Abstract: President Donald Trump and Chairman Kim Jong Un met in Hanoi only to part ways abruptly without producing an agreement. Their failure stems, I argue, not from the difference between Trump’s “big deal” and Kim’s “small deal,” but from the incompatibility in their conceptions of the future of the Korean peninsula as well as a common lack of a vision for Northeast Asia. In its zeal to compel the North to disarm, the Trump team conditioned its lifting of UN sanctions on the North’s disarmament of WMDs, not just nuclear weapons. But the Kim team was so singularly focused on enticing Trump to accept a deal that it put on the table what it thought was a big concession, only to be called upon for more. South Korea now has a critical role to play to bring the two parties together to a broader vision for a denuclearized peninsula that is anchored to a more peaceful Northeast Asia.

Keywords: Donald Trump, Kim Jong Un, US-DPRK Summit, denuclearization, peace regime, public diplomacy

The Hanoi summit was a critical turning point in US-DPRK relations. After their first summit that issued a groundbreaking joint statement in June 2018 in Singapore, President Trump and Chairman Kim met in February 2019 without reaching an agreement. As the Singapore summit raised new hopes that the state of war between the US and DPRK would be finally replaced with a peaceful relationship, so the Hanoi summit dashed those hopes. It also had a chilling effect on the jubilation with which the Koreans were building peace and prosperity on the peninsula according to the 2018 Panmunjom Declaration by Moon Jae-In and Kim Jong Un. As the North’s recent military exercise portends, the failure in Hanoi may be followed by a breakdown of the peace process that has been unfolding over Korea since the beginning of 2018, further dimming the prospect of denuclearizing the peninsula. Now is all the more critical to reflect on the Hanoi failure so that the breakdown may be forestalled and the peace/denuclearization process revived.

|

Why is it that the Hanoi summit failed to produce any tangible outcome, after the Singapore summit offered many promises? If President Trump and Chairman Kim agreed in Singapore to normalize the relationship between their countries, build a peace regime on Korea, denuclearize the Korean peninsula, and recover POW/MIA remains in June 2018, they have since made little progress on these agreements except the last. Why? What are the prospects that the leaders will deliver on their promises of normalization, peace and denuclearization? What steps can be taken by the two governments and others, including American citizens, to encourage the two leaders to return to the diplomatic track? I address these questions through the following four points.

- The Hanoi summit ended without producing any agreement because the Trump Team and the Kim Team hold fundamentally different conceptions of the future of the Korean peninsula and both lack a vision for Northeast Asia or the Indo-Pacific.

- The Trump Team offers a tit for tat offer in which it calls on the North to trade its WMD (Weapons of Mass Destruction) programs for a brighter economic prospect because it perceives Chairman Kim’s focus on economic development as an opportunity to rid the North of the WMD programs, but its offer is grounded on a misconception about Kim’s priorities.

- The Kim Team resorts to GRIT (Graduated Reciprocation in Tension Reduction) in which it offers initial concessions in the hope that—or to see if—the Trump Team is serious about implementing the commitments made in the Singapore summit not only to secure denuclearization of the North but also to establish a new US-DPRK relationship and a peace regime for Korea. However, its approach is misguided in that it seeks to normalize its relationship with the U.S. solely on the basis of its negotiations with Trump.

- In order to help the two teams break the stalemate and move toward the denuclearized peninsula, South Korea has an indispensable role to play in terms of building a peace regime not only in Korea but throughout Northeast Asia and increasing the level of transparency on the peninsula.

Two Tales of a City or a Tale of Two Cities?

To the surprise of all and dismay of many the second DPRK-US summit in Hanoi failed to produce even a joint statement that included their points of agreement. That surprise was followed by confusion over what exactly transpired in Hanoi and why the summit failed as two conflicting versions of the event soon circulated. On the one hand, American officials, including National Security Advisor John Bolton, suggested that the North Koreans demanded a lifting of all sanctions in return for a partial shutdown of their nuclear weapons complex in Yongbyon. North Korean officials, including Minister of Foreign Affairs Ri Yong Ho, by contrast, claimed that they offered to completely dismantle the Yongbyon complex in its entirety and asked in return a partial lifting of sanctions. While the truth likely lies somewhere in between these two extreme versions, the two tales of the Hanoi summit confounded observers. They wondered why the two parties failed to meet in the middle as in most bargains. Why could the two parties not agree to either a limited lifting of sanctions in exchange for a partial disarmament or a larger reward for a complete nuclear disarmament or even a roadmap for a comprehensive solution?

I submit that they could not reach an agreement because they held fundamentally different conceptions of the future of the Korean peninsula and offered incompatible approaches to solve the problem. The Americans came to Hanoi seeing North Korea’s WMDs as the central problem and tried to get the Kim Team to agree to comprehensive disarmament of his nuclear and biochemical arsenal. The North Koreans, having serious questions about the Trump administration’s willingness to implement the Singapore commitments, sought to entice it to agree to an initial confidence building measure as a first step toward a comprehensive agreement. Their conceptions of the problem overlapped little; and their approaches diverged.

The Americans would not settle for a partial dismantlement of the North’s nuclear programs because they mistrusted the North Koreans. They in fact demanded much more than the North’s denuclearization by calling for, among other things, “fully dismantling North Korea’s nuclear infrastructure, chemical and biological warfare programme and related dual-use capabilities; and ballistic missiles, launchers, and associated facilities.”2 Not only did they expand the list of demands, but they also made it clear that the lifting of sanctions would be conditioned on the completion of their demands. They argued that if they relaxed any of the sanctions before the North completely dismantled its nuclear program and in fact all weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programs, that would “allow the attended [sic] benefits to flow in a manner that in some cases might directly subsidize the ongoing development of weapons of mass destruction in nondisclosed or noncommitted parts of the weapons program,” as Stephen Biegun revealed after the summit.3 It’s all or nothing, according to the Trump team, because a compromise runs the risk of increasing the North’s WMD capabilities and thus its security threats to the U.S. and the world. The Americans could not trust the North that a partial lifting of humanitarian or civilian sanctions would not lead to the strengthening of its weapons programs. So they insisted on a comprehensive settlement in which the North would completely dismantle its weapons of mass destruction and the US would then reciprocate by lifting the sanctions. Given their logic, they concluded that if the North would not agree to the “all”—that it would dismantle not only all its nuclear weapons and missiles but also biological and chemical weapons and their production capabilities—the only possible deal was “nothing.”

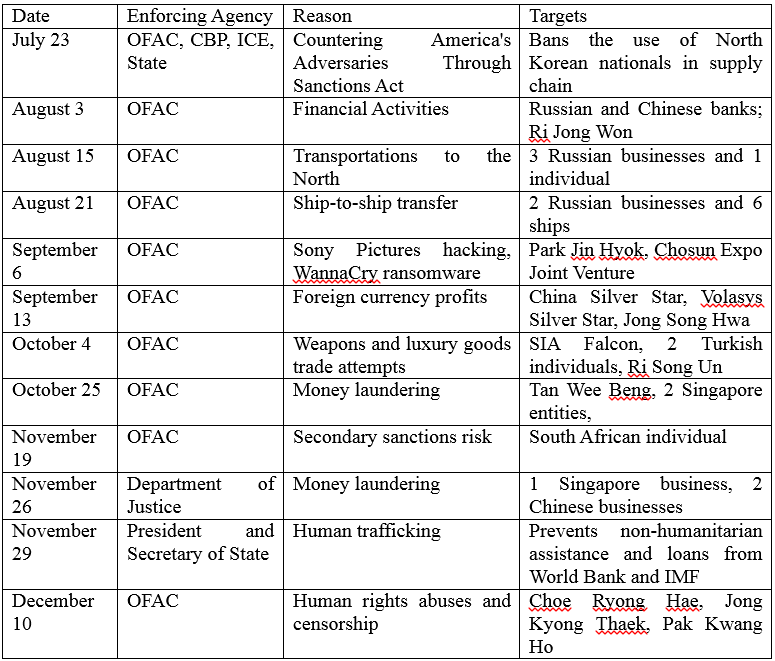

The North Koreans, for their part, could not make a deal in Hanoi because they did not trust the Trump team. Coming into the Hanoi meeting, they had demanded that the sanctions must be lifted because they had halted all nuclear and missile tests since the end of 2017, as the relevant UN resolutions called for. Moreover, they took steps towards denuclearization by closing down the Pungyeri nuclear test site and starting to disassemble the missile test facility in Tongchangri.4 And yet the Trump administration had added twelve more sanctions within 6 months since the 2018 Singapore summit, as Table 1 shows. The flurry of new sanctions stood in contrast with the fact that it had imposed only two sanctions in the first half of the year prior to the summit, raising questions concerning how committed the US was to implementing the Singapore agreement to normalize the relationship.5 North Korea was furthermore slapped with an additional demand that it not only denuclearize but also close down all WMD programs, in return for a promised land of economic prosperity. So if the Trump team refused to take any concrete measures before North Korea completed the denuclearization and disarmament, they could not trust that it was seriously committed to implementing the Hanoi agreement or any future ones. Hence North Korea proposed in Hanoi what amounted to a confidence-building measure: a verifiable dismantling of the Yongbyon nuclear complex in return for a verifiable lifting of some UN sanctions.6 When the Trump team rejected the proposal, their mistrust only grew.

The Trump and the Kim teams each identified the other party as the problem, and proposed the solutions that were inherently incompatible. They stood on no common ground in Hanoi.

|

List of U.S. Unilateral Sanctions against North Korea since the Singapore Summit (2018) OFAC: Office of Foreign Assets Control, Department of Treasury CBP: Customs and Border Protection, Department of Homeland Security ICE: Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Department of Homeland Security (Sources: Assembled from various news sources and 2018 OFAC Recent Actions, U.S. Department of Treasury, Available here.) |

Tit for Tat, and Misunderstanding North Korea

The Trump Team is applying maximum pressure on the North Koreans in order to achieve its priority objective: North Korea denuclearization (by which it refers to the dismantling of all of its WMD). It is offering one big tit for tat: give up all WMD and you “can have a prospect of a very, very, bright economic future.”7 And its tactic is based on the understanding that Kim has set his eyes on the economic development of his country and is willing to trade his weapons of mass destruction for economic benefits. Even such a hardliner as Bolton, according to a New Yorker report, “argued that Kim… was so eager to revitalize the economy that perhaps he could be persuaded to give up his weapons.”8 The Trump Team believes that withholding the economic resources Kim desires maximizes the cost of keeping the weapons programs and hurts him most. It interprets the North Koreans’ demand to lift sanctions—as well as Kim’s travel to Hanoi—as vindication of its Maximum Pressure tactic.9 Therefore, American Tit will only follow North Korean Tat, according to its logic.

This is a serious misunderstanding, one shared not only by members of the Trump Team but also by many in South Korea’s Moon government. That Pyongyang is not pinning its economic hopes on the prospect of an influx of foreign direct investments and international trade can be discerned in the central government’s budget. According to the spending and the budget reported at the annual Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA) meeting, the government expects to draw 85.7% of its income from internal transactions and state enterprises’ profits and lists the other income sources in the order of cooperatives, real estate rental, social security, property sales, other income, and trade. While it represents a change that trade is listed as a source of income, its significance can be inferred from the fact that it is listed even after “other income.” Furthermore, the SPA expects the income from trade to grow by 1.6%, much lower than the 3.7% of national income growth in 2019.10 In other words, the North Korean government grounds its economic plan on the expectation that trade growth will trail behind domestic growth, as it did in the previous year when it made a public transition from the “simultaneous development” policy to the economic development initiative. In contrast, its income from trade grew faster than total income during the years when it was pursuing “simultaneous development.” Its emphasis on domestic growth is reinforced with political campaigns of 자력갱생 (自力更生) that have since last year been growing in intensity.11 While these indicators do not add up to a turn toward autarky—Kim has in fact taken various steps to engage outside economy more seriously, as I argued elsewhere12—they suggest that he is not so desperate for foreign trade and investment as to exchange the nuclear weapons for them. Kim prioritizes economic development, yet is taking a path different from Beijing’s or Hanoi’s.

It is true that the North Korean leadership under Kim Jung Un made a decision in 2018 to shift its national priority from simultaneously developing nuclear weapons and the economy to prioritizing economic development, but its decision needs to be understood within a larger context.13 Common sense suggests that a state prioritizes its survival before anything else. North Korea is no different in this regard. It considers its nuclear weapons and WMDs first and foremost a tool of national security that supports its survival. Given that it has faced military devastation and nuclear threats from the United States since 1950, it is no surprise that the North considers its nuclear weapons as a deterrent.14 Its offer to denuclearize is predicated on the neutralization of nuclear threats from the U.S., and since the early 1990s it has agreed only to the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula—never to denuclearization of North Korea alone. Hence the clause on “no nuclear weapons and no nuclear threats on the Korean Peninsula,” included in the Pyongyang Joint Declaration by Kim Jong Un and Moon Jae In of September 19, 2018, reiterates Kim’s strategic objective as well as his willingness to commit to the North’s denuclearization.15 Denuclearization is, from the North Koreans’ perspective, a deal to trade nuclear weapons for nuclear security, not security for economy.

Furthermore, since the end of the Cold War the North Korean state has shown remarkable consistency in seeking to normalize its relationship with the U.S. In 1992, after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Kim Il Sung made an offer to open diplomatic relations with Washington by having Kim Yong Sun meet with American officials and the likes of Henry Kissinger.16 Kim Jong Il repeated the same initiative during his rule, as he confided to Kim Dae-Jung during the first inter-Korean summit in 2000.17 The agreements, concluded with Washington and Seoul during his rule, included the normalization of the US-DPRK relationship as one of the key clauses.18 Kim Jong Un is continuing the tradition left by his predecessors, as reflected in the first clause of the Singapore Joint Statement that commits the U.S. and the DPRK “to establish new U.S.-DPRK relations in accordance with the desire of the peoples of the two countries for peace and prosperity.” That was portended by the “important statement” issued by the National Defense Commission of the DPRK in 2013 that proposed a high-level meeting with U.S. authorities.19 We can speculate as to why. First, Kissingerian balance of power politics, as conceived by the North Korean leaders, would dictate such an orientation in the post-Cold War Northeast Asia.20 Second, North Korea’s belief in Juche ideology and independent foreign policy also would compel it to look for a superpower that could help counterbalance a new superpower across the border. But the most immediate cause is likely security: the termination of the war and the normalization of the relationship with the U.S. will improve, although not guarantee, its security more than anything else.

The first two Kims failed to achieve the goal of a breakthrough with the US because their country was widely viewed as likely to follow the fate of the Soviet Union and its Eastern European allies. Having made progress in turning around the economy, the third Kim is now using the prospect of giving up his nuclear weapons programs as a tool to achieve the goal that the North has pursued for almost thirty years.21 He has at least thus far shown interest in trading his nuclear weapons programs for corresponding goodwill measures as part of the normalization process. But if this fails, he will fall back on his nuclear deterrent. So the Kim Team is not so much engaged in negotiations to trade nuclear weapons for economic growth as it is seeking to use diplomacy to achieve an end to the Korean War and normalization of relations with the US. It has shown willingness to give up its nuclear facilities as evidence of its seriousness about normalization; and it demands “corresponding measures” from the Trump Team that would substantiate its interest in normalization.

However, the Trump Team at Hanoi refused to take any steps toward accommodation until the North Koreans completed denuclearization and disarmament because it mistakenly believed that the North Koreans were interested in trading their weapons for economic benefits, a course that would leave them vulnerable to military attack. The Trump Team’s—and others’—misunderstanding is central to the breakdown of negotiations.

GRIT and a Misunderstanding of the U.S.

The North Koreans seem to be pinning all their hope on Trump. Even if they may be the only group of people on earth to do so, they have a logic of their own. Because the U.S. has been at war with the North for almost seventy years, most of its officials, from a North Korean perspective, have been trained or charged to implement the war plan. Many Washington pundits also view the North as an enemy. The “Washington Rule,” as Bacevich argues, would operate in a way that perpetuates the war with the North.22 President Trump, in signaling his willingness to talk with North Korea, in contrast to Obama, looks like an exception with whom the Kim Team could work to normalize the relationship. It seized on what it probably viewed as a rare opportunity to realize one of the North’s long-term strategic objectives. It is after all President Trump who agreed in Singapore to normalize the relationship, build a peace regime, and denuclearize the Korean peninsula. In preparing to come to Hanoi, the Kim Team was keen on seeing the US take concrete implementation measures as tangible evidence of his commitment.

The North Koreans had taken actions to dismantle the Pungyeri nuclear test site and the missile site, that they believed would send a signal that they were serious about working with Trump to normalize the US-DPRK relationship. They made a distinction between the nuclear weapons they possessed and the nuclear facilities that produced them, and included in the joint statement with South Korea’s President Moon their willingness to trade the Yongbyon facilities for unspecified “corresponding measures” taken by the U.S.23 Given that one of the agreements made in Singapore was to build mutual confidence, they are likely to see the dismantling of its nuclear facilities as part of confidence-building measures. They may have thought they were following Charles Osgood’s suggestion of GRIT (Graduated Reciprocation in Tension Reduction): offer a concession first with the expectation that it will be reciprocated by the other party.24

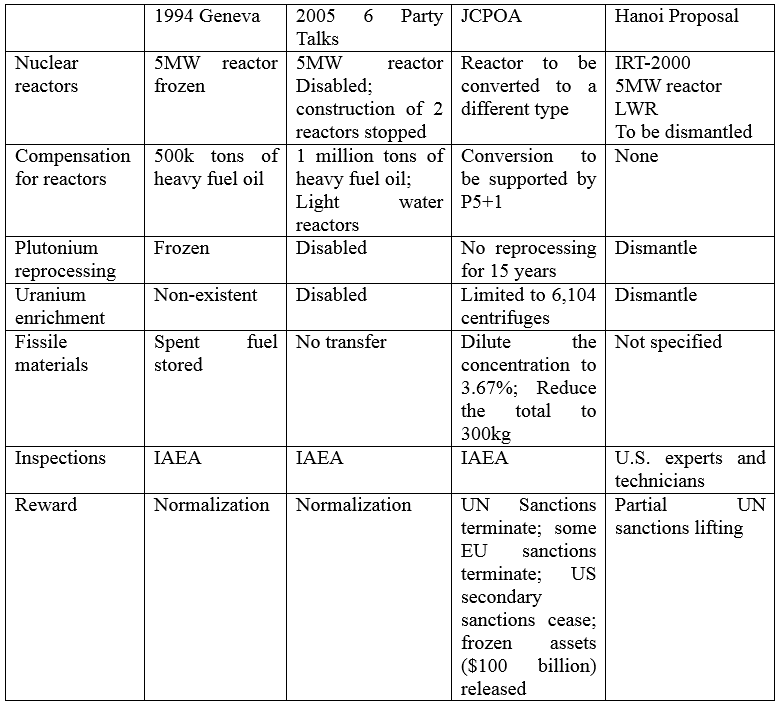

They fattened the concession by proposing in Hanoi that they would “permanently and completely dismantle all the nuclear material production facilities in Yongbyon,” as revealed by Foreign Minister Ri.25 The magnitude of this proposal completely eclipsed the previous deals made by the North or Iran (See Table 2 for a comparison). In the Geneva Agreed Framework or the Six Party Talks, Pyongyang agreed to “freeze” or “disable” their nuclear facilities, and fiercely opposed the use of the word “dismantle” in the September 19 Joint Statement of 2005 that the six parties settled on, choosing “abandon” as the action it would take. This time they proposed to “dismantle.” By proposing to dismantle the entire Yongbyon nuclear facilities, moreover, they indicated their willingness to give up even the civilian use together with the military use, contrary to their previous demands and the Iran nuclear deal (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action) that allowed civilian use of nuclear facilities while limiting military use. In return, they sought to lift five of the UN sanctions that affected civilian economy, a much more modest reward than it previously demanded (lifting the sanctions) and than Iran received in return for its agreement to limit the operation of its nuclear facilities. In short, they turned Kim Jong Un’s earlier offer—included in the Pyongyang Joint Declaration to dismantle the Yongbyon nuclear facilities for U.S. “corresponding measures”—into a detailed proposal that involved giving up more in return for less. What looks like a ‘more for less’ proposal might have been part of their first moves to maximize the likelihood of the Trump team’s reciprocation.

|

Comparison between the North’s Hanoi proposal and other nuclear agreements |

Their first moves, however, far from being reciprocated as they hoped, met with additional U.S. sanctions, raising questions about how much they could work with Trump. That they were slapped at the Hanoi summit with additional demands to close down all WMD programs—not just nuclear weapons facilities—not only added to their distrust but also likely rekindled fears that the US negotiation agenda was to persuade them to disarm as part of the ongoing war. It would not be surprising if they were reminded of the fate of Saddam Hussein and Muammar Qaddafi. They probably remember, at least as well as we do, that the Bush administration had made the same demand of the Hussein government prior to the invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003. While Biegun justifies the demand to dismantle WMD as part of the peace regime in the second clause of the Singapore agreement—and the complete dismantlement of all WMDs and their production capabilities would certainly be part of the end state—such a demand as a precondition for all other measures was received even by South Korea’s observers as tantamount to a demand for surrender that the North would never accept.26 In a recent speech he made after the summit, Kim Jong Un in fact characterized the American proposal as a ploy to achieve “first disarmament and second regime change.”27

The North Korean officials came to Hanoi in order to see if Trump himself was serious about delivering the promises he had made in Singapore in terms of the normalization and peace as well as denuclearization. When they stated after the Hanoi summit that they could not understand the Americans’ logic that they must disarm in order to receive economic benefits, they were probably expressing their frustration that they could not move Trump even with the best proposal they could make.28 Even if North Korean officials delivered pointed criticisms of Bolton and Pompeo after the summit’s failure, their intended audience was likely Trump. And they took pains to exalt Kim’s relationship with him even after Hanoi to reiterate their hope that the maverick might actually terminate the 70 year-old war with the North, although in his SPA speech Kim set a deadline on the hope.29 The April North Korean test of a “tactical guided weapon” and Kim’s first summit with Russia’s Putin suggests that they are not sitting idly until the deadline.

However, I argue they must learn a different lesson from the experience. They must realize that they cannot normalize relations with the United States solely on the basis of negotiation with Trump. It is not just because of his personal characteristics. The US is not a country that boasts of unity between the people and the supreme leader. If they are serious about normalization, they need to engage others in the administration and in the Congress, not just Trump. They must engage scholars, journalists, writers and students. They need to convince the American nation—at least a significant part of it—that they are serious about normalization, the peace process, and denuclearization.

They need to engage Americans, and others, on many issues beyond nuclear weapons and national security. When we say it is not enough to convince Americans that they destroyed their nuclear test site or closed down their rocket facility, we don’t necessarily mean that they need to dismantle all their weapons of mass destruction and production capabilities. We mean that they need to engage Americans on economy, environment, health, education, arts, music, etc. so that we may understand them better and normalize our views of them. They need to discuss with Americans the unending Korean War and its cost to the Koreans and the Americans and others; and both nations must be engaged in a collective search for a better alternative. That will help the administration forge ahead with diplomacy. That will help Congress support its diplomacy. That will help the public to support it. And of course, the US must reciprocate. It needs to engage the North on multiple fronts with a view to normalizing the relationship. It will take a lot of work. It will take time. But there really is no alternative to a comprehensive approach.

South Korea can allay North Korean security concerns

So we have a dilemma. On the one hand, we need a comprehensive approach that will address many issues of concern concurrently. On the other hand, such a comprehensive approach won’t be implemented by the Trump Team or the Kim Team. So what to do?

Philip Zelikow makes an important point that I believe is a key to solving the dilemma: “The two Koreans should be at the center.”30 And I think South Korea has central roles to play in helping build confidence between Washington and Pyongyang, which will in turn help to achieve a comprehensive agreement adopted and implemented by both.

The two Koreas have since 1990 made a number of important agreements that lay out their “special relationship on the way to unification,” although they have yet to implement them to the full. The last two agreements, made by Moon and Kim at Panmunjom and Pyongyang in 2018 address the most challenging issues: national security. They agreed to demilitarize the DMZ—which is arguably the world’s most militarized zone contrary to the name—and take several measures to diminish the likelihood of a conflict. The Moon and the Kim governments have made progress toward implementing these agreements that some analysts characterize as a de facto peace agreement or non-aggression pact between the Koreas.

In light of, and in line with, the progress between the Koreas, South Korea can play three indispensable roles. First, the Moon government could implement the agreements with Pyongyang. One important aspect of these agreements is that the two leaders agreed to “remove the danger of war from the entire Korean peninsula” and “fundamentally resolve the enmity.”31 If the agreed goal is achieved, that would establish a de facto peace regime between the two Koreas. The inter-Korean peace-regime could facilitate the process of normalizing the North’s relationship not only with the U.S. but also with Japan, and could be part of a larger process to build peace in Northeast Asia. This would help allay Pyongyang’s security concerns. It could also encourage the Kim Team to turn to a multi-track approach with reduced obsession on the security track.

The second important realm of inter-Korean agreement would involve increased exchanges and cooperation between the two Koreas on a multiplicity of issues, including humanitarian, environmental, public health, and economic ones. As this aspect of the agreements is realized, it will open up more channels of communication and raise the level of transparency, which will in turn allay (or confirm) Washington’s suspicion—and South Koreans’ concerns—about the Kim Team’s intentions. As the increase in communication and transparency allays Washington’s concerns, it could help the Trump Team relax its preconditions for the North’s disarmament and turn to the multi-track approach that includes disarmament as part of the end state.

As the two Koreas make progress on implementing their agreements, they can take further steps toward regularizing and institutionalizing several levels of official meetings, from the inter-Korean summit to the prime ministerial level to a ministerial level and to working level meetings, just as Germany and France did after World War II. South Korea’s Parliament may hold a joint meeting with North Korea’s Supreme People’s Assembly. There could, of course, be meetings and exchanges outside the government framework. Progress on institutionalizing the inter-Korean relationship helps consolidate the peace regime and is thus “essential to full denuclearization of the peninsula,” as Paik notes.32 Many of these meetings and exchanges can be held without requiring relaxation of existing sanctions. As progress is made, some sanctions may of course be relaxed or lifted.

Finally, given that the Hanoi summit failed due to the incompatibility of the Trump and the Kim approaches, as I argue in the first section, public diplomacy between the two countries, and indeed between the two nations, would go a long way toward building trust, which will ultimately facilitate denuclearization and the peace process on the Korean peninsula. Thus the Moon government could perhaps persuade the Trump and the Kim administrations to consider going further than existing agreements. Why not, for example, send Lady Gaga, Ariana Grande and Kendrick Lamar to North Korea for a national tour? Why not ask BTS and Black Pink to do the same? In return, why not invite North Korea’s idol girl group, the Samjiyon group, or the North’s national orchestra, for a national tour of the US, Japan and South Korea? Women’s soccer matches should also be considered. The 2020 Summer Olympics presents an exceptional opportunity for the Koreans to meet and practice together as a unified team and for the Koreas to show a unified face to the world. Also it gives Tokyo an excuse to offer an olive branch to Pyongyang to engage in a dialogue on not only sports but also other issues.

If Trump and Kim meet again amidst such developments, they could find it easier to hammer out an agreement. The Trump team might discover merits in Kim’s Hanoi proposal that he previously failed to notice. He might also notice an important gap in the proposal: its failure to specify what will be done about the fissile material possessed by the North. He may call upon Kim to make a more comprehensive proposal that addresses the gap. Kim may of course make his own proposal specifying what he seeks in return for giving up fissile material.

Furthermore, the interlude after Hanoi is providing both of them with time to imagine how they might anchor their respective vision in the wider region. When Biegun made a path- breaking speech in January 2019 that laid out a vision of a new relationship with the DPRK, he carefully built the vision on the basis of a new orientation that acknowledged differences between the two countries not just as differences, neither identifying them as evidence for the North’s deviance nor criticizing the country for the deviance.33 His cognitive framework took a revolutionary departure from the traditional one that identified the North as the evil as in the “axis of evil,” as he might have attempted to bring North Korea from the “sphere of deviance” to the ‘sphere of legitimate controversy.”34 Yet he was standing on a thin reed. Not only was his a lone voice inside the beltway. Also he built his Korea vision on this air because he stopped short of thinking through what such a radical reorientation might entail for Northeast Asia. Likewise, while Pyongyang’s Hanoi proposal was bold—bolder than ever—it was so singularly obsessed with testing Trump’s trustworthiness that its details were presented in the void of the regional context. It is almost as if Pyongyang and Washington were trying to establish a new US-DPRK relationship, a peace regime and denuclearization of the Korean peninsula in a vacuum. The Hanoi breakdown is giving both Washington and Pyongyang a necessary break to imagine how to anchor their peninsula vision to the region’s future. South Korea can perhaps work with them on this also, and can possibly contribute more as it is in a better position than either to engage the other regional actors, China, Russia, and Japan, in a collective search for an alternative regional order.35

All in all, a further development of the inter-Korean relationship, combined with public diplomacy, would go a long way toward building mutual understanding between the North and the US. The strengthening of the inter-Korean relationship and the consolidation of the peace regime will provide Pyongyang—and Seoul—with an institutional foundation that allays security concerns, which will help the Kim team move toward denuclearization. The more secure the peace regime is, the less insecure the North will be. Also the more institutionalized inter-Korean exchanges become, the more information about North Korea would become available. As these factors increase the transparency of Pyongyang’s intentions and goals, it could reduce Washington’s concerns about Pyongyang’s credibility. Public diplomacy, combined with these measures, will help both Pyongyang and Washington take steps toward adopting and implementing a comprehensive agreement that is difficult but is the only real solution to the multiplicity of issues between the countries and in the region.

Joint Statement of President Donald J. Trump of the United States of America and Chairman Kim Jong Un of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea at the Singapore Summit

President Donald J. Trump of the United States of America and Chairman Kim Jong Un of the State Affairs Commission of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) held a first, historic summit in Singapore on June 12, 2018.

President Trump and Chairman Kim Jong Un conducted a comprehensive, in-depth, and sincere exchange of opinions on the issues related to the establishment of new U.S.–DPRK relations and the building of a lasting and robust peace regime on the Korean Peninsula. President Trump committed to provide security guarantees to the DPRK, and Chairman Kim Jong Un reaffirmed his firm and unwavering commitment to complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

Convinced that the establishment of new U.S.–DPRK relations will contribute to the peace and prosperity of the Korean Peninsula and of the world, and recognizing that mutual confidence building can promote the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, President Trump and Chairman Kim Jong Un state the following:

- The United States and the DPRK commit to establish new U.S.–DPRK relations in accordance with the desire of the peoples of the two countries for peace and prosperity.

- The United States and the DPRK will join their efforts to build a lasting and stable peace regime on the Korean Peninsula.

- Reaffirming the April 27, 2018 Panmunjom Declaration, the DPRK commits to work toward complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

- The United States and the DPRK commit to recovering POW/MIA remains, including the immediate repatriation of those already identified.

Having acknowledged that the U.S.–DPRK summit—the first in history—was an epochal event of great significance in overcoming decades of tensions and hostilities between the two countries and for the opening up of a new future, President Trump and Chairman Kim Jong Un commit to implement the stipulations in this joint statement fully and expeditiously. The United States and the DPRK commit to hold follow-on negotiations, led by the U.S. Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, and a relevant high-level DPRK official, at the earliest possible date, to implement the outcomes of the U.S.–DPRK summit.

President Donald J. Trump of the United States of America and Chairman Kim Jong Un of the State Affairs Commission of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea have committed to cooperate for the development of new U.S.–DPRK relations and for the promotion of peace, prosperity, and security of the Korean Peninsula and of the world.

DONALD J. TRUMP

President of the United States of America

KIM JONG UN

Chairman of the State Affairs Commission of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

June 12, 2018

Sentosa Island

Singapore

(Source: The White House.)

Pyongyang Joint Declaration of September 19, 2018

Moon Jae-in, President of the Republic of Korea and Kim Jong-un, Chairman of the State Affairs Commission of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea held the Inter-Korean Summit Meeting in Pyongyang on September 18-20, 2018.

The two leaders assessed the excellent progress made since the adoption of the historic Panmunjeom Declaration, such as the close dialogue and communication between the authorities of the two sides, civilian exchanges and cooperation in many areas, and epochal measures to defuse military tension.

The two leaders reaffirmed the principle of independence and self-determination of the Korean nation, and agreed to consistently and continuously develop inter-Korean relations for national reconciliation and cooperation, and firm peace and co-prosperity, and to make efforts to realize through policy measures the aspiration and hope of all Koreans that the current developments in inter-Korean relations will lead to reunification.

The two leaders held frank and in-depth discussions on various issues and practical steps to advance inter-Korean relations to a new and higher dimension by thoroughly implementing the Panmunjeom Declaration, shared the view that the Pyongyang Summit will be an important historic milestone, and declared as follows.

- The two sides agreed to expand the cessation of military hostility in regions of confrontation such as the DMZ into the substantial removal of the danger of war across the entire Korean Peninsula and a fundamental resolution of the hostile relations.

- The two sides agreed to adopt the “Agreement on the Implementation of the Historic Panmunjeom Declaration in the Military Domain” as an annex to the Pyongyang Declaration, and to thoroughly abide by and faithfully implement it, and to actively take practical measures to transform the Korean Peninsula into a land of permanent peace.

- The two sides agreed to engage in constant communication and close consultations to review the implementation of the Agreement and prevent accidental military clashes by promptly activating the Inter-Korean Joint Military Committee.

- The two sides agreed to pursue substantial measures to further advance exchanges and cooperation based on the spirit of mutual benefit and shared prosperity, and to develop the nation’s economy in a balanced manner.

- The two sides agreed to hold a ground-breaking ceremony within this year for the east-coast and west-coast rail and road connections.

- The two sides agreed, as conditions ripe, to first normalize the Gaeseong industrial complex and the Mt. Geumgang Tourism Project, and to discuss the issue of forming a west coast joint special economic zone and an east coast joint special tourism zone.

- The two sides agreed to actively promote south-north environment cooperation so as to protect and restore the natural ecology, and as a first step to endeavor to achieve substantial results in the currently on-going forestry cooperation.

- The two sides agreed to strengthen cooperation in the areas of prevention of epidemics, public health and medical care, including emergency measures to prevent the entry and spread of contagious diseases.

- The two sides agreed to strengthen humanitarian cooperation to fundamentally resolve the issue of separated families.

- The two sides agreed to open a permanent facility for family reunion meetings in the Mt. Geumgang area at an early date, and to promptly restore the facility toward this end.

- The two sides agreed to resolve the issue of video meetings and exchange of video messages among the separated families as a matter of priority through the inter-Korean Red Cross talks.

- The two sides agreed to actively promote exchanges and cooperation in various fields so as to enhance the atmosphere of reconciliation and unity and to demonstrate the spirit of the Korean nation both internally and externally.

- The two sides agreed to further promote cultural and artistic exchanges, and to first conduct a performance of the Pyongyang Art Troupe in Seoul in October this year.

- The two sides agreed to actively participate together in the 2020 Summer Olympic Games and other international games, and to cooperate in bidding for the joint hosting of the 2032 Summer Olympic Games.

- The two sides agreed to hold meaningful events to celebrate the 11th anniversary of the October 4 Declaration, to jointly commemorate the 100th anniversary of the March First Independence Movement Day, and to hold working-level consultations toward this end.

- The two sides shared the view that the Korean Peninsula must be turned into a land of peace free from nuclear weapons and nuclear threats, and that substantial progress toward this end must be made in a prompt manner.

- First, the North will permanently dismantle the Dongchang-ri missile engine test site and launch platform under the observation of experts from relevant countries.

- The North expressed its willingness to continue to take additional measures, such as the permanent dismantlement of the nuclear facilities in Yeongbyeon, as the United States takes corresponding measures in accordance with the spirit of the June 12 US-DPRK Joint Statement.

- The two sides agreed to cooperate closely in the process of pursuing complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

- Chairman Kim Jong-un agreed to visit Seoul at an early date at the invitation of President Moon Jae-in.

September 19, 2018

(Source: The Korea Times)

Notes

This is an expanded and updated version of the keynote speech delivered at the symposium “To End the Korean War? Peace on the Peninsula” University of Virginia, March 20, 2019. Available here. Some parts are drawn from my op-eds in Hankyoreh and OhMyNews. I thank the symposium organizers, especially Seunghun Lee, and participants as well as Mark Selden and Gavan McCormack for their helpful feedback.

Reuters reported that in Hanoi President Trump handed Kim a document that detailed what the Americans defined as denuclearization. It reportedly included four additional demands: “to provide a comprehensive declaration of its nuclear program and full access to U.S. and international inspectors; to halt all related activities and construction of any new facilities; to eliminate all nuclear infrastructure; and to transition all nuclear program scientists and technicians to commercial activities.” Lesley Wroughton, David Brunnstrom, “Exclusive: With a piece of paper, Trump called on Kim to hand over nuclear weapons,” Reuters, March 30, 2019.

Stephen Biegun and Helene Cooper, “A Conversation with U.S. Special Representative Stephen Biegun,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 11, 2019.

Biegun lists two additional actions taken by Pyongyang: the return of the remains of U.S. soldiers and a U.S. citizen. Ibid.

One new sanction was announced in each of the months of January and February, and the Treasury Department reissued the existing North Korea sanctions regulations on March 1st 2018. U.S. Department of Treasury, “2018 OFAC Recent Actions.” Available here.

Ri Yong Ho, DPRK’s Foreign Minister, revealed after the Hanoi summit that the North Koreans asked the Trump team to lift the five UN sanctions that affected civilian sectors

Gregg Re, “Bolton claims Trump doesn’t necessarily believe Kim on Warmbier, says third summit possible,” Fox News, March 3, 2019.

Dexter Filkins, “John Bolton on the Warpath: Can Trump’s national-security adviser sell the isolationist President on military force?” The New Yorker, April 29, 2019

According to CNN, Trump “described Kim as singularly focused on ending the sanctions that have crippled his economy and helped bring him to the negotiating table in the first place.”

Kevin Liptak and Jeremy Diamond, “‘Sometimes you have to walk’: Trump leaves Hanoi with no deal,” CNN, February 28, 2019.

According to the SPA reports for the past several years, the national income has continuously grown faster than the trade performance, presumably because a growth in the domestic economy can more than compensate for a slower trade growth. In contrast, Iran is so heavily dependent for the economy on oil exports that international sanctions took a serious toll.

This is an old slogan, first used by the Japanese in the early 1930s and the Chinese later, that prizes building an independent, not necessarily autarkic, economy with one’s own efforts and without relying on outside assistance. Kim Jong Un brought it up in his 2017 new year’s address, after having used a slightly different formulation, “자강력 (自強力)” in the 2016 new year’s address. The Rodong sinmun ran a major editorial on December 12, 2018, and the campaign seems to be picking up fervor the following year.

Jae-Jung Suh, “Kim Jong Un’s Move from Nuclearization to Denuclearization? Changes and Continuities in North Korea and the Future of Northeast Asia,” The Asia Pacific Journal, Vol. 16, Issue 10, No. 2 (May 15, 2018).

Jae-Jung Suh, “Half Full or Half Empty? North Korea after the 7th Party Congress,” The Asia Pacific Journal, Vol. 14, Issue 14, No. 9 (July 15, 2016).

Jae-Jung Suh, “The Imbalance of Power, the Balance of Asymmetric Terror: Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) in Korea” in Imbalance of Power: Transforming U.S.-Korean Relations, edited by John Feffer (New York: Routledge, 2006), pp. 64-80.

North Koreans have clearly indicated what they mean by the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula. In a National Defense Commission’s statement of June 15, 2013, for example, its spokesperson explains its understanding as “the denuclearization of the entire Korean peninsula, including South Korea, and the most thorough denuclearization that aims to completely terminate nuclear threats from the U.S.”

Kim, International Secretary of the Korean Workers Party, met Arnold Kanter, U.S. Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, on January 21 1992 to explore the possibility. Such explorations resulted in the Geneva Agreed Framework of 1994 that included the normalization of the relationship as one of the objectives. 백학순, “북미정상회담: 배경, 이슈, 전망,” 정세와 정책, 265호 (2018년 4월).

Kim Dae-Jung, Conscience in Action: The Autobiography of Kim Dae-Jung, translated by Jeon Seung-hee, (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 645-6.

Article 2 of Joint Statement of the Six Party Talks, issued on September 19, 2005, commits Pyongyang and Washington to respect each other’s sovereignty, peacefully coexist, and normalize their relationship. Article II of February 13th Agreement of 2017 commits Pyongyang and Washington to start a bilateral talk to open a diplomatic relationship.

Kim Il Sung, Kim Jong Il and South Korea’s President Kim Dae-Jung apparently shared such a view. Kim Jong Il told Kim Dae-Jung during their summit in 2000 that he agreed that U.S. forces should remain in Korea even after reunification in order to maintain a balance of power. Ibid.

The central government budget, which correlates with the national economy, has continuously grown at 4.6~6.3% annually since 2014. While the North’s exports to China fell by 87% and its imports by 33% from 2017 largely due to UN sanctions, its trade volume in 2018 was still larger than in 2009 or 2010. Despite the trade decrease, the domestic market remained stable—unlike Iran that saw a tripling of market prices from 2010 to 2015. The market price of rice, for example, remained stable at a lower level in 2018 than the previous year. The central government budgets were drawn from Rodong sinmun, various years. Trade and rice prices are from Lee Suk, “총괄: 2018년 북한경제, 위기인가 버티기인가?” KDI북한경제리뷰 (2019년 2월), pp 3-28.

Andrew Bacevich, Washington Rules: America’s Path to Permanent War (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2010).

Kim Jong Un pledged in the summit meeting with Moon on September 19, 2018 that the Yongbyon nuclear facilities would be permanently dismantled if the U.S. took “corresponding measures.” Pyongyang Joint Declaration of September 2018.

Osgood, Charles Egerton. Graduated Reciprocation in Tension-Reduction, a Key to Initiative in Foreign Policy. Urbana: Institute of Communications Research University of Illinois, 1960.

Foreign Minister Ri stated after the summit that “it might be difficult for an opportunity like this to come again.” First Vice Foreign Minister Choe Son Hui also described the opportunity as “천재일우 (千載一遇) [once in a thousand years,” indicating a better deal would be highly unlikely. “[전문] 北리용호·최선희 심야 기자회견 발언(종합),” 매일경제, 2019.03.01.

Phillip Zelikow, Keynote Address at the symposium “To End the Korean War? Peace on the Peninsula” University of Virginia, March 20, 2019. Available here.

Moon Jae-in and Kim Jon Un, Pyongyang Joint Declaration, September 19, 2018. In their Panmunjeom Declarationi for Peace, Prosperity, and Unification of the Korean Peninsula, April 27, 2018, they agreed to “make joint efforts to alleviate the acute military tension and practically eliminate the danger of war on the Korean Peninsula.”

Nak-chung Paik, “South Korea’s Candlelight Revolution and the Future of the Korean Peninsula,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 16, Issue 23, No. 3 (December 1, 2018).

It might have been a poisoned carrot in the sense that in this speech, he openly introduced the demand on WMDs. Nevertheless, his speech is noteworthy for its cognitive framework radically different from the traditional one. Stephen Biegun, “Remarks on DPRK at Stanford University,” Palo Alto, CA, United States, January 31, 2019.

The concepts of the sphere of deviance and the sphere of legitimate controversy were developed by Hallin to explain the U.S. media’s coverage of the Vietnam War, but equally applicable to American discourses about North Korea. Hallin, Daniel C. The “Uncensored War”: The Media and Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Marilyn Young notes that the movement to end the Vietnam War accomplished much more than generating pressure on the U.S. government. It “opened up for debate not only the principles that governed American foreign policy since the end of World War II, but the larger structure of the nation and its political procedures.” The efforts to end the Korean War can perhaps draw inspiration from that experience. Young, Marilyn Blatt. The Vietnam Wars, 1945-1990. 1st ed. New York: HarperCollins, 1991, p. 203.