economic correlations that have emerged in every other hard hit country, where vulnerability is directly linked to poverty, social exclusion, and political powerlessness. Nevertheless, there is no reason to believe that Japan will be exempt from these correlations especially now that watching the widely inconsistent adherence to mask and sheltering requests have disabused us of the myth of Japanese uniformity or compliance with authority. Without large-scale data, it is difficult to imagine governmental effort anticipating, preventing, and mitigating the sort of resurgence that most health experts expect in the near future, that we are already seeing around the world, and, as of August 2020, perhaps in Japan, notably in Tokyo. Reminded that this is a government who announced with great fanfare that it was mailing out two masks per family—not the sort of proactive or imaginative response that instills confidence—we view the future with trepidation.

Ethnographic work contributes a different sort of data that focuses on the person inside the crisis and on the immediate conditions that impact that person. Some of the articles focus on policies that define and often constrain various populations such as the disabled, or dependent Nepalese women. Others focus on the often-failed responses to the pandemic at the institutional level, as in the cases of Indian cooks and Vietnamese technical trainee interns. Each author was asked to include the voices of those at risk in their article. This required different research methodologies. In some cases, such as victims of domestic violence or children in children’s homes, most contact was through support organizations that represent these groups. In fact, where the population in question was most dependent upon external support, the authors’ systematic inclusion of these supporters’ voices tells an important part of the story. Usually, our contact was more direct. Since the authors already had connections based on previous research or support efforts, we were able to call upon that network to provide readers with an understanding of the bigger picture. This enabled researchers to trace the effects of coronavirus on the ground faster than in most cases. No one started from scratch.

The order to social distance and stay at home presented immediate complications in the collection of data (however intrepid the researcher). Some of whom we write about have no health insurance, so direct personal contact with them would put them at great risk. Some researchers did rely on minimal face to face contact, albeit briefly, always in a mask and adhering to social distancing guidelines. Most of us quickly set up and revived personal connections through digital media, often extending the personal check-ins that most of us were already conducting through longer and more focused questions and exchanges. In fact, as Bảo noted, the Vietnamese technical interns were often more articulate and detailed in their texts than in “face to face” Zoom interviews. Different digital approaches sometimes proved to be unexpectedly productive. In particular, articles on freelancers and Kabuki-cho workers showed that the careful scouring of digital bulletin boards and select twitter feeds were effective research strategies due to the centrality of these sites for target populations. These sites have been unusually active during the crisis, as many people were out of work and had extra time on their hands. As such, it was possible to see the effects of the crisis on these populations unfolding in real time online as people voiced worries and dissatisfaction digitally. In this way, digital methods became less a way to compensate for the impossibility of face to face ethnography, and more so an adaptive research strategy productive of unexpected insight.

For most of us, the mass media provided important insights into the health situations and proved to be a useful way to chart public opinion. Authors were asked to reference these articles as much as possible to enable readers to check the unfolding of the crisis. Where there were English language versions of some Japanese news articles, we have made an effort to reference those as well.

Contributors to this collection are of diverse nationality and background Some are more of an activist bent, others academic. Our disciplines also vary—a testament to the value of ethnography. Our authors range from established senior scholars to graduate students and one undergraduate. All of the authors are connected to Sophia University in one way or another, as students or faculty, current or past. I am fortunate to take part in a network with so many talented scholars, who are also actively engaged in society and working to bring these two pursuits together.

I’d like to thank the Sophia University Institute of Comparative Culture for its support of this project.

Outline of papers

The Politics of Etiology

In our attempt to calculate risk of infection, we search for causes and individual vulnerabilities that are then generalized into characteristics of subpopulations or whole populations. We call these comorbidities – for example respiratory illness, diabetes, and hypertension in the case of COVID-19 (CDC 2020). These are often treated as given health conditions that are invoked as variables to explain subsequent infection rates and patterns. And while the comorbidities of COVID-19 are very real, vulnerability is, as always, as much a social and political issue as it is biomedical. That is to say there is a history to this biological condition which developed over time and has led a particular population to be vulnerable in particular ways. The virus is opportunistic, and even though the infection patterns are not yet widely understood, it seems impossible to make any sense of its path apart from these environmental conditions. As such, vulnerability is a social fact in and of itself — something that needs to be explained, unpacked, and situated historically, socially, and politically. Each of our authors worked to explain the social facts and to interrogate the conditions that led these populations to be in their respective situations.

For example, in the first circle of exposure, while Bookman notes that many disabled people have a higher risk of infection, his article examines the social context and political struggle that surrounds issues of institutionalization and the transformation of the urban environment. As someone who is a disabled person himself, he sees clearly how, for example, the lack of accessible ramps and elevators has worked against disabled people seeking key resources during this coronavirus crisis. He also shows how these problems are not only the result of crisis reaction but are equally a function of a longer history of funding and policy formation within different levels of government. Even as the disabled and caregivers express anxiety over the future, in situating COVID within this context of institutionalization in Japan, Bookman is able to highlight the role of disability activists fighting to improve the situation.

Figure 1: Author illustrating the difficulty of Tokyo navigation

Tokyo’s homeless population is overwhelmingly older and male, many with respiratory impairment, all of which put them at high risk of serious infection. But as Ikebe and Slater point out, these features are directly linked to a pattern of neglect, especially regarding the lack of health insurance and medical care. When you have no home, you cannot shelter in place, and living on the street makes it impossible to create the sort of protective barriers that the governor of Tokyo has called for. In a more systemic way, the reduction of welfare payments and the withdrawal of social services for the homeless (and many others most in need of the state support) increase their risk and place an impossible burden on the shoulders of a few NPOs who support them. Based on current ethnography and previous interview research, this article captures the street survival strategies and some support groups’ efforts to help these people.

Figure 2: Four of the many asylum seekers without health insurance in Tokyo

If the virus enters the Shinagawa Detention Center, or indeed any closed institution, it is impossible to protect those inside. The generally poor health of the refugee asylum seekers is a well-documented medical fact, one that is directly traceable to poor diet, lack of movement, and uneven distribution of medicine within the detention centers. It is also impossible to overlook the immediate danger of the lack of freely circulating air through the crowded conditions of the detention center. It is for this reason that not only refugee detention centers, but even jails around the world have been releasing those trapped inside. As Barbaran and Slater show through interviews of detained and released refugee applicants, the underlying problem is the lack of a coherent immigration and refugee policy, and the overuse of detention centers as a punitive measure against those who apply for asylum in Japan. Because Japan’s refugee recognition rate is notoriously low—fewer than 1% of applications for refugee status are accepted—thousands of refugees have been forced to choose between detention and returning to the home-country persecution they fled from in the first place.

Figure 3: A lesson at one of the Children’s Homes

Institutionalization, even when not punitive in intent, can be dangerous. This is especially true when people are working under social distancing or stay-at-home orders. As noted above, all institutionalized populations are at risk in times of pandemic, so much so that in some contexts, a decision is made to completely seal off that population. Rossitto documents the struggle inside what are sometimes called “Children’s Homes,” institutions for children whose families are alive but cannot take care of them due to poverty, domestic violence, or divorce. These are non-profit institutions licensed by the state that depend heavily on volunteer and low-paid staff to create a functional and supportive environment. Over the past few months, fear of infection has led to a near-complete lock down of these facilities, prohibiting access not only by parents (who are often still involved with their child’s life), but also outside staff who support the educational and social needs of the children. This article addresses both the institutional challenges the homes face during these uncertain times, and the day to day challenges they face in supporting this vulnerable population.

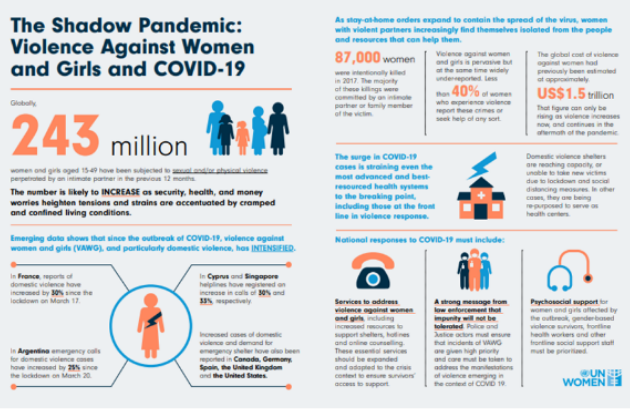

Figure 4: United Nations infographics on DV during COVID-19

While we are all told to stay home for our own protection, for victims of domestic violence (DV), home is the most dangerous place to be. In a situation so bad that the UN has coined the term “shadow pandemic,” Ando explains the continual fear and ever-present danger to (mostly) women living with perpetrators who have lost a job, are anxious over money and the future, and are staying home. Nakajima Sachi, one of the leaders in the movement to support victims of DV, worked with Ando to document the perpetual stigma surrounding DV and its survivors that has been compounded by the withdrawal of already meager support under COVID-19, such as DV hotlines and the few shelters. Ando juxtaposes women’s voices and Japanese legal policies from family registers to domestic violence laws that expose women and privilege men, even confirmed perpetrators of domestic violence.

|

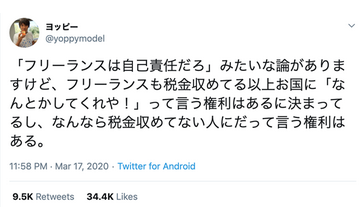

Figure 5: “Theories are hanging about saying that ‘Freelancers are responsible for themselves’ but freelancers also pay taxes, and have the right to say, ‘Do something about it..'” (Twitter, @yoppymodel, March 17, 2020) |

Entrepreneurial Work During the Pandemic

The increase in irregular work (hiseki sha-in), including part-time, contract, subcontract, and freelance, has become an increasingly important part of Japan’s neoliberal economy. As Uno and O’Day point out, the Abe administration promotes this sort of work as a path to “personal freedom,” although the coronavirus disaster has resulted in many being laid off, often without compensation from their employers, forced to search for whatever work is available. When governmental support also appeared to be threatened, tech-savvy freelancers organized an online protest and petition. The mass unemployment put into perspective the relationship between their ambiguous status in a changing market economy and their political status as citizens. Through a thorough search of online sites that have become increasingly important as the main (and often only) connection among these irregular workers, the authors assembled digital posts which revealed their struggle for economic survival, social recognition, and political rights.

While freelancing may be a relatively new work category in Japan, those involved in sex work have long been engaged in freelancing. Freelancers and sex workers share a marginal and unstable position despite their importance in the economy. Giammaria points out that in addition to this instability, the hosts and hostesses of Kabuchi-cho often suffer from social prejudice — prejudice that is experienced by sex workers around the world, but also draws on much older imagery of pleasure quarters in Japan. Without job security, while doing what many call “essential” labor, their safety deteriorates quickly, as the intimate nature of their work puts them at unusually high risk. Suffering media accusations that their work is the source of Tokyo’s recent large outbreak of infections even led to a call for fo the state to withhold their 100,000 yen compensation payment. Like the article by Uno and O’Day, this article brings together the many voices of workers as they talk (text) of their struggles to stay afloat in the face of ever-changing popular opinions while living outside of the main flows of work and social respectability.

Figure 6: Vietnamese Technical Trainee Intern protesting outside of the Vietnamese Embassy in Tokyo. His sign says, “Please help us go back.” |

Foreigners Laboring Under COVID-19

Foreigners facing restrictive visa regulations often struggle to make ends meet while being exploited by their employers. They do not have the resources to address this exploitation and are often unable to access the support systems to which they are legally entitled. Even when the epidemiological threat is less than that facing other groups covered in this collection, the virus continues to act in these situations as a “magnifier” of pre-existing vulnerabilities which compromise protection, information, and support. Vietnamese technical trainee interns, covered by Bảo, are in Japan on a government program, ostensibly as part of a skill-transfer from Japan to “less developed” countries (the Technical Intern Training Program), but by most accounts it functions primarily to bring low-cost labor to struggling businesses in rural Japan. Their work is necessary and valuable, even if most Japanese workers do not choose to do it themselves. Many interns who were lucky enough to keep their jobs during the pandemic have been expected to work with little or no protective equipment. If the firms contracting their labor through these programs lose business, these workers have their hours cut to the point where they can no longer afford to pay rent. Despite being initially eager to bring these workers over to cover labor shortages, after the coronavirus hit, neither the contracting employers nor the overseeing government agencies have been willing to take responsibility for them when their labor became unnecessary, risky or costly, leaving them stranded and without assistance.

Wadhwa’s article discusses the difficult position Indian restaurants across Japan experience. While the owners’ problems are shared by those of their Japanese restaurateur counterparts—struggling to cover rent in the face of a dwindling clientele—their situation was made worse when they were asked to close under the state of emergency directives. The Indian cooks brought over by the owners are particularly vulnerable. With no work, no ability to change jobs due to visa restrictions, and social isolation, they are trapped. Like the Vietnamese interns, the Indian cooks are usually only paid while they work. Because of their visa status, they are not covered by Japanese labor and welfare laws. Most have come to Japan with the intent to send money back to their families in India. Instead they are not working, most are eating through their savings and are afraid to go outside for fear of infection. Through the voices of both owners and cooks, Wadhwa reveals different experiences within a single ethnic community, and even a single enterprise that has been torn apart by the virus.

Figure 7: Indian Cook in the kitchen

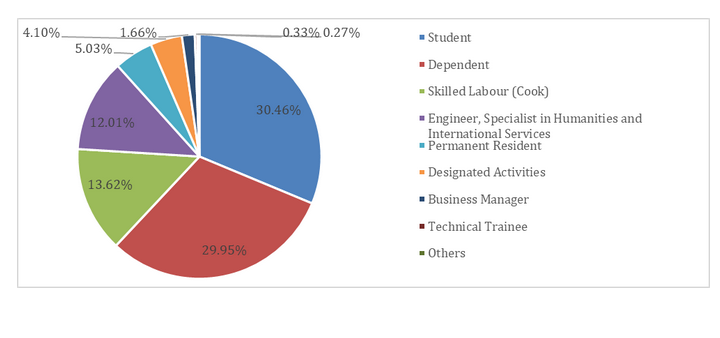

The dependents—wives and children—of Nepalese workers (most of whom are also cooks) in Tanaka’s article lack even the minimal protections that their visa holder husbands can claim. Members of a new wave of migrants, the Nepalese have become the 6th largest migrant group in Japan. Based on years of work within this community, Tanaka documents the struggles of migrant women who have been forced to flee their homes, in this case due to domestic violence brought on by the extreme conditions of COVID-19 life. Like Japanese victims of domestic violence in Ando’s article, these women must fight social stigma within the Nepalese community, but they also are forced to access a Japanese public welfare system where they face racial prejudice that often excludes them from support services that they are legally entitled to. These obstacles are common experiences for the increasing number of migrant workers and family members who have moved to Japan; women are even more vulnerable. This article shows how even a slight disruption can create an impossible situation with great danger for those affected.

Figure 8: Distribution of visa types of Nepalese in Japan

Resilience Through Controlling their Environment

Some of our articles provide a more positive outlook. Each of these cases show that by working together, the immediate viral risks can be managed and new practices can mitigate the negative effects of the lifestyle changes forced upon them due to the coronavirus. The Japanese restaurant owners Farrer writes about, while financially challenged, usually manage their own spaces, the flow of people within those spaces, and their own resources. They can serve food indoors, offer take-out, or choose to close temporarily. In their case, ownership entails control and grants the opportunity to shelter in place (stay home completely), or if going out, to keep a safe social distance. Farrer outlines the many difficult financial choices that these entrepreneurs have to make, but as someone with years of involvement with the local food cultures of Tokyo, he also points to what he calls “community-based resilience” — the networks of trust and support that have developed over time both within an enterprise and with their customer base. These factors allow many restaurateurs to manage immunological risk and the anxiety associated with it, leading to adaptive and sustainable plans for moving forward, at least so far.

Figure 9: The author taking out dinner at his local restaurant

At the other end of the supply chain are the small, independent farmers studied by Kondo and Lichten. These farmers have fared better than many during this time of crisis, despite the threat to sales. In response to living through the dangers of radiation in 2011, as well as more generally in dealing with the risks that are always part of farming, many had already moved away from a single product flow to diversify their product lines and expand their networks. When farmers began to feel the effects of COVID-19, many were able to identify new customers and develop new distribution methods, including online sales. Due to strong community ties with other farmers and their customer bases, they were able to ensure food security and enough product flow to stay afloat. These farmers teach the importance of flexibility, rather than simply size, as the key to resilience.

Figure 10: An promotion by local farmers to promote sales

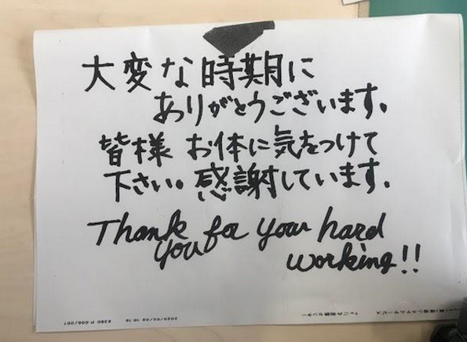

Both of the populations share important traits with the city sanitation workers that Deguchi and Matsumoto describe. Being front-line “essential” workers picking up unsecured consumer trash carries great risk of infection, but as city employees they have a strong union that is responsive to their needs and has been able to, for example, secure them PPE (personal protective equipment). Even though they suffer from the age-old stigma for doing “unclean work,” their union has helped to strengthen the connection between them and the communities they serve. During the COVID-19 crisis, sanitation workers reported increased levels of appreciation shown by their communities for their sacrifice and commitment. However, the authors caution that waste management is being sold off to private companies who hire non-union workers who lack the protections that ensure safe working conditions and job security. This bodes ill for sanitation workers in any future pandemic.

Figure 11: A thank you letter to the sanitation workers for their hard work

Readier for the next time? Building back better?

Based on these preliminary studies, it is difficult to identify any bases for effective responses coming from government in the event of a future pandemic. Government support systems are often difficult to access, and when secured, are usually inadequate to address the problem, particularly for marginal populations. Civil Society Organizations, when called upon to do more than provide compensation, have generally proved inadequate to respond to the rather mild coronavirus effects thus far experienced in Japan. While some scholars have called for a substantial expansion in government benefits to keep more people from falling into the underclass (Tomei 2020), there is little evidence that this is part of the Abe administration’s agenda. If this was a practice run — a dress rehearsal so to speak — large swathes of Japan have reason to worry.

All of our articles address groups that were vulnerable to begin with, and who have suffered disproportionately, even as some far better than others. Of course, we examined only a sample of sectors affected by the pandemic. There is much research to be done. Outside of Japan, most studies have focused on more elite company workers, many teleworking from home, and on mental health. (It would appear that this is, at least in part, because much of this work can be done online.) Our collection is, of course, incomplete. Given the opportunity, we need to hear voices from small factories and police forces, construction workers and convenience store and fast food franchise employees. We need to hear from those in delivery work, where profits and increased hiring have occurred despite the lack of safety measures which have led to lawsuits in the United States against companies like Uber Eats and Amazon (Reuters 2020). There are many more groups to cover, and we are certainly not yet able to gauge all the effects this virus will have on Japan and the world. We hope that our collection will stimulate other researchers to pursue the stories and experiences of other vulnerable populations before the next wave of coronavirus strikes.

References

Avenell, S., 2013. The Evolution of Disaster Volunteering in Japan: From Kobe to Tohoku. In Natural Disaster and Reconstruction in Asian Economies (pp. 35-50). Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Braveman, Paula. 2020. “COVID-19: Inequality is Our Pre-Existing Condition,” UNESCO Inclusive Policy Lab, 14 April.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) – People with Certain Medical Conditions, 17 July.

Jahagirdar, R. and Bankar, S., 2020. EMPLOYEES PERCEPTION OF WORKPLACE MONITORING AND SURVEILLANCE. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 6(1).

Hayashi, Eiki; Watanabe, Kana & Ogawa, Manami. 2020. “Stop logging hours: Japan finds flexibility in age of telework,” Nikkei Asian Review, 16 May.

Japan COVID-19 Coronavirus Tracker.

Japan Institute of Labor and Training. 2020.『新型コロナが雇用・就業・失業に与える影響』 (new coronavirus infectious diseases Impact of new corona on employment, employment and unemployment), 31 July.

Jiji Press. 2020. Japan Estimates FY 2020 GDP Growth at Minus 4.5 Pct. 30 July.

Kawaguchi, Minoru. 2020. 『コロナで「オンライン階級」が生まれた 東浩紀と藤田孝典が斬る「社会の歪み」』(In Corona, “Online classes” were born — “Social distortion” cut by Azuma Hironori and Fujita Takanori), Goo News, 23 May.

Korte, K.J., Denckla, C.A., Ametaj, A.A. & Koenen, K.C. 2020. “Stigma: Viruses Don’t Discriminate and Neither Should We!” Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University.

NHK World. 2020. “32,000 workers in Japan fired amid pandemic,” NHK World – Japan, 17 July.

Mitsuru, Obe. 2020. “Japan GSP to shrink 4.7% in fiscal 2020, BOJ says,” Nikkei Asian Review, 15 July.

Mukherji, Nivedita. 2020. The Social and Economic Factors Underlying the Incidence of COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in US Counties. MedRxiv. 14 July.

NewonJapan. 2020. Coronavirus Blamed for over 40,000 Job Losses. 30 July.

Reeves, Richard V. & Rothwell, Jonathan. 2020. “Class and COVID: How the less affluent face double risks,” Brookings, 27 March.

Reuters. 2020. “Amazon to Hire 100,000 New Workers as Online Orders Surge on Coronavirus Worries,” The Japan Times, 17 March.

Rich, Motoko & Ueno, Hisako. 2020. “Japan’s Virus Success Has Puzzled the World. Is Its Luck Running Out?” The New York Times, 26 March.

Sá Filipa. 2020. Socioeconomic Determinants of Covid-19 Infections and Mortality: Evidence from England and Wales. VOCeu/CEPR. 08 June.

Shearmur, Richard. 2020. Remote Work: Employers are Taking over our Living Spaces and Passing on Costs. The Conversation. 19 June.

Shinoda, Toru. 2020. Which Side Are You On? Hakenmura and the Working Poor as a Tipping Point in Japanese Labor Politics. The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 14-3-09, April 4.

Sugiura, Eri. 2020. “Coronavirus Measures Promise Relief for Japan’s Labor Crunch,” Nikkei Asian Review, 12 May.

Tomei, Toshio. 2020. 『日本人は「格差拡大」の深刻さをわかっていない』(Japanese do not understand the seriousness of the ‘widening gap’), au One – Economy/IT, 30 June.

Vertovec, Steven. 2020. “Covid-19 and Enduring Stigma,” Max-Planck-Gessellschaft, 27 April.

United Nations. 2020. COVID-19 Pandemic Exposes Global ‘Frailties and Inequalities.’