Introduction1

On 8 August 2016, Emperor Akihito 明仁天皇 (r. 1989-2019) appeared on national TV to address the Japanese people for only the second time in his twenty seven year reign.2 His first appearance was five years before in March 2011 in response to the devastation of the Great East Japan Earthquake.3 In 2016, it was the very different matter of abdication that animated him. In a performance that was all the more riveting for being understated, he informed the nation – in suitably oblique fashion – of his desire to abdicate. The problem he confronted was the law. The Imperial Household Law (Kōshitsu tenpan 皇室典範) has no provision for abdication; rather in Chapter 3 it provides for a regency in the event an emperor can no longer continue. Emperor Akihito was challenging the law, and seeking popular support for his challenge. This was a political move of the sort not permitted him under the constitution. So, it is little wonder that Emperor Akihito caused a stir.

But the emperor here was doing something more than challenge the Imperial Household Law. He was setting forth his understanding of the quality of twenty first century emperorship, as set out in the Constitution of Japan, Chapter 1, Article 1. This is the Article that identifies the emperor as “symbol of the State and the unity of the people.” Since the Constitution does not define the meaning of “emperor as symbol,” the emperor had had to come to his own conclusions. As he articulated it in August 2016, it meant nothing so much as praying for the people and being with the people. The emperor’s TV address sent shock waves across Japan, and prompted a rush of commentary about emperorship, about abdication, and, indeed, about the precarious future of the imperial line. The ruling LDP spoke up, as did all the major political parties. There were vociferous interventions, too, from the ultra-conservative Nippon Kaigi 日本会議 organization, of which Prime Minister Abe Shinzō 安倍晋三 is a member.4 The several experts, whom the prime minister subsequently consulted, let their views be known.5 Others, not directly consulted, spoke up from across the political spectrum. Some academics – but surprisingly few – also pitched in.

This author was struck by the fact that commentators gave no critical attention to the emperor’s rites of accession. After all, a careful study of the dynamic, ritual process of emperor-making in its historical context should reveal much about Japanese emperorship: what it is, what it has been and what it aspires to be. The oversight is perhaps explained by our tendency to assume princes, kings and emperors play only the most passive role in ritual events. We speak unguardedly of accession rites as if they work on a prince and make of him a king or an emperor; or that a prince undergoes such rites in order to become king or emperor. There is of course validity to this view, but only some. If we look back at the Reiwa 令和 accession rites, which extended from April 2019 through till December, we can see that the role of Naruhito, crown prince and emperor, was a dynamic one.

What Naruhito did here was construct, display and render meaningful an array of new and privileged relationships of power. The dynamic building of power relations is a universal function of ritual performances; Japanese accessions can be no exception. Three of these clearly mattered above all in 2019:

- The first saw the emperor engage with the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu Ōmikami 天照大神, with the spirits of the imperial ancestors (kōrei 皇霊), and with other assorted kami 神;

- The second had the emperor engage with the Japanese state, as represented by the heads of the three powers (sanken no chō 三権の長): the prime minister, the chief justice of the supreme court, and the speakers of the House of Representatives and the House of Councilors;

- In the third relationship, the emperor engaged with the Japanese people, “with whom resides sovereign power.”

In his August 2016 TV address, Emperor Akihito had stressed the importance of his relationship to the Japanese people, but the quality of Japanese emperorship is to be found in this multiplicity of power relations.

In this essay, I first focus on the dynamic role scripted for the emperor in the Reiwa accession drama, the better to bring these critical power relations into relief. I then take an historical perspective, and trace the roots of this emperorship back to the imperial restoration of 150 years ago, to the new accession rites invented by Meiji bureaucrats and refined in the Taisho period. It is in this Meiji-Taisho transition that the origins of the Reiwa accession are to be found. Accession rites are of key importance in understanding emperorship, but in the end, they are not everything. They shape, and are themselves shaped by, other interventions: legal, political and personal. In the final section, I return to the twenty first century to look again at Emperor Akihito’s personal and very public intervention of August 2016. I ask what it, and the reactions to it, reveal about the quality of emperorship in the 21st century.

1) Ancestors, Politics and People

We can reflect on the Reiwa accession rites as a drama in five more or less distinct acts. It was a drama because, before our eyes, a crown prince transformed himself into an emperor. As for the five acts, Act 1 was Emperor Akihito’s rite of abdication staged in the Matsu no Ma 松の間State Hall of the Imperial Palace on 30 April (Figure 1).6

Figure 1: Act 1 Emperor Akihito Abdicates

Act 2, on 1 May, saw Crown Prince Naruhito 徳仁 receive the sword and the jewel of the imperial regalia in the same ritual space, and then re-appear as Emperor Naruhito for the first time (Figure 2).7

Figure 2: Act 2 Rite of Regalia Transfer

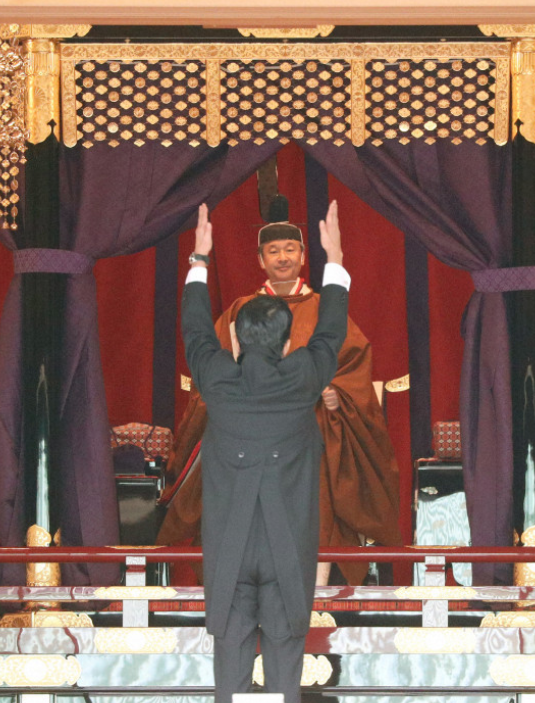

Act 3 took place six months later on 22 October in the same Matsu no Ma State Hall, when emperor and empress physically ascended their thrones, presenting themselves for the first time to the national and international community (Figure 3).8

Figure 3: Act 3 Emperor Naruhito’s Enthronement

Act 4 was the two-scene daijōsai 大嘗祭 or great rite of tasting on the night of 14-15 November, when Emperor Naruhito feasted twice with the Sun Goddess on the first fruits of the harvest (Figure 4).

The fifth and final act was a cluster of ritual events that ran from the end of November through into December. The emperor left the imperial palace with the empress, and embarked on an extended pilgrimage of imperial ancestral sites: the Ise Shrines 伊勢神宮 in Mie Prefecture; and the mausoleums of Emperor Jinmu 神武天皇 in Nara, and of Emperor Meiji and his father in Kyoto, and of Emperors Taisho and Showa in Tokyo (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Act 5 Emperor Naruhito at Ise’s Inner Shrine

Such anyway was the five-act sequence through which Crown Prince Naruhito transformed himself into Emperor Naruhito. What merits attention are the new, privileged relationships of power that he was constructing here. The first of them connected the emperor with the sacred realm: with the Sun Goddess, the spirits of the imperial ancestors, and the myriad kami of heaven and earth. In the November daijōsai, he came face to face with the Sun Goddess in the Daijō Palace (Daijōkyū 大嘗宮), a cluster of wooden buildings specially erected in the grounds of the Tokyo palace proper. On this occasion, he entered in turn the palace’s two main halls, the Yukiden 悠紀殿 and the Sukiden 主基殿. In each, he faced Ise where the Sun Goddess is enshrined, and presented to her offerings of rice, millet, and rice wine, red-snapper, horse mackerel, and abalone, chestnuts, and dried persimmons.9 In the company of the Sun Goddess, he then partook of rice, millet, and rice wine. A fortnight later, he headed to the Ise Shrines with the empress to venerate the Sun Goddess again, before touring the ancestral mausoleums in Nara, Kyoto and Tokyo. But this was by no means the extent of it.

The emperor marked every stage of the accession sequence with veneration of the Sun Goddess and the imperial ancestors. These acts of veneration took place in a ritual complex within the grounds of the imperial palace, known as the Kyūchū Sanden 宮中三殿 (Figure 6). It is a three-part, segmented sacred space, the center of which is occupied by the Kashikodokoro 賢所, the Sun Goddess’s shrine. It contains a mirror that is a replica of the one in Ise. It is flanked on the far side by a shrine for the imperial ancestors, the Kōreiden 皇霊殿. The spirits of all Japanese emperors, historical and mythical, extending back from the new emperor’s grandfather to Jinmu are venerated here. The shrine that flanks it on the near side is dedicated to the myriad gods of heaven and earth, and is known as the Shinden 神殿.

Figure 6: Imperial Palace Shrine-complex: Kyūchū Sanden

The new emperor and empress visited the site on 1 May, 8 May, 22 October and again on 4 December after completing their pilgrimage of ancestral sites. Figure 7 shows Emperor Naruhito in the Kashikodokoro on 8 May, relaying to the Sun Goddess his receipt of the regalia. The emperor moreover dispatched gift-bearing emissaries to the Ise Shrines, to the imperial mausoleums and to a selection of major shrines, to report on the emperor-making drama.

Figure 7: Emperor Naruhito Reports to the Sun Goddess his Receipt of the Regalia

The emperor’s ritual cultivation of the Sun Goddess, the ancestors and the kami is obviously of paramount importance in the twenty first century. Through his ritual actions, the emperor articulates the myth that he is a filial descendent of the Sun Goddess – why else venerate her? – that the imperial line is unbroken for all ages – hence the emphasis on the ancestral kami – and that the line is therefore sacred. There is an obvious tension here between the constitutional emperor, who derives his position from the will of the people (Constitution of Japan, Article 1), and the “Sun-Goddess-worshipping emperor.” In pre-war Japan, at least, the emperor worshipped the Sun Goddess in the daijōsai precisely because she authorized his right to rule. Prewar, of course, the myth and its ritual articulation had a public, state-determined quality. Postwar, the myth and the rites are the private concerns of the imperial family.

If the daijōsai is, after all, private why were the heads of the three branches of government in attendance? Why did the government fund the daijōsai with a budget set aside for the emperor’s public events?10 Why, indeed, did the government encourage people across Japan to submit offerings of local produce to the Sun Goddess at the daijōsai? I return to this last matter below. The point is that there remains an unmistakably public quality to the twenty-first century daijōsai and to the emperor’s worship of his ancestors.

The emperor used the accession stage to construct two other significant relationships, which are entirely secular. The first bound him to the Japanese state, in the person of prime minister, the chief justice of the supreme court, and the heads of the upper and lower houses of the diet. Under the postwar constitution, the emperor has no political power of course, but as “symbol of the state” he is an integral part of the Japanese polity. The emperor’s relationship to the prime minister loomed particularly large during the accession rites. Prime Minister Abe Shinzō addressed Emperor Akihito in the abdication rite, expressing profound gratitude for his reign. He participated in the rite of regalia transfer, and later responded to the new emperor’s inaugural address with felicitations and prayers for a long and prosperous reign. The prime minister was at the 22 October enthronement, too. Not only did he address the emperor with felicitations on this occasion, but, in a moment of drama, led the assembled in three celebratory shouts of banzai (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Prime Minister Abe Shinzō’s Banzai

(This was the cue for a unit of the Self Defense Forces stationed in Kita no Maru Park 北の丸公園, adjacent to the palace, to fire off a 21-gun salute.) The Prime Minister was also a more controversial presence at the “religious” daijōsai in November. The controversy is on account of Article 20 of the Constitution, which requires the separation of state and religion.

What then of the third key relationship which Emperor Naruhito constructed on the stage of his accession rites, his relationship with the Japanese people? As the Constitution states, it is from the Japanese people that he “derives his position”; it is of their unity that he is a symbol. On 1 May, a national holiday, Emperor Naruhito delivered an inaugural address in which he spoke in this way about the people:

I swear that I will act according to the Constitution and fulfill my responsibility as the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people of Japan, while always turning my thoughts to the people and standing with them. I sincerely pray for the happiness of the people and the further development of the nation as well as the peace of the world.11

It is noteworthy that he speaks here not directly to the people in the second person, but about the people in the third person. What he said was, anyway, directed at the people for their benefit through electronic and digital media.

On 4 May, he and the empress appeared on the balcony of the Chōwaden 長和殿 palace building to greet crowds of well-wishers (Figure 9). This was broadcast live to the nation on TV and the internet, as was the enthronement of 22 October, another national holiday.

Figure 9: Emperor, Empress and Imperial Family on the Chōwaden balcony

Again, the emperor spoke of his concern for the people. On this day, the government informed 550,000 convicted criminals that their slates were wiped clean.12 The emperor’s celebratory parade, delayed because of typhoon damage, finally took place on 10 November. With the empress, he rode in an open-top car west across Tokyo from the palace to Akasaka 赤坂. The parade exposed the couple – and the prime minister who also took part – to the view of hundreds of thousands of well-wishers. Millions more watched on TV and the internet (Figure 10).

Figure 10: The Celebratory Parade from the Palace to Akasaka

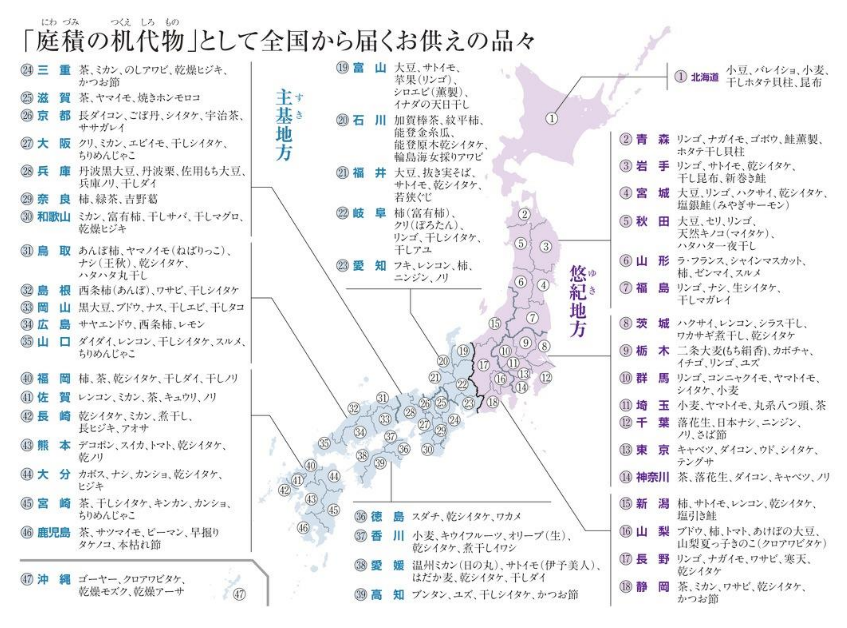

At the November daijōsai, too, the emperor connected with the Japanese people. Farmers and fishermen from across Japan were invited to submit local produce as offerings to him and to the Sun Goddess. Figure 11 maps the produce submitted from different regions of Japan. Farmers in the more rural parts of Tokyo, for example, sent rice, cabbage, radishes, udo salad plants, and mushrooms. Kyoto farmers offered rice, potatoes, tea, and millet. All of this freshly harvested produce was set before the two pavilions of the Daijō Palace on the night of 14 November.13

Figure 11: Regional Offerings Placed before the Yuki and Suki Halls of the Daijō Palace14

Select scenes from the daijōsai were broadcast to the nation on the media, and once the feast was over, the Daijō Palace was opened for public viewing before it was dismantled (Figure 12). In brief, the emperor engaged with the Japanese people in every act, if not quite every scene, of the accession drama.

Figure 12: The Daijō Palace, 25 November 201915

Such then are the key privileged relationships which the emperor constructed at his accession: with the Sun Goddess and imperial ancestors, with the Japanese state, and with the Japanese people. It is in these relationships that the essence of twentieth first century Japanese emperorship appears to inhere. The function of ritual everywhere is not only to articulate relations of power, but to root them in remotest antiquity beyond dispute. The Reiwa accession rites were typical in this regard: they sought to persuade us that Japanese emperors had since ancient times been defined by their relationship to the Sun Goddess, to the state and to the people. In this endeavor, they were it seems successful.16 In fact, however, it is only in recent history that these relationships came to inform Japanese accession rites, and so shape Japanese emperorship. They first emerged at the Meiji Restoration in the mid nineteenth century.

2) The Modern Experience

i. The Meiji Revolution

Figure 13 depicts the Shishinden 紫宸殿 Enthronement Hall and garden, located in the southern sector of the imperial palace complex in Kyoto.

Figure 13: Emperor Meiji’s Enthronement17

The date is 12 October 1868, and the event is the enthronement of 15-year old Mutsuhito 睦仁. Crown Prince Mutsuhito had received the sword and jewel of the regalia on the death of his father, Emperor Kōmei 孝明天皇 (r.1846-1867) just before the Restoration, some eighteen months earlier. This enthronement took place nine months after the Restoration. The daijōsai, by the way, would be staged fully three years later in the new capital of Tokyo. These, anyway, were the three distinct acts in the accession drama of Japan’s first modern emperor: Act 1 Regalia transfer (Kyoto; 13 February 1867); Act 2 Enthronement (Kyoto; 12 October 1868), and Act 3 Daijōsai (Tokyo; 28 December 1871).

Most striking about this enthronement scene in Figure 13 are the ritual participants. On the eastern side of the garden (right of the picture) close to the hall steps sits the new government’s president, Iwakura Tomomi 岩倉具視 (1825-1883). Beside him, are the ministers of foreign affairs, of the navy and army, of finance and domestic affairs. Senior and junior councilors and provincial governors sit directly opposite them on the western side (center picture). Kyoto-resident daimyo and warrior cohorts sit further south on the east side. This therefore is a thoroughly politicized space. Just visible at the foot of the Shishinden steps is a large globe. It rained on the day of the enthronement so the emperor never got to tap the globe with his foot. But the intent was clear: the modern Japanese emperor was not to be confined within the walls of the Kyoto palace; he was a new sovereign for a new Japan in an age of international politics. The contrast with premodern enthronements, entirely private affairs of the Kyoto court, attended only by imperial princes, courtiers and ritualists, could not be sharper. But politicization was not the only innovation.

There is a powerful new, sacred dimension to the proceedings here. Pre-Meiji enthronements were of course sacred events, too, but their quality was very different. Twenty years earlier, on 31 October 1847, the Meiji emperor’s father, Kōmei, had proceeded to the Shinshinden Hall, clad in Chinese court attire of vermilion, wearing on his head an elaborate gold crown bedecked with jewels, reciting sacred Buddhist words as he formed his hands into Shingon mudra. As he ascended the throne, he merged his human body with the body of the Great Sun Buddha. The Shishinden garden on this momentous day was filled with the fragrance of incense, which carried to heaven tidings of his enthronement; its space was arranged according to yin yang principles, and populated by courtiers similarly clad in Chinese attire.

The substance of the sacred at the Meiji enthronement was of a different order. Adjacent to the Shishinden on its east side, but structurally removed from it, is a small shrine called the Naishidokoro 内侍所, dedicated to the Sun Goddess. The shrine is as old as the palace itself but, to the best knowledge of this author, no early modern emperor ever worshipped there. The shrine anyway had no place in pre-Meiji enthronements. Yet, on the morning of 12 October 1868, the Meiji emperor proceeded first to this Naishidokoro shrine, to make offerings to the Sun Goddess. And at the very same time, imperial emissaries were at the Ise Shrines, at the mausoleum of Emperor Jinmu in Nara, and at a selection of imperial ancestral sites across the city of Kyoto making offerings on his behalf. This flurry of ancestor-oriented ritual activity was entirely without precedent.18

The Meiji enthronement was not only politicized, and rendered newly sacred. It was “popularized” too, albeit to an extent limited by the civil war. The Restoration government declared the enthronement day a national holiday and, immediately after the rite, opened the Shishinden and its garden up to the citizens of Kyoto. But the key technique deployed to engage people with the new emperor was a temporal one: the government switched the era name. The enthronement of the new emperor marked the moment at which the Meiji period formally began. Time, for all Japanese, now became imperial time. It was to be recalibrated at accessions, and measured by the span of emperors’ reigns. This was entirely new.19

Meiji’s enthronement was new in conception, then, newly scripted and newly staged. The decisive difference from premodern models was precisely that the emperor used it to construct privileged relations of power with the Sun Goddess and his ancestors, with the modern state and with the people. The man responsible for it all was Fukuba Bisei 福羽美静 (1831-1907) (Figure 14).

Fukuba, who deserves to be better known, was a nativist scholar from Tsuwano 津和野 domain. Tsuwano shared its western border with Chōshū 長州 domain in the west of the main island of Honshū. The two domains worked closely together on the eve of the Restoration. Chōshū leaders like Kido Takayoshi 木戸孝允 (1833-1877) were among the most influential in the new government, and it was Kido who brought Fukuba on board to run the government’s office for ritual and religious affairs. Fukuba was responsible for the Shinto-Buddhist separation edicts published earlier in the year, and for shrine policy more generally.20 He helped shape the new government’s policy on Christianity, and even now he was fashioning a modern ritual program for the imperial court.21 This same Fukuba Bisei assumed charge of modern Japan’s first daijōsai. He ensured that, like the enthronement that preceded it, the daijōsai was suitably staged to meet the needs of a modern emperor in an international age.

ii. The Meiji Daijōsai

Immediately after his enthronement in autumn 1868, the emperor and his government uprooted from Kyoto and relocated east to Tokyo, which duly became Japan’s new imperial capital. The first daijōsai of the modern era took place in the grounds of Tokyo Castle on the night of 28 December 1871, three full years after the enthronement. The Meiji government had abolished the feudal domains, restructured the administration under a revamped Great Council of State (Dajōkan 太政官), over which the new emperor now presided, at least in theory. In brief, Japan had by the end of 1871 laid the foundations for a modern centralized state under a new, emperor-centered government. The emperor’s performance of the daijōsai in the new capital gave to the rite an unprecedented political quality; to the city itself it lent the character of sacred center. Figure 15 is an image from a later generation, but it accurately recreates a key moment from the event.

Figure 15: Daijō Palace, Tokyo, 187122

The emperor, visible in robes of pure white, has just left the Kairyūden Hall 廻立殿, where he purified himself (right of picture). He now makes his stately way toward the Yukiden Hall 悠紀殿 (center left) where he will feast with the Sun Goddess on rice, millet and wine. Before dawn, he will eat with her once more, in the adjacent Sukiden Hall 主基殿. What the image conceals is the presence of senior political leaders: Prime Minister Sanjō Sanetomi 三条実美 (1837-1891), who has proceeded ahead of the emperor; and Saigō Takamori 西郷隆盛 (1828-1877), Etō Shinpei 江藤新平 ( 1834-1874), Terajima Munenori 寺島宗則 (1832-1893), Ōkuma Shigenobu 大隈重信 (1838-1922) and a bevy of other senior counsellors and ministry chiefs, who followed him.23 The emperor enters the Yukiden Hall; the prime minister and other government leaders remain outside. They wait in silence while the emperor feasts with his great ancestress, the Sun Goddess.

Fukuba Bisei politicized the daijōsai, then, just as he had the enthronement of three years earlier. He also made it accessible to the Japanese people as never before. In early December, the Meiji government issued to the realm a public notice (Daijōe kokuyu 告諭), probably penned by Fukuba, explaining the daijōsai; it declared a national holiday, too; and it then opened up the Daijō Palace for public viewing after the event. The public notice, distributed across the realm, situated the daijōsai as a celebration of the Sun Goddess, and of her legitimation of imperial rule. It made the point that the emperor receives his right to rule from her, and not from the military men who had overthrown the Tokugawa, nor of course from the common people. The notice concluded by declaring three days of national holiday, “in order that people might head to their local shrines to thank the Sun Goddess for her blessings.”24 In the new capital of Tokyo at least, there is evidence of widespread merry-making.

iii Taisho Evolution

Meiji the Great, as the emperor came to be known, died in 1912. He had presided over the dramatic transformation of Japan from a decentralized, feudal state into a modern nation state with a constitutional monarchy. He was succeeded by his son, Yoshihito 嘉仁 (r.1912-1926), the man known to history as Emperor Taisho. Yoshihito was the first to ascend the throne under the terms of the Meiji Constitution of 1889. And as we shall see, his accession rites in 1915 evolved to accommodate the fact he was a constitutional monarch. Taisho’s enthronement was further fashioned by two new bodies of law: the Imperial Household Law (Kōshitsu tenpan) of 1889 and the Accession Ordinance (Tōkyokurei 登極令) of 1909. Of their many stipulations, three had immediate implications for the staging of the accession drama:

- The enthronement and the daijōsai would take place not in the modern capital city of Tokyo but in the ancient imperial center of Kyoto (Imperial Household Law, Chapter 2). As a result, emperor, prime minister and the entire Japanese government relocated to Kyoto for the duration, along with the diplomatic community. Kyoto became – albeit fleetingly – the political center of modern Japan.

- The enthronement was coupled directly now, for the first time, to the autumnal daijōsai (Accession Ordinance, Article 4). Emperor Taisho’s enthronement and daijōsai were both held in Kyoto within the space of four days in November 1915. Yoshihito had received the regalia immediately upon the death of his father back in July 1912.

- Now for the first time, there was to be a key ritual role for the empress. (Accession Ordinance, Article 11). Empress Teimei 貞明皇后 was in the end absent from the accession owing to her pregnancy, but the idea that emperor and empress should both participate in the accession rites was now established.

In Taisho, no single figure influenced the enthronement in the way that Fukuba Bisei had done in early Meiji. Rather, the Accession Ordinance provided for a Board of Accession Experts, known as Taireishi 大礼使 (Articles 5, 7, 10 and 12). It was headed by Prince Fushimi 伏見宮貞愛親王 (1858-1923); its de facto leaders were Hosokawa Junjirō 細川潤次郎 (1834-1923) and Itō Miyoji 伊東巳代治 (1857-1934). The board was responsible to the prime minister, and bureaucrats from every ministry in the government –Foreign and Home, Finance, Transport, Army and Navy – were seconded to it. There was an unprecedented mobilization of state power behind the Taisho accession.

Japan in the 1910s was after all a modern nation-state with a thriving economy, a powerful military, and an external empire incorporating Korea, Taiwan and Sakhalin. Japan was a major player on the international stage, bound to Great Britain in the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, and was presently at war with Germany. Domestically, though, rapid industrialization had led to profound social upheaval. Socialism was taking root, and the movement known as Taisho Democracy was gathering momentum. All of this impacted on the rites of accession and, indeed, on the new emperor’s reign. In what follows, I am concerned with the strategies deployed by the government to develop those three definitive relationships of power: with the Sun Goddess and the imperial ancestors, with the state and with the Japanese people.

Figure 16: Enthronement Hall, Kyoto 191525

The Shishinden Enthronement Hall and garden of the Kyoto Palace, decked out for the performance of 10 November 1915, can be seen in Figure 16. The hall is essentially the same as it was fifty years before at the time of Meiji’s enthronement. It has, though, been thoroughly refurbished, and has acquired a magnificent new porch for the emperor’s motorcars. What is entirely new is the structure adjacent to it on its eastern side. This is the Shunkōden 春興殿 or Spring Hall (Figure 17). It stands where the old Naishidokoro used to be, and like the Naishidokoro, it is a ritual space for imperial acts of worship. The Sun Goddess had accompanied Emperor Taisho on his train journey from Tokyo to Kyoto; and this was her temporary abode. What is striking about the Shunkōden is that it was designed as a public space. It was built to accommodate 1,000 ritual participants. So, on the morning of 10 November 1915, when the new emperor duly entered the Shunkōden to worship the Sun Goddess, he did so in the presence of Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu, his cabinet, prefectural governors and many other dignitaries, including ambassadors and their wives from eighteen nations. And as the emperor worshipped here, so were his emissaries making offerings on his behalf at the Ise Shrines, and at ancestral mausolea in Nara and Kyoto, and at major state shrines across the land.

Figure 17: Shunkōden (Spring Hall) November, 191526

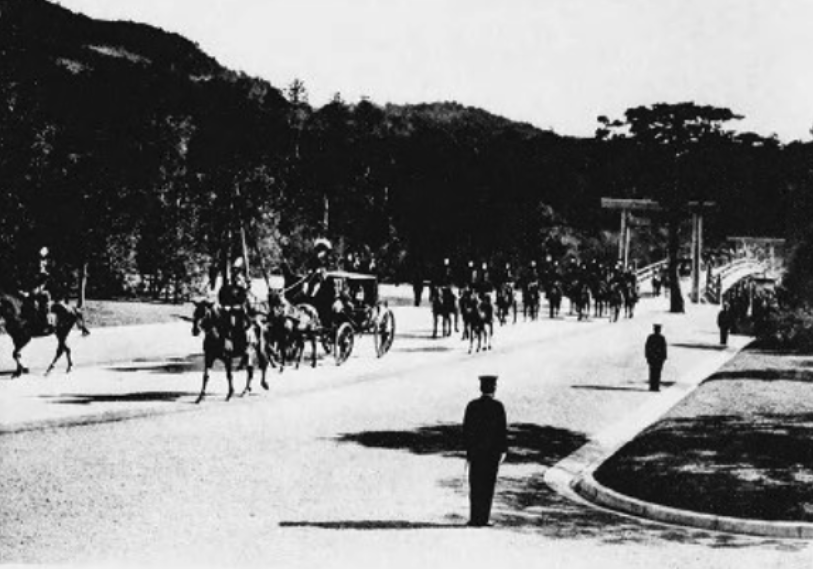

The emperor encountered the Sun Goddess again, of course, in the daijōsai just four days later on 14 November. She featured once more on 20 November, in an entirely new accession act (Act 4), which saw the emperor leave Kyoto on an historic pilgrimage to Ise. There he faced the Sun Goddess, and worshipped her (Figure 18). He returned to Kyoto the next day, before setting off to Emperor Jinmu’s mausoleum in Nara, and then the mausoleums of Emperor Meiji, and his father, grandfather and great grandfather. At each site, he performed acts of filial veneration, which were styled shin’etsu 親謁 or “intimate audiences.” Emperors’ post-enthronement pilgrimages are one of several Taisho period innovations.

Figure 18: Emperor Taisho Crosses the Uji Bridge in the Inner Shrine Precinct, Ise, December 191527

The Taisho enthronement bound the new emperor to state power in innovative ways, too. The elderly prime minister, Ōkuma Shigenobu, was scripted a leading role here. Ōkuma is just about visible in Figure 19, clad in ancient court attire, standing before the steps leading up to the Shishinden Hall. He recites a congratulatory address, and then leads the assembled audience of some 3000 Japanese and foreign dignitaries in three shouts of banzai, or “Long Live the Emperor!”

Figure 19: PM Ōkuma in the Shishinden, 10 November 191528

This too was a moment without precedent. And then Prime Minister Ōkuma featured at the daijōsai, as indeed he had done more than four decades before in 1871. The prime minister and his cabinet, accompanied by hundreds of Japanese and foreign dignitaries, later attended a succession of state banquets in Nijō Castle 二条城 personally hosted by the emperor. But the most striking aspect of Emperor Taisho’s engagement with state power concerned the deployment of the armed forces in a new and final fifth accession act. After all, the emperor was commander-in-chief of the army and navy under Article 11 of the Meiji Constitution.

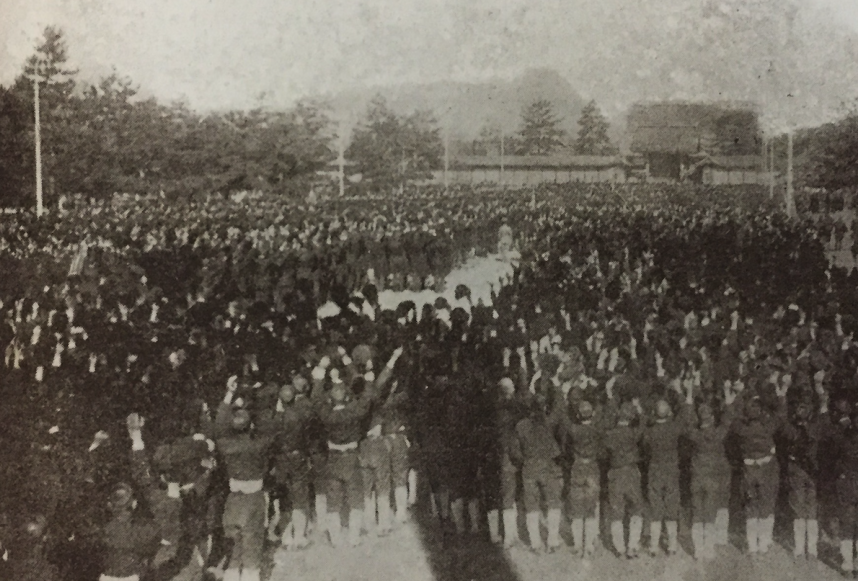

After completing his ancestral pilgrimage at the end of November, the new emperor returned to Tokyo. On 2 December, he progressed from the palace to the Aoyama Parade Ground 青山練兵場 where he presided over the largest military review ever held in Japan (Figure 20).

Figure 20: Imperial Review of Troops, December 191529

The review, styled “Tairei kanpeishiki” 大礼観兵式, comprised 40,000 troops, 5,000 horses and 200 field guns. 150,000 spectators turned up to watch, as the emperor – accompanied by imperial princes and foreign military attachés – inspected the serried ranks of soldiers, before receiving their salute. The highpoint was a fly-past by aircraft of the new army air corps. The very next day, the emperor progressed to Yokohama, where he boarded the warship Tsukuba 筑波, and oversaw a naval review of unprecedented scale (Figure 21). The review, styled Tairei kankanshiki 大礼観艦式, saw the deployment of 125 ships of war – cruisers, destroyers, minesweepers and submarines – weighing in at some 600,000 tons. Emperor Taisho finally transferred to the battleship Fusō 扶桑, where he hosted a banquet. The Fusō, launched just a month before, was a dreadnought-class vessel, armed with 12-inch guns and propelled by steam turbines. It surpassed anything in the Royal Navy at the time. A fly-past by aircraft of the new fleet air arm brought the naval review, and the entire accession spectacle, to a dramatic close.

Figure 21: Imperial Review of the Fleet, December 191530

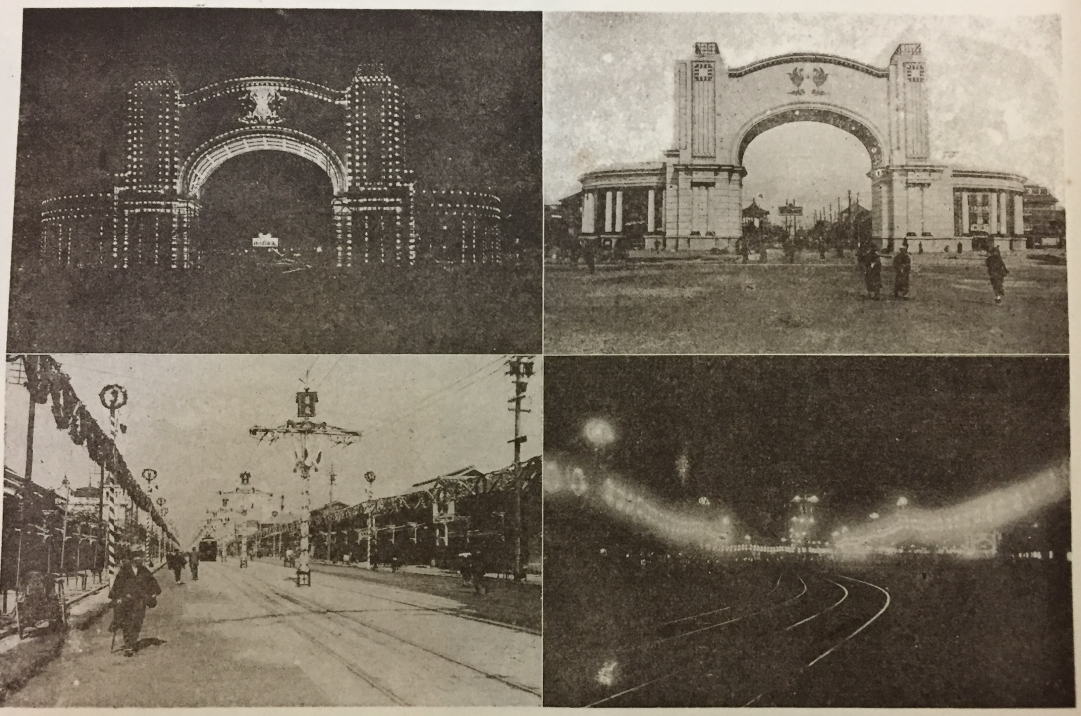

The Taisho enthronement of 1915 was notable, too, as the first in which the emperor engaged fully with the common man, woman and child. The press was proactive here. The major newspapers published between them hundreds of articles on the accession, edifying readers with the minutest details of ritual sites, ritual performance and ritual meaning. The Education Ministry’s role was crucial, too. By 1915, 70% of all children of primary school age were attending school. The ministry assured that no child in its care remained ignorant of the accession, and it duly published an official guide for teachers, which it distributed throughout the land. A principal purpose of the Tairei no yōshi 大礼の要旨, as the guide was styled, was to relate for children’s edification the story of the emperor’s descent from the Sun Goddess and his love for his subjects.31 Kyoto Prefecture and Kyoto City played their part, too. They hosted an Enthronement Exposition from early October to entertain and, of course, to edify citizens and the hundreds of thousands of visitors who descended on the city (Figure 22).32

Figure 22: The Kyoto Enthronement Exhibition, 191533

And ahead of the new emperor’s arrival, they transformed the entire city into a vibrant, celebratory space (Figure 23).

Figure 23: The Celebratory Spaces of Kyoto34

We saw that Prime Minister Ōkuma Shigenobu had stood before the emperor and feted him with three shouts of banzai. This was a moment of especial significance in the emperor’s engagement with his subjects. For, as he led the assembled guests in the banzai at exactly 3.30pm on 10 November, the 150,000 or so people packed into the palace grounds, and along adjacent streets – many of them school children – chimed in with their own banzai (Figure 24).

Figure 24: Crowds outside the Kenreimon Gate shout Banzai35

Not just in Kyoto but throughout Japan, and overseas in Japan’s colonies too, people young and old gathered in government offices, factories, companies, banks, schools and at shrines to join the banzai chorus. On this day, in many parts of Japan there were also celebratory sports meets, torch-lit processions, fireworks and lectures. All was made possible by the fact that 10 November was declared a national holiday. Other innovative techniques were deployed, too. There was, for example, a nation-wide amnesty of convicted criminals, which meant that in the city of Kyoto, where the enthronement took place, 1000 men and 50 women had their sentences quashed or reduced. The emperor also made a gift of one million yen for disbursement to men and women of over 80 years old throughout the empire.

The daijōsai, too, was the focus for popular engagement. We have seen that the Daijō Palace complex features two main halls, the Yukiden Hall and Sukiden Hall. The two halls represent the two different regions of Japan in which the ritual rice and millet are harvested. In 1915, those regions were Kagawa Prefecture 香川県, west of Kyoto, and Aichi Prefecture 愛知県, east of Kyoto. The Taishō innovation was to invite farmers and manufacturers from all over Japan, and from the colonies too, to offer local produce to the emperor and the Sun Goddess. So, for example, Kyoto producers supplied rice, soy beans, sweet-fish, turnips, potatoes, and chestnuts. From Korea, there was dried abalone, cabbages, pears and apples; from Taiwan dried bonito, citrus buntan, and bananas, and from Sakhalin, dried cod, seaweed, and potatoes. All this produce was set out before the Yukiden and Sukiden Halls. As we have seen, this technique of engaging the emperor with people through their offerings of local produce at the daijōsai continues to this day.

There was a solemn, somber mood in Kyoto on the day of the daijōsai, but thereafter celebrations resumed. When the emperor hosted “accession banquets” at Nijō Castle on 16 and 17 November, vast crowds lined the streets to watch him and the imperial princes, prime minister, cabinet members and assorted dignitaries Japanese and foreign, make their way in horse-drawn carriages to the castle. 16 November was in fact a day of banqueting throughout the Japanese empire. And then, on 1 December, the ritual sites, that is the Enthronement Hall and garden, the temporary wooden buildings of the Daijō Palace, and the banqueting halls of Nijō Castle were all opened up for public viewing. They remained open for five full months, and are said to have received over 2.5 million visitors.36

3) The Emperor’s Abdication

For all the genuine rejoicing in autumn 1915, Emperor Taisho’s reign was short and troubled. Just nine years into his reign, he succumbed to mental illness and withdrew from public life, relinquishing state functions to his son, Hirohito 裕仁. The emperor died in 1926, and Hirohito immediately received the regalia.37 The era name changed to Showa. Then, in 1928, the man known to history as the Showa Emperor (r.1926-1989) performed both the enthronement and the daijōsai in Kyoto, just like his father before him. Indeed, in every important regard, the Showa accession rites followed the precedent of Taisho.

Just a decade into the new emperor’s reign, Japan waged war on China; then came war in the Pacific. Defeat and occupation were the consequences. The US-led occupation quickly imposed on Japan a new constitution, and the new constitution sought to transform the quality of Japanese emperorship for a second time in less than three generations. The US was intent on using the Showa emperor even as it curbed his powers. The new SCAP-approved emperor was no longer sacred or inviolable; he was neither head-of-state, nor commander of Japan’s armed forces. The constitution defined him as something quite new and different. He was “symbol of the state and of the unity of the people,” deriving his position from the will of the people “in whom resides sovereign power.”38 Emperor Akihito was the first to succeed to the throne under this new constitution. His accession rites, held in Tokyo from 1989 through 1990, were duly re-scripted and re-produced to account for the postwar change. So, what changed and what remained the same?

The emperor’s three critical relationships – with his ancestors, with the state, and with the people – survived into the postwar accession rites and so into postwar emperorship. The people are no longer subjects of a sovereign emperor, of course; the people are now sovereign. But there is a striking ritual continuity in, say, the orchestration of people’s engagement with the emperor through the offerings of local produce in the daijōsai. The state, for its part, is no longer headed by the emperor; it is now symbolized by the emperor. And yet there is vital ritual continuity in the presence of the heads of the three branches of government and, in particular, in the role of the prime minister. He is a key player at the regalia transfer, at the enthronement, and at the daijōsai. The sacred, too, has remained integral to the accession rites of the postwar emperors. The newly enthroned emperor’s veneration of the Sun Goddess, of his ancestors and of the myriad kami constitutes the most obvious ritual continuity with prewar accession rites. The allegedly private status of the postwar daijōsai is seriously compromised by state involvement and indeed public participation. In other words, for all the genuine constitutional change in the quality of emperorship, there is much ritual continuity.

The accession rites of Naruhito in 2019 followed those of his father precisely, except in one vital aspect. They began not with the state funeral of a deceased emperor, but with newly construed rites of abdication. The abdication was the outcome of Emperor Akihito’s personal intervention in August 2016. Here I want to reflect briefly on the repercussions of this intervention for emperorship. The intervention, as we saw, took the form of an unprecedented plea by the emperor for popular understanding. The emperor’s TV address was a challenge to the Imperial Household Law, which denied him the right to abdicate (Figure 25). The emperor also offered his audience a new reading of emperorship, as set out in the Constitution of Japan. In the absence of constitutional clarity, he had struggled with the meaning of “symbolic emperor” in Article 1, but had finally reached the conclusion that, “[His] first and foremost duty [was] to pray for [the] peace and happiness of all the people.” He insisted, with still greater conviction, on his need to “stand by the people, listen to their voices, and be close to them in their thoughts.” It was his role to nurture “deep understanding of the people,” and “an awareness of being with the people.” These were the qualities demanded of a symbolic emperor.

Figure 25: Emperor Akihito delivers his address to the nation, 8 August 2016

Both in his challenge to the Imperial Household Law and in his reading of the constitution, the emperor was pitting himself against the administration of Prime Minister Abe Shinzō. We know that, in autumn 2015, Emperor Akihito had informed the prime minister of his wish to abdicate, and proposed raising the matter at his birthday press conference in December. The proposal did not meet with prime ministerial approval, however, and the emperor’s frustration grew. In July 2016, he sidestepped the prime minister, and directed the Imperial Household Agency to inform NHK of his determination to step down. When NHK broadcast the scoop to the nation on the night of 13 July, the PM’s office was caught completely unawares. Overwhelming popular support for the emperor forced the prime minister’s hand, and he duly convened a council of experts to debate the options. They were two-fold: either a one-off bill enabling Akihito to abdicate; or reform of the Imperial Household Law to allow abdication for all emperors. The prime minister and the LDP preferred the former; the emperor was known to favor the latter.

If the truth be known, Prime Minister Abe and his government did not support abdication; they wanted the emperor to stay put, and hand over burdensome tasks to a regent, as provided for in the Imperial Household Law. They were wary, too, of tampering with that law, not least because it would refocus attention on the fraught issue of the imperial line’s future, and the paucity of male heirs. Chapter 1 of the law sanctions succession by males only, and there are just three eligible males. With regard to abdication, the Kōmeitō, the LDP’s partner in government, toed the LDP line, opting for a one-off law. The opposition parties on the whole favored inserting a new abdication clause into the Imperial Household Law. Minshintō Secretary General Noda Yoshihiko, was adamant that now was the time to legalize abdication for all emperors. The Shamintō concurred on the grounds that emperors’ human rights were at stake. This position was shared by the Seikatsu no tō and the Communist party.39 But on this matter, the government had its way. On 16 June 2017, it passed a special bill allowing abdication for Akihito alone.

In the end, abdication could not be uncoupled from the broader issue of succession. Indeed, the law carried a supplementary resolution (futai ketsugi 付帯決議) promising a full debate on the future of the imperial line, as soon as the rites of accession were complete. At the time of writing, a year after the transfer of regalia, and six months after the daijōsai, the promised debate has yet to take place. However, in the wake of the daijōsai, the media pressured the government and the opposition parties to declare their respective positions on how best to secure the imperial line’s future. A brief survey of those positions will suffice to show that the quality of Japanese emperorship remains contested.

Nikai Toshihiro 二階俊博, secretary general of the LDP, opined that in a democratic society like Japan’s, where equality between the sexes obtains, the obvious solution is female succession. In an age of “respect for women,” we can make no exception for the imperial family, he insisted in November 2019.40 This proves to be a minority view within the LDP, however. There are, of course, two “empress options,” and it is not clear whether Nikai advocates both. One involves succession of a woman, descended from a male emperor, to the throne for a single generation (josei tennō 女性天皇); the other, longer term option involves the succession of the offspring of an empress and her commoner husband (jokei tennō 女系天皇). There is ample historical precedent for the former, but none for the latter. Deputy Prime Minister Asō Tarō 麻生太郎 spoke for the LDP majority when he declared it “inconceivable” that the throne could ever be occupied by someone not descended from a male emperor.41 The LDP solution is to “reactivate” the collateral families abolished during the occupation.42 Five young members of these families are presently alive, it is true, but to date not one has expressed a desire to return to the imperial fold.43

There is also the related issue of “female collateral families.”44 At present, a princess must leave the imperial family when she marries a commoner (Imperial Household Law, Chapter 2 Article 12). One proposal much discussed in the media, and debated by opposition parties, is to allow princesses married to commoners to remain within the fold as heads of new female collateral families. There are two implications to the proposal: 1) it would mean no further reduction in the number of princesses available to perform public duties, and would therefore lighten the burden all round; 2) male offspring of the princess’s marriage to a commoner would be eligible to succeed, thus increasing the pool of heirs to the throne. The Abe administration is opposed to the female collateral family initiative precisely because it opens the door to succession by the offspring of an empress and a commoner. Where do the opposition parties stand?

Kōmeitō, Kokumin minshutō and Nihon Ishin no Kai are all well-disposed to the succession of women to the throne, but only if the woman is the daughter of an emperor. A majority in each party opposes the idea of the offspring of an empress succeeding.45 The Rikken minshutō presents a 90% majority in support of women succeeding, but that majority drops to (a still substantial) 68% when it comes to allowing offspring of an empress and a commoner to succeed. The Communist party and the Shamintō have no problem with either of the “empress options,” so long as public opinion is with them.46 Public opinion is certainly on their side. Recent polls suggest that over 70% of the public support both empress options. Active support for the creation of “female collateral families” is to be found in the Rikken minshutō, the Shaminto and the Communist Party. Kokumin minshutō and the Ishin no Kai meanwhile are both happy to participate in debates on this matter.47

Conclusion

The Japanese imperial line is the oldest, continuous hereditary monarchy in the world. The secret of its longevity is that it has adapted – it has had to adapt – to the many and varied demands of state and society. Over the centuries, the imperial line has been buffeted by frequent change. No change was greater than that forced upon it in the nineteenth century Meiji Restoration. After the restoration, Japanese emperors became the “pivot” of the modern Japanese nation-state, “pivot” being a word much favored by Meiji period bureaucrats. Modern emperors were sovereigns to their subjects. They were men of politics, expected to advise, encourage and warn politicians of the day. They were theoretically at least commanders-in-chief of the modern Japanese military. They were also the most persistent and persuasive purveyors of the story of their descent from the Sun Goddess, and of the sacred unbroken imperial line.

This sacred quality of emperorship was first articulated in the accession rites of Emperor Meiji in 1868 and 1871. It received legal underpinning in the Meiji Constitution of 1889, and was refined by the Imperial Household Law of 1889 and then the Accession Ordinance of 1909. It found legitimation above all in the accession rites of the Taisho emperor in 1915 and the Showa emperor in 1928, and it flourished until 1945. And then, for a second time in much less than a century, there was another radical reconfiguration of emperorship. The 1946 Constitution determined that Japanese emperors were no more the nation’s pivots, or heads of state, or commanders-in-chief; they now engaged with the state as its symbol; and with the people as symbol of their unity, whatever that meant in practice. But the story of emperors’ descent from the Sun Goddess, and of the unbroken line endured, not least in the emperor’s ritual performances. Postwar emperors have continued to bear ritual witness to this sacred quality of emperorship.

The Reiwa accession intimated that emperorship is shifting again. Japanese emperors can now abdicate. The 2017 abdication bill was a one-off, it is true, but legal precedent has been set. The problems of imperial succession suggest that further radical change is in the offing. There are at present three men in line to succeed. In order they are: 1) Emperor Naruhito’s 54-year old brother, Crown Prince Akishino; 2) the crown prince’s 14-year old son, Prince Hisahito; and 3) Prince Hitachi 常陸宮, the 83-year old brother of Emperor Emeritus Akihito. For reasons of age, Hisahito is the most likely of the three to succeed. Whether or not he will produce a male heir is unknowable, but there is surely a significant chance that an empress will have to ascend the throne in a generation or two. The Japanese people are overwhelmingly supportive of the idea. Were it come to pass, it would constitute another decisive shift in the quality of 21st century Japanese emperorship. The corona virus has put on hold for now the promised debates, but this author, for one, waits with bated breath for their commencement.

References

Breen, John. “Ideologues, bureaucrats and priests: on Buddhism and Shintō in early Meiji Japan.” In Shintō in history: ways of the kami (co-edited with Mark Teeuwen). Hawaii University Press, 2000, pp.230-251.

Breen, John and Mark Teeuwen. A new history of Shinto. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Breen, John. “Abdication, Succession and Japan’s Imperial Future: An Emperor’s Dilemma.” Japan Focus, 17:9, 3 (2019).

Ichida Ofusetto Insatsu Gōshi Kaisha Tōkyō Shiten ed. 市田オフセツト印刷合資会社東京支店編. Go tairei kinen shashinchō 御大礼記念写真帖. Nihon Denpō Tsūshinsha, 1915.

Itō Yukio 伊藤之雄. Kyōto no kindaika to tennō: gosho o meguru dentō to kakushin no toshi kūkan 1868-1952 京都の近代化と天皇:御所を巡る伝統と革新の都市空間. Chikura Shobō, 2010.

Kunaishō Rinji Teishitsu Henshūkyoku 宮内省臨時帝室編修局 ed. Meiji tenno ki 明治天皇紀 1. Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2000.

Fukuba Bisei 福羽美静. “Sokui shinshiki shō” 即位新式抄. In Itō Hirobumi 伊藤博文 ed. Hisho ruisan (25) 秘書類纂(第25巻). Hisho Ruisan Kankōkai, 1936.

Kyōto Fu 京都府. Taishō tairei Kyōtofu kiji: Shomu no bu ge 大正大礼京都府記事 庶務の部下. Kyōto Fu, 1917.

Monbushō ed. 文部省編. Tairei no yōshi. 大礼の要旨. Monbushō, 1915.

Miyachi Masato 宮地正人. “Tennōsei ideorogī ni okeru daijōsai no kinō: Jōkyō no saikō yori konnichi made” 天皇制イデオロギーにおける大嘗祭の機能:貞享の再興より今日まで. Rekishi hyōron 歴史評論4 (1991), pp. 13-38.

Ruoff, Kenneth J. Japan’s Imperial House in the Postwar Era, 1945–2019. Harvard East Asian Monographs, 2020.

Sakura Tachibana Kyōkai ed. 桜橘協会編. Sokui tairei kinenchō 即位大礼記念帳. Sakura Tachibana Kyōkai, 1915.

Sekine Masanao. 関根正直 Sokui rei daijōsai taiten kōwa. 即位礼大嘗祭大典講話. Tōkyō Hōbunkan, 1915.

Shii Kazuo 志位和夫. Tennō no seido to Nihon kyōsantō no tachiba 天皇の制度と日本共産党の立場. Nihon Kyōsantō Chūō Iinkai Shuppankyoku, 2019.

Tairei Kiroku Hensan Iinkai ed. 大礼記録編纂委員会. Tairei Kiroku 大礼記録. Shimizu Shoten, 1919.

Takagi Hiroshi 高木博志. “Sokuishiki (rei), Daijōsai” 即位式(礼)・大嘗祭. In Hara Takeshi 原武史 and Yoshida Yutaka 吉田裕 eds. Iwanami Tennō kōshitsu jiten 岩波天皇皇室辞典. Iwanami Shoten, 2005.

Tokoro Isao 所功. Kindai tairei kankei no kihon shiryō shūsei. 近代大礼関係の基本史料集成. Kokusho Kankōkai, 2018.

Notes

I have presented versions of this paper at four venues: Dōshisha University in Kyoto, Monash University in Melbourne, International Christian University in Tokyo, and Tōhoku University in Sendai. I would like thank the organizers, Professors Michael Wachutka, Alison Tokita, Mark Williams and Orion Klautau respectively, for inviting me to address them, their colleagues and students.

The address can be replayed on the Kunaichō 宮内庁 website, where the Japanese and English transcriptions can also be found.

The Japanese text and English translation of the emperor’s address on this occasion can be accessed on the Kunaichō website.

For examples, see Ruoff 2020, pp. 335-339. Ruoff 2020 is a must-read on the post war imperial institution.

This is a two-scene act. Scene 1 was styled “Kenjitō shōkei no gi” 剣璽等承継の儀, and Scene 2 “Sokuigo chōken no gi” 即位後朝見の儀.

Rice and millet used in the Yukiden were harvested in Tochigi Prefecture 栃木県; Kyoto 京都府 provided rice and millet for the Sukiden.

The budget in question is referred to as kyūteihi 宮廷費 in Japanese. It covers “necessary expenditure for the public activities of the imperial house.” There is a second budget, the naiteihi 内廷費, set aside for the private use of the imperial family.

The 2019 amnesty was limited in scope to 550,000 men and women who had been convicted of minor crimes, fined, and paid their fines more than three years previously. Most were guilty of road traffic offenses, it seems. The 1990 amnesty on the occasion of Akihito’s enthronement benefited 2.5 million people with criminal records.

The produce is referred to as niwazumi no tsukue shiromono 庭積の机代物, which translates inelegantly as “items [for display] on tables in the [Daijōkyū] garden.”

Produce from regions in the west of Japan, marked in blue, were placed before the Sukiden Hall; the produce in purple from the east of Japan was placed before the Yukiden Hall.

See, for example, the article on the BBC website, styled “Naruhito: Japan’s emperor proclaims enthronement in ancient ceremony.”

“Meiji tennō gosokuishiki no zu” 明治天皇御即位式之図 (Source: Sekine Masanao. 関根正直 Sokui rei daijōsai kōwa. 即位礼大嘗祭大典講話. Tōkyō Hōbunkan, 1915.)

For the details of the Meiji enthronement rite, I draw on Kunaishō Rinji Teishitsu Henshūkyoku 宮内省臨時帝室編修局 vol. 1. On the enthronement, see also Takagi 2005.

A change of era name for a new reign was not unheard of in the past, but only in the case of the Enryaku 延暦period (782-806) did the same era name endure throughout the reign of the emperor. There were multiple reasons for changing era names; the vast majority had nothing to do with the emperor.

The so-called Shinto-Buddhist separation – or more correctly “clarification” – edicts stripped all vestiges of Buddhism away from shrines, creating in the process entirely new “Shinto” and “Buddhist” spaces. In its rejection of all things Buddhist, the Meiji enthronement was very much an outcome of these historic edicts. On the edicts, see Breen 2000, pp.230-251.

On Fukuba and his role in the Restoration government, see in English Breen 2000, Chapter 12. Fukuba articulated his ambitions for the enthronement in his Sokuishinshiki shō, dated September 1868, just before the event took place.

Daijōsai 大嘗祭 by Nisei Goseda Hōryū 二世五姓田芳柳 (Source: Kunaichō Kunai Kōbunshokan Shozō 宮内庁宮内公文書館所蔵)

Iwakura Tomomi, Kido Takayoshi, Itō Hirobumi and many other senior leaders were not in attendance. They had left Japan a week earlier on 23 December for an extended tour of the US and Europe as members of the so-called Iwakura mission.

The Daijōe kokuyu is reproduced in Tokoro 2018. On the Meiji daijōsai, see especially Miyachi 1991, Takeda 1996 (Chapters 8 and 9) and Breen and Teeuwen 2010 (Chapter 5).

“Ise daibyō shin’etsu robo Ujibashi tsūgyo” 伊勢大廟親謁鹵簿宇治橋通御 (Source: Tairei Kiroku Hensan Iinkai 1919.)

“Gunkan Kawachi kanjō yori mitaru goshōkan Tsukuba kan” 軍艦河内艦上より見たる御召艦筑波艦 (Source: Sakura Tachibana Kyōkai 1916.)

The exposition, known as the Taiten Kinen Kyōto Hakurankai 大典記念京都博覧会, was staged in Okazaki Park, east of the Kamo River, and ran for eighty days from 1 October to 19 December.

“Seiga o mukaematsuru Kyōto” 聖駕を迎えまつる京都 (Source: Ichida Ofusetto Insatsu Gōshi Kaisha Tōkyō Shiten 1915)

The Imperial Household Law did not allow abdication, so Emperor Taishō remained on the throne till his death.

The latest, and most insightful, study of the postwar transformation of the Japanese monarchy is Ruoff 2020.

For party responses both to the emperor’s message and to the issue of abdication, see, for example, the 9 August 2016 editions of the Asahi shinbun, the Mainichi shinbun and the Yomiuri shinbun. The Communist Party reconciled itself to the existence of the “emperor system” at its Annual Conference in 2004. For the arguments, see Shii 2019.

Mainichi shinbun 10 December 2019. An Asahi shinbun poll conducted in July 2019 found that only 7% of LDP members supported jokei tennō, while three times as many, 23%, supported josei tennō. Asahi shinbun 23 July 2019.