Introduction

In “Okinawa Demands Democracy” Maedomari Hiromari patiently details the cruel political and economic injustices that burden Okinawans today, such as their pseudo-citizenship and semi-colonial status, a status that arose from the U.S. military occupation of Okinawa (which began with the horrific 1945 Battle of Okinawa). His analysis reveals the way that such injustices are an inevitable result of Tokyo’s subservience to Japan’s imperial masters in Washington, and it demonstrates that, as a result of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, none of the people of the Archipelago, in fact, enjoy full sovereignty. That same government that repeatedly plundered Okinawa during the past three quarters of a century under the banner of fighting for freedom and democracy has also repeatedly violated Japan’s sovereignty.

“Okinawa Demands Democracy” was published in the September 2018 issue of the political magazine Sekai (“World”), just a few weeks before Okinawans elected Denny Tamaki as Governor of Okinawa Prefecture. Okinawan opponents of the new Henoko base construction at Camp Schwab saw Governor Tamaki as an ally and/or representative who would respect the will of the people. Building on that success, of putting him in office, such base opponents have subsequently maintained their campaign and achieved other notable victories. For example, although the turnout was not spectacular, at roughly half the registered voters, 72.2 percent of the Okinawans who participated in the citizen-initiated referendum in February 2019 voted against the plan to relocate U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to Henoko. They then achieved success in the by-election of April 2019 when Yara Tomohiro, the candidate backed by Governor Tamaki, won, and also in the July 2019 election when Takara Tetsumi won a seat in the Upper House.

Undaunted by the accidental fire that burned down much of Shuri Castle in October 2019, by infections from SARS-CoV-2 early this year, by the sharp decline in February in the number of tour groups coming from overseas, or by U.S. military personnel accidentally spilling 227,100 liters of fire-extinguishing foam into residential neighborhoods on April 10 without apologizing, agents of peace in Okinawa have continued to work on peace education and to engage in non-violent direct resistance. Only the SARS-CoV-2 declaration of a state of emergency was capable of putting a damper on the flame of Okinawan peace building. And just recently, on June 7, Henoko base construction opponents retained their majority in the Okinawa prefectural assembly election. Maedomari’s “Okinawa Demands Democracy” gives us new awareness of the obstacles to peace and democracy, and the extent to which the Okinawans’ overcoming of those obstacles may result in greater security for people there, as well as for millions of people in East Asia.

What have the Japanese government’s economic promotion measures for Okinawa yielded?

The Okinawan economy faces a wide range of problems, including a high unemployment rate, a high turnover rate, a high rate of business closures, long working hours, low wages, low income, low savings, a low employment rate, a low rate of job offers, a low rate of home ownership, and a high economic polarization of society.

Okinawa has the lowest proportion of secondary industries (manufacturing), which tend to pay higher wages and provide better job security, whereas it has the nation’s highest rate of dependency on the service industry, which is an industry with low yearly incomes. There are not many decent jobs for people who want to work. Even if one finds a job, the wages are low. Moreover, Okinawan workers rank first or second in terms of long working hours. Pay raises are tiny. And many workers change jobs due to anxiety about their future. The jobs-to-applicants ratio exceeds one, meaning there are more jobs than job seekers, but fewer applicants actually find jobs that they want and are satisfied with, and only 60% of workers gain full-time employment. With 44.5% of the work force (i.e., 300,000 people) composed of non-regular employees, their working conditions are harsh. (This is compared to a 38.2% national average in 2012). The ratio of people who start their own business is fourth in Japan, but Okinawa comes in third place when it comes to business bankruptcy and closure rates. We see a repetitive cycle of job losses, job departures, job changes, and re-employment. This cycle hampers pay raises and creates an unstable employment environment. Okinawan workers are out of breath.

As to those who commit themselves to the challenge of finding work outside Okinawa Prefecture, they need to have a university degree if they want to get a position at a good company in Tokyo. While the national average for advancement to university is more than half at 55%, Okinawa’s rate is 39%, the lowest in Japan. (The rate of advancement to high school is also the lowest in Japan). Even when Okinawan students manage to be awarded a scholarship and advance to university, it is not unusual for their scholarship to wind up being used for family household expenses, with the result that they cannot pay their tuition and must withdraw from the university. Even if they are able to get a job, many say, “I have a low salary, few holidays, constant overtime, and am physically exhausted.” 26% quit within one year of being hired. 48.5%, or roughly half, quit within 3 years of being hired. And in the harsh job market, the chances of finding a job again are slim. Many of those who seek to acquire computer skills do not have a computer at home. Only 850 households out of every 1,000 has a personal computer in Okinawa (compared to a national average of 1,339 computers for every thousand households). This is the lowest distribution of computers in any region of Japan.

The number of people who visit Okinawa has been increasing rapidly from year to year. In 2017 this number reached 9,580,000. For the last three years, there has been a double digit increase in the number of visitors. The number of foreign tourists has exceeded more than 2 million. On International Street (Kokusai Dōri), there is never a day without Chinese, Koreans, Taiwanese, or people from Hong Kong. The number of times that cruise ships make port calls has also been increasing, and with 3,000 or 5,000 people per cruise ship coming to Okinawa, there are not enough taxis and buses. It has been revealed that due to the shortage of taxis, many unlicensed taxi drivers are giving illegal rides to tourists. The total income from tourism has increased from 32.4 billion yen at the time that Okinawa was returned to Japan (1972), to 670 billion yen (in 2017), which is an increase of twenty-fold. The tourist economy gets a lot of attention now since it is a key industry that is triple the size of the military base economy.

And yet, 23,000 people are breathing hard, with an annual income from that tourist industry that is less than 1 million yen. Earning more than 4 million yen per year is beyond their wildest dreams. That is the reality that they face. What in the world happens to the one-trillion-yen economic ripple effect of income from tourism that Okinawa Prefecture boasts about?!1 The industry is in a difficult spot, one in which the hotel occupancy rate has stagnated due to the “lack of help,” in which positions cannot be filled for lack of applicants.

So many problems in the Okinawan economy have piled up that people’s hearts are close to breaking. Nevertheless, these problems also symbolize the dream and the possibilities of the Okinawan economy.

Okinawa Prefecture attempts to lure companies by describing their weaknesses as strengths. For example, regarding the high unemployment rate, they say Okinawa is “the easiest place in Japan to hire workers.” The low wages are the “magnet that attracts companies.” The high turnover rate is a reflection of the “fluidity of the work force.” The frequent opening and closing of businesses represents the “healthy appetite for starting businesses.” The low percentage of workers with high educational attainments shows that there is “potential demand and room for growth in the field of education and human resource businesses.”

The Okinawan economy, which used to be dependent on the U.S. military bases, has been transformed into one that takes advantage of returned bases to create new centers for business, commerce, and tourism. Further return of U.S. military bases will provide potential demand for large-scale public works projects, and Okinawa will leap from the military-oriented “Keystone of the Pacific” to the “business hub of East Asia” and the “international distribution hub of East Asia.” The upcoming Asia international distribution hub-ization of Naha Airport by All Nippon Airways will set a precedent for such a direction.

These 160 islands that make up Okinawa prefecture are rich with bountiful nature and each has its own distinctive character. They are gaining attention as bases for sightseeing, health, and medical tourism. The warm climate is attracting émigrés from aging societies as a place for their last home, or so-called “resort ending.”

Okinawa is gaining attention in the fields of health, environment, finance, transportation, research, education, sightseeing, bases, and trade. It is a place overflowing with people (including people from afar, young people, and “crazy people”), things, money, and information. With these rich possibilities in mind, there is an urgent need to formulate a far-sighted economic development vision and a master plan—10 years, 30 years, or 100 years down the road.

With Okinawa in such a situation, the conflict between the Abe administration and the administration of Okinawa Governor Onaga [Takeshi, 1950-2018] over the U.S. military bases is having great repercussions.

Democracy challenged

“Is this country really a democratic state?”

“Is this country really a sovereign state?”

The citizens of Japan must once again, now, ask these questions. Of course, the citizens of Okinawa Prefecture must also ask these questions.

Why, for so many years and to such an extent, have the problems of the U.S. military bases in Okinawa been left unsolved and unattended to? Is it that the politics of this country are immature? Are our state bureaucrats incompetent? Are our politicians ignorant and unenlightened? Is it because the mass media is not functioning and craves lazy slumber among people who lack knowledge and vision, and who do not care about others?

In Okinawa there is a problem. It is called the “Okinawa problem,” but it is really the “Japan problem.” Many questions and doubts, anxieties and distrust, discontent and indignation, injustice and unfairness, inequality, and wrath swirl around this problem.

Is Futenma really the most dangerous base in the world? 2 Is moving the Futenma base to Henoko really the only way to remove the danger of Futenma?3 How much does it cost to move it to Henoko? Why is Japan covering those expenses instead of the U.S. military? What is the new base at Henoko supposed to protect, and from what must the new base protect it? Why is the will of the people of Okinawa ignored after their wishes have been made clear by elections? In the midst of planetary-scale global warming, why are [U.S. and Japanese government officials] going off the deep end in a mad dash to destroy the precious coral reef that absorbs carbon dioxide, and why is construction of the base their first priority? When and where is the ability of the U.S. Marine Forces to deter enemies going to be exhibited? How many soldiers in the Marines are stationed in Okinawa in the first place? Why are residents on main islands in Japan so comfortable with twisting the arms of Okinawans to put these bases in Okinawa? Why are Japanese police being mobilized as guards so that an American military base can be constructed?

If Japan were a democratic state, one would expect that the results of elections, i.e., the will of the people, would be respected and the results would lead to an improvement in the situation. Why is the will of Okinawans viewed so lightly and why must it be run over roughshod despite the fact that it was repeatedly made plain for all to see in many past mayoral, municipal, prefectural, gubernatorial, and national elections? This complete disregard for the will of the people after an election has, time after time, resulted in Okinawans feeling discontented, dissatisfied, distrusting of elections, and fed up with politics.

If the will of the people is demonstrated through an election, and yet the results of that election are ignored and rejected, then it is time to admit that ours is in no sense a democratic state. A country in which the minority is dominated by the majority, in which the tyranny of the many over the few is permitted, is nothing other than a tyranny.

A government that oppresses and suppresses the voices and the screams of the disadvantaged through the power and violence of the police, the Coast Guard Stations, and the Self-Defense Forces (SDF), and does not take seriously the sovereignty of localities or local self-government is no different from pre-War Japan and the heavy-handed fascist state of those days.

All of this is now happening in Okinawa. And yet, the mass media have lost sight of the art of fully communicating to the public even the facts, let alone the truth, as they remain ever attuned to the interests of the powerful by broadcasting all day long the scandals of celebrities and politicians, and as they are compelled to compete against each other in jumping to the beat of information manipulation by the powerful.

A government that is not “accountable” to the people

One ability is clearly lacking among [civil servants working for] the government of this country, i.e., the politicians and the administration, and those who execute its policies, i.e., the bureaucrats: accountability, which is the “responsibility to explain.” The Kōjien Dictionary defines “accountability” as “the social obligation on the part of companies and the government to explain their various activities to the public and to stakeholders. The responsibility to explain.”4

The question I raised at the beginning of this article is a question I have consistently raised for the last 20 years, ever since the problem of Futenma arose. Recently, too, I was invited to speak at public hearings and I was summoned before the Diet as a witness at meetings such as at the House of Representatives Budget Committee regional public hearing in 2017, the House of Councillors Budget Committee in March 2018, and the House of Councillors Special Committee on the Problems of Okinawa and the Northern Territories in June 2018. As I was answering their questions, I hurled questions back at them.

But at Diet committee meetings, I distributed questions to the Diet members in the form of reference materials at the outset as if these were test problems: an “examination on the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty.” I asked them to answer the questions.5 Of course, not one of them did.

For example, where on earth does the following claim come from? “The Futenma Base is the most dangerous base in the world.” Whenever something happens, this expression is repeated by Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide, the person who fulfills the role of adviser to Prime Minister Abe Shinzō’s cabinet.

Even only counting the number of accidents during the 45 years ending in 2017, after the so-called “return to the Main Islands” in 1972 when administrative authority over Okinawa was transferred to Japan, there were 738 accidents involving U.S. military aircraft in Okinawa. [See note for citation in Japanese].6 Looking at the number of incidents that have occurred at each of the bases, only 17 of those were at the Futenma Air Base—10 accidents involving military helicopters and 7 accidents involving fighter planes. But at Kadena Air Base, there have been 8 accidents involving helicopters and 500 involving fighter planes, for a total of 508 accidents. Kadena has actually had 30 times more accidents than Futenma. Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga emphasizes that they will eliminate the danger by moving Futenma with its 17 accidents to Henoko, but he has never discussed eliminating Kadena Air Force accidents and relocating that base somewhere else.

Why is that? The reason is clear. It’s because “Kadena is off limits.”7 And the solution to the problem lies beyond the wall of difficult negotiations with the U.S. government. If he touched on that problem, there is no question that the Abe administration would fall apart.

From the well-known “Miyamori Elementary School Jet Crash” of 1959 in which 17 people were killed, including 11 children, after the crash of a fighter jet with its fuel tank filled to capacity, to the 1968 Kadena Air Base B-52 crash involving a giant bomber with a full bomb load, the root cause of many tragedies has been Kadena Air Base.8

Nevertheless, in the case of fighter planes, they do reach their destination at the base. (Out of 607 accidents, 500 happened inside the base). But in the case of military helicopters, there are many accidents outside the base, in which the helicopter is not able to reach its destination. Moreover, they cause many fatal accidents. During the 45 years since the return of Okinawa (in 1972), 33 out of 131 helicopter accidents occurred on the base, and the remaining 98 accidents outside the base. Of these outside-base accidents, 30 were on vacant land or similar locations, 16 were in the vicinity of residences, 14 on private airfields, 14 on farms, and 14 on the sea. In the case of the remaining 10, where they occurred is “unknown.”

At Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, mainly helicopters are deployed. Based on what I have seen of the helicopter accident reports, [I think that one can conclude that] 75% of the accidents in which the helicopter took off from Futenma occurred outside the base. In other words, it is not Futenma base that is dangerous but the U.S. military helicopters that take off from it that are dangerous. There is scant evidence that the “only way to eliminate the danger of Futenma is to relocate it to Henoko,” as Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide claims. This is because even if Futenma is relocated to Henoko, the U.S. military helicopters that take off from Henoko will continue their training at helipads at 60 or more places that have been set up throughout Okinawa. If Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide wants to “eliminate the danger,” the only way to do that is, in fact, to prohibit U.S. military helicopter training in residential areas and to discontinue the flying of U.S. military aircraft.

About the Henoko U.S. military base construction, Prime Minister Abe Shinzō says, “I want to carefully explain it to those of you who are residents of Okinawa Prefecture and gain your understanding.” He says this at every turn, but Prime Minister Abe himself has neither explained it carefully to the residents nor has he made any effort to gain our understanding. In the case of the Moritomo Gakuen scandal and the Kake Gakuen scandal too, Prime Minister Abe’s account of what happened and his “careful explanation” have left many people feeling it was insufficient and incomprehensible.

In this country there is an unwritten rule that whenever a problem cannot be solved it should be postponed, and that if it still cannot be solved after the postponement, we should pretend that it never happened. The Moritomo Gakuen and the Kake Gakuen scandals that rocked the Diet are a typical example of this phenomenon. The core question of whether Prime Minister Abe was involved or not was postponed, and in the end, people treat the issue as if there had never been an issue.

The heavy-handed politics of “military dispatches and discrimination”

As to why the new base construction at Henoko is necessary, Japanese politicians and administrations are never accountable to the citizens of Okinawa Prefecture and Japan.

Consider the case of the Abe cabinet. There is a cabinet that does not fulfill its responsibility to explain. Concerning the new base construction at Henoko, they have strangely clung to their original position and used brute force, invoking the power of the state to deal with citizens who object to it. By pouring out vast amounts of public funds for unknown purposes, they force on us absurd base construction projects.

The Abe administration’s style of ramming through unpopular U.S. base construction policies stands out, even compared to previous postwar Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) administrations. His style is symbolized by the fact that, in 2007 during his first administration, he dispatched a Maritime Self-defense Forces minesweeper tender against the movement opposing the new base construction at Henoko, and in 2014, during his second administration, he browbeat and attacked the movement by considering another deployment of a Maritime Self-defense Forces minesweeper tender to Henoko. Against the Abe-style statement “consistent with our ocean patrolling activities, use anything that you have at your disposal,” Ishiba Shigeru, who was the Minister of Defense during the first Abe cabinet, in fact warned Abe by saying, “We should be very cautious about dispatching the Maritime Self-defense Forces.”

Back in 2007, the Administrative Vice Defense Minister was Moriya Takemasa. I was then the vice-chair of the editorial committee for a local newspaper in Okinawa. Attempting to learn about the background of this deployment of a Maritime Self-defense Forces minesweeper tender, I telephoned Vice-Minister Moriya.

“Mr. Moriya, we have reached a historical turning point. By deploying a minesweeper tender equipped with cannons in Henoko where everyone there is an unarmed citizen, this is the first time for the Self-Defense Forces to turn their cannons on citizens of Japan. During your era, you are going to etch this deed into history.” Vice-Minister Moriya explained, “I asked the Coast Guard to provide security, but there was strong resistance from the citizens, so if I had forced security to [go there], some people might have drowned, and my request for security was turned down. [The Coast Guard] said, ‘If you want to go that far, then use the Self-Defense Forces,’ whereupon we looked into the possibility of dispatching to Henoko a minesweeper tender as a security base.”

The deployment of a minesweeper tender—was that Vice-Minister Moriya’s idea or decision, or was it Prime Minister Abe’s idea or decision? This is unclear. But it is an undeniable fact that Prime Minister Abe gave a positive response in the Diet to the “dispatch” (hahei) of a minesweeper tender to Okinawa.

For some reason Prime Minister Abe is, in a heavy-handed way, challenging Okinawa to a duel. The residents merely wish to show their opposition to the construction of military bases, but Abe is physically coercing the residents by dispatching soldiers of the Self-defense Forces, sending riot police reinforcements, and tightening security.9 And that is not all.

“Starvation tactics” through budget cuts

In the 2014 election for the governor of Okinawa, Prime Minister Abe ostentatiously carried out a cut in the Okinawa-related government budget. This was when incumbent Governor Nakaima Hirokazu was backed by the ruling LDP party and the New Komeito Party but was defeated by Onaga Takeshi (who had been the mayor of Naha City) and when Onaga opposed the new base construction in Henoko with his “All Okinawa” campaign that aimed for an “economy that does not depend on the bases” (datsu kichi keizai).10 As if choking Okinawa with velvet gloves, Abe cracked his whip and cut the government’s budget little by little, and attacked Governor Onaga’s administration by way of starvation tactics.

For many years there has been a strange trend in which the [central] government’s Okinawa-related budget increased just as anti-base governors emerged (Yara Chōbyō, Taira Kōichi, and Ōta Masahide), and decreased when pro-base governors emerged (Nishime Junji, Inamine Keiichi, and Nakaima Hirokazu). This is a strange trend indeed.

The trend has been particularly pronounced after budget revisions. The Ōta Masahide Prefectural Administration opposed the forced use of bases and rolled out a struggle in the courts that went all the way to the supreme court. But the budget was greatly increased with a budget revision, and the Ōta administration enjoyed the largest recorded budget, at 470 billion yen.

In response to base opposition the government increases the budget, and in response to acceptance of the bases the government decreases the budget. This strange phenomenon is proof that this country’s government is incapable of providing any kind of logical explanation to Okinawans about why U.S. military bases in Japan are necessary. “If the majority of the citizens of Japan feel that the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty is necessary, then the government should fairly distribute the burden of the U.S. bases to the rest of Japan.” Such were the words of Governor Onaga Takeshi, who even once served as the LDP Okinawa Prefecture Federation Chief Secretary. But none of the governors in this country have raised their hand to volunteer their region to substitute for Futenma as base site.

Even if people approve of the U.S. military bases and view them as a “deterrent,” they do not want to host the U.S. military in their own region. The burden of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty is forced on Okinawa, while the benefits of it are shared with everyone in the country. In response to the claim that “Okinawa receives economic stimulation measures in exchange for its hosting the bases,” Governor Onaga once caustically retorted, “If you want to go to such lengths, then let’s be prepared to follow this to its logical conclusion. We’ll pass on the economic stimulation measures, and you can have the bases.”

There is no end to the suffering from U.S. military bases. There have been many accidents caused by emergency landings, such as in December 2016 when a U.S. Marine Corps Osprey had to make a crash landing in the northern part of Okinawa’s Main Island, and was seriously damaged;11 and in [October] 2017 when a CH-53E heavy-lift transport helicopter had an emergency crash landing and went up in flames also in the northern part of the Main Island.12 And there were many other emergency landing incidents on other islands. A part from a helicopter landed on the roof of a nursery school in the vicinity of the Futenma Air Base, and six days later [in December 2017], right in the midst of the uproar, another serious accident happened in which a window fell from an in-flight CH-53 helicopter onto the playground of an elementary school.13

There have been many incidents involving U.S. soldiers, such as the (2016) rape and murder of a 20-year-old woman by a man who was a civilian employee of the U.S. military who had originally been a soldier in the Marines.14 The number of incidents caused by U.S. soldiers during just the 45 years from 1972 when administrative authority of Okinawa was transferred to Japan until 2017 is 5,967. Among them, 580, or roughly 10% of the total, have been murder, mugging, rape, and arson, i.e., “felonies.”15 While there are on average 130 cases in Okinawa per year in which someone is victimized in an incident in which the perpetrator is a U.S. soldier, the government gets its way with abusive language such as, “Bear it, since you are the recipient of economic stimulation measures.”

During the last 10 to 20 years, traffic accidents caused by people affiliated with the U.S. military have been on the increase. Compared to earlier years when 40 accidents or so occurred, we see a major increase, to between 130 to 200 accidents per year.

|

The number of victims of sexual violence within the U.S. military is on the rise these days. (See Figure 2). Concerning crimes by U.S. soldiers that occur in Okinawa, it is pointed out that the “proportion of crimes is lower than the proportion of crimes committed by Okinawan residents,” but here they are talking about the incidence of crimes that occur outside the base, and reports on the number of incidents inside the U.S. military bases are not published. One could view the crimes occurring outside of the bases as the overflow of crimes from inside the bases. When it comes to regions that are burdened with U.S. military bases, one must always pay attention to the crime statistics of the Department of Defense.

According to the statistics of the Veteran’s Administration, only about 25% of sexual assaults are recognized. Thus it is clear that three out of four women victims have not reported the sexual violence to the authorities. The rape and murder that was committed in 2016 by the former U.S. Marine represents only the tip of the iceberg, in terms of reflecting the increase in sexual assaults on U.S. military bases.

What in the world are the U.S. military in Japan and the U.S. military in Okinawa protecting, and what are they protecting it from? For the residents of Okinawa Prefecture, greater than any emergency military threat is the threat of U.S. military crimes in times of peace and the threat of being hurt by U.S. military exercises.

The Abe administration pushing Okinawa in the direction of “base dependency”

One of the policies that the Onaga Prefectural Administration worked on building, that would allow the people of Okinawa to extricate themselves from the suffering caused by U.S. military crimes and U.S. military exercises, was a “post-base economy.” It was said in the past that Okinawa Prefecture had an “economy that relies on the 3Ks.” The “3Ks” were kichi (bases), kōkyō jigyō (public works projects), and kankō keizai (tourism related). Back in 1965, as much as 30.4% of the gross income of Okinawa Prefecture was made up of base-related income, but this had dropped to 15.5% by 1972 when Okinawa was “returned to Japan proper.” By 2014 the level of dependence on base-related income had dropped further, to one third what it was in 1972, down to 5.7%.

The tourist economy meanwhile dramatically increased in scale from approximately 440,000 tourists entering Okinawa Prefecture before the return (to Japan) to 9,500,000 in recent years. Partly as a consequence of the income from tourism and the boost from the increase in foreign tourists, there was a 20-fold increase in tourism income from 32.4 billion yen in 1972 to approximately 670 billion yen in 2017.

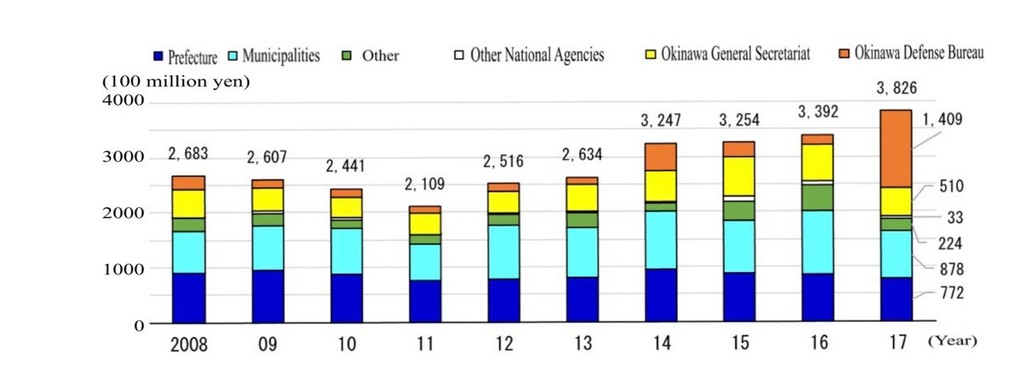

The Abe Administration shook up the Onaga Prefectural Administration even as the Onaga Administration aimed to shift away from the military base economy toward the vitality of a privatized economy. According to documents from the Okinawa Prefecture Contractors Association, which depends heavily on public works, after Governor Onaga took up his post, expenses for public works commissioned by the “Okinawa General Office of the Cabinet Office,” i.e., expenses for general public works, dropped drastically. Instead, expenses for public works from the Okinawa Defense Bureau greatly increased, and expenses for defense-related projects surpassed those of general public projects for the first time (See Figure 3).

|

Looking at materials in “The State of the Construction Industry” (Kensetsu gyō no genkyō) that the Okinawa Prefecture Contractors Association distributed during the six years from 2010 to 2015, the 2013-fiscal-year Cabinet Office budget rapidly increased from 26.9 billion yen to 53 billion yen; there was a decrease of 22.5 billion yen during the 2014 fiscal year; and it was nearly cut in half to 30.5 billion yen. In the 2015 fiscal year there was a further decrease of 6.3 billion yen (i.e., to 24.2 billion yen). On the other hand, between the fiscal year 2013 and 2014, the fiscal budget of the Okinawa Defense Bureau doubled (to 31.6 billion), and in the end, actually exceeded the budget of the Cabinet Office.

The following are some other numbers concerning the overall picture of public works in Okinawa. When one looks at the publications of the West Japan Construction Surety Co., Ltd. entitled, “Trends in Public Works Construction in Okinawa Prefecture,” the Government’s budget for Okinawa decreased and the Okinawa Defense Bureau’s budget for 2017 increased to 140.9 billion yen, out of a total budget of 382.6 billion yen, which was a 12.8% increase over the previous year—a big increase.16 2017 was a year when the public construction works expenses of the Cabinet Office, Okinawa Prefecture, and municipalities had decreased.

In response to the Okinawa Prefectural [Government]’s aiming for an “economy not dependent on the bases,” the Abe administration, without hesitation, developed a policy of increasing base dependency by decreasing the general budget and greatly increasing the defense budget. Looking at the budget data makes it easy to see what the Abe administration did. The data shows that they greatly loosened the foothold of Governor Onaga’s Prefectural Government and took a heavy-handed approach that silenced the opposition (Figure 4).

|

The explanation that the Administration gave about the reasons for the increase in the defense budget was “it is not intentional. It is due to orders for base-related construction projects that had not been actualized during the previous budget year.” If that is true, then the Administration would need to explain why the budgets of the Cabinet Office and Okinawa Prefecture had to be dramatically cut, but they did not provide an explanation about that. The West Japan Construction Surety Co., Ltd. that provided the data that aroused criticism withheld such data for some reason in the following budget years. The way they handled these questions is inexplicable.

“Realignment subsidy” trap

In March of this year [i.e., 2018] after the Nago City election, a problem arose concerning provisions for the “U.S. Military Base Realignment Subsidy” in connection with the new U.S. military base in Henoko. In the election for the Nago City mayor in February, the incumbent Inamine Susumu (1945-), who opposed the Base, lost the election. Toguchi Taketoyo (1961-), whom everyone expected would tolerate the new base construction, won the election. With that in the background, the Abe administration decided to once more start up the Realignment Subsidy that had been suspended during the previous mayor’s term.

The Realignment Subsidy is money that is distributed to municipalities “for cases in which, after having considered the level of impact that the ‘realignment’ [base construction] has on the residents’ lives, it is recognized that the subsidy will promote harmonious and certain realignment implementation.” The new mayor Toguchi [Taketoyo, who took office on 8 February 2018] has not made clear whether he agrees or disagrees with the new Henoko base, either during the election campaign or after he took office, saying that he “will closely observe what happens in the court dispute between Okinawa and the Government.” Nevertheless, the Government has decided to provide [Nago City] this Realignment Subsidy.

An editorial in the Okinawa Times, a local newspaper, provided the following commentary:

|

The Defense Ministry explained their decision to restart the subsidy because “the previous mayor clearly stated his opposition to relocating the base to Henoko. The new mayor, on the other hand, is neither in favor nor opposed to the relocation.” Mayor Toguchi emphasized that he would “act in accordance with the law. That does not constitute acceptance in any sense.” About the 15 billion-yen subsidy of 2017, the plan of the Defense Ministry is to carry that amount over to 2018 and make those funds available. The fact that they restarted the subsidy means that the Bureau recognized that Mr. Toguchi was “instrumental in the smooth and sure implementation” by not making it clear whether he was in favor or against the base relocation. In their view, they had gained the cooperation of Nago City. |

Their making the Realignment Subsidy funds available looks like an “act of bribery,” i.e., using tax money to stimulate [the Mayor’s] cooperation in the Realignment project even before he had made his position on the matter clear. Taking such funds is akin to the act of “accepting a bribe,” by deciding to go along with the Base in exchange for money. This is the kind of country we live in today, one where [government officials] can openly get away with this kind of thing.

Despite the fact that [acting in accordance with the law] “does not constitute acceptance” of the government’s new base construction in Henoko (the words of Mayor Toguchi), he accepted Realignment Subsidy funds, and such funds assume his acceptance and cooperation, so this amounts to a full-on “Realignment Subsidy fraud” where the Mayor has the Defense Ministry wrapped around his little finger. In the case that the Ministry distributes the Realignment Subsidy funds even without Mayor Toguchi’s acceptance, the Mayor says that he has not accepted the new base construction, and the Ministry is backstabbed by the Mayor, could the Ministry demand that the funds be returned? How would Japan’s Board of Audit interpret this way of disbursing a subsidy?

How Nago City spends the Realignment Subsidy funds is also a concern. Mayor Toguchi pledged during his election campaign that he will use it to “make pre-school tuition free of charge” and to “make school lunches free of charge.” At the Nago City council meeting in July 2018, members of the ruling and opposition parties debated how the Realignment Subsidy funds should be spent. Local media reported that city assembly members from the opposition agonized over the fact that “it is difficult to oppose a policy that benefits the citizens.” Mayor Toguchi, however, has not been accountable to the citizens; he has not explained to them that the free lunches and the free pre-school education were being provided to the children as compensation for the city accepting the base. He had a duty as the mayor to explain to the citizens, to the eligible voters, the pros and cons of going along with the Base construction before using the Realignment Subsidy funds.

To what extent is it permissible to use the Realignment Subsidy funds, which are part of the new Henoko base construction at Camp Schwab, for tuition and lunch waivers for the children of citizens of the “Nago City Urban District” along the coast on the west side of the city where children would hardly be hurt at all by the new base? The Henoko residents are the minority, and they are forced to live with the new U.S. military base and to suffer from it. Meanwhile, the citizen majority, those from the urban district, reap benefits from the “subsidy funds” after deciding among themselves to go along with the Base. The same sort of relation holds between Japanese citizens, who are the majority, and Okinawans. Japanese enjoy the illusion of “U.S.-Japan Security benefits” [or Ampo, i.e., the benefits reaped from the stationing of U.S. troops in Japan] by imposing the vast majority of U.S. military bases on Okinawa.

The trap of the “loophole economy”

Not all of the Okinawa Economic Stimulation funds that the Government gives to Okinawa are enjoyed by Okinawa. The Okinawa Prefectural Industry Development Association has requested that local companies be given priority in the case of orders for construction by major public offices.17 To take an example from the 2013 budget for construction commissioned by the Okinawa General Bureau of the Cabinet Office, 84% of the orders were to companies in Okinawa Prefecture. That’s looking at the number of orders. But if one instead looks at the amount of money spent, Okinawa’s percentage decreases to 51.6%, meaning that half of the apportioned government budget flowed back to companies based in mainland Japan. This is the problem of the “loophole economy”: Much of the government’s Economic Stimulation Budget that has flowed to Okinawa has actually wound up flowing back to the mainland of Japan, just like water flowing through a colander.

In the case of the budget of the Okinawa Defense Bureau for 2013, too, 87.2% of the orders went to local companies, but in monetary terms, that number falls to 70.7%. Looking at it another way, orders to companies outside Okinawa Prefecture totaled only 12.8%, but in monetary terms, 29.3%, or one third of it flowed to companies outside the Prefecture. With other (non-defense) national government and municipal public works taken into consideration, 17.8% of the orders for the same year went to companies outside the prefecture, but 43.9%, or nearly one half, of the total actual amount went to mainland companies. There was a slight improvement during the 2015 fiscal year: mainland companies got 14.7% of the number of orders, and 23.8% (i.e., one quarter) of the total amount.

Some are of the view that “Okinawa is flourishing thanks to the bases,” but the companies that are actually making the big bucks are the big general contractors from outside the Prefecture and other outside companies.

In the case of the new Henoko base construction, too, big general contractors from mainland Japan gain entrance while local Okinawan companies are only subcontracted or sub-subcontracted to by the big companies. 90% of the orders for construction and projects related to environmental impact assessments that were made before the construction began, went to companies that had revolving-door arrangements with the Ministry of Defense.

People from mainland Japan get the impression that Okinawa has a good economy due to fact that around 500 billion yen is spent on Okinawa annually in the form of budgets related to the U.S. bases and the Okinawa Economic Stimulation Budget, but actually there is the problem of the “investment-capital back flow” of the “loophole economy” due to the poor quality of the “yield.”

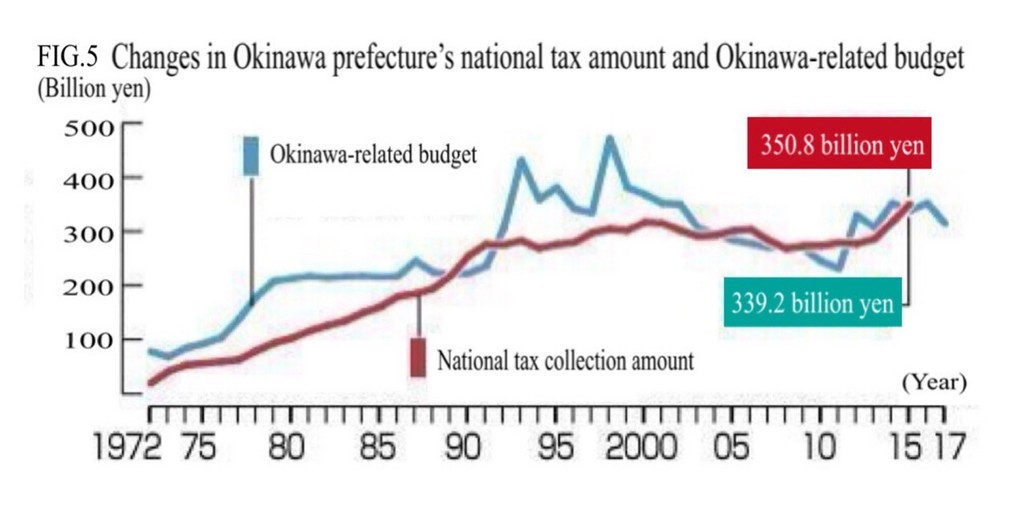

Miyata Hiroshi, who worked as a regulator, which is the highest non-career post at the Cabinet Office Okinawa General Bureau, says, “some people say that Okinawa Prefecture has received handouts from the government in the form of a whopping 300 billion yen every year from the special budget, but for the residents of the Prefecture, this is a humiliating thing to say. Okinawans pay more than 300 billion yen in taxes to the central government. Since 2015, on the contrary, the amount of tax paid to the central government has exceeded [the amount that Okinawa has received].” (See Figure 5). He emphasizes that “it is not true that they just take take take, and do not give back. In fact, Okinawa has become a prefecture that gives more than it receives.”

|

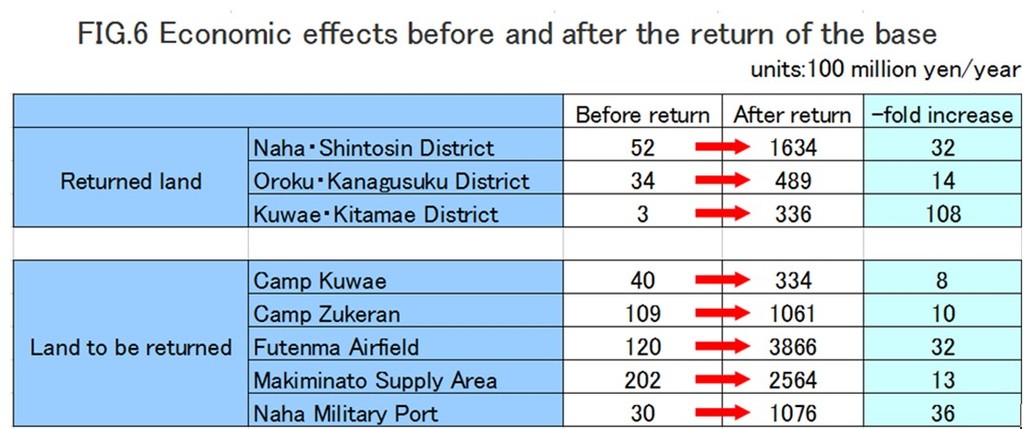

The whiff of change of the new 10Ks economy

During the years between when Okinawa reverted to Japanese sovereignty and 2018, during which some land on which U.S. military bases stood has been returned to Okinawans, the economy of Okinawa has shifted more and more away from an economy that is dependent on the bases to a base-independent economy. The background to this is the emergence in rapid succession of success stories, where plots that formerly had been used as U.S. bases were used in new ways by Okinawans. A summary of such successes appears in Figure 6—the extent to which land plots that had formerly been used as U.S. bases have been used effectively.

|

The Makiminato Housing Area [in Urasoe City, Okinawa Island] that was part of a U.S. base right in the middle of Naha City, was massively transformed into the “Naha City Shintoshin Area” [or Naha City New Urban Area] after it was returned. Before it had been returned, its economic effectiveness was 5.2 billion yen, but after it was returned, its economic effectiveness increased 32 times, to 163.4 billion yen.18 Even the military base facilities of Naha City were redeveloped as the Oroku Kanagusuku Area after they were returned, and the economic effectiveness of that plot of land has already increased 14 times, from a 3.4 million-yen base economy to 48.9 million yen.

According to Okinawa Prefecture’s tentative calculations, the economic output of Camp Kuwae (i.e., Camp Lester), which is scheduled to be returned in the future, will increase 8 times from 4 billion yen to 33.4 billion yen once it is returned. It is expected that the economic output of Camp Zukeran (i.e., Camp Foster) will increase 10 times from 10.9 billion yen to 106.1 billion yen, and that of Marine Corps Air Station Futenma will increase 32 times from 12 billion yen to 386.6 billion yen. It is anticipated that the return of the Naha Port Facility will result in 107.6 billion yen in economic repercussions compared to 3 billion yen in income from rent today.

With such a situation, it is fair to say that the “base economy” is “uneconomical” for Okinawa. Okinawa Prefecture has made public the results of an investigation that found that, in fact, “the existence of the bases leads to 1 trillion yen in losses annually.” It is expected that having U.S. military base lands returned and using this land where once stood military bases in new ways will lead to major profits and an accelerated rate of hiring.

The movement to break away from the base-dependent economy in Okinawa has been accelerating, boosted by successes occurring one after another. The late Prime Minister Hashimoto Ryūtarō (1937-2006) admitted informally that the Special Action Committee on Okinawa (SACO) of December 1996, in which 11 U.S. military facilities in Okinawa would be returned, was informed by the “Base Return Action Program” that was developed by then Governor Ōta Masahide (1925-2017) in early 1996, which put together a plan to regain all the U.S. military bases in Okinawa by 2015. In addition to the new 3Ks [“salary, holidays, and hope,” or kyūryō, kyūjitsu, kibō], a new 10Ks economy has been proposed. [The new, additional Ks, i.e.,] health, environment, finance, education, research, transportation, and commerce [kenkō, kankyō, kin’yū, kyōiku, kenkyū, kōtsū, kōeki] hold forth the possibility of developing new Okinawan mainstay industries.

Big changes continue to unfold, from already-existing tourism to excursion-style tourism, the “MICE” industry (meetings, incentive travel, conferences and exhibitions), and medical tourism; from aircraft-centered tourism to cruise lines; new concepts of constructing theme parks along the lines of Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium; and transitions such as that from the low-margin, high-turnover type to high value-added tourism.19

The offense and defense surrounding the gubernatorial election

On 18 November 2018 the Okinawa gubernatorial election will be held, something that happens once every four years.20 The top issue at stake in the 2018 gubernatorial election will be that of the new base construction in Henoko. Landfill work in the Henoko area of the sea has already begun, with an eye to new base construction. No matter who becomes the governor of Okinawa, the new base construction for Henoko will be rammed through, as long as the Abe administration holds onto power. As for the democracy of this country, we have a centralized government and a central-control state that does not respect local sovereignty. One searches in vain for any sense of crisis among the citizens of Japan concerning that lack of respect.

The issue of the new Henoko base construction that the Abe administration is forcing on us is all about the Marines’ new seaborne base construction scheme that the Marines planned in the late 1980s. But this construction project was postponed back during the days of the Vietnam War due to the particular conditions surrounding U.S. federal government financing then. And now what is pushed on us is the construction of a new U.S. base paid for with Japanese citizens’ blood tax, on the pretext of “getting rid of the danger of the world’s most dangerous base, Marine Corps Air Station Futenma.”

The U.S. secured the privilege of being able to freely install bases on the scale that they wish, in the places they wish, for as long as they through the conclusion of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty and the deal that was made through the Treaty of San Francisco that came into effect in 1952. The new occupation policy after the [San Francisco Treaty] Peace, which has been called the “bases-anywhere-in-Japan system” (zendo kichi hōshiki), allows for the maintenance of huge U.S. military bases within the interior of Japan even now 70 years after the War, with Japanese citizens picking up the tab for 75% of the costs of stationing troops on those bases.

Under the combined weight of U.S.-Japan Security Treaty and the U.S.–Japan Status of Forces Agreement, U.S. troops are allowed to enter and exit Japan freely without regulation of their disembarkation or embarkation; their taxes are reduced; Japan covers over half their utility bills; when they commit crimes they are not handed over until they are charged with a crime; and not only is the compensation that they pay to victims discounted but the Japanese government supplements such compensation with the taxes of Japanese citizens.

Right in the middle of the metropolis of Tokyo there exists a giant base for another country’s military, and although Japan is put in a subservient position with respect to Washington even in the air space of the Metropolis, none of the citizens of Japan are concerned about this, and they approve of this U.S. privilege. We cannot even keep track of how often occupying troops are forgiven for the violation of our laws. U.S. military aircraft are guaranteed free passage through the air space of our territory. And they get a free pass when they fly at low altitudes in residential areas.

Even if U.S. military aircraft cause accidents in our territory, our police do not have the right to investigate, we cannot protest even when they ignore our request to U.S. military authorities to investigate, and when they start doing flight drills after an accident whose cause has not been determined, all we can do is nod our heads.

How long do our Nation’s government officials plan to continue that kind of “relationship of equality between Japan and the U.S.”? When will they proudly pound their chest and say that this country is a “sovereign state”?

Okinawa is the “‘canary in the coal mine’ of democracy” in this nation. Over the course of the 70 years since the end of the War, even while we were overburdened with the U.S. military bases, we have obeyed the rules of this country, sought out help, and asked that the burden of the bases be lessened. When Okinawa ceases to raise their voices, when their voices no longer trouble you, that will mark the end of democracy in this country.

|

The cover of Maedomari’s Hontō wa kenpō yori taisetsu na “Nichibei chii kyōtei nyūmon” ([Introduction to the U.S.-Japan Status of Forces Agreement: Actually More Important than the Constitution], (Sōgensha, 2013). |

All notes below have been added by the translator.

Notes

Douglas Lummis, “The Most Dangerous Base in the World”. C. Douglas Lummis, “Futenma: ‘The Most Dangerous Base in the World’,” The Diplomat (30 March 2018)

Yoshikawa Hideki, “An Appeal from Okinawa to the U.S. Congress. Futenma Marine Base Relocation and its Environmental Impact: U.S. Responsibility” (沖縄から米議会への訴え 普天閒基地移設と環境影響 米国の責任は)

Maedomari discusses the importance of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty in John Junkerman, “Base Dependency and Okinawa’s Prospects: Behind the Myths: A Conversation with Maedomari Hiromori, Professor of Economics and Environmental Policy, Okinawa International University,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 14, Issue 22, No. 2, November 15, 2016. He sums up the situation this way: “Japan was required to provide land and facilities for US military forces, which it did by maintaining the bases on Okinawa. As long as the bases remained in Okinawa, the US was satisfied. So the bases have been retained in order to strike this kind of political balance.”

『沖縄の米軍及び自衛隊基地(統計資料集)』(Okinawa no Beigun oyobi Jieitai kichi tōkei shiryō shū [Collection of statistics on bases of the U.S. military and Japan Self-defense Forces in Okinawa]) 2018年3月、沖縄県知事公室基地対策課 (Okinawa-ken chiji kōshitsu kichi taisaku ka [Base Policies Division of the Okinawa Prefectural Governor Information Desk]), March 2018, page 104.

For those who have not seen with their own eyes the amazing commitment to non-violence among Okinawa protestors, see the writings of Douglas Lummis, such as where he writes, that the “riot policemen are not always that gentle. But the non-violent behavior of the sit-inners does have an effect on them.” (See here.) One could say that the protestors have won the respect of the riot police, if not that of Prime Minister Abe, who has not spent much time at the gate to Camp Schwab.

Gavan McCormack, “‘All Japan’ versus ‘All Okinawa’—Abe Shinzo’s Military-Firstism,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 10, No. 4, March 16, 2015.

Justin McCurry, “U.S. grounds Osprey fleet in Japan after aircraft crashes off Okinawa,” The Guardian (14 July 2017). Jeff Schogol, “Second Osprey incident on Okinawa,” Marine Corps Times (16 December 2016).

“U.S. military chopper bursts into flames on landing in Okinawa,” Kyodo News (11 October 2017). There was a crash in California in 2018 as well: Tara Copp, “Marines: 4 Dead in CH-53 Crash,” Marine Corps Times (4 April 2018).

“Object possibly from U.S. military plane falls on Okinawa nursery,” Kyodo News (7 December 2017). “Window falls from U.S. military chopper onto Okinawa school grounds,” Kyodo News (13 December 2017). “Okinawa shogakkō ni beigun heri no mado rakka jidō kara 10m hodo no bashō” [About 10 Meters from the Children Parts Fall from the Window of a U.S. Military Helicopter onto an Okinawan Elementary School] 沖縄小学校に米軍ヘリの窓落下 児童から10mほどの場所, News Web Easy (13 December 2017). Video available from Channel 7 News here.

Motoko Rich, “Former U.S. Marine Gets Life in Prison for Okinawa Rape and Murder,” New York Times (1 December 2017)

About the sexual violence, see for example, Jon Mitchell, “U.S. Marine Corps Sexual Violence on Okinawa,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 16, Issue 3, No. 4, February 1, 2018.

For more information, see the website of the Okinawa Prefectural Industry Development Association here.

This area was returned to Okinawa in 1987. See Okinawa-Information.com, “Shintoshin Shopping Area, Naha Okinawa“.

The election was actually held on 30 September 2018 due to the death of the former governor, Onaga Takeshi.