Abstract: On October 31, 2019, a massive fire tore through the UNESCO World Heritage site of Shuri Castle in Okinawa, sparking a global reaction and comparisons with another World Heritage site. As in the case of Notre Dame, government officials immedicately declared their intention to rebuild, and donations flooded in from Okinawa, throughout Japan, and other countries. Shuri Castle is widely recognized as the symbol of the former Ryukyu kingdom. This article shows that the significance of Shuri Castle can only be fully understood by examining it in the context of castles in modern Japan. By understanding the commonalities and differences between Shuri Castle and mainland castles, we use the site as a tool to examine Okinawa’s modern history. In spite of Shuri Castle’s early origins and architecture differing somewhat from mainland Japanese castles, it was treated similarly to these other sites in the modern period. Like hundreds of other castles, Shuri Castle was taken over by the central government in the early Meiji period (1868-1912). Like dozens of other castles, Shuri Castle eventually became a garrison for the modern military. Like the castles at Nagoya, Hiroshima, Wakayama, Okayama, Ogaki, and Fukuyama, it was destroyed by US bombs in 1945. Like many other castles, it was demilitarized under the US Occupation and came to host cultural and educational facilities. The reconstruction of Shuri Castle from wood using traditional techniques in 1992 echoed similar projects at Kanazawa, Kakegawa, and Ōzu, as well as dozens of planned reconstructions. For many regions in Japan, castles have played a similar role to Shuri Castle, serving at times as symbols of connection to the nation, and at times as symbols of a local identity opposed to the often oppressive power of the central state. Examining the modern history of Shuri Castle as a Japanese castle can further complicate our understandings of the complex dynamics of Okinawa’s relationship with Japan over the past 150 years.

On October 31, 2019, a massive fire tore through the UNESCO World Heritage site of Shuri Castle in Okinawa, sparking a global reaction and comparisons with the recent fire at Notre Dame, another World Heritage site. As in the case of Notre Dame, government officials immediately declared their intention to rebuild, and donations flooded in from throughout Japan and other countries. The scale of the response to Shuri Castle is also a reflection of the position of castles as some of Japan’s most popular and important heritage sites. This could recently be seen in the case of the Kumamoto Earthquake of 2016, a major disaster which killed at least fifty people and injured thousands more. Amidst the extensive destruction and loss of life, it was drone footage of the damaged towers of the Kumamoto Castle keep (tenshu) and walls that was shown by major news agencies around the world. The castle, which had long been an important site of local pride and identity, quickly became the symbol of both the earthquake and subsequent efforts by Kumamoto residents to rebuild and recover.

In the case of the Shuri fire, although there were no casualties, the disturbance caused by the fire and commotion would have been especially distressing for many residents given the devastating wartime experiences that destroyed the castle in 1945, compounded by the ongoing militarization of the island by the United States. After the initial shock of the fire, many concerns relate to the lack of skilled artisans for the reconstruction and the economic impact on tourism, as millions of people visit the castle each year. The significance of Shuri Castle to many is reflected in the surge of public donations to reconstruct the site, which reached 1.2 billion Yen during the first month after the fire. An important element of discussion is the symbolic importance of the site and its relationship to broader controversies in Okinawa today. International headlines lamented the loss of the “500-year old world heritage site” and “600-year-old Shuri Castle complex,” but coverage also mentioned that the castle had been extensively rebuilt in 1992 before being designated a World Heritage site in 2000.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The focus of media coverage has generally been on the role of Shuri Castle as the symbol of the former Ryukyu Kingdom, which conquered and ruled various parts of the Ryukyu Islands, from about the late fifteenth century. It was at this time that the castle was given its present Chinese-influenced design, as part of King Shō Shin’s (1465-1527) centralization of power. The castle had looked quite different before burning to the ground in the 1450s during a civil war among the Shō family.1 Coverage has stressed the importance of Shuri Castle for many Okinawans, who have long been victims of discrimination as well as violence by both the Japanese state and the US military, which stations roughly half of its 54,000 Japan-based troops in Okinawa, even though the islands are only 1% of Japan’s land area. In contrast, local narratives have sought to promote a narrative of Okinawan and Ryukyuan culture as traditionally peaceful and outward looking.

Shuri Castle’s important role in the turbulent modern history of Okinawa has left many unresolved historical issues and contemporary controversies. The castle was a central site of the devastating Battle of Okinawa in early summer 1945, when tens of thousands of Okinawan civilians were killed in the fighting including some who died as a result of “compulsory mass suicides” directed by the Imperial Japanese Army. The IJA had turned the castle into its headquarters, with countless tunnels and caves, and the site was almost entirely destroyed in the battle. After Japan’s surrender in 1945, Okinawa remained under US control until 1971, serving as an important base for both the Korean War and Vietnam War. When Okinawa reverted to its former status as a Japanese prefecture, the US military retained and subsequently expanded the heavy presence that continues to cause considerable resentment.

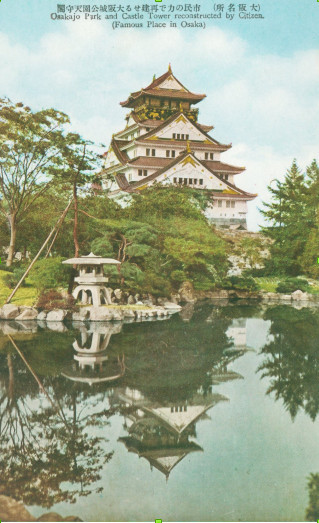

Shuri Castle is an eloquent witness to the larger histories of the Ryukyu Kingdom and subsequently Okinawa Prefecture, which are in many ways unique within Japan. The castle has significant architectural differences from mainland Japanese castles, which developed into their final form in the late sixteenth century, and are usually marked by deep moats, angled stone walls, and towering wooden keeps at their centers. Their very large scale reflects the power and wealth of their builders, as well as the intensity of the warfare that swept across all of Japan at the time. In contrast, Shuri Castle’s large central hall, curving curtain walls, and dry moats are some of its prominent unique elements, and its scale is closer to that of some of Japan’s smaller regional castles. Tze May Loo has recently highlighted the centrality of Shuri Castle to debates on heritage in Okinawa, arguing that Shuri is a critical site for understanding the development of the islands’ complex relationship with mainland Japan.2 Certainly, many people have made the case that Okinawa became Japan’s first colony, and that its residents suffered greatly under domination by Satsuma, Japan, and the United States. On the other hand, the theme of resistance is insufficient to explain Okinawa’s modern history. Many Okinawans desired acceptance as Japanese in the imperial period, especially, and sought to take advantage of benefits as citizens of a major empire, including through migration to mainland Japan and overseas.3

Photo courtesy of Greg Smits.

In the debates surrounding Okinawa’s relationship with more powerful states, Shuri Castle has often been held up as a symbol of Ryukyuan or Okinawan identity, with its history of being occupied, neglected, sacrificed, destroyed, and recovered reflecting the fate of the islands’ inhabitants. While this narrative is enticing and Shuri Castle can tell us a great deal about larger historical processes, such an approach can also be problematic insofar as it considers Shuri in isolation from other castles in mainland Japan. Many of the dynamics surrounding Shuri Castle are representative of developments in other castle sites and reflect broader policies toward Japanese castles and heritage, and were not limited to Okinawa.

We argue that the significance of Shuri Castle can only be fully understood by examining it in the context of castles in modern Japan. By understanding the commonalities and differences Shuri Castle has with mainland castles, we can more effectively use the site as a tool to examine Okinawa’s modern history. In this study, we look at Shuri Castle relative to other castles in Japan, providing points of departure for further research on Shuri and other sites as witnesses of modern history. In spite of Shuri’s early origins and architecture differing somewhat from mainland Japanese castles, it was treated similarly to these other sites in the modern period. Like hundreds of other castles, Shuri was taken over by the central government in the early Meiji period (1868-1912). Like dozens of other castles, Shuri eventually became a garrison for the modern military. Like the castles at Nagoya, Hiroshima, Wakayama, Okayama, Ogaki, and Fukuyama, it was destroyed by US bombs in 1945. Like many other castles, it was demilitarized under the US Occupation and came to host cultural and educational facilities. The reconstruction of Shuri Castle from wood using traditional techniques in 1992 echoed similar projects at Kanazawa, Kakegawa, and Ōzu, as well as dozens of planned reconstructions. 1992 also saw the designation of Himeji Castle as one of Japan’s first two UNESCO World Heritage sites, eight years before Shuri received that designation. For many regions in Japan, castles have played a similar role to Shuri, serving at times as symbols of connection to the nation, and at times as symbols of a local identity opposed to the often oppressive power of the central state. Examining the modern history of Shuri Castle as a Japanese castle can further complicate our understandings of the complex dynamics of Okinawa’s relationship with Japan over the past 150 years.

Shuri Castle as a castle in imperial Japan

One of the fundamental issues surrounding Shuri Castle is its very status as a castle, with various groups arguing that it was either a fortification or a palace, or both. The Chinese character typically translated as “castle” (城, shiro, jō) had a range of meanings throughout its history, and could refer to cities, castles, and even the Great Wall of China. In the narratives that stress the peaceful heritage of the Ryukyu Kingdom, Shuri is primarily a palace that hosted diplomatic exchanges with China, Japan, and other states in the premodern period. This message is epitomized by the Shureimon – the Gate of Courtesy that was originally built in 1579, reconstructed after the Second World War, and is featured on the 2000-Yen note.4 Shuri Palace certainly fulfilled all of these roles. In a different reading, however, Shuri Castle was a site of Shuri’s power and authority over the surrounding islands. Starting in the mid fifteenth century under King Shō Taikyū (r. 1454-1460) and culminating in King Shō Shin’s (r. 1477-1526) wars of conquest, Shuri became the center of what one historian has called a “Ryukyu empire,” created and held in place by military force.5 In 1609, this empire was subjugated by the Japanese domain of Satsuma, which controlled Ryukyu from that point until the late nineteenth century.6

The status of Shuri as a castle and/or palace raises an important question for other castles in Japan, which also served as both fortifications and residences of regional rulers. As in the case of Shuri, the military and peaceful functions of Japanese castles have been stressed at different times in the modern period, in line with local and national agendas. In this sense, reading Shuri as a castle, just as one would approach Japanese castles, provides a useful comparison. Soon after the Meiji Restoration, in 1871, the new government undertook a major administrative reform in which it “abolished domains and established prefectures” (haihan chiken), greatly reducing the number of organizational units in the country. As part of this reform, the regional ruling families “returned” their castles to the emperor and were obliged to move permanently to the new imperial capital of Tokyo to reduce the danger of military challenges to the new state. Governors were appointed to the newly created prefectures, and many castles were converted into administrative centers, while others were taken over by the growing imperial army. In this sense, the forced relocation of the Ryukyuan King Shō Tai (1843-1901) to Tokyo in 1879 to become a marquis, and the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture the same year under a centrally appointed governor, were very much in line with practice throughout Japan.7

It is important to note that although castles were large and valuable urban spaces in the early Meiji period, they were also viewed largely as useless and even embarrassing reminders of the recent “feudal” past, and potential obstacles to modernization. Militarily, castles had been obsolete for centuries, and their upkeep was a major drain on domain budgets during the Edo period (1603-1868). Daimyo across Japan had long desired to tear their castles down, and dozens of requests for permission to do so flooded into Tokyo from the domains in the first years of the Meiji period.8 Hundreds of castle structures were torn down or removed in the 1870s. This was motivated to a considerable degree by the economic difficulties of the local administrations who now had to pay for castle maintenance, as well as the financial troubles of the former samurai class, whose stipends were reduced and finally eliminated. Obsolete castle buildings were often sold off for scrap to raise money for former samurai, who in some regions were also allowed to use moats and other spaces for agriculture.9

Edo Castle, the former home of the Tokugawa shoguns and the largest castle in Japan, suffered a similar fate. It was already in a significant state of decay in the 1860s, even if the bloodless surrender of the castle to the imperial loyalist armies in 1868 prevented further damage. It was decided in the early 1870s to tear the castle down, and there is little existing evidence of many of the original buildings at the time. Photographs taken by various foreigners in the 1860s and 1870s are important resources.10 Foreigners were typically more intrigued by Japanese castles than were Japanese in the 1870s, and many photographs from the time were taken or commissioned by foreigners.11 Edo Castle was also the site of an unusual event, when the art specialist Ninagawa Noritane (1835-82) obtained permission to photograph the castle in 1871 shortly before it was demolished. Ninagawa had close ties to foreigners and was highly aware of developing heritage and display practices in the West. Judith Vitale further places Ninagawa’s project within larger discourses on the Romantic appreciation of ruins that was highly influential at the time.12

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

See online version of Ninagawa’s book.

Accounts by foreigners provide some of the most revealing insights regarding attitudes towards castles in the early Meiji period. The German diplomat Max von Brandt was involved in the decision to save the keep of Nagoya Castle, which was slated for demolition in the early 1870s.13 Christopher Dresser recalled conflicts between civilian and military authorities over control of Nagoya Castle when he visited in 1876.14 The traveler Francis Guillemard (1852-1933) took the only surviving photographs of the Takamatsu Castle keep before it was destroyed in 1884. These were only recently rediscovered in Cambridge University Library and have been vital to an ongoing movement to rebuild the castle.15

On his journey aboard the Marchesa in the early 1880s, Guillemard also visited Okinawa and Shuri Castle, and provided a detailed account. According to Guillemard, the castle was highly restricted, and he describes being “conducted to the fortress, whither none of the crowd who had hitherto surrounded us were permitted to follow.”16 Guillemard was impressed by the “vast area that is included within the fortifications,” organized within “three distinct lines of fortifications, with ample space between them for the maneuvering of any number of troops.” Like Japanese castles, this was certainly a military site, if an obsolete one: “In the present day of large ordnance, these wonderful defences would, of course, be reduced with the greatest of ease, but, in the old days of bow and arrow and hand-to-hand fighting they might just have been considered impregnable.”17 As he moved towards the center of the castle, he discovered “barracks, or rather what serve as such at the present time, for we discovered that about two hundred Japanese soldiers were stationed there. In the large courtyard surrounded by these buildings we came across a small squad of them drilling.”18 He finally reached the palace at the very center of the castle, the first Western visitor to do so: “A more dismal sight could hardly have been imagined. We wandered through room after room, through corridors, reception-halls, women’s apartments, through the servants’ quarters, through a perfect labyrinth of buildings, which were in a state of indescribable dilapidation. The place could not have been inhabited for years. Every article of ornament had been removed. … In all directions the woodwork had been torn away for firewood, and an occasional ray of light from above showed that the roof was in no better condition than the rest of the building.”19

Guillemard, a keen observer, hinted at tensions between the Japanese rulers and the local populace. “I had a great desire to get at further particulars of the state of the island under its new rulers and tried our new friend (a Japanese officer) and Uyeno (Guillemard’s guide) upon the subject, but in vain. The latter, who, if he chose, could be intelligent enough, suddenly became hopelessly stupid, and after a few reiterated questions à travers, I gave up the task in despair.”20 Similarly, when they came across the soldiers drilling, “Uyeno was evidently rather disturbed at this incident, being apparently desirous that we should remain in ignorance of the fact that the castle was now occupied by Japanese troops.”21 Guillemard’s experience seems to imply a difference from the Japanese mainland, where the army very openly occupied and controlled castle spaces, although there were tensions between castle garrisons and civilian populations everywhere in Japan.

We should be hesitant to presume that the state of the castle is evidence of Japanese discrimination against Okinawans, or that neglect of the castle by the Japanese military and other bodies was part of a desire to assimilate Okinawa and erase Ryukyuan culture. Nor should we assume that Japanese policies towards Shuri Castle were driven by concern that it could prove a rallying point for anti-Japanese feeling at the time. While these larger trends certainly existed, the state of castles in mainland Japan was no different. Both military and civilian castles were in advanced states of decay in the 1880s, and there was little effort to preserve either in most of the country. Furthermore, policy towards castles does not generally seem to have varied between domains that had been loyal to the Tokugawa shogunate and those that supported the victorious imperial loyalist armies. For example, the keeps of both Hagi Castle and Aizu-Wakamatsu Castle were torn down largely for practical reasons in 1874, but these actions were only ascribed political motivations many decades later.22

Similarly, the occupation of Shuri Castle by the military reflected practice throughout Japan, where disused castle sites were taken over by the newly-formed Imperial Japanese Army in the early Meiji period. The first six regional army commands were all located in castles, as were almost all of the first 24 infantry regiments created in the years leading up to the Sino-Japanese War in 1894.23 Many of these vast urban spaces that had been restricted spaces of power and authority in the early modern period continued to serve this function after 1868, now with modern barracks and parade grounds, and sentry posts in front of medieval gates. As in the case of Shuri—or even Okinawa today—many civilians in Japanese cities experienced the military as vital to the local economy, but also as an oppressive and disruptive force. Throughout Japan, especially in the Taisho period (1912-1926), civil society groups sought in vain to remove the army from urban castle garrisons to suburban sites where the problems associated with the presence of thousands of young soldiers would be less immediately felt.24

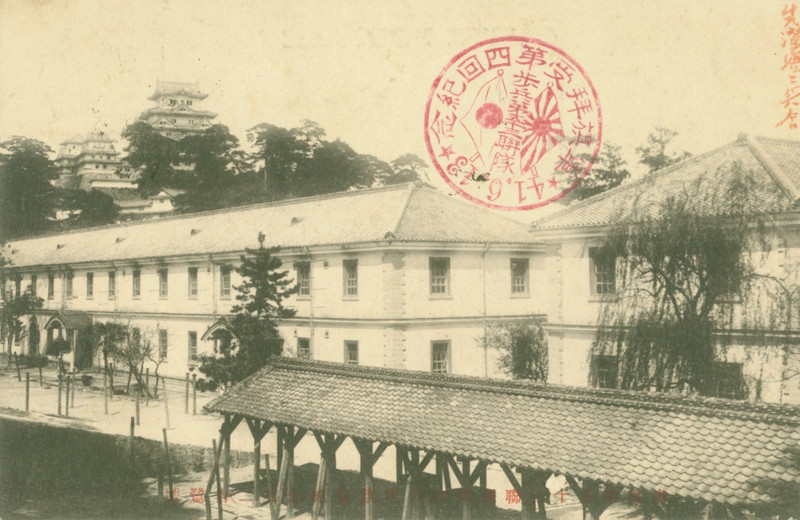

The general neglect of many mainland castles lasted well into the twentieth century. As the writer Tokutomi Roka (1868-1927) described the dilapidated keep at Matsue Castle in 1916, “it seemed as though a feudal ghost might appear.”25 The keep of Echizen Maruoka Castle was also used as a makeshift shrine, with pillars removed for the altar and a large window cut in to let in more light.26 Across Japan, both military and civilian administrators did not hesitate to tear down walls and other structures, fill moats for roads and railway lines, and sell off parts of castles for other uses, including the building of schools and administrative buildings, agriculture and sports, and even horse racing and cycle tracks.27 Similarly, the great hall of Shuri Castle was used as a barracks by the army until 1896, when the Okinawa Normal School took over the center of the site and used the main hall as a dormitory.28

It was only in the early twentieth century that castles began to be appreciated by the public throughout the country on a broader scale for their aesthetic and heritage value. Military castles were opened to the citizenry on the occasion of annual regimental festivals, which were major events on the social calendar. Natsume Sōseki recounts the celebratory atmosphere during such a festival in Matsuyama in his 1906 novel Botchan.29 These events became especially popular after the Sino-Japanese (1894-95) and Russo-Japanese (1904-05) wars, as commemoration of the war dead took place in “soul-gathering shrines” (shōkonsha), often located on parade grounds or in civilian castle parks.30 Castles were also popular sites for industrial exhibitions, both on military parade grounds and in civilian parks. At the Fifth National Industrial Exhibition in Osaka in 1903, the Aichi Prefecture Pavilion was built in the shape of a castle, reflecting Nagoya’s status as having the largest surviving keep in Japan.31 This pattern continued into the postwar, as Aichi and Nagoya pavilions were often built as imitation castles. Castles were also used as airfields and to demonstrate the new aviation technology, drawing very large crowds in cities including Nagoya and Osaka.32

Courtesy of the National Diet Library.

The first decade of the twentieth century also saw the first attempts to reconstruct lost keeps within castles. The keep at Kōfu Castle was temporarily reconstructed on the occasion of an exhibition in 1906, adorned with bright electric lights in a marriage of traditional architecture and modern technology.33 In 1910, the Gifu Society for the Preservation of Beautiful Scenery (hoshōkai) undertook a more permanent reconstruction of its lost castle keep, using materials from a disused rail bridge that was being replaced.34 This project is significant not only because it was the first lasting reconstruction, but also because it was undertaken by a civil society group interested in heritage preservation. These groups became increasingly widespread and active in the Taisho period (1912-1926), and had an important role in promoting the appreciation of castle heritage and preservation.35 In the case of Shuri Castle, although efforts did not extend as far as reconstruction, the first years of the twentieth century also saw the first movements by local authorities toward obtaining ownership of the castle for public use as a museum, park, and historical site, echoing similar developments elsewhere.36

The growth of preservation groups was closely related to the development of heritage legislation in modern Japan. The Old Shrines and Temples Preservation Act was passed in 1897, but did not cover secular structures such as castles. It was only with the passage of the National Treasures Preservation Law in 1929 that castles were given heritage protection and funding.37 Although no castle keeps were torn down in the early twentieth century, they only began to be formally protected using national legislation in the 1930s. Some, such as Nagoya and Odawara, enjoyed a modicum of protection during a period when they served as Imperial Detached Palaces, but even the imperial household was prone to making significant alterations to castle sites.38 In this context, the case of Shuri Castle is an interesting departure from practice regarding castles on the Japanese mainland. The site was judged to have reached too severe a state of decay to merit repair by the early 1920s, and the military made plans to pull the palace down. This decision was reflected in similar moves at other castles in Japan, and should not be seen as ideological or restricted to Okinawa. At this point, the architect Itō Chūta intervened to preserve the historic buildings. While he was based in the Japanese mainland, Itō had traveled extensively and published studies of Ryukyuan architecture. Itō also knew that castles everywhere remained under threat, especially in regions like Shuri with limited financial resources to invest in heritage protection.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Itō’s strategy to save Shuri Castle was a clever ploy that made use of existing heritage legislation. As this did not cover castles, but did cover shrines, it was decided to designate the palace as Okinawa Shrine, thereby making it eligible for public support and protection. The establishment of shrines within castles was widespread throughout Japan at the time. Former ruling families often established shrines to their ancestors in their castles in the Meiji period, thereby creating new sites of worship as alternatives to existing Buddhist temples, which often represented a considerable financial burden.39 Shrines were also established in castles to celebrate national heroes, while dozens of civilian and military castles contained shōkonsha shrines to worship the war dead. These shrines, which were affiliated with the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, were converted to “nation-protecting shrines” (gokoku jinja) in 1939 to deal with the increasing number of war dead. There was roughly one gokoku jinja per prefecture, with others found in imperial possessions overseas. Even today, dozens of castles contain gokoku jinja that are reminders of the role of castles in the imperial past.

Photo by the authors, 2018.

In this context, although the designation of the Shuri palace as a shrine was unique as an approach to heritage legislation, it was not at all unusual in terms of the links between religion and castles throughout Japan at the time. The designation as a shrine was certainly driven by mainland Japanese, but this was primarily in order to save the site as part of a movement that was also led by mainlanders. In this way, Shuri was the first castle in Japan to receive official protection, five years before Nagoya Castle became the first site covered under new legislation passed in 1929. Furthermore, as Gregory Smits has shown, the notion of a uniform Okinawan identity around the turn of the twentieth century was a reaction to mainland efforts to incorporate the islands into its expanding empire. Smits notes that Okinawans “simultaneously became both Ryukyuan and Japanese.”40 Being Japanese was a growing part of Okinawan identity, and many accepted the incorporation into Japan, seeking a greater role in the empire.41 Seen through this prism, the acceptance of the Okinawa Shrine was not unusual.

Castles in wartime Japan

The early Showa period (1926-1989) saw a variety of trends related to castles in Japan, and Shuri was no exception. One important development was the academic study of castles in tandem with greater public interest. The reconstruction of the Osaka Castle keep from steel-reinforced concrete in 1928-31 revealed a shortage of specialist knowledge on castle construction, and also inspired a boom in academic and popular engagement. Graduate students in architectural history, especially, began to examine castles, and the most influential scholars and architects of the early postwar were trained in the 1930s and 1940s, some supported by the Imperial Japanese Army.42 Here again, Shuri Castle was a forerunner, having been studied by Itō in the early 1920s, whereas dedicated studies of castles in mainland Japan only began to appear at the end of that decade.43 In 1931, the center of Osaka Castle was opened as a public park, and the imperial household gave Nagoya Castle keep to the municipality for the same purpose (and to avoid the financial burden of major repairs). The change in heritage legislation in 1929 to include more recent structures meant that castles qualified for the first time, with the keep at Nagoya designated the first National Treasure. Himeji, Sendai, Okayama, Fukuyama, and Hiroshima followed in 1931, and Shuri Castle was formally designated a National Treasure in its own right as a castle, rather than as a shrine, in 1933. By 1935, sixteen castles throughout Japan had been designated National Treasures.44

Castles benefited from increasing pride in, and mobilization of, Japan’s martial history and heritage in the service of the nation and empire. The military made increasing symbolic and practical use of castles in the early Showa period, especially during the Fifteen Year War with China (1931-1945). Castles increasingly featured in military propaganda and were celebrated as physical manifestations of the “way of the samurai” (bushidō), while the soldiers that occupied castle garrisons were seen as the spiritual heirs of Japan’s heavily idealized ancient warriors. The Kwantung Army Headquarters in Xinjing, Manchuria, was built to resemble the castles that the army occupied back home. In Japan, both military and civilian castles held major National Defense Exhibitions and public military maneuvers, while the increasing number of war dead were commemorated at the gokoku shrines. Also, in the 1930s, as Justin Aukema has argued, Shuri Castle became a point of convergence for the assimilation of Okinawans into the Japanese Empire, both as a physical symbol of their ancient “Japaneseness” and as a site for inculcating the imperial ideology into high school students.45

Hsin-Ching (Xinjing)” (late 1930s).

Postcard in the authors’ collection.

In the early 1940s, military castles focused on their role as garrisons, and many castles were again restricted. In Osaka, the windows of the castle keep were covered over in 1940 to block views of the military garrison and arsenal, and the keep was closed to the public entirely in 1942.46 As military sites, castles had been involved in all of Japan’s modern wars, but never more so than during the Pacific War. US bombing destroyed six original castle keeps, including the civilian castles at Wakayama, Fukuyama, Ogaki, and Okayama, as well as the large watchtower at Mito. Castle keeps in military garrisons were also destroyed, including at Nagoya and Hiroshima. The latter was blown over by the shockwave from the atomic bomb, which completely destroyed the military command and Hiroshima Gokoku Shrine that shared the main bailey of the castle. The concrete keep at Osaka was damaged by bombs but survived largely intact. The keep of Himeji Castle had been covered by camouflage netting to hide it from American bombers, although its survival was arguably less due to this precautionary measure than to the US military’s policy of targeting working-class residential areas in bombing raids of 1945. In Himeji, the greatest destruction was in the bombing of the mixed residential and industrial zone in the East of the city.47

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

As in Japanese castles, the fate of Shuri Castle was closely linked to that of the military that occupied it. However, the situation at Shuri also differed in very significant ways, as it was the only castle to see actual combat rather than aerial bombing alone. Students were enlisted by the Japanese 32nd Army to dig a maze of tunnels underneath the castle for a new military headquarters.48 By transforming the castle into an explicit military site that housed many commanding officers, the army made Shuri a target that the US army was especially keen to take.49 The Battle of Okinawa in April-June 1945 was one of the most violent and tragic episodes of the war, especially with regard to the civilian population. One particularly controversial aspects is what has come to be known as a policy of “compulsory mass suicide,” Japanese soldiers encouraged Okinawan civilians hiding in caves and bunkers to kill themselves using grenades and other methods rather than surrender. They also killed countless civilians to prevent them from using up food and other resources, or to ensure that the official image that the Japanese people would choose death over surrender was maintained. The killing of Okinawans both around Shuri Castle and elsewhere on the islands were among the greatest tragedies of the war, with some estimating that civilian casualties may have numbered 160,000. While the vast majority of civilians in Okinawa and elsewhere were killed by US bombing and shelling, this was exacerbated by the Japanese army’s generally dismissive view of civilians. This was also the case on the Japanese mainland, with arsenal workers in Osaka and elsewhere, including many women and children, forced to work through bombing raids, resulting in massive casualties. In Okinawa, this disdain for the civilian population was exacerbated by linguistic and cultural differences that led to far more violent treatment of the local population by the military.

“Liberation” and Occupation

From the first moments of its postwar history Shuri Castle was already a controversial site. According to Eugene Sledge, a US marine who participated in the Battle of Okinawa, the first flag that was planted over the ruins of Shuri Castle was not the US but the Confederate flag. Sledge recalled, “in the morning [of May 29, 1945] . . . Marines had attacked eastward into the ruins of Shuri Castle and had raised the Confederate flag. When we learned that the flag of the Confederacy had been hoisted over the very heart and soul of Japanese resistance, all of us Southerners cheered loudly. The Yankees among us grumbled.”50 The flag was later replaced with the US flag that flew over Guadalcanal, “a fitting tribute to the men of the 1st Marine Division who had been first into the Japanese Citadel.”51 The incident is still a topic of controversy in the US.52 For Okinawans, however, it mattered little what flag the foreign occupiers raised over the pile of rubble that was once Shuri Castle. US artillery had reduced the castle to what American reporters described as a “crater-of-the-moon landscape.”53 The physical destruction extended beyond the buildings to the natural environment. As Senge Tetsuma recalled, “the entire edifice and the surrounding forests were destroyed in the flames of the recent Great War and in vain the only thing you see are stone hedges and withered broken trees.”54 The human cost was incalculable with almost a quarter of Okinawa’s prewar population perishing at the hands of both the US army and their Japanese “defenders.”

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons (link)

The fall of the castle, “the very heart and soul of Japanese resistance,” was a significant symbolic victory for the Americans, and the site continued to play a significant role in the reconstruction of the island under US occupation. Shortly after the US takeover, the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands (USCAR) decided to raze the ruins of the castle and build in its place a new “University of the Ryukyus.” The university was established under the guidance of Michigan State University. As Mire Koikari writes, “the establishment of [the University of the Ryukyus] in 1951 [was] another example of Cold War cultural strategies, [which] mobilized higher education as a central vehicle of the dissemination of US values, culture, education, and technology.”55 Such strategies were deployed throughout the developing world, with land grant universities playing a leading role in disseminating a vision of American modernity and democracy as the apex of postwar reconstruction. US reports “depicted local Okinawans as happily hauling away rubble as U.S. bulldozers leveled the castle site,” portraying Okinawans as willing participants in the project.56 As Justin Aukema argues, the building of the university was construed as “a symbolic victory of U.S.-led modernity over the ancient forces of feudalism and militarism, a condition that [Brigadier General John Hinds] compared to liberation from bondage.”57

At least initially, this liberation entailed an erasure of both military and Ryukyuan structures on the site. The intellectual work done in the university would be the continuation of the idea of liberation. As Hinds wrote in his address at the opening ceremony of the University of the Ryukyus, “The bulldozers were able to clear the debris from the location, but they could not scrape away three generations of moral and intellectual subjugation…. The Ryukyuans have raised a monument to this ideal [of freedom] in the very building of the University by their own hands, standing as it does on a war-devastated eminence once dominated by a 14th century feudal castle.”58 Americans sought to create a new Okinawan identity free from the decades of Japanese oppression, but this did not mean a wholesale “return” to pre-Japanese annexation traditions. USCAR did not rebuild Shuri Castle, but built a university in its place. Americans and their liberal allies lumped together the castle’s military garrison and their Ryukyuan predecessors as agents of “feudal” subjugation. American-style education was intended to free Okinawans from feudal habits. In January 1955, USCAR Governor General Lyman Lemnitzer wrote, “Less than one hundred years ago, it was upon this site that the leaders and rulers of Okinawa were born and educated for responsibilities of leadership. These were, however, children born of a privileged class and in number few.”59 In contrast, the university students were portrayed as representing a new kind of Okinawa: democratic, free, and equal. Lemnitzer specifically stated that he was against reconstructing the castle, as “he hoped that the feudalism for which it stood was ‘forever dead.’” As Aukema points out, Lemnitzer also referred to the university as a “new national shrine,” thereby symbolically replacing the Okinawa Shrine, and further conflating the feudal and militarist eras.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The move to replace military barracks with study halls was not unique to Shuri Castle. The Americans certainly played a more direct role in this symbolic transformation in Okinawa, but at least seven other Japanese cities transformed their former military castles into universities during or immediately after the occupation, and schools were built in many other castle sites. This was not the case in former garrisons outside of castles. Many Imperial Japanese Army and Navy bases became permanent US bases or, later, Japanese Self Defense Forces (JSDF) bases. As Fukubayashi Tōru argues, the conversion from “military city” into a more “peace-oriented identity . . . was never an issue in places like [the port cities of] Kure, Yokosuka, and Sasebo, where city life still revolves around the military.”60 In castle towns, however, the association with the military and samurai class was an important part of local identity, and the transformation was important for their “reinvention” in the postwar. As Imamura Yōichi points out, “the conversion of former military grounds into universities was endowed, for such castle towns, with much symbolism.”61

For instance, the trajectory of Kanazawa Castle is almost identical to Shuri’s, with the site converted first into a university and then back into a castle, built with original materials and local craftsmanship, and becoming the anchor of a revived local culture. Kanazawa’s official history prides itself on the transition from “gunto into gakuto (military town to university town), which symbolized the transformation of the city,” and the “building of a university in the castle as a symbol of the construction of a nation of peace and culture.”62 As in many other sites, the US 6th army initially took over from the Imperial Japanese Army and set up camp in the existing barracks. The 6th army, however, quickly relocated and the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers designated the site for the building of a university. However, the castle site became entangled in struggles between the city, which sought to build a public university, and a Jōdo Shinshū Buddhist group that desired to build a religious university in the castle.

The Buddhists wished to commemorate the 450th anniversary of the building of a temple by Shōnin Rennyō (1415–1499), the eighth head priest of the Honganji order, on the castle site. The temple was destroyed by the armies of the warlord Oda Nobunaga’s (1534-82), and the Buddhists presented the building of a Buddhist university as a renunciation of feudalism and an expression of their supposed centuries-old hostility to militarism. Kanazawa City, which was ultimately successful in its university project at the expense of the Buddhists, also used the language of peace and presented Kanazawa as first and foremost a university town. A December 1947 petition invoked “Kanazawa’s ‘tradition of higher learning,’ its 300 years as a castle town, a baronial seat of power and a seat of learning, its medical schools and other universities.” These factors made Kanazawa “an ideal space for [supporting] education befitting of the construction of a cultural nation and the newly reborn Japan’s idea of democracy.”63

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Unlike the University of the Ryukyus in Shuri, however, Kanazawa University cherished its association with the castle. University brochures described it as the “Castle University,” and “the Birth of the New Kanazawa University,” which transformed the site from the “home of soldiers to the home of students.”64 In Shuri, emphasis was on the erasure of the past, rather than its repossession. In a way, USCAR was too successful in pushing the idea of overcoming feudalism. As USCAR started to encourage a separate Ryukyuan identity as a way to forestall a return of sovereignty to Japan, students in the University of the Ryukyus opposed the restoration of castle buildings. In the 1959 words of one Student Council member, rebuilding the castle would help “separate Okinawa from the homeland (sokoku) [i.e. Japan].” For the student activist, “Shuri castle was a “symbol of feudalism” which represented the “culture of the rulers (shihaisha no bunka),” and, therefore, “considering that Okinawa has not yet fully democratized […] is not a cultural symbol […] that we should be proud of.”65 This hostility to reconstruction echoed contemporary trends in mainland Japan, albeit with a particular Okinawan angle. Left-wing activists fought against reconstruction efforts in Nagoya, Hiroshima, Wakayama, and many other sites. Rebuilding castles was seen as a colossal waste of money at a time when many Japanese were still struggling to obtain proper housing. In Wakayama, socialist MP Nakatani Tetsuya opposed the mayor’s reconstruction plans with the slogan “bread or nostalgia.”

Nakatani further connected the building of Wakayama Castle in 1958 to the return of feudalism and militarism. In Wakayama, and elsewhere, as Japan was rocked by conflicts over the US-Japan Security Treaty (ANPO), local resistance to castle projects was entangled with a struggle over interpretations of the local past. If local elites saw rebuilding their destroyed castles as symbolizing the end of the postwar and the revival of their towns, the left almost uniformly saw this as the revival of an elite culture that should be categorically opposed. Historian Okamoto Ryōichi captured this sentiment in 1969, writing, “The recent castle building planners’ hackneyed slogan that a castle…is the pride of [our] hometown, or a symbol of yearning, never tells [us] historical facts in an accurate way. Rather, castles and their keeps were [built] from blood and tears. Looking up at that sky-piercing [cruel] tower, our ancestors, the common people, could not help feeling coercion and indignation.”66 In Okinawa, as well, tourism groups and cultural circles pushed for reconstruction against local resistance. Seen in this light, debates in Okinawa were part of a wider struggle over history, where elites tried to turn aristocratic culture into popular traditions and symbols of popular pride, countering earlier views of the characteristics as “feudal.”

Reconstructing history and heritage

Such anti-castle rhetoric increasingly became a minority opinion in Okinawa and elsewhere as political maneuvers over the reversion of the islands to Japan brought back the prospect of the restoration of the castle with the support of the Japanese government. As reversion became a reality, two views of Okinawan heritage, and the castle’s place in it, emerged. Supporters of integration with Japan, along with prominent mainland cultural figures, advocated rebuilding the castle as a Japanese cultural property. The National Diet and other bodies allocated funds for surveys and later for the reconstruction of the castle, which was eventually built to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the reversion.67 Other groups within Okinawa now blamed the Japanese army for the destruction of the castle, arguing that the castle should symbolize a unique Ryukyuan identity, separate from and in opposition to Japan.68

In 1970, the Okinawan Bunkazai Hogo Iinkai (Committee for the Protection of Cultural Properties) appealed for government funds to restore the castle, while at the same time positioning it as a monument to peaceful co-existence, “The Seiden [main hall] of Shuri Castle,” argued the committee, “is a monument to the era of great commerce that our ancestors actively engaged in five to six hundred years ago throughout Southeast Asia.”69 The castle, a former military site and garrison of both the Ryukyuan kings and the Japanese state, was now recast as a center of commerce. This characterization developed during the restoration campaign into a powerful narrative of a peaceful Ryukyu victimized by its various conquerors, from Satsuma to Japan to the US military. As Teruya Seisho, one of the main promoters of the restoration campaign, wrote, “Shuri Castle [was] as unique among castles in Japan and the world. The old castles on the mainland and abroad were…marked by tall, fortified castle towers that evidence their function as manifestations of power and military might while our Ryukyu promptly forbade the carrying of swords and issued peace proclamations before others in the world. In other words, banning weapons, we established benevolence and virtue as national policy.”70

As Gerald Figal argues, this “myth of being a weaponless state” increasingly became a central tenet of Okinawan identity, while Gregory Smits writes of the “myth of Ryukyuan pacifism.”71 Okinawans undoubtedly were and still are victims of history and the greater powers around them. Nevertheless, the revision of Ryukyuan history was problematic in that it erased Shuri’s difficult relationship with other islands, and obscured the diversity of the region’s cultures and history as they developed through intense connections with Kyushu, Korea and the East Asian maritime world.72 In addition, the trajectory of Shuri Castle was not as unique as Teruya claimed. Both its past history and modern recreation were paralleled in mainland castles, many of which did not possess “tall fortified towers” or have any practical military function for centuries. Even the trope of victimization by Tokyo was an echo of castle restoration campaigns in Aizu-Wakamatsu, Shimabara, and other marginalized regions. In Aizu-Wakamatsu, a contentious castle restoration campaign used the memory of Aizu’s defeat at the hands of the imperial armies in 1868. As local historian Tanaka Matsuo wrote in 1958, “Aizu has known defeat and sorrow from the eighth century on . . . All Japanese experienced the bitter taste of defeat in the last World War, however, [in Aizu] many are [still] harboring resentment from the time of the civil war. Aizu’s Tsuruga Castle is the focus of [such feelings].” Aizu native Hoshi Ryōichi echoed this, writing that the Satsuma and Chōshū “massacres of 3,000 people outside Aizu Castle became the model for Japan’s invasion of Asia.”73

Image courtesy of the National Diet Library.

The trajectory of conflict and contradiction, which characterized mainland castles as well as Shuri, continued into the physical reconstruction of the castle. For many Okinawans, the reconstruction of the castle and its recognition by UNESCO were sources of great pride in their heritage. At the same time, this process erased much of the more difficult history of Shuri Castle and Okinawa as a whole. As elsewhere in Japan, the desire to erase the modern military past and recover pre-imperial heritage was strong in Okinawa, and in the 1980s it was agreed to move Ryukyu University to another site and to rebuild the original Shuri Castle using traditional techniques and materials. The focus at Shuri Castle was placed squarely on its older Ryukyuan heritage before the turmoil of the modern period. The castle was built under the slogan, “Okinawa’s postwar will not end unless Shuri Castle is rebuilt.”74 Castles throughout Japan were built using versions of this slogan. The rebuilding was intended to restore stability and recover the feelings of furusato (hometown) that was lost in the destructive wave of modern warfare and urbanization. In Hiroshima, Nagoya, Wakayama, as well as at Shuri, the reconstruction of the castle was presented as the recovery of a lost past. Samurai parades, Shinto dedication ceremonies, and castle festivals with local dances and enthusiastic popular celebrations were aimed at showing that castle reconstructions were expressions of the popular will. In Nagoya, pro-castle campaigners connected the loss of the castle keep with “the loss of stability during the postwar confusion. [Therefore] popular sentiment demanded the rebuilding of the symbol of our hometown.”75 Shuri Castle’s reconstruction in 1989 followed this well-trodden path as the groundbreaking ceremony (kikōshiki) was accompanied by the Kunigami Lumber-Carrying Ceremony Festival, in which timber from local villages was carried down the Naha main street, joined by local performers, folk dances, and cries of “this is the lumber of the heavenly lord of Shuri.”

In Shuri, such festivals were seen by some as manipulation by local elites and the Japanese government of popular feelings of local pride. Furthermore, the coupling of the reconstruction with the reversion anniversary was controversial. Like the student activists before them, anti-base and local activists broke with the prefecture over what they saw as an overemphasis on tourism development. For many Okinawans, carrying “lumber for heavenly the lords of the castle” evoked little pride. In echoes of Wakayama, several groups demanded investment in the welfare of Okinawans rather than in the castle. A local resident remarked in an interview, “The national and prefectural government have been reconstructing Shurijyo (sic.), an ancient castle in Okinawa, but the move has nothing to do with our common lives…the image of Okinawa should be one that reflects the realities of everyday life, not a superficial one that is imposed, like the castle.”76 Similarly, local activists from Shuri itself formed the Association of Residents Concerned over the Shuri Castle Park Project (Shurijō Kōen Jigyō ni Kakaru Jūmin no Kai) that vehemently opposed the rebuilding. The group astutely used war imagery and Okinawa and Hiroshima’s victimization in portraying the reconstruction as an elite project that ignored local grievances, “suggesting that while Shuri Castle was destroyed in the war, its rebuilding now will destroy the daily life of people in the area.”77

By tying the site’s military past to its own struggle against tourism-driven development, the association pointed out that the restoration of the castle was also an act of erasure. As left wing assembly members in Okinawa noted, the neglect of the command bunkers underneath the castle meant that the prefecture was literally burying the castle’s painful history underneath its restored splendor.78 The Shuri reconstruction was completed in 1992, the same year that Japan’s most famous castle, Himeji Castle, became one of the nation’s first two UNESCO World Heritage sites. Himeji Castle had also served as a major military base until 1945, and this legacy has also been largely erased as the public history of the site focuses almost entirely on the pre-modern period. Another former military base, Hiroshima Castle, has similarly removed most traces of the modern military, and its focal point is a 1950s concrete reconstruction of the keep that was destroyed by the atomic bomb. Similar concrete keeps are now being torn down in favor of “authentic” wooden structures. This is a further act of erasure, this time of the postwar castle boom.

Conclusions

The issues of authenticity discussed in the case of Notre Dame are also important in the case of Japanese castles, but they are compounded by the fraught modern history of these very prominent sites. The great keep of Nagoya Castle, the largest in Japan until its destruction by US bombs, was rebuilt out of concrete in the late 1950s, and that structure is now being demolished to make way for an “authentic” wooden reconstruction to be completed by 2022 at a cost of more than 500 million US dollars. At the same time, its modern history has been largely erased, as Nagoya Castle also served as a major garrison until 1945. The same is true of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, which was the central site of the imperial succession ceremonies that marked the beginning of the Reiwa Period in May 2019.86 The legacy of the site as the Imperial Castle and garrison of the Imperial Guard through the Second World War is largely obscured. Osaka Castle, another former military base, refurbished its popular concrete keep in the late 1990s, and Prime Minister Abe Shinzo was roundly criticized for mocking the presence of elevators in the castle during the G20 Summit in June 2019. This controversy reflected tensions between authenticity and accessibility that are also erupting in Nagoya.

shortly before being closed for reconstruction from wood.

Photo by the authors.

The recent burning of Shuri Castle not only sparked reminders of Notre Dame, but also brought memories of images of the wartime destruction of Nagoya Castle and other important heritage sites. The cycles of destruction and reconstruction of Shuri Castle should be seen in the context of broader developments concerning castles in modern Japan. As we discuss in our recent book, Japan’s Castles: Citadels of Modernity in War and Peace, castles in many regions in Japan have served as both symbols of connection to the nation, as well as symbols of a local identity opposed to the oppressive and even violent power of Tokyo. Shuri Castle also reflects these dynamics. As attention turns towards the reconstruction of the structures that were lost in October 2019, old and new controversies over the site may well come to the fore. Concerns over authenticity may be sidelined by larger debates concerning the humanitarian, political, and symbolic issues surrounding Shuri Castle’s turbulent and tragic modern history.

The authors thank Gerald Figal, Mark Selden, Gregory Smits, and Victoria Young for their detailed comments and suggestions on this article.

Notes

1 Smits, Gregory. Maritime Ryukyu, 1050-1650. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2018. pp. 93-4, 113, 161-4, 189-92.

2 Loo, Tze May. Heritage Politics: Shuri Castle and Okinawa’s Incorporation into Modern Japan, 1879-2000. Lexington Books, 2014. pp. 12-13.

3 Smits, Gregory. “New Cultures, New Identities: Becoming Okinawan and Japanese in Nineteenth-Century Ryukyu,” in Peter Nosco, James Ketelaar, and Yasunori Kokima eds. Values, Identity, and Equality in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Japan. Leiden: Brill, 2015. pp. 159-180; Smits, Gregory. Visions of Ryukyu: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1999. pp. 149-155.

4 For a discussion of the complex politics surrounding the original construction of the gate, see: Smits, Maritime Ryukyu, p. 211.

5 Smits, Maritime Ryukyu, pp. 161-192.

6 Smits, Visions of Ryukyu, p. 146.

7 Ibid. p. 146.

8 Benesch, Oleg and Ran Zwigenberg. Japan’s Castles: Citadels of Modernity in War and Peace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019. pp. 29-30.

9 Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, p. 30.

10 Vitale, Judith. “The destruction and rediscovery of Edo Castle: ‘picturesque ruins’, ‘war ruins’,” Japan Forum, 31:4 (2019).

11 Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, p. 53.

12 Vitale, “The destruction and rediscovery of Edo Castle.”

13 Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, p. 50

14 Dresser, Christopher. Japan: Its Architecture, Art, and Art Manufactures. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1882. p. 181.

15 Koyama Noboru. Kenburijji Daigaku hizō Meiji koshashin: Mākēzā Gō no Nihon ryokō. Tokyo: Heibonsha, 2005.

16 Guillemard, Francis Henry Hill. The cruise of the Marchesa to Kamschatka & New Guinea. London : J. Murray, 1889. p. 42.

17 Ibid. pp. 42-43.

18 Ibid. p. 43.

19 Ibid. pp. 43-44.

20 Ibid. p. 44.

21 Ibid. p. 43.

22 Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, pp. 36-39, 161.

23 Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, p. 100.

24 Benesch, Oleg. “Castles and the Militarisation of Urban Society in Imperial Japan,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 28 (Dec. 2018), pp. 107-134.

25 NHK Matsue Hōsōkyoku ed. Shimane no hyakunen. Matsue: NHK Matsue Hōsōkyoku, 1968.

26 Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, p. 94.

27 Ibid. pp. 117, 173, 175, 279.

28 Aukema, Justin. “Cultures of (Dis)remembrance: War Memories at Shuri Castle,” Gendai Shakai Kenkyūka Ronshū (Contemporary Society Bulletin) Kyōto Joshi Daigaku, 13 (March, 2019), p. 72.

29 Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, pp. 118-119.

30 Ibid. p. 116.

31 Ibid. p. 86.

32 Ibid. pp. 115-116.

33 Nonaka Katsutoshi. “Jōshi ni kensetsu sareta kasetsu mogi tenshukaku no kensetsu keii to igi: senzen no chihō toshi ni okeru mogi tenshukaku no kensetsu ni kan suru kenkyū, sono 3,” Nihon kenchiku gakkai keikaku kei ronbun shū, 78:689 (July 2013), pp. 1553–1554.

34 Nonaka Katsutoshi. “Sengoku ki jōkaku no jōshi ni kensetsu sareta mogi tenshukaku no kensetsu keii to igi: senzen no chihō toshi ni okeru mogi tenshukaku no kensetsu ni kan suru kenkyū, sono 1,” Nihon kenchiku gakkai keikaku kei ronbun shū, 75:650 (April 2010), p. 838.

35 Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, pp. 89-92.

36 Loo, Heritage Politics, pp. 45-47

37 Larsen, Knut Einar, ed. Nara Conference on Authenticity: In Relation to the World Heritage Convention. Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 1995. p. 177.

38 Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, p. 55.

39 Lebra, Takie Sugiyama. Above the Clouds: Status Culture of the Modern Japanese Nobility. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1993. pp. 135–141; Japan’s Castles, p. 78.

40 Smits, “New Cultures, New Identities,” pp. 159-180. Smits, Visions of Ryukyu, p. 143

41 Smits, Visions of Ryukyu, pp. 148-151.

42 Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, pp. 148-158.

43 Toya, Nobuhiro. “Kindai ni okeru ‘Ryūkyū kenchiku’ no seiritsu to chiiki shakai,” Nihon kenchiku gakkai keikaku kei ronbun shū, 73:623 (Jan, 2008), pp. 205-212.

44 Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, p. 150.

45 Aukema, “Cultures of (Dis)remembrance,” p. 73.

46 Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, p. 179.

47 Ibid. p. 181.

48 Aukema, “Cultures of (Dis)remembrance,” pp. 73-74.

49 Our thanks to Gerald Figal for pointing this out.

50 Sledge, E. B. With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa. New York: Presidio Press, 2010. P. 300. We thank Chris Nelson for pointing this incident out to us.

51 Ibid.

53 Cited in Aukema, “Cultures of (Dis)remembrance,” pp. 74

54 Figal, Gerald. Beachheads: War, Peace, and Tourism in Postwar Okinawa. Blue Ridge Summit: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012. p. 137.

55 Koikari, Mire. Cold War Encounters in US-occupied Okinawa: Women, Militarized Domesticity, and Transnationalism in East Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. p. 37.

56 Quoted in Aukema, “Cultures of (Dis)remembrance,” p. 74.

57 Aukema, “Cultures of (Dis)remembrance,” pp. 75.

58 Ibid, 75.

59 Ibid, 75.

60 Fukubayashi Tōru. “Gunto Fushimi no keisei to shūen,” in Harada Keiichi ed. Chiiki no naka no guntai 4: koto, shōto no guntai, Kinki. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2015. p.68.

61 Imamura Yōichi, “Sengo Nihon ni okeru kyūgun yōchi no gakkō e no ten’yō to bunkyō shigaichi no keisei,” Toshikeikaku ronbunshū 49:1 (2014), p. 44.

62 Cited in Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, p. 198.

63 Cited in ibid. p. 202.

64 Cited in ibid. p. 207.

65 Aukema, “Cultures of (Dis)remembrance,” p. 78.

66 Cited in Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, p. 319.

67 Aukema, “Cultures of (Dis)remembrance,” p. 80.

68 Figal, Beachheads, p. 144.

69 Figal, Beachheads, p. 140.

70 Cited in Figal, Beachheads, p. 154.

71 Ibid. p. 152; also see this.

72 Smits, Maritime Ryukyu; Smits, Visions of Ryukyu.

73 Cited in Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, pp. 279-280n.

74 Figal, Beachheads, p. 135.

75 Benesch and Zwigenberg, Japan’s Castles, p. 299.

76 Japan Times, May 16, 1992.

77 Figal, Beachheads, p. 148.

78 in Aukema, “Cultures of (Dis)remembrance,” p. 88.