July 21 2019, 8:01 a.m.

An american organization founded by tech giants Google and IBM is working with a company that is helping China’s authoritarian government conduct mass surveillance against its citizens, The Intercept can reveal.

The OpenPower Foundation — a nonprofit led by Google and IBM executives with the aim of trying to “drive innovation” — has set up a collaboration between IBM, Chinese company Semptian, and U.S. chip manufacturer Xilinx. Together, they have worked to advance a breed of microprocessors that enable computers to analyze vast amounts of data more efficiently.

Shenzhen-based Semptian is using the devices to enhance the capabilities of internet surveillance and censorship technology it provides to human rights-abusing security agencies in China, according to sources and documents. A company employee said that its technology is being used to covertly monitor the internet activity of 200 million people.

Semptian, Google, and Xilinx did not respond to requests for comment. The OpenPower Foundation said in a statement that it “does not become involved, or seek to be informed, about the individual business strategies, goals or activities of its members,” due to antitrust and competition laws. An IBM spokesperson said that his company “has not worked with Semptian on joint technology development,” but declined to answer further questions. A source familiar with Semptian’s operations said that Semptian had worked with IBM through a collaborative cloud platform called SuperVessel, which is maintained by an IBM research unit in China.

Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., vice chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee, told The Intercept that he was alarmed by the revelations. “It’s disturbing to see that China has successfully recruited Western companies and researchers to assist them in their information control efforts,” Warner said.

Anna Bacciarelli, a researcher at Amnesty International, said that the OpenPower Foundation’s decision to work with Semptian raises questions about its adherence to international human rights standards. “All companies have a responsibility to conduct human rights due diligence throughout their operations and supply chains,” Bacciarelli said, “including through partnerships and collaborations.”

Semptian presents itself publicly as a “big data” analysis company that works with internet providers and educational institutes. However, a substantial portion of the Chinese firm’s business is in fact generated through a front company named iNext, which sells the internet surveillance and censorship tools to governments.

iNext operates out of the same offices in China as Semptian, with both companies on the eighth floor of a tower in Shenzhen’s busy Nanshan District. Semptian and iNext also share the same 200 employees and the same founder, Chen Longsen.

After receiving tips from confidential sources about Semptian’s role in mass surveillance, a reporter contacted the company using an assumed name and posing as a potential customer. In response, a Semptian employee sent documents showing that the company — under the guise of iNext — has developed a mass surveillance system named Aegis, which it says can “store and analyze unlimited data.”

Aegis can provide “a full view to the virtual world,” the company claims in the documents, allowing government spies to see “the connections of everyone,” including “location information for everyone in the country.”

The system can also “block certain information [on the] internet from being visited,” censoring content that the government does not want citizens to see, the documents show.

Chinese state security agencies are likely using the technology to target human rights activists.

Aegis equipment has been placed within China’s phone and internet networks, enabling the country’s government to secretly collect people’s email records, phone calls, text messages, cellphone locations, and web browsing histories, according to two sources familiar with Semptian’s work.

Chinese state security agencies are likely using the technology to target human rights activists, pro-democracy advocates, and critics of President Xi Jinping’s regime, said the sources, who spoke on condition of anonymity due to fear of reprisals.

In emails, a Semptian representative stated that the company’s Aegis mass surveillance system was processing huge amounts of personal data across China.

“Aegis is unlimited, we are dealing with thousands Tbps [terabits per second] in China more than 200 million population,” Zhu Wenying, a Semptian employee, wrote in an April message.

There are an estimated 800 million internet users in China, meaning that if Zhu’s figure is accurate, Semptian’s technology is monitoring a quarter of the country’s total online population. The volume of data the company claims its systems are handling — thousands of terabits per second — is staggering: An internet connection that is 1,000 terabits per second could transfer 3.75 million hours of high-definition video every minute.

“There can’t be many systems in the world with that kind of reach and access,” said Joss Wright, a senior research fellow at the University of Oxford’s Internet Institute. It is possible that Semptian inflated its figures, Wright said. However, he added, a system with the capacity to tap into such large quantities of data is technologically feasible. “There are questions about how much processing [of people’s data] goes on,” Wright said, “but by any meaningful definition, this is a vast surveillance effort.”

The two sources familiar with Semptian’s work in China said that the company’s equipment does not vacuum up and store millions of people’s data on a random basis. Instead, the sources said, the equipment has visibility into communications as they pass across phone and internet networks, and it can filter out information associated with particular words, phrases, or people.

In response to a request for a video containing further details about how Aegis works, Zhu agreed to send one, provided that the undercover reporter sign a nondisclosure agreement. The Intercept is publishing a short excerpt of the 16-minute video because of the overwhelming public importance of its content, which shows how millions of people in China are subject to government surveillance. The Intercept removed information that could infringe on individual privacy.

You do not have permission to access this content

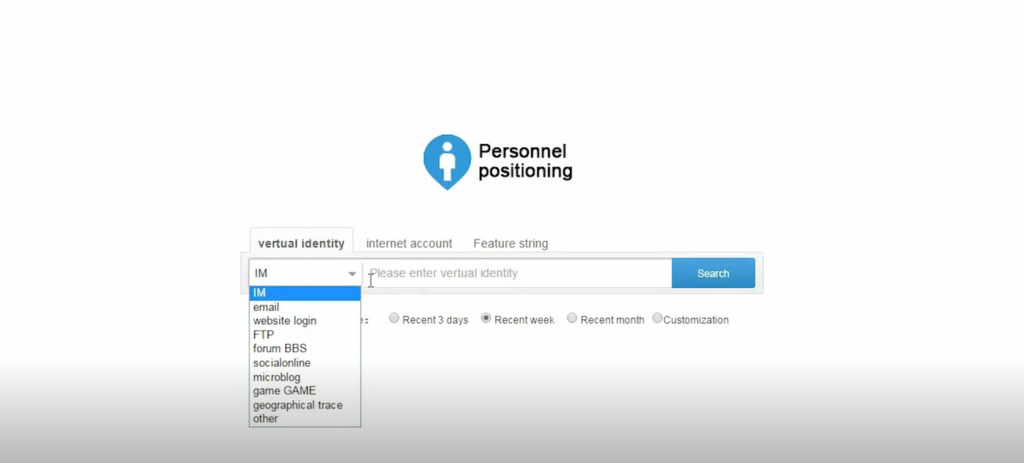

The Semptian video demonstration shows how the Aegis system tracks people’s movements. If a government operative enters a person’s cellphone number, Aegis can show where the device has been over a given period of time: the last three days, the last week, the last month, or longer.

The video displays a map of mainland China and zooms in to electronically follow a person in Shenzhen as they travel through the city, from an airport, through parks and gardens, to a conference center, to a hotel, and past the offices of a pharmaceutical company.

The technology can also allow government users to run searches for a particular instant messenger name, email address, social media account, forum user, blog commenter, or other identifier, like a cellphone IMSI code or a computer MAC address, a unique series of numbers associated with each device.

In many cases, it appears that the system can collect the full content of a communication, such as recorded audio of a phone call or the written body of a text message, not just the metadata, which shows the sender and the recipient of an email, or the phone numbers someone called and when. Whether the system can access the full content of a message likely depends on whether it has been protected with strong encryption.

Zhu, the Semptian employee, wrote in emails that the company could provide governments an Aegis installation with the capacity to monitor the internet activity of 5 million people for a cost of between $1.5 million and $2.5 million. To eavesdrop on other communications, the cost would increase.

“If we add phone calls, SMS, locations,” according to Zhu, “2 to 5 million USD will be added depending on the network.”

In Sept. 2015, Semptian joined the OpenPower Foundation, the U.S.-based nonprofit founded by tech giants Google and IBM. The foundation’s current president is IBM’s Michelle Rankin and its director is Google’s Chris Johnson.

Registered in New Jersey as a “community improvement” organization, the foundation says its aim is to share advances in networking, server, data storage, and processing technology. According to its website, it wants to “enable today’s data centers to rethink their approach to technology,” as well as “drive innovation and offer more choice in the industry.”

Middle East Dictators Buy Spy Tech From Company Linked to IBM and Google

Semptian has benefited from the collaboration with American companies, gaining access to specialized knowledge and new technologies. The Chinese firm boasts on its website that it is “actively working with world-class companies such as IBM and Xilinx”; it claims that it is the only company in the Asia-Pacific region that can provide its customers with new data-processing devices that were developed with the help of these U.S. companies.

Last year, the OpenPower Foundation stated on its website that it was “delighted” that Semptian was working with IBM, Xilinx and other American corporations. The foundation said it was also “working with some great universities and research institutions in China.” In December, OpenPower’s executives organized a summit in Beijing, at the five-star Sheraton Grand Hotel in the city’s Dongcheng District. Semptian representatives were invited to attend and demonstrated to their American counterparts new video analysis technology they have been developing for purposes including “public opinion monitoring,” one source told The Intercept.

It is unclear why the U.S. tech giants have chosen to work with Semptian; the decision may have been taken as part of a broader strategy to establish closer ties with China and gain greater access to the East Asian country’s lucrative marketplace. A spokesperson for the OpenPower Foundation declined to answer questions about the organization’s work with Semptian, saying only that “technology available through the Foundation is general purpose, commercially available worldwide, and does not require a U.S. export license.”

Elsa Kania, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security, a policy think tank, said that in some cases, business partnerships and academic collaborations between U.S. and Chinese companies are important and valuable, “but when it is a company known to be so closely tied to censorship or surveillance, and is deeply complicit in abuses of human rights, then it is very concerning.”

“I would hope that American companies have rigorous processes for ethical review before engaging,” Kania said. “But sometimes it seems like there’s a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,’ policy — it’s profit over ethics.”

Semptian, which was founded in 2003, has been a trusted partner of China’s government for years. The regime has awarded the company “National High-Tech Enterprise” status, meaning that it passed various reviews and audits conducted by the Ministry of Science and Technology. Companies that receive this special status are rewarded with preferential treatment from the government in the form of tax breaks and other support.

In 2011, German newsmagazine Der Spiegel published an article highlighting Semptian’s close relationship with the Chinese state. The company had helped establish aspects of China’s so-called Great Firewall, an internet censorship system that blocks websites the Communist Party deems undesirable, such as those about human rights and democracy. Semptian’s “network control technology is in use in some major Chinese cities,” Spiegel reported at the time.

By 2013, Semptian had begun promoting its products across the world. The company’s representatives traveled to Europe, where they appeared at a security trade fair that was held in a conference hall in the northeast of Paris. At that event, documents show, Semptian offered international government officials in attendance the chance to copy the Chinese internet model by purchasing a “National Firewall,” which the company said could “block undesirable information from [the] internet.”

Just two years later, Semptian’s membership in the OpenPower Foundation was approved, and the company began using American technology to make its surveillance and censorship systems more powerful.

|

See video here. |

The device is one of several spy tools manufactured by a Chinese company called Semptian, which has supplied the equipment to authoritarian governments in the Middle East and North Africa, according to two sources with knowledge of the company’s operations.

It is the size of a small suitcase and can be placed discreetly in the back of a car. When the device is powered up, it begins secretly monitoring hundreds of cellphones in the vicinity, recording people’s private conversations and vacuuming up their text messages.

As The Intercept reported on July 13, Semptian has been using American technology to help build more powerful surveillance and censorship equipment, which it sells to governments under the guise of a front company called iNext.

How U.S. Tech Giants Are Helping to Build China’s Surveillance State

Semptian is collaborating with IBM and leading U.S. chip manufacturer Xilinx to advance a breed of microprocessors that enable computers to analyze vast amounts of data more quickly. The Chinese firm is a member of an American organization called the OpenPower Foundation, which was founded by Google and IBM executives with the aim of trying to “drive innovation.”

Semptian, Google, and Xilinx did not respond to requests for comment. The OpenPower Foundation said in a statement that it “does not become involved, or seek to be informed, about the individual business strategies, goals or activities of its members,” due to antitrust and competition laws. An IBM spokesperson said that his company “has not worked with Semptian on joint technology development,” and refused to answer further questions.

Semptian’s equipment is helping China’s ruling Communist Party regime covertly monitor the internet and cellphone activity of up to 200 million people across the East Asian country, sifting through vast amounts of private data every day.

But the company’s reach extends far beyond China. In recent years, it has been marketing its technologies globally.

After receiving tips from confidential sources about Semptian’s role in mass surveillance, a reporter contacted the company using an assumed name and posing as a potential customer. In emails, a Semptian representative confirmed that the company had provided its surveillance tools to security agencies in the Middle East and North Africa — and said it had fitted a mass surveillance system in an unnamed country, creating a digital dragnet across its entire population.

The mass surveillance system, named Aegis, is designed to monitor phone and internet use. It can “store and analyze unlimited data” and “show the connections of everyone,” according to documents provided by the company.

“We have installed Aegis in other countries [than China] and covered the whole country,” stated Semptian’s Zhu Wenying in an April email. He declined to provide names of the countries where the equipment has been installed, saying it was “highly sensitive, we are under very strict [nondisclosure agreement].”

Similar equipment has been used for years by Western intelligence agencies and police. However, thanks in part to companies like Semptian, the technology is increasingly finding its way into the hands of security forces in undemocratic countries where dissidents are jailed, tortured, and in some cases executed.

“We’ve seen regular and shocking examples of how surveillance is being used by governments around the world to stay in power by targeting activists, journalists, and opposition members,” said Gus Hosein, executive director of London-based human rights group Privacy International. “Industry is selling the whole stack of surveillance capability at the network, service, city, and state levels. Chinese firms appear to be the latest entrants into this competitive market of influence and data exploitation.”

Asked whether there were any countries it would refuse to deal with in the Middle East and North Africa, Zhu wrote that Iran and Syria were the only two places that were off limits. The company was apparently willing to work with other countries in the region — such as Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Morocco, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Sudan, and Egypt — where governments routinely abuse human rights, cracking down on freedom of speech and peaceful protest.

Documents show that Semptian is currently offering governments the opportunity to purchase four different systems: Aegis, Owlet, HawkEye, and Falcon.

Aegis, Semptian’s flagship system, is designed to be installed inside phone and internet networks, where it is used to secretly collect people’s email records, phone calls, text messages, cellphone locations, and web browsing histories. Governments in most countries have the power to legally compel phone and internet providers to install such equipment.

Semptian claims that Aegis offers “a full view to the virtual world,” enabling government spies to see “location information for everyone in the country.” It can also “block certain information [on the] internet from being visited,” censoring content that governments do not want their citizens to see.

The Owlet and Falcon devices are smaller scale; they are portable and focus only on cellphone communications. They are the size of a suitcase and can be operated from a vehicle, for example, or from an apartment overlooking a city square.

When the Owlet device is activated, it begins tapping into cellphone calls and text messages that are being transmitted over the airwaves in the immediate area. Semptian’s documents state that the Owlet has the capacity to monitor 200 different phones at any one time.

“Massive interception is used to intercept voice and SMS around the system within the coverage range,” states a document describing Owlet. It adds that there is an “SMS keyword filtering” feature, suggesting that authorities can target people based on particular phrases or words they mention in their messages.

The device taps into cellphone calls and text messages that are being transmitted over the airwaves.

The Falcon system, unlike Owlet, does not have the capability to eavesdrop on calls or texts. Instead, it is designed to track the location of targeted cellphones over an almost 1-mile radius and can pinpoint them to within 5 meters, similar in function to a device known as a Stingray, used by U.S. law enforcement.

When Falcon is powered up, it will “force all nearby mobile phones and other cellular data devices to connect to it,” and can help government authorities “find out the exact house which the targets [are] hiding in,” according to Semptian’s documents.

Falcon comes equipped with a smaller, pocket-size device that can be used by a government agent to pursue people on foot, tracking down the location of their cellphones to within 1 meter.

The fourth system Semptian sells to governments, HawkEye, is a portable, camera-based platform that incorporates facial recognition technology. It is designed to be placed in any location to create a “temporary surveillance scene,” the company’s documents say.

HawkEye scans people as they walk past the camera and compares images of their faces to photographs contained in “multi-million-level databases” in real time, triggering an alert if a particular suspect is identified.

Zhu, the Semptian employee, wrote that some of these tools had been provided to authorities in the Middle East and North Africa region, known as MENA. “Aegis, Falcon and HawkEye are our new solutions for [law enforcement agency] users,” wrote Zhu. “All the three products have successful stories and some in MENA.”

Elsa Kania, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security, a policy think tank, said that Semptian’s exports appear to fit with a broader trend, which has seen Chinese companies export surveillance and censorship technologies in an effort to tap into new markets while also promoting China ideologically.

“The Chinese Communist Party seeks to bolster and support regimes that are not unlike itself,” Kania said. “It is deeply concerning, because we are seeing rapid diffusion of technologies that, while subject to abuses in democracies, are even more problematic in regimes where there aren’t checks and balances and an open civil society.”

This is slightly revised from a two part article that appeared at The Intercept

on July 11 and 12, 2019