Abstract: Sri Lanka’s first confirmed coronavirus cases of a foreigner and a local took place on 27 January and 10 March respectively. Upon prematurely dissolving the Parliament, the country’s attention was on holding an election on 25 April to further consolidate the power in the legislature riding on the victory at the Presidential Polls in November 2019. All were gearing up for a tough electoral battle. This was also the season of school cricket battles – a Sri Lankan preoccupation. While the number of infected cases as well as deaths gradually increased, the response to the pandemic was an embellishment of public health, politics and cricket within a quasi-democratic vacuum.

Context and Background

It was in the very end of December 2019 that the government in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province in China, officially confirmed that its health authorities were treating dozens of cases caused by a new coronavirus, now known as COVID-19. Japan, South Korea, and Thailand soon thereafter identified cases of people affected by the new coronavirus, and together with the World Health Organization, acted quickly to assess the situation and introduce stringent precautions to contain the pandemic.

In Sri Lanka, however, the month of December was a time of rest after a long, drawn out presidential election that had ended in the second half of November 2019. Gotabhaya Rajapaksa, a lieutenant colonel of the Sri Lankan Army from 1972-1992, and Secretary of Defense from 2005-2014, emerged as the victor in the presidential election, though it was no easy feat. While he had the advantage of being the brother of Mahinda Rajapaksa, who served as president from 2005 to 2014, Gotabhaya Rajapaksa (hereinafter called GR) faced two main challenges that put his candidacy at risk: his dual citizenship, and a court case in the US state of California. According to a constitutional amendment made in 2015, dual citizenship disqualified anyone from running for election or holding public office in Sri Lanka. In 1993, GR had left the Sri Lankan Army prior to his retirement on medical grounds to migrate to the United States, where he lived until 2005. In 2003, he applied for and became a citizen of the US, renouncing his Sri Lankan citizenship. Only two years later though, he re-applied for Sri Lankan citizenship while retaining his US citizenship to assume duties as Secretary of Defense under the presidency of his brother, Mahinda Rajapaksa (hereinafter called MR).

In the run up to the presidential election, GR claimed that he had renounced his US citizenship, but this was challenged in the Supreme Court by two prominent civil society activists. His second challenge involved a case filed in a California State Court by the daughter of a prominent newspaper editor who was murdered at the time GR was the Secretary of Defense. The daughter alleged that GR was responsible for her father’s murder. Just weeks before the election, both the California State Court and the Sri Lankan Supreme Court ruled in favor of GR, opening the door for him to be elected. While he also had a host of other court cases ranging from misappropriation of state funds to bribery involving military procurement, these cases dragged on for months as GR’s lawyers claimed that he was undergoing medical treatment in Singapore. The cases were still pending when he was elected president, but were withdrawn following his election since the president enjoys legal immunity.

|

President Gotobhaya Rajapaksa (left) and former President Mahinda Rajapaksa |

GR’s victory is considered significant as he was not dependent on the so-called minority votes of the Muslim and Tamil constituencies. This is the first time a president has been elected solely on the basis of winning overwhelming Sinhala-Buddhist support. GR’s campaign, grounded in Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism, capitalized on the backlash to the Easter Sunday bombings that killed 296 people in April of 2019 carried out by radical Muslim groups. The Rajapaksa dynasty is known to be tough on security issues, having ended the nation’s long civil war in 2009 and were thus seen to offer strong leadership to quell extremist violence. (Asia Times, 2020). While there was popular jubilation among the Sinhala-Buddhist majority over GR’s victory, GR’s inner circle was focusing on how he could consolidate his power. His victory had clear limitations and constraints, the first being an almost hung Parliament. The second was the fact that sweeping executive powers vested in the presidential office had been rescinded by a constitutional amendment initiated by the government that ruled from 2015 until 2019. With the victory of GR in November 2019, the then prime minister and cabinet resigned, paving the way for GR to appoint his loyalists. However, he lacked a working majority in Parliament. President GR and his loyalists openly expressed displeasure at Constitutional restrictions on executive powers they saw as obstacles to fulfilling his election promises. The 19th Amendment trimmed executive powers and established independent commissions, such as the Election Commission and Police Commission, to check the president’s power. Gaining a two-thirds parliamentary majority for the president’s party was deemed essential to undo the restrictive revisions to the Constitution. Hence, there was an urgency to holding general elections in order to ride the wave of President GR’s November victory. It was at this time with the advent of major socio-political change that the new coronavirus made its first appearance towards the end of January 2020.

COVID-19 hits Sri Lanka

|

The government imposed a 52-day curfew (Sri Lanka’s modality of lockdown) between 20 March and 10 May. The first confirmed case of coronavirus was reported in Sri Lanka on 27 January. The patient was a 44-year-old Chinese woman from Hubei Province who was visiting Sri Lanka. She was immediately admitted to a local hospital, underwent treatment, and was discharged on 19 February, complete with a ceremony and photo-op in which the health minister offered flowers to and kissed the recovered patient. In the meantime, the president dissolved the Parliament on 2 March, calling for snap elections six months early. The elections were to be held on 25 April, but only a day later, the first case involving a person of Sri Lankan origin was reported in Italy on 3 March. One week later on 10 March, the first local case was reported: a tourist guide who had led a group of Italian tourists. Both the Chinese woman and the tourist guide were treated at the so-called “IDH,” or Infectious Disease Hospital, which later came to be known as the National Institute of Infectious Diseases. It is considered a high-service level hospital focused on infection control, HIV, and other infectious diseases. Quarantine centers were also set up by the Army in their facilities in Diyatalawa and Nandakadu.

A 40-member “Presidential Task Force to Coordinate and Monitor the Delivery of Continuous Services for the Sustenance of Overall Community Life” was formed under Basil Rajapaksa, another brother of President GR’s. In mid-March, a “National Operation Center” was tasked with curbing the spread of COVID-19, with the Army Chief appointed at its head. The Center was mandated to coordinate preventive and management measures to ensure that healthcare and other services would be well equipped to serve the general public during the outbreak period. The mandates of these two structures were vague and lacked clarity regarding the division of labour. The legitimacy of introducing these new structures while existing structures were not being used drew heavy criticism (Center for Policy Alternatives, 2020).

Despite some unease over COVID-19 strategies, the dissolution of the Parliament and call for elections on 25 April created a distraction that put all of Sri Lanka in election mode. Sri Lankans’ public awareness regarding the impending danger of the virus that had already begun spreading across Asia and Europe was rather low at the time. Additionally, Colombo, the administrative and commercial capital of Sri Lanka, was preoccupied with planning for an important annual festivity that would take place in March: cricket.

Cricket: The initial coronavirus breakthrough?

While political parties and their supporters were busy preparing for the upcoming election, it was also the beginning of cricket season. Every March, the so-called ‘big matches’ between leading schools are played. These big matches, especially those played between the elite and prestigious schools in Colombo that produce the ruling political class, are something of a social sensation in Sri Lanka. These cricket matches take place over the span of two to three days, attracting around 10,000 spectators, usually students of the schools, parents, alumni, and well-connected families. Some alumni fly all the way from Europe, Australia, and North America just to watch the matches and attend the festivities. President GR himself attended a big match in support of his alma mater in the first week of March, his presence garnering a great deal of media attention. However, in the weeks soon after, the outbreak of coronavirus in Sri Lanka became more serious. Public criticism gradually mounted, and the government was accused of not imposing rules to curb large public gatherings, such as those at cricket matches. In response, the president lamented that the big match between Royal College and St. Thomas’ College (10-12 March) was played despite his objections. These two prestigious schools had produced the leadership of the country in its first five decades of independence. They boast that their annual cricket match has been a continually undisrupted tradition for 134 consecutive years, spanning two world wars and many domestic upheavals such as insurgencies, plagues, natural disasters, and a three decade-long civil war. However, the president’s ‘lament’ was surprising, as his reputation and track record from his time as defense secretary had gained him notoriety as a tough task master whose directives are implemented without question. However, the influence and power of the two elite schools in question should not to be underestimated. As they had produced the prime ministers and presidents of Sri Lanka in the first five decades following independence, they represent an opposing faction to that of the Rajapaksas. The trend of their alumni gaining office changed when President GR’s brother was elected in 2005. The Rajapaksas do not represent the Colombo elite; they are from the southern part of the country. To some extent, Sri Lanka’s pre-occupation with these big matches and elite private schools is representative of the social gulf between the urban “refined” and the rural “unsophisticated” which, in crude popular terms, are categorized as ‘toyyo’ and ‘bayyo’. The Rajapaksas were able to create a new political space by emphasizing nationalism and security to gain the votes of the Sinhalese-Buddhists, while ignoring the concerns of minority Muslims and Tamils. Thus, the entwining of political discourse and cricket in the initial weeks of COVID-19 spread was directly related to socio-political undercurrents that would continue to affect the course of countermeasures in Sri Lanka.

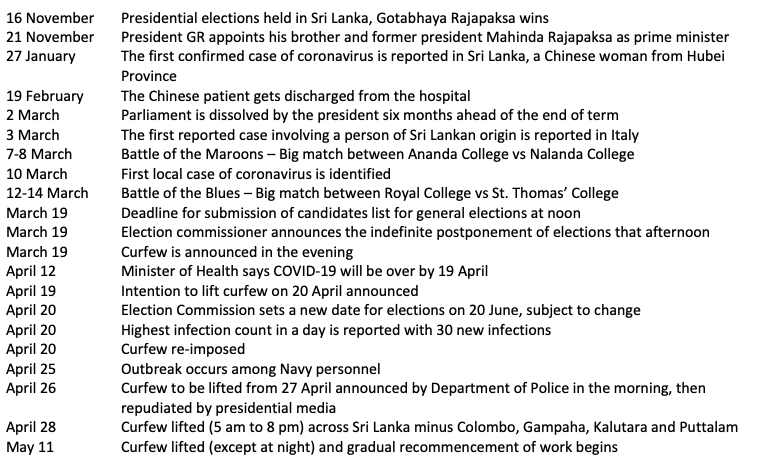

Chronology of Events

|

Elections as the key consideration

While the numbers of affected people were gradually rising in the third week of March, there were still no concrete measures introduced by the interim government (in the context of a dissolved Parliament) and the president. This passivity is ascribed to the desire of the president and his party to hold elections in April. On television, the health minister mentioned that she did not see any need to introduce stringent rules to curb the spread of the virus since the situation was not that bad and that they would go ahead with the election anyways because they would win. The deadline for nominations was at noon on 19 March, and the Election Commission downplayed the coronavirus outbreak to ensure the election would proceed. However, only a few hours later, the president gave instructions to declare an island-wide curfew, and to close the airport to inbound flights. At first, people did not follow the curfew rules, but within a few days it became strictly enforced. Many businesses sprung up to provide services such as the delivery of groceries, food, medicine, gas, and other essential items, while some banks organized mobile ATM services. The island-wide curfew was gradually relaxed, but a few districts, including Colombo, were subject to the full curfew of 52 days, until 11 May.

|

In mid-March, the Election Commission decided to postpone the planned 25 April election indefinitely due to the outbreak, but there was substantial pressure on the commission to hold the elections before 2 June because the dissolved Parliament needed to reconvene by then in accordance with Constitutional requirements which only allowed for a maximum three months closure. In response, the Election Commission wrote to the president to inform him that due to COVID-19, they could not organize an election before 2 June. However, in light of the constitutional constraints, the commission requested that the president seek the opinion of the Supreme Court, which would have the power to invoke force majeure as a way out of the constitutional deadlock. However, President GR responded that it was not necessary. He also disregarded appeals by political parties, trade unions, religious leaders, and civil society to reconvene the Parliament by annulling his gazette that had dissolved it. The adamant behaviour exhibited by the president in his resolve to not parley with the Supreme Court highlighted his preference for exercising strong executive powers at the expense of the legislature and judiciary.

The awkward spike

In the hope of holding elections, the curfew was slated to be lifted on 19 April. The health minister declared that, “by April 19, all possible COVID-19 patients in Sri Lanka will disappear and the people who had it without any symptoms or with mild symptoms will be completely recovered” (Gunatilleke, 2020). Lankadeepa, the weekly newspaper with the largest circulation published a headline reading “The Corona Danger is Over” in its 18 April edition (Fernando, 2020). The same weekend prior to 19 April, a private television channel considered to be pro-president aired a graph that showed a downward trend in the numbers of infections. However, the graph was misleading, as the unit of time of the first three bars was weekly, while the last few bars were measured in daily units. When the public criticized this on social media, the channel’s management admitted that there was a small mistake. The attempt to downplay the outbreak and gear up for a hurried election ultimately failed as on 20 April, a new all-time high of 33 infections in a single day was recorded.

|

Between the time of the first case of COVID-19 on 10 March until 17 April, the total number of positive cases (271) and the number of deaths (5) were still relatively low. From 20 April, however, there was a steep spike in infections due the so-called “Navy cluster.” As mentioned previously, it was the military that was tasked with taking the lead in tracing, tracking and apprehending infected individuals who were hiding their condition to avoid being quarantined. As a result, a number of Navy personnel at camp Welisara became infected. Given the dormitory-style accommodations, the virus spread quickly. By 12 May, the total number of infections and deaths reached 889 and 9, respectively. In terms of the phases of the outbreak, the numbers meant that in Phase 1, it took 38 days to detect 271 positive cases, while in Phase 2, 618 cases were recorded within 25 days. Among these new cases there were 454 Navy personnel. As of 23 March, forty-five quarantine centers were built around the country by the Sri Lankan Army. Since then, 3,500 people have been under quarantine across all the quarantine centers, including 31 foreigners from 14 different countries.

Militarization, rule of law and freedom of expression

Riots broke out in prisons due to overcrowding. These prisons were built to house 10,000 prisoners, but were overcrowded with some 26,000 inmates, making this a high-risk group for COVID-19. The risk was exacerbated by the inability to social distance or practice proper hygiene. In the end, before any coronavirus deaths in Sri Lanka, two prisoners were shot dead during the prison riots.

At this time, Sri Lankans vented their frustrations and criticism on social media about the way in which the government, military, police, and the bureaucracy were handling the COVID-19 situation. The police department warned that those criticizing the government and public officials would be arrested. Several people who criticized the government were reportedly arrested and others were subject to online intimidation and stigmatization. The media reported that the police were seeking to arrest 40 people for spreading false information, and still other reports stated that 17 had been arrested by 17 April (Fernando 2020). Thirty-two trade unions, press freedom organizations, and civil society groups banded together to issue a joint statement which noted that “it appears, under the guise of the suppression of COVID-19 epidemic, the government is suppressing the right of people to express their views and their right to protest. A number of people have been arrested in the recent past for social media posts, and it is seen that top police officers have been threatening people claiming that they will continue to arrest them” (Sri Lanka Brief 2020).

The military played a key role in Sri Lanka’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak. The Army commander was heading the National Operations Centre on COVID-19 and the military was tasked with carrying out search operations for contact tracing and arrests. The quarantine centers were run by the military, often using their camps, infrastructure, and personnel. Moreover, the ministers of health and agriculture were replaced by two military officers on the very first day the country began to reopen after the 52-day curfew. The military was also disproportionately represented on the Presidential Task Force in charge of economic revival and poverty eradication. The judicial system was essentially shutdown during the curfew period creating opportunities to overturn convictions and release cronies. For example, on 26 March, a military member who had been convicted of the murder of eight people, including four children, by slitting their throats and was serving a death sentence, was released by presidential pardon (Asia Times 2020). The domestic media reported this news as if it were the release of a war hero. Additionally, a former diplomat to Russia and a cousin of the president who had been in custody for his alleged involvement in a corruption scandal surrounding the procurement and renovation of aircraft for the Sri Lankan Air Force in 2006, was granted bail on 4 April, while the country was still under curfew (Asia Tribune 2020).

Conclusion

After 52 days of lockdown, the country was finally ‘re-opened’ on 11 May, although between 11 PM to 5 AM the curfew remained in force. On the same day, a retired senior Army officer was appointed as the secretary to the Ministry of Health. This was the first time that military personnel had been entrusted with this post, which had until this point been held by members of the Sri Lankan Administrative Service, who have to undergo years of training and service as well as pass an exam. Two days later, the former minister of health, an actual medical doctor, and ardent critic of the president and staunch member of his opposition, was arrested. During the first week after reopening the country, President GR brought together the senior bureaucrats, including secretaries of ministries and heads of departments to appraise the situation and plan ahead. The president did not mince words when he said to the country’s most senior bureaucrats: “You know what my policies are. You will either need to act according to that or say you can’t and leave. That is what I have to say.” He also expressed his belief that “[he is] doing things the right way and if the right policies cannot be implemented there is no point in having public sector officials” (News Wire, 2020).

Thus, it is important to understand that COVID-19 hit Sri Lanka at a politically significant time when a new president was just settling into his role and preparing to further consolidate executive power. The curfew provided an opportunity for a president who came from a military background and favored the military over existing administrative structures to establish an authoritarian style of governance. At a time when the Parliament had been dissolved and the court system was not fully functioning, the president was able to use and expand executive powers to marginalize legislative and judicial checks-and-balances to further his agenda. While the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak in Sri Lanka may seem relatively limited compared to other nations, it has been exploited politically to consolidate authoritarian governance. Fortunately, the public health consequences were limited owing to a free healthcare system and an efficient public health network. However, the health of democracy, the rule of law, and constitutional freedoms of citizens remain at risk from an equally dangerous virus as COVID-19, one that has been contracted by the body politic of Sri Lanka during the 52 day curfew.

Blog addendum-The author returned to Sri Lanka and described his initial quarantine experience as follows:

Being Repatriated for Quarantine – A Covid Journal

3rd June, 2020, Punani, Eastern Province

|

As a kid, I experienced travel sickness, especially while on winding roads and climbing hills. This made me less motivated to travel as I hated the awful feeling of throwing up and the resultant nausea. But when I was barely 18 years, I had an opportunity to travel to Singapore (one night on transit) and The Philippines for a month. This breakthrough made me a frequent traveller to many places in the six continents of the world throughout the last 34 years. My travels have been less so to the glamourous London, Paris and New York circuit and more to the remotest villages in Laos, Kenya and Senegal. I have stayed in places ranging from boutique hotels to basic guest houses and enjoyed them all.

But all these odd travels had one certainty – there’s either an address of a place to stay or a name and telephone number of a host. That little piece of information could put the traveller in me at peace while what’s on store for work or vacation can be an adventure.

For the first time in my travels, I had a very strange experience in June 2020: I travelled while not having the faintest idea of where I would stay the first night and for fourteen days thereafter. I had no clue if it would be in the North, South, West or East of Sri Lanka. It’s not a country strange to me; for God’s sake, it’s my so-called Motherland! Upon arrival, the returning passengers – like me – were sent straight from the airport, to serve a term of quarantine for fourteen days. There is a choice between a hotel (12,500-15,000 Rs per person per day, about US$65-80) or a government quarantine centre run by the military. The latter is free of charge. Either of these destinations are not known to the returnees in advance. They only get to know the hotels available (often one or two options) upon completion of immigration and other safety procedures. Or, if one choses the government facility as I did, the location is only known when the bus starts its journey.

After a stay of three long months out of the country due to Covid 19 travel restrictions, I boarded the so-called ‘special repatriation flight’, UL 303 to Colombo. The flight was packed with 291 passengers. The in-flight service was limited only to a hurried distribution of a basic meal packs without any kind of beverages, not even a fruit juice. Usually attractive cabin staff looked like ghosts in their HazMat overalls with large goggles and face masks. The entertainment system was not in operation due to safety reasons of having equipment, like earphones, that could transmit the virus. Passengers looked preoccupied in deep thoughts. The flight was unusually quiet except an occasional crying of the only child on board. The little child, less than one year I guess, was with her mother. The child’s father is doing his doctoral studies in Singapore. The child must be missing her father. There was a mix of passengers. The majority belonged to the category of those who got stuck for 2-3 months when they were on a short visit to Singapore. Some have been on transit. There was also a group of students following short study programs in Singapore.

The procedure at the Katunayake airport was well organized, systematic and courteous, given the circumstances within which staff work. First our temperature was tested soon after leaving the plane. Those with high temperatures were segregated and taken to a different location. Others were allowed to enter the airport from a different entrance which is usually used to load luggage onto the carousal. We all stood in line, going forward one by one to dump our masks in a bin and then walked to a corner where they spray water and soap to thoroughly wash our hands. By this time, our hand luggage was taken for disinfection with a spray gun. They use a similar gun to disinfect us too. After this, we are given a new face mask and a pair of gloves. We collected our hand luggage and proceeded to a special immigration counter. Then we proceeded to another to provide health details. The main bottleneck was the long wait for the collection of bags as they only allowed batches of about ten people at a time to approach the carousal. My wait was about 1.5 hours. Upon collection of bags, we reported to a special desk run by the military to register for the quarantine term. This is where the people who came on the same flight and went through the same procedure as equals took two routes. Those who opted for hotel accommodations are given a token of luminous pink and they are quickly ushered to their coaches. This is a small minority. Luminous green token holders, the vast majority, are expected to handover their luggage to be loaded onto a large army truck. Before we board the bus for the quarantine centre, we are given a PCR test. It takes little time but is very painful because the swab is poked through the nostril really deep inside and rotated. The pain and a discomfort remains for a few hours. The results of the test are not given immediately. Rather, they are conveyed 2-3 days later to the quarantine centre or hotel.

I was waiting in the bus for about two hours, not knowing where the bus would finally go. I asked other passengers but they were also in the dark, expressing this by moving their face-masked faces back and forth. Finally, when the driver came. I made a beeline to him to ask where he was taking us. He said ‘Punani’. I asked where that is and he said Batticaloa-side, in the East, about a six-hour journey, telling me to pee now as the bus would not stop on the way. He was a kind man, I must say. Five busses of returnees with green tokens started their journey by 8.20 p.m, escorted by a Military Patrol jeep with a siren and lights and an ambulance at the end. The road was not that busy. The siren of the escort jeep allowed the bus to ‘fly’ while keeping perfect pace with the fast 6/8th-beat non-stop songs played on a radio channel called Sha-Lanka. The music was unbearably noisy and the beats were further thundering hearts already pounding in anxiety. The Sha-lanka songs, in so-called “disti-didin” style, mixed with the annoying sharp noise of the siren and the jeep’s blinking bright red, white and blue lights created an action film-like feeling for the six long hours until the motorcade reached its destination: Punani. This was the controversial Batticaloa Campus of the so-called Sharia University funded by Saudi Arabia that became infamous after the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings in 2019 by Islamic extremists. The government acquired the Campus to set up this quarantine centre.

An efficient group of military personnel received us around 2.30 am in the main Quarantine Centre in Punani. They were well prepared, had our details and were courteous and friendly. But given the large number involved (210) it took another couple of hours for the procedures, orientation and settling us down. The long halls of dormitories with two rows of beds, separated by about 1.5 meters, were arranged. I slept until I was woken up by a hard knock on our door to announce that breakfast was ready. Very thoughtfully, the kitchen of the quarantine centre arranged a pack of rice, onion-sambal and chicken as we had no proper meal on arrival the previous night. I ate every grain of rice and left only the bare bones of the small piece of chicken-curry on the plate sporting the gold-plated logo of the Sri Lankan Army.

References

Asia Times (2020). ‘Rajapaksa pardons sergeant who slit Tamil throats’, 27 March. Hong Kong. (Accessed 18 May 2020)

Asian Tribune (2020). ‘UdayangaWeeratunga Granted Bail’, 4 April. Bangkok. (Accessed 18 May 2020)

Center for Policy Alternatives (2020). Structures to Deal with COVID-19 in Sri Lanka: A Brief Comment on the Presidential Task Force, Guide II, 8 April. Colombo. (Accessed 9May 2020)

Fernando, Ruki (2020). ‘Corona and curtailed Human Rights’, 4 May. Lanka News Web, Colombo. (Accessed 12 May 2020)

Gunatilleke, Nadira (2020). ‘COVID-19 Hang on until April 19- Pavithra’, 12 April. Sunday Observer, Colombo. (Accessed 13 May 2020)

News Wire (2020). ‘President tells state officials to follow his policies or leave’, 15 May. Colombo. (Accessed 18 May 2020)

Sri Lanka Brief (2020). ‘Covid-19 Pandemic and Freedom of Expression Rights’, 16 April. Geneva. (Accessed 28 April 2020)