|

Prime Minister Abe Shinzō and Suzuki Muneo in September 2016 (Nikkan Gendai) |

At the start of the 2000s, Suzuki Muneo was one of the most prominent politicians in Japan. Elected to the House of Representatives for the first time in 1983, Suzuki eventually served eight terms. He became a powerful figure in the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and was appointed head of the Hokkaidō and Okinawa Development agencies in 1997. He also became deputy chief cabinet secretary in the government of Obuchi Keizō in 1998. However, while these are senior positions, Suzuki’s real power was unofficial. Exercising extraordinary influence over the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) that often exceeded that of the foreign minister, Suzuki established himself as a key figure in Japanese foreign policy, especially with regard to Russia.

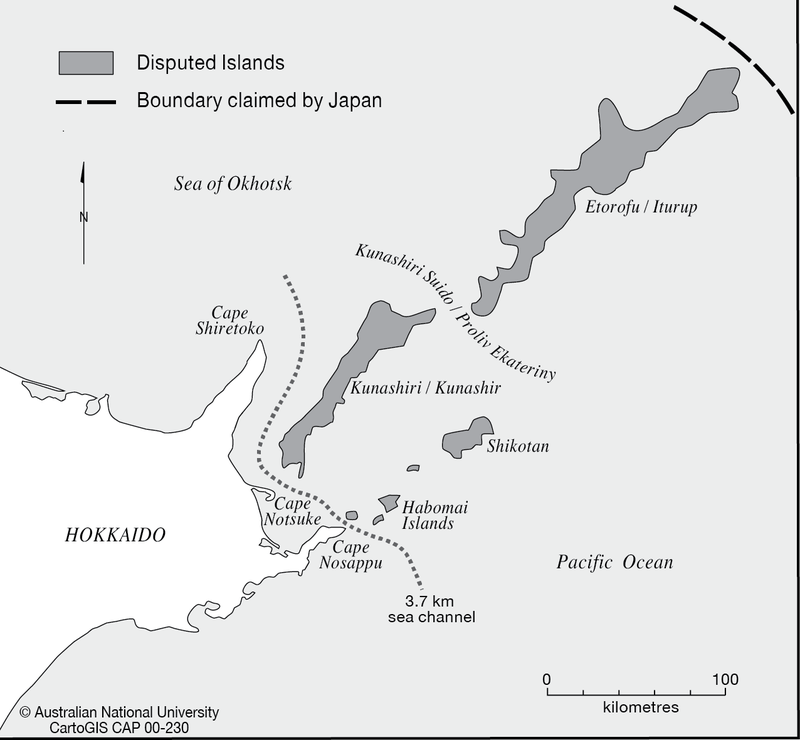

Above all, in advance of the Irkutsk summit between President Vladimir Putin and Prime Minister Mori Yoshirō in March 2001, Suzuki, in close cooperation with certain Japanese diplomats, pioneered what they regarded as a more realistic means of resolving the longstanding dispute over the Russian-held Southern Kuril Islands, which are claimed by Japan as the Northern Territories. Suzuki’s strategy entailed discontinuing Japan’s hitherto insistence on Russia’s simultaneous recognition of Japanese sovereignty over all four of the disputed islands.1 Instead, Suzuki promoted a phased approach that would see the transfer of the two smaller islands of Shikotan and Habomai, followed by continued negotiations over the status of the larger islands of Iturup and Kunashir, which are known as Etorofu and Kunashiri in Japanese. This initiative proved highly controversial since critics, including within MOFA, feared that it effectively meant abandoning Japan’s claim to all four islands. Ultimately, after bitter infighting within Japan’s foreign-policy elite, the policy was rejected in favour of a more conventional four-island approach after Koizumi Jun’ichirō replaced Mori as prime minister in April 2001. Suzuki was therefore left to lament what he saw as a missed opportunity, claiming that “The return of the Northern Territories was before our eyes.” (2012: 197).

|

Map of the disputed islands (CartoGIS, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University) |

Having reached the peak of his power, Suzuki’s fall was precipitous. In February 2002, in a meeting of the Budget Committee of the lower house, Sasaki Kenshō of the Japanese Communist Party accused Suzuki of misusing government funds that had been allocated for the Northern Territories. This marked the start of an escalating series of corruption allegations, which led to Suzuki’s resignation from the LDP in March and his arrest in June. In 2004, after spending 437 days in pretrial detention, Suzuki was found guilty by the Tokyo District Court on two counts of accepting bribes, one count of perjury during testimony before the Budget Committee, and one count of violating the Political Funds Control Law for concealing donations (Carlson and Reed 2018: 71-2). After his appeal was rejected and his conviction upheld by the Supreme Court in 2010, Suzuki was sent to prison for a period of two years, though he was released on parole after 12 months. He was also barred from political office until 2017. Adding to his troubles, Suzuki was diagnosed with cancer in 2003, resulting in the removal of two thirds of his stomach. He was also treated for cancer of the oesophagus in 2010.

Such developments would be expected to terminate any political career, yet Suzuki has proved remarkably resilient and has succeeded in restoring much of his former influence. Most striking is that, since December 2015, Suzuki has met regularly with Prime Minister Abe Shinzō, becoming one of his leading advisors on Japan’s Russia policy (Suzuki 2018: 28-9). In particular, Abe regularly consults with Suzuki ahead of meetings with President Putin. For instance, in advance of Abe’s talks with Putin on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Ōsaka on 29 June 2019, Suzuki met Abe twice, on 5 June and 26 June. Not coincidentally, Abe’s Russia policy has come to bear many of the hallmarks of the approach pioneered by Suzuki during the early 2000s. This includes moving away from the demand that Russia recognise Japan’s right to sovereignty over all four of the disputed islands, and the placement of emphasis instead on conducting joint economic projects on the contested territory. In other words, after a gap of almost 20 years, Suzuki’s policy from 2001, which came to be known as the “two-plus-alpha” formula, is back as the focal point of Japan’s Russia policy.

Furthermore, Suzuki presents himself as an unofficial envoy to Russia. He visited Moscow in April 2019, where he met chairman of the Federation Council’s Committee on International Affairs Konstantin Kosachev. During the visit, Suzuki announced (accurately) that the countries’ “2+2” meeting between the defence and foreign ministers would take place before the end of May, something that the foreign ministries had yet to confirm (Nikkei 2019). Additionally, there are signs that Suzuki is again active behind the scenes. For example, when Diet member Maruyama Hodaka disgraced himself during a visa-free visit to the disputed island of Kunashir in May 2019 by drunkenly raising the prospect of Japan seizing the disputed islands by force, the Russian ambassador Mikhail Galuzin phoned Suzuki to ask how Maruyama’s behaviour should be interpreted (Satō 2019).2 In Suzuki’s own words, “My role is to create an atmosphere in which the prime minister can confidently conduct negotiations. Supporting from behind is fine for me.” (Tanewata 2019).

After his initial conviction, Suzuki formed Shintō Daichi and was re-elected to the lower house as the party’s sole representative in the elections of September 2005. However, despite remaining head of his own party, Suzuki has maintained ties with the LDP. This bond was strengthened when Suzuki’s daughter, Takako, joined the LDP in September 2017 and was elected to the lower house in the October election.3 Despite her brief tenure in the party and her relative youth (she was born in 1986), Suzuki Takako was appointed parliamentary vice minister of defence in October 2018. There is little doubt that this promotion owed much to her father’s close ties with Prime Minister Abe. Moreover, despite supposedly representing different parties, Suzuki Muneo and Takako continued to hold joint events that were attended by LDP grandees. For example, on 1 June 2019 they held a joint fundraising event in Sapporo that was attended by Minister for Economic Revitalisation Motegi Toshimitsu, as well as chair of the LDP’s General Council Katō Katsunobu (Hokkaidō Shinbun 2019b). This is further evidence of Suzuki’s closeness to governing circles.

Not everything, however, has been going in Suzuki’s favour. On 20 March 2019, the Tokyo District Court dismissed his application for a retrial to overturn his criminal conviction and thereby clear his name (Sankei Shinbun 2019a). Additionally, his cancer of the oesophagus returned and he underwent surgery on 27 May. Undeterred by these setbacks, Suzuki ran in the upper-house elections on 21 July as a candidate for Nippon Ishin no Kai, a conservative party based in Ōsaka that is ideologically close to the LDP. Participating in the proportional section of the vote, Suzuki was successfully elected, thereby completing his remarkable journey from prison cell to the floor of the House of Councillors.

It is not unusual for Japanese politicians to bounce back from corruption scandals, yet the scale of Suzuki Muneo’s revival is exceptional. Unlike most other politicians who face allegations of illegal activity, Suzuki was actually sent to prison and banned from public office for five years. Furthermore, at the time of his prosecution, he was widely vilified by the Japanese media in what was described as “Suzuki-bashing” (Togo 2011: 139). Yet, despite this destruction of his public image in the early 2000s, Suzuki has managed, not only to return to national politics, but to regain significant leverage over government policy. He also enjoys a degree of access to the prime minister that is extraordinary for a convicted criminal who is neither a member of the ruling party nor (until July 2019) a member of parliament.

The purpose of this article is to analyse how it has been possible for Suzuki Muneo to first establish, and then reestablish, such political influence. It will also examine his impact on Japan-Russia relations. In so doing, the aim is to gain new insight into this remarkable politician, but also to understand what Suzuki’s case says about Japanese politics more broadly.

The emergence of Suzuki Muneo

Japanese politics has a strong hereditary streak and many politicians owe their initial success to famous political forebears. However, this is not the case with Suzuki Muneo. Suzuki was born in January 1948 in Ashoro, eastern Hokkaidō. As he recounts in one of his many books, his family was not especially poor but nor were they ever really comfortable. Both parents worked long hours on their farm and, as a child, Suzuki himself often had to help out with the livestock and in the fields (Suzuki 2012: 6-7). After completing high school, Suzuki was expected to take an administrative job in a coal mine and had to persuade his parents to support his dream of attending university instead. He was eventually accepted at Takushoku University (a private institution in Tokyo) and Suzuki tells the story of how his father had to sell the family’s best horse to afford the tuition (Suzuki 2012: 106). Tragically, one year later, when Suzuki was 19 years old, his father died of a brain haemorrhage. This deepened the family’s woes and Suzuki was only able to continue his studies thanks to the support of his mother and older brother.

This humble, rural upbringing forms a key part of Suzuki’s political identity.4 He claims that he was interested in politics from an early age and wrote in a junior high-school essay that it was his dream to become a politician. His political beliefs were further developed during a visit to Tokyo in the second year of high school. This school trip took place in 1964, just a month before the start of the Tokyo Olympics. Suzuki explains that he was impressed by the scale of the city, as well as by the number of tall buildings and the quality of the infrastructure. Most of all, he was shocked by the gap in living standards between the capital city and the Hokkaidō countryside. He says that this inspired him to enter politics so that he could work to bridge this divide (Suzuki 2012: 7).

Suzuki therefore presents himself as a man of the people, working to create a fairer society that serves the interests of ordinary citizens, especially those in rural areas. He is also a vocal opponent of neoliberalism, which he claims became influential in Japan as a result of the administration of Prime Minister Koizumi Jun’ichirō (2001-06). Suzuki fears that, due to the pursuit of privatisation and the freeing of market forces, Japan’s national unity and traditional values have been eroded and it has become a society in which “the weak are meat and the strong do eat” (Suzuki 2012: 9-10). Added to this, he is concerned about the lack of social mobility and warns that, if you are born into a poor family, you cannot get the education you need in order to get a good job (Suzuki 2012: 146). To remedy this, Suzuki argues for more government funding for regional revitalisation, including to maintain and develop road and rail networks in Hokkaidō. He also argues for a return to an “old Japan” in which people did more to support their community instead of only being concerned with themselves. To achieve this, he says it is essential for Japanese politicians to set a good moral example (Suzuki 2012: 135).

Lacking a privileged start in life, Suzuki had to work hard to establish himself in national politics. Indeed, Suzuki boasts of the “Suzuki Muneo style”, which is his strategy of working twice as hard as anyone else and emphasising face-to-face engagement with the voters (Suzuki 2012: 154). This approach was on display during the campaign for the July 2019 upper-house election. During just the first three days, Suzuki visited the most easterly, westerly, and northerly points of Japan, and by the end of the campaign he had travelled 21,171 km (Suzuki 2019d). Suzuki is also active on the internet, writing a personal blog since 2013 and not even missing a day when admitted to hospital for cancer treatment in May 2019. This incessant activity is consistent with Suzuki’s personality, which Tōgō Kazuhiko, a former Japanese diplomat who was closely associated with Suzuki at the start of the 2000s, describes as “ne-aka”, meaning innately cheerful or, literally, with a bright root.5

Suzuki’s first job in politics was as secretary to Nakagawa Ichirō, a politician who he continues to lionise as the “Kennedy of eastern Hokkaidō” (Suzuki 2012: 107). Nakagawa was a senior figure in the LDP and served as minister of agriculture from 1977 to 1978. He also stood for election for the presidency of the LDP in 1982 and would have become prime minister had he not lost to Nakasone Yasuhiro. Suzuki describes Nakagawa as a father figure to whom he devoted 13 years of his life (Suzuki 2012: 108). It was when working for Nakagawa that Suzuki demonstrated his capacity for extraordinary hard work, often returning home at one or two o’clock at night and going to collect Nakagawa again at six o’clock in the morning (Katō 2002: 12). It was also at this time that Suzuki began to show an interest in relations with Russia (or the Soviet Union, as it then was). As a politician from Hokkaidō, Nakagawa naturally wished to improve relations with Japan’s northern neighbour. What is more, Nakagawa’s ministerial portfolio included fisheries, which was a prominent area of bilateral cooperation following the signing of a Soviet-Japan fisheries agreement in 1977. Suzuki therefore came to share Nakagawa’s interest in this relationship and, ultimately, the aim of strengthening ties with Russia became his defining “personal passion”.6

|

Nakagawa Ichirō and Suzuki Muneo |

Even at this early stage in his political career, Suzuki was a divisive figure. In particular, Nakagawa’s wife Sadako is said to have been strongly against Suzuki’s appointment as secretary, believing that there was something untrustworthy in Suzuki’s constant restlessness (Katō 2002: 11). Critics also claim that, during his time in Nakagawa’s office, Suzuki became increasingly imperious. Hiranuma Takeo, who was also a secretary to Nakagawa, is quoted as saying that, if he allowed the phone to ring even once before answering, Suzuki would hit him in the head (Katō 2002: 13). It is also reported that Suzuki even felt bold enough to harangue members of parliament visiting Nakagawa’s office (Katō 2002: 13). Ultimately, Suzuki’s influence was such that, even if Nakagawa authorised something, it would not happen until Suzuki approved it too (Katō 2002: 13).

The source of this power is said to have been Suzuki’s control over Nakagawa’s finances. Katō Akira, who has written an excoriating book about Suzuki, describes him as an extremely effective political fundraiser (Katō 2002: 14). This made Suzuki valuable to Nakagawa. Moreover, Suzuki’s hold on the purse strings enabled him to exercise leverage over his political boss. Drawing upon information from Uekusa Yoshiteru, who was also a secretary to Nakagawa before becoming a member of parliament, Katō alleges that Suzuki threatened to expose a scandal in Nakagawa’s campaign finances if Nakagawa did not support Suzuki’s bid to run in the general election of 1983 (Katō 2002: 16). Katō also claims that Suzuki may have been involved in the disappearance of funds that were left over from Nakagawa’s unsuccessful bid for the LDP leadership in November 1982. When Nakagawa was told by Suzuki on New Year’s Day that none of this money was left, Nakagawa is said to have become enraged and began punching Suzuki in the head (Katō 2002: 18). Just over a week later, Nakagawa was found dead in a hotel room in Sapporo, having seemingly taken his own life.

Nakagawa’s family held Suzuki responsible for driving the politician to his death. In particular, his wife, Sadako, claims that Suzuki not only ruined Nakagawa’s political career but also his private life (Katō 2002: 11). Moreover, she alleges that Nakagawa had shouted, “Suzuki, how dare you stab me like this! You’ve killed me. I’ve no choice but to die.” (quoted in Katō 2002: 18). In response, Suzuki retorts that Nakagawa was depressed after losing the LDP leadership election. He was also terrified that it was going to be revealed that he had received an illegal donation of one million yen from All Nippon Airlines. Added to this, Suzuki claims that Sadako herself added to the pressure on Nakagawa by threatening to divorce him if he did not sack Suzuki (J-Cast 2010).

After Nakagawa Ichirō’s death, Suzuki followed through with his plan to stand for election in December 1983. In so doing, he became a rival to Nakagawa Shōichi, the 30-year-old son of Nakagawa Ichirō, who had stepped into his father’s shoes. Under the system that operated until the reforms of 1994, all members of Japan’s House of Representatives were elected in multi-member constituencies by single non-transferable vote. This meant that members of the same party ran against each other in large constituencies, thereby encouraging factionalism within the dominant LDP. In the case of Suzuki and Nakagawa Shōichi, in the four elections between 1983 and 1993, they were opposing candidates in Hokkaidō’s 5th district, from which five Diet members were elected. On each occasion that the two men ran directly against each other, Nakagawa topped the polls, with Suzuki securing election as the fourth or fifth most popular candidate.

Even after the electoral reform of 1994, which created a mixture of single-member districts and a party list system with proportional representation (PR), Suzuki and Nakagawa remained rivals. This was because the LDP now needed to decide who would be its sole candidate in the new 11th district, where both men had their greatest concentration of support. Ahead of the election in 1996, the LDP leadership opted for Nakagawa. Suzuki also lost out in the 12th district, his second choice, where the LDP’s Takebe Tsutomu was judged the stronger candidate. He was eventually selected to run in the 13th district but lost heavily to the candidate from the New Frontier Party. Despite this, Suzuki was still able to return to parliament as a result of votes for the LDP within the Hokkaidō PR block (Carlson and Reed 2018: 73).

This long-term rivalry between Nakagawa Shōichi and Suzuki Muneo is another factor that makes Prime Minister Abe’s frequent meetings with Suzuki surprising. This is because Abe and Nakagawa Shōichi were very close. Nakagawa was one year older than Abe and they shared a nationalist agenda, with a common desire to promote patriotic education and a less apologetic attitude towards Japan’s wartime history. After Abe became prime minister for the first time in September 2006, he appointed Nakagawa as chair of the LDP’s Policy Research Council. Later, in September 2008, under the leadership of Asō Tarō, Nakagawa was appointed Minister of Finance, but served less than five months. In February 2009, Nakagawa, who was known for his heavy drinking, appeared drunk during a press conference at a G7 finance ministers’ meeting. He claimed that his drowsiness and slurred speech were due to a strong dose of cold medicine, but he was forced to resign within days. Nakagawa lost his seat in the general election of August 2009 and was found dead in his Tokyo apartment a few weeks later, after reportedly taking sleeping pills (Nakamoto 2009).

Suzuki’s accumulation of power

Despite his energetic campaigning and prowess as a fundraiser, Suzuki has never been especially successful electorally. As noted, under the system of multi-member districts, Suzuki consistently lagged behind Nakagawa Shōichi and was only ever the 3rd or 4th most popular LDP candidate within the Hokkaidō 5th constituency. What is more, after the electoral reform of 1994, he never succeeded in winning a single-member district, always being returned to parliament as a result of PR party votes.7 As such, Suzuki’s political power rested, not on his broad appeal with the voters, but on his steady accumulation of influence within the political system and especially over Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The leverage that Suzuki was able to exert over MOFA at the start of the 2000s was a consequence of a peculiarity in the Japanese political system. Although the foreign minister had nominal control over the ministry, in reality, many politicians holding this position owed their promotion simply to the fact that it was the turn of their LDP faction to receive a senior cabinet post. As a consequence, many Japanese foreign ministers had little international expertise and did not serve long enough to significantly shape foreign policy. Real control was exercised by senior MOFA bureaucrats, as well as by certain politicians, like Suzuki, who, no matter what their formal responsibilities, made a point of specialising in foreign affairs. These are known as the “policy tribesmen” (zoku giin) (Carlson and Reed 2018: 94-5).

The relationship that developed between Suzuki and MOFA was a reciprocal one. Specifically, Suzuki made himself valuable to senior diplomats by working within the political system to further the interests of the ministry, such as by arguing for the opening of new overseas missions and by pressing the Ministry of Finance to protect MOFA’s budget. In return, Suzuki expected to be consulted about key decisions and to play a hand in shaping foreign policy.

Suzuki’s influence was exerted covertly and only truly came to light following Prime Minister Koizumi’s appointment of Tanaka Makiko as foreign minister in April 2001. She is the daughter of Tanaka Kakuei, who served as prime minister between 1972 and 1974. Suzuki and Tanaka Makiko became major adversaries, but there are actually several similarities between Suzuki and her father. They both had relatively humble origins and rose to prominence through their mastery of backroom politics. In addition, both men closely associated themselves with the goal of directing public spending towards rural Japan. For this reason, Suzuki claims that he, rather than Tanaka Makiko, is the politician who really inherited Tanaka Kakuei’s spirit (Suzuki 2018: 118). Another thing that the two men have in common is that they were both found guilty of corruption and given prison sentences.

Tanaka Makiko’s appointment as foreign minister came at a time when MOFA was roiled by allegations of corruption. The most spectacular of several scandals was the case of Matsuo Katsutoshi, who was director of the Ministry’s Overseas Visit Support Division. At the beginning of 2001, it was revealed that, between 1993 and 1999, Matsuo had engaged in the widespread theft of funds that were intended for arranging overseas trips by the prime minister and other officials. Ultimately, Matsuo was arrested for having “used 410 million yen ($3.4 million) to purchase a yacht, condominium, golf club memberships, a string of racing horses, and to pay his mistresses and former wife” (Carlson and Reed 2018: 99). Although MOFA initially sought to portray Matsuo’s case as the crime of a single individual, Tanaka Makiko saw it as indicative of an institution that had evaded oversight for too long and had become “a hotbed of corruption” (quoted in Satō 2005: 98).

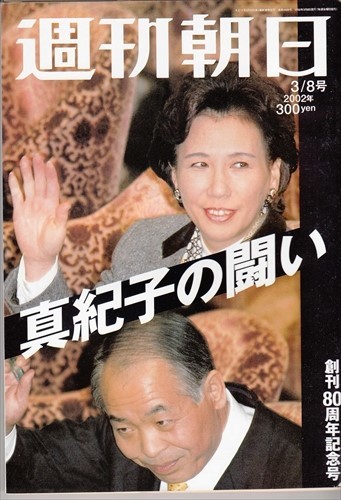

As Minister of Foreign Affairs, Tanaka immediately set out to reform the Ministry, putting her on a collision course with senior diplomats. The first sign of trouble came in May 2001 when senior MOFA officials made a series of personnel changes without consulting the minister. Determined to stamp her authority, Tanaka responded by freezing all personnel transfers (Carlson and Reed 2018: 99). Senior officials were appalled by this political interference and turned to Suzuki Muneo for assistance in countering her reform efforts. This set the stage for what Satō Masaru describes as “the Battle between Tanaka Makiko and Suzuki Muneo” (Satō 2005: 61).

|

Front cover of an issue of Shūkan Asahi (2002) with the title “Makiko’s battle” |

Suzuki clearly shared the objective of opposing institutional changes that threatened his steadily accumulated influence over the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. However, Suzuki and his allies were also opposed to Tanaka because of her attempts to alter the course of Japanese foreign policy. MOFA officials and Suzuki regarded themselves as international experts and did not want their carefully developed policies to be disrupted by Tanaka, whom they saw as a foreign policy neophyte.

The clearest example of this is with regard to Russia policy. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, under the administrations of Hashimoto Ryūtarō, Obuchi Keizō, and Mori Yoshirō, Suzuki and supportive MOFA officials developed a new approach to the territorial dispute with Russia. Up until this point, Japanese governments had consistently promoted what might be described as a principled approach to resolving the territorial dispute. This meant that Tokyo would continue to insist upon the immediate return of all four of the islands, or at least the demand that Moscow simultaneously recognise Japan’s right to sovereignty over all four. This position was maintained even though it was apparent that Japan’s refusal to compromise meant that there was no prospect of a breakthrough. The innovation put forward by Suzuki and his associates was to abandon the unrealistic goal of securing the return of all four of the islands in one go. Instead, they promoted a phased approach. In advance of the Irkutsk summit in March 2001, this crystallised as the proposal for a “two-plus-two” formula. This would see talks about a peace treaty and the transfer of the smaller islands of Shikotan and Habomai being conducted separately from negotiations about the future status of the larger islands of Kunashir and Iturup. Suzuki, as well as Tōgō Kazuhiko, who was then Director-General of MOFA’s European and Oceanian Affairs Bureau, and Satō Masaru, who was a leading Russia expert within MOFA, saw this compromise approach as the only means of achieving progress towards resolving the territorial dispute (Brown 2016: 117).

Believing that they were on the verge of a breakthrough, the Suzuki-led group was aghast when, shortly after taking office in April 2001, Tanaka proposed an entirely different strategy. She did this by suggesting a return to the hard-line demand for “the return of four islands as a bunch” that was pursued by her father when he met General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev in October 1973 (Satō 2005: 65). Since Suzuki and his allies were convinced that Tanaka’s retrograde approach would badly damage relations between Japan and Russia, taking action to oppose the minister was regarded as a necessary step to protect Japan’s national interests (Satō 2005: 103-5). These concerns were not without foundation since, after Tanaka Kakuei’s visit to Moscow in 1973, there were no further official meetings between the Soviet and Japanese leaders until Gorbachev travelled to Tokyo in April 1991. The Suzuki faction therefore feared that bilateral relations would be returned to the state of stagnation that had characterised the late-Cold War period.

Driven by these motivations, MOFA officials, in collaboration with Suzuki, sought to undermine the foreign minister. In these efforts, they were greatly assisted by Tanaka herself, who committed a series of gaffes. The first of these occurred in early May 2001 when, at the last minute, Tanaka cancelled a meeting with visiting U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage. Her critics leapt upon this incident as an indication of her unprofessionalism; they reported that the reason for the cancellation was because she was busy writing thank you letters to those who had sent flowers in congratulation for her ministerial appointment (Satō 2005: 97). Further leaks followed about other cancelled meetings and she was also attacked for accidentally revealing the location of where U.S. State Department officials were hiding after the terrorist attacks of September 11 2001 (Satō 2005: 122).

This battle between the foreign minister and her officials was largely played out in public, with Tanaka telling the media, “They are digging holes and placing landmines in front of me, apparently trying to get me out of the way so they can go back to doing things as they wish” (quoted in The Japan Times 2001). There were also bizarre incidents, such as when Tanaka returned to her office from a Diet session to find that one of her rings was missing. Reporters in a neighbouring room were able to record Tanaka accusing her administrative secretary Kozuki Toyohisa (who was appointed Japanese ambassador to Russia in 2015) of stealing the ring and ordering him to go to buy a replacement (The Japan Times 2001).

Another confrontation with bureaucrats related to the transfer of Kodera Jirō from his position as director of the Russian Division to the post of Japanese ambassador to the United Kingdom. Kodera was a supporter of the hardline stance on the territorial issue with Russia that was favoured by Tanaka. Suzuki therefore saw him as an obstacle to his preferred Russia policy and is therefore said to have used his influence to have Kodera transferred. However, as soon as Kodera arrived in London, he was immediately recalled by Tanaka and reappointed to his former position. Absurdly, Kodera spent only 3 hours in the UK before flying back to Japan. In revenge, Suzuki took the opportunity to grill Tanaka for two hours in parliament on Kodera’s recall and her broader Russia policy (Sayle 2002).

Ultimately, Prime Minister Koizumi had to step in to end this state of dysfunction within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The final straw was a conflict over invitations to the Tokyo Conference on Reconstruction Aid for Afghanistan in December 2001. Two Japanese non-governmental organisations (NGOs) — Peace Winds Japan and Platform Japan — were initially invited to the conference. However, when Suzuki learned that Ōnishi Kensuke, a representative of Peace Winds Japan, had criticised the government in a newspaper article, he allegedly instructed his allies within MOFA to exclude the NGO from the conference (Berkofsky 2002). Tanaka was furious about the barring of these NGOs, especially because, as she claimed, Vice Foreign Minister Nogami Yoshiji twice told her that MOFA had been forced to exclude the NGOs on the orders of Suzuki Muneo (Sayle 2002). Nogami denied that he had ever mentioned Suzuki’s name, and both he and Tanaka accused each other of lying. With Tanaka having lost all control of her ministry, Koizumi sacked her at the end of January 2002, while Nogami was demoted (Sayle 2002).

Suzuki’s victory proved short-lived since, less than two months later, he was forced to resign from the LDP. Nonetheless, Suzuki’s role in helping drive Tanaka from office demonstrates the extraordinary level of informal influence that he had amassed within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Indeed, this was later tacitly acknowledged by MOFA. After Suzuki’s arrest in 2002 and surprise reelection to the Diet in 2005, MOFA issued staff with a formal manual on how to deal with Suzuki in order to ensure that the controversial politician did not reestablish inappropriate levels of influence over the Ministry (Shūgiin 2009).

Japan’s key man in relations with Russia

|

Suzuki Muneo being received by Vladimir Putin at the Kremlin in April 2000 (Jiji) |

Further to his privileged connections within MOFA, Suzuki’s political power was established upon his reputation as a politician who is an expert on relations with Russia and the disputed Northern Territories. It is this expertise that has sustained Suzuki’s political influence over the years, enabling his Lazarus-like return from incarceration to the inner circle of the Japanese leadership. Although Suzuki’s actual achievements with regard to Russia are meagre, the failure of all Japanese governments over the last seven decades to make any progress on this issue makes Suzuki’s alternative approach and optimistic rhetoric seem enticing. Specifically, Prime Minister Abe evidently judged that Suzuki’s assistance was indispensable if he is to succeed in his goal of finally resolving the territorial dispute with Russia and signing a peace treaty.

Principally, Suzuki presents himself as the leading political representative of former Japanese residents of the four disputed islands. Prior to their occupation by Soviet forces at the end of the Second World War, the Japanese population of the four islands was 17,291 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2018). After being forcibly expelled from the territory by the Soviet Union, the majority of these individuals settled in Hokkaidō. By March 2019, only 5,913 of these former islanders remained alive and their average age was 84.1 (Ōno 2019). Despite their dwindling numbers, the plight of these individuals remains an emotive issue within Japan.

As a native of eastern Hokkaidō, where many of the former islanders reside, it was natural for Suzuki to associate himself with their cause. Suzuki was also quick to recognise that, for many of the former residents, what mattered most was not the principle of sovereignty over the islands but the practical matter of access. Suzuki’s promotion of a compromise solution therefore appealed to many. His so-called “two-plus-alpha” formula only promises the return of Shikotan and Habomai plus some form of access rights to Iturup and Kunashir (Takewata 2019).8 Nonetheless, the opportunity to freely visit their former homeland before the end of their lives is more attractive to many than the vague possibility of the return of all four islands, which might not be achieved for decades, if ever.

Added to this, Suzuki has long been a proponent of closer political and economic ties with Russia as a means of preparing the ground for a territorial deal, as well as a way of promoting regional development in Hokkaidō. In this respect too, Prime Minister Abe is heeding his advice. Central to Abe’s “new approach” to relations with Russia, which was announced in May 2016, is an 8-point economic cooperation plan, which prioritises enhanced bilateral ties in the areas of health, urban infrastructure, exchange between small and medium-sized enterprises, energy, industrial diversification and productivity, industrialisation of the Russian Far East, cutting-edge technology, and people-to-people exchange (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2016). Again, this represents a reversal of the approach taken by previous Japanese governments, which often held back economic cooperation until hoped-for progress on the territorial issue was achieved. Encouraged by Suzuki’s advice, Abe’s policy is instead to frontload economic investment in the hope that this will generate the needed momentum to deliver a territorial breakthrough (Brown 2018a: 1-5). To date, the biggest Japanese investment in Russia under the “new approach” is the purchase of a 10% stake in Russia’s Arctic LNG-2 project, which was announced in June 2019. The stake is worth more than $2bn and, while the Japanese consortium includes Mitsui & Co, 75% of the financing is being provided by state-controlled JOGMEC.

As the self-styled representative of the former islanders and with concrete ideas for resolving the dispute, Suzuki presents himself as the one politician who can finally facilitate a deal with Russia. Ahead of the upper-house election in July 2019, he told voters: “No matter what it takes, I want to resolve the Northern Territories problem. To do this, I want to return to parliament once again. Please everyone, once again give Suzuki Muneo the opportunity to work. Suzuki Muneo will not lose. I will win!” (quoted in Takewata 2019)

Central to Suzuki’s claim to be able to deliver a breakthrough are his long-standing connections within the Russian political elite. These were developed with the assistance of Satō Masaru, who has been a key figure in Suzuki’s rise, fall, and rehabilitation. During the 1990s, when Suzuki was extending his influence over the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Satō was a junior non-career diplomat specialising in Russian politics.9 The two men initially met during a trip to Moscow by Suzuki in 1990 and reportedly bonded over their shared dislike of career diplomats (Katō 2002: 38). These are the elite officials who dominate senior positions within MOFA and are usually graduates of Japan’s most prestigious universities. From this first encounter there developed an unusually close personal relationship, with Suzuki describing Satō as an “intellectual giant” (Suzuki 2019b) and Satō, in return, praising Suzuki for his “exceptional ‘grounded mind’” (Satō 2005: 49).

|

Suzuki Muneo and Satō Masaru |

Over the course of the next decade, Satō became Suzuki’s “private soldier” within MOFA (Katō 2002: 41). Suzuki used his influence to have Satō appointed to the specially created role of chief analyst within the first division of MOFA’s Intelligence and Analysis Bureau. From this position, Satō worked to further Suzuki’s foreign policy agenda and to provide him with information from within the Ministry. Tanaka, in her battle with Suzuki for control over MOFA, recognised the instrumental role that Satō played in facilitating the influence of her rival. In frustration, she began describing Satō as MOFA’s “Rasputin” and sought to marginalise him by having him transferred (Satō 2005: 126-7).

Satō knows the Russian language well and developed an impressive array of contacts during his time at the Japanese embassy in Moscow. He was therefore able to assist Suzuki in developing connections with the Russian political elite. As a consequence, when Suzuki was at the peak of his political power at the turn of the century, Russian officials visiting Tokyo would meet Suzuki for informal late-night discussions at which Satō, of course, was also present. One regular contact was Viktor Khristenko, who was first deputy prime minister from May 1999 to January 2000 (Satō 2005: 129). Also, when Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov visited Tokyo in February 2002, Suzuki and Satō, along with former Prime Minister Mori, met him for talks at a sushi restaurant in Roppongi the night before his official meeting with Foreign Minister Kawaguchi Yoriko, who had just replaced Tanaka Makiko. When they learned that the press were outside, Suzuki and Satō stayed behind in the restaurant to hide their presence, while the others left. As they were finally departing, they received a phone call from Russian ambassador Aleksandr Panov, who invited Suzuki to visit Ivanov’s hotel room for a frank discussion in preparation for the next day’s formal talks (Satō 2005: 143-4). This is evidence of the behind-the-scenes role that Suzuki was performing at the time.

Suzuki no doubt believes that these covert efforts were important in facilitating the development of Japan-Russia relations. Nonetheless, his activities with regard to the disputed islands and his close contacts with Russian officials have proved a continuing source of controversy.

To begin with, in line with his aim of maximising Japan’s involvement on the disputed territory, Suzuki has long been a proponent of Japanese investment and joint projects with Russia on the islands. This was Suzuki’s key focus during the late 1990s. Moreover, since soliciting Suzuki’s help in December 2015, Abe has also become a strong advocate of joint economic projects on the islands, agreeing with Putin in September 2017 to concentrate on five priority areas: aquaculture, greenhouse agriculture, tourism, wind power, and waste management (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2017).10 However, at least during the 1990s, Suzuki’s enthusiasm for promoting Japanese investment on the disputed islands led him into trouble.

One controversial incident occurred in May 1996 when Suzuki joined a visa-free exchange visit to the island of Kunashir. Suzuki, alongside a group of former Japanese islanders, for whom these visits are primarily intended, proposed to plant a number of Japanese cherry trees that they had brought with them as a symbol of peace and friendship. The local authorities agreed but insisted that the group complete the necessary quarantine procedures before the trees could be planted. Suzuki was willing to comply but a MOFA official, who was accompanying the group, refused, saying that completing the quarantine forms would imply acknowledgement of the Russian government’s jurisdiction over the disputed territory. It was therefore not possible for the cherry trees to be planted. Although the unnamed diplomat was simply following official procedure, Suzuki was furious. As Ignacy Marek Kaminski recounts,

“Suzuki had not only accused Mr. X of undermining his regional peace efforts, but he had also physically attacked Mr. X during the group’s return trip onboard the Japanese vessel. Although the official’s facial and leg injuries required a week to heal, the Foreign Ministry suppressed the incidents caused by Suzuki” (2004: 186).

The other main source of scandal was Japan’s provision of financial assistance to the islands by means of the so-called Cooperation Committee (shien iinkai). This entity was established within MOFA in 1993 as a vehicle for providing assistance to the territories of the former Soviet Union. This sounds uncontroversial. However, since the Cooperation Committee sat outside Japan’s usual structures for providing aid, its funds came to be used in an opaque manner for a range of other purposes.

Specifically, Suzuki is alleged to have used the resources of the Cooperation Committee to fund projects on the disputed islands that generated lucrative contracts for Hokkaidō businesses that were major donors to Suzuki himself. For instance, in June 1995, Suzuki successfully lobbied Foreign Minister Kōno Yōhei to approve construction of a medical facility on Shikotan.11 According to Kaminski, “The building contract was awarded to the contractor from Suzuki’s constituency, which was a regular contributor to Suzuki’s electoral fund.” (2004: 181). Kaminski also notes that, after Suzuki was promoted to the position of deputy chief cabinet secretary in 1998, “the overt economic aid to the Russian-occupied islands jumped from about 0.5 billion yen in 1998 to over 3 billion in 1999.” (2004: 183). The implication is that Suzuki used his enhanced leverage to direct more money from the Cooperation Committee to projects on the islands that would reward his political donors.

The most memorable of these projects is the so-called “Muneo House”, an emergency evacuation facility on Kunashir, which is properly known as the “Japan-Russia Friendship House.” It is alleged that, two months before the 417 million yen construction contract was awarded, “Suzuki conferred with the Foreign Ministry’s officials regarding the bidding requirements and procedures. On Suzuki’s request, the ministry illegally limited the contractors eligible to place the bids to those from Hokkaido’s Nemuro region and with certain business experiences in the past.” (Kaminski 2004: 183). It was subsequently reported that, between 1995 and 2000, the two successful contractors had donated over 9 million yen to Suzuki’s electoral support committee (kōen kai) (Kaminski 2004: 198).

|

“Muneo House” on Russian-held Kunashir (2012) |

Although the alleged chicanery regarding the building of “Muneo House” is the best-known scandal relating to Suzuki, it was not the leading factor in his arrest and imprisonment. Instead, Suzuki was sent to prison for crimes connected to two separate instances of bribery. The first case involved Suzuki’s acceptance in 1998 of 5 million yen from Yamarin, a lumber company, in exchange for Suzuki’s influence as deputy cabinet secretary in assisting the company to avoid punishment for illegal logging in national forests. Suzuki’s prosecution for perjury also relates to this case, since he was found guilty of lying about the Yamarin bribe during sworn testimony in a Diet committee hearing in March 2002.

The second bribery case involved Suzuki’s acceptance of 6 million yen from Shimada Construction between 1997 and 1998. Prosecutors successfully argued that these funds were a bribe that had been given to Suzuki, who was then head of the Hokkaidō Development Agency, in return for his help in winning government contracts (Carlson and Reed 2018: 71-2). Shimada Construction is also reported to have paid John Muwete Muluaka, Suzuki’s former Congolese private secretary, 15 million yen over a period of six years, despite the fact that “Big John”, as he is known, had done no work for the company. As Axel Berkofsky elaborates, “The affair became even more bizarre when it was revealed that Muluaka had been granted permanent residence in Japan in October 2001, even though his diplomatic and normal passports expired in 1994 and 1998 respectively.” (2002).

However, while the misuse of Cooperation Committee funds was not directly connected with Suzuki’s arrest, it was the cause of the downfall of his ally Satō Masaru. Specifically, Satō was arrested, and subsequently found guilty, of illegally procuring 30 million yen from the Cooperation Committee to pay for more than 10 Japanese academics and Foreign Ministry officials to attend a conference at Tel Aviv University in Israel. Since Cooperation Committee rules only permitted the funding of such events in Russia or other Soviet republics, this spending was deemed illegal. He was also accused of inappropriately using 3 million yen from the Cooperation Committee to pay for the visit of an Israeli researcher and his wife to Japan in January 1999 (The Japan Times 2002). Separately, Satō was accused of providing confidential information to a Japanese trading company about a construction contract on the Northern Territories (McCormack 2010: 2).

Tōgō Kazuhiko, who had moved from his position of Director-General of MOFA’s European and Oceanian Affairs Bureau to become Japan’s ambassador to the Netherlands, was also caught up in the scandal. He was forced to resign from the Ministry in April 2002 and then in Europe he was interviewed by prosecutors in relation to the same charges as Satō. However, since Tōgō avoided returning to Japan until 2006 – when he testified on Satō’s behalf – he was never arrested.

As with Suzuki, Satō has subsequently made a remarkable comeback. After being suspended (and later sacked) from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Satō began a phenomenally successful career as an author, writing countless books and articles on a wide range of topics and becoming an influential public intellectual. Satō also retains close ties with Suzuki and has regularly appeared alongside him at public events organised by Shintō Daichi, Suzuki’s political movement. Satō has also made a significant contribution to laundering Suzuki’s reputation. This he achieved by writing Kokka no Wana [The Trap of the State] in 2005. This book, which became a bestseller in Japan, convincingly argues that Satō was harshly treated for what were, at most, administrative misdemeanours and which certainly did not merit pre-trial detention of 512 days. What is more, the book provides a favourable account of Suzuki’s character and intentions in his exercise of influence over the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Satō 2005: 62-128).

Aside from the controversy arising from the use of Cooperation Committee funds and promotion of projects on the disputed islands, Suzuki’s ties with Russian officials have also periodically raised concerns. For example, Kaminski mentions rumours of Suzuki’s contacts with Russian intelligence operatives. Specifically, he claims that “Suzuki had private meetings with a certain Smirnov of the Russian embassy in Tokyo. Suzuki was aware that Smirnov was an intelligence officer. But he pressured the head of the National Police Agency (NPA) not to pursue his meetings with Smirnov.” (2004: 191).

Such reports might seem alarming but it is important to emphasise that there is no evidence to suggest that Suzuki ever knowingly served the interests of the Russian state. The intelligence services play a prominent role in Putin’s Russia and Suzuki may simply have judged that meeting intelligence officers is a necessary step in the process of cultivating a network of valuable contacts within the Russian political system. Nonetheless, there remain legitimate concerns about Suzuki’s Russian connections. He has pro-Russian inclinations, a history of criminality, and regular access to Prime Minister Abe. This trinity of factors may have encouraged the Russian intelligence services to view Suzuki as a security vulnerability that can be exploited. Moreover, even if this is not the case, it is certain that Russian officials will seek to use their contacts with Suzuki as a means of projecting influence into the prime minister’s office in an attempt to ensure that the Japanese leader continues to pursue a Russia policy that is deemed favourable to Moscow.

What Suzuki’s return says about Japanese politics more broadly

The magnitude of Suzuki Muneo’s rise, fall, and rise again is unique. Even Suzuki himself talks of three “miracles” (Suzuki 2019e). The first was his initial election to the lower house in 1983; the second was his re-election in 2005, which occurred after his arrest, but prior to his official sentencing; and the third was his election to the upper house in July 2019. Yet, even though there is no politician quite like Suzuki Muneo, there are some broader conclusions about Japanese politics that can be drawn from his extraordinary case.

Firstly, and most obviously, the return of Suzuki suggests a high degree of tolerance for a certain type of corruption within Japan. Although his conviction has been upheld in Japan’s Supreme Court and his demand for a retrial rejected, Suzuki has never accepted responsibility for his crimes, nor has he apologised. Despite this, many Japanese voters, as well as the media and broader political class, appear willing to forgive and forget. This relaxed attitude towards graft also appears to include Prime Minister Abe since he began to invite Suzuki to the Kantei in 2015, when the convicted politician was still banned from political office. Abe’s only nod to propriety has been his refusal (so far) to permit Suzuki to rejoin the LDP.

It is not easy to immediately identify why there should be such acceptance of Suzuki’s behaviour in Japan, whereas similar actions in many liberal democracies would be sufficient to end a political career many times over. One consideration, however, is the fact that the Suzuki scandals do not primarily relate to accusations of personal enrichment. Instead, Suzuki was essentially found guilty of developing a symbiotic relationship with companies in Hokkaidō through which he assisted them to win business and, in return, they provided him with financial resources to keep him in power. This is a perversion of the proper function of the democratic process and can therefore be regarded as corruption (Carlson and Reed 2018: 15-6). Nonetheless, some Japanese voters may simply consider that Suzuki was performing his proper role of serving the interests of his constituency. This is consistent with Miyamoto Masafumi’s broader observation that, in Japan, the “public perceives corruption as a victimless crime and dismisses the affair” (quoted in George Mulgan 2010: 194).

Acceptance of corruption as a normal part of the political game is therefore one structural factor that appears to have facilitated Suzuki’s return to power. However, the other lessons from the Suzuki case relate to qualities embodied in Suzuki himself. There are three of these: the ability to connect oneself to powerful political patrons; the possession of policy expertise; and personal charisma.

First, Suzuki’s success demonstrates the reliable benefits of tying oneself to influential individuals and, when necessary, engaging in outright sycophancy. After Nakagawa Ichirō’s suicide, Suzuki cultivated ties with Kanemaru Shin, an important LDP powerbroker from Yamanashi prefecture. According to Berkofsky, “He [Suzuki] and Koichi Hamada, another independent in the LDP, acted as Kanemaru’s bodyguards and often served as Diet hecklers during Kanemaru’s tenure as LDP Secretary General” (2002). Kanemaru was a central figure in the Sagawa Kyūbin scandal that broke in 1992 in which he was alleged to have received a 500 million yen bribe from the parcel delivery firm, which he then shared with around 60 other LDP politicians. Prosecutors also accused Kanemaru of tax evasion amounting to over one billion yen. When his home and offices were searched, investigators discovered a hoard of cash, bearer bonds, and 220 pounds of gold bars. Although he was arrested, Kanemaru’s trial was suspended due to his poor health and he died in 1996 (Carlson and Reed 2018: 54-6).

Subsequent to Kanemaru’s downfall, Suzuki prioritised relations with Nonaka Hiromu, who served as Chief Cabinet Secretary between 1998 and 1999. He also became close to Mori Yoshirō, who Nonaka helped to make prime minister in April 2000. In developing these connections, Suzuki endeared himself by sharing his financial resources. Specifically, “Over a two-year period from 1997-1999, he contributed a total of 39 million yen to 11 LDP lawmakers, including members of the current Koizumi cabinet, senior vice ministers and parliamentary vice-ministers.” (Berkovsky 2002).

As the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) prepared to take power after the general election in August 2009, Suzuki set aside his long-term connections with the LDP and strengthened ties with the new government of Hatoyama Yukio. This immediately paid dividends when he was appointed chair of the lower house committee on foreign affairs. This was despite the fact that Suzuki was still on trial for bribery. Suzuki again sought to make himself useful with regard to both Russia policy and Okinawa, but in September 2010 his conviction was upheld and he was sent to prison.

After his release on parole in December 2011 and the LDP’s return to power a year later, Suzuki shifted his allegiance to the Abe administration and increasingly sought to align his statements with government policy. This involved reversing his position on the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which he had previously criticised as a neo-liberal policy and harmful to farmers in Hokkaidō. Suzuki has also not been shy about personally praising key figures in the Abe government, saying, for example, that “I greatly appreciate the skill and ability of Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga, who continues to achieve excellent results.” (Suzuki 2019a). Additionally, despite supposedly representing an opposition party, Suzuki acclaims Abe as the only leader who can resolve the territorial dispute with Russia. He also asserts that “I have 1000 percent trust in Prime Minister Abe’s foreign policy towards Russia and I want him to make full use of my personal connections, information, and experience.” (quoted in Sankei Shinbun 2019b).

Such relentless courting of the powerful has been a key element of Suzuki’s success, yet his constant shifting of allegiances would not have been tolerated if he did not have something to offer in return. At times, this has been financial but, above all, Suzuki has used his expertise on Russia as his main currency of exchange. Suzuki’s knowledge of Russia and his web of personal contacts in the country are a rare commodity within Japanese politics and have made him valuable to a succession of Japanese leaders. This certainly applies to Abe, who is unlikely to have given Suzuki the access to the prime minister’s office that he enjoys, if the same expertise were available from a less controversial source.

Indeed, so rewarding has been Suzuki’s association with Russia that it is surprising that more members of the Japanese parliament have not followed him in cultivating a particular bilateral relationship. In the current Diet, the only other politician who stands out for his especially well-developed ties with a specific country is Nikai Toshihiro, the LDP secretary general, who is known for his contacts in China.

Adding to the appeal of Suzuki’s expertise on Russia is that, irrespective of his real motivations, his approach to the territorial dispute is logical. In particular, having studied the dispute, it is hard to disagree with Suzuki’s assertion that the principled approach of demanding Russia’s recognition of Japanese sovereignty over all four of the islands has failed and that the only plausible solution is a compromise that would see, at most, the transfer to Japan of the two smaller islands of Shikotan and Habomai, plus some form of enhanced access to the larger two islands (Sankei Shinbun 2018). This realism regarding the territorial issue is again something that has contributed to Suzuki’s relations with Japanese leaders, especially prime ministers Mori and Abe.

Lastly, in addition to the benefits of associating oneself with powerful figures and accumulating country-specific expertise, Suzuki Muneo’s enduring success demonstrates the value of charisma in Japanese politics. While Suzuki is generally a divisive figure, everyone can at least agree that, unlike many of his colleagues in Japanese politics, he is not boring. In part, this is a consequence of his natural effusiveness, but he is also skilled at self-promotion. One notable factor is the speaking style that he has cultivated, which, according to Murray Sayle, “advertises his provincial roots and an exaggerated humility rising to high-pitched yelling that suggests either a hair-trigger temper or the feigned rage of a samurai warrior as seen in Japanese TV serials.” (2002). He has also increased his visibility by adopting a signature item of clothing – a lime-green necktie – that he is rarely seen without. Additionally, he has made effective use of his friendship with Matsuyama Chihara, a popular singer from Ashoro, Hokkaidō, who campaigned for Suzuki ahead of the 2019 election. More surprising is that, during the same campaign, Suzuki also secured the endorsement of Steven Seagal, a Hollywood actor who starred in martial arts films during the 1980s and 1990s, before becoming a Russian citizen in 2016 (Suzuki 2019).

|

Steven Seagal and Suzuki Muneo during the 2019 upper-house election campaign (Twitter) |

Some of these traits might be regarded as populist, especially Suzuki’s embrace of common language to signal his identity as a champion of the ordinary Japanese people. In any case, in the sometimes dull world of Japanese politics, Suzuki’s distinctive character and active self-promotion have been important in helping him overcome his inauspicious start in politics, whereby he lacked the established network of support that is available to hereditary politicians. It was also this charisma that made the Suzuki-Tanaka battles of the early 2000s so captivating to a Japanese TV audience. In the case of both these politicians, the excitement generated by their theatrical performances appears to have encouraged the Japanese public to take a forgiving attitude towards their obvious failings.

Conclusion

This article has charted the remarkable political career of Suzuki Muneo over the past four decades. This has seen his progression from the humble role of secretary to Nakagawa Ichirō to the heights of being appointed deputy chief cabinet secretary in the administration of Obuchi Keizō. Emphasis was also placed on the extraordinary influence that Suzuki exercised over the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and on his very public battle with Foreign Minister Tanaka Makiko during the early 2000s. A prominent feature of the article has also been the numerous allegation of corruption and misconduct that have been directed at Suzuki over the years, as well as the crimes of bribery, perjury, and violation of political funding laws for which he was eventually sent to prison.

The ability of Suzuki to regain access to the prime minister’s office and to achieve re-election in 2019, despite his criminal record, is unprecedented in modern Japanese political history. Nonetheless, some broader conclusions have been possible. Namely, the Suzuki case suggests a significant degree of tolerance for corruption within Japan, especially when the crimes are judged to be to the benefit of the local constituency and not motivated by the desire for personal enrichment. Additionally, as is perhaps true of all political systems, Suzuki’s enduring success points to the importance of cultivating ties with powerful politicians, of becoming the go-to expert on a valued subject, and of bringing sparkle to the political arena.

Suzuki campaigned for election to the upper house in 2019 under the slogan that this was to be “Suzuki Muneo’s last battle” (Suzuki 2019e). Suzuki turned 71 in January 2019. By the standards of Japanese politics, this is not especially old, but the unfortunate return of his cancer of the oesophagus may have caused him to assess that his days in politics were numbered.

Despite this, it is too early to write the final chapter of Suzuki’s political biography. The reason for this is that Prime Minister Abe has fully adopted the Russia policy that Suzuki has advocated since the late 1990s and is implementing it in close consultation with the veteran politician himself. As noted, this entails expanding political and economic ties with Russia, as well as moving away from the demand for the return of all four islands and instead emphasising the goal of securing the transfer of just two. Abe’s embrace of this agenda was signaled by his agreement in November 2018 to base peace treaty talks with Russia on the countries’ 1956 Joint Declaration. This document promises the transfer of Shikotan and Habomai after the signature of a peace treaty, but makes no mention whatsoever of the larger islands of Iturup and Kunashir. Furthermore, Abe has fully signed up to Suzuki’s long-favoured agenda of promoting joint economic projects on the disputed islands. In December 2016, when Putin visited Abe in his home prefecture of Yamaguchi, the leaders agreed to discuss such projects. Having subsequently narrowed the focus to five priority areas, it was agreed in June 2019 that pilot projects would begin in the areas of waste management and tourism. The first of these trials took place in August 2019 when four Russian officials visited the Nemuro area of Hokkaidō to learn about Japan’s experience of waste management. The second is planned for October 11-16, when 35 Japanese, including officials, will visit Kunashir and Iturup on a trial tourism excursion. Given Suzuki’s influence in convincing Abe to adopt this approach, it is perhaps appropriate that, during their stay on Kunashir, the tourists are likely to stay in the “Muneo House” (Hosokawa 2019).

All of the indications are that Muneo’s agenda will not enable Abe to deliver the legacy-defining resolution to the territorial dispute that he is aching to achieve. This is because the Russian side appears to consider even the prospect of transferring the two smaller islands as excessive. Indeed, since Abe conceded in November 2018 to making the 1956 Joint Declaration the basis for talks, Russia’s position has only hardened. Specifically, the Russian leadership has made it clear that the transfer of two islands as a gesture of goodwill could only occur if Japan were first to accept Russia’s legitimate right to all four of the islands as a result of Soviet victory in World War 2. Added to this, Moscow would require legal assurances that no U.S. military facilities would ever be permitted on the transferred territory (Brown 2018b). As the Russian leadership well knows, no Japanese prime minister could easily accept these conditions. The impression is therefore that Moscow merely intends to accept the fruits of Abe’s engagement, without offering anything concrete in return.

And yet, given Suzuki’s extraordinary return from the political wilderness, as well as Abe’s own remarkable comeback after his failure as prime minister in 2006-07, perhaps we should not entirely rule out the possibility that the pair’s plan will succeed. Suzuki evidently believes that he has defied the political odds on several occasions already and can do so again. If he is right and can mastermind extracting an acceptable territorial deal from the Putin administration, Suzuki will have performed his greatest miracle of all.

List of works cited:

Berkofsky, Axel, 2002, “Corruption and Bribery in Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs: The Case of Muneo Suzuki,” Japan Policy Research Institute, JPRI working paper no.86, June.

Brown, James D.J., 2016, Japan, Russia and their Territorial Dispute: The Northern Delusion (London: Routledge).

Brown, James D.J., 2018a, “The Moment of Truth for Prime Minister Abe’s Russia policy,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, vol.16-10(5), 15 May.

Brown, James D.J., 2018b, “The high price of a two-island deal,” The Japan Times, 16 November.

Carlson, Matthew M. and Reed, Steven R., 2018, Political Corruption and Scandals in Japan, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press).

George Mulgan, Aurelia, 2010, “The perils of Japanese politics,” Japan Forum, 21(2): 183-207.

Hokkaidō Shinbun, 2019a, “Maruyama-shi, sake ni nomarebōsō, [Maruyama’s drunken rampage]” 31 May.

Hokkaidō Shinbun, 2019b, “18-nichi ni san’in-sen handan Suzuki Muneo-shi [Suzuki Muneo to decide on 18th whether to run in upper-house elections]“, June 1.

Hosokawa Shinya, 2019, “Yontō shiken tsuā 35-nin kibo [Test tour to the four islands will have capacity of 35]” Hokkaidō Shinbun, 17 August.

The Japan Times, 2001, “Tanaka cries foul at bureaucrats, urges teamwork,” 5 November.

The Japan Times, 2002, “Prosecutors grill Togo on funds scandal in Europe,” 12 June 2002.

Kaminski, Ignacy Marek, 2004, “Applied anthropology and diplomacy: Renegotiating conflicts in a Eurasian diplomatic gray zone by using cultural symbols,” ch.10 in Langholtz, H.J. and Stout, C.E. (eds.) The Psychology of Diplomacy, (London: Praeger).

Katō Akira, 2002, “Suzuki muneo kenkyū [Researching Suzuki Muneo]”, (Tōkyō: Shinchōsha).

McCormack, Gavan, 2010, Ideas, identity and ideology in contemporary Japan: The Sato Masaru phenomenon,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, vol. 8, issue 44(1): 1-22.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2016, “Japan-Russia Summit Meeting,” 7 May.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2017, “Japan-Russia summit meeting,” 7 September.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 2018, “Nihon no ryōdo o meguru jōsei [About the situation on Japanese territory],” 11 July.

Nakamoto, Michiyo, “Former Japan finance chief found dead,” The Financial Times, 4 October 2009.

Nikkei, 2019, “Nichiro 2 purasu 2, 5 getsumatsu kaisai o teian Roshia [Russia proposes that Japan-Russia 2+2 is held in late May],” 11 April.

Ōno, Masami, 2019, “Hoppōryōdo, 2-shima henkan ni kaji kiru shushō [Northern Territories: Prime Minister has shifted to seeking return of two island],” Asahi Shinbun, 17 July.

Sankei Shinbun, 2018, “Suzuki Muneo-shi nichiro kōshō ‘2-tō purasu a’ ga genjitsu-teki kaiketsu e no michi [Suzuki Muneo on Japan-Russia talks: ‘2 plus alpha’ is the path to a realistic solution]” 18 October.

Sankei Shinbun, 2019a, “Suzuki Muneo-shi ni saishin mitomezu Tōkyō chisai kettei bengo-dan, sokuji kōkoku e, [Tokyo District Court decision does not allow Suzuki Muneo retrial, lawyers to immediately appeal],” 20 March.

Sankei Shinbun, 2019b, “Suzuki Muneo Nihon ishin no kai San’in giin Hoppōryōdo shōten wa 9 gatsu kaidan [Suzuki Muneo, member of upper house from Nippon Ishin no Kai: Northern Territories – Focus on September talks],” 9 August.

Satō Masaru, 2005, Kokka no Wana [The Trap of the State], (Tōkyō: Shinchōsa).

Satō Masaru, 2019, “Maruyama Hodaka giin no ‘sensō’ hatsugen, nichiro kōshō ni an’un [Diet member Maruyama Hodaka’s ‘war’ comments pose a threat to Japan-Russia talks]” Nippon.com, 22 May.

Sayle, Murray, 2002, “The Makiko-Junichiro Show,” Japan Policy Research Institute, JPRI working paper no.89, October.

Shūgiin, 2009, Shitsumon honbun jōhō [Question text information], 4 June.

Suzuki Muneo, 2012, Seiji no Shuraba [Political Carnage] (Tōkyō: Bungei Shunjū).

Suzuki Muneo, 2018, Seiji Jinsei (Political Life), (Tōkyō: Chūōkōron Shinsha).

Suzuki Muneo, 2019a, “Hana ni mizu hito ni kokoro,” official blog, 12 June.

Suzuki Muneo, 2019b, “Hana ni mizu hito ni kokoro,” official blog, 27 June.

Suzuki Muneo, 2019c, “Hana ni mizu hito ni kokoro,” official blog, 14 July.

Suzuki Muneo, 2019d, “Hana ni mizu hito ni kokoro,” official blog, 21 July.

Suzuki Muneo, 2019e, “Hana ni mizu hito ni kokoro,” official blog, 22 July.

Tanewata, Yoshiki, 2019, “Suzuki muneo, saigono tatakai [Suzuki Muneo’s last battle],” NHK, 31 July.

Togo, Kazuhiko, 2011, “The inside story of the negotiations on the Northern Territories: five lost windows of opportunity,” Japan Forum, 23(1): 123-145.

Notes

To be precise, the disputed territory consists of three islands, which are known as Iturup, Kunashir, and Shikotan in Russian, and Etorofu, Kunashiri, and Shikotan in Japanese. There is also a small group of islets known collectively as the Habomais. For simplicity, this latter archipelago is customarily referred to as a single island, making it a “four-island dispute”.

Specifically, during the visa-free visit to Kunashir on 11 May 2019, Diet member Maruyama Hodaka is reported to have drunk more than 10 shots of cognac. He then became disorderly and raised the prospect of Japan going to war to seize the disputed islands. It is also alleged that he said that he wanted to “buy” a Russian woman (Hokkaidō Shinbun 2019a).

Suzuki Takako first entered parliament in 2013 as a candidate for Shintō Daichi. This followed the resignation of the party’s representative Ishikawa Tomohiro following a political funding scandal. She then joined the Democratic Party (DP) and was returned to the lower house in the election of December 2014. She left the DP again in 2016, making the LDP her third political party by the age of 31.

Katō Akira questions the extent of Suzuki’s childhood poverty, suggesting that he has exaggerated his family’s hardship in order to bolster his image as a self-made politician and representative of the common man (Katō 2002: 93-5).

In the elections of 1996 and 2000, Suzuki was elected to the House of Representatives as a candidate of the LDP in the PR Hokkaidō block. During the election of November 2003, Suzuki was in pre-trial detention (which lasted a total of 437 days) and unable to stand, but he returned to the lower house in 2005 through PR votes for Shintō Daichi, his own political vehicle. He was elected again in the same way in August 2009, but was forced to relinquish his seat when he was sent to prison the next year. Suzuki was banned from political office during the lower house elections of 2012 and 2014, and failed in his bid for election in October 2017. After switching to Nippon Ishin no Kai, he was successfully elected to the upper house through PR party votes in the election of July 2019.

The “two-plus-two” and “two-plus-alpha” proposals are similar, and both have been promoted by Suzuki Muneo. “Two-plus-two”, which was emphasised at the time of the Irkutsk summit in 2001, aims for the transfer of two islands to Japan, plus the continuation of talks about the other two. “Two-plus-alpha”, which appears to be Abe’s current goal, implies the transfer of two islands to Japan, plus some form of special access rights and joint economic projects for Japan on the other two islands.

In fact, prior to being steered towards Russia by MOFA, the scholarly Satō Masaru’s main area of interest was church-state relations in Czechoslovakia (Satō 2005: 17).

The proposed joint economic projects on the disputed islands are entirely distinct from Abe’s 8-point economic cooperation plan, which applies to Russia as a whole.