Abstract

The Korean War would generate a wide range of cinematic responses. The fledgling film industry of South Korea produced films that, in sync with an ideology of stark anti-communism, tended to emphasise the immediate physical brutality of the communist enemy. The reaction of American film makers was at first to reproduce the narrative shape and tropes of the very successful films from World War II, usually situated in Europe or the Pacific Islands. Gradually, however, Cold War paranoia about enemies within and about the new insidious threat of ‘brain washing’ took hold in Hollywood, as it swept through other social and political discourses and institutions. This paranoia, a sense of diffuse panic was not limited to the war film genre but leaked out creatively into a new genre of science-fiction features.

Keywords

Korean War film, anti-communism, Cold War paranoia, science-fiction film

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Introduction

This year, 25 June 2020, will mark the seventieth anniversary of the beginning of the Korean War. On Sunday, 25 June 1950, a massive army of North Korean soldiers and tanks crashed across the 38th Parallel into South Korea. The commemoration of most twentieth-century wars seems to focus on the end of the fighting: 11 November for the First World War – a date much more significant in the UK than the US; 8 May VE-Day and 15 August VJ-Day for the Second World War. It is of course that last date, 15 August, which is celebrated in both of the Koreas as the day of national liberation, though rather predictably the two nations call it by different terms. The South has the more poetic Gwangbokjeol , ‘the day the light was restored’; the North makes do with the prosaic Jogukhaebang ui nal, ‘the day of fatherland liberation.’

The Korean War did grind to a halt with an armistice signed on 27 July 1953. But that date has not inspired much commemorating. The war ended in a bloody stalemate and there has never been a peace treaty between the main combatants. The two Koreas, the US and North Korea, all are technically still at war. So it is the beginning date of 25 June – the Korean short hand is yug-i-o/6-25 – that remains firmly seared in collective memory.

South Korea had begun to develop its own small-scale film business after the end of the Second World War and the defeat of the Japanese colonizer. The destruction and dislocation caused by the Korean War meant that Korean film-makers would only begin to recover by the latter half of the 1950s. Given what they and their country had been through, it is not surprising that neither film producers nor their audiences rank war films high on the entertainment agenda. There was one film about the communist guerrillas (Piagol 1955), a bio-pic about a courageous army officer (Strike Back 1956), but in general melodrama and historical costume drama were the genres that would prepare the way for the future ‘golden age’ of 1960s cinema.

By that decade audiences had enough distance from the war to accept fictional versions of it; script writers and directors had themselves learned lessons from foreign, usually American films about how to make a film about war that had a gripping plot, believable characters and an acceptable ending. For both Koreas the war had ended in a bloody and futile stalemate. Everybody lost almost everything. The narrative arc of a Hollywood World War II film could take the audience along, confident that, whatever the sufferings of this platoon or that brave soldier, victory over the axis powers made it all worthwhile. Korean filmmakers would have to find solace in other places. In the North, the cult of Kim Il-sung would be elaborated to present the catastrophic war as a victory over American imperialism.

In South Korea, combinations of individual bravery and patriotism with the state ideology of anti-communism could be relied upon to provide some sense to the chaos. While many battlefield action films were made, some of the best Korean visions of the war deal with the effects of the war on the civilian population. There are many varieties of film dealing with the destructive impact of the war on ordinary people. Here Korean filmmakers had to find their own way. The premise of Hollywood war films was that, mercifully, the actual fighting took place far, far away: on French beaches, blasted German towns and cities, tropical islands in the Pacific, jungles in the Philippines. Koreans had no luxury of distance. The war may have been in your own street or village road, blasting through the doorway, devouring your family as you watched. There were no non-combatants, only people more or less lucky — or more or less ruthless.

There are many similarities between films made in South Korea and in the United States concerning the Korean War. For example, a very early battlefield drama by director Lee Kang-cheon 이강천, Strike Back <격퇴> 1956, centred its action on the capture and defence of a crucial hilltop by a squad of ROK troops (making it the cinematic grandfather of a 2011 film like Front Line <고지선>). It anticipates the main features of a Hollywood ‘classic’ such as Pork Chop Hill of 1959. South Korean and American films, however, probably display more contrasts than similarities, different kinds of political and cultural ideology — styles of Cold War panic: this seems particularly the case with films which treat the horrors of the Korean War in the context of, on the one hand, South Korean anti-communism and, on the other, American Cold War paranoia. This essay beging with a consideration of an early example of what I have termed ‘war horror’ (Morris 2013) from the film Lee Kang-cheon made before Beat Back, Piagol <피아골> 1955. Piagol was the first feature film about communist partisans. South Korean films concerning the Korea War would, from this era through the 1970s and beyond, develop a grammar of scenes of extreme physical violence to represent the merciless inhumanity of communism generally and of North Korea in particular.

The focus then shifts to one significant American film set in and partially shot in South Korea. The kind of physical, explicit threat of North Korean infiltrators in the early war film Korea (1952) would soon be displaced to a more insidious form of infiltration. From the early to mid-1950s, during the McCarthy-era, cinema fastens attention on the fear and panic concerning the fate of American POWs. By 1950 the word ‘brain-washing’ had been coined and popularised through the efforts of CIA-affiliated journalist Edward Hunter. A complex journalistic and pseudo-scientific discourse emerged: brainwashing, panic concerning Communist fifth-column infiltration of the body politic and, worse still, the minds of soldiers and civilians – all make up the theme music for 1950s America. This fear of alien infiltration/mind-control migrated with surprising ease into an emerging genre of sci-fi horror: here the ‘classic’ is Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). The summa panicorum of this Cold War moment comes in John Frankenheimer’s 1962 film The Manchurian Candidate.

This essay began as a chiefly visual presentation, one focused on film clips, in order to emphasise the concretely visual language of Cold War panic. In an attempt to follow the zigzag path from Korean bamboo spears to American fears of alien invasion, body and brain snatching, the essay will try to crystallise this visual register in individual scenes from some representative films. Interested readers are invited to consult the VIDEO SUPPLEMENT at the end of the main text for links to numerous films, clips and trailers

Terror on the tip of a bamboo spear

Scene 1: Piagol <피아골> (Lee Kang-cheon 이강천 1955)

A group of partisans operating in the Jiri Mountains returns from a raid on a local village. They have brought back a calf, rice and other booty as well as several villagers taken prisoner. One of them is a village notable accused of informing on the group’s activities. Two poorer villagers are forced to kill him with bamboo spears.

The cinematography, the work of director Lee’s key collaborator Kang Young-hwa, is extraordinarily accomplished. Here, the characters are arranged in the empty courtyard of an old mountain temple. Shot through a night-for-day filter, the setting’s eerie night-time atmosphere is only betrayed by a few unavoidable shadows. When the poor farmers are offered the choice of either killing the local notable with bamboo spears or being themselves shot dead on the spot, Kang’s camera shots a striking close-up: the tips of the spears are lined up right next to the barrel end of a rifle, all brought into relief by the play of light glinting ominously from them. The actual killing is downplayed. The man kneels, cursing the red partisans as the two villagers make perfunctory stabs at his back. What carries the shock of violence is the image of those glinting spear tips.

|

Piagol, 1955 |

This may be the first cinematic representation of what would become a standard topos in anti-communist war films: poor peasants forced to kill innocent, political/respected Koreans in the cruellest possible way with bamboo spears. The perversion of social order is matched with the corruption of the peasant weapon of first and last resort, the bamboo spear 장, into an arm of communist oppression. The director would return to the same material later as his career as anti-communist film-maker was secured by films such as Dae-jwa’s Son <대좌의아들> (a.k.a. Son of the General 1968).

Piagol was released in 1955. Hindsight allows us to see this point in time as the beginning of a Golden Age for film in South Korea. Piagol attempted to appease South Korea anti-communist common sentiments yet still present an historically informed, relatively balanced representation of leftist/communist partisan fighters; the doomed partisans of Piagol have been left stranded in the South after the main phase of the war ended in stalemate and the Armistice of July 1953 confirmed the bloody status quo. Lee Kang-cheon’s film caused a significant public debate, even after censorship had altered certain scenes. The material Lee used to write his scenario had been provided by Kim Cheong-hwan, an officer with the Northern Cheolla Provincial Police. Kim’s name is given prominence in the credits as scriptwriter, even though director Lee did most of the actual writing. It was one way to show appreciation, yet also a fairly wise means of attempting to inoculate the film from unwanted suspicions of left bias. The narrative Lee constructed with the policeman’s help was put together from diaries and letters taken from partisans who had held out in the Jiri Mountains until their capture, surrender or death. From these fragments, fragments from an impeccable anti-red source, one might have thought, Lee fashioned a scenario that could claim to represent partisan experience from the inside. This may have been the beginnings of Piagol’s problems with the censors.

When Piagol was finally released in September of 1955, it went on to become a success, both commercially and artistically. Controversy about the film which appeared in newspapers during the summer had stirred up interest, as had the sight of posters for the film going up at one Seoul theatre then down again as the censors grumbled, only to pop up at another as the waiting continued. Some of the first film awards established in South Korea, the Golden Dragon Film Awards, went to the film: Best Film, Best Director, and Best Actress for No Kyeong-hui 노경희 as Ae-ran. The film introduced two other actors who would be mainstays of the film industry for many years to come: star-in-the-making Kim Jin-kyu 김진규and the famous character actor and villain for all seasons, Lee Ye-chun 이예춘.

The complete film Piagol is available for viewing here.

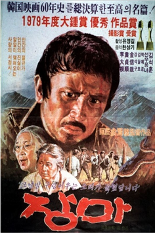

Scene 2: Rainy Days <장마> (Yu Hyeon-mok 유현목 1979)

Slow-witted villager Sun-ch’eol (Lee Dae-geun 이대근) has joined local red auxiliaries who are re-organising village life as the main People’s Army advances deep into the South.. When suspected of aiding a ROK soldier – who, to make matters worse, is his own relative – to escape, he is accused of being a bandong 반동’reactionary’. In anti-communist films, the word usually proves fatal to anyone labelled with it. Sun-ch’eol knows that much. He proves his desperate loyalty by agreeing to execute four elderly, respected village friends. He grabs a proffered bamboo spear and charges at the poor men tied to posts set by the river’s edge; the spear misses, he flings himself past them and lands in a heap on the gravel. But the next time the spear bites home, then into another victim, then one more.

Most of the scene is shot from behind the bound men, but is nonetheless grim, especially the terrified growl of Sun-ch’eol and the death agonies of his victims. Close-ups of Sun-ch’eol’s face and the spear in his hands emphasize the mix of sweat, fear and blood that end his final moments in his native village. The violence is more directly expressed than in Piagol. The scene is in broad daylight and of course colour plays a more direct role. Director Yu uses a zoom, rather than clever framing and lighting, to focus on the spear in Sun-ch’eol’s hands, picking up the red artificial blood on the spear but also on Sun-ch’eol hands and face.

|

Rainy Days, 1979 |

The key topos of war terror was going strong a quarter century after the making of Piagol. A well-loved short story by Yun Heung-gil 윤흥길provided the title and basic elements of plot and character. Yet in this remarkably sad yet lyrical short story, told through the eyes of a young boy, the violence is resolutely off-stage. The young boy narrator experiences war as a plague descending upon his family. One uncle is brought back for burial, the other, Sun-ch’eol, eventually disappears into the mountains with the retreating Northern army.

At one point red partisans have raided the local town, but the result is disastrous. Their bodies are left strewn around. Yet all we know of the brutal event is what the boy hears from his father’s report to the family. Director Yu and scriptwriter Yun Sang-yuk seem to have taken one passing comment by the boy as their cue to provide the film with suspense, action and an inoculation of anti-communist sentiment. This is the whole passage: ‘From time to time, from the dark corner of the sky, lightning darted out and pierced Gunjisan as sharply as the bamboo spear that I once saw being thrust into a man’s chest on the village road beside the dike’ (Yun 1989: 14). This is poetic and understated, but chilling for all that, registering a primal scene that will haunt this once innocent boy through the rest of his days.

Overall, most critics looking for something positive that Yu Hyeon-mok brought to Yun Heung-gil’s story de-emphasise the director’s insistence on the evils of communism and, instead, emphasise his efforts to locate in native Korean beliefs a power to heal the rift between warring peoples (KMBd Jangma).

The key role of Sun-ch’eol is played by Lee Dae-geun. He represented something of a new physical type of actor emerging from the late 1960s. Through the 1970s into the 1980s, his type of stocky, square-jawed, naïve but natural, honest masculinity became a mainstay of action and historical films: his brothers in the creation of the prototypical male protagonist were actors such as Kim Hee-ra 김희라and Baek Il-seob백일섭. It is difficult to imagine any of them within miles of a gym or personal trainer. Clearly, Lee’s decade-long acting profile made him a natural for Sun-ch’eol. It may seem contradictory to match naïve masculinity with the treachery demonstrated by Sun-ch’eol in the above scene. The latter scenes of Yu’s film, however, perform a double exorcism, purging his crimes. His mother — played by the quintessential Korean omoni, Hwang Jeong-sun 황정순– exorcises his dead spirit, returned home in the form of a snake. Yu’s film seems calculated to exorcise him as well as the conflict which engulfed Korea by thus allowing his spirit to reclaim its most important quality: its essential, uncontaminated Koreanness.

Rainy Days complete video available here.

Infiltrators: enemies within

Scene 3: Korea [a.k.a. One Minute to Zero] (Tay Garnett 1952)

US Army officer Steve Janowski (Robert Mitchum) learns that apparently innocent columns of white-clad refugees are being used to infiltrate North Korean soldiers behind the American lines. His soldiers encounter such a column and block the road before it. An old man protests loudly, in one of the few real Korean voices heard in the film. Soon the soldiers discover a baby buggy hiding a machine gun (how likely would it be that frightened farmers would be pushing baby-buggies along Korean roads in the summer of 1950?); then they grab a North Korean soldier dressed as a woman. ‘There’s someone here from Moscow, colonel,’ wise-cracks one of the GIs.

Thus set up, the sequence shifts to the perspective of Janowski’s artillery post, some distance from the roadblock. He has to decide how to stop the column when, despite his men, it starts advancing towards American lines. The American guns start laying down shell fire just in front of the column, gradually marching the murderous explosions closer. We cut to shots of determined-looking men forcing the terrified people forward, concealing weapons and their army uniforms as best they can. Reluctantly but firmly, Janowski finally gives the order to put the shells right on top of the defenceless people.

Korea/One Minute to Zero complete video available here.

|

Spanish poster for Korea, 1952 |

The tragedy of the Korean War is a main theme of the film. And the scene of the shelling of terrified innocent ‘Koreans’ is still shocking today. Shots of individuals or small groups in the crowd are intercut to increase tension. But the latter are framed most often as a white-clothed blur of humanity, enacted by a confusing mix of nationalities – Chinese, Filipino, Mexicans, etc. – the usual extras for films set in East Asia. (This despite sleight-of-hand, which blends moments of actual footage of real refugees with scenes staged in Colorado.) The only suffering the Hollywood style really captures is through close-ups: close-ups of guilt concerning the painful, but supposedly unavoidable order to destroy the civilian column, flickering across the smouldering good looks of big Robert Mitchum; or sorrow reflected in the big blue eyes of impeccably coiffed and dressed Anne Blyth, his girlfriend. She is in Korea working for the UN and witnesses the shelling. Her wisdom lies in learning from it, rather than any lesson about the brutality of American’s invention, how her lover has suffered in the effort to thwart Communist aggression. Any possible lessons concerning the fate of Korean civilians caught up in the conflict – such as the massacre that occurred at a village like Nogunri – lay well in future. They would come to matter greatly to South Korea, much less so to America with its short attention span and many, many wars (for a brief up-date on a huge topic, see Hanley & Mendoza).

Early Hollywood efforts to put the Korean War on screen tried to accomplish a number of patriotic tasks. Here, growing if understated concern over South Korean civilian deaths, due to America’s massive use of firepower from air and ground forces, seems both recognised and immediately cancelled out: the treacherous commies thought little of forcing their own people into the mouths of the cannons, American troops were forced to respond. Before American fears about red infiltration of the minds and souls of soldiers or civilians came external ‘proof’ of communism’s insidious, invasive ruthlessness.

For the most part, the American studios never knew what to do about or what to do with the Korean War. When the war began in June 1950 their focus was still on turning out films about the Second World War. Of the top 50 box office successes that year, eight were films about that war, including the John Wayne guts-and-glory epic, The Sands of Iwo Jima. ‘At this stage, most movie executives viewed Korea as little more than a regrettable irritant that promised to disrupt their working relationships with the military, relationships that were necessary to give authenticity to the spate of World War II movies then in production’ (Casey 2008: 219-20). While low-budget features had appeared early on, it was unusual for Howard Hughes and RKO to develop a major project in this climate. Not released until July 1952, the film was disowned by the US Defense Department, who had initially assisted in the production. They were ‘annoyed by the final scene, in which Mitchum orders the artillery to fire on a line of refugees that also contains north Korean soldiers’ (Casey 2008: 408). As a note, the American Film Institute entry for the film observes, ‘One Minute to Zero marked the first time that any major studio received military cooperation during production, then lost it upon release (AFI One Minute to Zero)’.

Infiltration on the home front was of course a key theme and plot device for a number of anti-communist films emerging in the McCarthy era, such as I Was a Communist for the FBI (1951). ‘Because so many of these films were shot quickly on low budgets with non-stars’, as Tony Shaw has observed, ‘many historians have assumed that they were not intended either to make money or to teach the American public anything of real value about subversion (Shaw 2007: 52).’ Film makers and studios were nervous about how their earlier, more liberal-looking products of the 1940s might reflect in the eagle-eyes of red hunters. So, in part, the anti-communist quickies ‘were meant to rinse Hollywood of its radical image (Ibid.)‘ But as Shaw’s research demonstrates, there was much more to the ‘Hollywood-state’ nexus through the entire old War era.

It would be the experience of the Korea War and the fate of American POWs held captive in North Korea under the control of Chinese gaolers, interrogators and other ‘educators’ that would shift American paranoia away from a focus on physical, actual infiltration — abroad or at home — to a fixation on mind control and that almost mystical process expressed as brain-washing.

Tortured bodies, captive minds

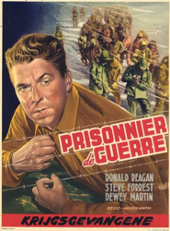

Scene 4: Prisoner of War (Andrew Marton 1954)

A Soviet officer festooned with campaign medals is working as adviser to a Chinese (or Korean?) prisoner of war camp commander, Colonel Kim. ‘Well now, comrades, we are here to help you handle any detail of the prisoners’ daily life – of course you are in charge – we are merely your guests here.’ Colonel Kim states his puzzlement over the fact that the Americans under his thumb still resist and maintain their spirits.

At which point the Soviet guest launches into a brief tribute to ‘one of the great scientists of the world, Ivan Petrovich Pavlov’. Pavlov experimented with cats and dogs, but now ‘we are going beyond Pavlov because we are dealing with a higher organism, man.’ Kim asks: ‘Will this work with Americans, comrade?’ ‘It will work with anybody,’ is the confident Soviet response.

|

French poster for Prisoner of War, 1954 |

The star of this clunky Cold War ‘classic’ was a future American president. ‘When Prisoner of War came along, the 42-year-old Ronald Reagan . . . was in a bit of a career slump. Since 1950, he had bounced from one studio to another and had recently resigned as President of the Screen Actors Guild. Reagan had been turning down most of the lackluster movies offered him during this period. However, when MGM sent him the screenplay for Prisoner of War, he loved it and signed on to the project right away’ (TCM Prisoner of War).

In the film he plays an army intelligence officer who is parachuted into North Korea for the purpose of gathering information about the horrible conditions in the POW camps and the many violations of the Geneva Conventions. He pretends to sympathize with the communist cause and becomes a ‘progressive’, that category of co-operating, perhaps collaborating POW whose antithesis was labelled a ‘reactionary’ by the evil reds. For all the talk early in the film of Pavlov and conditioned reflexes, the Chinese guards proceed to beat and torture their prisoners with little regard for psychological finesse. The climax of their Asiatic cruelty comes in a scene where, in front of a helpless POW, they beat his pet puppy to a pulp. ‘An old Chinese custom,’ comments the Reagan character Webb Sloane (Carruthers 2009: 198).

Prisoner of War was designed to capitalise on the return of the American prisoners of war after their long captivity. It was a very confusing era in which any simple joy in our boys coming home was troubled by rumours of how badly they had suffered. Worse was to come, as it became known that not all had behaved as total heroes: many had, under severe physical (or was it mental, spiritual?) duress, signed statements opposing American imperialist ambitions or made broadcasts denouncing their government; others put their names to claims that the US had engaged in biological warfare. Some had betrayed fellow prisoners to their captors. ‘Out of 4428 POWs returned, the conduct of 565 was seriously questioned’ (Young 1998). And worst of all were the certified traitors, the 21 American soldiers who refused repatriation and ended up instead in China.

Television was first to dramatise the confusing plight of these almost mysterious returnees. NBC’s The Traitor was quickly followed by a rival network’s POW during the autumn of 1954. During August, MGM secured army approval to start a film project. ‘Two days later, when the first transport docked in San Francisco with a consignment of 328 former prisoners, the screenwriter Allen Rivkin was waiting on the dock to conduct interviews’ When the film was released in May of 1954, ‘MGM bragged that it had set a “speed record for the development from original screenplay to actual filming of a motion picture,” four months and two days’ (Carruthers 2009: 196-97).

|

Prisoner of War, 1954 |

Maybe they should have slowed down. ‘Prisoner of War offended just about everybody. The Army distanced itself from an “unhelpful” production it had initially supported with gusto. Movie critics, meanwhile, passed harsh judgment on a feature that handled a sensitive topic so crudely’ (Ibid: 198). In the scene described above, the Soviet officer is played by Austrian actor Oscar Homolka, Hollywood’s favourite rent-a-‘Russian’, while his interlocutor is the Asian-American character actor Leonard Strong. During World War II, Strong had minor roles as Japanese villains, while during the Cold War he would be cast usually as Chinese – he even had a role in the mid-1950s television version of Fu-Manchu. Their stilted dialogue gives a comic-book rendition of the American anti-communist mantra: The Korea War and its aftermath were planned and funded by Moscow, Red Chinese acted under instruction as partners in the conspiracy, whereas North Koreans were bit actors in the drama of the communist threat. This disappearance of the reality of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea as a sovereign state with any claims to legitimacy harmonised only too well with the shared ‘advance North’ (북진) strategy of both Allied and ROK leaders. Ronald Reagan collected $30,000 for his efforts (TCM Prisoner of War) and, as we know, went on to bigger struggles against the ‘evil empire’.

Scene 5: The Bamboo Prison (Louis Seiler 1955)

Comrade-Instructor Li Ching (played by the great Chinese-American actor Keye Luke, a.k.a.Charlie Chan’s Number One Son) is trying to explain the evils of American capitalism to a scruffy, devil-may-care batch of American POWs. The topic of the day is ‘Why are we treating you so well. ‘You from underprivileged, you from oppressed, from common members of working class,’ begins his clumsy delivery. Beside him sits Sergeant Rand (Robert Francis). He has become a ‘progressive’, accepting indoctrination and becoming a teacher’s pet. The soldiers mock the instructor with an ironic version of ‘She’ll be Comin’ Round the Mountain’: ‘Oh We Never Had It So Darn Good Before,’ goes their impromptu refrain. Rand intervenes and tells the hapless Chinese instructor that the good ol’ boys are far from converted.

|

The Bamboo Prison, 1955 |

The Bamboo Prison is one of the most off-beat, almost gleefully B-grade movies made about the Korean War. Its humour had a distinctly whistling-in-the-dark quality. ‘The screenplay for The Bamboo Prison . . . was obviously influenced by Billy Wilder’s recent (and very successful) WWII comedy-drama Stalag 17’ (1953). It freely “borrows” several aspects of that film’s plot and character types, but introduces a brainwashing motivation’ (TCM The Bamboo Prison). It became known soon after the return of the POWs that the camps had indeed been miserable places: lack of medical treatment, lack of adequate food or clothing or heating, beatings and worse had combined to kill off almost half of the prisoners, from the bitter winter of 1950-51 to the repatriation process of 1953-54. To these physical conditions ‘the Chinese added a forum in which POWs could be minutely scrutinized for compliance: political education classes. These intensely monotonous sessions occupied a significant part of an average POW’s daily existence; prisoners hated them . . . Chinese political trainers also used personal autobiographies and extensive public confessions to draw people out’ (Young 1998). It seems that this process of indoctrination based on deprivation, group-think coercion and the plumbing of personal and emotional history is what lay behind the more fanciful, nightmarish claims of communist threats to the very mind and spirit of free peoples. Through the Korean experience, the ‘brainwashing issue helped to shift the concept of totalitarianism from the simple coercion of the police state to “the enslavement of the individual psyche”’ (Young 1998, citing Abbot Gleason; see also Seed 2004: 81-105).

The character Rand is in fact a false traitor and fake progressive. Like the character played by Reagan in Prisoner of War, Rand has been infiltrated into the camp to investigate abuses. As also happens in the earlier film, Rand has a nemesis among the ‘reactionary ‘prisoners who, as it turns out, is himself an infiltrated intelligence officer. Whereas Korea had sketched out fears of communist infiltration as battlefield threat, by the mid-1950s scriptwriters had reversed the polarities, and invented stealthy penetration of POW camps as a sign of resistance in a seemingly helpless situation; it was of course a good way to up the suspense level in what might otherwise seem unrelieved dreariness. But such a manoeuver could not do much to save either of these films. The patriotic spies of Prisoner of War and Bamboo Prison were distinctly unappreciated by the US military: ‘the implication that no U.S. prisoners had collaborated – except those asked to do so by Military Intelligence – was problematic’ (Carruthers 2009: 201). Not only did it inadvertently seem to confirm Chinese allegations that all US servicemen were essentially spies, but worse, it collided with the military establishment’s decision to proceed with courts martial against a number of returned POWs. As the New York Times military correspondent put it, Americans ‘”must rid themselves of sentimentality . . . and they must strive to see the prisoner-of-war issue whole” . . . civilians must accept that some “weak, maladjusted, dissatisfied and immature young men”’ had in fact acted as traitors and would have to face punishment, regardless of what they may have been through in the camps (Ibid: 202).

No Hollywood film made in this era attempted to create a realistic depiction of what the combination of physical and mental coercion can do to break a human spirit. In other words, there was certainly no Cold War equivalent to the Chung Ji-young 장지영 2012 film National Security <남영동 1985>. It re-enacted with remorseless detail water-boarding and electro-shock torture as used during the Chun Doo-hwan era.

But a few American writers did try to convey something of the experience through the means of fiction, mainly in the form of now long-forgotten novels. Francis Pollini’s hard-boiled, fragmentary narrative Night (1960) had to find its first publisher in Paris. The subsequent UK and US editions appeared with a subtitle – A Truthful Novel of the Nightmare Called Brainwashing – which jettisoned the suggestive simplicity of the main title for a brazen Cold War sales pitch (Pollini 1960; Seed 2004: 88-9). A slicker production was Sword and Scalpel (1957) by Frank G. Slaughter which, in addition to its two-dimensional characters and hackneyed romantic subplot, did at least bring a bit of skill to the court martial proceedings faced by protagonist Captain Paul Scott (Slaughter 1957).

Scene 6: The Rack (Arnold Laven 1956)

Captain Hall (Paul Newman) is being court martialed. He had been captured in January 1951. Lonely, vulnerable, he had eventually broken and agreed to co-operate with the enemy while a POW in Korea. Before then, he had thought he could outwit his Chinese mentors; he played the role of ‘progressive’ and contributed to propaganda lectures; he had used byzantine pseudo-Marxist jargon, assuming the men would get the joke. They now come to testify against him. His interrogation and autobiography had uncovered the profound guilt he felt over the sad fate of his mother and his deep resentment towards his martinet of a father, a career officer. After a long period of isolation and misery, he had crumbled when that burden of guilt was used as leverage: he would have signed anything at that point, he admits, made any statement just for a chance of a stinking blanket and some sound sleep.

The script, based on a tele-play by Rod Serling, provides a sophisticated, liberal rejoinder to B-movie humour or action plots; it treads a fine line between sympathy for the suffering of even collaborating prisoners, the need to recognise the heroism of those who held out, and the possibility that the ultimate loneliness, weakness, lies in the wider body politic of Cold War American society. ‘By mid-decade, social critics overwhelmingly construed U.S. prisoners’ record in captivity as a source of alarm, less a testament to communist brutality than an index of national collapse’ (Carruthers 2009: 201). The US Army at first took a very tough line against suspected collaborators, ‘investigating 426 men – 11 percent of returned prisoners’ (Carruthers 2009: 204). Serling’s script, along with some very fine performances from liberal Hollywood actors like Newman, expressed a serious sense of malaise, a cultural aversion towards this punitive bullying.

|

Italian poster for The Rack, 1956 |

The film was also in sympathy with liberal psychologists and social scientists, such as Albert Biderman and Robert Jay Lifton, who had criticised the myth of brainwashing, ‘especially its ”lurid mythology” as a “mysterious oriental device”. . . shaped by the “diabolical view of Communism and the racist basis of reactions”’ (Seed 2004: 48, citing Lifton, then Biderman). As Captain Hall’s defence counsel puts it, what the defendant and other POWS had encountered ‘isn’t brainwashing, it never was, no drugs were used; no attempt was made to eradicate the mind, but every attempt was made to make it suffer’. By the end of his gruelling testimony, Hall is hollowed out with grief but bearing up.

The seven officers on the panel pronounce him guilty of two charges. Before they pronounce sentence, however, the film ends. He had broken, he is legally, militarily guilty. Now what is the right thing to do with him? Serling leaves the question with the audience.

The Freudian intellectual landscape of mid-century America is prominent. In the opening scene of return, we see other soldiers coming home from Korea embraced by loving mothers and fathers; Hall’s father remains very much the Army major. And when he learns of the charges brought against this son, his reaction is vicious – he wishes that he had died over there, as his older brother had. Only to his sister-in-law is Hall able to express his painful youth, torn between a caring but ill mother and the coldness of his father.

By the era of the Cold War, the feeling was common among a wide range of social commentators that America had grown weak, that ordinary people were too easily manipulated by political propaganda of all kinds and their minds tuned to the language of advertising and the empty promises of consumer capitalism. This cultural and spiritual vacuum had failed to sustain the first post-World War II soldiers in the hands of a ruthless, highly motivated enemy.

Of course, when in doubt, you could blame the American ‘mom’. She might be a kind of undetected Freudian fifth column, a source of weakness, tying sons to emotional and psychology aprons strings for life. Philip Wylie’s notorious Generation of Vipers had sketched the threat of ‘momism’ as early as 1942.

The Rack 1956 clip — watch out, spoiler

Scene 7: The Manchurian Candidate (John Frankenheimer 1962)

Major Ben Marco (Frank Sinatra) has a recurring nightmare tied to his experiences in the Korean War. He dreams a strange world in which a tedious talk on hydrangeas at a ladies club is simultaneously a cruel demonstration of the power of brain-washing enacted by a sadistic Chinese scientist in the presence of an audience of Cold War cliché villains, East Asian and Russian. One of his men, Sergeant Shaw (Laurence Harvey), kills – or seems to kill — two of their comrades before Marco’s eyes.

|

The Manchurian Candidate, 1962 |

We first meet Shaw as a returning hero, winner of the Medal of Honor. He had rescued their squad when they were about to be overwhelmed by enemy forces, as his fellow soldiers have unanimously declared. We also meet early on Shaw’s father-in-law, an enthusiastic anti-communist, who is being managed by Shaw’s steely-souled mother towards the office of president. The noir thriller aspects of the film take the audience on Shaw’s trajectory from false hero to deadly marksman, a man pre-programmed for a political murder by ruthless Asiatic enemies and, worse still, under the hypnotic control of his castrating mother, herself in league with the communists. This is ‘momism’ at its most deadly.

In the long, complex scene above, a brilliant combination of camera work and mise-en-scène takes us inside the slippery paranoia of America on the eve of the Kennedy assassination. The Manchurian Candidate sums up many of the themes and fears of Cold War America with great panache. How the Fu-Manchu-like evil scientist managed, in only three days, to drug, hypnotise, and condition healthy GIs into committing murder of their fellows and accepting as true the planted memories of Shaw’s heroism, or how Shaw was conditioned to be ready to respond to the proper trigger and assassinate a presidential candidate – none of this is explained in the film nor is it any clearer in the original novel of 1958 by Richard Condon (Seed 2004: 106-33).

The assassination of Kennedy in November 1963 would, for a time, make paranoia seem like common sense, and impart a spooky sense of prophecy to Frankenheimer’s film. Arguably, those in America who insisted from November 1963 on seeing Lee Harvey Oswald as a communist agent wanted to perpetuate Cold War panic, hanging onto paranoia like a warm cozy blanket. To recognise that the political violence was home grown could seem a step towards leaving that mentality behind. But then right around the corner was the next Korea, the Vietnam War.

Alien invaders

Scene 7: Invaders from Mars (William Cameron Menzies 1956)

Kind family man George (Leif Erickson) goes off to investigate a strange object which has landed near his happy home. He returns utterly changed; he acts like an angry, robot-version of his ordinary self. Martian invaders seized him and, in their mysterious underground laboratory, implanted a device into his brain. Others will follow the road to alien control before a happy end is supplied.

|

Invaders from Mars, 1956 |

Scene 8: Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Don Siegel 1956)

Dr Bennell (Kevin McCarthy) and his friend Becky (Dana Wynter) by now realise that something monstrous is happening to the small community of Santa Mira, CA. People are being replaced by doppelgängers which emerge from giant seed pods. They look and sound just like normal people, but have no humanity left in them. In one scene, before they try to escape the town, they peer out of an office window and watch their ‘neighbours’ assemble in the small town square, summoned as if by telepathic signal; the ‘people’ get busy with the delivery and circulation of the pods. They witness the reality of ‘a malignant disease spreading through the whole country’. It has moved right into the centre of town and become the main business of Main Street USA.

|

Invasion of the Body Snatchers, 1956 |

In Japan, Godzilla (1954) conveyed echoes of the massive destruction of the country’s urban population by American bombs, nuclear and conventional, as well as fears over nuclear testing in the Pacific. Hollywood also used fears about radiation and atomic weapons within the new genres of science fiction. But in America perhaps the most dramatic form of sci-fi horror relied upon the Cold War discourses about infiltration and mind control which had been generated by the Korean War and its complex reprocessing in journalism and popular culture. Sci-fi paranoia and the Cold War political version often seem to have been almost interchangeable. Years after making Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Don Siegel made a thriller with Charles Bronson, Telefon (1974). Bronson has to track down a series of sleeper agents planted in the US by Soviet intelligence; they go into action automatically, triggered by a telephone message. The film makes his 1956 look like a masterpiece.

Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a very fine, creepy sci-fi noir, open to more than one interpretation. Is this an allegory for communist infiltration? Or – perhaps as likely – the nightmare vision of an American society irretrievably conformist and mindlessly in thrall to Cold War paranoia (Grant 2010: 63-76)? But I can testify to the power of Invaders from Mars, at least for those of us growing up in the era. I must have been around seven or eight when my mother took me to see it at our local cinema (long lost amid the invasion of the multiplexes). I could only keep watching the scary scenes if I crouched on my knees and peered between the seats in front, using them as a shield — just in case.

Conclusion

One reason for the differences between South Korean films about the Korean War and those produced in Hollywood arises from some fundamental, brutal geo-political circumstances. During the late-1950s and 1960s filmmakers such as Lee Kang-ch’eon, Kim Ki-deok or Lee Man-hee did successfully adapt the main lines of the Hollywood combat film, developed chiefly to represent battles of World War II, to Korean contexts, but the fit was not always easy to make. For American filmmakers, like American audiences, the Second World War had happened elsewhere: on far-flung chains of palm-fringed islands and atolls, in South-East Asian jungles, or in the battered towns and cities of old Europe. Korean people, North and South, had no such luxury of distance or exoticism when it came to their war. It had begun as a civil war of local skirmishes as early as 1946, exploded into rebellion during 1948, and with the invasion of South Korea on 25 June 1950, become a full-scale international confrontation. The see-saw nature of the fighting back and forth through cities, towns and villages of the peninsula, massacres of prisoners by elements of the Republic of Korea police, army and vigilante groups, vicious examples of local score settling, revenge taken by Northern soldiers and partisans, the dropping by the mainly American jets and bombers of more bombs on North Korea than had been used during the entire war against Japan — including a favourite new weapon, napalm — all this added up to an experience of actual, physical violence, concentrated in time and space, that has few comparisons even in the bloody history of the twentieth century (Cumings 2010).

Another differentiating factor is the emphasis in Korea-made war films on small communities and families. In particular, anti-communist war films are less concerned with depicting any generalised assault on the non-communist, ‘democratic’ political system, nor do they usually dwell on the psychological trauma of well-defined individuals. Rather, the focus is on individuals who suffer as part of families and village/neighbourhood societies. The Northern troops and partisans launch an assault on natural, proper relations and hierarchies. Peasants are turned against landlords and yangban rural elite, poor against wealthy. Friend is turned against friend; ‘natural’ Korean family relationships are perverted: brother turned against brother, son against father, etc. And mothers are protective and sheltering and, ultimately, self-sacrificing. No ‘momism’ here.

As should be clear from the examples of American films interpreted above, American panic – even as a collective, highly politicised experience — was often turned inwards. It generated fears for the threatened integrity of the individual – as physical being and psychological, even spiritual subject – who was simultaneously a most American individual. Perhaps no one has better summed up the eerie atmospherics of American Cold War paranoid political culture than historian Richard Hofstadter:

there is a vital difference between paranoid spokesmen in politics and the clinical paranoiac. Although they both tend to be overheated, oversuspicious, overaggressive, grandiose, and apocalyptic in expression, the clinical paranoiac sees the hostile and conspiratorial world in which he feels himself to be living as directed specifically against him; whereas the spokesman of the paranoid style [of politics, and I would add culture] finds it directed against a nation, a culture a way of life whose fate affects not himself alone . . . His sense that his political passions are unselfish and patriotic, in fact, goes far to intensify his feeling of righteousness and his moral indignation (Hofstadter 2008: 4).

To apply this great liberal historian’s trenchant observations on paranoid style in cultural politics to the contemporary United States or our own very disunited United Kingdom requires fine tuning. It also seems frighteningly relevant.

An earlier, shorter version of this essay was published in Korean: ‘Naengjeon paenik kwa Hanguk jeonjaeng yeonghwa: Jukjang esoeo shinchae kangtalja kkaji’ in Hanguk yeonghwa: sege-an majuchida, ed. Kim So-young (Hyeongshil munhwak 2018), pp. 91-118.

VIDEO SUPPLEMENT

Cold War Panic, brought to us at YouTube

At the time of writing (June 2020) the following videos are available on YouTube. Never discount the value of trailers. They can be extremely eloquent in packing a whole Zeitgeist into a minute of two of concentrated imagery. Ronald Reagan flogging his film Prisoner of War says much about the man and his place in the era; the trailer for Invasion of the Body Snatchers will have you headed for the hills.

Many of these films are available on generally inexpensive DVDs and/or a variety of online platforms.

Piagol complete

Rainy Days complete

Korea/One Minute to Zero complete

Prisoner of War trailer, intro by Reagan

The Rack 1956 clip — watch out, spoiler

Manchurian Candidate 1962 trailer

Invasion of the Body Snatchers trailer

Bibliography

Susan L Carruthers, Cold War Captives: Imprisonment, Escape, and Brainwashing (Univ of California 2009)

Steven Casey, Selling the Korean War: Propaganda, Politics, and Public Opinion 1950-1953 (Oxford 2008)

Bruce Cumings, The Korean War: A History (Modern Library 2010)

Barry Keith Grant, Invasion of the Body Snatchers (BFI 2010)

Charles J. Hanley and Martha Mendoza, ‘The Massacre at No Gun Ri: Army Letter reveals U.S. intent’

Richard Hofstadter, ‘The Paranoid Style in American Politics’, in The Paranoid Style in American Politics (Vintage Books 2008)

KMDb Jangma

Mark Morris, ‘War Horror and Anti-Communism’ in Korean Horror Cinema, eds. Alison Peirse & Daniel Martin (Edinburgh 2013)

Francis Pollini, Night (Calder 1960)

Tony Shaw, Hollywood’s Cold War (Edinburgh Univ Press 2007)

David Seed, Brainwashing: The Fictions of Mind Control, A study of Novels and Films Since World War II (Kent State Univ. Press 2004)

Frank G. Slaughter, Sword and Scalpel (Arrow Books 1957)

TCM Prisoner of War

Charles Young, ‘Missing Action: POW films, Brainwashing and the Korean War, 1954-1968’, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 18:1 (March 1998)