Abstract

A comment by the female star of the Disney film Mulan, supporting Hong Kong police crackdown on democratic protests has led to a massive boycott of the film in Hong Kong.

An upcoming film about a filial daughter who fights against the odds to make it in a man’s world is now fighting against the odds to avoid falling victim to a massive boycott because the star had the temerity to express her point of view. This was an unpopular point of view, at least in Hong Kong, where calls for a boycott of Mulan ring the loudest. Conversely, that criticism immediately gained some two million “likes” on the Chinese mainland, where only half the story of the Hong Kong protests is being told.

The box office stakes are high on both sides of the Hong Kong-mainland divide, and Disney, which has high hopes for Mulan in the Asia market and globally, will have to artfully thread the needle eye of public opinion as it prepares for the release of the live action film in March. Now that publicity for the film has been unwittingly hitched to partisan politics, it will require an extraordinary effort to maintain support on both sides of the Shenzhen River that divides the former British colony from the Chinese mainland.

It started when Mulan star and lead actor, Liu Yifei, made a flippant comment on a social post last summer, stating her support for the Hong Kong police in the early days of the Hong Kong-China conflict. The reaction on social networks was fast and unforgiving; the entire film, representing years of work and millions of dollars investment was suddenly stigmatized by a single remark. Specifically, it put the film at risk of bombing in Hong Kong, a geographically small, but in this case at least, an economically and culturally significant film market.

The controversy arose at a time when Hong Kong airport was besieged by angry protesters against Chinese policy to impose a new extradition law in Hong Kong. A reporter named Fu Guohao, in Hong Kong at the behest of the Chinese state-run Global Times, was forced to undergo a humiliating interrogation and taunting by protesters at the airport who felt the police were hostile to their protest. Fu was ganged-up on by a youthful, quick-fisted mob that suspected him of affiliation with the Hong Kong police, based on the shirt he was wearing. The beleaguered mainlander cried out, “I support the Hong Kong police. You can beat me up now.”

The video, shared widely on television and the internet, showed Fu Guohao being showered with abuse. It looked to be a set-up, at least in the way he played to the camera, but he took some hard knocks and the video went viral.

The Chinese-American star “Crystal” Liu Yifei, who played Mulan in the film, added her voice to the kerfuffle, as did millions of others, posting her reaction to the incident online. What’s more, she made her comment in reaction to the provocative video on a People’s Daily-linked site.

“I, too, support the Hong Kong police. You can all attack me now.”

And attack they did. Liu has been a photogenic lightning rod of anger for Hong Kong protesters ever since, racking up hateful posts on the internet for one hundred days running with no end in sight.

The gentle-looking Liu Yifei, perhaps still feeling a bit in character as a woman warrior after playing Mulan, shared her indignation about the injustice of the August 18, 2019 mob action against the Global Times reporter with the English words, “What a shame for Hong Kong!”

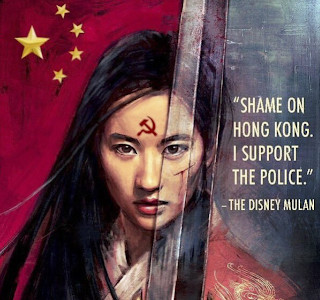

A perfectly reasonable thing to say, to the ear of a native English speaker at least, but it was misconstrued by her detractors, willfully or otherwise, as an admonishment. “Shame on Hong Kong?” How dare she!More angry comments followed and the “shame” meme was widely shared.

The much-awaited trailer for the lavish, live action epic came out on December 5, a half year into the smoke and fire of protesters and police fighting in the streets. Tempers provoked by Liu Yifei’s comment are roiling anew, and the #BoycottMulan hashtag is again exploding with vitriol.

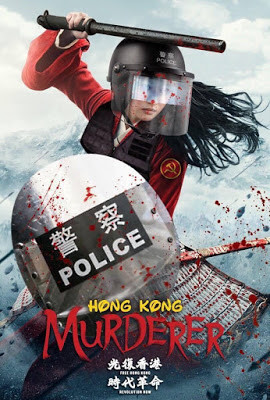

Twitter indignation mobs, reactivated and aroused by the release of the trailer, have resumed their ragtag campaign to denigrate the actress, the movie and even the legendary Mulan. The publicity stills for Mulan have been repurposed by activist artists in ways that are at least as creative as they are mean-spirited.

Mulan is here transformed into Hong Kong Murderer. Instead of seeing Mulan’s reflection in the gleaming sword, as in the publicity shots, one sees the ghostly face of Xi Jinping lurking in the background. Instead of being shown as a heroine and model for young women, warrior Mulan, is transformed into a riot cop with bloodstained armor. In one version, a hammer and sickle is etched on her forehead with the five stars of the Chinese flag as backdrop.

And then there’s the slightly more pleasant guise, in which the benign cartoon Mulan is repurposed as a supporter of the Hong Kong protesters, holding a yellow umbrella instead of a sword.

This is hardly an auspicious start for a long-anticipated blockbuster that is banking on market demand for a China product with a strong female lead. If there’s an upside to the downside, Hong Kong denizens who deign to watch the film will probably be rooting for Mulan’s nemesis to triumph. This is because China’s best-known actress, Gong Li, plays a key role in the film as a “bad” shapeshifting witch. To date, the iconic older star has been spared vitriolic commentary in keeping with her own prudent silence.

Surely Disney would have preferred business as usual. Tweets in support of the HK protests recently got the NBA in hot water with the Chinese government, and now, with an ironic twist, a tweet against the protests has got Disney in trouble—not with communist party-ruled China but capitalist Hong Kong.

It is hard to view the clip of Fu Guohao’s staged humiliation without some sympathy as he’s tied up, smacked and humiliated by angry youth in a way that evokes the Red Guard excesses of the Cultural Revolution. Fortunately, Fu was not seriously hurt. He went on to instant TV fame in the mainland where the media quickly picked up on the incident, unlike scenes of police abuse which never

get an airing there.

But the footage was real enough, and just one of many clips of mindless, graphic violence engaged in by both protesters and police. It might be observed that a Rashomon effect is in play, especially with video taken out of context. How the action portrayed is interpreted depends in part on the political leanings of the viewer.

Liu Yifei, took the bait, so to speak. She fell for the crying narrative arc of the clip in question. Which is not to say that what was shown in the video was not true, only to say that, in isolation, it provides insufficient data to make a sweeping pronouncement in favor of either protesters or police.

The protests in Hong Kong, already reckoned to be the most live-streamed political event in history, may be one for the record books for producing viral political tweets, memes and manipulative imagery. But Mulan won’t be coming to the rescue any time soon, not as long as some viewers regard her as part of the problem.