Abstract: In the case of Bangladesh, COVID-19 has laid bare the shortcomings of the state, underscoring the complicity of the military, elite class, Islamists and intelligentsia in the government’s dysfunctional, apathetic, and authoritarian approach. This essay breaks down the Bangladeshi government’s response along three key lines: the first to examine the legal basis for its response to the pandemic, the second the exploitation of labour rights and how it affects public image, and third the suppression of freedoms of speech and expression. Through discussion of these key tenets, this essay provides a comprehensive indictment of how Bangladesh is turning a crisis into a disaster.

In Bangladesh, the emperor unquestionably has the best clothes. In order to display them, a parade on horseback that would span the entirety of 2020 and go throughout the country was planned to celebrate the birth centenary of the ruling dynasty’s founding father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. It was to be inaugurated by India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi in order to reaffirm the special relationship between Bangladesh and India that has helped to solidify authoritarianism in Bangladesh over the past decade. The launch of a Mujib calendar beginning on 17 March 2020 – the date of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s birth centenary – would kick-off the nationwide, year-long roadshow. It would end at the beginning of the celebrations for another year-long affair: Bangladesh’s fiftieth birthday in March 2021. This thoroughly choreographed public relations extravaganza suits autocrats like Rahman’s daughter, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. The 2018 re-election campaign platform of the Awami League declared that it was the only party that could guarantee Bangladesh’s history was properly respected, citing these upcoming celebrations as evidence of its commitment to doing so. Although the rigged election denied the Awami League the veneer of democratic legitimacy, it was hoped that the nationalist pageantry would provide a positive limelight. Taxpayers would provide much of the funding for the two-year saturnalia, supplemented by large donations from cronies who have done well from their connections to the Awami League. But things did not go according to plan.

|

Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina with portrait of her father Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (Credit: YouTube.com) |

On 6 March 2020, demonstrations erupted in the capital of Dhaka, demanding Narendra Modi’s invitation be rescinded due to the passage of his BJP government’s discriminatory National Register of Citizens and the Citizenship Amendment Act that are designed to strip Muslims of their citizenship rights (Akash and Sarker, 2020; Daniyal, 2020; Haider, 2020). In Muslim-majority Bangladesh, while most protesters were Muslims and Islamists, secular and progressive activists also took to the streets to stand against bigotry. Just two days later, on 8 March 2020, three cases of COVID-19 were confirmed in Bangladesh (Paul, 2020). On 9 March 2020, Narendra Modi cancelled his planned visit on the pretext of taking precautions against the encroaching global pandemic (Daniyal, 2020). The same day, the Health Minister guaranteed to the nation’s press that Bangladesh was fully prepared to tackle an outbreak (Ahmed and Liton, 2020). On 17 March 2020, a pared-down version of the events that were to kick off the centenary celebrations went ahead with the participation of foreign artists, including those from India, and were watched by tens of thousands gathered in public places (SOMOY TV, 2020). Sheikh Hasina addressed the nation, but instead of offering sensible advice about pandemic countermeasures, she focused on glorifying her family dynasty and rallying nationalist sentiments. (TBS Report, 2020a). On 26 March 2020, a ten-day nationwide general holiday – not a lockdown – started, ostensibly to stop the spread of COVID-19. The prime minister touched on it during her midnight Independence Day address on 26 March (Tribune Desk, 2020a), invoking the spirit of 1971 – the Awami League’s version of shahada (Muslim profession of faith that there is no god but Allah) declaring itself to be the nation’s one and only party – and confidently declared that her party had ensured that Bangladesh was completely prepared to tackle a disease which it had been downplaying and was ill-prepared to contain or mitigate. Between 8 and 26 March 2020, apologists and ministers and senior members of the Awami League publicly restated their unshakeable faith in Sheikh Hasina, a collectively ineffective response to the developing COVID-19 crisis (UNB, 2020a).

The legality of dealing with a global pandemic

The Awami League has defined democracy in the narrowest terms possible in order to continue to lay claim to it. The Constitution of Bangladesh allows the government to declare a state of emergency, which suspends the Constitution and the rights enshrined in it, to deal with extraordinary circumstances (Section 141B, Section 141C of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh). While COVID-19 spread, however, the Awami League refused to declare a state of emergency. This could be admirable, were the reasons behind it not so self-serving. Other than the period in which Bangladesh Nationalist Party’s (BNP) attempted to establish one-party rule, the last time this constitutional provision was enacted, a civil society-backed military government (supported by the West) openly belittled democracy (BBC News, 2007; The Economist, 2007). Civil society elites – including Nobel laureate, Muhammad Yunus, renowned lawyer and one of the drafters of the Constitution, Kamal Hossain, and editor of the widest circulating English language daily, Mahfuz Anam – ensured the suspension of civil liberties and democracy. They asserted this was a high-minded effort to rescue the nation from dysfunctional politics. The two traditional political powerhouses, the Awami League and the BNP, faced an existential threat during the nearly two-year “civil society” government when fundamental rights were suspended.

The lesson learned from that hiatus was to nip in the bud any political machinations by opponents and fend off of another civil society or military takeover. Since that interim government, the Awami League’s eleven-year reign has been one long mission to avoid antagonising the military, appeasing it instead with state patronage, lucrative contracts, and a mutually beneficial bridge between it and the party, all with the goal of neutralising its political threat. For example, Sheikh Hasina’s government promoted Aziz Ahmed, despite familial links to organised crime, to the position of Chief of Army Staff, over more senior and eligible candidates (Khokon, 2018). The selection of Saiful Alam as the new head spy at the nefarious Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI), Bangladesh’s military intelligence agency, during the ongoing health crisis was yet another partisan move to assert civilian control over state security forces (bdnews24, 2020).

The Awami League thus avoided declaring a state of emergency and kept COVID-19 related deployment of the military to a minimum. The presence of men in uniforms is most keenly felt by the refugee and indigenous populations, who the military has been tasked with monitoring and oppressing (Ahmed, 2014; Hill Voice, 2020). This arrangement predates the pandemic, and the minority communities overseen by the military are amongst the most vulnerable to the pandemic due to endemic poverty and poor public health services (Ahmed, 2014). Furthermore, the police and the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), a specialist paramilitary force, have been at the forefront of the government’s COVID-19 response, disabusing people of the notion that Awami League is wary of using force (Riaz, 2020a; Netra Report, 2020a). Law enforcement agencies meting out corporal punishment and humiliation to the lower classes became a staple of state propaganda carried by media outlets as proof of the pandemic being tackled (Rabbi and Rahman, 2020). The government’s response has thus prioritized law enforcement, not healthcare. The government has refrained from invoking the notorious section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP) – a colonial era law that endows the state with sweeping security powers such as curfews and bans on mass gatherings – but this has hampered containment efforts. Awami League proponents cite the absence of a state of emergency and curfews as evidence of its democratic commitment, but critics counter by citing the securitization of the COVID19 response.

In the absence of declaring a state of emergency or imposing curfews, the legal basis for Bangladesh’s COVID-19 response is murky at best. The various strategies used worldwide broadly fall into two categories: (1) strict lockdowns to contain transmission, with optimization of resources and a focus on building healthcare capacity, and (2) social-distancing based restrictions without a formal lockdown, with emphasis placed on testing, contact tracing, and mitigating the impact of the pandemic. The Bangladesh government has been dysfunctional and not developed a strategy that resembles either of the above. The Awami League eschewed lockdowns in favour of a general holiday, extended until the end of May 2020 (Mamun, 2020), although it was obvious by then that more, not less, needed to be done regarding restrictions (Dhaka Tribune, 2020). It has thus failed in its most basic duty to protect the people. The general holiday enacted in lieu of a lockdown has neither been legally defined nor derives from existing laws A long overdue Infectious Diseases (Prevention, Control and Elimination) Act (IDA) was made law in 2020 (The Daily Star Law Desk, 2020), and extended to include COVID-19 under its jurisdiction, with a gazette issued on 23 March 2020, as required by the Act for diseases not listed in it (Government Gazette Archive). However, rather than being prescient, the Act and its application have merely exposed the inadequacies of the existing system and incompetence of the authorities.

While the IDA allows for the formulation of prevention strategies that may include isolating infected individuals and closing down infected sites, it does not provide detailed procedures for how those things should be done, in general nor specifically regarding COVID-19. The Director General of the Department of Health, with the assistance of an Advisory Committee that includes the Minister of Health and secretaries of specified ministries, is solely authorised to enact prevention measures, and they are to be carried out by the Department. Contrary to this, Bangladesh has been following the orders of the Prime Minister, and the law enforcement agencies that have been implementing them. Spokespeople who became the identifiable faces of the government’s response were drafted from the little-known Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR), which lacks jurisdiction under the IDA, and the Minister of Health who is at most empowered to act in an advisory capacity under the Act (Ahmed and Liton, 2020). The necessary committee of healthcare experts was not formed until 18 April 2020, and even then, it was not properly constituted (Transparency International Bangladesh, 2020). In simple terms, in the face of an overwhelming threat, there was no leadership or transparency from those on high.

Not only is the IDA insufficient in codifying the healthcare procedures necessary to tackle COVID-19, it also does not provide a legal basis for lockdowns, general holidays, definite or indefinite closures (of offices, educational institutions, public places etc.), government assistance schemes and their oversight, nor accountability (Imam, Re., 2020). There are no provisions to deal with the inevitable consequences of a pandemic, ranging from operation of the judiciary and other organs of state, aid and relief packages, stimulus and loan packages and repayment schedules, and healthcare staff and resource shortages, to accessing food, water and shelter, employment protection, volunteers’ and tenants’ rights, loss of income, health and safety rights, and poverty (ibid.). The Act does not reaffirm the right to life of patients or healthcare professionals, allowing Sheikh Hasina and her government to blame, attack and abuse victims of their actions, or lack thereof, during the ongoing health crisis, in direct contradiction of the Constitution, and of numerous international agreements that the country is party to (Imam, Ra., 2020). The Prime Minister’s public rebukes explicitly accused doctors and nurses of criminal conduct despite their working on the frontlines without personal protective equipment (PPE) at considerable personal risk (Rahman, 2020), while her Special Adviser, the Member of Parliament (MP) Salman F. Rahman, exported millions of PPE to the USA through his Beximco conglomerate (TBS Report, 2020b). Severe shortages of PPE across the world have paved the way for domestic price hikes, and for entrepreneurs to chase similarly lucrative ventures (Transparency International, 2020). Government procurement of essential medical equipment and supplies has been at five to ten times the standard rates, with the already prevalent problems of overpricing and false invoicing amongst the producers and importers of medical equipment amplified by opportunists taking advantage of the crisis (Himal Editors, 2020).

The IDA expressly states the importance of the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) regulations and guidelines, but these are flagrantly violated in practice. A concerted and coordinated effort of the media, intelligentsia, and the elite class – all extensions of the government – has zealously and relentlessly discredited the WHO while sowing seeds of Sinophobia. The resulting spread of misinformation and disinformation to downplay the pandemic and distract attention from the state’s failure to deal with the growing crisis, has effectively dissuaded citizens from taking measures to protect themselves. The error of looking westward at a time when more comprehensive and reliable methods of countering COVID-19 are available regionally, and when typical world-leaders like the USA and UK in particular are struggling, is lost on the beholden intelligentsia and elite class. In simultaneously using the failures of the West as a yardstick to proclaim Bangladesh’s relative success while actively replicating the worst aspects of Western strategies, the ruling elite have abnegated their duty to protect ordinary citizens. Beximco and the loosely regulated pharmaceutical industry enjoy the benefits of close ties to the government. There is no starker example than one championed by the domestic media and hailed by quarters of the international press.(Siddiqui 2020) Beximco took orders for, produced and sold the generic Remdesivir – a drug whose effectiveness in treating COVID-19 symptoms has been questioned by the WHO and independent medical experts (Wang, et al., 2020; Talukder, 2020) – at home (for US$77.00 per dose) and abroad. The government did not, however, hesitate to cite the WHO in withholding approval for the US$3.00 rapid antibody test developed by Gonoshasthaya Kendra at a time when there were only 1,732 RT-PCR kits available in the country – essentially using the WHO as cover for a decision born of nepotism and political animus (Ahasan, 2020). Moreover, hospitals affiliated to the Awami League, such as party member Mohammad Shahed’s Regent Hospital, have built a business of selling falsified COVID-19 certificates for up to US$ 59.00 per certificate, taking advantage of the clean bill of health criteria outlined by the state (Gettleman and Yasir, 2020). In other words, the IDA is precisely imperfect enough to pretend there is a plan when actually there is none, which falls in line with the laissez-faire despotism that rules Bangladesh.

Workers of the land

Cyclone Amphan, reaching Bangladesh on 20 May 2020, illustrated the importance of proper risk management. Bangladeshis were fearing the worst when weather warnings informed them of a severe cyclone approaching in the midst of the ongoing health crisis (Ellis-Peterson and Ratcliffe, 2020). However, as a country that is no stranger to extreme climate events, the 2012 Disaster Management Act (DMA) provided useful guidelines. The countless lives saved by efficient evacuation before Amphan made landfall owed to the DMA being followed. Two key differences between the DMA and the IDA are that the Prime Minister has sole authority to lead a response under the former, and her orders are both implemented by a larger national council (Section 4(2) of the DMA) and supplemented by sizeable regional committees in the affected regions (Section 4(5) of the DMA). The clear chain of command and identifiable resources foster timely action. Bangladesh’s familiarity with extreme climate events and their socio-political effects, even contributing to regime change in the past, has forced the government to overcome ts dysfunction and learn how to manage them. It is disingenuous to suggest that the same level of foresight is not possible for a disease outbreak since it is unforeseen. Bangladesh has experienced its fair share of epidemics and continues to suffer from annual outbreaks of dengue and other mosquito-borne diseases (Mamun, Misti, Griffiths and Gozal, 2019). Additionally, COVID-19 has had a hold on the country for several months, with no end in sight. There has been enough time to design and implement a comprehensive plan. The political will to do so has not been there.

A crisis being the great equaliser is a neoliberal fallacy, reinforcing and justifying inequality and injustice. Crises abide by the same classist hierarchies as the capitalist societies that deepen, and, often, create them. The poor and subjugated minorities are hit the hardest. The improved management of natural disasters has done little to empower or improve the welfare of affected populations over the years, leaving them vulnerable to unregulated capitalists and unaccountable governments.

Rebuilding after a flood or a cyclone lends itself to feel-good corporate social responsibility montages of distributing a few grains, second-hand clothes and blankets, of urban volunteers mollifying their consciences by nailing a corrugated tin sheet onto the wooden silhouette of a rural house. Such relief is essential, but it does not restore lives and livelihoods. Initially, the pandemic theater of COVID-19 featured photographs of dozens of elites and their subordinates, circulated in the mainstream and social media, dangling small bags of food above the emaciated hands of the destitute. (Tribune Desk, 2020b). But social responsibility has its limits.

By declaring a general holiday, the government removed any obligation the elite class had to participate in solving the developing crisis. The Awami League, heavily dependent on the elite to make Sheikh Hasina’s position permanent and comfortable, appease them as they do the military, to consolidate the foundations of its authoritarianism. Without any directives, employers were free to interpret a general holiday as they pleased (ALAP, 2020). They could both count the days of closure towards employees’ contractual paid and unpaid leave, or force employees to work without pay.

Any discussion of the dire state of employment rights in Bangladesh has to begin with an appraisal of the Labour Act 2006 (LA). The name of this statute is a misnomer, as it does not define what labour is and limits the definition of workers to the categories explicitly stated, excluding volunteers, informal workers and white-collar employees (Section 2(6) of the LA). There is no governing legislation for anyone other than workers as defined by the LA, resulting in terms of employment being unfairly weighted in favour of employers (ALAP, 2020). The problem is compounded further by the fact that 85% of Bangladesh’s employed workforce consists of informal workers who enjoy no protections since they are not recognised by the law.

|

|

Formally recognised workers operate under the constant threat of being relegated to an informal worker status by abusive employers in established industries such as agriculture, Big Garment, and migrant labour, which keep operations as informal and unstructured as possible. The doctrine of statutes being interpreted in favour of the vulnerable means little when the vulnerable party is not recognized by the statute, making access to justice non-existent. What little bargaining power employees have that is recognised by the LA is diminished by obstacles to justice enshrined in the Act. For instance, freedoms to organise, assemble, and protest are conditional rights at the discretion of employers (Section 176 of the LA). Dispute resolution is not an individual right and can only be pursued through representative committees (Section 205 of the LA), whose affiliation with employers make them instinctively reluctant to take action against them. The sixty-day time limit for judgments is not enforced as there are no consequences, leading cases to drag on an average of four years. (ALAP, 2020). The pandemic-induced closure to the judiciary can only cause further delays. But for the ingenuity of a few lawyers and likeminded judges, virtual courts would not have started operating in the limited capacity that they are (Akhter Imam & Associates, 2020).

Big Garment has mastered the art of ticking all the boxes without giving any power to the workers, thereby legalising abuse. At the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, the workers were forced into mass migration to their rural homes because their employment lacked fundamental safety nets (Kaizer, 2020). The government rushed to bail out the owners to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars in March rather than giving the money to the workers (Kashyap, 2020; Ellis-Petersen and Ahmed, 2020). Pleading poverty and absolving themselves of all responsibilities by passing the buck to foreign brands, Rubana Huq, the president of Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) and the physical embodiment of Big Garment – speaking for owners, workers, women, feminists, liberals, and poets everywhere – led an elitist propaganda charge to consolidate the owners’ fortunes. At that exact time, workers who had been laid off and had not been paid were walking hundreds of miles to their villages (Kaizer, 2020). Within days, they were forced to make the journey back on foot – when owners decided to interpret the general holiday as discretionary and reopened their factories (Alif, 2020) – thus travelling to and from the centres of the early outbreaks (The Economist, 2020). While mitigating the owners’ plight, Huq was wholly unsympathetic to the workers, denying allegations of exploitation, instead blaming the workers for causing the difficulties they were facing.

She insisted that workers were “dying to get back to work” (The Stream, 2020) to ward off poverty, and that poor people had a special resilience – a euphemism with historical exploitative connotations in the country –that would enable them to survive a mere disease (BGMEA, 2020). This audacious spin could not obscure the truth that the owners had amassed great wealth by exploiting and abusing workers and refusing to provide fundamental employment rights regarding safety and job and income security, knowing they had the full backing of the government. Where they should have been sounding the alarm about workers’ healthcare and financial needs, elite civil society leaders such as BRAC and the academic Mushfiq Mobarak were contracted by the government to find ways of supporting Huq’s desire to “open the economy” (Ekkator TV, 2020). They crafted and peddled a “lives versus livelihood” fallacy, to render the violation of human rights palatable (ibid.), disregarding the devastating effects of relaxing COVID-19 restrictions (MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis, 2020). The payoff was visibility – an opportunity to get closer to the corridors of power and benefit their own profiles and pet projects. State apologia from independently contracted apparatchiks well known in urban and international circles have added a veneer of respectability to the Awami League.

COVID-19 amplified the government’s usual unwavering support for Big Garment. The Minister of Finance repeatedly broadcast consecutive years of 8% economic growth in spite of the economy having ground to a halt (Star Online Report, 2020a), making it an Awami League diktat, requiring some artful accounting when the budget was announced in June 2020 (Ahsan, 2020). Big Garment accounts for 85% of Bangladesh’s exports (Latifee, 2016), and, following the decimation of the migrant labour industry by COVID-19 (Kashyap, 2020), its significance to a government desperate to revive the economic success narrative could not be overstated. Bangladesh’s economy has required diversification for a long time, but a post-pandemic economic recovery will rely entirely on the largest existing industries, given carte blanche by the government. By the time irregularities in paying salaries became commonplace (Alam, 2020) and the disease began to spread due to negligible monitoring and healthcare protocols (Ellis-Petersen and Ahmed, 2020), the successful reopening of the economy was the prevailing narrative. It reinstated the principles of workers being dispensable, the lives of the poor being worth nothing, and of the wants of the ruling and elite classes superseding the needs of everyone else. The rich have long been getting richer by making the poor poorer in Bangladesh; now the rich have a mandate to get richer by killing the poor.

Applying strict restrictions to public places is a fundamental part of any effective COVID-19 response, but places of work have presented an unsolvable problem for such policy initiatives. The LA’s definition of establishments catalogues what constitutes a place of work and what the protocols regarding them are, but it exempts public and government bodies and not-for-profit and religious entities (Section 1(4) of the LA). With money scarce, organisations have been taking advantage of this provision, directly contributing to the abuse of employees. To make matters worse, a 2013 amendment stated that all offices had to comply, but since the previous exemptions were not removed, this only added incongruity to the law and further undermined labour rights (Section 6 of the LA).

Digital dissent, actual assent

Fresh from its renewed popularity after leading protests against Narendra Modi’s unlawful citizenship reforms, Hefazat-e-Islam (Hefazat) pre-emptively declared its intentions to contest any decision to close religious institutions as COVID-19 cases were being confirmed in the capital, even before the government adopted any such measures (Hossain, 2020). This network of hard-line Islamist clerics has flourished under Awami League patronage, influencing state policy in return for reinforcing the party’s grip on power by shoring up its Salafi credentials. Where Hefazat leads, other Islamists follow, regardless of internal ideological differences.

|

|

Hefazat Demonstrations against secularism (Credit: Al-Jazeera) |

|

When the first COVID-19 death was reported in the country on 18 March 2020, Hefazat mobilised tens of thousands of its followers to hold a mass prayer gathering the day after – a full week before the start of the general holiday (Ng, 2020). Bangladeshis were pronounced more religious than Arabs when Saudi Arabia imposed restrictions on its places of worship, and Islamists demanded mosques remain open (Wyatt, 2020). Lacking the legal means and the political will to defy these calls, limiting the number of worshippers at mosques was amongst the last measures enacted, and neither prayers at mosques nor religious gatherings were strictly monitored or banned (Tribune Desk, 2020c). Additionally, Hefazat was rewarded with an extremely generous COVID-19 handout that was the envy of the truly vulnerable. (UNB, 2020b).

The Constitution has secularism as a founding principle (Section 12 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh) and Islam as the state religion (Section 2A of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh). This allows the Awami League to present Bangladesh as a secular, moderate Muslim country to an Anglophone world only too happy to accept this at face value, and simultaneously erode secularism by pandering to local Islamist majoritarianism.

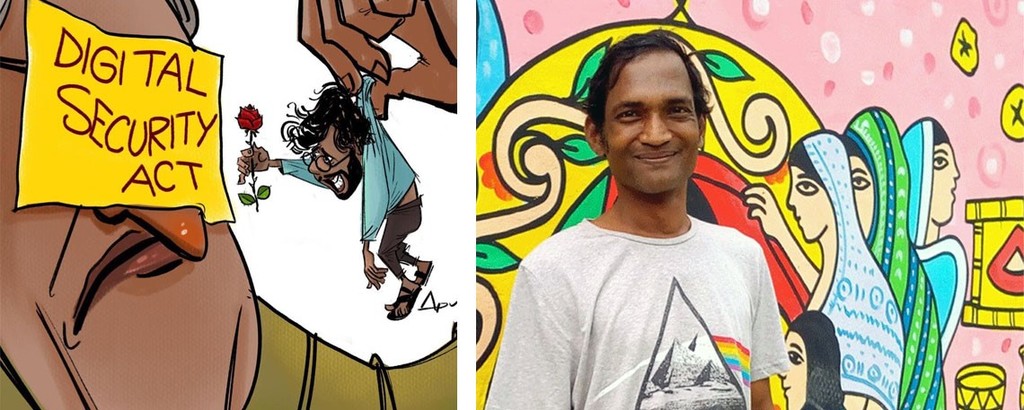

Those hurting religious sentiments – a weaponized accusation for Islamist majoritarianism and suppression of free speech – were soon targeted by the government. Concurrently, elite-establishment public intellectuals such as Imtiaz Ahmed and his son (for nepotism is rife in the intelligentsia too) Shakil Ahmed, invoked the spirit of 1971 and began to preach the gospel of positivity instead of negative remarks and rumours (Ahmed, I., 2020). Soon thereafter, Awami League loyalists filed lawsuits under the draconian Digital Security Act 2018 (DSA) against citizens engaged in rumour-mongering and bringing the nation into disrepute (Rabbi, 2020). From 1 March 2020 to 22 June 2020, a total of 89 cases were filed against 173 anti-state people (Article 19, 2020). A BRAC University academic involved with COVID-19 modelling was suspended for getting unfavourable results (Netra Report, 2020b). Criticising the lack of consideration for human life was as much of a crime as highlighting the evils of unbridled capitalism or the Awami League’s ineptitude (Human Rights Watch, 2020a). Words were not the only form of criminal expression, as arrested cartoonist Ahmed Kabir Kishore discovered (Human Rights Watch, 2020b; Reporters Without Borders, 2020). The DSA overcame national borders to extra-jurisdictionally charge people residing outside Bangladesh, asserting that Bangladeshi laws apply worldwide (Islam and Saad, 2020). Age was no barrier, as even a fifteen year-old minor who criticised Sheikh Hasina was arrested (Adams, 2020), nor was profession, as when doctors and garments workers were arrested for breaking their silence (Ahmed and Tusher, 2020). The absence of an absolute right to bail under the DSA facilitated the process of criminalising citizens exercising their freedoms of speech and expression (Star Online Report, 2020b). When card-carrying members of the Awami League misappropriated aid and funds, there was an increase in violence and prosecutions against those exposing such misconduct. (International Federation of Journalists, 2020). The Ministry of Information initiated a dedicated nationwide surveillance programme to identify COVID-19 rumours (Transparency International Bangladesh, 2020). Enforced disappearances kept pace with arrests under the DSA (Ahmed, K., 2020), which have exceeded 1,000 since the Act came into existence less than two years ago (Article 19, 2020). A woefully inadequate relief programme became an afterthought as the government diligently pursued a COVID-19 policy of denial, deflection, and dishonesty while criminalizing criticism.

|

|

Bangladesh’s healthcare system had been neglected for decades. Private clinics and hospitals vastly outnumber their public counterparts and are under no legal obligation to offer COVID-19 treatment (Vaidyanathan, 2020). Refusing treatment to patients suffering from a wide spectrum of diseases other than COVID-19 has become common practice in a country where revocation of medical and hospital licences is negligible (Mamun and Rahman, 2020). Private medical institutions conducting COVID-19 tests charge upwards of US$40.00 per test, while the government decided to end free testing, alleging that citizens were abusing the system. (ibid.). To date, of the alleged 14,000 beds available in COVID-19 designated hospitals for a population of over 160 million, 3,897 are occupied; patients have to overcome the difficulty of accessing healthcare and the pervasive social stigma of testing positive and getting treated. (DGHS, 2020). Hospitals severely lack trained doctors and nurses, safety protocols and adequate medical equipment and PPE (Transparency International Bangladesh, 2020). There is a total of 1,169 intensive care unit beds in Bangladesh, of which 432 are in public hospitals across the country, 112 of which were made available for COVID-19 patients (Maswood, 2020). There is one ventilator for every 100,000 people (ibid.; Save the Children, 2020). In terms of testing, a total of around 700,000 samples was collected as of 27 June 2020 – with a current weekly capacity of 100,000 sample collections and a daily testing rate of under 20,000 – making for some of the lowest testing rates and least effective testing systems worldwide (DGHS, 2020). There is evidence that the state has been less than forthcoming about the true extent of COVID-19 infections (Ganguly, 2020), and there are widespread reports of COVID-19 symptoms and deaths going undetected and unreported as the number of burials have increased manifold at cemeteries across the country, outstripping the official figures (Tribune Desk, 2020d). Officially there are nearly 150,000 total cases and over 1,800 deaths, but these figures are rising in a nation where the positive test-rate is an alarming 18.9% compared to 4.8% in the US and 2.1% in the UK (DGHS, 2020).

The so-called stimulus package is a loosely defined multibillion dollar loan package, dangling a proverbial noose in front of banks already collapsing under the weight of major loan defaulters like Salman F. Rahman and the richest of the Awami League (Riaz, 2020b; KPMG, 2020). Directors of Beximco related to Rahman, Sikder Group, and other scandal plagued government-affiliated corporations have been treated leniently and been granted special concessions (Abdullah, 2020). These members of the elite class have been able to escape the dire realities of COVID-19 in Bangladesh. Beyond isolating themselves into impregnable bubbles with self-imposed lockdowns and hospitals designated to solely treat them (TBS Report, 2020c), this elite managed to bypass travel restrictions and flee to safe havens abroad (Al Jazeera, 2020). Aid and relief have been all but forgotten as unemployment and poverty rises unabated (Riaz, 2020b), and a bumper harvest is the only thing that has staved off nationwide food shortages for the time being (Islam, 2020; Vaidyanathan, 2020). No one dares wonder out loud about the allocations set aside for the birth centenary celebrations. Such questions, along with investigations into, or criticisms of, the ruling elite, can land one in prison or worse. Frustrated by an inability to bully the invisible virus into submission, the Awami League continues to oppress the free citizens of Bangladesh as their main measure in countering COVID-19.

On a wing and a prayer

Give there is no cure or reliable treatment for COVID-19, it is relatively easy to make the case that there is no right way to deal with it. While COVID-19 is exposing systemic deficiencies familiar to Bangladeshis, it is being exploited to distract from government failures and safeguard the status quo. The story of the global pandemic in Bangladesh is the story of apathy against the backdrop of the breakdown of the rule of law, of pockets of resistance from conscientious citizens in defiance of state inaction, incompetence and malfeasance. The state’s failures are justified, normalised, trumpeted as successes, and then quickly forgotten.

An act of God crisis has been rendered a man-made disaster in Bangladesh. Perhaps fittingly, the centenary of the country’s first autocrat’s birth has become the year a disease exposed the Awami League as a vehicle of despotism and nepotism. The untouchable ruling and elite classes have flown away to a dreamscape bubble manufactured by the proletariat and constructed by the precariat, leaving behind the masses in a nightmarish reality. It took a global pandemic to bring the devastating, irreversible effects of these twin plagues to light. Beyond a point of no return, there is no miracle cure or vaccination for democracy in Bangladesh.

Bibliography

Abdullah, M. 2020. “The dramatic escape by Sikder brothers”, Dhaka Tribune, 29 May.

Adams, B. 2020. “Bangladesh Arrests Teenage Child for Criticizing Prime Minister”, Human Rights Watch, 26 June.

Ahmed, H. S. 2014. “Part-time peacekeepers”, Himal South Asian, 10 November.

Ahmed, I. 2020. “Overcoming the Covid-19 crisis”, The Daily Star, 30 April.

Ahmed, I., and Liton, S. 2020. “Health authorities let Bangladesh down in fight against coronavirus”, The Business Standard, 23 March.

Ahmed, K. 2020. “Bangladeshi journalist is jailed after mysterious 53-day disappearance”, The Guardian, 8 May.

Ahasan, N. 2020. “A $3 Covid-19 rapid kit by Bangladesh’s leading health centre is stuck in a bureaucratic quagmire”, Scroll.in, 7 May.

Ahmed, S., and Tusher, S. 2020. “Digital Security Act and the theocratic state-ocracy”, Shuddhashar, 1 June.

Ahsan, N. 2020. “Ambitious budget amidst a pandemic”, Dhaka Tribune, 12 June.

Akash, H. U, and Sarker, T. A. 2020. “People protest Modi’s upcoming Bangladesh visit”, Dhaka Tribune, March 2.

Akhter Imam & Associates. 2020. “ALAP – Legal Webinar Series, Discussion on Virtual Courts: Challenges and Prospects”, Akhter Imam & Associates.

Al Jazeera. 2020. “Coronavirus: travel restrictions, border shutdowns by country”, 3 June.

Alam, J. 2020. “Hundreds of Bangladeshi garment workers demand unpaid wages”, ABC News, 16 April.

ALAP. 2020 “Webinar: Rights of Workers and Employers during the COVID-19 Pandemic”, Academy of Law & Policy (ALAP).

Alif, A. 2020. “Who is to blame for RMG long march fiasco?” Dhaka Tribune, April 6.

Article 19. 2020. “Bangladesh: Alarming crackdown on freedom of expression during coronavirus pandemic”, Article 19, 19 May.

Bangladesh Labour Act. 2006. The Government of Bangladesh.

BBC News. 2007. “Troops enforce Bangladesh order”, BBC Online, 12 January.

bdnews24. 2020. “Saiful Alam made DGFI chief as five major generals get new duties in army shake-up”, bdnews24.com, 24 February.

BGMEA. 2020. “War Against Coronavirus”, on Facebook Live Video.

Daniyal, S. 2020. “Analysis: Has coronavirus given Dhaka an excuse to avoid the embarrassment of anti-Modi protests?” Scroll.in, 10 March.

DGHS. 2020. “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update”, Directorate General of Health Services, Bangladesh.

Dhaka Tribune. 2020. “Last Window to Tame the Beast”, on YouTube, 26 May.

Disaster Management Act 2012, Government of Bangladesh, Humanitarian Response.

Ekkator TV. 2020. “Stay at Home – Episode 7”, on YouTube, 20 April.

Ellis-Petersen, H., and Ahmed, R. 2020. “Bangladesh garment factories reopen despite coronavirus threat to workers”, The Guardian, 11 May.

Ellis-Petersen, H., and Ratcliffe, R. 2020. “Super-cyclone Amphan hits coast of India and Bangladesh”, The Guardian, 20 May.

Ganguly, M. 2020. “Bangladesh Should Listen to its Health Workers”, Human Rights Watch, June 21.

Gettleman, J., and Yasir, S. 2020. “Big Business in Bangladesh: Selling Fake Coronavirus Certificates”, New York Times, 16 July.

Government Gazette Archive. 2020. “Extraordinary Gazette of June 2020”, Bangladesh Government Press, 23 June.

Haider, S. 2020. “Coronavirus, CAA put pause on high-level visits”, The Hindu, 7 March.

Hill Voice. 2020. “Thousands of indigenous families of the country in food crisis due to corona pandemic”, Hill Voice, 12 April.

Himal Editors. 2020. “India’s crossborder crises, COVID-19 corruption, and more”, Himal South Asian, 26 June.

Hossain, I. 2020. “Social distancing, at the masjid too”, Prothom Alo English, 24 March.

Human Rights Watch. 2020a. “Bangladesh: New Arrests Stifle Free Speech”, Human Rights Watch, 14 February.

Human Rights Watch. 2020b. “Bangladesh: Mass Arrests Over Cartoons, Posts”, Human Rights Watch, May 7.

Huq, R. 2020. “Global brands must not abandon Bangladesh’s factory workers in the coronavirus crisis”, The Washington Post, April 18.

Imam, Ra. 2020. “At war with no ammo: Constitutional rights of healthcare workers”, The Daily Star, 18 April.

Imam, Re. 2020. “Urgent need for a COVID-19 Act 2020 in Bangladesh”, The Daily Star, 28 April.

Infectious Diseases (Prevention, Control and Elimination) Act 2020. Government of Bangladesh.

International Federation of Journalists. 2020. “Bangladesh: Politician charges media under Digital Security Act”, International Federation of Journalists, 22 April.

Islam, M. S. 2020. “Farmers expect good Boro yield but worry about lack of harvest workers”, Dhaka Tribune, April 11.

Islam, Z., and Saad, M. 2020. “Digital Security Act: 11 sued, two sent to jail”, The Daily Star, 7 May.

Kaizer, F. 2020. “From bustling streets to lockdown: Bangladesh and the UN mobilize to fight COVID-19: a UN Resident Coordinator blog”, UNDP Bangladesh, April 26.

Kashyap, A. 2020. “Protecting Garments Workers During COVID-19 Crisis”, Human Rights Watch, April 22.

Khokon, S. H. 2018. “General Aziz Ahmed named new Army Chief of Bangladesh”, India Today, June 18.

KPMG. 2020. “Government and institution measures in response to COVID-19”, KPMG International.

Latifee, E. H. 2016. “RMG sector towards a thriving future”, The Daily Star, 2 February.

Mamun, M. A., Misti, J. M., Griffiths, M.D., and Gozal, D. 2019. “The dengue epidemic in Bangladesh: risk factors and actionable items”, The Lancet, 394. Pp. 2,149-2,150.

Mamun, S. 2020. “Coronavirus: Bangladesh declares public holiday from March 26 to April 4”, Dhaka Tribune, March 23.

Mamun, S., and Rahman, M. 2020. “Govt to bear costs of private hospitals treating Covid-19 patients”, Dhaka Tribune, May 10.

Maswood, M. H. 2020. “Only 112 ICU beds for coronavirus patients in Bangladesh”, New Age, 8 April.

MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis. 2020. “Situation Report for COVID-19: Bangladesh, 2020-06-26”, Imperial College London, June 26.

Netra Report. 2020a. “Crackdown against critical voices”, Netra News, 7 May.

Netra Report. 2020b. “Researcher in trouble for co-authoring Bangladesh Covid-19 projections”, Netra News, 22 March.

Ng, K. 2020. “Coronavirus: Mass prayer gathering is held in Bangladesh to read ‘healing verses’ against Covid-19”, The Independent, 19 March.

Paul, R. 2020. “Bangladesh confirms its first three cases of coronavirus”, Reuters, 8 March.

Rabbi. 2020. “Upsurge in Digital Security Act cases during the Covid-19 pandemic”, Dhaka Tribune, 28 June.

Rabbi, A. R., and Rahman, M. 2020. “Covid-19: Police action during social distancing draws flak“, Dhaka Tribune, 27 March.

Rahman, M. 2020. “Govt in the dark over PPE requirement”, Dhaka Tribune, April 1.

Reporters Without Borders. 2020. “Bangladeshi journalists, cartoonist, arrested for Covid-19 coverage”, Reporters Without Borders, 14 May.

Riaz, A. 2020a. “A pandemic of persecution in Bangladesh”, Atlantic Council, 11 May.

Riaz, A. 2020b. “Bangladesh’s COVID-19 stimulus: Leaving the most vulnerable behind”, Atlantic Council, 8 April.

Save the Children. 2020. “Covid-19: Bangladesh has less than 2,000 ventilators serving a population of 165m, warns Save the Children”, 6 April.

Siddiqui, Z.. 2020. “Bangladesh’s Beximco to begin producing COVID-19 drug remdesivir” Reuters, May 5.

SOMOY TV. 2020. “Mujib Borsho celebration”, on YouTube, 17 March.

Star Online Report. 2020b. “Digital Security Act case: Court refuses to hear bail petition of Kajol”, The Daily Star, 22 June.

Star Online Reporter. 2020a. “Bangladesh could lose 1.1% of its GDP for coronavirus: finance minister”, The Daily Star, 25 March.

Talukder, R. K. 2020. “WHO advices against remdesivir, plasma therapy in treating Covid-19”, Dhaka Tribune, May 30.

TBS Report. 2020a. “People will always uphold Bangabandhu’s ideals: Hasina”, The Business Standard, 17 March.

TBS Report. 2020b. “Beximco exports 6.5 million PPE gowns to USA”, The Business Insider, 25 May.

TBS Report. 2020c. “Covid-19: Sheikh Russel Gastroliver Hospital to treat VIPs, diplomats”, The Business Standard, 22 April.

The Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

The Daily Star Law Desk. 2020. “The laws relating to communicable diseases”, The Daily Star, 14 April.

The Economist. 2007. “The coup that dare not speak its name”, The Economist, 18 January.

The Economist. 2020. “Covid-19 infections are rising fast in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan”, The Economist, June 6.

The Stream. 2020. “Coronavirus: Is Bangladesh putting its economy before people?”, Al Jazeera, 5 May.

Transparency International. 2020. “Corruption and the Coronavirus”, Transparency International, 18 March.

Transparency International Bangladesh. 2020. “Governance Challenges in Tackling Corona Virus”, Transparency International Bangladesh, 15 June.

Tribune Desk. 2020a. “Bangladesh observes Independence Day amid shutdown”, Dhaka Tribune, March 26.

Tribune Desk. 2020b. “Coronavirus: Researchers ponder why US, Europe are harder hit than Asia”, Dhaka Tribune, May 31.

Tribune Desk. 2020c. “Coronavirus: Mosque attendance during Jumma prayer falls”, Dhaka Tribune, March 27.

Tribune Desk. 2020d. “Burials in Dhaka rose by a third in May”, Dhaka Tribune, June 10.

UNB. 2020a. “Don’t hoard essentials, we have enough stocks: PM”, The Daily Star, 21 March.

UNB. 2020b. “Financial aid for all mosques, 7,000 more Qawmi Madrasas before Eid: PM”, The Business Standard, 14 May.

Vaidyanathan, R. 2020. “Bangladesh fears a coronavirus crisis as case numbers rise”, BBC Online, 16 June.

Wang, Y, et al. 2020. “Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial”, The Lancet, 395(10,236). Pp. 1,569-1,578.

Wyatt, T. 2020. “Coronavirus: More than 100,000 defy lockdown and gather for funeral in Bangladesh”, The Independent, 20 April.