Abstract: This article addresses the return of popular protests in Hong Kong in 2020, after the government’s adoption of emergency measures to address the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong and following calls by the Chinese Communist Party for the government to take a much more repressive stance against protests. The pandemic has also accelerated the downturn in U.S.-China relations. The article reviews the parallel, and at times intersecting, evolution of popular protests and pandemic control measures in Hong Kong. It also outlines the ways in which the 2019 protests were departures from previous protest cycles.

Keywords: Hong Kong, democracy, protests, pandemic, U.S.-China relations, Chinese Communist Party

Source: The Economist November 23, 2019

The downward spiral in U.S.-China relations in the midst of a blame game over the COVID-19 pandemic has revived concerns that the two countries are entering a 21st century version of the Cold War. If this is the case, Hong Kong will likely become a flash point in the conflict. Amidst the pandemic, whose first cases appeared in Hong Kong in January 2020, the government of Hong Kong has embarked on a massive crackdown on the opposition and signaled to would-be protest organizers that demonstrations will be met with brutal police force of the sort witnessed at many of last year’s marches and sit-ins. Meanwhile, the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its representatives in Hong Kong are pressuring the government to re-introduce controversial legislation targeting threats to “national security.”

The U.S. Congress and Trump administration responded to last year’s protests in Hong Kong by passing the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, which provides for sanctions against those deemed to be violating human rights in Hong Kong, and for the possible revocation of Hong Kong’s distinct trading status with the United States (after which Hong Kong would be treated as any other city in China in terms of trade and investment policies). One could expect both of those possibilities to materialize in the coming year as the protests in Hong Kong revive and U.S.-China relations worsen across a number of fronts.

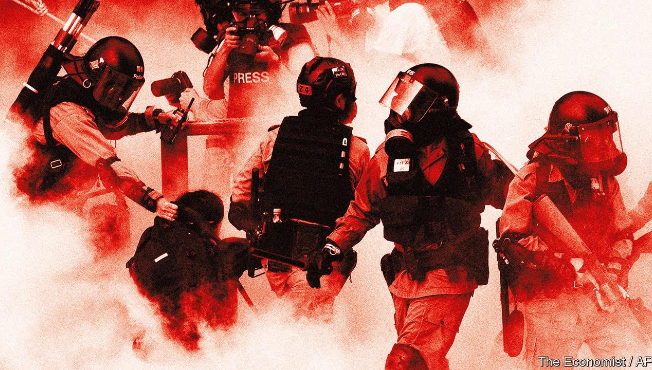

The massive street protests that drew the attention of the world in 2019 may not be repeated in terms of their size and duration, but it’s reasonable to expect large-scale marches and rallies (approved or otherwise) throughout the summer of 2020. Legislative Council elections are to be held in September, raising the possibility of election violence. It’s also reasonable to expect Hong Kong police to continue their use of coercive tactics on crowds of protestors, involving teargas, rubber bullets, or worse. Just recently (May 10-11), riot police set upon peaceful protestors with pepper spray in several malls and other venues, arresting an estimated 200 people—including two student journalists aged 12 and 16.

Many expect a new wave of protests in Hong Kong this summer, but they will take place in global context transformed by the pandemic and the collapsing state of U.S.-China relations. Pandemic control measures by the Hong Kong government can be used to render any protest an illegal act and justify police measures against an “unlawful assembly.” The Hong Kong government, no doubt with Beijing’s support, seems to have calculated that the pandemic presents an opportunity to harass opposition figures and to use brute force against any signs of protestors gathering in the streets and public spaces of the city. The government’s calculation seems to assume that the rest of the world, including the United States, will be sufficiently pre-occupied with managing the COVID-19 crisis to pay much attention to events in Hong Kong. But this calculation ignores the rising levels of Americans’ disaffection with China, a heated presidential campaign in which candidates will criticize each other’s stance on China, and the seeming drift toward a new Cold War. In this context, vivid displays of police brutality against protestors, and the persecution of opposition figures in Hong Kong may draw global attention and compel the United States and other governments to respond with sanctions or other measures.

This essay looks at the intersection of protest and pandemic in Hong Kong, and the dangerous convergence of the crackdown in Hong Kong with a new low in U.S.-China relations.

***

While the Hong Kong government shed its formal colonial status with the transfer of sovereignty from Britain to China in 1997, the government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) is pushing the CCP’s agenda to impose unpopular measures on a citizenry that is increasingly alienated from China, especially among those born just before or after 1997. In mid-April, Luo Huining, Beijing’s newly-appointed Director of the Central Government’s Liaison Office called for the Hong Kong government to pass legislation to identify and sanction those who endanger national security. The draft of such a bill sparked Hong Kong’s first mass protests when it was first introduced in 2003. The occasion on which Luo made his announcement was the Chinese government’s officially designated “National Security Education Day.” Many Hong Kongers, he intoned, “have a weak concept of national security.” National security legislation, Luo said, should be passed by the Hong Kong legislature “as soon as possible.” Carrie Lam, the Hong Kong Chief Executive, added her own remarks on the “holiday” by noting that illegal protests were threats national security (along with hate speech and acts of terrorism). Days later, on April 18, the Hong Kong police arrested 15 members of the opposition, including the elder statesman of the pan-democrats, the 81-year-old Martin Lee. He and others were charged with participating in an illegal protest last year. They await a court hearing on May 18.

The arrests drew international condemnation, from the United Nation’s Human Rights Office, the International Bar Association, and most tellingly, from the Trump White House. Attorney General William Barr called the arrests “an assault on the rule of law” that “demonstrate[d] once again that the Chinese Communist Party cannot be trusted.” Barr’s own assault on the rule of law in the United States, one would suppose, makes him uniquely qualified to recognize it when he sees it. But his statement (along with the response of Secretary of State Mike Pompeo) was clearly part of a new effort to single out the CCP as the source of America’s grievances against China, for its mishandling of the initial outbreak of coronavirus cases in Wuhan, and now for the crackdown on the opposition in Hong Kong. While not inaccurate, these statements do everything to bolster the CCP’s claims that the Hong Kong opposition and protestors are aligned with “hostile foreign forces” (i.e., the American government and NGOs) that aid and abet protests in order to sow instability anywhere they can in China. Pompeo announced on May 6 that the State Department would delay its legally-mandated report to Congress (as required by the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act) assessing the autonomy of Hong Kong from China. The report would presumably be updated to reflect recent developments in Hong Kong.

What Pompeo and others in the U.S. government have failed to grasp is that the situation in Hong Kong is not simply another “pro-democracy” movement. The protests are increasingly resembling a much more complicated movement against a quasi-colonial power. Aspirations for universal suffrage (meaning direct elections of the Chief Executive and a more representative legislature) are indeed an important part of the opposition’s demands. But as in many anti-colonial struggles, the population is divided between those who feel loyalties to and identification with the imperial center—or simply accept the inevitability of the status quo and oppose the actions of the protestors—and those who advocate a separate identity and even the radical stance of independence. Episodes of violence, usually involving police setting on crowds of protestors, fuel further protests as anniversaries are marked and patriotic martyrs are commemorated. Through such linked events, a sustained protest cycle forms that can stretch over years, involving violent conflict, arrests, and convictions.

***

Pandemics and protest first coincided in Hong Kong in 2003, the year that the SARS coronavirus, believed to have originated up the Pearl River in Guangzhou, inflicted a public health crisis on the city from March until June, during which 1,750 cases were recorded and 286 Hong Kong residents died. At the very same time as the SARS pandemic, Beijing pressed the Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa to pass legislation defining threats to national security, in line with Article 23 of the Basic Law. (This is the same measure that Beijing is now insisting that the Hong Kong government pass.) An unprecedented march of 500,000 took place on July 1, 2003 to mark the anniversary of the transfer to PRC sovereignty and to show widespread opposition to the Article 23 legislation. Tung was compelled to withdraw the legislation. After SARS, wearing masks in public became commonplace in Hong Kong, especially during flu seasons. Before SARS, an outbreak of avian influenza (H5N1) in late 1997 (the first case was identified in May) closed schools and compelled the new Hong Kong government to ramp up support for epidemiological research and public health infrastructure. A subsequent epidemic of swine-derived flu (H1N1) in 2009 elicited what experts viewed as a positive public health response, as the Hong Kong government had invested heavily in research, testing, and containment capacities.

In the decade that followed SARS, the Hong Kong government was also deepening its linkages with the mainland through the “Closer Economic Partnership Agreement” (CEPA), which was signed on June 29, 2003, just days before the July 1 protest march. CEPA gave Hong Kong companies and traders preferential access to the PRC markets. At the same time, it set the stage for a rapid expansion in tourism that would eventually see 51 million annual PRC visitors to the city of 7.4 million residents.

As several Hong Kong-based scholars have chronicled, this deepening of trade, tourism, and migration from the PRC gave rise to a “localist” movement. The label (using the difficult to translate “bentu”) had been applied in different contexts before 1997, but as Sebastian Veg has shown, activists and academics revived the term in connection with local heritage protection movements in 2006, when protests occurred to oppose the demolition of the Star Ferry and Queen’s Piers. Localist discourse was not explicitly anti-colonial in the sense of calling for independence, but promoted awareness of Hong Kong’s indigenous history and culture, as distinct from that of the PRC. Localist movements organized numerous mobilizations in the 2010s—all of which can be connected to the 2019 protests. Among these were a 2009-10 campaign to block the demolition of a New Territories village that was in the path of the Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong express railway. The protest failed to block the railway and the residents were forcibly relocated, but it signaled the unease among the Hong Kong public with the deepening sense of integration with the mainland. When the Legislative Council (LegCo) session to approve the financing of the railway was held, an estimated 10,000 protestors held a sit-in outside the LegCo Building. Some of them broke into the LegCo, where police used pepper spray to clear the area. In 2012, protests again asserted the distinctiveness of Hong Kong identity when a movement, led by the 16-year old Joshua Wong, formed to oppose measures by the Hong Kong government to introduce “moral and national education” (meaning a PRC version of Chinese history) into the school curriculum. Demonstrators staged a large rally and sit-in at the Civic Plaza outside LegCo Building. The protests succeeded and the government withdrew the curricular reforms.

The localist sentiment was also prominent during the Umbrella Movement in 2014. Also known by its original moniker of Occupy Central with Love and Peace (OCLP), the protests began in response to Beijing’s announcement that year for a revised electoral system that still denied citizens the means to directly elect the Chief Executive. But it was also described by one of its founders Benny Tai as a “localist democracy movement.” The reference was again to a local culture and identity that was distinct from mainland China in terms of political culture in addition to language, history, and much else. Student protestors launched a class boycott, and in late September occupied Civic Square. They were set on by police using pepper spray, and their use of umbrellas to shield themselves from teargas and pepper spray gave the movement its name. The movement, which occurred over a 79-day period in three locations in the city, came to an end in December, largely through attrition and a government strategy to let the occupied spaces provoke disapproval and even counter-mobilization of citizens who opposed the disruptions to mobility and their livelihoods.

The aftermath of the Umbrella Movement saw a widespread crackdown by Beijing and the Hong Kong government and at the same time, intensified localist sentiment. The opposition or pan-democrats divided along several dimensions, but the most basic were generational and political—with the younger activists eschewing the parties and electoral strategies of the older democrats in favor of direct action, and a third camp that was more explicitly localist, including some candidates and parties competing for legislative seats who overtly called for Hong Kong independence. (The Hong Kong government outlawed these parties and even prohibited elected representatives from taking seats in the legislature in 2016.) At the same time, Beijing launched a sweeping “counter-mobilization” – pushing for the arrests of the leaders of the OCLP campaign, the student leaders in the Umbrella Movement, and much else. Perhaps overly confident in the wake of these measures, Carrie Lam decided to use a murder case that happened in Taiwan involving a Hong Kong resident to introduce the extradition bill in early 2019.

Amidst the 2016-18 crackdown, Hong Kong’s healthcare sector drew accolades for its world-leading standards. Hong Kong’s healthcare system, based on the British National Health Service model, offers free high-quality health care, even if it leads to extended wait times for patients and longer working hours for doctors and hospital staff. Hong Kong was ranked number one in the 2018 Bloomberg’s Healthcare Efficiency Index, a measure that takes into account life expectancy, average healthcare costs per capita, as well as health spending as a share of GDP. (The United States was near the bottom of the list of 56 middle and high-income economies). But the 100,000 medical workers in Hong Kong’s first-rate public hospitals would soon find themselves in the middle of street battles between protestors and police—and by November 2019 would treat an estimated 2,100 wounded protestors, even as Hong Kong police sought to interrogate and arrest suspects inside public hospitals.

What became the city’s largest protest movement began with marches against the extradition bill in April. On the weekend before the bill’s first reading in the LegCo, a march that drew one million took place on June 9. As the bill moved to its second reading a few days later, on June 12, protestors massed outside the LegCo, where police attempted to break them up using a reported 150 rounds of teargas, in quantities that exceeded the 87 rounds used during the full stretch of the 2014 Umbrella Movement. In response to the blatantly repressive tactics by the Hong Kong police, an estimated 1.5 to 2 million people took part in marches on June 16–the largest in the city’s history.

But the large marches and concentrations of demonstrators in prominent civic spaces, a repertoire derived from 2014 and before, soon gave way to the unprecedented tactics of roaming “flash protests” in symbolically important venues such as shopping malls associated with mainland Chinese corporations, transportation hubs that linked with the mainland, and so forth. What was also apparent by mid-summer 2019 was that the protests were led by no formal group or spokespersons, and in this sense leaderless. Social media apps could be used to quickly mobilize large numbers of protestors, and provide participants with a range of information on the whereabouts of police, sympathetic shopkeepers, and medical volunteers. They were, an example of what recent social movement scholars have termed “connective action” based on information sharing across networks rather than the conventional forms of “collective action” involving hierarchical organizations deploying resources to mobilize participants.

What was also distinctive about the 2019 protests—and related to the facility with which social media apps were used—was the age of the participants. A recently published study by Francis L. F. Lee and colleagues confirms what many reports noted anecdotally last year. According to surveys of 12,231 respondents at 19 venues between June 9 and late August, 61 percent were under age 29—but the more compelling observation was that those under age 19 accounted for 11.8 percent of the protestors. (Another 22 percent were ages 20 to 24).

As the protests stretched across the summer, including dramatic scenes of thugs attacking metro passengers, protestors occupying the Hong Kong airport, and a general strike that shut down public transportation, the Hong Kong government responded by drawing on the legacies of its colonial predecessor. Following a series of violent episodes during an October 1 protest (China’s National Day), Carrie Lam announced that the wearing of masks in public would be banned—this was to better identify protestors and arrest them using surveillance techniques. To justify what seemed a violation of civil liberties, she invoked the Emergency Regulations Ordinance, which the colony’s British governor drew up in order to force an end to the crippling 1922 Seaman’s Strike. (A South China Morning Post columnist noted last year that the governor at the time, Reginald Stubbs, showed more competence than Carrie Lam does now because after ending the strike, he brought both sides to the negotiating table, which resulted in workers’ gaining substantial wage increases.) On October 5, the day after the mask ban went into effect, riot police could be seen setting upon those wearing masks in public places. The ban was challenged in court, but was upheld by the Court of Final Appeal in April of 2020, with the stipulation that police could arrest anyone wearing a mask at an “unlawful assembly.”

By then, the mask ban had been rendered irrelevant by the massive citizen response to the government’s bungled attempts to cope with the spread of the coronavirus. Carrie Lam was in Davos at the World Economic Forum when the first cases emerged in Hong Kong, and she was slow to act when she finally did return, postponing calls to close the border with China and even declining to wear a mask—which her civil servants also abjured at first. And yet despite these delays, Hong Kong with its high-density residences and neighborhoods had suffered only 1,039 COVID-19 infections and four deaths by early May 2020. Hong Kongers have attributed the successful outcome not to anything that the Hong Kong government did to protect them, but largely to the actions of the medical community and civil society organizations. In February, medical workers launched a strike to demand the distribution of masks free to the public and the closing of borders with China. The Hong Kong authorities soon complied with both demands. As COVID-19 hot spots such as New York City struggled with mask and personal protective equipment supplies in March, in Hong Kong there were teams of volunteers venturing to every corner of the city to ensure that all residents had masks and related protections.

As the summer approaches with its anniversaries marking recent and past dates of large-scale protests and rallies on June 4, June 9, June 12, June 16, July 1, and others, the Hong Kong government will very likely invoke the Emergency Regulations Ordinance not only to uphold the mask ban but also to prohibit any large gathering. In March 2020, during a brief uptick in new COVID-19 cases, Lam announced a ban on gatherings of more than four people. When the cases were brought under control by early May, she announced an extension of the ban to late May—permitting gatherings of eight. As the protest anniversaries approach in June, it is all but assured that the Hong Kong government will turn down protest permit applications. Undeterred, protestors (very likely wearing masks) will hold marches and rallies on the streets and in symbolically important venues. Invariably, the Hong Kong police will be sent in to arrest the protestors. Even a minor act of violence by the latter, such as property damage to shopfronts, will be framed as evidence for why Hong Kong needs the national security law to punish those who threaten public order: those regarded as a “political virus,” in the words used on May 6 by the CCP official in charge of Hong Kong affairs.

***

The chances for some compromise over electoral reforms, investigations into police conduct during the protests, and amnesty for those arrested for taking part in “illegal” protests now appear, in the midst of the Hong Kong government’s crackdown, even more remote than last year. While some western observers worry about a military intervention that replays scenes of Beijing on June 4, 1989, it’s clear that a different form of intervention is already under way. The CCP has outsourced repression to the Hong Kong government and its own police and security forces. But this repressive move, in the context of U.S.-China tensions, is not without costs for Beijing. Miscalculations over Hong Kong could bring on some version of a “Berlin crisis” in a new Cold War—not with walls and airlifts but with an unending cycle of suppression and corresponding sanctions.