Abstract: As of 30 June 2020, 14,046 COVID-19 positive cases have been confirmed in Nepal out of around 233,000 tests administered since January. So far, only 30 people have died of the coronavirus – a small number compared to worldwide trends. After the lockdown was eased on 14 June, the number of positive cases has spiked. An atmosphere of anxiety looms large over a spike in COVID-19 infections and possible deaths, and along with the pandemic, people fear hunger, inefficient government response, and the possibility of dystopia in the long run. Amidst this challenging time, popular protest and community solidarity have worked together with local government to provide some hope.

Imagining “Corona-Free” Paradise

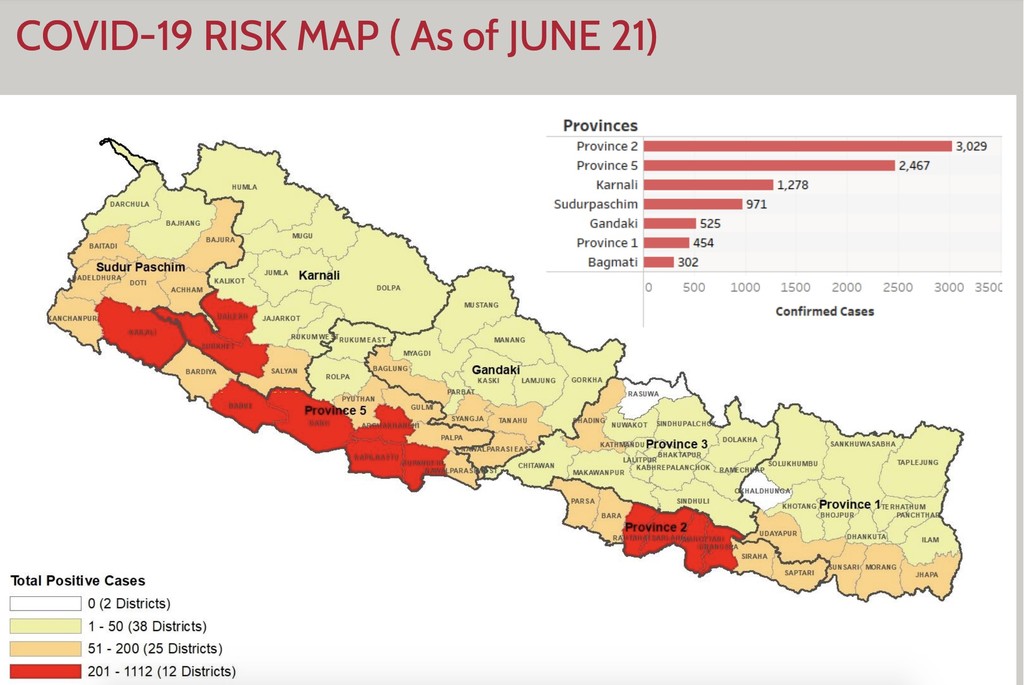

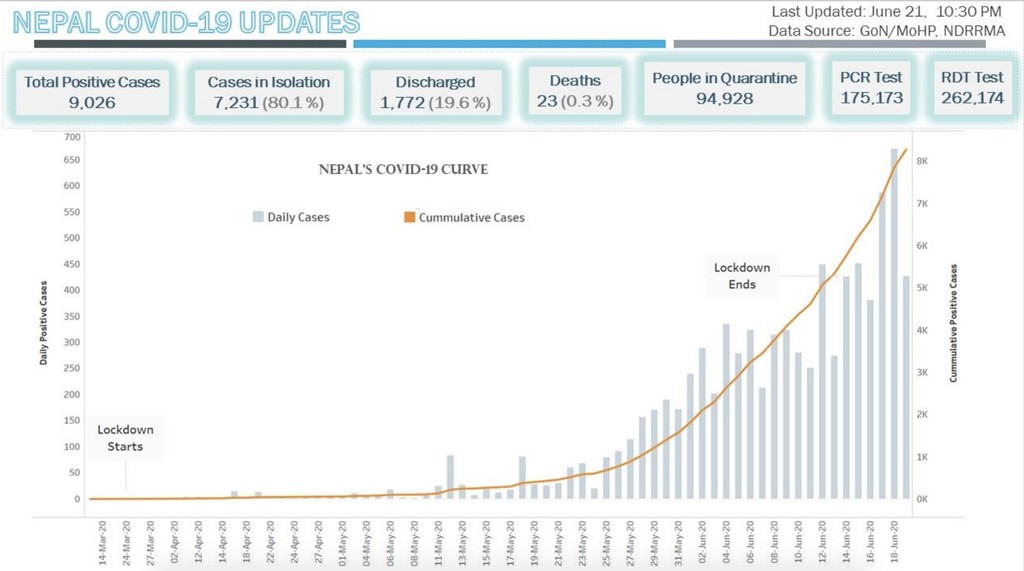

As of 30 June 2020, 14,046 COVID-19 positive cases have been confirmed in Nepal out of around 233,000 administered tests since January. So far, only 30 people have died of the coronavirus – a small number compared to worldwide trends. Nepal ranks fourth for the number of cases among South Asian countries, following India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh (Ministry of Health and Population, 2020). The first positive case in Nepal was confirmed on January 23, 2020: a 31-year old student who had returned from Wuhan, China. Nepal went into lockdown from 24 March and until the end of May, the number of cases remained under 1,000. Since then, the number of positive cases has surged significantly, accelerating especially after the easing of the lockdown from 14 June 2020. According to the Ministry of Health, 94 percent of positive cases are from returnees from outside the country (Poudel, 2020), mostly laborers returning from India. This indicates that community transmission has just started, and the worst is yet to come. The population, especially those belonging to marginalized classes, castes, and ethnic groups, have lived with hardship and anxiety during the past three months of lockdown. As more migrant workers lose their jobs and are expected to return home from other countries, the atmosphere of anxiety looms large over a spike in COVID-19 infections and possible deaths. With the pandemic, people fear hunger, inefficient and undemocratic government, and the possibility of dystopia in the long run. Amidst this challenging time, popular protest and community solidarity have worked together with local government to provide some hope.

The first positive case passed essentially unnoticed, and the patient recovered. But it was a warning sign. Instead of taking the virus seriously from the start, government officials adopted a wishful outlook that the coronavirus would not arrive in Nepal. Ironically, this wishful thinking was happening around the time when COVID-19 cases in Italy were rising rapidly. On February 19, Minister for Culture, Tourism, and Civil Aviation Yogesh Bhattarai explained that he instructed his staff to prepare promotional materials in English, Chinese, and Hindi languages to inform the world that Nepal is a “coronavirus-free” zone (Subedi, 2020). This was done with the intention of luring foreign tourists. The government had touted 2020 as the “Visit Nepal” year, aiming to bring in two million tourists by presenting Nepal as an exotic and safe Shangri-la, a paradise in the Himalayas. Only when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on 11 March did the government of Nepal and Kathmandu’s intelligentsia come to understand how serious the situation was. The government then declared a lockdown of the country starting on 24th March as its best option to contain the coronavirus outbreak.

|

|

Season of Panic and Plight

The government formed a high-level committee led by Deputy Prime Minister and Defense Minister Ishwar Pokhrel for the prevention and control of COVID-19 which issued an eight-point order to prohibit movement outside of the home, except in cases of emergency or to get essential foodstuffs, beginning from 6 AM on Tuesday, 24 March (Pradhan, 2020). It was virtually a curfew, as all public and private vehicles were barred except those with prior permission. All business, service, and construction work were halted. A season of panic and difficulty began for the marginalized.

A new vocabulary became public vernacular with COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdown. The government communique evoked war-like imagery, with the coronavirus presented as an invisible enemy that the state would defeat to save the people. The public could not help but notice that it was the Defense Minister presiding over the high-level committee coordinating the COVID-19 response rather than the Health Minister.

The concept of lockdown itself was new, one with which the ordinary people of Nepal have no prior experience. The only similar events are the Nepal bandh, or general strikes, where the agitating party would call for the closure of shops, educational institutions, and banning of all vehicle movements. However, unlike during lockdown, the groups organizing the Nepal bandh would also stage street protests, sometimes coupled with considerable vandalism. The lockdown looked like a curfew to some because security forces were deployed to keep the people inside their houses, but it was different than curfew because there was no imminent threat to the government which required curfew-like restrictions. People were told to wash their hands, maintain social distance, wear a face mask, and stay home for their own safety.

It took a few days to come to terms with what it meant to be living in lockdown, which for many felt like self-imprisonment. Some people went out on the streets to find out what lockdown looked like from the outside. Many more had to venture out to obtain the necessities of living. Police would interrogate them and make them stand on the spot for two hours for violating lockdown, but for the majority of the poor who lived in crowded shantytowns or cramped rented rooms, staying inside at all times was simply impossible. Within a few weeks, people started to panic.

|

|

Elite intelligentsia, opinion-makers, and the mainstream media in Kathmandu adopted a new vocabulary associated with coronavirus in their day-to-day tasks. Many of the concepts, including the coronavirus itself, had been novel even to the West and China, the original epicenter. The notions of “lockdown,” “social distancing,” “quarantine,” and “isolation” became common in public discourse. In Nepal some debated the incompatibility of these terms with the local sociocultural context while others tried to translate the terms in vernacular language for easier comprehension. Some scholars argued against the concept of social distancing, as it was something caste-ridden Nepal wanted to get rid of. They preferred to call it “physical distancing,” as social distancing explicitly echoed practices of hierarchy and untouchability (Dhakal, 2020). This is indeed the sad reality of living in Nepal. Unfortunately, whether one calls it social or physical, in a situation where half a dozen people have to share one room, distancing is out of the question. Other media giants wanted to translate the word “lockdown” in the Nepali language, proposing words such as banda-bandi roughly meaning closedown or ghar-bandi or lockdown in house. I wanted to propose ghera-bandi, which is roughly similar to the military term encirclement – used in this context to mean ordinary people surrounded by government forces in such a way that they are incapable of carrying on with their lives, and are left with no choice but to protest collectively against the government’s pandemic countermeasures.

Migrant laborers in Kathmandu found themselves without jobs and without time to plan for their next move when the lockdown was suddenly announced. They were not yet aware of what exactly the coronavirus was, nor how they could protect themselves from it; they only knew that it was dangerous. Yet perhaps even more so than the then invisible and unknown virus, they were scared of the prospects of arranging food, gas to cook with, and finding money for rent. The government had given no indication as to when the lockdown would finally be lifted. As the days passed with continuous extensions, anxieties mounted exponentially. People started to pack their things and walk back to their villages. The journeys were arduous; some people made more than a 500 kilometer-walk, from Kathmandu to Jhapa, or from Solokhumbu to Kailali district. The exodus was reminiscent of scenes of refugees fleeing from war zones, with women and children on the roads without food, water, or a place to spend the night. As they walked along the highways, police harassed and forced them into detours in darkened jungles. Estimates say that about 200,000 labor migrants left Kathmandu (Prasai, 2020). The mass departures continued for around a month, lasting until the end of April. In the meantime, the middle class living in Kathamandu would write in their lockdown diaries of how they passed the time as if it were a holiday, complete with barbecues, as others attended Zoom meetings, while the rich entertained themselves in casinos. The coronavirus experience turned out to be a class phenomenon.

|

Wage workers from Bardiya, Kailali and Kanchanpur returning home by foot from Kathmandu after the government imposed lockdown (Photo: Hemanta Shrestha) |

Stranded at the Border and in Quarantine

There are an estimated two million Nepalis in India, most working as low wage laborers in occupations ranging from security guards to cooks, waiters, porters, and laborers. After Prime Minister Narendra Modi imposed a complete lockdown in India for three weeks beginning March 24 (Banaji, 2020), Nepali workers were left without jobs and without a way to return home. Thousands began to walk. When the Indian government eased the lockdown, they rushed aboard buses, trucks, and vans to return to their villages in Nepal (Hashim, 2020). Local officials in border-towns estimated arrivals of around 2,000 each day. Unfortunately, they were denied entry to Nepal, as the government had closed the border in March. They gathered along border points in the south and the towns across the fierce Himalayan river Mahakali – the natural border between the two countries in the west – and remained there, stranded (Badu, 2020). The anxiety of not being able to reach family and fear of coronavirus death led some to swim across the river, only to get arrested by Nepali police.

When the government decided to let the migrants re-enter the country in mid-April, they were required to stay in quarantine for 14 days. The Health Ministry in Nepal asked local government bodies to set up places for quarantine – this was an important step in containing the virus before it could spread. Local governments erected quarantine tents in the border villages. As the schools were closed for an indefinite period due to COVID-19, the government later decided to open up space for quarantine in school buildings, and soon all of these newly set up quarantine centers were crowded with people. There were no toilets or bathrooms to properly attend to hygiene, nor did the quarantined have access to proper food and drink. Testing took a long time, sometimes as long as a month, before results from the swab samples were available. With the summer heat, people began to get sick, and those who had already been infected with coronavirus transmitted it to others. The quarantine centers ended up becoming centers for COVID-19 transmission. In the ordinary peoples’ minds, quarantine resembled prison. Those who were rebellious ignored quarantine measures. Thousands of others escaped to reach their homes directly. Local governments felt helpless as they said it would be impossible to meet the World Health Organization (WHO) standard of quarantine management given the limited budget, human resources, and capacity (Rai, 2020). Contact tracing was beyond their capacity.

Fear, Stigma, and Intolerance

Fearing transmission, residents did not want to have quarantine centers placed near their towns; people sought to keep their distance from others. In the midst of uncertainty, everyone became a suspect asymptomatic coronavirus carrier. The villages in the hills reenacted past practices of putting barriers at the entrances to keep away epidemics such as cholera, smallpox, chickenpox, and others. In Kathmandu, residents put blockades in the streets to prevent outsiders from entry. All markets, hotels, restaurants, airports, and transport were closed except those shops selling essential goods. I used to buy vegetables from a small grocery that opened during the lockdown in the morning hours, but on the morning of May 27, I learned that the owner had also decided to close shop. He told me “I have to travel to get vegetables to Kalimati. I used a scooter to carry them. Now, the police will not allow me to drive the scooter. It is too difficult to get driving permission from the administration for people like me. I thought, it is even more important to protect myself. Who knows how and when coronavirus might enter into my body if I continue to work.” Fear ran deep in individuals, in villages and towns and cities. The coronavirus response was suspicion, lockdown, and separation.

The dangers of stigma against the infected remain a major concern. It was especially worrisome when a national daily released news in March with a sensational headline calling a 19-year-old female student returning from France a potential “super spreader” (Shrestha, 2020). People stopped visiting coronavirus patients in hospitals or even attending funerals for the victims. Whether it was stigma or fear, nonattendance of relatives, kin, and even family members at the funerals of coronavirus victims reveals the degree of damage inflicted on the social fabric of Nepal (The Himalayan Times, 2020). In Pokhara, residents protested against the decision by the government authorities to bury coronavirus infected bodies on the banks of the Seti River. Police fired eight rounds to disperse the crowd (Koirala, 2020). In April, men from the Islamic organization Tablighi Jamaat who were living in a mosque for religious instruction tested positive in the southern towns of Birgunj and Udayapur. Out of the 13 who tested positive in Udayapur, 11 were visitors from India. Unfortunately, social media took to portraying the whole of the Muslim community as spreaders of the virus. Muslims, a small minority in Nepal, have been marked a target of ostracism and discrimination (Sijapati, 2020).

Faltering COVID-19 Response of the Government

The solution recommended by health experts was efficient testing, tracing, and isolation of the infected. However, since there was no COVID-19 testing equipment in Nepal, for the initial several weeks until early May, swab samples were sent to Hong Kong for testing. Now, there are 22 locations where PCR (or swab) tests can be done, with four in the capital city of Kathmandu. This is an extremely small number for a population of 28 million if the country is to carry out extensive testing, not to mention the problems presented by the long wait for test results. During the early phase, the government used rapid-diagnostic tests (RDTs), but the results turned out to be unreliable. Nepal has a weak healthcare system to begin with, and only major hospitals in the capital and provincial hospitals have the minimum facilities required for treatment of COVID-19 infected patients. Furthermore, the lack of adequate personal protective equipment for health workers on the frontlines is still an issue.

|

|

The government’s failure to effectively handle COVID-19 led to wide public discontent. This discontent was further fueled by a scandalous incident regarding the contracting of the Omni Group for the procurement of medical equipment and materials needed to control the coronavirus. It turned out that not only were the prices exorbitantly high, but the materials purchased were of poor quality (My Republica 2020). While the public was angered by the possibility of corruption at such a dire time, the government reported that they had already spent US$ 82 million of taxpayers’ money on the COVID-19 response.

Prime Minister Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli was not ready to take responsibility for the government’s failures. Instead, he downplayed COVID-19 and blatantly spread misinformation to the public. On June 19, addressing the National Assembly, he said that “Corona is like the flu. In case it is contracted: sneeze, drink hot water, and the virus will be warded off” (Pandey, 2020). Rather than focusing on the issues of the impending pandemic, unemployment, and plight of the marginalized, he tried to distract the public by resorting to inflammatory nationalistic rhetoric, such as asserting Nepali claims to a boundary also claimed by India. He has also taken further steps to curtail civic freedoms and to control the media in a series of autocratic moves. He is known for his divisiveness and disdain for the country’s disenfranchised population of indigenous peoples, Madhesi, Dalits, women, and minorities – and he labels those who question him “enemies” of the elected two-thirds majority government he heads. However, with his growing unpopularity, he is now being asked to step down even by those within his party. Subsequently, he abruptly prorogued the Parliamentary session on 1st July. He appears to be exploiting this COVID-19 crisis to consolidate his power, just as the devastating 2015 earthquake was used as an opportunity to get a controversial constitution endorsed, paving his way to the top. (Rai, 2020).

Protest and Community Solidarity as Hope

Lockdown and coronavirus heightened anxiety and deepened fear among the people of Nepal. This fear caused a rupture in the social fabric of the nation. Gloomy prognosis of unemployment and economic distress for the coming months and years generated panic. During the 88 days of lockdown, lasting from March 21 to June 20, 1,498 people committed suicide. The coronavirus and its traumatizing aftermath have exacerbated psychological, economic, and social stress, causing a surge in suicides (Sapkota, 2020). Moreover, the government’s inept crisis response, their disregard for the historically underprivileged, and undemocratic tendencies aggravated anxieties about the danger of dystopia and political conflict. Memories of the brutal civil war (1996-2006) still cast a dark cloud over Nepal in 2020. One has to wonder where hope might be found in this distressing scenario.

I see peoples’ protests and community solidarity as two key, necessary signs of hope. The Nepali youth have staged peaceful protests in the capital throughout June. A demonstration began outside the residence of Prime Minister Oli’s, demanding wider PCR tests, better management of quarantine centers, and the end of misuse of taxpayers’ money (Gill, & Sapkota, 2020). The demonstrators’ placards proclaiming: “Enough is Enough” convey the frustration that many Nepalis feel about the government.

I also place hope in communities’ spirits of solidarity and compassion, as this has been a key source of resilience in survival and recovery from the disastrous 2015 earthquake. After the lockdown was eased on June 20, I visited a village in the Roshi rural municipality of the Kavre district, making sure that I adhered to the rules of social distancing, mask-wearing, and hand washing. From the conversations I had with the people, I realized that while the community is anxious about the uncertain situation presented by the global pandemic, they are also dedicated to community solidarity and do what they can to extend support to one another. As soon as the lockdown was imposed, families called back their relatives working in cities. With the return of young people to villages, the atmosphere in these places revived somewhat, regaining a welcome vibrancy. They plowed some of the abandoned terraces for maize and vegetable cultivation and village religious rituals continued with necessary precautions. When I visited the village, road construction was ongoing. Now they have restricted interaction with outsiders, but they are confident that they can still manage to support the relatives yet to return from abroad and are ready to welcome them back into the community.

|

Road construction continues amidst pandemic in rural Nepal (Photo: Mukta Tamang) |

The community also praised the role played by their local government during the lockdown. Being a non-border municipality in the mid-hills region, they face relatively less risk than other villages might, but since one of the highways linking Kathmandu and eastern Tarai runs through this municipality, it remains vulnerable to those transiting. Many migrant workers walked along this highway to eastern districts during the lockdown. The Roshi municipality, of its own volition, provided food to travelers and escorted them to the border of the neighboring municipality. This was helpful not only for those walking, but also for the residents in order to prevent further contact. The local government set up a quarantine center in the local school where dozens of people who returned from India were isolated. So far, three people tested positive in this municipality. All of them are in the process of recovery. This goes to show that if the local authority is empowered to work in solidarity with their community, the coronavirus may be successfully contained, even if the national government is not up to the job.

References

Aryal, A. 2020. ‘Thousands of Nepalis without food or shelter await entrance at the Karnali border’, The Kathmandu Post, 26 May.

Badu, M. 2020. ‘Nepalis are swimming across the Mahakali to get home’, The Kathmandu Post, 30 March.

Banaji, M. 2020. ‘What effects has the lockdown had on the evolution of Covid-19 in India?’ Scril.in, 27 May.

Dhakal, S. 2020. ‘Samajik hoina, bhautik duri [Not social, physical distance]’. Kantipur, 18 April.

Gill, P., Sapkota, J.R. 2020. ‘COVID-19: Nepal in Crisis’, The Diplomat, 29 June.

Hashim, A. 2020. ‘The ticking time bomb of Nepal’s returning migrant workers’ Aljazeera, 10 June.

Koirala, B. 2000. ‘One hurt as locals clash with police protesting burial of coronavirus-infected body’, The Himalayan Times, 25 June.

Kumar, P. 2020. ‘COVID-19 Updates and Risk Mapping’, Unpublished presentation based on Ministry of Health and Population, the Government of Nepal.

Lohani, S.P. 2020. ‘COVID-19 May Magnify Suicide Rates,’ The Rising Nepal, 10 May. Accessed June 10, 2020.

Ministry of Health and Population. 2020. ‘Health Sector Response to COVID-19‘. Accessed 2 July 2020.

My Republica. 2020. ‘Feel some shame: Corruption in the time of crisis’, My Republica, 2 April.

Pandey, P. 2020. ‘Oli continues to downplay Covid-19 and propagate home remedies, earning ridicule on social media’, The Kathmandu Post, 19 June.

Poudel, A. 2020. ‘Six percent of Covid-19 cases are from communities, but no community transmission yet, Health Ministry says’. The Kathmandu Post, 2 July.

Pradhan, T.P. 2020. ‘Nepal goes under lockdown for a week starting 6am Tuesday’, The Kathmandu Post, 23 March.

Pradhan, T.R. 2020. ‘A cornered Oli prorogues the House and considers splitting the ruling party’, The Kathmandu Post, 3 July.

Prasai, S. 2020. ‘The Day the Workers Started Walking Home’, The Asia Foundation, 13 May.

Rai, D. 2020. ‘How Oli destroyed Nepal’s democratic machinery to serve his own ends’, The Record, 3 July.

Rai, N. 2020. ‘Quarantine guidelines impossible to meet: local governments’, Nepali Times, 7 June.

Sapkota, J, 2020. Korona Trasko asar [Effect of Corona Fear]. Kantipur, 29 June.

Shrestha, P. 2020. ‘Memoirs of the ‘Super-Spreader’, Setopati: Blog, 7 July.

Sijapati, A. 2020. ‘Nepal’s Muslims face stigma after COVID-19 tests’, The Nepali Times, 4 May.

Subedi, K. 2020. ‘Nepal is safe for tourists as it is free from coronavirus: Minister Bhattarai’, My Republica, 19 February.

The Himalayan Times. 2000. ‘No one attends funeral of coronavirus victim’, The Himalayan Times, 18 June.