Abstract: In 1901, British traveller Charles Henry Hawes (1867‒1943) made a journey down the Tym’ River on the island of Sakhalin, visiting villages occupied by indigenous Nivkh and Uilta people along the river and at its mouth on the Sea of Okhotsk. The island was at that time under Russian control, and had become notorious as a penal settlement, but Japanese influence was also strong: four years after Hawes’ visit, following Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, the southern half of the island would become the Japanese colony of Karafuto. Hawes had some ethnographic knowledge, but arrived in the island as an interested amateur, more concerned to record his encounters along the route than to develop any particular ethnographic theory. For that reason, he recorded what he saw with an unselective immediacy which sheds light on the fluid and dynamic interactions between indigenous communities, Russian colonisers, Japanese mercantile and fishing interests and other groups. While Hawes’ published book, In the Uttermost East, has been used as a source by some scholars of the region, the notebooks that he kept on his travels have lain for years in the Bodleian Library, largely unnoticed by researchers. This article uses these notebooks, Hawes’ published work, and photos that he took or collected on his travels, to shed light on aspects of indigenous society in Sakhalin at a crucial moment in its history.

Keywords: Sakhalin, Karafuto, Nivkh, Uilta, Ainu, Evenk, Charles Henry Hawes, Bronislaw Piłsudski, Lev Shternberg, indigenous peoples, Russo-Japanese relations.

It is late on a September day in 1901, and British traveller Charles Henry Hawes is sitting on a sandbank by the shores of Chaivo Bay, on the Russian controlled island of Sakhalin, awaiting the arrival of the local shaman. The sun is setting over the hills behind him, and the Pacific Ocean ‘rolling in through the strait close by’.1 About twenty local villagers have gathered near the log fire that is blazing on the beach. A photo which Hawes brought back with him from his travels shows the scene – Hawes himself, at the left, bent over his little portable table, busily scribbling notes, while the others around him laugh, frown, chat to one another or pat their dogs. Fish are hanging up to dry on a wooden rack at the top of the sand dune, and some of these have been skewered and are being cooked over the fire for the evening meal. Most of the people in the photo are members of the Nivkh language group, though some may also be Uilta. The two groups inhabit separate villages dotted around the bay – trading and intermarrying with one another, but speaking unrelated languages and each living according to their own customs. (Uilta culture, for example, is closely associated with the herding of reindeer, while Nivkh communities rely more heavily on dogs for hunting and transport2).

Hawes does not speak either of the local languages, and his Russian is fairly rudimentary, so his conversation with the villagers is taking place via interpretation, provided on this occasion by an oil prospector who has spent several years in the district (and who probably also took the photograph). Once the shaman arrives, Hawes tries to ply him with suitably ethnographic questions, but the conversation keeps veering off in unexpected directions. Hawes asks the shaman whether he ever heard from his forebears where the earliest Nivkh came from, but the reply is vague: ‘over the hills there – west’. And before replying the shaman has his own question to pose: ‘could we tell him how the Russians came to be here and living in towns (not in forest)?’ Hawes’ reply is not recorded. Meanwhile, another elderly Nivkh interjects his own answer to the foreigner’s question: ‘How can I tell? [Neither] my father nor my grandfather could write and so they have left no writing to tell, and I cannot read, so how can you expect me to know?’3 The answers Hawes receives do not always seem to match the questions he has asked, and he finds himself wondering how much the interpreter is interjecting his own opinions into the dialogue.4 But the evening ends with shared laughter, and with Hawes sleeping in the house of the (Russian appointed) Nivkh headman, surrounded by seal skins, bark baskets, tea cups from Russia, bowls from Japan, fishing equipment, a few guns, and a portrait of the late Czar Alexander III on the wall.5

C. H. Hawes (far left) with local villagers on the shores of Chaivo Bay

(from In the Uttermost East, opposite p. 233)

Charles Henry Hawes’ writings are not the most informed or detailed accounts of the lives of Sakhalin’s indigenous people at the start of the twentieth century. The Russian ethnographer Lev Shternberg (1861‒1927) and his Polish friend Bronislaw Piłsudski (1866‒1918), both of whom lived on the island for years as political exiles, provided far more extensive and accurate information: Shternberg focusing particularly on the study of Nivkh communities, and Piłsudski on the Sakhalin Ainu (Enchiw) (though both also conducted studies of other indigenous groups).6 Hawes, by contrast, was only in Sakhalin for a few weeks, and derived a substantial part of his ethnographic information from Shternberg and Piłsudski. He examined and photographed the display of indigenous artefacts which Piłsudski and others had collected for the small museum in Aleksandrovsk7, and soon after his departure from Sakhalin, he met Piłsudski in Vladivostok (where the Polish ethnographer was then living) and was introduced to Endyn – a Nivkh teenager whom Piłsudski had taken to the city to be educated, but who, sadly, was to die soon after from tuberculosis.8 Hawes greatly admired Piłsudski, and continued to correspond with him after his return to London.9

The Sakhalin Regional Museum, Aleksandrovsk, around the start of the 20th century (original possibly by Ivan Nikolaevich Krasnov10) (Library of Congress, control no. 2018684056).

But, precisely because he was not an expert – just a traveller on the trip of a lifetime – Hawes recorded what he saw with an unselective immediacy that opens an intriguing window into life in northern Sakhalin at a crucial moment of its history. Scholars like Shternberg, Yamamoto Yūkō and Ishida Eiichirō11 wrote analyses of the lives of the region’s indigenous people which (influenced by the traditions of Malinowski, Boas and others) were couched in ‘the ethnographic present’. That is to say, they wrote in the present tense, but the ‘present’ which they depicted in their works was not the world that they actually observed during their fieldwork. Instead, it was a reconstructed image of ‘traditional’ indigenous life which screened out inconvenient aspects of the colonial present in order to highlight cultural features that illustrated ‘their normative view of what the native is about’.12 This approach has since been widely criticised by anthropologists as obscuring the complex and dynamic reality of indigenous societies. But attempts to write the history of places like Sakhalin are hampered by the fact that so much of the available early twentieth century material on these societies is couched in the ethnographic present. The problem is compounded by popular journalistic and travel writings, which often not only reified but also sensationalized the ‘primitive’ and ‘exotic’ features of indigenous cultural life.13

Hawes observed the societies of the region with a relatively scholarly eye, but had no particular ethnographic theory that he wished to prove, and therefore had relatively little interest in extracting a ‘pure’ traditional culture from the messy realities which he encountered on his travels. His diaries and published book do not depict the ‘ethnographic present’, but rather give glimpses of a multilayered and rapidly changing world where indigenous people sought paths to survival that repeatedly crossed the boundary lines between older modes of subsistence and the new social and economic forces introduced by the two rival imperial powers: Russia and Japan. And (as we shall see) the older modes of subsistence themselves had been dynamic and involved complex trading and cultural links with neighbouring societies. By chance, Hawes visited Nivkh and Uilta communities which Piłsudski was unable to reach on his major study tour of indigenous villages in 1903‒1905,14 and because he was on a journey of exploration rather than seeking to study the culture of one specific group, Hawes observed the very close interconnection between different cultural groups which was a vital feature of Sakhalin’s past and present.

The immediacy of Hawes’ account is particularly evident in the notebooks which he kept during his travels, and which were later transcribed by his daughter and given to the Bodleian Library in Oxford. In this essay, I shall use these long-neglected notebooks, together with Hawes’ published account of his journey, to explore aspects of the region’s indigenous history in the modern era, and to consider the wider question of indigenous responses to the imperial rivalries that divided their traditional homelands. These unpublished diaries shed light on the fluid and dynamic interactions across social groups in North Asia at that time, while highlighting the problems of communication, interpretation and (mis)understanding that emerge from encounters between indigenous communities, travellers, guides and interpreters in many early twentieth-century travel writings. They also challenge us to think about the processes by which twentieth century travel writings were produced, and about the responses that those writings evoke from us, their readers in the twenty-first century.

Sakhalin’s Indigenous People in the Age of Empires

In 1901 Hawes found himself, almost by chance, in a world on the cusp of massive change. The island of Sakhalin had been loosely linked to the outermost fringes of the Chinese empire in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and since the first half of the nineteenth century had become the focus of fierce imperial rivalries between Russia and Japan. Between 1855 and 1875, the island was under the joint control of these two emerging empires, but in 1875 Japan had relinquished its claims, in return for control over the Kurile Islands to the east. At that time, over one-third of the Ainu population of southern Sakhalin was persuaded to leave from Hokkaido, where large numbers soon died from epidemics of cholera and smallpox. Japanese influences in Sakhalin remained strong, though, and by the time Hawes arrived on the island tensions between the imperial powers had become acute.

Three years later, these tensions were to ignite the Russo-Japanese War, which resulted in defeat for Russia. As part of the spoils of war, the island of Sakhalin was bisected along the 50th parallel (roughly half-way up its length) with the southern half being handed over to Japanese control. Between 1921 and 1926, during its post-Russian Revolution intervention in Siberia, Japan briefly extended its control to the whole of the island, but with the exception of this interregnum, Sakhalin was to remain divided between Japan and Russia until 1945, when the Soviet Union regained control of the whole island – a control which Russia retains to the present day.

Eastern Siberia, Sakhalin and Kamchatka

(CartoGIS CAP, Australian National University)

These power shifts had a profound and often devastating impact on the lives of the indigenous Nivkh, Uilta and Ainu communities who had inhabited the island for centuries. The ancestors of the Nivkh (whom Hawes, like other European contemporaries, referred to as the Gilyak) are now generally believed to have lived in Sakhalin and in the area of the Asian mainland around the mouth of the Amur River at least since around 1,000 BCE.15 Their language is unrelated to that of surrounding groups. The Ainu are thought to have ancestral roots going back to the people who inhabited the Japanese archipelago and surrounding areas (including the southern part of Sakhalin) in the Jōmon Period (c. 10,000‒400 BCE). By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries of the common era, there were also small Ainu communities living throughout the Kurile Islands living in the south of the Kamchatka Peninsula and around some stretches of the Amur River on the Asian mainland.

The reindeer-herding Uilta (also known as Ulta, and referred to by Hawes as ‘Orochon’) are more recent arrivals in Sakhalin, migrating there from continental Asia long after the Ainu and Nivkh were established on the island, but sometime before the beginning of the 18th century CE.16 Their language is closely related to that of other so-called ‘Tungusic’ groups such as the Evenk, Nanai and Ulchi of the Siberian mainland. Indeed, Sakhalin Nivkh, Ainu and Uilta all had ongoing interactions both with one another and with other mainland Asian indigenous communities. As Richard Zgusta writes, in recent centuries the whole population of the Amur region and Sakhalin has constantly been ‘in a state of flux, and groups of different lineages speaking various dialects and languages separated from and joined each other with relative ease and without much conflict.’17

In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries (as we have seen) these indigenous groups became the focus of study by many anthropologists and archaeologists, who sought to unearth and define the key features of their traditional cultures and trace their genetic ancestry, sometimes also incorporating them into their imperious hierarchies of human evolution and progress.18 Bronislaw Piłsudski was unusual in being an ethnographer who was not only interested in traditional cultural patterns, but was also deeply concerned with the contemporary wellbeing of the indigenous people, and wrote in detail about the impact of Russian rule on their lives.19 More recently, researchers have become increasingly interested in the dynamic place of indigenous people in the region’s modern history: their role as active agents in a rapidly changing society, adapting creatively as they struggled to survive colonization, wars, exploitation and displacement.20

The story of these Sakhalin communities echoes those of indigenous groups across the globe. The destruction of habitat, the expropriation of land, the suppression of culture and the devastation wrought by imported epidemic diseases are themes repeated worldwide. In Sakhalin, though, the indigenous people had the added challenge of dealing with two rival colonizing powers whose influence waxed and waned with changes in the global power balance. At the same time, the complex relationships among the various indigenous groups themselves changed in response to shifting patterns of colonialism. Vivid images of these changes emerge from the world observed by Charles Henry Hawes on his 1901 travels in Sakhalin.

H. Hawes’ Journey to Sakhalin

C. H. Hawes on (or preparing for) his travels in Siberia

(from In the Uttermost East, opposite p. 428)

Henry Hawes (he was generally known to his family by his second given name) arrived at Chaivo Bay as a result of a series of rather unusual fortuitous events. Most European travellers in East Asia at the start of the twentieth century came to the region either for professional reasons – as diplomats, journalists, missionaries etc. – or because they had inherited wealth which allowed them to travel when and where they wanted. Hawes was an independent traveller, but had not been born into wealth. His father was a suburban London commercial traveller who later became a shop fitter, and Henry was one of a family of eleven children. Born in 1867, Henry attended the City of London School, and then found work as a clerk for a stationery wholesaler21, and in 1889 he married Caroline Maitland Heath, a well-to-do school teacher who was 26 years his senior: he was 22 and she was 48 at the time. Despite the gap in their ages, the evidence suggests that this was a love match. When Caroline became terminally ill not long after their marriage, Henry ‘nursed her most tenderly through the dreadful, prolonged agony of cancer which ended her life’.22 On her death, Caroline left her young widower almost £5000 – worth over half a million pounds in today’s money – and Henry, then in his late twenties, chose to invest his new-found wealth in two things: education and travel. In 1896, he entered Trinity College Cambridge as a fee-paying student, and not long after graduating, he set off in October 1900 on a fourteen-month journey which took him to India, Burma, Ceylon, Australia, New Zealand, China, Japan, Korea, and Siberia (including Sakhalin).

A photograph of Hawes wrapped in furs for his Siberian travels exudes the image of a romantic hero of turn-of-the-century exploration, but the description of her father provided by Mary Allsebrook, Hawes’ daughter by his second marriage, gives a rather different picture:

A self-effacing man, only five feet six inches tall and just over eight stone (a hundred and fifteen pounds) at his heaviest, he did not appear cast for adventure. He had good looking and kindly features, very blue eyes, and brown hair which he kept closely cut to discourage it from curling. He dressed very quietly, correctly, and only went in for bright colours in his pyjamas… A man less likely to carry a gun one can hardly imagine. But carry one he did during much of his visit to the Russian penal colony on Sakhalin.23

Hawes kept journals and notebooks throughout his travels, and later expanded parts of these into fuller manuscripts, some of which he included in his book To the Uttermost East, published in 1903. The book omits any detailed information about his visits to South Asia, Australia and New Zealand, and only briefly sketches his travels in Japan and Korea. The main focus is on Manchuria, Siberia (covering the Amur region and Buryat communities of Trans-Baikalia), and particularly on Sakhalin, which was the ultimate goal of his journey.

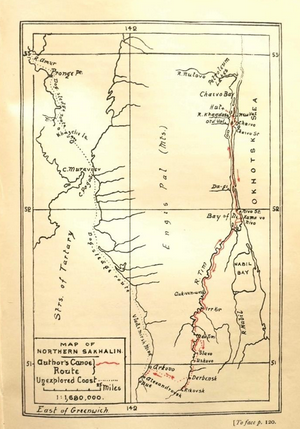

In Cambridge, Hawes had been exposed to the ideas of scholars of anthropology like W. H. R. Rivers and Alfred Cort Haddon, and developed an interest in physical anthropology which he was later to pursue in his own research projects in Crete, but in 1901 he was still an interested amateur rather than a professional ethnographer. One factor behind his fascination with Sakhalin was the phenomenon that has been described as ‘Ainu fever’24 – the upsurge of ethnographic interest in the Ainu, whose origins were regarded as a mystery, and were the subject of widespread, and often fanciful, speculation around the start of the twentieth century. Hawes hoped to visit the Ainu communities of Sakhalin, which he thought had been less exposed to outside influences than those of Hokkaido. But he arrived by boat in the island’s administrative centre, Aleksandrovsk – more than half way up the west coast of Sakhalin – only to discover that overland transport links to the Ainu communities in the southern part of the island were non-existent, and it would take him at least ten days to reach the nearest Ainu village25; so instead, he turned his attention to the Nivkh and Uilta villages which could be reached by making a seventy-five mile overland journey to the outpost of Derbensk (now called Tym’ovskoe), and then travelling northwards along the River Tym’ (which Hawes call the ‘Tim’) to Nyiskii Bay (‘the Bay of Ni’) on the Pacific coast, and to Chaivo Bay beyond. These two bays form a long thin chain running up the east coast of the island, separated from the open ocean only by narrow sand spits, beyond which the ‘dull roar’ of the sea was always audible.26 Hawes’ voyage down the river in Nivkh canoes began around 10 September 1901. and the return journey from Derbensk to the sea and back took about three weeks.

Map of Hawes journey across Sakhalin

(from In the Uttermost East, opposite p. 120)

He was accompanied for most of the journey by a Russian guide and interpreter named Alexander Lochvitzky, a political exile who (like a number of the better-educated inhabitants of the Sakhalin penal colony) worked in the colony’s meteorological service27, and by two Nivkh guides – cousins Vanka and Armunka28 – who (after lively negotiations about wages) piloted the canoes in which he travelled and introduced him to the communities along the way. Armunka came from the village of Yrkyr’, about half way down the River Tym’, and Vanka from another nearby village which Hawes calls ‘Kherivo’ (perhaps the village of Chkharvo).29 Vanka spoke relatively fluent Russian and became the source of much of Hawes information about Nivkh society and about other groups including the Uilta and ‘Tunguses’ (as Hawes terms the various Evenk, Ulcha and Nanai people who travelled frequently to Sakhalin from the Asian mainland). Hawes evidently enjoyed Vanka’s company, and describes his Nivkh guide as being ‘quite poetic at times; the life of the whole party’.30 Armunka, on the other hand, was more reserved and had greater difficulty communicating with Hawes and Lochvitzky, so it was not until the group stopped in Yrkyr’ on their return journey that Hawes discovered that Armunka was a senior figure from a relatively well-to-do Nivkh family. He was also renowned for his prowess as a hunter, and in the previous year had killed three bears, as well as capturing two bear-cubs who were being reared in the village for the bear ceremony, a crucial spiritual rite for all the Sakhalin indigenous groups.31 The role of Vanka and Armunka in the expedition illustrates the fact that by the early twentieth century, the indigenous people of Sakhalin had become essential providers of transport for colonizers and visitors: operating ferries and river transport, and providing winter postal services on dog sleighs, which remained by far the quickest means of transport during the months when the island was deep in snow.32

The interpreter Lochvitzky – a devout Christian who later escaped to the United States via Japan and became a US army officer – credited his encounter with Hawes for saving his life at a time when the Sakhalin penal system had driven him to despair: ‘I wanted to commit suicide, but before blowing my brains out, I fell on my knees and prayed, and our heavenly father heard my prayer and not only answered it but sent me immediate deliverance in the person of C. H. Hawes, professor of Trinity College, Cambridge, England, to whom I was appointed interpreter and body-guard.33

The journals which Hawes kept on his journey begin with detailed descriptions of the people and places he encountered on his arrival in Sakhalin, but become increasingly condensed. For much of his journey, they are written in note form: rapid jottings of Hawes own observations, sometimes mixed in with pieces of information from conversations he has been having with his guides and others. Here he is, for example, observing a Nivkh woman slicing and cooking salmon (with punctuation as in the original):

two slices each side after head taken off if big thrown away. Two knives, one ordinary size, pointed end = for cutting one very long tapering and very sharp for skinning. Dogs have white eyes, very often one white and one brown. Wipe fishy hands. Quietly staked fish etc. Cut willow slips, stripped leaves off and slit them, put slices of salmon between two cross-pieces of willow either side and bound end up with bit of stripped green bark then other end in ground and grilled fish.34

This is accompanied by a little sketch of the two knives used to skin and fillet the fish:

Sometimes, though, Hawes bursts out into passages of lyrical prose, as though lines that he wants to save up for use in his travel book have suddenly entered his head, like this description of the Uilta house in which he stayed in the village of Dagi on Nyiskii Bay: ‘Look at the glorious ceiling which stretches from floor to chimney! Was there ever panelled oak telling half so much of the story of those who had dwelt there. The poles and rich bark lining literally glowed with the polish of many thousand fish that smoked over that cheery fire.’35 And again, on the return journey up the Tym’:

Many years may I remember the sunlit evenings spent on the tranquil River Tim, far from the haunts of busy man, among the home of the bear and fox and with simple jolly Gilyaks, full of fun, always ready to laugh at a joke, making always the best of our position whether it were to camp on a pleasant sandy reach to a golden sunset, or to betake ourselves, soaked and with not a dry thing, to other grassy high banks, wet and dripping, to make our couch.36

These passages, with minor embellishments, appears almost verbatim in the published version of In the Uttermost East.37

When Hawes wrote up his travel journal in book form, he seems to have been torn between the desire to write a popular travelogue and his urge to present a scholarly account of his travels. He therefore interspersed his descriptions of the people and places he encountered with lengthy passages of historical, geographical or anthropological background. He was a product of his time, a believer in stage theories of human evolution who described the indigenous people he met as ‘weird-looking’38, ‘simple’39 and as ‘children of the forest’40, emphasising the gap between them and the ‘civilized world’.41

Like many other observers of the region’s indigenous people, he believed that they were doomed to extinction, though Hawes based this view less on belief in an inexorable process of natural selection than on a critique of Russian policies: ‘The chief causes of the dying out of the natives is disease, the narrowing limits of their hunting ground, the decay of the spirit of their race, and their inability to adapt themselves to another mode of living which is gradually but surely being forced upon them… If there were more friends of the Gilyaks like Mr. Pilsudski, who was a political exile on the island, they indeed might yet be saved from extinction… I fear, unaided and not followed up, his efforts have failed…’42 Hаwes particularly noted the impact of forest clearing and the lighting of fires by Russian colonizers, which had ‘driven off or destroyed wild game and restricted it to a smaller compass’43, and quoted Nivkh elders who told him that ‘before the Russians came there were plenty of bears, sables and reindeer, but since they arrived and burnt the woods the rich have become poor’.44

The desire to appeal to a wide audience meant that Hawes adopted the rather arch style of writing that was popular in travelogues of the day: a style that can grate on the ear of the twenty-first century reader. One narrative device which starts to appear in his travel diaries but is much more pronounced in his book, is the trick of using improbable analogies between indigenous people or practices and western counterparts to highlight the gulf between the Sakhalin indigenous village and the ‘civilized world’. The conversation with the Nivkh shaman (cham45) mentioned in the first section of this essay, for example, is jotted down in simple note form in the diary, but in Hawes’ book, the shaman’s question – now rendered as ‘how is it the Russians have come here, and why do they live in big villages and not in the forest’ – prompts the following comment from the author:

What a revelation of a totally different world was here! Surely a question suitable for the new economic Tripos at Cambridge. The complexity of our economic life, the interdependence of country on country – nay, hemisphere upon hemisphere – the vast network of communication in the civilized world on which it was based, how could I, in a few words, make this member of a primitive tribe understand?46

And the difficulties of communication with the shaman, which in Hawes’ diary are attributed to interjections by his interpreter, are now blamed squarely on the shaman himself: ‘I put many questions to the cham, but they were scarcely answered satisfactorily; either he was not as intelligent as we had hoped, or for fear of being laughed at, he was beating about the bush.’47

Yet Hawes’ writings also express great respect for the skills of his Nivkh guides and for the ‘softness of manners and politeness’48 and linguistic skills of the Uilta people with whom he stayed, and he demonstrates an awareness of how strange – even absurd – he himself must have appeared to the people in whose villages he arrived un-announced and without invitation: ‘we arrive with tremendous baggage, give a lot of trouble to have things dried.’49 He enjoyed sharing jokes with his hosts about moments of mutual mis-communication. At the Uilta village of Dagi on Nyiskii Bay, where he arrived with his ‘tremendous baggage’, for example, Hawes tried, through sign language, to ask his hosts to help him dry a shirt which had become sodden on the journey, but they, assuming that he wanted it washed, promptly plunged it into water – a mistake that prompted fits of laughter when it was understood. Days later, Hawes’ guides, who ‘dearly love a joke’50, were still retelling the story of the shirt.

Many of the observations of indigenous life that Hawes jotted in his diaries reappear in his published book, but some of the vivid detail disappears. Most notably, the context of Hawes’ travels in Sakhalin and his contacts with Russians on the island is somewhat hazy in the book, and become clearer only in light of the information contained in the diaries. To protect his Russian informants (many of whom were convicts or political exiles) Hawes generally omitted their names from In the Uttermost East, but the diaries reveal that his key contact in Sakhalin was Karl Khristoforich Landsberg (1853‒1909), a military officer who had been exiled to the island after murdering a money-lender and his servant. By the time Hawes arrived in Sakhalin, Landsberg had become famous for his engineering achievements, which had helped to open up the island’s transport network.51

Although Hawes did not meet the ethnographer Lev Shternberg (who had returned to St. Petersburg before Hawes arrived in Sakhalin), he did obtain access to some of Shternberg’s research notes, possibly via Landsberg, and transcribed sections of these into his diary.52 These include descriptions of archaeological finds which Shternberg interpreted as suggesting that Ainu had once lived in the north as well as the south of Sakhalin, and estimates of Nivkh birth and death rates in in the northern part of the island. Hawes’ diary jottings also give insights into the varied attitudes of Russian officials and settlers to the indigenous people. Often these were derogatory and dismissive – like the comments of a ‘Caucasian Cossack’ farmer who lived near the Tym, and who told Hawes that ‘the Gilyak are a dying out race and very lazy’53. Yet some of the Russian officials had at least taken the trouble to study indigenous languages, and one (the chief official of the Tymovsk region) provided Hawes with valuable vocabularies of Nivkh and Uilta language.54

When In the Uttermost East was published towards the end of 1903, Russia and Japan were on the brink of war, and most reviews of the book appeared after the Russo-Japanese War had broken out. This conflict, and the strongly pro-Japanese feelings which it evoked in the English-speaking world, coloured the reception of Hawes book. The New York Times’ review, for example, was entitled ‘Dread Sakhalin’, and used information from the book to emphasise the squalor of Far Eastern Russia and horrors of the Russian penal system. Hawes’ account of his time with the indigenous people is dispensed with in a fleeting reference to ‘the chapters about the Gilyaks, Tunguses and Trochons [sic], Indians who resemble in many respects the American aborgines of the Far Northwest’.55 A lengthy review of the book in the Sydney Morning Herald, meanwhile, barely mentioned Hawes’ account of Sakhalin (which takes up sixteen of the book’s twenty-three chapters) and instead focused on his descriptions of Buddhism in Buryatia, and on embellishing Hawes’ comments about Russo-Japanese rivalry in Korea.56

Yet Hawes’ travel writings also had an impact of which he himself was almost certainly unaware. When Japan gained control of the southern half of Sakhalin (which they called Karafuto), just four years after Hawes’ visit to the island, Japanese officials and educators suddenly became aware of the large lacunae in their knowledge of this new colony, and there was a brief boom in Japanese publications about the island. The works of Shternberg and Piłsudski were in Russian or Polish, and many had not yet been published57, so they were less easily accessible to Japanese readers, but Hawes’ newly published book could be read by most educated Japanese. One of the first Japanese studies of the colony of Karafuto to appear was Karafuto Jijō [Conditions in Karafuto], by educational journalist Aizawa Hiroshi, who begins by telling his readers that he has by chance just discovered the ‘most interesting report on the convicts and native people of Karafuto’.58 This report was Hawes’ In the Uttermost East, and a substantial part of Aizawa’s information about the indigenous people of Japan’s colony was taken directly from Hawes.

Everyday Life Between Empires

In 1901 the area of the Tym’ River where Hawes travelled was still predominantly inhabited by Uilta and Nivkh people. There were Russian convict settlements at Derbensk and Ado Tym’ on the upper reaches of the river, but Ado Tym’ was on the remotest fringe of the Russian settled area – an impoverished village to which, Hawes wrote, ‘the worst exiles were sent’.59 From there on, with the exception of a few nights spent with the oil prospectors on Nyiskii Bay, Hawes either camped by the river with his Nivkh guides – eating fish which they caught from the river and sharing the rice, tinned meat and Cadbury’s cocoa which he had brought with him60 – or slept in the houses of Nivkh or Uilta families. The villages where he stayed each had a Russian-appointed ‘headman’ (starosta in Russian), but were in effect still self-governing. Hawes learnt from his Nivkh informants that the communities around the mouth of the Tym’ did not seek the help of Russian police to keep order: they had ‘their own organizations’ and their own elders ‘to whom the injured apply for justice’.61 During his stops Hawes jotted down descriptions of his surroundings, at times (no doubt) misinterpreting the things he was seeing around him, and at others offering patronising comments about things such as dirt and smells. But in his diaries he is more interested in recording than in passing explicit judgements, and they therefore offer unusually vivid glimpses of everyday life in the houses where he stayed.

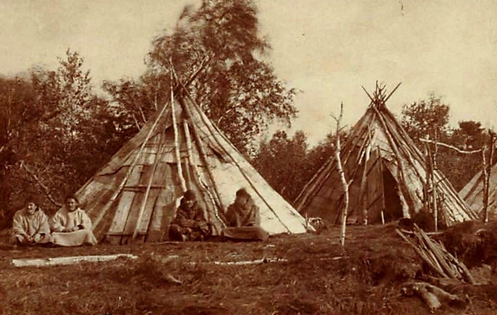

Uilta Village, early 20th century (photographer unknown)

Here is his description of the evening meal in a house in the Uilta village of Old Val, on Chaivo Bay:

View as one reclines on the plentiful supply of reindeer skins of many a strange face around the fire, some rending raw fish heads with teeth, others dipping smoked fish into birch baskets of seal oil and others sedately smoking. Children intervening remarks. Fish above and everywhere, as far as the eye can penetrate the recesses of the roof. The hostess is said to be the prettiest woman on Sakhalin and all men fall in love with her. Mothers and fathers especially are very fond of children.62

And first thing the following morning:

Women get up first (undress by undoing their trouser leggings, leaving on their long tunic – sole other garment) and throw round them a reindeer coat with sleeves. Children roll themselves naked in rugs and skins. Babies quieted by suckling as in China. Women early to well to get water in birch baskets. Fire lighted. Kettles on. Tea made, cured kita [salmon] served up in one dish and these torn with the teeth.63

Hawes seemed fascinated by the children, and observed them closely, as in this word-sketch of dinner in a Uilta house in the nearby village of Dagi: ‘The menu for supper was kita roe and rice mixed. We should call it caviar and rice served up in birch bark bowls. The tiny children found it difficult, with a cross between a chopstick and spoon, to get it into their mouths and the other hand was brought to bear to bundle it in’.64 Meanwhile, the men of the household were washing down their meals by ‘sipping tea from cups or saucers’65: compressed ‘brick tea’ was one of the most important items bought by Nivkh and Uilta villagers from Russians and other traders in exchange for fish and furs.66

The Starosta of Nivo and his wives with another Nivkh man

(from In the Uttermost East, opposite p. 272)

One or two nights later (the diary is hazy about dates67) Hawes was staying at the summer house68 of the starosta of the Nivkh village of Nivo, which gave him an opportunity to make comparisons between the layout of Uilta and Nivkh homes:

The hut was built of logs to a height of 4ft 6 inches rectangularly, then an obliquely sloping roof of pine poles for rafters and bark for tiles. Over the fire were two square holes cut in roof from central longitudinal pole to let out the smoke. From outside therefore the difference in shape strikes one at once, the Orochon [Uilta] are tent like, the roof beginning on the ground and the space enclosed is ellipsoid, while the Gilyak [Nivkh] roof rises from a rectangular wall of logs. Inside two differences strike one at once, the fire place is raised occupying the centre. It is like a box of 12 inches in depth full of earth and ashes. Around there is a long bench about 15 inches from the ground round 3 sides of hut and nearly 5 feet in depth. Here one sits and sleeps, some on skins but these are not so essential as with Orochons.69

Hawes, as we shall see, witnessed the ways that imperial rivalries were tearing indigenous society apart, but he also witnessed continuities from pre-colonial times that were still alive in Sakhalin at the start of the twentieth century. For centuries, the island’s indigenous communities had been woven into an extensive and multilingual trading route that extended southwards towards Japan and westwards towards the societies of the Lower Amur, Manchuria and China. One part of this network was sustained by the people whom the Sakhalin Nivkh called ‘Janta’ (sometimes also transcribed as ‘Santa’ or ‘Santan’) – traders who crossed to the island from the Lower Amur region, bringing Chinese brocades, metalware, glass beads and other goods, which were exchanged for Sakhalin furs. The Janta were mostly members of the Ulchi or Nanai language groups, though some were Amur Nivkh or Ainu.70 Brocade robes, imported from China along this trading route, became important status symbols in Ainu society: one of the earliest European references to Sakhalin, dating from the late 17th century, reports that Japanese sailors who had visited the island had seen native inhabitants wearing ‘fine Chinese silks’.71 During the middle years of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) some inhabitants of Sakhalin also travelled to the Asian mainland to trade or pay tribute to Qing officials at Deren, a settlement near the mouth of Lake Kizi on the Lower Amur.72

Trade between Sakhalin islanders and indigenous people from the lower Amur was still active at the beginning of the twentieth century, and Hawes, as he crossed Chaivo Bay at night on a Nivkh canoe, encountered a boat rowed by visitors from the mainland with their hair braided in distinctive long queues – a scene that almost exactly replicates 18th and early 19th century European and Japanese description of Janta canoes and their crews around the shores of Sakhalin.73 In summer, these traders from the Amur region brought clothing and other items which they sold at high prices to Sakhalin indigenous customers, in turn paying high prices for locally caught furs.74

The Russian colonization of Eastern Siberia and Sakhalin had disrupted connections between the island’s indigenous inhabitants and the Chinese Empire, but had created new transport links between Sakhalin and the mainland – particularly between Aleksandrovsk and the Russian settlement of Nikolayevsk at the mouth of the Amur. From about the 1850s onward, Nivkh traders from the mainland had begun to shift their patterns of trade with Sakhalin. Rather than buying goods from Manchu merchants to sell on the island, they traded on credit with Russian settlers, using the earnings from their sales of Russian goods to repay their debts.75 Russian steamers now made the crossing in the summer months, while in winter indigenous people both from Sakhalin and from the Asian mainland still crossed the frozen Tartar Straits on dog or reindeer sleighs. The Uilta family with whom Hawes stayed in Val was a relatively wealthy one, whose wealth (according to his Nivkh interpreter) was manifest in the fact that they ‘had more sledges [than others], and went more frequently in winter to Nikolaevsk to dispose of their greater quantity of reindeers, furs, etc.’76 In winter, he was told, ‘when fresh meat is very scarce, and at the end of several hundred miles’ journey, a reindeer is sold for twenty-five rubles [in Nikolaevsk]’.77 For the people of Sakhalin, Nikolaevsk was an important source of guns, clothing and other items: Vanka and Armunka, for example, wore Manchurian hats bought in the Siberian town’s markets.78

Meanwhile, Russian colonization was increasing the eastward flow of Siberian indigenous peoples from the mainland to Sakhalin, with mixed consequences for the Sakhalin Nivkh and Uilta. Earlier relations with the Janta had involved a mixture of peaceful trade and exploitation. Nivkh guide Vanka told Hawes that, as far as he remembered or had heard from others, relations between incomers from the mainland had been relatively peaceful: ‘In past times Vanka says when there were many Gilyaks and many Tunguses etc. they never fought over their hunting. The Tunguses came and put nets on Gilyak river, and the latter took them up and gave back but never fought’.79 But the wider processes of empire building had unleashed forces that were changing these dynamics. Land pressures encouraged larger reindeer herding groups such as the Sakha (Yakut) and Evenk groups to migrate eastward, and growing numbers were entering Sakhalin, some of them travelling to Nyiskii Bay to fish and hunt. Hawes learnt that these immigrants ‘live in better conditions than Gilyak. Hunt Sable with dogs or reindeer and each one catches 120 in a hunting season and sell prey in Nikolaevsk wholesale 5 r[ubles] each’.80

The growing presence of the merchants, hunters and herders from the mainland provoked new tensions between them and the Sakhalin indigenous villagers. Vanka informed Hawes that the Nivkh resented the new arrivals because ‘they are not hospitable, and do not give the Gilyaks food and drink when they call.’81 Similar problems were also noted by Bronislaw Piłsudski, who wrote that the Nivkh and Uilta living along the Tym’ had reached an unwritten agreement with Evenk reindeer herders that the latter would only hunt on the left bank of the river near the coast, leaving other areas to their original inhabitants, but that the Evenk ‘did not respect the agreement, often crossed the river to forbidden territory, took sables from traps that were not theirs, and even killed domesticated reindeer belonging to the Orochons [Uilta]’.82

‘Tungus’ from the mainland with their reindeer in Aleksandrovsk;

photograph collected by Charles Henry Hawes in Sakhalin

(original possibly by Ivan Nikolaevich Krasnov)

(Library of Congress, control no. 2018684030)

The relationship was not always hostile, though. Uilta spoke a language closely related to those of the incomers from the mainland, and were in any case (as Hawes noted more than once) adept linguists: ‘they speak Tunguse [sic], Ainu and Gilyak, as well as own [language]’, and conversations between Hawes’ Nivkh guides and his Uilta hosts were generally conducted in the Nivkh language.83 The reindeer which the Evenk brought to Sakhalin were different from those traditionally reared by the Uilta: smaller and paler in colour – sometimes grey or white, unlike the dark brown animals kept by the Uilta. These pale reindeer were prized by Uilta, who used their skins to decorate clothes and other household items, and Uilta herders encouraged the interbreeding of local reindeer with the introduced Evenk reindeer stock.84 Piłsudski’s writings commented on the way that the physique of the Uilta reindeer was changed over time as a result of this interbreeding, and Hawes too noted that the herd of reindeer belonging to the relatively prosperous Uilta family with whom he stayed in Chaivo were ‘of a grey-buff colour, and occasionally all white’.85

Increased contact with the Evenk may have had other more surprising consequences too. Piłsudski argued that it was the Christianized Evenk who had been responsible for converting the Uilta to Russian Orthodox Christianity, and it was certainly true that, by the early twentieth century, most Uilta had adopted at least some aspects of the Orthodox faith (while fewer of their Ainu and Nivkh neighbours were Christian).86 Henry Hawes also commented on the symbols of Christianity that he encountered in the Uilta villages that he visited, although he attributed these to the activities of Russian priests, about whom he had some unflattering comments to make. In the village of Dagi, for example, Hawes noticed that many of the Uilta inhabitants

wear crosses given by priests. Priest comes in winter to central place like Ado Tim and word is sent to the starostas of tribes. Some come and receive the Communion or the burial or other services are read for them or over them whenever they are dead. But the sermon is not liked because for every rite the priest takes sable or other skins and makes, report has it, some 300 rubles.87

At New Val (across the bay from Old Val) too, he observed that ‘children and women wear crosses like charms and rosaries’. The villagers there told him that ‘once a year priest comes (no devotions otherwise) and performs rite. He brings spirits and trades them.’88 In the house where he stayed in New Val, Hawes was startled to find the floor covered not only with a ‘big rug of fish skins’ but also with ‘two pieces of rich brocaded silk (Chinese)’, apparently brought to the village to be altar cloths for a church that a priest had promised to build four years ago, but which had never materialised.89 He was told that the priest who had made this promise had ‘collected 489 rubles for the building of the church, but, so far, they had nothing but a handbell’, and added ‘I believe Sakhalin has been rid of the presence of this pope, whose true mission, by all accounts, appeared to have been to gather sable-skins’.90

The Impact of Shifting Frontiers

The burdens of colonialism on the indigenous people were intensified by the shifting border, which made it necessary for them repeatedly to readjust to the changing imperial order. During the period before 1875, when Japan had joint sovereignty over Sakhalin, Japanese merchants and fishing enterprises had made inroads into the island, and Ainu, Nivkh and Uilta islanders had become accustomed to buying Japanese goods such as rice and other preserved foodstuffs, which supplemented their supplies during the long harsh winter. At the time of the 1875 Exchange Treaty, Japan, while relinquishing political control over Sakhalin, retained extensive fishing rights. Despite efforts by the Russian authorities to curtail the expansion of Japanese fishing, by the first years of the twentieth century thirty Japanese entrepreneurs were operating a total of almost one hundred fisheries along the coasts of Sakhalin91, and thousands of Japanese fishermen spent the summer months working there, while others came to the island as traders or to work for Russian fishing ventures.92 In the southern part of Sakhalin some prominent Ainu figures also obtained large fishing leases which they operated in cooperation with Japanese fishery interests: the most famous example being the Ainu elder Bahunke from the village of Ai, whose niece, Chuhsamma, married Bronislaw Piłsudski in 1903.93 In many of the fisheries indigenous people were employed in highly exploitative conditions, but the presence of the Japanese fishing enterprises (and of the storehouses that they left under the management of local people when they departed to Japan during the winter) encouraged an expanding trade in Japanese goods. On Niyskii Bay, Hawes found Japanese schooners which had travelled to the mouth of the Tym’ ‘to barter rice, kettles and cauldrons, rifles, earrings etc. for furs, and to fish and salt salmon during the spawning season.’94

Japanese Fishing Vessels in the Siska Gulf on the Eastern Shore of Sakhalin, c. 1890

(photograph probably taken by Innokentii Ignat’evich Pavlovskii)

(Library of Congress, control no. 2018691413)

But, as tensions between Japan and Russia intensified in the lead-up to all-out war, these connections became harder to sustain. Hawes’ shorthand notes of his conversation with the Nivkh shaman and others on the shores of the Bay of Chaivo records the following exchange: ‘Why poverty? One reason, the Japs used to come in ships and bring flour, rice, tea etc. and so the Gilyak could exchange fish. Since the Russians took the island the Japs frightened away and so the Gilyaks starve on the bay.’95 Reduced competition from Japanese merchants strengthened the bargaining power of their Russian competitors, who sold goods to the indigenous people from colonial outposts like Derbensk and Ado Tym’. The Uilta and Nivkh of the Tym’ area accumulated debts to these merchants which they then had to pay off by catching more fish or trapping more animals for furs. On his return journey up the Tym’, Hawes found one village empty of male inhabitants because all the men had gone fishing and fish drying ‘to pay their debts up the river. They go to pay at villages and at Ado Tym’ for flour and potatoes etc., paid in fish.’96

The greatest devastation, though, came from loss of hunting and grounds to the colonizers and from epidemic diseases introduced to the region by incomers from Russia and Japan. Bronislaw Piłsudski noted that the annual arrival of Japanese fishing and trading ships at the mouth of the Tym’ brought smallpox to the region, and he and another Sakhalin-based doctor had attempted a vaccination campaign amongst the Nivkh in the late 1890s, but with little success.97 Meanwhile, influenza was taking a terrible toll. On his way back from his journey down the Tym’, Henry Hawes met the Russian overseer at Derbensk, who gave him a stark description of an influenza epidemic of March 1898, when the local indigenous people had been found ‘dying in every hut and said they were starving. He on own account opened government stores and gave away [food] but they had cold “grippe” and died’.98 Another major epidemic of influenza was to sweep through the indigenous communities of Sakhalin during the Russo-Japanese War, when the disruption to trade between Japan and Sakhalin added to the miseries of indigenous groups who relied on Japanese rice and other produce for survival. In March 1905, Bronislaw Piłsudski, visiting the Ainu villages of the Taraika region (south of the Tym’) wrote, ‘along my entire route I encountered sick people; there were also persons dying. All of them were starving’. His estimate was that a quarter of the region’s indigenous population was killed by the epidemic.99

Even at the time of Hawes’ visit to the island, three years before the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, fear of Japan was intense, and Hawes recorded that ‘twice during my stay telegrams were received stating that war had been declared between Russia and Japan’.100 The mood of fear stirred Russian feelings of mistrust towards the indigenous people of the island – particularly towards Sakhalin Ainu, who had long-standing links to Hokkaido Ainu communities and to Japan more generally.101 After the island was divided in 1905, those who found themselves under Japanese rule on the southern side of the line no longer had ready access to the trade links to the Amur region which, as Hawes had seen, were so crucial to everyday life102, and eventually, by the 1930s, even cross-border links within the island itself were almost severed. So Nivkh and Uilta families who had relatives living on both sides of the imperial frontier became divided.103 Just as declining trade with Japan disrupted indigenous life at the start of the twentieth century, a decade later life for those in southern Sakhalin would be disrupted by the loss of trade links with Russia, and the Christianized Uilta would find themselves pressured to replace their reverence for God and Tsar with reverence for the Japanese Emperor.104

Demarcating the Russo-Japanese Border in Sakhalin/Karafuto, 1906

(as depicted in a 1932 painting by Japanese artist Yasuda Minoru)

The indigenous people, though, were not just passive victims of this colonial exploitation, and Hawes’ diaries also offer glimpses of the resilience and adaptability that were to enable them to survive the ravages of twentieth century division and war. His trading interactions with Sakhalin indigenous villagers involved energetic and shrewd bargaining on both sides105, and his conversations (like those with the shaman, quoted earlier) were two-way exchanges of knowledge: his informants seemed as eager to gain information from him as he was to learn about their customs and beliefs. His guide Vanka not only spoke Russian but also took advantage of the trip to learn some English, repeatedly asking Hawes to teach the English words for ‘bear, fish, sun, moon etc.’106 When Vanka was paid for his work at the end of the voyage, he surprised Hawes by carefully dividing his earnings between separate purses which he kept in order to allocate and keep track of his personal budget.107 Vanka’s work for Hawes had a well-planned purpose: the Nivkh guide was saving up to marry and to build or buy a house in Ado Tym’108, though we do not know whether he succeeded or whether he was one of those who fell victim to the 1905 ‘flu pandemic and the other disasters that were to beset his community in the first half of the twentieth century.

Destructions and Survivals

Almost exactly one hundred years after Hawes returned to Aleksandrovsk at the end of his journey to Chaivo Bay and back, I was standing on the shores of the River Tym’, watching Nivkh fishermen cast their nets into its tea-coloured water. Hawes himself never returned to Sakhalin after his departure for the Siberian mainland on 27 October 1901.109 Back in England, he developed a growing interest in Cretan archaeology and anthropology, and on his way to Crete for a study trip in 1905, he met the pioneering American archaeologist Harriet Boyd, whom he married in 1906. The couple settled in the US, where Henry gave the first courses in anthropology to be offered at the University of Wisconsin-Madison110, and later became Associate Director of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. He died in Boston 1943.111

Meanwhile, the world Hawes had glimpsed on the Tym’ in 1901 had been transformed by the vast and unpredictable forces of global politics. I arrived at the village of Chir-Unvd, close to Armunka’s home village of Yrkyr’, by a very different route from that taken by Henry Hawes a century earlier. With a multinational group of Russian, Japanese and Western European scholars, I had taken the overnight train from the city of Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk in the south of the island to Tym’ovskoe (which in Hawes’ day was the convict outpost of Derbensk), and from there we had travelled by bus along a rough and rutted road through the little town of Ado-Tym’ and through forests of birch and larch to Chir-Unvd. Later, as we headed towards Aleksandrovsk, the bus would stop briefly so that we could get off to pay our silent respects to a wooden Orthodox cross – implanted in the embankment and devoid of inscription. It commemorated the victims of ‘the Repression’ (as it is usually called): the Soviet Era purges of Sakhalin islanders.

Indigenous people figured prominently in the Repression. During the Second World War, Uilta and Nivkh people on both sides of the border that divided Russian from Japanese territory were recruited by the colonial rulers as spies, in the belief that their special knowledge of the local terrain would make them particularly effective in collecting information about the enemy. As a result, after the Soviet Union seized control of southern Sakhalin in 1945, many Uilta and Nivkh men from the southern part of the island were rounded up by the Soviet authorities as ‘collaborators with the enemy’ and were sent to labour camps, from which only a small number returned. Some of the survivors and their families, as well as almost all of the Sakhalin Ainu population, subsequently moved to Japan, where their descendants still live today.112 On the northern side of the border, meanwhile, Uilta and Nivkh were organized into collective fishing and reindeer herding units during the 1930s. One of these was located in the village of Val, where Hawes had stayed.113 Chir-Unvd itself was created through the forced merger of a number of the Nivkh settlements which had once extended along the banks of the Tym’.114 Although the new collectives preserved elements of indigenous culture, their creation during the 1930s was accompanied by a vigorous campaign to stamp out indigenous ‘superstition’ – identified particularly with shamanism. This ‘struggle against shamanism’, together with wider suspicion about the indigenous people’s historical links to Japan, resulted in many indigenous elders and others becoming victims of Stalin’s purges.115

By 2001, when we visited Chir-Unvd, collectivization had given way to new forces of capitalist market competition and multinational-driven resource development, which were presenting their own challenges to Sakhalin’s indigenous people. As one of the Nivkh fishermen whom we met by the Tym’ put it, in the past people worked together, but now with capitalism everyone was just out to look after themselves. But, he added, at least most of the young people in this predominantly Nivkh village were finding work locally – on farms or in fishing and forestry – rather than migrating to the cities in search of employment.

The dense forests through which Hawes passed as he travelled by canoe down this stretch of the river have been thinned by burning and clearing, transforming the landscape to a mixture of pasture and silver-birch forest. Chir-Unvd consists of small Russian style wooden houses, many with rows of fish hanging up to dry outside in the traditional Nivkh manner, and is one of three communities in Sakhalin which boasts a school providing education in the Nivkh language.116 As we stood on the bank of the Tym’ in the early evening light, one of the fishermen hauled in a fish, a woman from the village deftly sliced it in the precise way that Hawes had observed a century earlier. A fine singer, she had recently returned from New York, where she had been to perform with a Nivkh musical ensemble. As a new millennial generation of Nivkh and Uilta has recovered and passed on the complex story of their region to the world, the long-neglected modern history of Northeast Asia’s indigenous people has come into sharper focus. And in this on-going process of recovering the past, the glimpses offered by Charles Henry Hawes, for all their limitations, add pieces to a historical jigsaw puzzle that was for so long dispersed and obscured by the grand power struggles of nations and empires.

Nivkh Fishermen on the River Tym’, Chir-Unvd, October 2001

(©Tessa Morris-Suzuki)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS – With thanks to Dr. Tatyana Roon and her colleagues from the Sakhalin Regional Museum, who organized the 2001 visit to the Tym’, and to Alice Baldock and Judy Brown for their help in locating Charles Henry Hawes’ diaries, letters and photographs in the Bodleian Library. My thanks also goes to Professor Bruce Grant for his very helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Notes

Transcribed version of Charles Henry Hawes’ Diaries (account of travels in Sakhalin, hereafter CHHD-S) held in the manuscript collection of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS. Eng. misc. c. 1040, pp. 111.

The presence or absence of reindeer herding is often seen as a defining distinction between Nivkh and Uilta communities, but as Heonik Kwon observes, at least by the second half of the twentieth century some Nivkh communities also kept reindeers; see Heonik Kwon, Maps and Actions: Nomadic and Sedentary Space in a Siberian Reindeer Farm, University of Cambridge PhD Thesis, 1993, pp. 5‒6.

CHHD-S, pp. 111‒112; see also Charles Henry Hawes, In the Uttermost East, London, Harper and Brothers, 1903, pp. 232‒234.

‘I do not know how far in what follows the interpreter (Mr. Clay) imparted his own ideas into the questions put, and therefore in answers’, CHHD-S, p. 112.

See Lev Shternberg (ed. Bruce Grant), The Social Organization of the Gilyak, New York and Seattle, American Museum of Natural History / University of Washington Press, 1999; Bronislaw Piłsudski, ed. Alfred F. Majewicz, The Collected Works of Bronislaw Piłsudski, 4 volumes, (hereafter: Collected Works), Berlin and New York, Mouton de Gruyter, 1998.

On the museum and Piłsudski’s role in its development, see M. M. Prokof’ev, N. A. Samarin and V. V. Shcheglov, Sakhalinskii Muzei 120 Let: Ot Otkrytiya do nashikh Dnei (1896‒2016 gg.), Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, Sakhalinshkii Oblastnoi Kraevedcheskii Muzei, 2016, pp. 10‒21.

CHHD-S, p. 157. In the diary Hawes refers to Endyn as ‘Imdin?’ and Piłsudski as ‘Pilsordsky’, but he corrects the spelling of Piłsudski’s name in his published book. On Emdyn, see also ‘Researcher and Friend of the Sakhalin Natives: The Scholarly Profile of Bronislaw Piłsudski’, in Piłsudski, Collected Works, vol. 1, p. 26.

See letter from Bronislaw Piłsudski to Charles Henry Hawes, 12 September 1902, held in Bodleian Library.

This photograph appears in a collection of photos entitled Vidy Ostrovo Sakhalina (Views of the Island of Sakhalin) produced by the Sakhalin Museum around the beginning of the twentieth century. A copy of this is available online in the collection of the Library of Congress, accessed 15 June 2020). Most of the photos in that collection are by Ivan Nikolaevich Krasnov.

See, for example, Yamamoto Yūkō, Karafuto Genshi Minzoku no Seikatsu, Tokyo, Arusu, 1943; Yamamoto Yūkō, Karafuto Ainu no Jūkyo, Tokyo, Sagami Shobō, 1943 (Yamamoto’s given name is also sometimes romanized as ‘Sukehiro’); Ishida Eiichrō, ‘Hōryō Minami Karafuto Orokko no Shizoku ni tsuite – 1’, in Ishida Eiichirō Zenshū, vol. 5, Tokyo, Chikuma Shobō, 1970, pp. 333–75.

See Roger Sanjek, ‘The Ethnographic Present’, Man, vol.26, no. 4, pp. 609-628, quotation from p. 613.

Good examples of this are B. Douglas Howard’s Life with Trans-Siberian Savages, London, Longmans, Green and Co, 1893, and Harry de Windt’s The New Siberia, London, Chapman and Hall, 1896, particularly pp. 112‒117. Hawes notes in his diary that (according to Landsberg) de Windt spent only one day on Sakhalin, and (in Hawes’ words), wrote a lot of ‘trash about the island’, see CHHD-S, p. 97. Howard’s account is even more disturbing. In one particularly repellent passage he describes stealing a look at the naked body of an elderly hospitalized Ainu woman, which he proceeds to describe in utterly dehumanizing terms, by pretending to be a doctor; see Life with Trans-Siberian Savages, p. 8. Less egregious but similarly exoticized images appeared in Japanese guidebooks and travel accounts like Hishinuma Uichi’s Karafuto Annai Chimei no Tabi, Tokyo, Chūō Jōhōsha, 1938.

See Bronislaw Piłsudski, ‘B. O. Piłsudski’s Report on his Expedition to the Ainu and Oroks of the Island of Sakhalin in the Years 1903‒1905, in Collected Works, pp. 192‒221.

See, for example, Richard Zgusta, The Peoples of Northeast Asia Through Time: Precolonial Ethnic and Cultural Processes Along the Coast Between Hokkaido and the Bering Strait, Leiden and Boston, Brill, 2015, pp. 80‒84.

The earliest written references to the Uilta appear to come from a report by Japanese official Takahashi Moriaki, who visited the island in 1715, and from information collected by French Jesuit scholar Jean-Baptiste du Halde from missionaries who visited the Lower Amur region in the last decade of the 17th century. See J B du Halde, Description Géographique, Historique, Chronologique, Politique et Physique de l’Empire de Chine et de la Tartarie Chinoise, vol. 4, The Hague, Henri Scheurleer, 1736, p. 15; Koichi Inoue, ‘Uilta and their Reindeer Herding’, in Murasaki Kyoko ed., Ethnic Minorities in Sakhalin, Yokohama, Yokohama Kokuritsu Daigaku Kyōiku Gakubu, 1993, pp. 105‒127, particularly p. 108; Tat’yana Roon, Uyl’ta Sakhalina: Istoriko-Ethnograficheskoe Issledovanie Traditsionnovo Khozyaistva I Material’noi Kul’tury XVIII ‒ Serediny XX Vekov, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, Sakhalinskoe Oblastnoe Knizhnoe Izdatel’stvo, 1996, p. 7.

For example, Leopold von Schrenck, Reisen und Forschungen in Amur-Lände in den Jahren 1854‒1856, vol. 3, St. Petersburg, Commissionäre der Köningliche Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1858; Lev Yakovlevich Shternberg, Gilyaki, Orochi, Gol’dy, Negidal’tsy, Ainy, Tokyo: Nauka Reprint, 1991; Shternberg, Social Organization of the Gilyak; Nakanome Akira, Karafuto no Hanashi, Tokyo, Sanseidō, 1917; Nagane Sukehachi, Karafuto Dojin no Seikatsu, Tokyo, Kōyōsha, 1925; Ishida Eiichrō, ‘Hōryō Minami Karafuto Orokko no Shizoku ni tsuite – 1’, in Ishida Eiichirō Zenshū, vol. 5, Tokyo, Chikuma Shobō, 1970, pp. 333–75. For other general anthropological works on the indigenous people of Sakhalin see also Kawamura Hideya, ‘Senjū Minzoku Orokko, Giriyāku no Seikatsu to Fūzoku, Karafuto Chōhō, no. 6, 1937, pp. 155‒165; M. G. Levin and L. P. Potapov, The Peoples of Siberia, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1964; Chuner M Taksami, Nivkhi: Sovremenoe Khozyastvo, Kul’tura i Byt, Leningrad, Nauka, 1967; E. A. Kreinovich, Nivkhgy, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, Sakhalinskoe Knizhnoe Izdatel’stvo, 2001 (originally published in 1973); Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, Illness and Healing among the Sakhalin Ainu, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1981.

See, for example Bronislaw Piłsudski, ‘Wants and Needs of the Sakhalin Nivhgu’, in Piłsudski, Collected Works, vol. 1, pp. 105‒136; Piłsudski, ‘B. O. Piłsudski’s Report on his Expedition to the Ainu and Oroks’; Bronislaw Piłsudski, ‘Selected Information on Individual Ainu Settlements on the Island of Sakhalin’, in Piłsudski, Collected Works, pp. 311–130; Bronislaw Piłsudski, ‘Statistical Data on Sakhalin Ainu for the Year 1904’, in Piłsudski, Collected Works, vol. 1, pp. 331‒345.

See, for example, Tanaka Ryō and D. Gendānu, Gendānu: Aru Hoppō Shōsū Minzoku no Dorama, Tokyo, Gendaishi Shuppankai, 1978; Karafuto Ainu Shi Kenkyūkai, ed., Tsuishikari no Ishibumi, Sappor,: Hokkaidō Shuppan Kikaku Sentā, 1992; Fujimura Hisakazu and Wakatsuki Jun eds., Henke to Ahachi: Kikikaki Karafuto de no Kurashi, soshite Hikiage, Sapporo: Sapporo Terebi Kabushiki Kaisha, 1994; Nikolai Vishinevskii, Otasu: Etno-Policheshie Ocherki, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, Dal’nevostochnoe Knizhnoe Izdatel’stvo, 1994; Kwon, Maps and Actions; Bruce Grant, In the Soviet House of Culture: A Century of Perestroikas, Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press, 1995; Roon, Uyl’ta Sakhalina; Hokkaidō Dōritsu Hoppō Minzoku Hakubutsukan, Karafuto 1905–45 – Nihonryō Jidai no Shōsū Minzoku, Abashiri: Hokkaidō Dōritsu Hoppō Minzoku Hakubutsukan, 1997; Tangiku Itsuji, ‘Aru Nibufujin no Senzen to Sengo’, Wakō Daigaku Gendai Jinbun Gakubu Kiyō, 4, March 2011, pp. 129‒143; Inoue Koichi, ‘A Case Study on Identity Issues with Regard to Enchiws (Sakhalin Ainu)’, Journal of the Centre for Northern Humanities, 9, March 2016, pp. 75‒87.

Mary Allsebrook (ed. Annie Allsebrook), Born to Rebel: The Life of Harriet Boyd Hawes, Oxford, Oxbow Books, 1992, p. 126.

See Christina M. Spiker, ‘“Civilized” Men and “Superstitious” Women: Visualizing the Hokkaido Ainu in Isabella Bird’s Unbeaten Track in Japan, 1880’, in Kristen L. Chiem and Lara C. W. Blanchard, Gender, Continuity and the Shaping of Modernity in the Arts of East Asia, 16th‒20th Centuries, Leiden and Boston, Brill, 2017, pp. 287‒316, see particularly p. 292.

CHHD-S, p. 96; Hawes, In the Uttermost East, pp. 80 and 82. In his published book, Hawes calls his interpreter ‘Mr. X’, but in his diaries he names him as ‘Mr. Lochvitsky’. Here I use the romanization of his name which Lochvitzky himself used after moving to the US.

‘Vanka’ is a Russian diminutive of Ivan. Hawes does not give Vanka’s Nivkh name, and is uncertain whether he has recorded Armunka’s name correctly, see Hawes, In the Uttermost East, p. 156.

See, for example, A. V. Smolyak, Etnicheskie Prosessy u Narodov Nizhnevo Amura i Sakhalina, Moscow, Nauka, 1975, p. 174; Piłsudski, ‘Selected Information on Individual Ainu Settlements’, p. 312.

‘Exiled Russian in the Pulpit’, The Journal and Tribune (Knoxville, Tennessee), 28 June 1909, p. 4.

CHHD-S, p. 107. In the transcription, the word ‘panelled’ has been rendered as ‘paralleled’, but this is clearly a mistake. Hawes uses the word ‘panelled’ in this passage when it appears in his book.

‘Cham’ is a transcription of the Nivkh word for shaman. Hawes suggests that there is a difference between cham, whose role was primarily judicial, and the more religious ‘shaman of the Orotskis, the Golds and the Tungus on the mainland’, but this is not a difference recognised by other scholars of Nivkh culture. See Hawes, In the Uttermost East, p. 234‒235. On the role of shamans in Nivkh society, see for example Kreinovich, Nivkhgu, pp. 455‒471.

In his book, Hawes calls Landsberg ‘Mr. Y’. See CHHD-S, pp. 74‒75; Hawes, In the Uttermost East, pp. 79‒81; On Landsberg, see also Vlas Doroshevich (trans. Andrew A. Gentes), Russia’s Penal Colony in the Far East: A Translation of Vlas Doroshevich’s ‘Sakhalin’, London and New York, Anthem Press, 2011, Part 2, Chapter 7.

‘Dread Sakhalin: “In the Uttermost East”, a Timely Travel Book, by Charles H. Hawes’, New York Times, 11 June 1904.

Just one of Piłsudski’s essays, his survey of Karafuto Ainu villages (translated and edited by Ueda Susumi) was published in Japanese in 1906; see ‘Karafuto Ainu no Jōtai: Rokoku Pirusudosukī Shi Kikō’, parts 1 and 2, Sekai, no 26, 1906, pp. 57‒66 and no. 27, 1906, pp. 42‒49 (NB This journal Sekai, published by Kyōka Nippōsha from 1904-1917, is distinct from the more famous post-war Japanese journal of the same name).

Hawes notes that the going rate of exchange established by one Manchurian merchant from Nikolaevsk was three bricks of tea for one sealskin, CHHD-S, p. 140. Hawes himself carried tea as a trade item, and in Yrkyr’ paid 20 kopeks and half a brick of tea for a dog skin, CHHD-S, p. 118.

The problem is compounded by the fact that Hawes sometimes uses ‘old style’ dates (according to the Julian calendar, which was still used in Russia at that time) and sometimes uses ‘new style’ Gregorian calendar dates.

Nivkh people moved annually back and forth between two houses – a wooden chalet like summer house (ke ryf) and a semi-underground winter house (tulf tyv); see for example Lydia Black, ‘The Nivkh (Gilyak) of Sakhalin and the Lower Amur’, Artic Anthropology, vol. 10, no. 1, 1973, pp. 1‒110, particularly pp. 6 ‒16.

See Tezuka Kaoru, ‘Amūru-gawa Shimoryūiki to sono Shūhen no Hitobito’, in Hokkaidō Kaitaku Kinenkan ed., Santan Kōeki to Ezo Nishiki, Sapporo, Hokkaidō Kaitaku Kinenkan, 1996, pp. 5-9.

This information comes from a report sent to Nicolaes Witsen, a Dutch scholar, statesman and avid collector of geographical knowledge, who included it in his 1705 magnum opus on Siberia and East Asia – see Nicolaes Witsen, Noord en Oost Tartarye, ofte Bondig Ontwerp van eenige dier Landen en Volken welke Voormaels Bekent zijn Geweest, Amsterdam, François Halma, 1705, p. 63.

Shiro Sasaki, ‘A History of the Far East Indigenous Peoples’ Transborder Activities between the Russian and Chinese Empires’, Senri Ethnological Studies, vol. 92, pp. 161-193, 2016 (see particularly pp. 168-170); Mamiya Rinzō, Tōdatsu Kikō, Dairen: Minami Manshū Tetsudō Kabushiki Kaisha, 1938 (Original written in 1810 and first published in 1911).

On Bahunke [also written Bafunke or Bohunka], see Uchiyama and Akashi, Saharintō Senryō Keieiron, p. 40; ‘Researcher and Friend of the Sakhalin Natives’, pp. 27‒28; Bronislaw Piłsudski, ‘An Outline of the Economic Life of the Ainu on Sakhalin’, in Piłsudski, Collected Works, vol. 1, pp. 271‒295, particularly p. 292; Sentoku Tarōji, Karafuto Ainu Sōwa, Tokyo, Shikōdō Ichikawa Shoten, 1929, pp. 6 and 50‒51.

See, for example, Piłsudski, ‘B. O. Piłsudski’s Report on his Expedition to the Ainu and Oroks’, pp. 199 and 213.

‘Offers a Course in Anthropology: Subject Never Has Been Taught at Wisconsin’, Iowa County Democrat, 17 October 1907, p. 4.

‘Offers a Course in Anthropology: Subject Never Has Been Taught at Wisconsin’, Iowa County Democrat, 17 October 1907, p. 4.

‘Offers a Course in Anthropology: Subject Never Has Been Taught at Wisconsin’, Iowa County Democrat, 17 October 1907, p. 4.

See Bruce Grant, ‘Afterword: Afterlives and Afterworlds: Nivkhi on the Social Organization of the Gilyak, 1995’, in Shternberg (ed. Grant), Social Organization of the Gilyak, pp. 187 and 224; Grant, In the Soviet House of Culture, p. 90.

A good example of the campaign against shamanism is the short story ‘In the Valley of the Tym’’, by Sakhalin novelist Semyon Bytovoi, published in 1957. Bytovoi’s hero, the communist pioneer Matirnyi, persuades the Nivkh of the Tym’ valley to form a collective, but his efforts to encourage potato growing are sabotaged by the local shaman, who accuses Matirnyi of digging up the ground in order to steal it from the Nivkh people. When Matirnyi tells the local villagers that the potatoes they plant will be multiplied many-fold, the shaman promptly unearths the newly-planted potatoes to demonstrate that there are still the same number as were originally put into the ground. It is only gradually and through great hardship that (in Bytovoi’s tale) the Soviet hero is able to wean the indigenous community away from its “naîve” dependence on tradition; Semyon Bytovoi, ‘V Doline Tym’i’ in Semyon Bytovoi, Sady u Okeana, Leningrad, Sovietskii Pisatel’, 1957, pp. 3-45; for further information on the effects of the purges, see for example Grant, In the Soviet House of Culture, pp. 93‒108; Yuri Slezkine, Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small Peoples of the North, Ithaca and London, Cornell University Press, 1994, pp. 226‒229.

The other two are in Nogliki and Nekrasova; Tjeerd de Graaf and Hidetoshi Shiraishi, ‘Documentation and Revitalisation of Two Endangered Languages in East Asia: Nivkh and Ainu’, in Erich Kasten and Tjeerd de Graaf ed., Sustaining Indigenous Knowledge: Learning Tools and Community Initiatives for Preserving Endangered Languages and Local Cultural Heritage, Noderstedt, SEC Publications / Kulturstiftung Siberiens, 2013, pp. 49‒63, see particularly, p. 59.