Abstract: In the unfolding of a global pandemic that has wreaked havoc worldwide, another less obvious pandemic hovers overhead. This is what the United Nations is calling a ‘Shadow Pandemic.’ A rise in domestic violence within households has been noted in Japan and other countries. The stay-at-home measures to prevent the spread of the infection have essentially kept victims trapped with abusive partners and few means of escaping to the often-closed manga cafes or women’s shelters. In this dire time, Japanese laws offer only minimal protection. This article draws on insights from Nakajima Sachiko of NPO Resilience, which aims to spread awareness of domestic violence and the effects of this trauma. She shares her expertise in the field and experiences as a survivor herself on the mechanisms that exist in Japanese laws and society that have created increased vulnerability among victims. Domestic violence in Japan is an area needing stronger attention from the government and legal system.

Keywords: Corona, COVID-19, Vulnerable populations, Domestic Violence in Japan, Gender Inequality, Violence against women, Resilience

Voices of domestic violence victims in the context of COVID-19

The initial state of lockdown in Japan began on April 8, 2020, due to the number of infections of the novel coronavirus rapidly spreading throughout cities in Japan, with Tokyo as the primary hotspot. Since then, incidents like the following have been increasing in Japan:

The cash handout of ¥100,000 promised by Prime Minister Abe Shinzo is meaningless for most victims of domestic violence. Even if she left her husband now, she could not transfer her residence in time to receive it – any benefits would be received by the head of the household, who is her tormentor: “I can’t apply for financial support directly under my own name, I’m afraid to do it.”

These are some of the raw voices of victims of domestic violence in Japan. They were collected by the All Japan Women’s Shelter Network, and included in a letter to the Japanese government (Kitanaka, 2020) requesting increased protective measures for victims of domestic violence and child abuse under the coronavirus countermeasures.

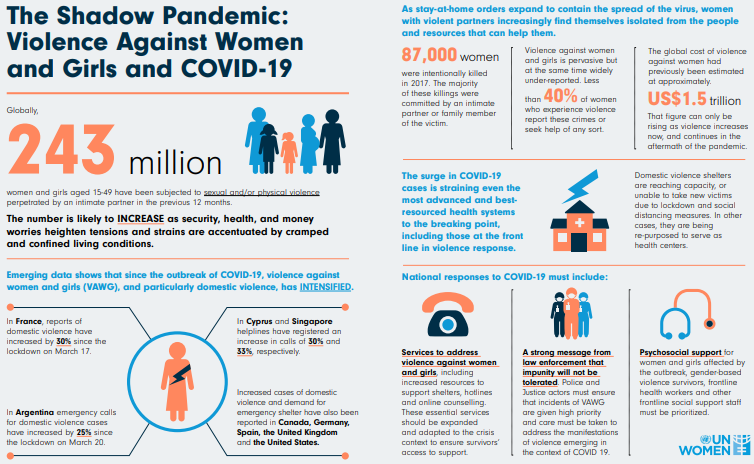

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the whole world and has triggered horrific consequences on much of society within a short span of time. While the world is at a stand-still, it has become apparent that further issues lurk behind closed doors for victims of domestic violence. The UN has referred to this as a “Shadow Pandemic” (Mlambo-Ngcuka, 2020). The stay-at-home measures meant to keep the virus from spreading have caused an increase in cases of domestic violence globally. Japan is no exception to this trend, as shown in the increasing media coverage on the rising number of cases in Japanese households since the lockdown. By the end of April, the Japanese government had set up a 24-hour hotline NPO service, DV Soudan+ (“DV相談プラス|内閣府 DVのお悩みひとりで抱えていませんか?” (Cabinet Office 2020) in ten different languages to provide support for victims of domestic violence. While expert Sachiko Nakajima, founder of the NPO Resilience which aims to spread awareness of domestic violence and the effects of trauma, calls this a step in the right direction, she also points out that not enough is being done to support victims. “It’s not a surprise,” she says, that the government is doing so little. After all, their idea of systematic prevention is to mail out two masks per household. That’s the extent of their imagination; it’s too big a stretch to go from there to thinking of survivors of abuse in homes.”

This article outlines some of the dangers currently faced by victims of domestic violence in Japan in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

History of domestic violence in Japan

Laws regarding domestic violence in Japan Pre-corona support structures

The Japanese law regarding domestic violence is still relatively new, with some small changes having been made in the past few years. The Prevention of Spousal Violence and the Protection of Victims; DV Prevention Act was implemented in April 2001 (Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office nd a) According to the law, the definition of “spousal violence” refers to physical harm inflicted by one spouse on another and acknowledges verbal and emotional abuse. It applies when a spouse is subjected to violence by the other, even after a divorce or annulment of the marriage occurs. In 2013, the law was adapted to include cases where the term “spouse” is applied in a de facto state of marriage that had not been registered legally (Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office). This revision means that spouses can refer to those that are not legally married but share a life together including the victims’ boyfriends or girlfriends. Additionally, this law would also apply to foreigners living in Japan, regardless of their formal status of residence.

According to the Bureau, “When women who find it difficult to achieve economic self-reliance are subject to violence from their spouses, it adversely affects respect for individuality and impedes the realization of equality between women and men.” The law was last amended in June 2019, so as to include child abuse in homes and to strengthen child support for those affected.

While laws relating to domestic violence have seen some change, in 2017, for the first time in 110 years, there was a further amendment in the law on rape. The initial law stated in Article 177 of the penal law that rape is when “a person forcibly inserts a male sex organ into the female sex organ of a woman or girl over thirteen years old” (Yatagawa & Nakano, P.9, 2008). The law was finally revised to include both forced anal and oral sex (Kitagawa, 2018). The change now also accounted for rape victims to potentially be men, and includes consideration of the rape of a person below the age of eighteen by a parent or guardian even in the absence of physical violence, intimidation, or attempts to resist. The punishments were also increased, with a minimum prison sentence increased from three years to five, and the possibility that prosecution could take place even in the absence of charges by a victim. Although rape can occur in marriage if the act is forced, the penal code does not specifically address this, leaving married abuse victims of sexual violence vulnerable.

Japan in comparison to OECD countries

In a global perspective, Japan is known to have high gender inequality, ranking at 110 out of 149 countries in the 2018 World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap Report (World Economic Forum, 2018). Domestic violence in Japan is relatively common and reports of cases have been rising for 16 consecutive years with an all-time high of 9,161 reported cases in 2019 (Kyodo, 2020). If we examine Japan in relation to other OECD countries, several patterns emerge.

Domestic violence in OECD countries

The chart below shows data measuring the percentage of women who reported violence physically or sexually by an intimate partner in 2019. The United States is where women have experienced the highest reported level of violence from their intimate partners (36%), whereas Canada has the lowest (1.9%). In Japan, approximately 15% of women reported having experienced violence from their partner in 2019. The OECD average in 2019 was around 21% – putting Japan below the average. Nevertheless, in addition to the fact that the number of reported cases is increasing each year, it is likely that the coronavirus will increase the number of cases (Osumi, 2020). As has been widely reported, there are numerous cases in which victims are reluctant to admit they have been abused, leading to inaccurate data (Nippon.com, 2018).

Domestic violence law in OECD countries

Compared to other OECD countries in terms of legislation that protects victims of domestic violence, Japan does not stand out as a leader in combatting such abuse. However, it does have laws and standards. The graph below measured the OECD nations’ laws and assesses whether they had effective legal frameworks to protect women from violence (including spousal). In this chart, 0 means that women are protected comprehensively without any legal exceptions, and 1 indicates that no legal framework protects women. Japan is ranked at 0.75. That is, Japan has laws in place addressing domestic violence, but those laws do not protect all women and have legal exceptions. Many other OECD countries such as Australia, Germany, and the UK have similar exceptions while others like Canada provide more inclusive protections.

The Prevention of Spousal Violence and the Protection of Victims Act (2001) is the existing law, yet Japanese women remain vulnerable. The law stipulates that in the case of a claim made by a victim, the alleged perpetrator is required to vacate the site of primary shared residence for a two-month period from the day on which the order goes into effect. However, after that, in an astonishing ruling, the claimant (that is, the victim, not the perpetrator) must vacate the house. Nakajima explains that in effect it is a “pack and leave” order for the victim. This law punishes the woman with eviction from her own home for making a claim against a husband who is putting her life in jeopardy.

While this gendered pattern of victimization is not distinctive to Japan, it is enshrined in law through the Japanese family registry system or koseki (戸籍) system. In more than 95 percent of families, males are officially the head of the household, and even when laws are passed that supposedly protect female victims, such as Article 10 above, the effect is that women get driven out of their own homes for reporting domestic violence. Nakajima claims that, “It’s as if women are considered to be property under some laws” in Japan, due to laws remaining in place that disempower women. The dangerous effects of this situation are particularly evident in the context of the coronavirus, with women having to vacate their homes in a time of nationwide infection. As noted above, this is the reason that many women are unable to receive their 100,000 yen compensation checks from the government because they are issued to the head of the household, who would be the abusive spouse.

Attitudes toward domestic violence in OECD countries

Attitudes toward domestic violence in OECD countries differ. Chart 3 shows findings collected from women aged 15-49 years old as to whether, and under what conditions, violence by husbands was justified. Countries like Germany (19.6%) and South Korea (15.4%) were remarkably high, while only 8.9% of the Japanese participants felt that spousal violence was sometimes justifiable. However, Denmark (0%) and Ireland (1%) set standards for extremely low tolerance for violence against women. Japanese attitudes about domestic violence are mixed, in part due to women’s weak social position and the lack of space for open discussion on this topic between partners. Nakajima claims that “abuse and attitudes toward abuse are tied to the power disparity between genders,” explaining Japan’s “gender inequality ranking is circumstantial evidence for that. Those things are not separate issues.” Until the gender inequality problem is resolved, domestic violence will remain at high levels.

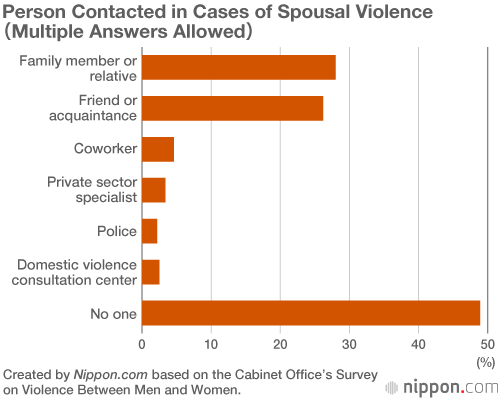

Although the number of reported cases in Japan may be increasing, there is evidence (see chart 4) that the actual number of incidents is much higher than reported. This can be seen in the graph below where, according to the Cabinet Office’s Survey on Violence Between Men and Women, only 2.2% of women who experienced domestic violence actually reported their case to the police, while nearly 50% of participants did not tell anyone. Therefore, the true extent of the scale of the rates of domestic violence is still unknown, with many victims continuing to suffer in silence.

Domestic violence under Corona

Japan was experiencing an increase in cases of domestic violence even before the pandemic began. The Prevention of Spousal Violence and the Protection of Victims Act was passed in 2001, and the amount of reporting has been rising steadily since 2003. The graph in chart 5 below shows cases of spousal offences from 2008 to 2017 compiled by the Ministry of Justice (“White paper on crime 2018”). There was an all-time high in 2019, with reported cases of domestic violence recorded at 9,161 (Nippon.com, 2018). Many activists expect that the increase in violence in households due to the pandemic will lead to a 17th consecutive annual increase in cases. An official in Tokyo, employed by a domestic violence local consultation center, claimed to have received 23 calls for help in March. This is considerably higher than the previous year where reports for the number of calls for help averaged fewer than 10 per month (Osumi, 2020). It was also reported that from April, besides the already existing public hotline, more avenues would be created to support domestic violence survivors, indicating the government’s recognition of domestic violence as an ongoing issue (The Mainichi, 2020).

Nakajima explains that there seems to be a strong tendency to “self-blame” by Japanese victims, in this case, for female victims of domestic violence to blame themselves for the violence perpetrated upon them. Nakajima is a survivor herself and suggests that this tendency stems from the particular notion of accountability that is prevalent in Japanese culture. She explains that when women confide in others about their abusive partners, they are often told that the abuse is her fault or that she is to blame for having chosen that partner. The notion of self-responsibility (自己責任 jiko-sekinin) is reflected in such reactions by others.

Interestingly, she links this reaction to the way that Japanese as a whole think about COVID-19. She notes, it is “similar to how people react to those who have contracted the virus with comments such as, ‘you caught the virus because you were not careful enough.’”

She recognizes that while this is not unique to Japan, many Japanese women feel a particularly strong sense of responsibility for their circumstances. This can be seen through the data in relation to chart 4, where over 34% of victims cited the reason for not seeking help was that they felt that they were to blame for the abuse (Nippon.com, 2018).

The increase in reporting of incidents correlated with numerous factors, but does not necessarily prove that there has been a spike in domestic violence. Instead, Nakajima believes that, at least until the years prior to the onset of the coronavirus emergency, victims were choosing to report their cases more often. One reason that more are reporting their condition could be the increase in availability of technology and social media platforms which allow more women to connect and share their stories and seek advice in relative anonymity. An example of this can be seen in Yahoo’s forum called Chiebukuro (wisdom bag) where anonymous women share experiences of their abusive husbands and ask for advice. Still, many choose to keep their personal affairs private and hidden from society, leaving many victims to feel that their case is unique when it may be relatively common.

Awareness of domestic violence has also increased through the media. During the coronavirus pandemic there has been extensive coverage of cases of abuse taking place in households. Most of the major newspapers in Japan ran editorials about the issue of domestic violence under the coronavirus, ranging from the Japan Times mentioned above (Osumi, 2020) to the Asahi Shimbun with their editorial “‘Stay home’ order needs to consider victims of domestic violence” (The Asahi Shimbun, 2020), and the Yomiuri Shimbun with theirs “Strengthen the system for grasping corona and DV damage” (Yomiuri, 2020).

Aizawa (2020) and others have covered this topic since April when the limited lockdown began. In recent years, although less successful compared to a number of other countries, the #Metoo movement did have some success in bringing to light women’s stories of mistreatment. The most prominent example is the case of journalist Shiori Ito, who came forward with her story of rape by a leading journalist despite the taboo and stigma surrounding rape. This set a precedent which emboldened other women to open up about their stories of abuse and harassment, leading to some high-profile stories such as that of model KaoRi sharing her maltreatment by renowned erotic photographer Nobuyoshi Araki (“When Japan’s women broke their silence”, 2020).

Nakajima states that the more empowered women are, the more likely they are to report abuse. Empowerment can come from recognition that the abuse is not their fault. However, Nakajima also notes that there is not enough professional knowledge and support to assist victims regarding trauma and domestic violence. She claims that many care providers, such as therapists and counsellors as well as law enforcement, medical personnel, lawyers, judges, and others in Japan are not educated on the subject, hindering progress in exposing domestic violence and assisting victims. NPO Resilience holds seminars and lectures on abuse, harassment, and trauma to enhance understanding of how trauma can affect survivors and to lessen the confusion that abuse can bring. Despite these efforts, the level of knowledge remains low, and institutional response leaving something to be desired.

Support for victims of domestic violence during a coronavirus pandemic

The term “Shadow Pandemic” coined by the UN refers to the global rise in domestic violence cases worldwide. As explained by United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, the irony lies in the fact that even as people are encouraged to stay at home in order to stay safe, “the threat looms largest where they should be safest: in their own homes” (2020).

Victims of domestic violence were already vulnerable prior to the pandemic. However, when the perpetrator or spouse left the house for work, the victim was able to have some sense of freedom and respite from abuse. Sadly, since stay-at-home policies were enforced, the home became a perpetual danger zone for domestic violence victims. Mass media has brought these issues to the awareness of the Japanese public. The Yomiuri Shimbun reported in April that there was an increase in the reporting of domestic violence in Japan (Yomiuri, 2020), although the exact numbers were not given. Instead it focused on collecting voices of the victims. As many articles point out, in instances when the perpetrator is always at home and out of work, often with financial anxiety, the chances of domestic violence increase; where children are also at home, the situation can become even worse. Other Japanese media outlets have been increasing coverage of domestic violence amidst the coronavirus, including cases of national celebrities. Actor Makoto Sakamoto was arrested on March 30 for allegedly assaulting his wife (Osumi, 2020), while more recently TV personality Bobby Ologun was arrested under similar circumstances on May 15 (“TV personality Bobby Ologun arrested on domestic abuse charge,” 2020). In both cases, the actors denied the allegations of abuse.

The situation in every household is different, but the coronavirus has adversely affected everyone. The uncertainty has created increased stress, further triggered by a sense of future instability, often with regard to financial difficulties that may arise in a recession. Chisato Kitanaka, head of the All Women’s Japan Shelter Network suggests that low-income or poor households are likely to be most susceptible. “This is especially the case with people who felt secure in their role as the main earner and the head of household. They lash out and attack their partners” (Aizawa, 2020). With everyone requested to stay at home to prevent the spread of infection, new forms of telework have emerged. This can cause stress in marriages or relationships in general, as partners spend more time together and are forced to address issues that may have been present previously. The term #coronarikon (coronavirus divorce) has been trending on SNS sites such as Twitter. There is even a new service that provides spouses separate accommodations to prevent divorce. Kitanaka claims that even couples that had no previous experience of domestic violence sometimes experienced an outburst during the pandemic (Aizawa, 2020).

Nakajima expressed concern that during the coronavirus pandemic, individuals living in violent households could suffer an amplified sense of fear. Perpetrators gain control by being more present as they work from home. The greater level of stress caused by the pandemic also gives them a way to “justify their abuse” of spouses. The psychological effects of COVID-19 can overlap or intensify when a victim has been traumatized by past incidents of abuse. What makes the reality even more difficult is that this situation can feel as if there is no “light at the end of the tunnel” as Nakajima states, since there is still no reliable cure, and we do not know how much longer the pandemic will last or whether there will be a resurgence in the autumn. Consequently, the pandemic can trigger an overwhelming sense of fear and isolation in survivors. The situation can also be intensified when substance abuse occurs. Vicki Skorji, director at TELL (Tokyo English Life Line) Japan noted, “if drinking is one of the partners’ coping mechanisms, things can get out of control quickly.” A recent newspaper article covered the incident where 59-year-old Kazuo Makino was arrested in early April for murdering his 57-year-old wife at their home. He claims he was provoked in a drunken argument about their finances. When he physically attacked her, she died shortly after (Ryall, 2020).

In reference to government support, Nakajima mentions that the government-provided hotline is useful. Nevertheless, there is much room for improvement in providing support during the pandemic. Nakajima states that since therapy is not covered by insurance, many victims have to rely heavily on the government hotlines. Especially during this time, with an increase in violence in households, she fears that even with the release of the new hotline, demand will be too high. Plus, she fears, not all survivors may be able to access the help that they need via the hotline.

In a time where victims are most vulnerable, there is dwindling external support as shelters throughout the nation have had to close. Traditional escape outlets such as net cafes or local government agencies have also been shut down as they were considered high-risk for spreading the disease (Akazawa, 2020). Shelters and domestic violence consultation services have also closed in response to the lockdown, which has further impacted the victims that desperately need their support. Kitanaka requested in her letter to the government that they reopen these services and open additional shelters for victims who need to evacuate (Kitanaka, 2020, p.1). Kitanaka also requested financial assistance and cash handouts be more easily accessed by victims of domestic violence who had to evacuate but had not yet had the chance to change their residential registry. She also begs the government to “be flexible about providing benefits to those without bank accounts,” (Kitanaka, 2020, p.2) as many wives in Japan use an account in their husband’s name.

Conclusion

While NPOs such as Resilience and TELL are working tirelessly to raise awareness about domestic violence and trauma within society, the government of Japan still has far to go in terms of systematically addressing such abuse. Despite the feeling that the pandemic is winding down, there is little to suggest that domestic violence survivors who suffered during the state of emergency would be more willing or able to advocate for their rights and seek support from the government and other sources. It could actually be that domestic violence victims in Japan will be less likely to speak up, and the government, preoccupied with the economic crisis, will not pay enough attention to those who are in desperate need of help and resources. On the other hand, there is a possibility that, through the collective experience of social isolation, more people will empathize with survivors who feel alone and misunderstood in their abusive relationships. With the rise of “corona divorce” (coronarikon), perhaps there will be less stigma associated with getting divorced from an abusive spouse. This could encourage victims to remove themselves from a violent marriage or partnership and instead seek separation or divorce. Should there be a resurgence of coronavirus, the government should use the experience of the past few months to better equip itself to deal with issues like domestic violence and child abuse, beginning with expanding crucial institutions such as counselling offices and shelters when they are most needed. Although Nakajima does not expect major changes regarding domestic violence issues in the short term, she hopes that the lessons society has learned during this COVID-19 crisis can bring about positive changes in how domestic violence is handled in Japan.

NPOs and organizations supporting survivors of DV in Japan

References

Aizawa, Y. (2020, April 24). “Shadow pandemic” of domestic violence spreads around the world”, NHK WORLD JAPAN News. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Akazawa, S. (2020, April 16). Net Cafe Refugees, Metropolis Magazine Japan. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Cabinet Office (2020) DV相談プラス|内閣府 DVのお悩みひとりで抱えていませんか?(DV Consultation Plus|Do you have any concerns about DV?) (2020). Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Corona rikon (2020).「コロナ離婚防止の窓口」公式サイト. “Corona Divorce Prevention Counter” official website (2020). Retrieved 26 May 2020.

DVとして助けを求めるべきでしょうか。こちらに原因があっても普通は暴力は振るわないものですよね?わからなくなってきました。私は、妊娠5ヶ月に入る22歳です。彼は34… (Should I seek help as a DV? Violence usually does not work even if it has a cause here, right? I’m not sure. I am 22 years old who is 5 months pregnant. He is 34…) (2013). Retrieved 26 May 2020,

“Efforts needed to detect violence at home as Japan asks people to stay indoors.” (2020, April 22). The Mainichi. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

“’Stay home’ order needs to consider victims of domestic violence.” (2020, April 22) The Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

e-Gov法令検索. (2020). Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office, (nd a ). 配偶者暴力防止法の平成25年一部改正法情報 | 内閣府男女共同参画局. (Information on Partial Amendments to the Spousal Violence Prevention Law in 2013 | Gender Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office.) (2020). Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office, nd b b). 全文(英語)配偶者暴力防止法の令和元年一部改正情報 | 内閣府男女共同参画局. (Full Text (English) Partial Revision Information for the Spouse Violence Prevention Act in 1991 | Gender Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office) Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Gender, Institutions and Development Database (GID-DB) 2019. (2020). Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Kitagawa, K. (2018, Feb 6). Recent Legislation in Japan No.2 “Penal Code Amendment Pertaining to Sexual Offenses.” Institute of Comparative Law, Waseda University. Retrieved 26 May 2020, from

Kitanaka, C. (2020, Mar 30). Request for the Prevention of Domestic Violence and Child Abuse under the Condition of Novel Coronavirus Countermeasures. All Japan Women’s Shelter Network.

Kyodo. (2020, Mar 5). “Domestic violence cases in Japan reached new high in 2019.” Japan Times. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Mlambo-Ngcuka, P. (2020, April 6). “Violence against women and girls: the shadow pandemic.” UN Women. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

“#MeToo Japan: When Japan’s women broke their silence.” (2020, April 25). BBC. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

NPO法人レジリエンス (2020). Retrieved 24 May 2020.

“Only a Fraction of Domestic Violence Victims Contact the Police.” (2018, Aug 27). Nippon.com, Nippon Communications Foundation. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Osumi, M. (2020, April 6). “Curbs to stem COVID-19 in Japan may fuel domestic violence and abuse.” Japan Times. Retrieved 26 May 2020, from

Ryall, J. (2020, April 22). “In Japan, coronavirus crisis traps families at home with domestic abuse.” South China Morning Post (SCMP). Retrieved 26 May 2020.

TELL Japan. (2020). Retrieved 26 May 2020.

“TV personality Bobby Ologun arrested on domestic abuse charge.” (2020, May 17). Japan Today. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

UN Women. (2020). The Shadow Pandemic: Violence Against Women and Girls and COVID-19.

White paper on crime 2018. Ministry of Justice Japan. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

The Global Gender Gap Report 2018. (2018). World Economic Forum.

The Yomiuri Shimbun (2020) コロナとDV被害把握する体制を強化せよ : 社説. (Corona and DV strengthen the system to understand damage: Editorial) (2020). Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Yatagawa, T. & Nakano, M. (2008). “Sexual Violence in Japan: Challenging the Criminal Justice System.” WOMEN’S ASIA, Voices From Japan, (21).