Abstract: J. Robert Oppenheimer, scientific director of the Manhattan Project, became one of the most famous and influential public figures in the world following the emergence of the revolutionary new weapon, the atomic bomb, which was dropped over two Japanese cities in August 1945. Soon, however, he would be harassed by a Hollywood studio for permission to portray him in a big budget movie, and shadowed by the FBI because of his links to former Communists.

For much of 1946, both the MGM movie studio and the Federal Bureau of Investigation were closely monitoring three of the world famous scientists whose work had helped lead to the creation of the first atomic bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki seventy-five years ago this month.

MGM was producing a drama, titled The Beginning or the End, inspired by the pleas of atomic scientists. They demanded that Hollywood make a major movie urging the U.S. to turn away from building more powerful weapons, which would likely spark a nuclear arms race with the Russians and imperil the entire world. Soon, MGM would launch a big-budget project, with studio chief Louis B. Mayer calling it the “most important” movie he would ever produce.

In the year that followed, however, the original message of the MGM movie would shift almost 180 degrees in the opposite direction, ending as little more than pro-bomb propaganda. Why? Both President Harry S. Truman (who had given the order to bomb Hiroshima) and General Leslie R. Groves (director of the Manhattan Project) were given script approval rights, and they ordered dozens of cuts and revisions. Truman even mandated a costly re-take, and got the actor playing him fired.

Groves and Oppenheimer (right)

To even get that far, MGM had to convince the key people in the bomb project to sign releases granting permission to be portrayed in the film. This led to desperate attempts over many months to get Albert Einstein, Leo Szilard and the scientific director of the project at Los Alamos, J. Robert Oppenheimer, to approve their portrayal, while promising them (unlike Groves) no fee.

Einstein, now leading a public campaign for international control of the atom and convinced there had been no need to use the bomb against Japan, was so hostile to the idea of dropping the bomb that he penned a dismissive letter to MGM’s conservative studio boss Mayer. “Although I am not much of a moviegoer, I do know from the tenor of earlier films that have come out of your studio that you will understand my reasons,” Einstein wrote. “I find that the whole film is written too much from the point of view of the Army and the Army leader of the project, whose influence was not always in the direction which one would desire from the point of view of humanity.”

Mayer replied that he “was most anxious to have the picture made,” adding, “As American citizens we are bound to respect the viewpoint of our government….It must be realized that dramatic truth is just as compelling a requirement to us as veritable truth is to a scientist.” Einstein, understandably, still balked.

After weeks of pressure, however, Einstein and Szilard, beaten down, finally succumbed, even while believing the movie’s script was poor. However, the ever-conflicted Oppenheimer, the so-called “Father of the Atomic Bomb,” resisted.

While this was transpiring, the FBI was also chasing the three men, with a quite different motive.

J. Edgar Hoover suspected each of them of being a security risk, even sympathetic with the Soviet Union, due to their general leftwing views and association with liberal groups. So, in 1946, agents monitored Einstein’s mail and phone calls in Princeton, New Jersey. Agents tracked his writings, speeches, and broadcasts as well as his role with political and scientific groups, sometimes via informants who attended meetings. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover was known to have called Einstein an “extreme radical.”

Agents tailed Szilard in the street–leading to some amusing chases and capers–and also opened his mail, as General Groves sought to bar him from current and future national security programs. An Army colonel at the War Department asked J. Edgar Hoover to open a full probe of Szilard, as “he has constantly associated with known ‘liberals’…and has been outspoken in his support of the internationalization of the atomic energy program.”

One of the many reports from agents in his FBI file for 1946 admitted that the scientist was “well aware that he has been watched closely inasmuch as the post office inadvertently advised SZILARD and [Enrico] FERMI that General GROVES had ordered all their mail to be opened.”

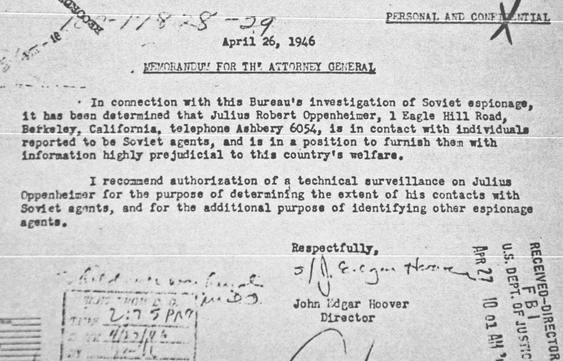

Agents followed Oppenheimer locally and on his many cross country trips–and tapped the phone at his Berkeley home. In obtaining approval for the phone tap, Hoover had cited the need to determine “the extent of his contact with Soviet agents, and for the additional purpose of identifying other espionage agents.”

J. Edgar Hoove Memorandum on Oppenheimer to the Attorney General

“Oppie,” as he was known to friends, was of course, especially vulnerable as his wife and brother (and his late mistress) had all been members of the Communist Party, as were several of his current or former associates. Yet for all their searching and harassing, the agents could not find evidence of his disloyalty. Still, the Oppenheimer probe would eventually lead to the hearings several years later that led to the loss of his vital security clearance.

The following excerpt from my new book The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood–and America–Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb finds the producer of the MGM movie visiting Oppenheimer at his home in April, 1946, to finally nail down his permission to be portrayed in the movie. Oppenheimer’s response would be recorded by the FBI, with a transcript, which appears here, revealed for the first time in the book.

***

On April 18, 1946, Sam Marx sent Oppenheimer a copy of the screenplay for The Beginning or the End, with the hope he would “glance through it” before they met three days hence in Berkeley. That Saturday night Marx arrived at Oppenheimer’s rambling one-story villa, high up on Eagle Hill with an expansive view of three canyons, the bay, and sunsets over the Golden Gate.

After dinner, Oppie spoke about the script, with his usual frankness. In a letter to his friend J.J. Nickson he would recount much of this discussion:

Oppenheimer: “Some of the themes in the movie are sound, but most of the supposedly real characters like Bohr and Fermi and myself are stiff and idiotic. When Fermi hears of fission he says my what a thrill and my most characteristic phrase was gentlemen, gentlemen, let us be calm….Most of the trouble rests in ignorance and bad writing, rather than in anything malign.”

Oppenheimer would tell Nickson that he found his visitor from Hollywood “sympathetic.” Marx seemed “honestly eager to get the script improved,” but even after the revisions, Oppie predicted “It won’t be very good.” At least in the current story, he added, the scientists seemed to be treated as “ordinary decent guys, that they worried like hell about the bomb, that it presents a major issue of good and evil to the people of the world.” He concluded: “I hope I did right. I think the movie is a lot better for my intercession, but it is not a beautiful movie, or a wise and deep one. I think it did not lie in my power to make it so.”

He seemed uncharacteristically insecure, however. “Let me hear from you,” he said to Nickson, “particularly if you think I did wrong or want me to try again.” He had other things to worry about. The FBI had started tapping the phone in his Berkeley home and recording the conversations.

***

When Sam Marx returned to Hollywood he immediately began revising the script. Fawning over his new friend, Marx assured him in a letter that he had impressed on the film’s writer “that the character of J. Robert Oppenheimer must be an extremely pleasant one with a love of mankind, humility and a pretty fair knack of cooking.”

He closed: “We are as eager for the truth as you are. . . . I would rather see you pleased with this picture than anyone else who has been concerned with the making of the atom bomb.” Marx may well have been sincere about that, but it never hurt to appeal to Oppenheimer’s vanity.

Two weeks later, near the end of a lengthy phone conversation—taped as usual by the FBI—Kitty Oppenheimer informed her husband, who was in the east, that he had received a letter from a “Hugh Cronin” (as the name was recorded in the transcript), “explaining why he would like to be you.”

Oppie asked: “Bill Cronin?” Kitty: “Hugh Cronin—that bloke that belongs to MGM.” This was Hume Cronyn, who had agreed to portray Oppenheimer in the movie.

“Well, I’ll tell you what I did on this,” Oppenheimer replied, then referred to General Groves’ top aide. “This very ugly creature, [Colonel W.A.] Consodine, called me and said that Marx had said it was all right and would I sign the release, and I said sure. I got the release and I signed it with a paragraph written in saying that all of this is subject to my receipt of a statement from Mr. Sam Marx that he believes the changes that have been made are satisfactory.” Possibly to re-assure his wife, he pointed out that their friend David Hawkins was still at the studio checking on things for him.

Kitty: “Oh.”

Robert: “Well, I didn’t think there was anything else to do. I don’t want anything from them and if I can work on his conscience, that is the best angle I have. It just isn’t worth anything otherwise, darling.”

At this juncture, the call faded in and out. “The FBI must have just hung up,” Robert quipped.

The transcript recorded Kitty’s response as: Giggles.

Then Robert concluded: “The only thing we can do there is to try to persuade them to do a decent job.”

***

The Beginning or the End movie poster

The movie would flop when released the following February. Oppenheimer declined to attend the premiere in Washington and even a screening closer to Berkeley. The Beginning or the End would fade from importance, but FBI surveillance of Oppenheimer would continue off and on for years.

The drawn, grey, haunted visage of J. Robert Oppenheimer in his later years came to symbolize a true expression of the atomic age and the decision to make and then use a revolutionary new weapon against two cities. His face appeared mask-like, but as always it was impossible to tell what was behind the mask, what was hidden or most deeply felt.

The investigations of his security lapses, begun even before Trinity, came to fruition as the Red Scare mounted in America and top-level resentment of Oppenheimer’s lukewarm reaction to developing the hydrogen bomb festered. It’s a long, complicated story, so the bare outline will have to suffice here. His security clearance (which Leslie Groves once stuck out his neck for) was finally revoked in 1953, a decision sustained after a contentious hearing the following year. During that process, the FBI once again listened in on his calls, this time featuring regular chats with his attorneys.

Oppenheimer was likely doomed when he admitted that he had lied a decade earlier about an approach to him by his friend Haakon Chevalier to find out if he might pass secrets to the Soviets. While he had refused that offer, he had behaved like “an idiot,” he admitted, in misleading the FBI about it. Among those who testified against him at the hearings were Leslie Groves, Edward Teller and E.O. Lawrence.

Stripped of the clearance, he managed to stay active lecturing and writing but the heart seemed to go out of him. He did not join the nuclear control efforts of Einstein and others, though he was by no means hostile to them. His views on making and using the bomb against Japan remained maddeningly inconsistent when they weren’t impossible to decipher (which is probably what he preferred). He said, “There is no doubt we were hideously uncomfortable about being associated with such slaughter,” yet later declared, “About the making of the bomb and Trinity, I have no remorse.” He confessed that physicists had “known sin” but also “I understand why it happened and appreciate with what nobility those men with whom I’d worked so closely made their decision.” Even his opposition to the hydrogen bomb–or “the Super”as it was called–was far from clear and forthright.

Shortly before his death he told The New York Times, “I never regretted, and do not regret now, having done my part of the job….I also think that it was a damn good thing that the bomb was developed, that it was recognized as something important and new, and that it would have an effect on the course of history.”

Urged by Oppenheimer’s friends, and Edward Teller, to signal some measure of rehabilitation, John F. Kennedy in 1963 awarded Oppenheimer the Enrico Fermi Award, which came with a $50,000 check. It was presented to him after the president was assassinated (his widow Jackie went out of her way to attend and asked to meet him). He died four years later, at the age of sixty-two, after a long bout with throat cancer.