Abstract

The arrest and detention of Carlos Ghosn attracted global attention to Japan’s treatment of criminal suspects, often described as “hostage justice.”1 Police and prosecutors easily obtain lengthy detentions of criminal suspects prior to filing formal charges during which time attorneys are prohibited from attending interrogations of their clients. Most suspects confess during these interrogations.

Although these conditions remain largely in place, the situation is not static. In fact, over the past decade or so, the number of suspects released from detention who have not confessed has significantly increased. This result has been achieved even though basic provisions of criminal procedure laws have not changed. Instead, earlier access to defense counsel and more proactive work by counsel in challenging prosecutors’ detention requests have made the difference. Today attorneys file more appeals to detention requests and courts grant those requests more frequently, meaning that more suspects are released from custody before trial. In some cases, prosecutors drop charges altogether.

The attorneys’ campaign is having a meaningful effect on the lives of many individuals caught up in Japan’s criminal justice system. Attorneys say that suspects are often detained on relatively trivial charges and detention serves no real purpose.2 In such cases, the most feared penalty is not issued by a court, but by the suspects’ employers. Lengthy detentions can lead to loss of jobs, causing serious damage to the lives of suspects and their families.3

The attorneys who lead this campaign say their goal is “ishiki kaikaku,” a revolution in the consciousness of Japan’s judges. This article describes the evolution in access to legal counsel during the pretrial interrogation stage and results achieved so far by the attorneys’ efforts to fight the heavy use of pretrial detention and the prohibition on attorney presence in police interrogation rooms.

The Right to Counsel in Japan

The 1947 Constitution introduced the adversary system of justice to Japan. Defense counsel formally achieved equal status with prosecutors for the first time. Since then, the powers of the police and prosecutors on one hand, and the role of defense counsel, on the other, have been under dispute.

Constitution Article 37 unambiguously requires the state to provide legal counsel to criminal defendants unable to hire their own.4 The state fulfills this duty through a Court Appointed Attorney system (kokusen bengo seido), in which attorneys designated in specific cases are paid from public funds. The compensation schedule was fixed by the courts until 2006 when the Japan Legal Services Center (see below) took over representation in these cases. As shown in Figure 1, nearly all criminal defendants, including indigent defendants, have long been represented by legal counsel after indictment due to this constitutional requirement.

The situation has been completely different for suspects held in detention but not formally charged. Constitution Article 34 provides a right to counsel after arrest and prior to indictment, but does not compel the state to pay attorney fees during this period. As a result, for many years most suspects were without legal counsel during the critical pre-indictment phase when police and prosecutors detain and interrogate them. Most suspects confess during these interrogations, effectively sealing their fate when their cases come to trial.

The first step in building a system that would adequately protect the rights of criminal suspects was to provide access to legal counsel at an early stage after arrest and prior to indictment. As described below, attorneys began to seriously address this problem in the 1990s.

The “Duty Attorney” System

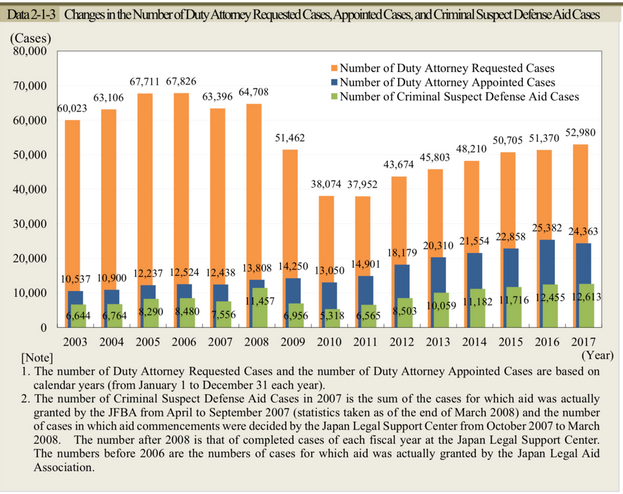

Prior to 1990, suspects unable to hire their own attorneys rarely had legal representation during the pretrial stage. There was a breakthrough that year when the Oita and Fukuoka prefectural bar associations began to offer a pro bono service to persons under arrest. They called this the “Duty Attorney” (DA, tōban bengoshi) system. Under this scheme, bar associations dispatch attorneys after receiving requests from arrested suspects, family members, or others acting on their behalf, including custodial officers.6 The first interview is free. If suspects choose to retain the DA lawyer, then they are responsible to pay attorney fees. In recent years, the number of suspects who request DA attorneys has steadily increased. These suspects choose to retain DA attorneys in approximately half of the cases. Figure 2 shows the trend in recent years. Moreover, suspects are requesting them at an earlier stage. In 2007, only 20% of requests to meet Duty Attorneys were made prior to indictment. This number gradually increased over the following decade. By 2017, it had reached 78%.

Figure 2 7

The example set by the two bar associations was quickly followed by others. By 1992, all local bar associations had begun similar operations.8 Some created special dispatching schemes for specific cases such as murder and serious felony cases that did not require requests from the suspect. Without government support, however, funding was always an issue. For the system to survive and grow, a stable source of funding would have to be found.

The Japan Legal Aid Association was founded by the Japan Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA) in 1952 to provide financial support for legal services to indigent clients. In 1990, the Association began to provide financial aid for defense expenses for suspects unable to pay on their own.9 The source of these funds has been membership fees and surcharges on members of the JFBA and local bar associations. Funding has always been a difficult issue and in an attempt to cover chronic budget shortages, the JFBA established an emergency fund to provide additional support in 1995.10 Eventually, the Japan Legal Aid Association was dissolved, but the bar associations have continued to provide funding. In June 2009, the JFBA launched a new fund for this purpose called the “Fund for Juvenile and Criminal Defense.”11 All of these funds are ultimately paid by member attorneys through bar membership fees and monthly surcharges.12

The Duty Attorney system funded by the bar associations was the sole program devoted to providing legal counsel to indigent criminal suspects until government-funded resources were made available in accordance with proposals in the historic report of the Judicial System Reform Council issued in June, 2001.13

The Government-funded Japan Legal Services Center “Hōterasu”

Responding to the Council’s proposals, the Diet adopted the Comprehensive Legal Support Law in June, 2004. This law created the Japan Legal Services Center (JLSC), an entirely new government-funded legal services network for persons of limited means, including criminal defendants. Commonly known as “Hō terasu,” the JLSC commenced operations in October 2006. Today, the JLSC offers services at more than 100 locations nationwide. The annual budget in 2019 is more than 30 billion yen (approx. US $ 300 million) and it employs approximately 200 attorneys.14

The JLSC offers a wide range of services in civil and criminal matters. It took over operation of the Court Appointed Attorney system (kokusen bengo seido) for post-indictment assignments in 2006 and today also provides legal representation in many pre-indictment cases.

One of the major innovations that arose from the call for judicial reform was the creation of a new system of lay judge trials (saiban’in saiban) for serious criminal cases.15 When this system was launched in 2009 the JLSC began to provide legal assistance for criminal suspects in those cases prior to indictment. JLSC representation of suspects was also expanded in 2009 to include all cases where the assistance of defense counsel at trial is mandatory.16 The scope was further expanded as of June 2018 to cover all cases where a detention warrant has been issued to a suspect.17

Continued Importance of the Duty Attorney System

The JLSC does not cover all cases. This is especially true immediately after arrest. JLSC attorneys are appointed after detention and suspects can be held in police custody for up to 72 hours before meeting JLSC attorneys.

Despite the work of the JLSC, the Duty Attorney system continues to be extremely important and its popularity is growing. As shown in Figure 2, the number of cases in which suspects request meetings with DA attorneys has steadily risen since 2011, reaching more than 50,000 in 2017. This covers approximately half of all detentions. Figure 2 also shows that about half of these suspects choose to retain DA attorneys. (In other cases, suspects may shift from DA attorneys to government-funded representation by JLSC attorneys.)

Because the DA scheme is operated by bar associations rather than the government, funding continues to be an ongoing challenge. In recent years, the percentage of Duty Attorney cases supported by bar association funding has continuously increased, going from less than 14% in 2009 to more than 35% in 2017.

Attorneys Fight to Gain Access to the Interrogation Room

Creation of the Duty Attorney system was a vital step in the campaign to improve access to legal counsel, but problems remained. For example, when attorneys arrived at police stations their requests to meet with clients were sometimes denied. The legal foundation for such denials is found in Article 39 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, which authorizes investigators and prosecutors to restrict the right to confer with counsel “when it is necessary for investigation.”18 This practice is called “designated meetings with defense counsel” (sekken shitei seido).19

Attorneys filed suits challenging these denials and the constitutionality of Code of Criminal Procedure Article 39, arguing that the unbounded discretion exercised by police to deny attorney visits violated the constitutional protection for the right to counsel. The Court noted that both the state’s power to investigate and the right of a suspect to consult with legal counsel are protected by the Constitution. In a ruling issued on March 24, 1999, the Supreme Court rejected the constitutional challenge. In key language, the Court declared that

In order to exercise investigative power, there may be instances where it is necessary to hold the suspect in custody and interrogate the suspect. The Constitution does not deny such interrogations, and therefore, a reasonable balance must be struck between the exercise of the right to consult and communicate with the defense counsel and the exercise of investigative power. It should be acknowledged that Article 34 of the Constitution does not deny the possibility of enacting a provision which strikes such a balance by law, provided that the goal of the Constitution to guarantee opportunities for suspects in custody to be assisted by the defense counsel is not harmed in a substantial way.20

Thus, the Court ruled Article 39 and the designated meeting system constitutional. Despite this loss, the attorneys remained undaunted.

Japan’s courts are divided into separate civil and criminal divisions and judges tend to specialize and spend most of their careers in either civil or criminal courts. During the period from 1985 through 2007, attorneys filed nearly fifty suits in civil courts around the country seeking compensation for financial injury suffered because they were denied the opportunity to communicate and provide effective support for clients. By filing suits in civil courts, attorneys sought to escape rulings in criminal courts, where they saw little hope of success. In the words of one of the leaders of this movement, “Criminal court judges issue rulings based on established practice. Civil court judges don’t know the established practice in criminal cases, so they have to rule based on the law.”21 The attorneys believe the law is on their side.

Although the designated meeting system continued with the approval of the Supreme Court, civil courts nonetheless awarded compensation to attorneys in many of these cases.22 When government attorneys appealed these awards to the Supreme Court, they were disappointed to find the Court confirming the civil court judgments and stressing the importance of early access to legal counsel.23

The pressure of repeated judgments in favor of the attorneys inevitably led to relaxation in the use of the “designated meeting” system to deny attorney access to suspects in detention, resulting in more frequent and lengthier consultations with legal counsel at an early stage of their confinement.

This reform was achieved not by legislative action or by courts ruling directly on issues of criminal procedure, but instead by the initiative and creativity of attorneys themselves in their long-term campaign to provide better legal assistance to persons accused of crime. Ironically, they achieved progress in criminal procedure by avoiding the criminal courts.

Impact of the Campaign

As explained above, access to legal counsel by persons under arrest has continuously expanded over the past two decades. In this section we will introduce some key indicators that suggest the campaign is having a significant impact.

The central complaint of critics who label Japan’s system “hostage justice” is that detainees are faced with a choice between confession and continued detention. In other words, they say that confession is a condition of pre-trial release and nearly all suspects confess as a result.24

In Japan’s criminal justice system, prosecutors have the sole authority to request that suspects be detained and courts have the sole authority to approve or reject these requests. In the past, courts approved nearly all requests and rejected nearly all challenges by defense counsel. According to JFBA data, during the period from 1990 through 2007 fewer than one percent of challenges to prosecutors’ detention requests were granted.25

Recent data shows a significant decline in detentions. This decline is primarily the result of the proactive stance of defense attorneys who challenge court detention orders more frequently and of judges who are more willing to recognize those challenges and release suspects from detention.

The first important metric shows the courts’ responses to prosecutors’ detention requests. In 2010, prosecutors sought detention orders for 114,567 suspects. Courts approved 98.9% of the requests, ordering release of only 1,237 persons. Since then, judicial resistance to detention requests has steadily increased. In 2018, prosecutors filed detention requests for 95,079 suspects. Courts approved 95.1%, ordering release of the remaining 4,888 suspects, nearly four times the number released ten years earlier.26

In cases where courts grant prosecutors’ requests, defense attorneys can file oppositions. Whereas initial detention decisions are typically decided by a single judge, these defense challenges must be decided by a three-judge panel, thus opening the door to more thorough scrutiny of prosecutors’ requests. In years past, attorneys rarely made such challenges, but over the past decade the number has dramatically increased. Between 2008 and 2018, the number of defense challenges to detention more than doubled, rising from 4,706 to 13,263. The rate of approval has remained roughly the same at approximately 20%, so the number of individuals released over the ten-year period rose from 1,005 in 2008 to 2,541 in 2018.27

The change in the attitudes of the attorneys and courts appears to have affected prosecutors as well. They joined the trend to reduce the heavy use of pre-trial detention by more frequently releasing suspects without prosecution. In 2008, prosecutors declined to file charges in 26.5% of cases. By 2018, the percentage had risen to 37.2%. More than 33,000 suspects were released by prosecutors’ decisions to drop their cases that year.28 If prosecutors had acted at the 2008 rate, more than 3,000 additional persons would have gone to trial.

Whether by action of the prosecutors or the judges, the bottom line is that many more detainees are released prior to indictment. Many observers suggest that the primary reason for this result is attorney activism, in particular, suspects’ improved access to defense counsel prior to indictment.29

Expectations for the Future

Attorneys and bar associations are continuing their campaigns to expand the right to counsel and to gain freedom for their clients. Progress has been understandably slow, but steady. If the Diet passed groundbreaking legislation or the Supreme Court issued a landmark judgment, change could be very rapid. But this has not happened. Instead, change has been bottom-up, the result of advocacy in individual cases and the willingness of lower court judges to impose tighter requirements to keep people in jail before trial. The attorneys’ campaign is targeted at these judges and the objective is nothing less than a “revolution in consciousness” (ishiki kaikaku) among them.30 As noted above, the Supreme Court has approved civil awards for compensation in cases where attorneys were denied visits with detained clients. However, the Court has not produced rulings that directly reform criminal procedure.31

Poor legal protections for criminal suspects in Japan are largely the result of Supreme Court decisions. Anyone who simply reads Japan’s Constitution gets the strong impression that Japan provides robust protections for the rights of persons under arrest. Constitution Articles 31 through 40 declare many important protections, including rights to the due process of law, to a speedy and public trial, to remain silent, and others. However, Japan’s Supreme Court has refused to take an expansive view of these provisions in a manner that would protect individuals held by the police.

In this article, we have focused on the right to counsel protected by Constitution Articles 34 and 37. As we have seen, despite constitutional language that guarantees a right to counsel, the Supreme Court has nonetheless approved prosecutors’ use of the “designated meeting system” to limit access to counsel. Moreover, the Court has tolerated the practice of barring defense counsel from interrogation rooms. Another Supreme Court precedent that sharply impacts persons under arrest concerns the right to remain silent, protected by Constitution Article 38. Instead of ruling that when a suspect invokes this right police and prosecutors’ interrogations must cease, instead the Court ruled that interrogations may continue unimpeded.32 As interrogations continue, often for many hours per day, suspects are denied the presence of legal counsel at their side.

Unfortunately, at present there is little reason to expect a change in the attitude of the Supreme Court toward these issues.33 But the attorneys’ bottom-up strategy is achieving results and they have vowed to continue their campaign.

Many local bar associations have started programs to support members who challenge pre-trial detentions. For example, in Kyushu and Okinawa (courts under the jurisdiction of the Fukuoka High Court), during the period from June through August 2019, attorneys challenged detention requests in 250 cases. Suspects were released from police custody in 98 of the cases.34 Similar campaigns have been launched in Kanagawa, Aichi, and elsewhere. In Aichi’s case, the prefectural bar association actually provides small financial grants to attorneys who file these challenges. (The amount of the stipend is 10,000 yen per case. The bar association’s goal was to support 800 cases within a three-month period.)35

As the bottom-up strategy continues in trial courts around Japan, at the national level the JFBA has launched a new campaign addressed to another fundamental aspect of the right to counsel: the presence of defense counsel during interrogations. In demanding this reform, JFBA leaders seek to emulate their success in the related issue of video recording interrogations. The JFBA achieved partial success when video recording was required regarding interrogations related to lay judge trials, which are required in cases of homicide, robbery resulting in serious injury or death, arson, and other serious crimes.

Persistent lobbying by the JFBA was the primary force behind this reform. The JFBA’s work, supported by the news media and public opinion, led to a report recommending video recording in a limited range of cases by the Legislative Council (hōseishingikai), an important advisory body to the Ministry of Justice, in 2014. The Ministry drafted legislation based on the Council’s report which was submitted to the Diet and passed on June 3, 2016.36 Mandatory recording commenced on June 1st, 2019.37

Although broad public interest in reform was sparked by disclosure of a prosecutor’s evidence tampering in the heavily reported Muraki case,38 there is no doubt that without the JFBA’s longstanding campaign, the Legislative Council would not have adopted the idea.

The right to presence of counsel during interrogations is even more fundamental than video recording. As described above, the attorneys’ efforts to gain constitutional recognition of this right were rejected by the Supreme Court in 1999. In its campaign launched in 2019, the JFBA focuses on Diet legislation rather than the courts.39 Advocates hope that the process that led to the video recording requirement will serve as a model for future legislation to require attorneys to be present during interrogations.

Final Comment

Japan’s Supreme Court has generally refused to interpret constitutional provisions in a manner beneficial to persons accused of crime. Lengthy detentions with minimal access to counsel have been the result. On the other hand, the attorneys’ zealous advocacy in the day-to-day work of representing individual suspects before lower courts has achieved meaningful change in recent years. If the attorneys succeed in their new campaign to require the presence of counsel in the interrogation room, this will be an even greater victory in the cause of justice for persons accused of crime.

Notes

See “Call to Eliminate Japan’s ‘Hostage Justice’ System by Japanese Legal Professionals,” an English translation.

The relevant language in Article 37 reads “…At all times the accused shall have the assistance of competent counsel who shall, if the accused is unable to secure the same by his own efforts, be assigned to his use by the State.”

2017 White Paper on Attorneys (bengoshi hakusho), page 41. Readers will notice that the chart shows a decline in the number of arrests over the past 15-year period. Study of the reasons for this decline is beyond the scope of this paper. Makoto Ibusuki recommends the following two articles for fruitful discussion of this issue: Koichi Hamada, “Why is the Number of Crimes Decreasing?”「なぜ犯罪は減少しているのか, 」浜井 浩一, 犯罪社会学 研究 第38号 2013年; and and Taisuke Kanayama, “The Declining Number of Crimes in Recent Years and the Metamorphosis in Crime”「近年の刑法犯の減少と犯罪の転移,」金山泰介, 早稲田大学社会安全政策研究所紀要 (8), 17-37, 2015

Japanese attorneys (bengoshi) are required to register in both a local bar association and the national Japan Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA). Mandatory bar associations are established for each prefecture.

The Japan Legal Aid Association (法律扶助協会) was founded by the JFBA in 1952 to provide funding for legal services. It was disbanded in March 2007. This program was called the Criminal Suspect Defense Aid (CSDA) (被疑者弁護援助制).

The JFBA is still collecting the fee from the members every year. The monthly fee was 1,900 yen until it was reduced in May 2020 to 1,600 yen per month.

Mark Levin and Adam Mackie have published an exhaustive listing of English language material that discuss the Council and subsequent reforms. See Levin and Mackie, “Truth or Consequences of the Justice System Reform Council: An English Language Bibliography from Japan’s Millennial Legal Reforms,” Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal, Vol. 14, No. 3 (2013). For a brief overview, see Daniel H. Foote, “Introduction and Overview,” in Foote (ed) Law in Japan – A Turning Point (University of Washington Press, 2007).

Regarding the launch of lay judge trials, see Kaori Kano & Stacey Leanne Steele, Japan’s Lay Judge System (Saiban-in Seido) and Legislative Developments: Annotated Translation of the Act Amending the Act on Criminal Trials with Participation of Saiban-in, and Makoto Ibusuki, “Quo Vadis?”⁑: First Year Inspection to Japanese Mixed Jury Trial (2011)

Criminal Procedure Code Article 289: “When a case is punishable by the death penalty, life imprisonment, life imprisonment without work, or imprisonment or imprisonment without work whose maximum term is more than three years, the trial may not be convened without the attendance of defense counsel.”

Code of Criminal Procedure Article 39 (3): “A public prosecutor, public prosecutor’s assistant officer or judicial police official (“judicial police official” means both a judicial police officer and a judicial constable; the same shall apply hereinafter) may, when it is necessary for investigation, designate the date, place and time of the interview or sending or receiving of documents or articles prescribed in paragraph (1) only prior to the institution of prosecution; provided, however, that such designation shall not unduly restrict the rights of the suspect to prepare for defense.”

Daniel Foote discusses the general designation system and notes that in 1988 the Ministry of Justice revised internal guidelines in order to relax the use of the designation system in “Policymaking by the Japanese Judiciary in the Criminal Justice Field,” Hōshakaigaku, vol. 72, p.6, at 15-16. (2010)

Judgment of the Supreme Court Grand Bench, March 24, 1999. Minshu Vol. 53, No. 3, page 514. (最高裁大法廷平成11年3月24日民集53巻3号514頁)

E.g., Supreme Court (3rd P.B.), Judgment of June 13, 2000, 54 Minshū 1635, and Supreme Court (3rd P.B.), Judgment of April 19, 2005, 59 Minshū 563. Daniel Foote discusses these cases in “Policymaking by the Japanese Judiciary in the Criminal Justice Field,” Hoshakaigaku, vol. 72, p.6, at p. 38.

See “Call to Eliminate Japan’s ‘Hostage Justice’ System by Japanese Legal Professionals,” an English translation.

Professor Hiroyuki Kuzuno of Hitotsubashi University was one of the first to make this connection. Hiroyuki Kuzuno, “Keiji Shihō Kaikaku to Keiji Bengo (Judicial System Reform and Criminal Defense)” (2016), p 333-335.

Makoto Ibusuki is skeptical regarding the effect of civil judgments on police behavior.

He addressed this issue in an expert opinion submitted to the court in the infamous Shibushi case. The case was reported by The New York Times. See Norimitsu Onishi, “Pressed by Police, Even Innocent Confess in Japan,” (May 11, 2007). See also the Japan Federation of Bar Associations comment.

Many members of Japan’s legal community are aware of principles laid down by the U.S. Supreme Court in cases such as Miranda, Escobedo, and Gideon, but these U.S. developments seem to have had no impact on the Supreme Court.

For background on the 2016 reforms, see S. Umeda, “Japan: 2016 Criminal Justice System Reform,” The Law Library of Congress.

“Japanese police and prosecutors now required to record some interrogation”, Japan Times, June 1st, 2019.

The U.S. Supreme Court has not ruled that criminal suspects hold a right to have interrogations video recorded. However, at least since the Miranda decision in 1966, American suspects have had the right to presence of counsel during interrogations, which is still denied in Japan.

Video recording employed by U.S. states is usually based on a law passed by each state legislature. There are only two states where court decisions mandate recording of suspect interrogations. See, Alaska: Stephan v. State, 711 P. 2d 1156 (1985), Minnesota: State v. Scales, 518 N. W. 2d 587 (1994). On the other hand, some states have court rules requiring the video recording of interrogation (New Jersey, Indiana and Arkansas).

For the Muraki case, see articles below from Japan Times, Nippon.com and The Asia-Pacific Jounal: Japan Focus.

Japan Federation of Bar Associations, “Declaration Demanding Establishment of the Right to Receive the Assistance of Counsel – Attendance During Interrogations Will Change Criminal Justice”, October 4, 2019. (弁護人の援助を受ける権利の確立を求める宣言 — 取 調べへの立会いが刑事司法を変える)

2019年(令和元年)10月4日 日本弁護士連合会