Abstract

This excerpt from the author’s recent book Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo (Harvard University Press, 2018) describes the dramatic climax of the massive 1960 protests in Japan against the US-Japan Security Treaty (abbreviated Anpo in Japanese), which is the treaty that continues to allow the United States to station troops on Japanese soil to this day. Events described include the May 19th incident, in which Japanese prime minister Kishi Nobusuke shocked the nation by ramming the treaty through the National Diet after having opposition lawmakers physically removed by police; the Hagerty Incident of June 10, in which a car carrying US envoys was mobbed by protesters, necessitating a dramatic rescue by a US Marines helicopter; and the June 15 incident, in which radical student activists forced their way into the National Diet compound, precipitating a bloody battle with police during which a young female university student was killed. Shock at these events accelerated a variety of transformations in US-Japan relations and Japanese politics, society, and culture that continue to shape contemporary Japan and which are described in detail in the book excerpted here.

Keywords: Anpo, US-Japan Security Treaty, Kishi Nobusuke, Hagerty Incident, Kanba Michiko

Sixty years ago this month, in June 1960, the largest and longest popular protests in Japan’s modern history reached a stunning climax. At issue was an attempt by Japan’s US-backed conservative government to pass a revised version of the US-Japan Security Treaty – the pact, abbreviated as Anpo in Japanese, which continues to allow the United States to maintain military bases and troops on Japanese soil to this day. The 1960 treaty was a significant improvement over the original treaty, which had been imposed on Japan by the United States as a condition for ending the US military occupation of Japan in 1952. For example, it added an explicit commitment that US troops stationed in Japan would defend Japan if Japan were attacked, and deleted an odious provision in the original treaty allowing US troops to be used to put down internal demonstrations in Japan. However, many on the left in Japan, and even many conservatives, chafed under the neocolonial domination of the United States and hoped to get rid of the Security Treaty entirely, in order to chart a more independent course for Japan within the Cold War international system. In order to show their dismay with any treaty whatsoever, these anti-treaty forces—which included leftist political parties, labor unions, student organizations, a variety of civic groups, and even some conservative business associations—sought to block passage of the revised treaty entirely, even though the new treaty was demonstrably better than the old one.

The anti-treaty movement began in the spring of 1959, while the final details of the new treaty were still being negotiated, and gradually ramped up over the course of 1959 and into 1960. Meanwhile, the opposition Japan Socialist Party used all manner of delaying tactics to try to stall passage of the treaty in the Japanese National Diet. By the time the protests climaxed in June 1960, an estimated 30 million people—about one-third of Japan’s population at the time—participated in some manner in cities, villages, and towns all across the nation. Although the 1960 Anpo protests ultimately failed to prevent passage of the treaty, which remains in effect to this day, they did succeed in bringing down reviled prime minister Kishi Nobusuke (the grandfather of Japan’s present prime minister Abe Shinzō), as well as preventing a planned visit to Japan by US president Dwight D. Eisenhower. The ambiguous outcome of these protests, and the revolutionary and counter-revolutionary reactions they engendered, hold many resonances with later protest movements such as the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests in China and recent protest movements in Hong Kong and the United States.

My recent book Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo (Harvard University Press, 2018) , charts the wide-ranging impact of these massive protests on US-Japan relations, Japanese domestic politics, and Japanese society, literature, and the arts. The following excerpt, from the book’s introduction, describes the dramatic climax of the protests in June 1960.

By the end of April 1960, the Japanese left had essentially been fully mobilized. The successful overthrow of dictatorial leaders that month in two other US Cold War satellite states, Turkey and especially neighboring South Korea, proved that unpopular regimes could be felled by peaceful mass movements, further fueling the protests in Japan, and the April 26 united action saw a significant increase in the size of the protests. Then on May 1, an American U-2 spy plane piloted by Francis Gary Powers was shot down over the USSR. The resultant furor led to the dissipation of the amiable “spirit of Camp David” that had prevailed between the United States and the USSR since the meeting between Eisenhower and Nikita Khrushchev the previous September, and ultimately resulted in the cancellation of the Paris Summit and Eisenhower’s planned trip to Moscow. It came to light that several U-2 spy planes were based in Japan, and with tensions rising between the free world and communist camps, it seemed a particularly inopportune time to be entering into a military alliance with one of the two sides, let alone hosting a visit by Eisenhower himself.

Meanwhile Prime Minister Kishi began quietly laying plans of his own. Having been repeatedly rebuffed in his efforts to bring the treaty to a vote on the floor of the Diet, in no small part because of the uncooperative stance taken by disgruntled factions within his own party, Kishi decided that more desperate measures would be needed. On April 14, he established a top-secret “Anpo Ratification Special Measures Committee” (Anpo Shōnin Tokubetsu Taisaku Iinkai) within his own faction, rather aptly nicknamed the “Anpo Kamikaze Squad” (Anpo Tokkōtai), to map out a strategy for forcing the treaty through the Diet at any cost. Although debate continued for more than a month, from this point onward Kishi had clearly already given up on the debate and was committed to taking “special measures” to ram the treaty through before the end of the current session.1

With the Diet session scheduled to end on May 26 and Eisenhower scheduled to arrive in Japan on June 19 for a visit commemorating the one hundredth anniversary of US-Japan friendship (1960 being the one hundredth anniversary of the first Japanese embassy to America), Kishi put his plans into action on May 19, 1960, exactly one month before Eisenhower was scheduled to arrive. That morning, in a sudden “sneak attack” that the leftist intellectual Hidaka Rokurō would later compare without irony to the devastating Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the LDP suddenly moved to extend the Diet session for fifty days.2

In response, Socialist Diet members and their burly, recently hired “secretaries” launched a sit-in in the hallways to prevent Speaker of the Lower House Kiyose Ichirō from reaching the rostrum to call for a vote. Barricaded in his office for several hours, Kiyose repeatedly appealed to the Socialists over the Diet building loudspeaker system to cease their disorderly behavior. At 11:00 p.m., Kiyose took the drastic measure of summoning 500 police officers into the Diet building. In front of the eyes of a stunned nation watching a live feed on NHK television, the police physically removed each struggling Socialist Diet member from the building, one by one. It was only the second time police had ever entered the Diet chambers, and the first and only time they ever physically removed Diet members.3

Finally, at 11:48 p.m. Kiyose, with the assistance of the police, was able to battle his way through the melee to the lower house rostrum and gavel for a vote, upon which the Diet session extension was immediately passed by those LDP members present. It was then that the second part of Kishi’s “sneak attack” was put into action. At midnight on May 20, just minutes after the extension was approved, Kiyose gaveled the new Diet session into order and immediately called for a vote on the treaty itself. In a famous and indelible image, the NHK television camera captured the LDP Diet members raising their hands to vote their approval, and then swung dramatically to the right to show that all the seats in the other half of the chamber, where the opposition parties normally sat, were empty.

Everyone had been expecting Kishi to try to extend the Diet session, but few people, even within his own party, had realized that he was also planning to ratify the treaty at the same time. This was a crafty maneuver because under Diet rules at the time, any treaty passed by the lower house would automatically be approved after thirty days, even without action by the upper house, as long as the Diet remained in session during that time. By passing the treaty through the lower house on May 20, Kishi ensured that the treaty would automatically be ratified at midnight on June 19, just in time for Eisenhower’s arrival in Japan later that day.

This so-called May 19 incident sparked an intense nationwide uproar, as many people who had previously had no interest in the treaty issue or even favored treaty revision felt deep outrage at Kishi’s “undemocratic” actions. Immense street protests became almost a daily occurrence in Japanese cities, and the movement quickly swelled to include a variety of unaffiliated actors and spontaneous actions. Support for the protests was running so high that the Sōhyō labor federation was able to organize three massive, nationwide general strikes of unprecedented size on June 4, 15, and 22.

A defining characteristic of the protests after May 19 was that they had become less of an anti-treaty movement and more of an anti-Kishi movement. Kishi was physically unattractive and had never been particularly popular with the masses. Moreover, his choice of tactics on May 19 served as a vivid reminder of aspects of his past that nobody had entirely forgotten—namely, that he had served as vice minister of munitions in the Tōjō Hideki cabinet at the height of the Pacific War, and after defeat had been imprisoned by the US Occupation as a suspected class-A war criminal in the infamous Sugamo Prison in Tokyo pending trial before being depurged as part of the “Reverse Course.”

It was a tribute to Kishi’s genius for backroom politics that he was able to overcome such a damning personal history to rise as high as the premiership less than a decade after being released from prison. However, as brilliant as he was at backroom wheeling and dealing, he was almost equally unbrilliant at forging connections with the average citizen, especially in an increasingly televised age. When his personal history was placed in context with his determined efforts to break the leftist Japan Teachers Union (Nikkyōsō) and revise Article 9 of the constitution, along with his mishandling of the 1958 Police Duties Bill, it was a relatively easy sell for his opponents to paint the treaty revision as part of an insidious master plan by Kishi to remilitarize Japan and return to the prewar system.4

Among his other flaws, Kishi had never been particularly adept at maintaining friendly relations with the Japanese press, and after the May 19 uproar the media smelled blood and turned on him with a vengeance, with even conservative newspapers calling for his immediate resignation and the dissolution of the Diet. Meanwhile, the Japanese business world (zaikai), increasingly concerned about the disruptive effect the ever-larger protests might ultimately have on business and Japan’s international trade, began to put intense back-channel pressure on Kishi to resign as soon as possible.

By this point the anti-treaty/anti-Kishi movement had gathered such support and momentum that even ordinary citizens, with no affiliation to any particular organization, began joining the protests. Much was made in the media of white-collar workers leaning out of their office windows to call out their support to the protesters, and housewives joining in marches with their baby carriages. It was at this stage that the capacity of the new medium of television to bring the protest movement into the living room played its most significant role. By June, newspaper reports described how schoolchildren had begun playing “demonstration,” marching around the schoolyard shouting the ubiquitous chant Anpo hantai! (Down with Anpo!).5 With massive protests occurring almost daily, a Yomiuri Shinbun editorial punned that in Japan, “democracy” (demokurashii) had come to mean “living by demonstration” (demo-kurashi).6

After May 19, some protestors seized on the fact that Eisenhower was scheduled to arrive on the day the treaty would be automatically ratified, and sought to direct the protests toward preventing Eisenhower’s visit. Thus when Eisenhower’s press secretary, James Hagerty, arrived at Haneda Airport on June 10, the car carrying him, Ambassador Douglas MacArthur II (the nephew of the general), and an aide encountered a crowd of more than 6,000 protesters blocking their way just outside the airport gates. In what became known as the “Hagerty incident,” the protesters rained blows on the car with their placards and flagpoles, rocked it back and forth, cracked its windows, and smashed its tail lights. Leaders climbed on the roof and led the crowd in chants of “Hagerty, go home!” (Hagachii gō hōmu) and “Don’t come Ike!” (donto kamu Aiku) until the car roof began to cave in. Riot police were called in to try to clear a path for the car to escape, but were resisted with a fierce round of rock throwing. Finally, after more than an hour, the three men managed to escape via a US Marines helicopter.7

Although a suggestion by Socialist Party chairman Asanuma Inejirō that MacArthur and Hagerty had deliberately driven into the crowd as a provocation was widely ridiculed by the Japanese press, a declassified embassy dispatch from MacArthur to the Department of State later revealed this to have been true.8 In any case, the Hagerty incident, particularly insofar as it represented a grave discourtesy to guests of the Japanese nation, came as a profound shock and represented a turning point after which public opinion, especially as reflected in editorials in the mainstream press, first began to turn against the protest movement.

A second, even larger shock resulted from the bloody clashes at the Diet on June 15. That day Sōhyō organized its second nationwide general strike, involving 6.4 million workers, with an estimated 30,000 shops closing down for the day in sympathy, 8,000 in Tokyo alone. As usual, a massive daylong protest was held in front of the National Diet Building. But this protest would be different from those that had come before.

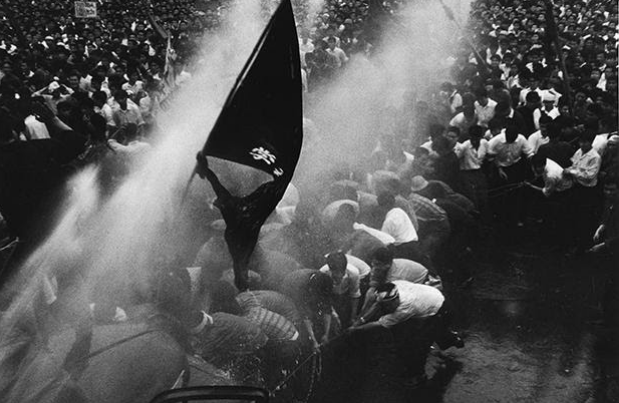

In a fateful moment on June 15, students stormed the south gate of the Diet (parliament) building, eventually forcing their way in. Here they are met with police water cannon.

Around midafternoon, a column of approximately 1,000 artists, thespians, writers, and critics assembled at Hibiya Park and marched to the Diet. At 5:15 p.m., as the column was marching from the Main Gate of the Diet to another gate to present petitions to sympathetic Socialist Party Diet members, the marchers were attacked by a large group of right-wing counterprotesters from the “Imperial Restoration Action Corps” (Ishin Kōdō Tai). The bulk of the assault fell on members of the Modern Drama Association (Shingekijin Kaigi), who were attacked by burly men wielding wooden posts embedded with nails in addition to having their column of marchers rammed head-on by two trucks emblazoned with right-wing slogans. The attackers were heard to yell, “We’ll kill you!” (koroshite yaru) and “Beat them dead!” (tatakikorose). In total, eighty people (fifty-one men and twenty-nine women) suffered injuries, including eleven who were hospitalized for three weeks or more. Most injuries were to the back of the head, and one actor suffered permanent hearing loss.

Just minutes later, on the other side of the Diet compound, leftist student radicals smashed through the South Gate and swarmed into the Diet. The police fell back and the students proceeded to give speeches and sing songs for more than an hour. But just after 7:00 p.m., the police massed and retaliated, driving the students back toward the gate. It was during this initial counterattack that a Tokyo University undergraduate, Kanba Michiko, was trampled to death. News of her death spread quickly, and enraged the students. The battle shifted to the Main Gate again, where the students repeatedly attacked and counterattacked long into the night.

Finally at 1:00 a.m., the police were given permission to take more forceful measures. Around 1:15 a.m., the police set upon the students, as well as a number of bystanders including middle-aged professors and reporters, with truncheons and tear gas. Photographs from that night show the youthful bodies of the students, having been beaten bloody and unconscious, being carried away to ambulances. The Diet compound was strewn with rocks, shoes, broken placards, and pools of blood and water, as well as eighteen wrecked paddy wagons the students had overturned and set on fire.

The June 15 incident horrified much of the nation, and most appalling of all was the death of Kanba Michiko. Although Kanba was neither the first nor the last person to be killed in a battle with police during the postwar period, her death was particularly shocking because she was from the upper-middle class, the daughter of a university professor, and she was a student at the elite Tokyo University. Thus, her death was seen to be particularly wasteful in a way that, say, a mineworker’s might not have been. Most importantly, however, she was female. Until 1922, women in Japan had been barred by law from participating in political meetings of any kind, and even in the 1950s, after they had been theoretically liberated by the 1947 constitution, women had typically been prevented from participating in protest marches, on the excuse that it was too dangerous. One reason women’s rights activists found the 1960 protests so inspiring was that, because they were viewed as a peaceful, broadly supported movement to protect democracy, many activist women were finally allowed to participate in protest marches for the first time in their lives (although in most cases, they were required to march at the rear, for safety). The unspoken subtext to the shock voluminously expressed over the general “violence” of June 15 was that whereas such violent clashes might be tolerated to an extent if they had involved only men, violence could not be countenanced when it involved women—Kanba Michiko in particular, but also the theater actresses from the Modern Drama Association who had been battered by the right-wing counterprotesters.

In any case, the escalation perpetrated by the students and right-wing hooligans on June 15 finally provided the shock necessary to bring down the Kishi cabinet. Kishi held out for an entire day following the June 15 bloodshed, conferring with his cabinet deep into the evening of the 16th. According to several eyewitness accounts, the head of the National Police Agency, Kashiwamura Nobuo, informed Kishi that in light of the recent violence, he did not have confidence that the police could guarantee President Eisenhower’s safety. Enraged, Kishi responded that if the police were not up to the task, he would have to call out the Self-Defense Forces to suppress the protesters and protect Eisenhower. Indeed, Kishi informed the Americans that one regiment (about 2,000 men) in the Tokyo area had already been placed on alert and that he planned to mobilize an entire division for Eisenhower’s visit.9 However, Defense Agency chief Akagi Munemori was strongly opposed, arguing that deploying the Self-Defense Forces would be a provocation that might instigate a popular uprising. Lacking the support of the two key figures of his defense chief and the head of the national police, Kishi was forced to give in, announcing that he would ask Eisenhower to “postpone” his visit, and indicating that he himself would resign following the final ratification of the treaty.

On June 18, the day before the treaty was due to be automatically passed by the upper house, the protests reached their greatest size. In Tokyo alone an estimated 330,000 demonstrators jammed the streets around the Diet. At first the protests were as boisterous as usual, but as the final deadline of midnight, June 19 approached, the crowds became solemn, as they realized that despite all their efforts, the movement had failed to block the treaty. It was, in the words of the writer and critic Takeda Michitarō, “a kind of magnificent funeral for the entire postwar experience.”10 Many of the protesters sat where they were in silence until dawn before finally going their separate ways, stunned that the expenditure of so much energy and enthusiasm had seemingly all been for naught. With the resignation of Kishi himself on July 15, the energy went out of the movement and the protests died away. However, the wide-ranging impact of the 1960 Anpo protests on US-Japan relations and Japanese politics, society, and culture was only just beginning.

Notes

The first time was on June 2, 1956, in a clash over the law that did away with the locally elected school boards established during the US Occupation in favor of more centralized decision-making at the prefectural level. On June 3, 1954, police entered the Diet building, but not the actual Diet chambers. See Eiko Maruko Siniawer, Ruffians, Yakuza, Nationalists: The Violent Politics of Modern Japan, 1860–1960 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2008), 143–150.

For example, Fukumoto Kunio, who at the time was the personal assistant of Kishi’s chief cabinet secretary Shiina Etsusaburō, recalled being dispatched by Shiina at the height of the crisis to meet with a group of top bankers at a geisha house in Yanagibashi where he was told, “The general desire of the financial world is that Kishi should resign and that Ike’s visit should be cancelled.” He was also told, “Please replace [Kishi] with Ikeda [Hayato].” When Shiina reported this to Kishi, Kishi reportedly became enraged and threatened to cut off loans from the Japan Development Bank. Fukumoto Kunio, Omote butai, ura butai: Fukumoto Kunio kaikoroku (Tokyo: Kodansha, 2007), 32–34.

Asahi Shinbun Hyakunen-shi Henshū Iinkai, ed., Asahi Shinbun shashi: Shōwa sengo hen (Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha, 1994), 289.

Quoted in Edward Whittemore, The Press in Japan Today: A Case Study (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1961), 54–55.

This incident is described in the records of the Tokyo District Court, which are cited in Tanaka Jirō, Satō Isao, and Nomura Jirō, eds., Sengo seiji saiban shiroku, 5 vols. (Tokyo: Daiichi Hōki Shuppan, 1980), 3:245–246.

See MacArthur to Department of State, June 10, 1960, in Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States 1958–1960, vol. 18, Japan; Korea, ed. Madeline Chi and Louis J. Smith (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1994), 331–332; and MacArthur to Department of State, June 12, 1960, reproduced in Documents on United States Policy toward Japan III: Japanese Internal Affairs as Seen by the American Diplomats, 1960, 9 vols., ed. Ishii Osamu and Ono Naoki (Tokyo: Kashiwa Shobō, 1997), 2:219–222.

MacArthur to Secretary of State, June 16, 1960, White House Office Records, Records of the Staff Secretary 1952–61, International Series, Box 9, Folder “Japan—Vol. III of III (1),” Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library.

Quoted in Mainichi Shinbunsha, ed., Iwanami Shoten to Bungei Shunjū: Sekai, Bungei Shunjū ni miru sengo shichō (Tokyo: Mainichi Shinbunsha, 1996), 323.