Introduction

The chapter that follows is excerpted from my book Women and China’s Revolutions (Rowman and Littlefield, 2019), which asks: If we place women at the center of our account of China’s last two centuries, how does this change our understanding of what happened? Women and China’s Revolutions takes a close look at the places where the Big History of recognizable events intersects with the daily lives of ordinary people, using gender as its analytic lens. Building on the research of gender studies scholars since the 1970s, it establishes that China’s modern history is not comprehensible without close attention to women’s labor and Woman as a flexible symbol of social problems, national humiliation, and political transformation.

Two themes recur throughout Women and China’s Revolutions. The first theme is the importance of women’s labor, both visible and invisible. The labor of women in domestic and public spaces shaped China’s move from empire to republic to socialist nation to rising capitalist power. Some of that labor was recognized by state authorities or intellectuals, leaving a documentary record that allows us to reconstruct how and why women’s labor was valued. Some of it, however, was not so visible in the historical record. Women’s hidden reproductive labor included not only childbirth, but also feeding and clothing household members, raising and educating children, caring for the elderly, maintaining community ties, and producing handicrafts that generated income for their families. This labor was crucial both to the survival of households and to big state projects that depended upon women to work a double shift—for example, in the Mao era, the labor of women who put in one shift during the day in the collective fields and another at night bent over a spinning wheel or loom.

The second theme of the book is the symbolic work performed by gender itself, work that intersected with women’s lives and interests but was not identical to them. The question of what women should do and be was a constant topic of public debate during China’s transformation. Sometimes Woman was deployed as a symbol of a weakened culture; alternatively, Woman became a sign that China was entering the ranks of modern nations. Sometimes women were decried as ignorant and dependent drags on the national economy, and sometimes they were glorified as mothers who could save the nation or heroines who could hasten the achievement of socialism. Women and China’s Revolutions explores what sort of work the symbol of Woman was doing. What concerns did people express through the language of gender? How did that language work, and why was it so powerful? Under what circumstances did women themselves articulate and act upon expanded possibilities for being a woman?

“The Socialist Construction of Women, 1949-78,” which is Chapter 8 of the book, considers women as objects and agents of state campaigns to end prostitution, establish thoroughgoing marriage reform, and retrain midwives across rural China. With an ambitious plan to develop industry and collectivize agriculture, the PRC Party-state radically rearranged women’s working lives and their social communities in both cities and rural areas. This chapter assesses the interaction of Party-state notions of women’s liberation with social practices in households, schools, and workplaces. It traces the reworking of gender roles in two major state campaigns: the Great Leap Forward (1958-1960), which resulted in a catastrophic famine, and the Cultural Revolution period (1966-1976), in which many young urban women participated in the Red Guard movement and then were sent to live and work in the countryside for an indefinite stay. The chapter also examines how intensified investment in rural health and education, and the consolidation of women’s role in collective agriculture, fundamentally altered the dynamics of rural women’s lives. During the Mao years, Woman as symbol (in the form of actual women labor models and composite figures in propaganda posters) was mainly invoked for her potential as socialist producer, rather than for her role in social reproduction. As the chapter observes, “The Party-state’s symbol of Woman—emancipated, with full political rights, striding forward into the socialist future—had only a distant, if inspiring, relationship to the daily lives and labor of women.”

For full citation of references, see Women and China’s Revolutions (Rowman and Littlefield, 2019).

–Gail Hershatter

When the Chinese Communist Party established the People’s Republic of China in 1949, its members brought with them almost three decades of experience in mobilizing women, mainly under circumstances of political suppression and war. After 1949, women’s labor and Woman as symbol were central to the Party-state vision of socialist modernization. The period of socialist development ran from the establishment of the PRC in 1949 through Mao’s death in 1976 and the beginning of economic reforms in 1978. Many accounts of this period have focused on internecine Party struggles, the sidelining and persecution of intellectuals, the lifelong stigmatizing of adults whose class backgrounds were suspect, the terrible human cost of misguided state economic initiatives, and the upheaval entailed in major political campaigns.1 Without minimizing the importance of those aspects of Chinese socialism, this chapter explores a different set of questions: Did women have a socialist revolution? If so, which women, and when? How did the revolutionary process shape women’s daily lives, and how did women’s labor shape the revolutionary process? Although the Chinese Communist Party guided national policy and the state apparatus throughout this period, it had no unified theory of socialism on which to draw, much less one already tailored to the particular circumstances of China. Socialism was improvised, in part based on the experience of the Soviet Union, but always with attention to local circumstances. The Party itself was riven by frequent arguments about what socialism should look like and how it should be constructed. Most of these arguments were not directly about women’s labor—everyone agreed it was necessary. Nor were they about Woman as symbol—everyone agreed, prematurely, that the basic conditions for women’s liberation had been established successfully by the official recognition that women had equal political rights with men.

The All-China Women’s Federation was established as a national mass organization led by the Party. Building on organizational forms developed in the base areas, it had branches attached to every level of government. It was meant to ensure that women’s interests were represented and that women were informed about their part in national reconstruction. A state-published magazine devoted to women, Women of China (Zhongguo funü), kept women’s contributions and issues visible to a national audience.2 But schisms within the Party about how to develop the economy, and debates after the Sino-Soviet split of 1960 about the role China should take in opening a new road to socialism, affected the lives of women even when gender equality was not explicitly on the agenda.

This chapter begins with three campaigns intended to stabilize families: the Marriage Law campaign, which was conducted in the context of land reform; the campaign to introduce scientific midwifery in rural areas; and the urban campaign against prostitution. The chapter then turns to the mobilization of women and the changing gendered division of labor during urban and rural drives for economic development. It concludes with two iconic campaigns of the Mao years, neither explicitly about gender, which had profound effects on different groups of women. The Great Leap Forward and its ensuing famine reshaped the lives of rural women, and the Cultural Revolution and its movement to send urban youth to the countryside changed the lives of a generation of urban women. Two major themes underlie this chapter. The first is that “women” in the period of socialist construction, as in all previous periods, were not a homogeneous group. Generation, region, ethnicity, and level of education all helped determine which events of Big History most touched women’s lives. But perhaps the most profound divide during the socialist period was that between city and countryside, a gap exacerbated by state socialist policies. In the process of socialist construction, resources flowed out of the countryside to fund the cities—but people moved much less, as an increasingly restrictive household registration (hukou) system kept farmers closely bound to their communities. Farmers worked in collectives, where income fluctuated with the harvest but generally remained low, and their only access to food was in their home communities. Social services, including education and access to health care, improved somewhat in rural areas but remained limited. So did access to manufactured goods such as cloth. Most urban dwellers were paid salaries, had easier access to schools and hospitals, and enjoyed a relatively stable supply of food, cloth, and other daily goods. The urban-rural divide meant that the daily activities and sense of possibilities were different for farming women and city women. This chapter pays attention to those differences.

The second theme is that women’s labor undergirded socialist construction in ways that were not completely recognized. The socialist discourse on labor had little to say about domestic labor, which women and their families saw as women’s responsibility. Even as women took on new tasks outside the home, the constant demands of household tasks structured their days before, during, and after their labor for urban work units or the rural collective. The tasks required of rural women were different and more demanding than those urban women had to perform. But for both, the incessant requirement that they maintain their households was not regarded as an urgent problem to be solved in the socialist present. It was deferred to the communist future, when material abundance and socialized housework would lighten women’s burden. In the meantime, domestic labor performed thriftily and with diligence was visible in public discourse as a sign of women’s accomplishment, but not as an essential—and unremunerated—contribution to the building of socialism. The Party-state’s symbol of Woman—emancipated, with full political rights, striding forward into the socialist future—had only a distant, if inspiring, relationship to the daily lives and labor of women.

Marriage Reform And Land Reform

The Marriage Law of 1950 was written with input from women in the Party leadership.3 The law was not substantially different from earlier versions enacted in the Communist base areas and had elements in common with the Nationalist Civil Code of 1930 as well. It announced the end of the “feudal marriage system” and of the “supremacy of man over woman.”4 It outlawed bigamy, concubinage, child betrothal, interference in widow remarriage, the exaction of money or gifts in conjunction with a marriage agreement, and compelling someone to marry against their will. It established a minimum marriage age of twenty for men and eighteen for women and required registration of marriages with the local government. It permitted divorce when both parties desired it, required mediation and a court decision in contested divorces, forbade a husband to divorce his wife during or immediately after pregnancy, and stipulated that a soldier’s spouse could not obtain a divorce without the soldier’s consent.

By issuing this law, the new national leadership signaled its desire to end marriage practices that had been criticized at least since the May Fourth Movement, as well as its intention to insert the state into marriage, formerly the domain of the family, by issuing marriage certificates. Together with the campaign to redistribute land to poor households, the Marriage Law expressed the Party-state’s determination to end a situation in which richer families monopolized land, wives, and concubines, while poor women were trafficked and poor men hired themselves out as landless laborers who could not afford to marry. The Marriage Law, national in scope, encountered particular difficulties in the complex rural situation of the early 1950s. Inexperienced local village leaders, assisted by Party work teams sent from outside, were preoccupied with the land reform campaign. This involved determining the landholdings and class status of every household in every village and redistributing land and property from landlords and rich peasants to poor peasants.5 The land reform process already involved considerable social conflict and violence, and there is little evidence that local leaders had the capacity or the desire to mount an aggressive campaign to implement the Marriage Law. Existing cases of concubinage, for instance, were left in place unless one of the parties asked for a divorce, although new ones were regarded as bigamy, and prohibited.6

|

Women at Ten Mile Inn village political meeting, late 1940s Source: Photograph by David Crook, courtesy of Isabel Crook. |

However, in some ways the new political environment introduced by the land reform was conducive to marriage reform as well. Young women from the cities attached to land reform work teams spent a great deal of time visiting the women of each household, mobilizing them to attend political meetings and explaining current government policies to them. Under the Agrarian Law, women received an allotment of land just like men, even though in practice all family land was held in common and its use was controlled by the household head.7 Older women were encouraged to “speak bitterness” at meetings accusing the landlords and rich peasants of exploitation.8 Younger women learned to speak and sing in public in support of government policies. These activities enlarged their sense of community and social possibility, and many young women found themselves unwilling to go through with betrothals arranged by their families. Some persuaded their families to break off these engagements (see box 8.1). Girls who had been sold to families as foster daughters-in-law, to be raised by their future in-laws and then married to one of the sons, now often returned to their natal families. In short, the new Marriage Law and the new political environment did prevent some “feudal” marriages from taking place.

|

Feng Gaixia Breaks Off Her Engagement Feng Gaixia, who grew up in southern Shaanxi province, was betrothed by her parents in 1949 at the age of fourteen.

After Liberation, Gaixia became a land reform activist, and by the time she was eighteen she was the head of the township Women’s Association. What she heard about the Party-state’s marriage policy from the land reform team emboldened her to break off her own engagement.

Fortunately for Gaixia, her grandfather sided with her and helped to bring her father around.

Gaixia decided to confront her intended husband directly.

Source: Interview with Feng Gaixia (pseudonym), conducted by Gao Xiaoxian and Gail Hershatter, 1997, excerpted in Gail Hershatter, The Gender of Memory: Rural Women and China’s Collective Past (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 96–98. |

But the stakes were much higher in families that already had paid a bride price and acquired a daughter-in-law to contribute her labor and help carry on the family line. Many young women were not happy in such marriages, and undoubtedly some of them hoped that they could escape conditions of poverty and make a better match. Here was a contradiction: a law intended to stabilize families by improving the chances that poor rural men could make a match was now destabilizing communities by threatening to disrupt such marriages. In rural communities, the Marriage Law was popularly known as the divorce law. In-laws and husbands were arrayed against it, directing violent coercion at women who attempted to exercise their new legal rights.9 In each year from 1950 to 1953, the Ministry of Justice said, seventy to eighty thousand people, most of them women, killed themselves or were killed by family members because of family conflicts.10

The Party-state criticized violence against wives who wanted to divorce. But the top leadership had differences of opinion about how forcefully to push marriage reform, and the Law was not publicized consistently on a national level until a one-month campaign in 1953.11 After an initial period in which divorces were granted if the marriages had been made under one of the categories now forbidden by law, authorities concentrated on mediating, with the aim of maintaining household stability and community harmony. They often talked to village leaders, family members, and neighbors as well as to the unhappy couple, trying to solve marital problems while insisting that couples stay together.12 These attempts sometimes bordered on the absurd. One provincial cadre reported in 1953 that a township head had encouraged a quarrelling couple to improve their relationship by engaging in sexual intercourse. The local official insisted that the woman throw her trousers out the window while he stood outside, but his attempt to foster marital harmony failed. The couple continued quarrelling loudly, and the township head ultimately had to throw the trousers back through the window. In cases like this, the provincial cadre argued, the couple should be permitted to divorce.13 Rural and suburban women who were determined to divorce proved adept at finding sympathetic local officials or judges, sometimes traveling in groups to a location far from their own villages to seek redress. In 1953 alone, more than 1.17 million divorces reached the courts.14

Over the course of the Mao years, marriage practices changed, but on a much slower time line than that demanded by the brief and intense temporality of a state campaign. The establishment of rural schools and the collectivization of agriculture provided spaces in which youths could get to know and develop an interest in one another. It remained customary for matchmakers to have a role in formalizing a match, and for parents to have a decisive say, but it grew less common for women to be married off without their consent. By the 1970s, it was becoming common for newly married couples to separate their households from those of their parents. Companionate marriage gradually became a hope and expectation that many rural young people shared.15

One important feature of rural marriage was not addressed by the Marriage Law: patrilocality, in which daughters moved out of their natal homes at marriage and into the homes of their husbands, usually in a different village. This change at marriage continued to mark the lives of women, who left communities where they were known and socially embedded and entered ones where they were strangers and had to establish themselves.16 The change was not as drastic as suggested by the marriage ritual described in chapter 1, in which water was spilled when a bride departed to indicate that she could never return. In practice, young married women often married close by and returned often to their natal families, maintaining close emotional ties, and in some areas they continued to reside more than half of the time with their parents until they became pregnant.17 It is difficult to imagine how the new PRC state, beleaguered as it was, could possibly have challenged patrilocality as a feature of “feudal” marriage, so embedded was it in rural life. But the failure to take it up had consequences: the persistence of patrilocal marriage has continued to limit women’s access to political power and has generated widespread preference for sons well into the contemporary era, as chapter 9 will explore.

Midwifery

Even as the new state was moving to redistribute land and reconfigure marriage, it began to address a pervasive public health problem: the high number of women and infants who died in childbirth.18 Not since the efforts of the Nanjing Decade had the national government been in a position to address this problem. The campaign to do so, unlike those for land reform and marriage reform, was designed to minimize conflict. In most rural areas, as chapter 5 described, babies were delivered by rural midwives who had no formal training. Some midwives had years of experience and considerable expertise in dealing with breech and other difficult births. But their general use of unsterilized implements to cut the umbilical cord led to high rates of puerperal fever in mothers and tetanus neonatorum in infants. In 1952, the Ministry of Health estimated the infant death rate nationally at 20 percent.19

As early as 1950, the newly constituted Women’s Federation, along with the Ministry of Public Health and the very small number of trained new-style midwives, conducted surveys of childbirth practices in the countryside. This was followed by short-course retraining for older midwives and the recruitment of younger women from the villages to train as new-style midwives. Both were trained in sterile technique. The mortality rate declined considerably because of these measures. Older midwives were not vilified as a remnant of the “old society”—they were valued for the rudimentary health-care delivery network they made possible. Across the years of collectivization, except for some short-lived experiments with birth centers, it remained common for rural women to give birth at home. Midwives, usually local farmers who had received training and were paid by the collectives, attended home births.

The midwifery campaign can be seen as part of a larger state project to introduce the latest in scientific knowledge at the grassroots level and to strengthen families by improving women’s and children’s health. The science behind sterile technique became broadly accepted, although rural women were skeptical about the belief current in the 1950s that it was more scientific for women to give birth lying down rather than squatting. Other scientific knowledge about women and reproduction that circulated in 1950s urban China also looks somewhat dated more than half a century later. State-published books and articles promoted the belief that sexual activity was healthy and normal mainly in the context of marriage and reproduction, and that men’s sexual desire was invariably stronger than women’s, which was seen as mainly responsive in nature.20

Prostitution

When Communist forces moved into Shanghai and other big cities in 1949, they had little experience as urban administrators. The challenges facing them included rampant inflation, refugees and beggars living and dying on the streets, unemployment, and opium trafficking.21 For newly minted CCP urban cadres, the cities’ large number of madams and prostitutes was a sign of this disorder, indicative both of corrupt urban morals and the exploitation of poor women. Eliminating prostitution, like ending opium addiction, was for them intrinsic to establishing a strong modern nation, free of the taint of imperialism and the name that had often been applied to China: “sick man of East Asia.” They announced their intention to eliminate prostitution at the earliest possible opportunity, but in Shanghai and other cities they first had to establish basic political control and urban services. By the time the municipal administration moved to round up madams and prostitutes in late 1951, many women had left the trade to find other urban employment or return to their home villages, which were no longer caught up in civil war.

Still, it was a matter of considerable symbolic import for the new government to round up 501 prostitutes and 324 brothel owners. The owners were sent to prison or labor reform, but the prostitutes were remanded to a Women’s Labor Training Institute where they were confined for medical care, job training, and ideological remolding. Like many other urban dwellers who suddenly found themselves under Communist administration, the women were not convinced that the new authorities were there to liberate them. They feared being deprived of their source of livelihood and uprooted from their social networks. Many had close ties to their madams, whom they addressed as “mother.” Some had heard rumors that they would be distributed to Communist troops, used as minesweepers in the anticipated military campaign to take Taiwan, or drained of blood to supply wounded soldiers. The arrival of health-care workers to draw their blood and test them for syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections did nothing to allay their fears. When the head of the Shanghai civil administration showed up at the Institute to give them a welcoming speech and proclaim their liberation, they greeted him with a chorus of wails and overturned their food trays onto the floor.

Ultimately, however, most of the women resigned themselves to the new order, and some eventually welcomed it. The staff of the Institute spared no effort in treating their sexually transmitted infections with scarce penicillin. They talked to the women about how they had been oppressed and why they should embrace new lives as productive citizens, taught them how to weave towels and produce socks, and attempted to reestablish links with their families in Shanghai or the surrounding countryside. Within several years, all of the incarcerated Shanghai prostitutes were released to families and jobs. Those who were not already married were provided with matchmaking services that paired them with poor urban men seeking wives, or sent them off to state farms in the far northwest to marry current or former army men working there.22 Those who returned to Shanghai neighborhoods were under the supervision of newly established Residents’ Committees, staffed by neighborhood women alert to any sign of recidivism.

Wherever women were sent, the intention was to reinsert them into a functioning household, part of a larger effort to stabilize society after many decades of war. Of course, this process was not as easy as the upbeat stories published in the state-controlled press suggested. When the Shanghai city government reviewed the membership of its Residents’ Committees in 1954–55, for instance, it discovered at least one committee in which women’s mobilization work was being staffed by a madam and a prostitute who was supposedly undergoing reform through labor.23 In Beijing and other cities as well as Shanghai, authorities alternated between treating former prostitutes as victims in need of rescue from the exploitation of the “old society” (the umbrella term for the era before 1949) and suspecting them as disruptive elements who might return to their old ways or otherwise derail the project of revolutionary transformation.24 Nevertheless, in a relatively short time the sex trade, an important economic sector in pre-revolutionary Shanghai and a prominent feature of urban social life in many other cities as well, had become invisible. Here was a clear demonstration that commercial sexual services, and the trafficking, gang ties, courtesan celebrities, and aggressive streetwalkers associated with them, were all signs of exploitation to be discarded with the rest of the semicolonial past.

The attempts to reform marriage, the midwifery campaign, and the campaign to end prostitution all aimed to stabilize family formation and reproduction. The goal was a new society in which men would be able to afford to marry, and husbands and wives would have a say in choosing their partners in order to enhance the potential of a happy, long-lasting marriage. Mothers would be able to give birth to healthy children who survived and enhanced the prosperity of the family and the collective. Women would not be sold by their families and would not sell sex in order to survive. Although acceptance of these measures, particularly the Marriage Law, was far from uniform, the idea of stability was deeply appealing to broad segments of the populace after years of war, banditry, and displacement. A woman’s place in the early years of socialism was in the family—from which she could be called forth and mobilized for socialist production.

Mobilizing Urban Women

Party-state authorities devoted much attention in the first few years of the PRC to establishing an effective presence in workplaces and neighborhoods, and women were crucial participants in both projects.

Party committees were installed in every municipal organization and workplace to guide urban administration and economic production, acting as a sort of shadow government. By 1953, the central government had launched its First Five-Year Plan, a blueprint for economic growth modeled on the Soviet example. Old factories were expanded, and new ones were established.

Most state investment went to heavy industry, a sector that historically had employed few women, and the entry of women into traditionally male jobs—drivers, miners, technicians, engineers—was celebrated in the press.25 Industries where women had predominated before 1949, such as cotton spinning and weaving, expanded as well. Many women were drawn into manufacturing, teaching, cultural production, health care, and urban administration. The national campaign to build a modern socialist economy, and the rising numbers of women in the paid labor force, dovetailed with the theory derived from Friedrich Engels that had become dominant in the Party during the wartime years: participation in paid labor was essential to women’s emancipation.

Until 1958, when it became more difficult to obtain an urban household registration, many men who had worked in cities before 1949 brought their wives from the countryside to join them. The birth rate and the number of surviving children both increased, swelling the urban population. Urban social life was increasingly organized around the danwei, or work unit. Large work units provided housing in apartment blocks, sometimes with communally shared cooking space, and the children of workers often went to schools affiliated with the danwei. Some danwei had canteens, clinics, and child-care facilities. Many goods and services were distributed through the danwei: health care, ration tickets for the purchase of staple goods and bicycles, and tickets for films or other entertainment. Weekly political study sessions also took place in the work unit, and political campaigns were publicized there.26

Not all women lived where they worked, because it was common for housing to be distributed through the husband’s work unit. Many women did piece work or handicraft production in small collective workshops, which paid less than the larger state-owned enterprises and did not supply the full range of welfare benefits.27 Even in state-owned enterprises, although men and women were paid equally when they did the same work, women tended to be tracked into lower-paying job assignments and industries.28 And not all women worked—many middle-aged women, or those with many children at home, did not seek regular paid employment. Some took intermittent odd jobs or were mobilized periodically in hygiene campaigns to pick up trash, dredge canals, and kill insects and vermin.29 The Women’s Federation and its local branches were responsible for mobilizing unemployed women, making them aware of national priorities and incorporating them into state-building projects.

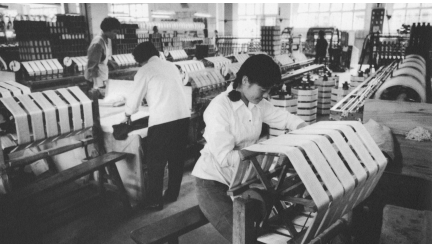

|

Spinning thread, Hangzhou silk mill, 1978 Source: Inge Morath and Arthur Miller, Chinese Encounters (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1979), 214. |

In older neighborhoods outside the larger danwei, the Federation and local governments recruited unemployed or retired women to run the Residents’ Committees, which had their own offices and were responsible for transmitting policy, mediating local disputes, staffing a neighborhood watch, and in general being the eyes and ears of the state. Some officials felt that women who had not circulated much outside the home before 1949 would have fewer problematic social connections and would be politically less complicated to manage than other urban dwellers.30

Government publicity often featured urban women in socially productive roles in industry, science, engineering, administration, and the arts.31 But these were not the only images of women that circulated widely. Women wearing brightly colored dresses, or examining some of the consumer goods newly available to urban working people, also adorned the covers of the Women’s Federation magazine Women of China and other urban publications. Whenever industrial growth slowed, as it did in the mid-1950s, state publications emphasized that the domestic role of women, and their personal attractiveness, were crucial to the health of socialist society.32 Ideal wives were portrayed as interested in political affairs and equal to their husbands, but also willing to sacrifice for them if the men were out contributing to the construction of socialism. No comparable literature was directed at husbands. Marital harmony, when it appeared at all in the press, was primarily a woman’s duty to nurture and maintain.33

Many women enthusiastically embraced what they saw as a new society, free of daily threats to life and safety, in which they were recognized and valued for their work. For one woman, who had been a childhood refugee from the 1942 Henan famine, running a day-care center in the west China city of Xi’an meant providing the next generation of children with the stability she had not experienced as a child. She was willing to work around the clock on that project, even if it meant that several of her own children had to be sent to live for several years with their grandmother because she could not care for them.34 Urban women born in the 1950s recall mothers who put in long hours at their publishing houses or theater companies or factories, sometimes returning home only once or twice a week. When women were sent out to other danwei or to the countryside on the work teams that intermittently were dispatched to do political work throughout the Mao years, they saw their families even less. They spent little time with their children, who were cared for by grandparents or sent to boarding schools at a young age.35

As communities were reconfigured around a common workplace or newly reorganized neighborhood, social life opened well beyond the family, creating new connections as well as irritations. Campaigns to increase production were accompanied by fines for infractions and mistakes in the work. In political meetings, numerous campaigns targeted those who came from suspect class backgrounds or who expressed criticism of the Party leadership. Some women who had been trailblazing lawyers, teachers, and journalists in the 1930s and 1940s, but who were not Communists, found themselves sidelined, their talents unwanted and their motivations put under scrutiny.36 Other women, including the prominent Communist writer Ding Ling, found themselves the casualties of intra-Party struggles and were labeled Rightists in a 1957 campaign and removed from political life except as targets of criticism.37 Many sources of social tension simmered, some of which would manifest themselves during the Cultural Revolution.

Juggling the demands of work, political study, and growing families was a standard feature of urban women’s life in the 1950s and early 1960s, but the double (or triple) day for women was not generally conceptualized as a problem. Even as women’s obligations to engage in socialist construction outside the home were radically reconfigured, government publications continued to promote the importance of a well-run household. The assumption that home was primarily a woman’s responsibility was generally unquestioned.38 A fully committed shift at the workplace followed by a second unremunerated shift at home was a standard feature of urban life for women.39 Domestic tasks—cooking, shopping, cleaning, child rearing—remained time-consuming and expanded with the growing numbers of children. Housing stock did not keep up with the growth in population, and by the 1960s, families were crammed into small living spaces. No longer the underpinning of a dynastic empire or the proving ground of a New Life, the home was now conceptualized as an ancillary enterprise supporting socialist construction—but not appropriate as a woman’s exclusive focus, because such an attitude could be construed as narrow, selfish, and bourgeois.

In spite of these material constraints and the lack of recognition of their unrelenting domestic work, for many urban women the years of early socialism remained a time of expanded horizons and optimism. Those who were workers enjoyed new social recognition as members of the leading class of socialist transformation. And for all urban dwellers, the rising standard of living and improved access to education and health care offered the prospect of an enticing future.

Mobilizing Rural Women

In the countryside, women’s labor was at the heart of the Party’s drive to raise agricultural production. In the early years of the PRC, much of the rural population still had difficulty getting through the growing season with enough to eat. In some areas, the Party-state encouraged and funded projects such as women’s spinning and weaving co-ops. Women pooled their labor, produced cotton yarn and cloth, and sold it on the market to help their families make ends meet. But this support did not last long. Party leaders envisioned socialism as a rapid move in the direction of collective and then state ownership and control of production and marketing. As the state increased control of the purchase and sale of all kinds of goods in 1954, local rural markets shrank, and households lost the ability to generate income by selling the products of women’s labor.40

Soon after the land reform campaign concluded in the early 1950s, Party-state leaders began to promote mutual aid teams in which neighbors shared labor and farming equipment, particularly during the busy seasons.41 Mutual aid was not a significant departure from customary practice before 1949. Many villages comprised networks of male kin and their married-in wives, and it was common for relatives to pool labor in times of need. But this change was not enough to spur a dramatic increase in farm production. The national strategy for industrialization relied on cheap and plentiful farm products to feed the cities, generate some foreign exchange, and provide the factories with raw material. The mutualaid teams were soon supplanted by new ways of organizing labor that began to change women’s daily lives.

First, beginning in 1953, village neighborhoods were organized into lower producers’ cooperatives, where several dozen village households pooled their labor and equipment on a regular basis. The state tightened its control over the purchase of farm products, buying from farmers at relatively low prices so that, in effect, the countryside was subsidizing the food supply and production campaigns of the cities. At the end of the year, after the harvest was sold, rural households were compensated. Most of the proceeds were distributed according to the land, equipment, and livestock they had provided. About 20 percent was distributed according to their labor.

Beginning in late 1955, this arrangement was replaced by advanced producers’ cooperatives. These were bigger groups, sometimes the size of an entire village, divided into work teams. Private ownership of land, so recently distributed to households, was abolished. Each farmer earned a certain number of work points per day for labor. Proceeds were distributed, as before, after the harvest was sold. The collective guaranteed that each household would receive enough grain to support its members, but if the household’s members did not earn enough work points to cover even this basic subsistence, they could borrow from the collective and clear the debt later.42

Mobilizing women was an important piece of this state initiative. Women had long been active in the fields during the sowing and harvest seasons, with regional variations. Now they were encouraged to participate year-round in collective agriculture, where their labor could help to raise productivity in the fields and free up the labor of some male farmers to work in other collective enterprises such as machine repair, flour milling, and irrigation works.

Women labor models attended regional and even national meetings, where they were introduced to the nation’s top leaders. At home, they acted as a live embodiment of agricultural extension techniques, modeling for other women how to grow cotton, ward off insect pests, fertilize the fields, and participate in political campaigns. Often the women themselves were minimally literate and unaccustomed to public speaking, but teams sent by the Women’s Federation helped to identify them, taught them how to sum up what they knew, answered their correspondence, and wrote accounts of their daily activity to publicize beyond their immediate community. Women labor models provided a direct link between policies generated by a faraway state and ordinary village woman.

|

Labor model Cao Zhuxiang growing cotton, 1950s Source: Photo courtesy of Cao Zhuxiang. |

Women labor models were meant to model mobilization, not women’s emancipation. Nevertheless, being a woman labor model was a gendered experience. Both men and women labor models were expected to work hard and create new production techniques, but only women labor models were routinely praised for doing a good job of raising their children, treating the collective’s livestock with maternal concern, and maintaining domestic peace and harmony with their husbands and in-laws. Women labor models had to be above reproach and controversy in their personal lives, not subjects of community gossip. They had to complete domestic tasks and manage the family’s emotional life in a way that enhanced rather than interfered with collective production.43

For all women who came out to work in the fields, mobilization created a profound change in their social lives. Already, the land reform and marriage reform campaigns, as well as winter schools aimed at teaching villagers basic literacy, had drawn women out of their homes to meetings and classes. Initially, the senior members of a household often opposed the efforts to involve younger women because they feared that their daughters might be sexually compromised or their daughters-in-law might be tempted to seek a divorce. In the early 1950s, stories abounded of angry parents and in-laws who had locked up their young women, or barred the door and refused to feed them on their return, or abused them verbally and physically.

Patient persuasion by the work teams overcame some of this resistance. Now, with collectivization, it became absolutely necessary for every able-bodied member of a household to labor in the collective fields and earn work points.44 Under these circumstances, the residual reluctance to let young women out unsupervised quickly evaporated. Unmarried adolescent daughters and young married women spent much of their days working and socializing in the company of their peers—and within range of groups of young men. Across the collective period, village mores about social mixing changed, and the social worlds of village women broadened.

Life in the collectives was far from idyllic for women, however. For one thing, women routinely were paid less than men for their labor, even when they outperformed men at tasks such as topping cotton plants or picking tea. Men generally earned ten work points a day, whereas women earned seven or eight. Each person’s daily working allocation was decided by his or her production team, and the decisions reflected shared assumptions that a woman’s labor was worth less than that of a man, although some reports surfaced about local arguments around this issue. Even as the gendered division of labor changed rapidly, and women took on new tasks, the notion persisted that whatever women did was worth less than what men did.45

|

Two women farmers, Sichuan, 1957 Source: Marc Riboud, The Three Banners of China (New York: Macmillan, 1966), 25. |

In addition, women routinely worked shorter hours than men in the collective fields, but they put in longer days. They came late to the fields after caring for children and preparing the morning meal, and left early to cook at noontime and before dinner. Often they labored in the fields with small children on their backs. This was the rural version of the double day, and because the only labor that was publicly visible and remunerated was labor for work points, women’s earnings were lower than men’s—although still absolutely essential for the welfare of families in rural collectives.

Perhaps the most taxing feature of married women farmers’ lives was the hidden night shift of labor they performed.46 After dinnertime or when evening production planning meetings concluded, women settled down at home to spin thread, weave cloth, and sew clothing and shoes for their ever-increasing numbers of children. Many villages were not electrified until the early 1970s, so this work was conducted well into the night under the light of oil lamps.47

Several factors converged to increase women’s workload in the collective era. First, many of their daytime hours were now spent in the fields, rather than tending directly to household labor. Second, partly because of the end to war and the improvement of midwifery, along with other public-health initiatives, more children now survived infancy. Birth control was not easily accessible or accepted in rural areas, although women sometimes resorted to herbal concoctions and violent physical activities to prevent or end pregnancies.48 These methods of family planning were not reliable, and increasing numbers of children had to be clothed and shod.

Third, machine-made cloth, clothing, and shoes were not widely available in rural areas, and they were expensive enough that even farmers who were issued ration tickets preferred to sell them on the black market and make their clothes at home. At times when state demand for cotton was high and most of the crop was requisitioned for purchase, some of the raw cotton that women used to clothe their families had to be gleaned from second pickings through the cotton bolls.49 Their labor time, too, was scavenged from sleeping hours and from the demands of the workday, as women brought their needlework to nighttime political meetings and to the fields to take up during breaks.

|

Woman takes child to the fields, 1960s Source: Marc Riboud, The Three Banners of China (New York: Macmillan, 1966), 60. |

Older women, already past their childbearing years, also faced new labor demands during the collective era. Those whose physical strength no longer allowed them to earn substantial work points in the field took over child-care tasks from daughters-in-law who went out each day to farm. This household division of labor made it possible for the daughters-inlaw to earn work points, but the child care performed by the older women was not remunerated if it was performed within the household. And older women felt the economic burden of grandchildren in another way as well: a multigenerational household with many children who were too young to earn work points had to stretch its resources to avoid borrowing from the collective. Strained by the demands of these growing families, some grandparents formally separated out their households as accounting units from those of their married sons, even if they continued to live in the same dwelling, so that the younger couple was primarily responsible for providing food for their own children. This gradual weakening of intergenerational co-residence eventually helped to change the nature of rural marriage and perhaps weakened the sense of obligation that grown children felt to their aging parents.

Essential as they were, the clothing women produced and the double day they worked in the collective era did not count as labor. It was neither remunerated nor publicly recognized because it appeared to take place in a separate domain from that of the collective. Focused on the need to mobilize women’s agricultural labor, and supported by the Engelsian belief that in doing so they were contributing to women’s emancipation, Party-state authorities never fully confronted the degree to which women’s invisible labor was underwriting the entire enterprise of rural socialist construction.

Campaign Time and Domestic Time: The Great Leap Forward and The Famine

“Woman-work”—mobilizing women for fieldwork and other collective tasks—was a routine duty carried out at the village level by a local woman who was often the only woman in village leadership, intermittently aided by work teams sent by the Women’s Federation.50 But woman-work burst out of its usual routines with the heightened demand for rural labor during the Great Leap Forward from 1958 to 1960, a time of disruption, experimentation, and ultimately national disaster that left tens of millions dead and the economy badly damaged. The short and frantic period of the Great Leap was also the beginning—and the end—of the Party-state’s only serious attempt to socialize some aspects of women’s household labor in the countryside. With the collapse of the Leap and the devastating famine from 1959 to 1961, that project was abandoned, and domestic labor was returned to the household and social invisibility. Women’s invisible labor, however, was crucial to household survival in the famine years.

Mao launched the Great Leap Forward in 1958, frustrated with China’s pace of development and convinced that social reorganization would unleash the energy of farmers and power an economic breakthrough. Although many in the Party had grave reservations about his strategy, farmers initially were enthusiastic about its promise of multistory houses, electrification, and abundant food. They accepted the vision Mao articulated that several years of unstinting effort would be followed by “a thousand years of Communist happiness.”51

In both city and countryside, production units were amalgamated into large communes that were supposed to provide economies of scale, combining the functions of both production and government. The pace of work in urban factories increased, but the reorganization did not alter most aspects of urban life. The change in the countryside, however, was fundamental. The newly created rural communes could cover an area as big as a county and incorporate as many as several hundred thousand people. Communes were subdivided into production brigades with five thousand or more households, and production teams that might encompass an entire natural village.52

|

Woman worker in Yumen oil fields, 1958 Source: Henri Cartier-Bresson, in Cornell Capa, ed., Behind the Great Wall of China: Photographs from 1870 to the Present (Greenwich, CT: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1972). |

Suddenly, under the administration of the commune, rural people were required to coordinate their daily labor with people dozens of miles away. Many men, and some women, left their home villages for weeks on end to work on ambitious infrastructure projects in irrigation and road building.53 As the men moved out to do this work and took on the project of smelting steel in backyard furnaces—part of the Great Leap effort to expand and decentralize industrial production—villages began to suffer an acute labor shortage. The 1958 harvest season arrived, bringing a bumper crop, but in many areas the possibility that grain would rot in the fields was very real.

In response, women farmers were mobilized to go to the fields in unprecedented numbers, working long days and nights to complete the harvest.54 Beginning in early 1957, the national Women’s Federation had promoted the “three transfers” policy, in which menstruating, pregnant, or lactating women were supposed to be assigned light tasks in nearby locations working in dry fields.55 During the Great Leap, however, the need for women’s labor overrode such precautions. Often women suffered from exhaustion and health problems, including miscarriages and many cases of uterine prolapse from returning to work too quickly after childbirth.56 These were not always taken seriously by local leaders, including many women in charge of woman-work who felt it was important to put production first.57

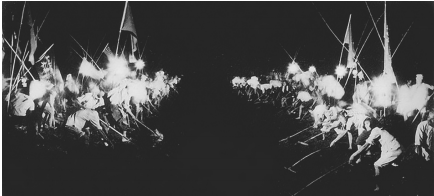

|

Farmers working in the fields at night, Xinyang, Henan, 1959 |

With women’s labor so badly needed in the fields, Party-state authorities paid an unusual amount of attention to lightening women’s domestic burden. The “Five Changes” policy aimed to collectivize meal preparation, clothing production, midwife services, child care, and flour milling. Some of these initiatives, had they been implemented consistently or lasted longer, might have altered rural women’s lives profoundly. For instance, production brigades and teams were encouraged to organize older women to provide child care for women working in the fields and to pay the child minders in work points. But women had to go to the fields regardless of whether child care was available, and tales from this period abound of children who were left tethered to the bed, wandered off and drowned, or were bitten by animals while their mothers worked.

The most ambitious of the Five Changes was the establishment of rural collective dining halls in many production teams, beginning in the hectic summer of 1958. Farmers turned over their food supplies to the production brigade, smashed their kitchen stoves, and handed in their woks and other metal goods to be smelted down for steel. A day’s work was supposed to guarantee all men and women laborers a day’s food in the dining halls, with special provisions for the elderly and children. One of the Great Leap’s most popular pieces of fiction, “Li Shuangshuang,” which was made into a film and rendered as a comic book, centered on the efforts of a voluble and quick-tempered woman to upgrade the food in a dining hall in her village.58

For several months, farmers ate their fill, many for the first time in their lives. Glowing output reports coming in from around the country reassured everyone that the hoped-for Communist prosperity was imminent. But the dining halls soon foundered on the larger problems engendered by the Leap: widespread false reporting of massively inflated productivity by local leaders afraid of being characterized as laggards; excessive government requisitions of grain, in part based on these false reports and in part the result of callous decisions at the top; administrative chaos in huge new structures run by inexperienced cadres; the state decision to repay all debts to the Soviet Union, which in 1960 broke off fraternal relations with China partly over the unorthodox strategy of the Great Leap; and bad weather.

As the food supply in dining halls dwindled, daily meals began to feature thin gruel made of carrot tops, tree leaves, and other marginal sources of nutrition. Women quarreled with the cooks about fair distribution or whether portions could be taken home for sick family members. Villagers hoarded and stole food, fought with one another, and in some areas ate the raw crops directly from the fields before the state could claim them.59 As malnutrition spread and starvation gripped parts of China, the dining halls were disbanded. The project of socializing domestic work receded into the indefinite Communist future. Even if the Party-state had remained committed to the Five Changes and had been able to fund necessary investments in rural areas, so deep was their association with discord and hunger that it is doubtful households ever again would relinquish control over the family food supply.

The famine years from 1959 to 1961 remain one of the most terrible legacies of the attempt to build rural socialism, as well as one of the most catastrophic famines worldwide, still politically controversial more than half a century later.60 The national state, reluctant to admit the scope of the disaster and unable to mount a massive aid effort, left each province to devise its own solutions. In the most severely affected provinces, some farmers—mainly young men—took to the road, looking for itinerant work elsewhere. Older people, married women, and children were less free to move, and control of migration through the household registration system kept most people in place. (The household registration system, along with state controls on the press, meant that many farmers were unaware of the scale of the disaster outside their own locality, and many urban people remained ignorant of the suffering in the countryside.) Human trafficking, particularly a trade in brides from the most severely affected places, was not unknown. But markets for sex workers, concubines, and foster daughters-in-law no longer existed, so one potential option for saving the lives of young women and children, traumatic as it had been in earlier periods, was no longer available.61 Malnourished women suffered high rates of amenorrhea and uterine prolapse in famine-afflicted areas across China. Births plummeted.62 Estimates of the number of deaths across China during this period in excess of what might normally have been expected range from an official estimate of fifteen million to a high of forty-five million.63

Amid this chaos and devastation, women took what measures they could to keep their members alive. They scavenged for food. Those skilled at weaving cloth, embroidering pillows, or making shoes sent their men to carry these products to trade for grain in more remote mountain areas. Mountain villages were poorer than settlements in the plains, but mountainous land had been less intensively collectivized and sometimes still had stores of food. The effective unit of production in many villages shrank to the household, an unauthorized decollectivization that persisted in some areas for several years after the famine abated. The state once again permitted households to cultivate private plots and raise pigs and chickens for their own use, all tasks in which women took the lead.

As harvests began to return to normal levels and cultivation was recollectivized in the early 1960s, the expanded role of women in daily fieldwork was further consolidated. Many men moved to supervisory and technical functions in agriculture, worked in small-scale industries to support agriculture, or became contract factory laborers in towns and cities.64 The labor force in basic-level agriculture was increasingly feminized, while women’s second shift remained untouched.

The Cultural Revolution and The Sent-Down Youth Campaign

In 1966 Mao Zedong, who had been in partial political eclipse since the failure of the Great Leap, staged a political comeback. He sidestepped the Party-state apparatus and called upon the nation’s youth to “bombard the headquarters” and help him combat revisionism, which he characterized as the Party’s turn away from class struggle and the original goals of a Marxist-Leninist revolution. He warned that the Party was now led by “people in authority who were taking the capitalist road” and called for criticism of both the Party leadership and possibly counterrevolutionary attitudes on the part of intellectuals and former elites. His exhortations fell on receptive ears: student activists committed to Maoist ideals, moved by Mao’s call for youth to take the lead in effecting cultural transformation, and also worried about their own future prospects; factory workers dissatisfied with autocratic management backed up by Party authorities; farmers still enraged at how local leadership had permitted their communities to suffer hunger during the Great Leap; and a host of others.

Like the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution had little directly to say about women’s status. Most of the period’s polemics and theorizing had to do with class, centering on questions such as these: could counterrevolutionary class attitudes be passed down from adults to children born after the revolution? Was an old bourgeoisie secretly wielding power in China, or was a new bourgeoisie emerging? The Three Great Differences that Mao said he wanted to narrow were those between mental and manual labor, workers and farmers, and city and countryside. No fourth great difference between men and women existed. Problems of gender inequity were widely regarded as minor, residual, and destined to disappear with time and further economic development.

Gender was downplayed in Party-state directives of the period as well. The Women’s Federation, like many other organizations, was dissolved in 1966, on the grounds that it was permeated with bourgeois ideas and that women’s interests were not distinct from those of men of the same class.65 It was not reconstituted until 1972, and even thereafter it was regarded by many urban women as having nothing to do with them because of its close association with housewives, not working women.66 But like the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution did affect the lives of men and women in gender-differentiated ways, particularly those who were adolescents and young adults at the time. This was the case even when young men and women were involved in similar activities and nothing about gender was explicitly articulated.

The activist phase of the Cultural Revolution ran from 1966 to 1969. During this period, urban middle-school girls and university students joined their male classmates in forming groups of Red Guards. They wrote big-character posters criticizing the leadership of the nation and their own schools. In one notorious and controversial case in the summer of 1966, at a time when the top Party leadership was encouraging teenaged activists to create “great chaos” and local leadership had completely collapsed, Beijing middle-school girls beat the woman vice principal of their school and forced her and other school leaders to carry heavy loads of dirt until she collapsed and died.67 Red Guards, including girls and young women, ransacked the homes of suspected “bad elements,” a group that included intellectuals and former capitalists as well as the Party revisionists who were supposed to be under criticism.68 Students traveled to Beijing, some from great distances, to attend one of the massive rallies in Tian’anmen Square where Chairman Mao appeared to encourage as many as a million students at a time.

Students increasingly became embroiled in the conflicts over which Red Guard faction was more accurately reflecting the intentions of Chairman Mao. By 1967, these disputes had spread to the factories and been fueled by workplace grievances there, resulting in armed conflict and many deaths among the militants, including young women.69 By 1968, the People’s Liberation Army had been sent in to restore order, and the central government inaugurated a vast campaign to “send down” urban youth to the countryside “to learn from the poor and lower-middle peasants.” Shipping young people out of the city also served to quell urban violence and solve a problem of unemployment among urban youths. In 1969, the Party declared that the Cultural Revolution was over, but many of its associated policies, including the sent-down youth program, continued until Mao’s death in 1976 and even beyond. The official Party-state periodization of history now dates the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976, characterizing it as “ten years of chaos.”

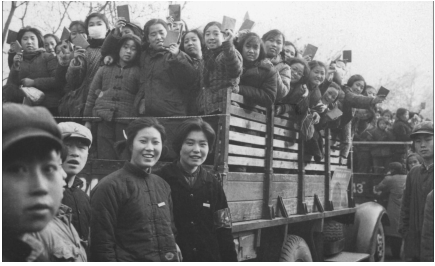

|

Red Guards, 1966 Source: Jean Vincent/AFP/Getty, published in the Guardian, August 25, 1966, reprinted August 25, 2016 |

In Cultural Revolution factional warfare, particularly in the schools, young people formed alliances based mainly on their families’ class labels. The sons and daughters of high cadres stuck together, both before and after their parents came under attack. So did the sons and daughters of intellectuals and bad-class elements, who were not permitted to be Red Guards, and the working-class sons and daughters who had found themselves disadvantaged with respect to the other two groups, in spite of their proletarian background.

Gender was a far less visible organizing axis. Still, it was not absent. Women’s mode of dress signified their class allegiance. Red Guard girl students dressed like male soldiers, with cropped hair, armbands, and wide belts.70 There was a missionizing zeal in their adoption of this military aesthetic: groups of Red Guards seized women pedestrians on city streets in the fall of 1966, cutting their braids, slicing up skirts and formfitting pants, and warning violators of this new dress code not to mimic the fashion habits of the bourgeoisie. When Wang Guangmei, the wife of China’s president, was hauled before a huge political rally to be criticized for her revisionist politics, Red Guards humiliated her by dressing her in a satirically exaggerated version of bourgeois women’s attire: a formfitting dress and a necklace of ping-pong balls.71

The model for political behavior in the early Cultural Revolution was an imagined version of the working-class male. Some young women Red Guards expressed their political enthusiasm by engaging in behavior that was more commonly associated with young men: hectoring, swearing at, and physically abusing suspected class enemies. In later years, when former Red Guards tried to make sense of the atmosphere of those years, one of the main questions they puzzled over was why girls, in particular, had behaved in that way. This puzzlement suggests that in their own assessment, girls and young women had departed more thoroughly from gendered norms of behavior than their male classmates—even though, in fact, beating teachers and abusing neighbors was a departure for young men, too.

Looking back on those years from the vantage point of the post-Mao period, women also recall their sense of adventure, excitement, and sometimes trepidation as they took to the rails and the roads to see Chairman Mao or emulated the CCP’s Long March in treks across China. These travels gave both young men and young women a sense of China’s vastness and provided a degree of autonomy from adult supervision that they would not have encountered in a more normal time. For young women in particular, this period of political activism and travel meant freedom from family and school constraints that young women of previous generations seldom had experienced.

The sense of being unmoored from previous expectations also characterizes women’s memories of being sent down to the countryside. Assigned to state farms or rural production teams, urban young men and women learned new skills, many of them physically taxing. They experienced firsthand the enormous gap in education and living standards between the city and the countryside. Because even the middle-school students among them were better educated than most rural people, many “educated youth,” as they were officially known, were quickly transferred out of fieldwork to accounting and teaching jobs. In young women’s stories, several themes recur: the drudgery of rural life, their exhilaration at learning to ride horses or master agricultural tasks, their sense that rural women of their age operated under much stronger “feudal” constraints than they did, their periodic campaigns against the gendered division of labor and work-point discrepancies, their discovery that farmers often were not at all motivated by revolutionary ideals or class loyalty, their attempts to combat boredom by circulating hoarded copies of novels and language textbooks, and their growing sense of capability and self-reliance. Some also mention the difficulties of navigating adolescence, sexual attraction, sex, and unwanted pregnancy with little guidance from adults or peers, and some talk about instances of sexual assault.72

As young women of urban origin sought to establish themselves in these unfamiliar rural environments, they could draw upon a few propaganda slogans that were addressed to women in particular. One was an enthusiastic endorsement that had first appeared in the People’s Daily in 1956, to the effect that “women can hold up half the sky.”73 (It is usually translated into English as “women hold up half the sky,” making it an accomplished fact rather than a statement of potential. It also has been pointed out by many observers in China and beyond that Chinese women who work a double day may have been holding up more than half of the sky.) Another was an offhand statement Mao apparently made while swimming past a group of young women swimmers in 1964: “The times have changed; men and women are the same. Whatever men comrades can do, women comrades can do too.” His casual observation was reproduced nationally, becoming a standard pronouncement on the state of women’s emancipation: mission accomplished. Here the standard of achievement was male—no one was suggesting that men comrades take equal responsibility for housework or children—but this statement did circulate widely in the Chinese press as an encouragement that women could, and should, contribute to the revolution equally with men.74

A third way in which the state recognized the potential of women was in the approving coverage given to the Iron Girls75 (see box 8.2). They were a group of young rural women in the Dazhai production brigade in north China’s Shanxi Province who worked tirelessly alongside men to rescue the crops from a 1963 flood. Dazhai later became a national model for agriculture, and across the country Iron Girl Brigades were formed. They performed heroic tasks—including repair of high-voltage wires— that women had not attempted previously. Iron Girl Brigades were comprised largely of unmarried women, thus sidestepping the problem of the multiplying demands on women’s time after marriage. In the late 1970s, as China entered the post-Mao reform era, the Iron Girls would become a target for satire and proof that in expecting women to perform the same work as men, the Mao era had violated a “natural” gendered division of labor (see chapter 9).

Finally, women of the Cultural Revolution era could see heroic behavior modeled for them in the eight model operas (and several ballets) created under the sponsorship of Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, whose political power reached a zenith during the Cultural Revolution.76 These productions were almost invariably set in the pre-1949 era, and in most of them one or more of the main characters were women. The plots usually centered on struggle against cartoonishly cruel Japanese invaders or Chinese class enemies. The heroine of The White-Haired Girl, for instance, got her white hair when she retreated to a cave after she was seized from her family and sexually assaulted by a landlord, emerging later under the protection of the Eighth Route Army to denounce her tormentor. Red Detachment of Women was based on the experiences of a unit of women soldiers organized by the Red Army in the early 1930s.

|

A Sent-Down Youth in the Great Northern Wilderness: Two Vignettes Most of us did not feel inferior to men in any way at all. Whatever job they could do, we could do too. In fact, we always did it better. Cutting soybean was probably the most physically demanding work on the farm. We did it only when the fields were drenched with rain and the machines had to stay out. Trudging through mud up to a foot deep, small sickles in our hands, we cut soybeans on ridges that were over a mile long. . . . By the day’s end, those who carried off the palm were always some “iron girls.” At first, the men tried to compete with us. After a while they gave up the attempt and pretended that they did not care. Nobody could beat Old Feng, a student from Shanghai. The men nicknamed her “rubber back,” because she never stopped to stretch her back no matter how long the ridge was. Her willpower was incredible! After her, there were Huar [a local young woman] and several other formidable “iron girls.” Who ever heard of “iron boys” in those years anywhere? In China only “iron girls” created miracles and were admired by all.

A “gigantic counterrevolutionary incident” broke out in Hulin county. Overnight, almost every house in the region was searched and who knows how many poor peasants were implicated. In our village, some fifteen were arrested. My friend Huar and her mother, Ji Daniang, were among them. Their crime was sticking needles into Chairman Mao’s face and body. In fact, they did this unintentionally, for in those days Chairman Mao’s pictures were all over the newspaper the villagers had always used for wallpaper. So after the women sewed, if they stuck the needles in the wall at the wrong place, poor peasants became active counterrevolutionaries and were shut up in the cow shed for months. After Huar’s arrest, occasionally I saw her from a distance. Neither of us dared to speak to the other. . . . Her face, hands, and clothes were extremely dirty and her hair was a big pancake, filled with lice. As a punishment, the “criminals” were not allowed to wash themselves or comb their hair when they were detained. Source: Rae Yang, Spider Eaters: A Memoir (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 178, 242–43. |

In many of these productions, the awakening political consciousness of the women was guided by male Party secretaries. They modeled correct behavior and offered gentle but stern guidance on what the revolution required, discouraging the women from sudden outbursts and quests for personal vengeance.77 The message was that women, too, could be revolutionaries—if they could control their emotions and properly channel their energies under the guidance of a politically experienced man. No cultural productions during the Cultural Revolution were set in the present or addressed inequalities that persisted under socialism. The main message they imparted to women was not a new one: class divisions are fundamental, the roots of women’s oppression are found in class oppression, the road to emancipation is to work alongside men to make revolution and build socialism.

Even in a situation where the state paid little attention to analyzing or ameliorating gender inequality, however, the lives of rural women improved during the 1970s. Cultural Revolution initiatives to improve education in the countryside, and to deploy minimally trained “barefoot doctors” to broaden the scope of health-care delivery, benefited women. So did the slow spread of rural electrification and the absence of further catastrophic experiments such as the Great Leap Forward. Collective agriculture and small-scale industry managed to keep pace with population growth during this period, a significant achievement. Women earned incomes in the fields and small rural factories. Courtship practices continued to evolve in directions that gave young women more say in picking a mate. It continued to become more common for young couples to establish their own households at marriage, with young married women less constrained by their husbands’ parents. The most profound improvements in rural women’s lives were not produced by the utopianism of the Great Leap vision or the heightened politicization of the Cultural Revolution, but rather by the incremental improvement in productivity and stability at the grassroots level in rural communities.

In 1974, as Mao Zedong’s health deteriorated and factions in the top Party leadership jockeyed for control, Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, sponsored a campaign to “criticize Lin Biao and Confucius.”78 Lin Biao was a former close comrade of Mao’s, once designated as his successor, who had died in a mysterious plane crash in 1971. Confucius, the sage of antiquity who had already come under serious criticism in the May Fourth Movement of 1919, was widely seen as a proxy figure for Premier Zhou Enlai, who was regarded by Jiang Qing as an enemy and an impediment to her ambition for more political power.

This campaign rooted in intra-Party struggle did more to highlight persistent gender inequality than any other political initiative of the “ten years of chaos.” In the course of criticizing Confucius, Party commentators devoted substantial time to the age and gender hierarchies that were embedded in classical Chinese political thought and that persisted in much daily social practice. The campaign raised issues about equal work points, bride prices, the need for collectivized child care and sewing groups, the duty of men to participate in domestic work, and even the possibility of matrilocal marriage.

But this campaign, so closely associated with Jiang Qing, soon foundered. In 1976, Jiang was arrested after Mao’s death and put on trial for, among other things, promoting the Cultural Revolution and seizing the opportunity to take revenge on old colleagues in the film industry and the Party whom she felt had opposed her in the past. She was eventually tried, convicted, and held in confinement until her death by suicide in 1991.

The criticisms leveled at Jiang Qing in popular commentary were profoundly gendered, often invoking a saying from imperial times that when a woman seized political power, chaos would result. She was sometimes depicted wearing an imperial crown, or else as a woman’s body divided down the middle—one side portrayed in revolutionary army uniform, a style she helped make popular, and the other side garbed in frilly dresses and high heels. The division was meant to signify hypocrisy, discrediting both halves—the woman who tried to seize power like a military man, and the woman who secretly fancied the life of the bourgeoisie while carrying on a violent campaign against people she castigated as bourgeois. Her political concerns were denounced as purely personal, and her assertion at trial that she had acted as “Chairman Mao’s dog. I bit whomever he asked me to bite” was widely derided.

The downfall of Jiang Qing was accompanied by a popular rejection of Cultural Revolution models for womanly behavior—militant, active, striving to be as good as a man in a man’s domain. An ensemble of mobilizations, slogans, and cultural expressions had been directed at women during the Mao years, encouraging them to be active outside the domestic realm and to understand themselves as equal to men. This discourse was state-initiated, instrumental in its approach to women, and insufficient in its recognition of women’s labor and of newly generated inequalities. It was, however, a powerful formulation that shaped the self-perceptions and sense of possibility of many women who were born and came of age in the Mao years. As girls and young women, they did not see gender as an axis of fundamental inequality, difference, or social concern.79

The repudiation of the Maoist approach to social transformation intensified during the late 1970s. As the economic reforms began to take shape, the heroic women figures that graced Cultural Revolution posters were replaced by a more complicated, multi-vocal, and contradictory approach to gender.

Notes