The COVID-19 pandemic generates many uncertainties for everyone, but for Asia’s poor and marginalized, there is little doubt about the devastating consequences. It’s not only about unequal access to public health care, but also the loss of livelihoods that wreaks havoc in disadvantaged communities living on the edge of subsistence that are more likely to experience police abuses under the pretext of lockdown and quarantine enforcement. As second and third waves strike, the menace of this coronavirus and the high risk of letting our guard down becomes all the more evident. Resurgences of cases in Australia, Hong Kong, and Japan provide stark reminders that turning the corner does not mean being out of harm’s way. Much debate focuses on the trade-off between public health and jobs as various degrees of lockdowns boost unemployment, especially for contingent workers. Moreover, the contagion of fear and anxieties about the future, along with travel restrictions and closed schools, keep people at home and purse strings tight, forcing many businesses to close in a downward spiral of contraction and dislocation. Despite governments around the region rolling out various countermeasures to soften the economic pain, including massive stimulus packages, these schemes are but a band-aid. Even relatively prosperous nations remain vulnerable to the gathering economic typhoon, because the pandemic is a transnational catastrophe that is disrupting markets and supply-chains while battering down growth rates and demand.

This Part 2 of Pandemic Asia features essays on South Asia (Bangladesh, India, Nepal and Sri Lanka) and Southeast Asia (Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand). In addition, Sidney Jones of the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict (IPAC) discusses the thus far limited impact of the pandemic on transnational regional terrorism. Across Asia, migrant labor has played an important role in regional economies, but the pandemic has served to highlight their precarity and the impact on families and economies dependent on their dwindling remittances.

South Asia

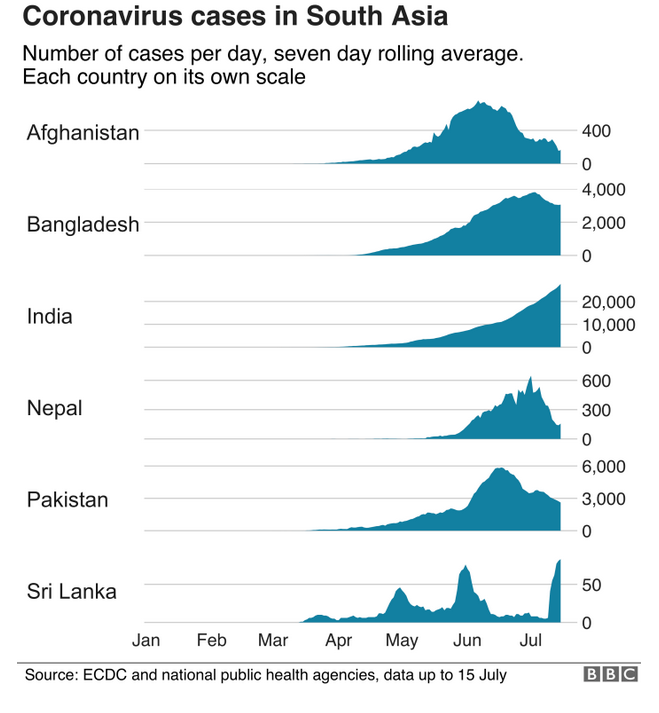

The total number of cases in South Asia is relatively low per capita, but this is attributed to a low rate of testing (Menon 2020). India has conducted some 10.3 million tests in a population of 1.3 billion and about 1.3 million tested positive. Bangladesh has recorded 196,323 infections as of July 16, but the official data suggests a downward trend. This encouraging development generates a sense of relief that has been tempered by reports of a brisk trade in fake negative test certificates. Such developments reinforce doubts about the reliability of official statistics in a region where spending on public health care infrastructure has been low. Relatively low mortality rates could be due to the higher proportion of young people in the population, but also might be inaccurate. The recent rise in infections in Africa suggests that the relative youth of a population does not inoculate nations or regions against COVID-19. Writing about COVID-death shaming in Pakistan, Mohammed Hanif also suggests that the official statistics might reflect a combination of weak reporting protocols and the strong stigma against confirming infections and COVID-19 related deaths (Hanif 2020).

Sajid Amit examines the pandemic’s impact on Bangladesh’s economy, dependent as it is on garment export revenues and remittances from overseas migrant workers. Masses of garment orders have been cancelled due to plunging demand while many overseas migrant workers have lost their jobs. Global economic forecasts provide little hope for a rapid rebound in either sector. The plunge of income for these workers will curtail consumer demand inside Bangladesh while overextended garment industries will have trouble servicing their loans, undermining the financial sector. The coming economic typhoon threatens the entire region with massive dislocations well beyond government capacity and willingness to protect, especially the vulnerable and destitute who are always relegated to the back of the line for handouts.

Also writing on Bangladesh, Ikthisad Ahmed focuses on the political economy of the pandemic. He argues that an authoritarian government has undermined civil liberties, overlooked the plight of the vulnerable in favor of big business, pandered to fundamentalist Islamic groups, and bungled outbreak countermeasures. The result has been to transform a crisis into a disaster.

Similarly, Mukta Tamgang is withering about the government’s response in Nepal where wishful thinking delayed countermeasures and the capacity of the health infrastructure proved inadequate. He examines how the return of dismissed migrant workers from India spread transmission, chiefly because they were kept in crowded quarantine facilities along the border which served as COVID-19 incubators. In addition, rural migrant workers in Kathmandu suddenly lost their jobs and had no choice but to return to their home villages, exposing relatives to the pandemic. As in other Asian societies plunging into this pandemic, class plays a significant role in shaping the outbreak experience. Under fire for bungling crisis countermeasures and likening the coronavirus to flu while addressing the National Assembly on June 19, Prime Minister Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli prorogued Parliament on July 2 in order to cling to power (Ghimire 2020). Apparently, he feared a no-confidence vote and faces rebellion within his own party. Tamgang writes, “Rather than focusing on the issues of the impending pandemic, unemployment, and plight of the marginalized, he tried to distract the public by resorting to inflammatory nationalistic rhetoric, such as asserting Nepali claims to a boundary also claimed by India. He has also taken further steps to curtail civic freedoms and to control the media in a series of autocratic moves.” This trend toward autocratic governance seems to be yet another contagion in the region.

Sri Lanka was relatively successful in containing the outbreak since April by imposing a strict lockdown and thorough testing, tracking, and quarantine, but after reopening schools in July, it closed them again due to a spike in cases. Parliamentary elections are scheduled for August but may be delayed in affected regions. Udan Fernando also sees signs of creeping authoritarianism in Sri Lanka, noting that recently elected President Gotobhaya Rajapaksa has exploited the corona crisis to bypass the judiciary and legislature while expanding executive powers and consolidating his grip on power. Similar to Nepal, the military has assumed a prominent role in the crisis response, and as in Indonesia, this has provided an opportunity for the armed forces to regain lost ground and reassert their prerogatives.

Samrat Choudhury covers the pandemic raging in India, blasting the government for prioritizing public relations over public health. He writes, “Bigotry, superstition, and poor governance worsened an increasingly bad situation in which government efforts to suppress unfavorable news censored information that would have been useful in containing the disease. A lockdown imposed without warning crashed the economy and caused immense suffering to millions of internal migrant workers who abruptly lost their livelihoods. Poor internal migrant workers were worst affected.” He further explains how the pandemic crackdown rescued the government of PM Narendra Modi from escalating demonstrations against his Islamophobic legislation aimed at stripping Muslims of their citizenship. The lockdown-driven exodus of jobless migrants from urban areas to their rural villages facilitated transmission and now India has surpassed 1.3 million cases of COVID-19 with over 30,000 deaths as of July 24, the highest in Asia. The nation’s creaky health infrastructure has been overwhelmed and it appears the worst is yet to come.

Southeast Asia

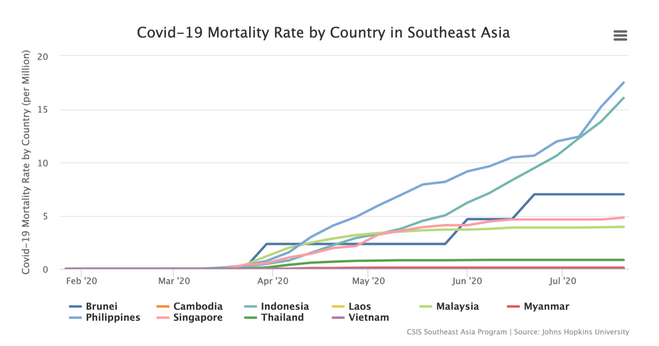

The limited outbreak in the Buddhist mainland states of Southeast Asia (Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos) contrasts with the far greater extent of transmission in insular Southeast Asia (notably Indonesia and the Philippines). Why this is so remains uncertain, but religious differences are not a viable explanation. In multiracial Malaysia, where a majority are Muslims, there are just under 9,000 confirmed cases and 123 deaths in a population of 32 million, while Indonesia, the most populous Islamic nation in the world with nearly 275 million citizens, reports over 91,000 cases and nearly 4,000 deaths. Neighboring Singapore, a multi-religious city-state where Buddhists are the most numerous, has over 48,000 cases but only 27 deaths. Vietnam, on the other hand, a nation of 97 million that is officially communist and atheist, boasts the best record of containment of the pandemic in the region with no reported COVID-19 deaths. In Southeast Asia, the mostly Christian Philippines has recorded the second highest number of infections (with more than 68,000) and deaths (approaching 2,000) as of July.

The low number of fatalities in the Buddhist mainland SE Asian states might be due to uneven reporting, but probably owes more to social habits of limited body contact and sensible precautions adopted by citizens who know they can’t expect much from their governments. Having little reason for putting faith in public officials, they have responded accordingly with common sense practices such as adopting informal quarantine measures.

Source: Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS)

On Singapore, Fangpi Liao highlights government zigzagging on containment policies and what amounted to a lockup affecting 300,000 migrant workers in cramped dormitories. The ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) called an election to take advantage of the COVID-19 crisis, hoping for a robust mandate in preparation for a leadership transition, but in “winning,” garnered its second lowest percentage (61%) of the popular vote ever. Given all the advantages baked into the system that favor the PAP, and sustained efforts to stifle dissent and criticism, the results amount to a stunning rebuke for the ruling elite. As Liao writes, “The response demonstrated not only the cynicism of the PAP leadership, but its utter incompetence, shattering the party-state’s carefully-crafted façade of technocratic mastery. Perhaps the best that could be said of such a sorry performance is that despite the effective imprisonment of hundreds of thousands of foreign workers, the economic disruption and psychosocial devastation caused by a lockdown of nearly 6 million “community” members, and the terrifying risk posed by the ruling party’s decision to hold an election during a plague it was clearly incapable of managing, the number of COVID-19 deaths remained low by international standards, with under 30 fatalities out of over 40,000 confirmed cases by July 2020.”

Thailand has done reasonably well in containing the pandemic with about 3,300 cases and 58 deaths, generating an air of triumphalism over a war that the government asserts is as good as won. Yet, as the world is coming to understand, complacency remains a big risk, as containment “is more a process of resilience and a sustained effort of management, mitigation and minimisation, overcoming and outlasting a deadly virus that will be around for a long time.” (Thitinan 2020) In Thailand, former army chief Prayuth Chan-Ocha seized power in a 2014 coup, and as prime minister won disputed elections in 2019. Pavin Chachavalpongpun argues here that the Prayuth government has exploited the pandemic to retain emergency powers, stifle pro-democracy dissent, and entrench the military. As such, he believes the pandemic has reinforced authoritarian practices in Thailand. It appears that containing the pandemic may be easier than satisfying democratic aspirations. On July 18, thousands of young Thais demonstrated against the government at Bangkok’s Democracy Monument, defying restrictions on large gatherings (The Guardian 2020). This anti-government rally, the largest since a state of emergency was declared in March 2020, was organized by the group Liberation Youth, and called for an end to repressive laws, a new constitution, and fresh elections.

The number of infections in Indonesia exceeds that in China, but the official tally is suspect due to the limited scope of testing. The government has drawn sharp criticism for easing restrictions even as the number of cases rose, maintaining that reviving the economy is critically important to generate jobs and income. This is the trade-off that leaders across the region and throughout the world are grappling with, weighing the uncertain risks of COVID-19 against the certain catastrophe of losing jobs in the event of closing the economy.

Beyond the public health and economic impact, the politics of pandemic holds significant ramifications. As Jun Honna argues here, the outbreak has been a golden opportunity for the Indonesian military to reassert power and claw back lost turf by overturning reforms and constraints imposed since the downfall of President Suharto in 1998. He doesn’t see this as a prelude to the military reclaiming a dominant political role or evidence of democratic backsliding. Instead, he focuses on how the military has exploited the crisis to advance institutional interests and boost morale within the context of democracy.

In the Philippines, the government recently announced a controversial policy of dispatching police door to door to bring COVID-19 patients to quarantine facilities, even if they have mild symptoms or are asymptomatic. The new policy is in response to a rise in cases after easing some lockdown restrictions but contradicts the government’s previous advice for such patients to self-isolate. Rights groups have condemned the new policy as draconian and reminiscent of the extensive extrajudicial killings, some 27,000, associated with President Rodrigo Duterte’s notorious “drug war.” The police have already come under fire for rights violations and abuses of those alleged to have violated curfews and quarantine regulations, reinforcing public concerns that Duterte has militarized the pandemic response at the expense of human rights. This new order dispatching police to homes coincides with a new anti-terrorism law that grants the government broad new powers to crack down on dissent, similar to the Marcos-era martial law. The new law is also in line with Duterte’s assault on freedom of the press. Here, Nastassja Quijano, Maria Carmen (Ica) Fernandez, and Maria Karla Abigail Pangilinan write that, “the Philippine government’s prioritizing of punitive policies such as detaining quarantine violators or attempting to decongest Manila by sending poor families to neighbouring provinces, magnifies existing socio-spatial inequalities and further spreads disease. In many of these communities, poverty is a comorbidity.” While Duterte’s “highly securitised approach has led to multiple cases of excessive use of force by police,” such abuses are not equally experienced as, “alleged violators from poor communities get punished immediately, [while] the treatment and handling of violations in affluent communities and positions of power tends towards greater leniency.”

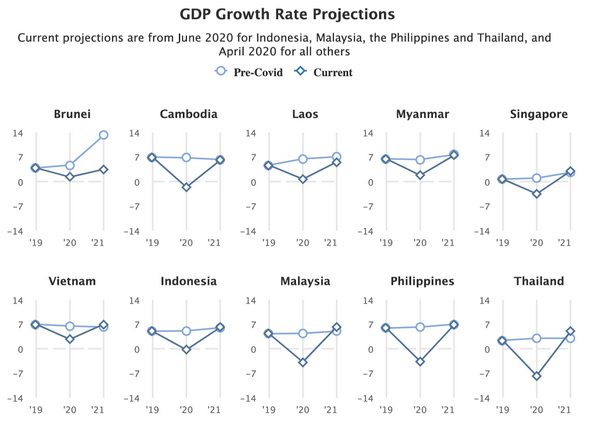

The privileged will also enjoy advantages in weathering the sharp economic downturn, but growth rate forecasts suggest the pain will be widespread and there is concern that the rebound may be slower and more uneven than currently projected.

Authoritarian Creep

Regarding the broader political implications of the pandemic, Dan Slater observes: “The issue is not whether democracies or authoritarian regimes are responding better to the pandemic. It is whether the stronger, bigger states emerging from the pandemic will be entirely authoritarian and unconstrained, or whether citizens will enjoy any democratic protections against this expanded state power” (Slater 2020). He warns that, “There can be little doubt that Southeast Asian societies will have stronger states in place to protect them in the wake of this pandemic. Whether those societies will be able to protect themselves from those stronger states is a different matter entirely” (Slater 2020). With the pandemic providing cover for authoritarian creep, leaders have tried to entrench emergency powers and stifle dissent, but a stronger state in this sense doesn’t mean more capable or effective governance and might not be sustainable in the long run. There is nothing like a failed pandemic response to discredit leaders and generate a backlash.

Prejudice and Pandemic

Linda Hasunuma’s powerful reflection on Trump-sponsored hatemongering against Asian Americans probes the nexus of privilege, discrimination, and marginalization of minorities in the US in a time of pandemic. Disparate groups of Asian Americans are now lumped together as “Chinese” and blamed for the outbreak, confronting a virulent eruption of racism among whites and lack of empathy from other minorities. She shares her experiences of hateful looks, discrimination, and avoidance, while reflecting on how Asian Americans have offered little support for Blacks, Latinos, and other minorities.

Security Implications

On the geopolitical front, Giulio Pugliese analyzes the implications of souring Sino-US relations, focusing on how the Trump Administration’s hyping of the China threat and hardline countermeasures are designed to boost prospects for his reelection. He argues that, “COVID-19 is cementing Sino-American strategic rivalry and crystallizing Washington’s maximalist pushback against Beijing, with implications that go well beyond the region. High-stake geopolitical manoeuvrings between the US and China are impacting economic, political and security dynamics globally. More importantly, the ongoing political warfare between the two – one that has been exacerbated by the pandemic – is cementing US-China enmity and reifying the new “Cold War”.” In his view, Trump’s opportunism in backing an escalating confrontation marks a radical break from five decades of US engagement with China. He concludes, “a potential Biden presidency or Democratic-led Congress will become warier of undoing some of the anti-China legacy of the Trump administration. While it is too early to declare a US-China “Cold War”, China’s assertiveness and the US maximalist pushback are working in lockstep to reify the Cold War trope past the 2020 US presidential elections.”

Sydney Jones surveys the impact of the pandemic on terrorism, concluding that, “Violent extremism in Southeast Asia did not increase as a result of COVID-19 despite exhortations from ISIS leaders to attack, nor was counter-terrorism capacity seriously undermined by the need to divert funds and personnel.” She adds, however, that, “Fears remained that the pandemic might increase interest in biological weapons or cyber-attacks; create a favourable climate for recruitment as economic hardship deepened; or lead to prison uprisings.”

The pandemic may hold profound implications for the way of war. The March outbreak of COVID-19 on the USS Theodore Roosevelt aircraft carrier is one of several recent cases highlighting the risk of the pandemic to combat readiness of US forces deployed around the world (Kale 2020). The TR, as it is called, had to suspend patrols and remain in port while almost the entire crew was evacuated. COVID-19 outbreaks were reported for at least forty other US warships, highlighting the problems of relying on the fleet to project power and prevail against enemy forces. The other armed services have discovered the same coronavirus complications affecting their readiness and doctrines. Some joint training-and-combat exercises with US allies in Asia have been conducted recently, such as the parallel “Quad” exercises involving the navies of the US, Japan, Australia, and India that target China. Yet, it is likely that other joint exercises will be scaled back or postponed. These exercises, designed to improve cooperation, interoperability and readiness while sending a warning signal to adversaries, now confront a new, invisible enemy and a need for isolation and distancing that hinders them from fulfilling their purpose.

On Okinawa, an outbreak among the roughly 25,000 US troops stationed there has reinforced anti-base sentiments at a time of tensions centered on US-Japanese plans for a new Marine base while highlighting the lack of transparency that shrouds the US military presence (Feffer 2020). US forces are exempt from Japanese immigration regulations that currently ban travel from the US. The US Department of Defense set a policy of non-disclosure for COVID-19 infected military personnel out of concern that it might compromise operations, but after reports of cluster infections, Okinawan Governor Danny Tamaki obtained special permission from the head of US forces in Japan to disclose details of the outbreak on US bases in the prefecture. This damage control highlights how insulated the US military is from local accountability, a lack of transparency that feeds rumors and breeds resentment. The number of reported cases among US military personnel on Okinawa reached 143 in July amid reports of lax enforcement of quarantine-on-arrival containment measures. US bases elsewhere, including South Korea, have also been hit by the pandemic, forcing lockdowns and stepped-up quarantine measures. The US is the epicenter of the global pandemic and as such, base-hosting nations are justifiably concerned. This means US military forces deployed overseas should act more responsibly and be better “neighbors,” but what else is new?

Meanwhile, President Trump is pressuring PM Abe Shinzo to quadruple what Japan pays annually in support of US forces in Japan to some $8 billion. The Abe government has appreciated Trump’s hardline on China but is likely to slow-walk negotiations in the hope that come the November elections the pandemic solves their Trump problems. Longer term, doubts are building whether these bases are useful for either US or Japanese security or are just sitting ducks for enemy attacks that paint a bullseye on local communities.

Assuming that this pandemic will linger, and anticipating the risks of unpredictable new pandemics, military strategists are accelerating ongoing plans to rethink the global posture of U.S. deployments and operations (Klare 2020; Stavridis 2020). Just as pandemic-driven teleworking is gaining acceptance and reshaping work-place practices, plans to deploy unmanned systems and killer robots, and further tap the potential for AI and networked operations, are gaining momentum. In the post-pandemic world, the way of war is being transformed, given a boost by the need to manage the new risk environment. This may lead to downsizing or eliminating some overseas garrisons, forward deployment of U.S. forces, and large fleets of manned warships, but vested interests will slow such changes. The pandemic may alter military doctrines and tactics but will also be invoked to justify budgets and existing wish lists.

It is hard to gauge the full gamut of security implications stemming from COVID-19, but as the death tolls and budget deficits rise, and economic and social reverses gain momentum, this global inflection point may generate new political forces that challenge flailing and flailed states and ways of governance, a nexus of opportunity, instability, and repression. In this pandemic dystopia, states have gained more sweeping powers to stifle dissent, silence critics, invade privacy, and curb civil liberties, but in our uncertain times, is this a sustainable model? Perhaps not, but the trend towards authoritarianism in South and Southeast Asia shows few signs of abating.

Sources

Aspinwall, N., 2020. “The Philippines Announced New Coronavirus Measures Alarming Rights Groups”, The Diplomat, July 17.

Abuza, Z. and B. Walsh, 2020. “The Politics of Pandemic in Southeast Asia”, The Diplomat, June 2.

Feffer, J., 2020. “Okinawa: Will the pandemic transform US military bases?” Responsible Statecraft, July 17.

Ghimire, B., 2020. “Sudden Move to Prorogue Parliament Undermines Legislature, Experts Say”, Kathmandu Post, July 5.

The Guardian (2020) “Thousands of anti-government protesters rally in Thailand’s capital”, July 18.

Hanif, M., 2020. “What’s with all the Covid-death shaming”, The New York Times, July 16.

Klare, M., 2020. “The Pentagon confronts the pandemic”, TomDispatch, July 19.

Menon, S., 2020. ”Coronavirus in South Asia: Is a lack of testing hiding the scale of the outbreak?” BBC, July 20.

Slater, D., 2020. “Southeast Asia’s Grim Resilience: Pragmatism amid the Pandemic”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 1.

Stavridis, J., 2020. “Six Ways the U.S. Isn’t Ready for the Wars of the Future”, Bloomberg, July 10.

Thitinan, P., 2020. “Covid Success Coming at a Heavy Price”, Bangkok Post, July 17.