|

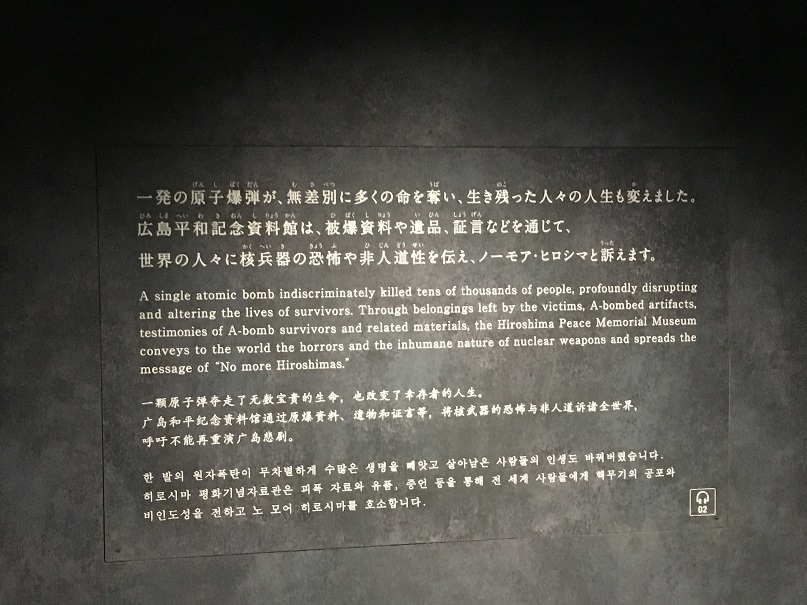

I first visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in 1981 on my initial trip to Japan. The displays at the museum have been renovated twice since, for the 1995 fiftieth anniversary of the atomic bomb, and most recently in April 2019.1 This article examines the three presentations about the bombing exhibited there in light of the shifting historiography.2

History Lite

The 1981 version, presented in a relatively modest facility that has since been greatly expanded, gave a bare bones account that conveyed the impression that the atomic bombing came out of the blue, like an unpredicted and unprecedented natural disaster. There was no context regarding the war or the previous firebombing of 64 Japanese cities, and no reference to the subsequent Nagasaki bombing. The displays focused exclusively on the horrific consequences for the city and its people. Uncomplicated by any analytical interpretation, the scenes of devastation were viscerally powerful. This version reflected the broader embrace of a victim’s narrative that emphasizes what happened to Japan. It largely overlooked what Japan had perpetrated across Asia from 1895-1945 and the wartime elite’s decision to plunge the nation into a reckless war of aggression in China, Asia, and the Pacific from 1937, and the escalating tension between the US-Japan that led to the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.3 The campaign to subjugate China and the subsequent widening of the war to Southeast Asia in the name of Pan Asian liberation claimed at least 15 million lives and displaced countless other millions. In the 1980s, there was a very incomplete reckoning about Japan’s rampage in Asia, although at that time many Japanese, including celebrated historian Ienaga Saburo, were contesting that absence. Ienaga challenged the Ministry of Education’s censorship in several court cases, but the government remained resolute about keeping the blinkers on regarding the Nanjing massacre and other atrocities that he wanted to include in his textbooks.4 He thought it the height of folly to censor such events from the official narrative—not least because doing so was reminiscent of the wartime era– and sought to draw the collective gaze to the horrors of war beyond Japanese suffering.

The Heisei Awakening

The historiographical awakening occurred after Emperor Showa’s (Hirohito) death in 1989. While he was alive it was difficult to criticize a Holy War fought in his name. Suddenly in the early 1990s the archives yielded their secrets, soldiers and officials discovered their diaries, previously marginalized accounts came to the fore and the media conducted a vigorous public debate about the baleful consequences of Japanese aggression. The mainstream consensus shifted towards a more forthright reckoning and emulated Germany on assuming responsibility and making gestures of contrition. This was part of a larger effort to improve relations with Asian nations that had suffered from Japanese imperialism.

This early Heisei consensus was expressed in the 1993 Kono Statement on one particularly ugly aspect of the war, in which Kono Yohei, the chief cabinet spokesman of the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) government, affirmed that: “the then Japanese military was, directly or indirectly, involved in the establishment and management of the comfort stations and the transfer of comfort women. The government study has revealed that in many cases they were recruited against their own will, through coaxing, coercion, etc., and that, at times, administrative/military personnel directly took part in the recruitments. They lived in misery at comfort stations under a coercive atmosphere … Undeniably, this was an act, with the involvement of the military authorities of the day, that severely injured the honour and dignity of many women.” After establishing that position, Japan made good on Kono’s promises to educate Japanese youth about this sordid saga and to engage in acts of contrition, incorporating comfort women into all the secondary school textbooks and launching the Asia Women’s Fund to offer solatia for former comfort women.

Moreover, from the early 1990s Emperor Akihito, who abdicated in April 2019, began a series of visits to Asian nations to pray for the souls of fallen Japanese soldiers and at the same time offer remarks of remorse and acts of contrition to victims of Japanese aggression. This was the unfinished business of his father’s reign that he pursued with energy and conviction throughout the Heisei era (1989-2019). Akihito served with distinction as Japan’s chief emissary of reconciliation and did more than all of Japan’s political leaders combined in building bridges and enhancing the dignity that had eluded a nation in denial.

This dramatic shift towards a more humble and contrite view of Japan’s shared imperial and wartime history with Asia and belated apology, influenced the 1995 Hiroshima narrative. Additionally, as Robert Jacobs, professor at the Hiroshima Peace Institute, Hiroshima City University, explains, “a driving force behind the revision in 1995 was the Asian Games being hosted here in 1993. During that event, many Korean and Chinese visited the museum and it came under very heavy criticism for the omission of any context to the attack. While the timing may have corresponded to the change in Imperial eras, here, people always talk about that revision as a response to the games and the increase in tourism it heralded.” (Personal communication July 2019)

Unlike the decontextualized narrative it replaced, the 1995 version prominently displayed diorama and explanatory panels near the entrance of the exhibit space that extablished and clarified the wartime context. Visitors learned that Japan had engaged in imperial aggression in China and elsewhere, and that the city was a military headquarters for troops involved in those campaigns and was engaged in military-related manufacturing. Wall panels showed that in addition to Japanese civilians, tens of thousands of soldiers and Koreans, including forced laborers, were among the A-bomb casualties and the hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors). Certainly, one could quibble about the content of these panels, but they did offer important context crucial to understanding the military nature of the city at the time of the atomic bombing, something that previous visitors would have had to find out by themselves. The added context is helpful since this museum is the most visited site for school trips in all Japan, and a major tourist destination, thus serving as an important forum for educating Japanese youth and other visitors.5 One still encountered the horrors of the atomic bombing, and the anti-nuclear message was unmistakable, but Japan was also implicated for instigating a war that provoked the nuclear nightmare. The exhibit also hinted at local anger that Hiroshima paid so disproportionately for decisions made in Tokyo. Yet for some visitors, the contextualization veered uncomfortably close to a rationalization for an atomic inferno that claimed 140,000 lives by the end of 1945 and left central Hiroshima in ruins. The more nuanced narrative incorporated a mea culpa too far for those who preferred the less complicated victim’s narrative undiluted by inculpation.

Revisionist backsliding

The historical revisionist movement in Japan since the mid-1990s taps into and stokes what can be called “perpetrator’s fatigue.” The cascade of damning history that followed the death of Emperor Showa generated a sharp backlash as conservatives eager to promote an exculpatory and valorizing history have fought back. Now none of the mainstream textbooks include mention of the comfort women and revisionists’ views on Japan’s war crimes and responsibility emanate from the Abe Cabinet. As Japan’s political center of gravity shifted rightward since the turn of the century, an exonerating and validating narrative has gained momentum, undermining the early Heisei consensus. Emperor Akihito remained steadfast in support of distancing postwar from wartime Japan and thus as the political context changed, he found himself an inadvertent dissident, an outspoken advocate for reconciliation. Due to Akihito’s prominent sparring with Prime Minister Abe Shinzo over history issues, subtly rejecting the vindicating narrative favored by the revisionist camp, he became an awkward exemplar for the monarchist right. They bridle at his boycott of the Yasukuni Shrine, ground zero for an unapologetic stance on Japan’s wartime record displayed in full in the historical exhibits at the adjacent Yushukan Museum.6 Emperor Showa began the boycott in 1978 when it became known that 14 class A war criminals had secretly been enshrined at Yasukuni, making it a sacred place to venerate those deemed most responsible for leading Japan into the war. Yasukuni’s head priest had to step down in 2018 after excoriating the Imperial Household and Crown Prince Naruhito and his wife in a weekly magazine, for shunning the shrine and—in his view– not properly respecting Shinto rites. Based on his public comments, it appears likely that Emperor Naruhito will maintain this imperial boycott in the Reiwa era and continue his father’s repudiation of revisionists’ fabulist reimagining of Japan’s wartime and colonial record.7 This now three-generations of imperial preference for reconciliation gets extensive media coverage and serves to highlight the important work of many progressive pundits and intellectuals who have engaged conservative efforts to rehabilitate Japan’s wartime history. The three emperors have used their prominence to parry revisionist whitewashing, a contrast most memorably captured in the speeches given by Abe and Akihito in August 2015 commemorating the 70th anniversary of Japan’s defeat.

Abe Statement 2015

In his speech, Prime Minister Abe was vague where he needed to be forthright – on colonialism, aggression, and the “comfort women” system – and came up short in expressing contrition by invoking apologies made by his predecessors without offering his own. Furthermore, Abe called for an end to apology diplomacy. Thus, the Abe statement represented significant backsliding from those issued by former prime ministers Murayama and Koizumi in 1995 and 2005, which had helped Japan and its victims regain some dignity while promoting reconciliation.

Noting the deaths of innocent Asians across the region, including 3 million Japanese, Abe dog- whistled: “The peace we enjoy today exists only upon such precious sacrifices. And therein lies the origin of postwar Japan.” This assertion that wartime sacrifices begot contemporary peace is a revisionist conceit, one that is conveyed in books and museums dedicated to sustaining the myth that Japan fought a noble war of Pan-Asian liberation and that the horrors endured were worthwhile.

Emperor Akihito spent much of 2015 repudiating this “Abenesia,” making pointed comments on several occasions about the need to address wartime history with persistence and humility. He offered a veiled rebuke on August 15, 2015, when he said, “Our country today enjoys peace and prosperity, thanks to the ceaseless efforts made by the people of Japan toward recovery from the devastation of the war and toward development, always backed by their earnest desire for the continuation of peace.” Peace and prosperity, in the emperor’s view, did not come from treating either the Japanese people or other Asians like cannon fodder during the war, but rather was based on their postwar efforts to overcome the needless tragedy inflicted by the nation’s militarist leaders. He forcefully advocated a pacifist identity as the foundation for today’s Japan, one that still resonates widely in Japan, challenging Abe’s agenda of transforming Japan into a “normal nation,” free from constitutional constraints on the military.8

The history wars are thus still being fought with intensity over whether Japan instigated an unjustifiable maelstrom for which it has much to answer for or fought a noble defensive war in the name of liberating Asian colonies from western rule. It is this debate that is relevant to assessing the 2019 Hiroshima narrative.

|

Hiroshima Revisionism: Honored and Subverted

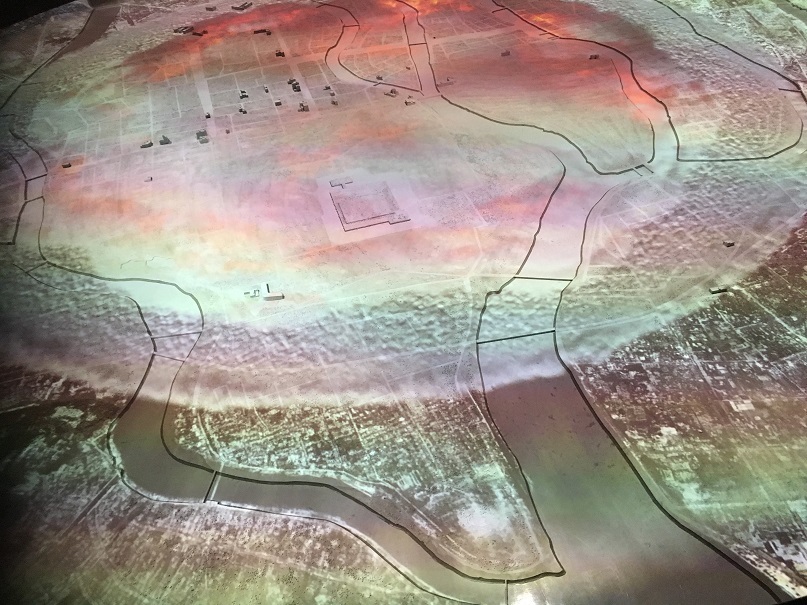

The newly renovated facility is gleaming and designed with Japanese panache. One ascends to the 2nd floor and enters a room with a very long and large black-and-white photo on the wall capturing a street scene from pre-bombed Hiroshima that is followed by a similar curving photo showing the smoldering aftermath. In the center of that room is a large diorama with a map of the city where a looping video simulates the bombing with the sound of the engines heralding the approach. The nose of the B29 appears just before the entire scene explodes into a fireball followed by smoke billowing from the ruins. Along with other patrons I lingered and watched this riveting video several times.

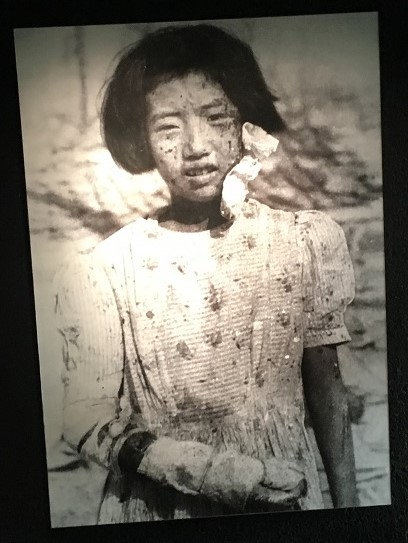

Visitors proceed down a long, darkened hallway where at the end there is an illuminated photo of a bandaged girl. This second section features artifacts left by children killed in the bombing with panels telling us who they were and what they were doing when the blast struck. Images of cute children are juxtaposed with the remnants of lives unlived, an unnerving contextualization that lingers. It is a dark windowless space for contemplation of the unimaginable. There are witnesses’ testimonies interspersed with pieces of twisted metal, tattered clothing, singed school bags, a fragmented Buddha statue, demons’ faces and a child’s tricycle. Large photos of the victims connect these items with individuals, conveying a startling poignancy that eludes the grim statistics. The curator(s) succeeds in capturing the “inhumane nature of nuclear weapons” and promoting the agenda of “No more Hiroshimas.”

|

|

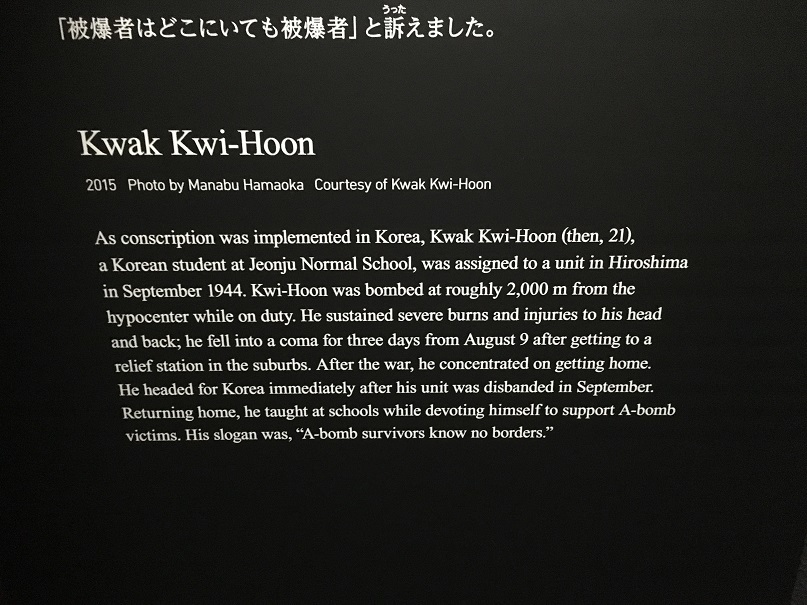

Foreign-born victims of the bombing have been brought into the new narrative through wall panels and big photos on three non-Japanese: an elderly South Korean, a student from Malaysia and a German priest. Yet, in my view, in this space Koreans don’t get their proper due. We learn that nuclear weapons don’t discriminate and that the casualties included, “Tens of thousands of Koreans, Chinese, Taiwanese, as well as Japanese-Americans [who] were living in Hiroshima at the time, including those who had been conscripted or recruited from those areas.” Not untrue, but somewhat misleading since Korean forced laborers were by far the largest foreign-born ethnic group working in Hiroshima’s factories; estimates of their deaths from bombing and radiation range up to 20,000. Thus, placing a plaque in a corner–Away from Home–commemorating all the “destroyed lives” of foreigners in Hiroshima, including American POWs (a handful), German priests (a few), Russian families (three) and students from Asia, is an improvement on the museum’s previous narratives, but an inadequate recognition of the far larger-scale deaths of Koreans. Lumping together such disparate groups whose only commonality was not being Japanese, and whose varied experiences and stories remain largely untold and unappreciated, fails to dignify their humanity in the way the room does so admirably for Japanese casualties.

According to Robert Jacobs, who participated in advisory councils for the 2019 renovation, “several committee members advocated for very direct and specific panels on the Korean hibakusha. They got very serious pushback from several older members who strongly asserted that there were many hibakusha living abroad and we should restrict the panels to them as a collective rather than singling out the Korean hibakusha.”

|

Visitors do encounter Kwak Kwi-Hoon, a Korean student who was conscripted and assigned to work in Hiroshima, who survived with serious injuries and subsequently became an advocate for Korean hibakusha. His slogan “A-bomb survivors know no borders,” confronts the reality that the Japanese government long denied Korean hibakusha the medical care and financial benefits accorded to Japanese hibakusha. Only after the Osaka High Court ruled in 2002 that “survivors are survivors wherever they are” did Japan stop discriminating among hibakusha by providing allowances to overseas survivors beginning in fiscal 2004. However, overseas beneficiaries get less money than hibakusha in Japan receive, an amount that doesn’t fully cover medical treatment. Reacting to this ongoing discrimination, Kwak Kwi-hoon, in an interview, told the media that the government should equalize treatment in line with the court ruling and, “not torment and discriminate against them through prolonged trials.” 9 They are a substantial number of people; as of March 2018, there were 3,123 holders of the card abroad, including 2,241 in South Korea, 667 in the U.S., 95 in Brazil, 31 in Canada and 17 in Taiwan.10

Next in this section, visitors see the eerie shadow of someone etched into stone by the nuclear flash and learn about the black rain that exposed many to high concentrations of radiation. An estimated 60,000-80,000 were killed instantly while the death toll climbed to 140,000 by the end of 1945 as radiation took its grim toll. Large photographs capture the ominous “spots of death” that appeared on the skin of those who had been exposed to high levels of radiation, signaling their imminent death. Some survivors lost all their hair while others were scarred with horrific burns and keloids that remained painful and debilitating reminders of August 6, 1945 over decades to come. And, there was the social stigma of being a hibakusha, powered by fears that the grim reaper was never far off and that any children would inherit a Pandora’s Box of illnesses. We also encounter orphans and elderly survivors all alone, without their disappeared families.

One of the most welcome developments in the new exhibit is the recognition that many survivors suffered from post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD). While Japanese society values gaman-zuyoi (perseverance), embracing uplifting stories of people overcoming adversity against the odds, the reality for many was far less heartening. Many hibakusha suffered from listlessness and an inability to concentrate even after their physical wounds healed. This syndrome was termed buraburabyo (chronic fatigue) and many suffered from recurring bouts of crippling lethargy. Some people found it hard to hold down a regular job. Many were haunted by the suffering of relatives and friends, some who perished slowly and painfully from ghastly wounds, and by the nightmarish scenes of mass death they had witnessed, while others suffered from survivors’ guilt. This aspect of the exhibit underscores how social norms have changed over the decades, as society now shows more compassion to those suffering psychological illnesses, long avoided as an embarrassment. The curators deserve kudos for bringing this aftermath of the atomic bombings into the narrative.

Departing this section, patrons learn about the tragic fate of the bandaged girl we saw at the entrance. She died of leukemia in 1955, a macabre end that crept up quietly on many who imagined they had escaped the Dark Angel. The “living hell on earth” proved a lingering shadow that loomed over survivors trying to put their lives together, making it all the more difficult to do so.

Visitors proceed along a glass-walled corridor, a bright space that takes some adjusting to after emerging from the sepulcher dimness that precedes. The vista encompasses the Peace Park, Memorial Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, reflecting pool, and Flame of Peace with the iconic A-Bomb Dome looming in the distance. In the center of this corridor is a viewpoint silhouette that identifies these prominent landmarks.

|

I was pleasantly surprised that the monument to the Korean victims is also indicated even though it is behind some trees and not visible from the museum windows. Their memorial not only commemorates the A-bomb victims but also the lingering discrimination against their memory.

|

The sad history of this memorial stone is an indelible indictment. In 1970 Korean residents of Japan, zainichi, applied for permission to place a memorial to Korean victims in the Peace Memorial Park, but city authorities refused. They built it anyway and placed it across the road, a glowering monument of reproach. Finally, in 1999, shortly after the 1995 museum renovations that acknowledged Japanese aggression in Asia, city officials found suitable space in the park to relocate the stunning stone sculpture of a large turtle with a tall obelisk rising from its back. It is always festooned with garlands of memorial cranes and bears this inscription: “Toward the end of the war, around 100,000 Koreans were living in Hiroshima as soldiers, civilians working for the army, conscripted workers, mobilized students and ordinary citizens. When the atomic bomb was dropped, the precious lives of around 20,000 Koreans were instantly snuffed out.” Their saga is belatedly acknowledged in this way in the park, although inadequately in the museum, complicating the Japanese victimization narrative while bearing testimony to lingering prejudice and indifference about their fates.

|

The third section of the exhibit focuses on the Manhattan project, particularly the scientific challenges it represented and the geopolitical context for development and use of the bomb. This room has 20 touchscreen panels where visitors can access information on various subjects, an area that attracted many students during my visit, in addition to dioramas, explanatory panels and even miniature models of the atomic bombs-Little Boy and Fat Man-dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

|

This section presents a somewhat biased narrative based on errors of omission and some subtle distortions. It implies that US machinations mattered more than Japanese intransigence in determining when the war ended. It also intimates that American knowledge of Japan’s efforts to seek a negotiated surrender through Soviet mediation based on intercepts of secret cables should have influenced the US end of war strategy more than it did. Perhaps, but there is much to quibble about. One panel lays out the logic of the various options the US considered before deciding on the atomic bombings but provides no analysis of the assumptions and calculations that led to the fateful choice. The exhibit explains in an overly simplistic manner, “The United States believed that ending the war with an atomic bombing would help prevent the Soviet Union from extending its sphere of influence. It would also help justify to the American people the tremendous cost of atomic bomb development.”

The panel on the Potsdam Declaration is fascinating but also somewhat misleading in ways that play to a revisionist view of history. The synopsis of the declaration elides some crucial points, for example asserting that it called for the unconditional surrender of Japan whereas the document actually called for the unconditional surrender of the armed forces, a critical detail that hinted favorably about the fate of the Emperor, the paramount worry for hardliners who rejected unconditional surrender because of the uncertain fate of the Emperor and their martial pride. Moderates such as Foreign Minister Togo Shigenori were inclined to accept the Potsdam terms because they took the hint, wanted to spare their fellow Japanese more unnecessary suffering and worried about growing signs of popular discontent that might threaten the Imperial Household.

In February 1945 the Japanese military leaders conducted a study that determined Japan had no chance to win the war but chose to fight on despite their inability to protect the people from the consequences of the war. That was before the peak of massive US firebombing as well as the atomic bombings.11 The military appeared ready to fight down to the last Japanese. It was also before the Battle of Okinawa and Okinawans still resent being used as sacrificial pawns in a war everyone knew was a lost cause. But the museum doesn’t reflect on the responsibility of Japan’s military or imperial elite, assigning all responsibility to the US. This is not to suggest that the US bears no responsibility for a bombing strategy that took the lives of close to half a million Japanese citizens between March 9 (the date of the first Tokyo raid) and August 15, 1945 (the surrender), but the failure to end the war before the atomic bombings and the Soviet entry into the war was not solely America’s fault. Only so much can be packed into a panel so, understandably, nuanced explanations suffer, but the slant of the narrative is instructive.

One panel clearly mentions that the Japanese triggered the war with its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, but makes no mention there of the wider context of the Sino-Japanese war that had escalated since 1937, and poisoned relations between Tokyo and Washington. Nor is there any reference to the Japanese stationing of air squadrons in southern Indochina in June 1941 in preparation for the planned invasion of Southeast Asia that precipitated the US embargo the following month. This widening of the war to secure resources crucial to victory in China was viewed by American policymakers as threatening because it heralded a Pax Nipponica in Asia detrimental to US interests and because Japan was allied with Germany, raising concerns that some of the resources would be diverted to Hitler’s war machine and thus harm Allied interests.

|

The detailed panels in the next section, on nuclear testing, radiation, disarmament and proliferation, are sobering and discouraging. Their inclusion marks a welcome addition to the museum, ensuring that visitors are introduced to the arc of atomic history from 1945 to the present, thereby reinforcing Hiroshima’s relevance in the 21st century. Jacobs, who advised the curator in charge of this section, confides, “I tried to get the inclusion of multiple test sites, but in the end they put up three pieces about the Marshall Islands, and one about Kazakhstan, and that is because of the death of a Japanese person from the Marshall tests.” (Personal communication July 2019) This casualty resulted from the 1954 Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb test in the Bikini Atoll, the fifth largest nuclear explosion in history that rendered some areas uninhabitable and also exposed the Japanese crew of the Lucky Dragon #5 to high levels of radiation, one of whom died. Beyond inspiring the Godzilla film series, this test was included, according to Jacobs, because it gave “birth to the Japanese antinuclear movement. So, it was a way of only referring to the ‘global’ in so much as it reflected back on the domestic.”

|

The final section of the museum’s permanent exhibits provides some of the most valuable historical context, but by the time visitors make it this far, few spend much time there. Tours are rushing on, time is running out and students’ concentration may be flagging, so during my visit I was the only one delving into the trove of information available in the touchscreen panels. This is a shame because here one can learn a great deal about Hiroshima and its wars.

|

As in the 1995 narrative, Hiroshima is depicted as an important military base and a city fully caught up in the war effort. Several panels elaborate on these themes and implicate Hiroshima in every significant military campaign since the 1895 Sino-Japanese War. One panel titled War, Troops and Civilians refers to the Nanjing Massacre (eschewing the more euphemistic term Nanjing Incident or total denial favored by revisionists) and a damning assertion that “the Chinese sacrifice included soldiers, POWs, civilians and children.” Fascinating details about wartime censorship, mobilization and bamboo spear drills for schoolchildren in preparation for an anticipated invasion, convey the pathos of the era. There is also reference to Japan’s official ‘decisive war’ strategy affirmed in June 1945 to delay surrender in order to inflict greater damage on the US military in hopes that a war-weary America would agree to a negotiated peace.

A clear reference to Koreans as forced labor defies revisionist denialism. Bluntly stated, “many of these Koreans were mobilized for labor service, conscripted to work at Japanese factories and other facilities against their will (forced relocation/ forced labor).” Another file one can access from the touchscreen panels refers to Forced Relocation/Forced Labor. Noting the post-1939 evolution of euphemisms for this mobilization, from “recruitment” and “official job placement” to “conscription” and “mass immigration”, the museum acknowledges that only in the postwar era did it gradually “come to be called ‘forced relocation’ or ‘forced labor’ to emphasize that Koreans were mobilized against their will.” Furthermore, visitors learn that this system was also imposed on Chinese. Another file admits that overseas hibakusha (mainly Koreans) were denied the benefits typically granted to hibakusha in Japan until it became possible in 1980 for them to visit Japan for treatment and, by the dawn of the 21st century, apply for funds to cover treatment wherever they lived.

|

|

|

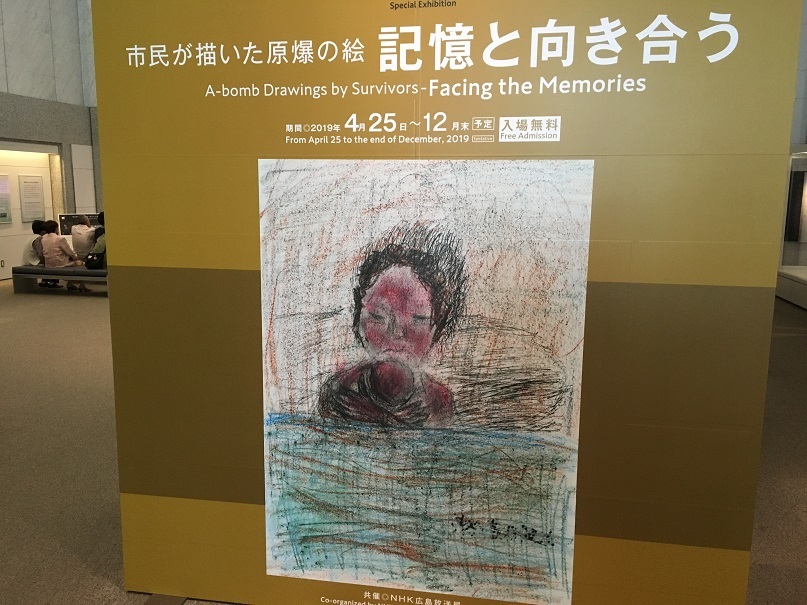

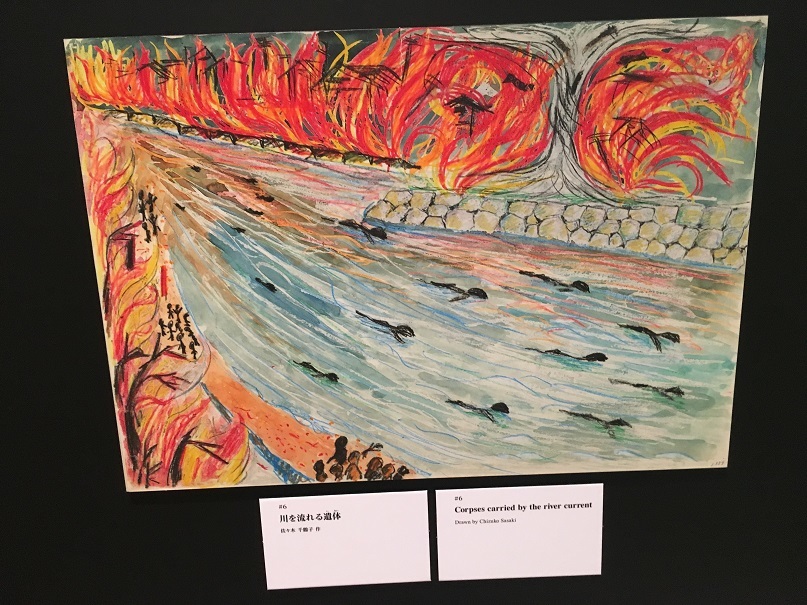

The popular, final temporary exhibit –A-bomb Drawings by Survivors-Facing the Memories- is excellent and worth visiting before it closes in December 2019. The powerful memories on display in these simple images submitted to the local NHK bureau by an army of amateurs show visitors the horrors survivors experienced and remain haunted by. The last stop is the gift shop where messaged t-shirts (‘No Peace, No Life’ is popular), various memorabilia and books (many in English including the Barefoot Gen manga series) are on offer.

|

Conclusion

Start to end my visit took about 2.5 hours, probably longer than most visitors spend, highlighting the concerns of a thirtyish Hiroshima native who shared her critical perspective on the renovated museum. In her view, the 1995 version was preferable and more honest because it confronts visitors at the outset with Japan’s culpability. She doesn’t think that highlighting this aspect in any way justified the atomic bombing, but it informed Japanese visitors, especially students, about an essential context for understanding the Hiroshima experience. In her view, by pushing this context to the end of the tour when time and patience are running out, the museum chose to marginalize it. So, even if some damning information is embedded in the touchscreen panels near the exit, only persistent and dedicated visitors will access it. On my visit, nobody else took the time to do so.

Accessing the critical context depends on visitors digging into what is available whereas the depictions of Japanese suffering are prominently displayed at the outset. Those displays certainly do reinforce the museum’s anti-nuclear weapons agenda, but also play to the comforting victim’s narrative that insidiously exculpates Japan’s wartime leaders. I think in fundamental ways her argument is a valid indictment: issues of responsibility are blurred, shifted or elided unless one discovers the powerful counternarrative at the end subverting that wishful revisionist stance.

Nonetheless, bearing such reservations in mind, I think this is the best of the three versions and don’t agree that the ordering necessarily serves a revisionist amnesia. Some of Japan’s wrongdoing and culpability is acknowledged here, and the new emphasis on the deprivations and impositions of wartime life endured under the militarist martinets elevates this exhibit above the previous iterations. Thus, I grant the curators the benefit of the doubt and offer kudos for managing to include so much that complicates and subverts officially favored narratives even as they are prominently displayed. What visitors can now see is light years better than the contextually blank version I first encountered, while usefully complicating the 1995 version. Although version 3.0 at first seems to genuflect at the altar of revisionism, it ultimately debunks key shibboleths of this reactionary history.

Notes

The museum opened in 1955. In the first major renovation for the fiftieth anniversary in 1995, the bombing was contextualized in terms of Japan’s post-1895 imperial trajectory and the fifteen-year war 1931-45. In the second major renovation, the new exhibits opened in April 2019 after two years of work based on planning that began in 2010. Teams of experts participated in advisory committees under the supervision of museum curators overseeing the new exhibits.

John Dower, War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific. NY: Pantheon, 1987; Eri Hotta, Pan Asianism and Japan’s War 1931-45. NY: Palgrave McMillan, 2007; Yuki Tanaka, Hidden Horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II. 2nd ed. Boulder, CO. Rowman & Littlefield, 2017.

Ienaga Saburo, Japan’s Past, Japan’s Future: One Historian’s Odyssey. Boulder, CO: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000.

From March-March 2018-2019 there were about 430,00 visitors from overseas and 1.51 million Japanese visitors. “Foreign hibakusha speaking out as museum dedicates section to them”, Mainichi, June 18, 2019.

Jeff Kingston, “The Politics of Yasukuni Shrine and War Memory”, in Saaler and Szpilman, eds, The Handbook of Modern Japanese History. Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2018.

Mark Selden, “American Firebombing and Atomic Bombing of Japan in History and Memory”, Asia Pacific Journal, Dec 1, 2016. Vol. 14, Issue 23, number 4.